Appendix 6

Assembly Research

Research and Library Services

_fmt1.jpeg)

24 November 2008

Public Procurement and SMEs

Dr Robert Barry

This briefing paper provides a general overview of SME performance in securing public procurement contracts. It also looks at some of the barriers encountered by SMEs in relation to the public procurement process, including the particular problems faced by the social economy sector.

Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of The Assembly and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public.

Public Procurement and SMEs

Introduction

Public procurement covers a wide range of supplies, services and works required by governments, local authorities and public organisations, utilities and agencies. The size of such contracts varies hugely. Whilst some are beyond the capabilities of SMEs[1] to fulfil, a significant proportion of the public procurement opportunities in Europe are well within the scope of SMEs. With a market in the EU estimated at around 16% of GDP, or about €1,800 billion in 2006, public procurement contracts represent a major opportunity for very many enterprises.[2]

The public sector in Northern Ireland spends approximately £1.7bn out of a total budget of £7bn each year on public procurement. While it is impossible to detail the full range of works, goods and services that these public bodies purchase, the most common procurement are: Accountancy/Audit; Banking; Bottled Water; Catering Equipment; Catering Services; Cleaning Services; Clothing and Footwear; Construction/ Maintenance Services; Facilities Management; Food Products and Beverages; Furniture and Fittings; ICT Equipment; Information and Computer Technology Services; Laundry Services; Legal Services; Medical and Laboratory Devices; Medical Surgical Equipment and Supplies; Office Machinery; Pharmaceuticals; Plant and Machinery; Post Office Counters; Protective Wear; Repair, Maintenance and Installation Services; Tools, Equipment and Building Materials; Training Services; and Uniforms.[3]

The Experiences of SMEs in Public Procurement

SMEs’ access to public procurement varies from one Member States to another. In 2005, SMEs secured 42% of the value and 64% of the number of contracts above the thresholds fixed by the EU directives on public procurement.[4] The directives cover roughly 16% of the EU public procurement market. SMEs tend to perform better in bidding for central government contracts and less well in the old Member States compared with the new. It is also interesting to note that medium sized companies perform much better than small and micro companies.[5]

In 2004, the EU Council and Parliament adopted a package of directives on public procurement designed to reduce the administrative burden and costs related to tendering, make procurement systems more transparent and easier for SMEs (in particular) to access, and encourage the use of information technology systems (e-procurement) to simplify the process. These directives were due to be transposed into national law in all Member States by January 2006.

To facilitate this ongoing process, within the framework of the European Small Business Act (introduced by the Commission on 25 June 2008)[6] the European Commission proposed a Code of Best Practices to assist SMEs in the public procurement process. The Code encourages Member States to learn from each other as they implement the new rules under the public procurement directives. The Small Business Act also includes 10 principles to guide the conception and implementation of policies at EU and Member State level. These policies include granting a second chance for business failure, facilitating access to finance and enabling SMEs to turn environmental challenges into opportunities.[7]

Despite actions taken at both EU and national level, there are still many barriers which discourage SMEs from responding to these EU-wide tenders. These include basic difficulties in finding information about tenders, or about the procedures for bidding, or there are problems in understanding jargon; too short a deadline for responding and/or the costs of responding are too high; the administrative procedures are too complex, or particular certification is required; a high financial guarantee is required to bid; or companies may face discrimination on the basis that they are located in a different country from the contracting authority.[8]

A recent report on the experience of European SMEs, entitled “Evaluation of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’ (SMEs’) Access to Public Procurement Markets", highlighted the problems faced by SMEs. The study was undertaken by GHK and Technopolis between April and September 2007 on behalf of Directorate-General Enterprise and Industry.[9]

The study found that the most frequent problem faced by European SMEs in bidding for public procurement tenders is the over-emphasis placed on price by awarding authorities (52% of the companies encountered this either ‘regularly’ or ‘often’). Onerous paperwork requirements were also mentioned as a common problem (46%).

The use of e-mails as a preferred channel of communication, improving tender specifications and documentation, as well as improving information on tenders in general were seen as the three most helpful actions that awarding authorities could do. Training for companies, the use of framework agreements and contracts, and more time to draw up tenders were less frequently emphasised.

Overall the study findings suggest that there is still scope for improvement in the performance of SMEs in public procurement. The report therefore recommended that steps should be taken to: reduce differentials in access between SMEs, and in particular small and micro-enterprises, and larger companies; exchange experience and encourage peer learning activity amongst Member States and awarding authorities; and, improve the information and research base.

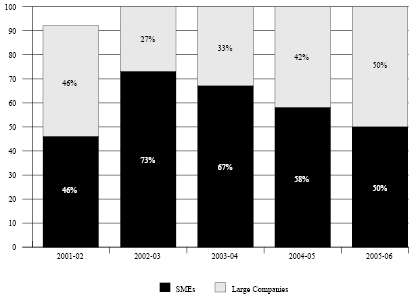

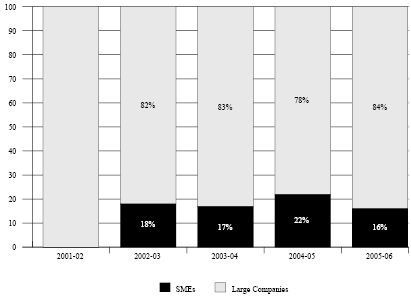

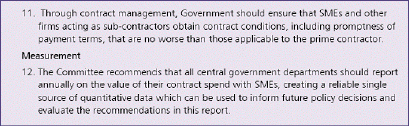

Within the UK, there has been a decline in recent years in the number of contracts being awarded to SMEs following an initial leap in 2002/03 in reaction to the work carried out by the Office of Government Commerce (OGC) and government reviews (Figure 1). Whilst the number of contracts awarded to SMEs has been relatively high, the total value has consistently remained around the 20% mark (Figure 2).[10]

Figure 1. Share of number of UK public sector contracts awarded by company size

Table 2. Share of value of UK public sector contracts awarded by company size

In 2003, the Better Regulation Task Force (BRTF), in collaboration with the Small Business Council (SBC), set out with the aim to “counter the excessive burdens on small businesses". Their report “Government: Supporter or Customer?" was produced in reaction to the fact that whilst SMEs are very important to the UK economy (99% of all businesses) they are underrepresented in public procurement contracts. The report aimed to consider the barriers that face SMEs when doing business with the public sector and the wider benefits to the economy when procuring from SMEs. Eleven recommendations were put forward in the report to be carried out by procurement offices both at the national and local government levels.[11]

Recommendation 1

- The DTI should ensure adequate resources for the “Supplying Government" web portal project. The portal should advertise lower value contracts from across central government and include information on future contract opportunities. There should be a named contact for each advertised contract. The portal should be set up and piloted by spring 2005.

Recommendation 2

- The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Local Government Association should encourage local authorities to develop “selling to the council" websites by 2005. Websites should include information on contracts for tender, forthcoming contract opportunities and guidance on how to do business with the council. There should be a named contact for each advertised contract.

Recommendation 3

- Within the context of small business support, the Small Business Service should provide advice and training for small and medium-sized enterprises on how to do business with central government and local councils. The Business Links Operators should deliver this by spring 2004.

Recommendation 4

- Regional Development Agencies should ensure by spring 2004 that, as part of the supply chain development work for which they are already funded, they work with prime public sector contractors to develop opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Recommendation 5

- The public sector should develop a common core pre-qualification information document for lower value contracts so that businesses do not have to put together different information in different formats to get past the expression of interest stage. The Office of Government Commerce and the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister working with the Local Government Association should develop and pilot this by spring 2004.

Recommendation 6

- The Small Business Service should publicise the mechanism for reporting non-compliance with the Office of Government Commerce “Government Procurement Code of Good Practice" that firms can use to ensure that they receive adequate debriefing.

Recommendation 7

- The Office of Government Commerce, the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister with the Local Government Association should consider how to promote the wider use of the Government Procurement Card, recently extended by the Office of Government Commerce, to include local authorities and other non central civil Government bodies, in order to improve prompt payment by the end of 2003.

Recommendation 8

- The Office of Fair Trading should carry out research to identify the characteristics of those markets where it is important to ensure that small and medium-sized enterprises are able to compete to ensure competition, particularly where this may have an impact on innovation and value for money achieved by public sector procurement. Within this, it should also assess the impact of framework agreements and contract aggregation on small and medium-sized enterprises.

Recommendation 9

- Where public sector procurers opt for prime contractors, they should ensure that their business case for doing so in those particular markets brings value for money. Public sector procurers should ask prime contractors during the procurement process to demonstrate their track record in achieving value for money through effective use of their supply chain – including use of small and medium-sized enterprises. This should also be examined as part of the on-going contract management. Public sector procurers should ensure that prime contractors pay subcontractors on time and that when paying progress payments to prime contractors the payments flow down through the supply chain. In order to make subcontracting opportunities more transparent to small and medium-sized enterprises, Government Departments and local authorities should list details of prime contractors and contracts on their websites.

Recommendation 10

- The Local Government Procurement Forum, with input from the Small Business Service, should develop an SME-friendly procurement concordat. All local authorities should be able to sign up to this by 2005.

Recommendation 11

- The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Local Government Association should encourage local authorities to set out in their procurement strategies the steps they are taking to engage with small and medium-sized enterprises by the end of 2003. Government Departments should include in their procurement policy statements the steps they take to engage with small and medium-sized enterprises by the end of 2003 or publish this information in their annual reports.

Most of these recommendations have now been acted upon by local and national bodies. Guidance has also been published by the OGC and by the respective regional procurement bodies with the aim of overcoming the barriers faced by SMEs and to help realise the benefits of involving them in public procurement contracts.

Recent research, however, by a company called Freshminds, suggests that more still needs to be done to address the problems faced by SMEs in relation to public procurement. Their findings included the following:[12]

- Nearly three quarters of SMEs rarely or never bid for government work.

- Over three quarters of SMEs believe that there are barriers to awareness of government opportunities.

- Over half of SMEs feel that the process of tendering for government contracts requires more time and resource than their business can allow.

- On average, SMEs find the private sector easier to sell to than the public sector – their rate of success in winning private sector contracts is double their rate of success in winning public sector contracts.

- Nearly three quarters of SMEs feel that the public sector is more difficult to deliver work to than the private sector, due to a greater amount of formality, a lack of responsiveness and unrealistic timescales.

In addition to recommending a number of practical steps for SMEs to take (in terms of identifying opportunities, preparing for bids, and meeting customer needs), the researchers recommended a number of ways in which Government could continue to work to improve the procurement process for SMEs:

- Improve SME access to information on public procurement opportunities - Whilst considerable progress has been made, it is imperative to develop one single point of reference for SMEs to find information about bidding opportunities available to them.

- Simplify and clarify the bidding process - Existing portals are known to confuse some applicants. The Government needs to move towards simplifying the procurement process from start to finish, both in terms of the administrative burden and the use of accessible language.

- Reduce bureaucracy (compliance demands) - Efforts to reduce the bureaucracy for SMEs should impact both the time spent to amalgamate information required in bids as well as the level of contractual compliance required by procurers, which is often prohibitive for small companies.

- Make the process more transparent - Some SMEs still perceive some procurement bias, particularly towards lower cost options. Procurement needs to continue to become more transparent, selecting on the basis of value for money.

- Provide appropriate support schemes for SMEs - Guidance documents and ‘Meet the Buyer’ events can be extremely valuable for SMEs in improving their chances of winning a contract.

- Introduce innovative measures such as performance bonds and contract banding to combat the perceived risk associated with SMEs - Any reduction of the risks associated with contracting with SMEs would likely result in an increase in procurement from these companies.

- Provide constructive and clear feedback on lost bids - Some public sector organisations are still not providing timely and appropriate feedback to SMEs, which makes improving their future chances of winning bids more difficult.

- Support the expertise of public sector procurement professionals - The greater the skills and experience that procurement professionals can apply to their job, the more likely the process is to be transparent and appropriate.

- Make delivery terms and conditions more adaptive to the needs of the SME supplier - SMEs are often less able to cope with prolonged periods of financial insecurity; simply paying invoices in a timely manner and speeding up the contractual process would benefit smaller companies.

The Social Economy Sector

The social economy includes co-operatives, mutual societies, non-profit associations, foundations and social enterprises. From the village farmers who set up a co-operative to market their produce more effectively to the group of savers who set up a mutual to ensure they each receive a decent pension, by way of charities and organisations offering services of general interest, the social economy touches a huge range of individuals across Europe. There are around 10 million jobs in the social economy across Europe, but membership of social economy enterprises is much wider, with estimates ranging as high as 150 million.[13]

Different Member States have different traditions, so the forms of enterprise and the fields in which they are active vary across Europe, but there are few areas where the social economy has no interest. Co-operatives are prominent in fields such as banking, craft industries, agricultural production and retail. Mutual societies are found in the insurance and mortgage sectors, whilst associations and foundations are active in health and welfare services, sports and recreation, culture, environmental regeneration, humanitarian rights, development aid, consumer rights, education, training and research.

Whilst some social economy enterprises provide services on behalf of or instead of the public sector, for example healthcare and social services, others produce products or services sold on the open market in competition with investor-driven companies. In such circumstances, the social economy is an important player in ensuring effective competition and it is therefore vital that regulation takes full account of the specific characteristics of such enterprises.

The social economy sector is big business in the U.K. with at least 15,000 social enterprises contributing some £18 billion to the economy. While Northern Ireland has some baseline data for nearly 400 SEEs with a turnover of just over £355 million (DETI Survey 2007), information on the actual size of the sector is limited.[14]

The social economy sector in Northern Ireland includes a range of organisations such as credit unions, housing associations, local enterprise agencies, community businesses, co-operatives, employee-owned businesses, community development finance initiatives, social entrepreneurs and social firms. Given its relatively low visibility to date and diversity, no firm figures are available to quantify the overall size and scale of the sector. A rough estimate of employment was carried out in June 2000 which indicated a range of between 30,000 and 48,000 jobs (5 - 8% of total employment). However, this was based on different definitions. It is now recognised that this is a relatively limited way of measuring the sector and work is now underway to develop a robust set of baseline figures for the size and scale of the sector as a way of benchmarking against the social economy in the UK and in other regions and to measure growth.[15]

According to the Social Economy Network (SEN), the sector is not as well developed in Northern Ireland as in England and Scotland.[16] They believe that one of the most significant problems facing the development of Social Economy Enterprises (SEEs) in Northern Ireland is the lack of progress on the inclusion of social clauses into the procurement process.

SEN also argue that there is evidence that social enterprises, particularly smaller ones, are at a disadvantage compared with private sector businesses in this arena. There is a limited knowledge of the social economy sector and its potential as a provider of goods and services among public sector procurement personnel. A programme of awareness raising and training is required to ensure that social economy enterprises are equally considered with the private sector in procurement considerations.

Social enterprises with little or no experience of doing business with the public sector also need practical advice and training on procurement procedures and writing tenders so that they can acquire the necessary skills to enable them to take advantage of the opportunities presented.

SEN welcomes the actions proposed by the Central Procurement Directorate to provide information and advice sessions on the tendering process and to organise “Meet the Buyer" events to increase opportunities for SEEs to do business with the public sector.

However, it is their view that SEEs operate their businesses in a market place which does not recognise or take account of the added value they create and this puts them at a disadvantage when competing for public sector business.

The social economy sector is further disadvantaged by the emphasis in consideration of tenders, on financial capacity demonstrated by a build up of reserves in assessing the financial health of companies. This particularly affects those companies in the early stages of development who were prohibited from building up reserves while in receipt of grants. SEN argues that if there is to be equality of opportunity in accessing tenders then it must be acknowledged that existing means and criteria are exclusionary to SEEs and that amendments to criteria must be introduced to create a level playing field.

Some additional problems faced by SEEs who have successfully secured tenders for the delivery of services include the length of time the process takes; and the fact that the level of finance available for service delivery this year, in the health and social care field, is set at 3% less than the cost of delivering the same service last year. Departmental efficiency savings were not intended to affect front line services but it appears that in such instances they will. It is also argued that pressure on public bodies to secure efficiencies by aggregating contracts will discriminate against small businesses, including many social enterprises.

The Social Economy Network (SEN), in its recent presentation to the Enterprise, Trade and Investment Committee, proposed the following actions to help SEEs:

- Inclusion of social clauses into public procurement specifications to ensure a more equal playing field;

- Adoption of a consistent approach to the measurement of social value which can be embedded in the practice and processes of public procurement; and

- Exploration of innovative ways of increasing business opportunities for SEEs through public/social partnerships and private/social partnerships.[17]

[1] Companies classified as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are defined officially by the EU as those with fewer than 250 employees and which are independent from larger companies. Furthermore, their annual turnover may not exceed €50 million, or their annual balance sheet total exceed €43 million. This definition is critical in establishing which companies may benefit from EU programmes aimed at SMEs, and from certain policies such as SME-specific competition rules.

[2] “Opening public procurement to SMEs", European Commission Enterprise and Industry DG - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/public_procurement.htm

[3] “Public Procurement – a guide for social economy enterprises", Central Procurement Directorate, Department of Finance & Personnel - http://www.cpdni.gov.uk/social-economy-enterprises-guidance-pdf.pdf

[4] See OGC website for information on latest EU procurement thresholds - http://www.ogc.gov.uk/procurement_policy_and_application_of_eu_rules_eu_procurement_thresholds_.asp

[5] “Opening public procurement to SMEs", European Commission Enterprise and Industry DG - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/public_procurement.htm

[6] See http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/sba_en.htm

[7] See European Commission Press Release IP/08/1003 -http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/08/1003&type=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en

[8] “Opening public procurement to SMEs", European Commission Enterprise and Industry DG - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/public_procurement.htm

[9] “Evaluation of SMEs access to public procurement" Final Report produced by GHK and Technopolis on behalf of European Commission Directorate General Enterprise and Industry http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/docs/SME_public_procurement_Summary.pdf

[10] Annex to Final Report “Evaluation of SMEs access to public procurement" produced by GHK and Technopolis on behalf of European Commission Enterprise and Industry DG, Section on United Kingdom - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/docs/SME_public_procurement_Annex.pdf

[11] Annex to Final Report “Evaluation of SMEs access to public procurement" produced by GHK and Technopolis, Section on United Kingdom - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/docs/SME_public_procurement_Annex.pdf

[12] “Evaluating SME experiences of Government procurement", Report by Freshminds for the Scorecard Working Party – a joint initiative between the British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (BVCA), Federation of Small Businesses (FSB), and Confederation of British Industry (CBI), October 2008.

[13] “Europe’s social economy", European Commission Enterprise and Industry DG - http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/public_procurement.htm

[14] Social Economy Network briefing to Enterprise, Trade & Industry Committee, 13 November 2008.

[15] “Public Procurement – a guide for social economy enterprises", Central Procurement Directorate, Department of Finance & Personnel - http://www.cpdni.gov.uk/social-economy-enterprises-guidance-pdf.pdf

[16] Social Economy Network briefing to Enterprise, Trade & Industry Committee, 13 November 2008.

[17] Social Economy Network briefing to Enterprise, Trade & Industry Committee, 13 November 2008.

Research and Library Services

_fmt2.jpeg)

24 February 2009

Public Procurement and the Social Economy

Dr Robert Barry & Aidan Stennett

This briefing paper looks at some of the barriers encountered by Social Economy Enterprises (SEEs) in securing public procurement contracts. It also draws some lessons on the use of social clauses from experiences in Scotland and the Cabinet Office’s Social Clauses Project

Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of The Assembly and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public.

Contents

Summary of Key Points xx

Social Economy Sector xx

Introduction xx

The Northern Ireland Social Economy xx

Problems Facing SEEs in Securing Public Procurement Contracts xx

The EU Legal framework xx

The Use of Social Clauses xx

The Use of Social Clauses in Scotland xx

Community Benefits in Public Procurement in Scotland xx

Cabinet Office Social Clauses Project xx

Conclusion xx

ANNEX A: Public Procurement Expenditure by Category xx

ANNEX B: Scottish Government’s Model Community Benefit Clauses xx

Summary of Key Points

Social Economy Sector

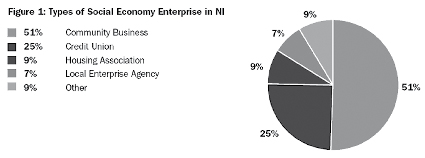

- There are around 600 Social Economy Enterprises in Northern Ireland, employing somewhere in the region of 10,000 people.

- About half of these are community businesses; around a quarter are credit unions; and the remaining quarter is made up of housing associations, local enterprise agencies and ‘others’.

Problems faced by Social Economy Enterprises in Public Procurement

- Difficulties in finding information about tenders.

- Difficulties in finding information about the procedures for bidding.

- Problems in understanding jargon.

- Too short a deadline for responding.

- Costs of responding too high.

- Administrative procedures too complex/onerous paperwork requirements.

- Particular certification required for some contracts.

- High financial guarantee required for some contracts.

- Over-emphasis placed on price by awarding authorities.

- Discrimination because of location.

- Length of time the process takes.

- Pressure on public bodies to secure efficiencies by aggregating contracts and using Framework Agreements (similar to call-off lists, which tend to favour larger organisations).

- Uncertainties on the status of social clauses and EU procurement rules.

- Difficulties in formulating social clauses as a core contractual requirement.

- Difficulties in measuring social value.

Lessons from Scottish Experience

- Social issues should be considered at the outset, at the advertising stage, at the selection stage, and after the contract is awarded.

- Social issues may be addressed under the ‘duty to promote’ in equality legislation.

- Under public procurement legislation public bodies may restrict participation in a tendering exercise to only those organisations defined as supported businesses.

- Targeted recruitment and training can be achieved without negatively affecting value for money requirements.

Lessons from Cabinet Office Project

- Further guidance on the use of social clauses is required to clarify the processes and the legal issues under European and UK procurement policies.

- Social clauses must be tailored so that they relate to the performance of the specific contract and must offer value for money.

Introduction

Public procurement policy in Northern Ireland is the responsiblility of the Procurement Board chaired by the Minister of Finance and Personnel. Membership of the Board comprises the Permanent Secretaries of the 11 Government Departments, the second Permanent Secretary in OFMDFM, the Treasury Officer of Accounts, 2 external experts without a specific sectoral interest, the Director of the Central Procurement Directorate and a representative of the Comptroller and Auditor General as an observer.[1]

The Central Procurement Directorate, within the Department of Finance and Personnel, is the core professional procurement body. It is responsible for developing policy and supporting the Procurement Board’s role in all aspects of public procurement policy. The Directorate will where appropriate directly procure strategic requirements, provide expertise, advice and a coordinating role.

In addition to the Directorate there are a number of centres with specialist procurement expertise across the public sector (including the Education and Library Boards and a number of public bodies and agencies).[2] The Executive is of the view that considerable added value can be derived from these Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs), both in developing operable policies and providing a more integrated procurement service to public bodies in general.

Departments, their Agencies, NDPBs and public corporations are expected to carry out their procurement activities by means of documented Service Level Agreements with the Central Procurement Directorate or a relevant Centre of Expertise.

The public sector in Northern Ireland spends around £2 billion each year on public procurement. Most of this, however, is spent on road maintenance, major construction work, medical/surgical equipment and supplies, consultancy services, energy and other areas where Social Economy Enterprises (SEEs) would not normally be involved or in a position to compete (see Annex A for a breakdown of procurement expenditure by Departments, their Agencies and Non-Departmental Public Bodies by category and by Department over the last three years).[3]

The Northern Ireland Social Economy

A Social Economy Enterprise is defined by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI) as ‘a business that has a social, community or ethical purpose, operates using a commercial business model and has a legal form appropriate to a not-for-personal profit status’.[4] Based on this definition, only 396 organisations in Northern Ireland identified themselves as SEEs in response to a DETI survey carried out in 2006/07. An earlier UK-wide survey, however, estimated a total of around 600 SEEs in Northern Ireland.[5] Given the 61% response rate to the DETI survey, the figures are in fact consistent and an estimate somewhere around 600 for the total number of SEEs in Northern Ireland seems reasonable. Based on the DETI survey figures, the total number of paid employees in these enterprises is likely to be somewhere around 10,000.[6]

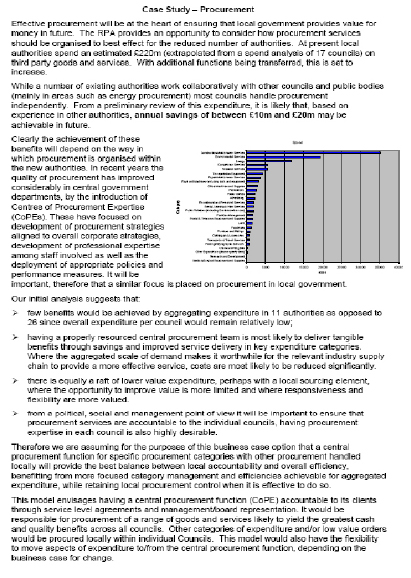

The DETI survey also provided some useful information on the nature of these enterprises (see Figure 1 below for a breakdown by type). On average, two-thirds of the income of SEEs was earned from trading activities, while 28% was received from grants and donations and 4% came from other sources. Most of them (73%) reported an annual turnover of less than £500k.

Source: DETI

Problems Facing SEEs in Securing Public Procurement Contracts

Many SEEs are simply not in a position to compete for public procurement contracts because of their size or because they simply do not provide the type of services that Government Departments are looking for e.g. Credit Unions, Housing Associations, or organisations offering local training/education or child care. Those who are in a position to compete for some Government work face similar problems to those faced by all small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs):[7]

- difficulties in finding information about tenders

- difficulties in finding information about the procedures for bidding

- problems in understanding jargon

- too short a deadline for responding

- costs of responding too high

- administrative procedures too complex/onerous paperwork requirements

- particular certification required for some contracts

- high financial guarantee required for some contracts

- over-emphasis placed on price by awarding authorities

- discrimination because of location

Some additional problems faced by SEEs who have successfully secured tenders for the delivery of services include the length of time the process takes, and the potential impact of Departmental efficiency savings, which although not intended to affect front line services may do so in some cases. It is also argued that pressure on public bodies to secure efficiencies by aggregating contracts and using Framework Agreements (similar to call-off lists) will discriminate against small businesses, including many social enterprises.

The Social Economy Network (SEN), in its recent presentation to the Enterprise, Trade and Investment Committee, proposed the following actions to help SEEs:

- Inclusion of social clauses into public procurement specifications to ensure a more equal playing field;

- Adoption of a consistent approach to the measurement of social value which can be embedded in the practice and processes of public procurement; and

- Exploration of innovative ways of increasing business opportunities for SEEs through public/social partnerships and private/social partnerships.[8]

The EU Legal framework

The EC Treaty applies to all public procurement activity regardless of value, including contracts below the thresholds at which advertising in the Official Journal of the European Union is required and including contracts which are exempt from application of the EC Procurement Directives.

Fundamental principles arising from the Treaty include:[9]

- transparency - contract procedures must be transparent and contract opportunities should generally be publicised;

- equal treatment and non-discrimination - potential suppliers must be treated equally;

- proportionality - procurement procedures and decisions must be proportionate;

- mutual recognition - giving equal validity to qualifications and standards from other Member States, where appropriate.

EC Procurement Directives 2004/17/EC and 2004/18/EC set out detailed procedural rules which are based on the principles outlined in the EC Treaty and which are intended to support the single market by harmonising procedures for higher value contracts, ensuring that they are advertised in the Official Journal of the European Union in standard format.

The EU Public Procurement Directive (2004/18/EC) and the Utilities Procurement Directive (2004/17/EC) were implemented in England, Wales and Northern Ireland by the Public Contracts Regulations 2006 and the Utilities Contracts Regulations 2006, which came into force on 31 January 2006.

The Use of Social Clauses[10]

Social clauses have been defined by the Cabinet Office as:

“...requirements within contracts or the procurement process which allow the contract to provide added social value through fulfilling a particular social aim. For example, a social clause in a public contract could prioritise the need to train or give jobs to the long-term unemployed in the community as part of the contracting workforce."[11]

Social clauses need to be carefully considered to ensure that they meet the requirements of EU procurement rules and general EU law. Such clauses should not give rise to direct or indirect discrimination. Contracting authorities must have a legal and policy basis for incorporating social benefit requirements into their procurement processes.

The Office of Government Commerce (OGC) has produced guidance on how to address social issues in public procurement. The guidance points out that “all public procurement is required to achieve value-for-money and is subject to the principles of the EC Treaty, around a level playing field for suppliers from the UK and other member states, and the UK regulations implementing the EC Public Procurement Directives." In addition, OGC recommend that:[12]

- Social issues addressed in procurement should be relevant to the subject of the contract.

- Actions to take account of social issues should be consistent with the government’s value-for-money policy, taking account of whole-life costs.

- Any social benefits sought should be quantified and weighed against any additional costs and potential burdens on suppliers, which are likely to be passed onto the public sector.

- Contracting authorities should be careful not to impose unnecessary burdens that would seriously deter suppliers, especially small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), from competing for contracts.

- They should also consider whether any social legislation, such as public sector equality duties, are relevant to a procurement and take appropriate action to address this.

The Use of Social Clauses in Scotland

The Scottish Executive’s Public Procurement Handbook addresses social inclusion by making it mandatory for public bodies to:

“…pro-actively manage and develop the supplier base, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and third sector and voluntary sector organisations, identifying and managing any supply risks or value added opportunities".[13]

The clause forms part of the Executive’s drive to ensure “social issues" are taken into consideration during public procurement processes. The term social issue in this context is broadly defined as:

“Issues which impact on society or parts of society and cover a range of issues including equality issues (i.e. age, disability, gender, race, religion and sexual orientation), training issues, minimum labour standards and the promotion of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), including black and minority ethnic enterprises and the third sector including social enterprises." [14]

Overriding this social issues imperative is the prioritisation of Value for Money (VFM). VFM is considered to go beyond cost implications and is more broadly interpreted to include: “the best possible balance between price and quality in meeting the customer’s requirements". Such requirements must include the promotion of sustainable development and corporate social responsibility, which includes social, economic and environmental objectives, including:

- social elements, such as, the “duty to promote" under discrimination legislation;

- economic issues, such as, removing barriers preventing social enterprises, local suppliers and SMEs competing for public business;

- supported businesses – under public procurement legislation public bodies may restrict participation in a tendering exercise to only those organisations defined as supported businesses;[15]

- fair trade issues – whilst it is not permissible to specify in a tender opportunity that only fair trade options will be offered public contracts, it is permissible to say that fair trade options would be welcome;[16] and

- environmental considerations such as conserving resources, reducing waste, phasing-out ozone depleting substances, encouraging the use and manufacture of environmentally friendly materials, sourcing material from sustainable resources and meeting regulatory environmental codes, should all form part of the procurement process.[17]

An example of where the consideration of social issues during the procurement process is likely to be appropriate is where a public authority has obligations of a social nature in relation to a particular function, the performance of which it is contracting out. For example the “duty to promote" under discrimination legislation can legitimately be passed on to a contractor where the contractor is carrying out a service which would have been subject to the duty were it being performed in-house.[18]

In addition to the above, there may be occasions where the procurement process might consider “wider social benefits". An example of such a consideration is the awarding of grants for an urban regeneration project and evaluating how those contracts might aid the regeneration project itself, by providing training opportunities for the unemployed.[19]

The Scottish Government recommends that social issues should be considered during the following stages of the procurement process:

- at the outset, to ensure the social dimension is fully taken into account when requirements are drawn up;

- at the advertising stage;

- at the selection stage, where thought should be given to ensure the target audience is aware of requirements and how to respond; and

- after the contract is awarded, where cooperation with contractors can help to improve the social focus and send a “clear signal to suppliers about the public body’s objectives in this area".[20]

Community Benefits in Public Procurement in Scotland

In the context of public sector procurement community benefits are “contractual requirements which deliver a wider social benefit in addition to the core purpose of the contract". Community benefit requirements often have particular focus on training and employment outcomes. Since 2003 the Scottish Government has operated a pilot programme to examine the operation of community benefit issues in a practical context. The pilot scheme operated across five authorities; Glasgow Housing Association; Ralpoch Urban Regeneration Company; Inverclyde Council; Dundee City Council; and Falkirk Council. The findings of the pilot scheme where recently published in the Community Benefits in Public Procurement report (2008).

The report outlines a number of model clauses which may act as a guide to public bodies. The clauses, which cover procurement policy statements, procurement strategies, pre-qualification questionnaires and specifications, are outlined in Annex B.

The pilot projects outlined in the report serve as case studies for the wider community benefit programme. A brief synopsis of each programme is provided followed by an overview of the pilot’s findings.

Glasgow Housing Association (GHA) - GHA’s medium-term procurement strategy, which was utilised during a large-scale regeneration programme, established the following principles:

- each building supplier or contractor should make proposals for their commitment to employment and a ‘partnership training initiative’;

- GHA’s Neighbourhood Renewal Team should advise and support the procurement process to that it maximises social and economic benefits;

- GHA will not be the main funder of social and economic initiatives but would act as an enabler and facilitator.

Raploch Urban Regeneration Company – Raploch is an area of Sterling noted for below average incomes, low levels of qualifications and high unemployment. The area is also home to poor quality public sector buildings and environment (including housing and health) due to proximity to the city’s road network. Raploch Urban Regeneration Company was established to address these problems. The group’s vision, outlined in their 2004 corporate plan is to “build a community where people want to live, work and visit… within an economically sustainable environment". The vision outlined in the corporate plan (which includes ambitious education, employment and average income targets for the period 2004 – 2012), has resulted in the inclusion of targeted recruitment and training requirements in the group’s procurement processes and documentation.

Inverclyde Council – The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (2004) notes that Inverclyde has the second highest concentration of deprivation, next to Glasgow. The key factors which have resulted in this deprivation where identified as health, unemployment, education and income. The regions problems led to it being selected amongst the Scottish Executive’s “Closing the Opportunity Gap" areas. The aim of the initiative is to reduce the number of people on benefits from 12,100 (2004) to 3,000 (2010). The strategic framework for achieving this target was set out in the Inverclyde Alliance’s Regeneration Outcome Agreement and the Councils Economic Development Strategy. Amongst the strategies stated aims is the following:

“For Inverclyde to achieve sustainable economic progress, it is vital that residents and communities are connected to economic opportunities and feel able to contribute to and benefit from them".

This led the council to target the recruitment and training opportunities arising from its development and investment activities towards social development for the first time.

Dundee City Council – Dundee Council’s application of community benefit principles is based upon powers conferred on it through the Local Government in Scotland Act 2003. Prior to implementing its community benefit pilots the council established the “Community Benefits in Procurement Group". The group, made up of numerous local actors in the social sector, agreed to run pilots in the construction and social care sectors.

Falkirk Council – Falkirk Council’s strategic aim is to mainstream community benefits across all its policy mechanisms. The initial step of this process was the appointment of consultants who began by examining the council’s procurement expenditure, with the ultimate result of outlining a set of “Organisational Strategic Objectives" designed to expand community benefits. These included:

- increasing the level of spend with local suppliers across all areas of procurement;

- increasing the percentage of local labour used in Council contracts;

- achieving an increase in youth attainment;

- decreasing the level of long-term unemployment;

- increasing the number of training opportunities in the local area;

- increasing inward investment; and

- embedding community benefit requirements in the procurement process to ensure they are viewed as an integral, rather than a separate, initiative.

The relative success or failure of the above projects was measured across a number of factors: the organisation’s culture and resources; their ability to clearly demarcate roles and responsibilities; the clarity of requirement specification; developing a systematic approach, particularly in incorporating targeted recruitment and development; developing an appropriate supply-chain; and preventing training and funding mismatches. The report noted that the length of the contract may also indirectly determine its success, particularly when the timetable is uncertain.

Based on this analysis, the report sets out a number of key findings across specific areas.

- Targeted Recruitment and Training (TRT) – TRT may be achieved without negatively affecting VFM requirements, however success depends upon:

- high-level commitment to the new approach which leads to changes in cultures and practices within procurement teams;

- a commitment of resource by the client body. In this area the best deployment of resource was deemed to be the employment of a “Project Champion" to act as an advisor to the procurement team.

- Achieving Community Benefits – the drafting of Community Benefits Requirements should take into account;

- the objectives of Community Benefit Clauses;

- the design of requirements to fit with supply side funding and services;

- the monitoring and reporting requirements which will enable the contracting authority to use the above effectively.

- Alignment of TRT with existing services – Community Benefits Requirements should allow contractors to utilise existing training and job matching services. Difficulties may arise, however, should inclusion of Community Benefits require existing providers to change their working methods.

- Commissioning Skills – Community Benefits Requirements necessitates the development of skills amongst the procurement’s stakeholder group. Not least in developing an understanding of the “entitlement to procure".

Cabinet Office Social Clauses Project

The Partnership in Public Services Action Plan was launched in 2006 by the Cabinet Office to enable an increase in public service delivery by the third sector.[21] The action plan identified four different elements of the government’s engagement with the third sector: commissioning; procurement; learning from the third sector; and accountability.[22]

The action plan required the Office of the Third Sector to examine the use of social clauses, barriers to their use, and the potential for template clauses. The social clauses project was consequently established in conjunction with the North East Centre of Excellence.

The aims of the project were to: consolidate knowledge on the existing use and best practice of social clauses; provide clarity on the merits of using social clauses; and support good commissioning and procurement by producing user friendly materials to help decision makers.

The main barriers to the use of social clauses were identified as confusion about when they can be legally used, concern about the processes needed to include them in any contract specification and how to evaluate them.

Survey results confirmed that legal uncertainties on the status of social clauses and EU procurement rules, as well as lack of information and understanding, were barriers to their use. Additionally, stakeholders reported difficulties in formulating social clauses as a core contractual requirement, and difficulty in measurement at the evaluation stage.

Some survey recipients suggested that further guidance on the use of social clauses was needed from central government in order to clarify their use and the legal issues under European and UK procurement policies.

Feedback was also obtained from comments received from individuals, phone interviews with local authorities and discussions which were held with a wide range of agencies. Based on this feedback, it was decided that the creation of template clauses should not be considered, as it seemed clear to the project team that any contract terms need to be tailored to the particular procurement, must relate to the performance of the specific contract and be assessed on whether their inclusion represents value for money.

The project therefore moved from the original aim in the action plan of creating template contract conditions to exploring how and when social issues could be addressed in the procurement process and what package of support should be created for commissioners looking to address social issues through procurement activities.[23]

Conclusion

Problems faced in public procurement by SEEs are similar to those faced by SMEs. Whilst the use of social clauses would certainly help their position, there appear to be some uncertainties on the status of social clauses and the potential conflict with EU procurement rules. Contractors have also reported difficulties in formulating social clauses as a core contractual requirement and difficulties when it comes to measuring social value.

Some useful lessons can perhaps be learned from the Scottish experience. It has been shown, for example, that targeted recruitment and training can be achieved without negatively affecting value for money requirements. The Scottish Government have also set out a number of ‘model’ social clauses to act as a guide to public bodies.

The Cabinet Office Social Clauses Project identified some confusion about when social clauses can be legally used, and also concern about the processes needed to include them in any contract specification and how to evaluate them. This suggests, as was felt by some participants in the project, a need for further guidance on the use of social clauses in order to clarify the processes and the legal issues under European and UK procurement policies.

Annex A: Public Procurement Expenditure by Category

Procurement Expenditure incurred by Departments, Agencies and NDPBs

|

Category |

2005/06 |

2006/07 |

2007/08 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Construction/Maintenance Services |

794 |

711 |

897 |

|

Medical/Surgical Equipment and Supplies |

187 |

186 |

235 |

|

Consultancy Services |

121 |

102 |

115 |

|

Energy |

100 |

125 |

140 |

|

Public Utilities |

77 |

71 |

|

|

Transport and Travel Services |

53 |

63 |

72 |

|

Repair/Maintenance Services |

53 |

60 |

67 |

|

Plant and Machinery (including tools and equipment) |

45 |

43 |

59 |

|

Facilities Management |

44 |

52 |

63 |

|

Rental, Leasing or Hire Services |

42 |

24 |

54 |

|

Office Machines and Supplies |

41 |

72 |

99 |

|

Transportation Equipment |

30 |

61 |

78 |

|

Postal and Telecoms Equipment and Supplies |

29 |

35 |

36 |

|

Food Stuffs |

27 |

27 |

37 |

|

Chemicals/Reagents |

23 |

21 |

21 |

|

Financial Services |

22 |

17 |

21 |

|

Furniture and Fittings |

13 |

17 |

19 |

|

Printing/Reprographic Services |

13 |

14 |

14 |

|

Environmental Services |

11 |

10 |

14 |

|

Publications |

10 |

14 |

24 |

|

Clothing and Accessories |

7 |

7 |

8 |

|

Land |

|

|

19 |

|

Advertising |

|

|

16 |

|

Recruitment and Personnel Services |

|

|

15 |

|

Research and Development |

|

|

8 |

|

Public Relations (including events/conferences) |

|

|

6 |

|

Other Expenditure |

70 |

162 |

65 |

|

Totals |

1812 |

1895 |

2202 |

Source: Central Procurement Directorate Annual Reports to Procurement Board

Annex B: Scottish Government’s Model Community Benefit Clauses

The following model clauses are recommended for use as a starting position for procurements.[24] They are drafted on the basis that the contractor will have supplied a service delivery plan/method statement satisfactory to the Authority, concerning how they will generate training and employment opportunities. Alternative clauses may be drafted depending on the requirements that have been included in the specification.

- The [Contractor/Developer] agrees to secure the creation of training opportunities in connection with the [Project] of a total of [number] training weeks in accordance with the [Service Delivery Plan/Method Statement for economic development activities].

- The [Contractor/Developer] agrees to secure the creation of at least [number] employment opportunities in connection with the [Project] which are aimed specifically at [detail target group, for example, people who have been unemployed for at least 6 months (including people who first take advantage of training opportunities created under Clause X.1)] and use all reasonable endeavours to fill those posts with such persons.

- The [Authority] undertakes to assist the [Contractor/Developer] and their sub-contractors to provide training and employment opportunities by providing lists of agencies that can assist in the recruitment of suitable trainees/employees, and the identification of potential sub-contractors and suppliers. Any action taken by the Authority or their agents does not imply, and must not be deemed to imply any promise to provide suitable labour/firms/agencies, and does not imply and must not be deemed to imply that any individuals/ firms/agency referred to the contractors or sub-contractors are suitable for engagement.

- The Contractor is required to complete weekly labour monitoring forms in a format to be provided by the Authority, and is responsible for obtaining accurate data from all sub-contractors on site for entry onto the forms. The weekly labour monitoring form must be completed and supplied to the Authority or their agent within 7 days of the end of the week to which it relates.

- To the extent it has not already done so the [Contractor/Developer] shall enter, and shall procure that its Sub-Contractors enter, into the [enter name] Construction Initiative’s Employment Charter at the same time as entering into this Agreement.

[1] DFP Public Procurement Policy Summary Statement - http://www.cpdni.gov.uk/pdf-public_procurement_policy_summary.pdf

[2] See http://www.cpdni.gov.uk/index/current-opportunities.asp/centres-of-procurement-expertise.htm

[3] Based on information provided by DFP Central Procurement Directorate Annual Reports.

[4] “Findings from DETI’s First Survey of Social Economy Enterprises in Northern Ireland", DETI, July 2007 - http://www.detini.gov.uk/cgi-bin/downutildoc?id=1967

[5] “A Survey of Social Enterprises Across the UK", Research Report prepared for the Small Business Service by IFF Research Ltd, July 2005 - http://www.socialeconomynetwork.org/PDFs/Publications/SurveySEAcrossUK.pdf

[6] The total number of paid employees in the 396 SEEs surveyed was 6,683.

[7] See Assembly Research Paper 119/08 “Public Procurement and SMEs" - http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/io/research/2008/11908.pdf

[8] Social Economy Network briefing to Enterprise, Trade & Industry Committee, 13 November 2008.

[9] Source: Scottish Government Public Procurement Handbook - http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/256155/0076031.pdf

[10] See also NI Assembly Research Paper 03/09 “Social Clauses in Public Contracts", February 2009 –

http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/io/research/2009/0309.pdf

[11] Cabinet Office - http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/third_sector/public_services/social_clauses.aspx

[12] Office of Government Commerce, “Buy and make a Difference: How to Address Social Issues in Public Procurement" -

http://www.ogc.gov.uk/documents/Social_Issues_in_Public_Procurement.pdf

[13] Scottish Government Public Procurement Handbook - http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/256155/0076031.pdf p8

[14] The Scottish Government Social Issues in Public Procurement: A guidance note by the Scottish Procurement Directorate - http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/116601/0053331.pdf

[15] Businesses with more than 50% of the workforce being disabled, who, by reason of their disability, are unable to take up work on the open labour market

[16] The Scottish Government Sustainable Procurement summary note

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Government/Procurement/policy/corporate-responsibility/susdevsummarynote (accessed 03/02/09)

[17] The Scottish Government Public procurement and sustainable development http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Government/Procurement/policy/corporate-responsibility/13744#a4 (accessed 03/02/09)

[18] Scottish Government Broad Summary Note on Sustainable Procurement -

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Government/Procurement/policy/corporate-responsibility/susdevsummarynote

[19] The Scottish Government Social Issues in Public Procurement 0 A guidance note by the Scottish Procurement Directorate

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/116601/0053331.pdf (accessed 02/02/09)

[20] The Scottish Government Social Issues in Public Procurement 0 A guidance note by the Scottish Procurement Directorate

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/116601/0053331.pdf (accessed 02/02/09)

[21] Cabinet Office, Office of the Third Sector -http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/third_sector/public_services/public_service_delivery.aspx

[22] Cabinet Office, Office of the Third Sector, Report of the Social Clauses Project 2008 -

http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/107238/social_clauses_report_final.pdf

[23] Cabinet Office, Office of the Third Sector, Report of the Social Clauses Project 2008 -

http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/107238/social_clauses_report_final.pdf

[24] Scottish Government “Community Benefits in Public Procurement", February 2008 -

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/212427/0056513.pdf

Research and Library Services

_fmt3.jpeg)

Research Paper

01 May 2009

The Integration of

Social Issues in

Public Procurement

Colin Pidgeon

Research Officer

Research and Library Service

The integration of social issues into public procurement has been an issue of interest in Northern Ireland for some years. This paper seeks to provide relevant information for the Committee for Finance and Personnel’s inquiry into public procurement by setting out the legal framework and drawing on experience from other parts of Europe.

Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of The Assembly and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public.

Key Issues

- The European legal framework for public procurement allows the integration of social issues. But care must be taken in how this achieved to avoid infringing the procurement Directives or the fundamental principles.

- There have been some examples of the use of social clauses in Northern Ireland. An unemployment pilot project appears to have been successful and the Central procurement directorate continues to use similar contractual provisions.

- The difficulty of monitoring compliance with contractual clauses is a recurring theme across Europe. This was also raised by CPD officials in their evidence session to the Committee of Finance and Personnel on 19 April 2009.

- An integrated approach to encourage social inclusion is taken in France. Contractors can be assisted by facilitators with experience of the particular social needs of certain sections of the community. The facilitator, paid by social service agencies, not only helps firms to manage the integration element of the workforce but also monitors implementation of the clauses.

- There is a relatively high level of policy commitment to using social clauses in Northern Ireland. It is questioned the extent to which this has been translated into their use in practice. There have been a number of legal challenges to the public procurement process which may have led to contracting authorities being cautious. It is also possible that a level of inertia in the system has led to uptake of their use being slow.

- In France there is also a high level of policy commitment. But the domestic courts have interpreted European requirements very strictly (due in part to a legal heritage that places great weight on “egalité") and has struck down some contract awards. Legal and cultural heritage appears to be important in this respect - the Italian courts, for example, take a much less strict view. An understanding of how the Northern Ireland courts have interpreted social clauses in contracts may be beneficial.

- The case studies in Northern Ireland do not indicate a use of variant tenders – allowing for parallel bids to be submitted with higher levels of social integration than the minimum. This approach is seen as useful in some Member States.

- It is for Member States to determine what constitutes ‘grave professional misconduct’ - which allows for potential bidders to be excluded if they do not meet the level of social compliance determined. It may be that there are certain objectives in the Executive’s Programme for Government that could be strengthened by procurement policy taking them into account – for example, the use of child or forced labour in the supply chain.

Contents

1. Introduction xx

2. The European Legal Framework For Procurement xx

2.1. Directive 2004/18/Ec on the Coordination of Procedures for the

Award PF Public Works Contracts, Public Supply Contracts and Public Service Contracts xx

2.2. The Stages of Procurement and the Integration of Social Considerations xx

3. Experiences From Other EU Member States xx

3.1. Denmark xx

3.2. Germany xx

3.3. France xx

3.4 Italy xx

3.5 Public Private Partnerships: A Case Study from the Netherlands xx

4. Northern Ireland xx

4.1 Legal Issues in Northern Ireland xx

4.2 Case Studies in Northern Ireland xx

5. The Uk Cabinet Office Social Clauses Project xx

5.1 Pilot Projects xx

5.2 Social Return on Investment xx

1. Introduction

The integration of social considerations into public procurement has been on the European agenda for quite some time. The Commission issued an Interpretative Communication on the topic as far back as autumn 2001. This was intended to clarify the range of possibilities for integrating social considerations under the Community legal framework that was in operation at that time.

Since that time European law on public procurement has been updated. The Directives that are most relevant are what is known as the “classic" or “public sector" Directive[1], and the “utilities" Directive of 2004.[2] Above and beyond the specific provisions of the Directives, there are fundamental principles with which all procurement exercises must comply.

Fundamental principles deriving from Treaty provisions:

- Equality of treatment

- Obligation of transparency

- Proportionality

- Mutual recognition

One means of integrating social considerations into public procurement is through the use of ‘social clauses’. The terms of reference for the Committee for Finance and Personnel’s inquiry into public procurement practice in Northern Ireland include consideration of ‘the nature, extent and application of social clauses within public contracts’.

There is some policy commitment to such integration both within the devolved government of Northern Ireland and at the UK level. The Office of the Third Sector (within the Cabinet Office) has undertaken a study examining the use of social clauses, barriers to their use, and the potential for template clauses.[3]

The Cabinet Office has defined social clauses as:

…requirements within contracts or the procurement process which allow the contract to provide added social value through fulfilling a particular social aim. For example, a social clause in a public contract could prioritise the need to train or give jobs to the long-term unemployed in the community as part of the contracting workforce.[4]

The Northern Ireland Executive’s Programme for Government (PfG) for 2008-11 contains commitments that indicate support for the use of social clauses in appropriate circumstances. In relation to the Executive’s reform programmes, for example, the PfG states that:

We are committed to taking forward key reform programmes in areas such as health, education, water and planning and will shortly announce our plans for the reform of local government. These will result in significant changes to both the structure and the delivery of public services, reducing bureaucracy and enabling us to focus our energy and resources on frontline services. We will ensure that the reforms and restructuring will be compliant with recognised best practice in social procurement guidelines.[5]

The Central Procurement Directorate (CPD) of DFP has included the need to consider the social aspect of procurement in its twelve guiding principles for purchasers. The seventh principle states:

Integration: in line with the Executive’s policy on joined-up government, procurement policy should play due regard to the Executive’s other economic and social policies, rather than cut across them.[6]

Across Europe there are different levels of emphasis on the integration of social considerations into public procurement. In some instances (notably in Germany) there is some interest in pursuing not just the domestic social agenda but also wider social issues such as Fair Trade and the prevention of child labour.

This paper considers the European legal framework and issues that relate to the use of social clauses. It also details some case studies from across the EU and concludes with some case studies from Northern Ireland and elsewhere in the UK.

2. The European Legal Framework for Procurement

Procurement represents about 16% of EU gross domestic product (GDP) and in 2007 the value was estimated at €2,000 billion (including procurements both above and below EU thresholds) and in 2006 nearly 32,000 contracting authorities published public contracts worth €380 billion.[7] It is perhaps not surprising then that the EU has legislated significantly in the field of public procurement for a number of years. It is seen as an important single market issue.

At around 3% of total procurement, direct cross-border procurement is relatively low. (Direct cross-border procurement is where a company based in Germany, for example, wins a contract in the Netherlands.) When indirect cross-border procurement is also considered (this includes, for example, a French national company with a subsidiary in Spain wins a contract in Spain) it accounts for around 10%.[8] With free movement of goods being a fundamental purpose of the European Union, this is perhaps surprisingly low.

There are three aspects of EU law that apply to procurement. Primary law is essentially the Treaty; secondary law is the various relevant Directives, and; case law of the European courts. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) often places importance on free movement because there is a clear legal basis to do so in the EC Treaty.

The establishment of a single market is the key factor in relation to procurement: all other objectives (such as sustainability) are secondary. As a result, there remains a tension between the single market and the social policy arenas. The EU has limited competence in the social area which has caused problems of legal uncertainty for procurement practitioners.[9] It is notable that this is less the case in the environmental area and there have been direct interventions by the European Commission – for example the Energy Labelling Directive and the Energy Performance in Buildings Directive.

The ‘fundamental principles’ are important because it is possible that social or ethical considerations could operate as a disguised barrier to the free movement of goods, and therefore become a form of protectionism. For example, a technical specification of goods to be provided which refers only to a national standard (for example, a British Standard in construction) would be discriminatory unless it allows equivalent standard from other Member States. It is therefore essential that contracting authorities pay attention to these principles in their procurements or they run the risk of legal challenge.

2.1 Directive 2004/18/EC on the Coordination of Procedures for the Award of Public Works Contracts, Public Supply Contracts and Public Service Contracts

This is the so-called “classic" or “public service" directive. Amongst other things, it deals with the scope of application (thresholds, specific situations and exclusions, and special arrangements), arrangements for public service contracts, technical specifications, procedures (open, restricted, negotiated or competitive dialogue) framework agreements, advertising and transparency, selection of contractors and the award of contracts.

Whether all or only some of the provisions of the Directive apply to a particular contract depends upon the objects of the contract. ‘Part A’ contracts are subject to the full procurement regime. ‘Part B’ contracts are subject to only some of the provisions. Health and social services are classified as ‘Part B’[10] so it is the more limited procurement regime that generally applies to the inclusion of social considerations if they are the subject of the contract. If, however, social considerations are included in a contract which itself is a ‘Part A’ contract, then the full regime applies.

Under the “classic" Directive it is possible for contracting authorities to state in a contract notice that a particular contract or element of the contract is to be reserved specifically for sheltered workshops or sheltered employment programmes. Such workshops or programmes are defined as those where “most of the employees concerned are handicapped persons who, by reason of the nature or the seriousness of their disabilities, cannot carry on occupations under normal conditions."[11] The Directive explains that “such workshops might not be able to obtain contracts under normal conditions of competition" and special provision is made because “sheltered workshops and sheltered employment programmes contribute efficiently to the integration or reintegration of people with disabilities in the labour market."[12]

It must be noted that the requirement for competition is not removed by this process of reserving contracts. A contract can’t be reserved for a particular sheltered workshop but for sheltered workshops in general, thereby allowing a number of such workshops to compete for the tender.

For contracts that the contracting authority does not choose to reserve, there is varying scope to address social issues (which are relevant to but not the direct purpose of the procurement) depending on the stage of the public procurement process. The UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC) sets out those stages as follows:

1. pre-procurement – when identifying the need, approaches and considering the market;

2. when deciding the requirement – the specification stage;

3. when selecting suppliers to invite to tender – the selection stage;

4. when awarding the contract – the award stage; and

5. in the performance of the contract – contract conditions and relationship management.[13]

2.2 The Stages of Procurement and the Integration of Social Considerations

The following section is set out in the order of the procurement processes set out by OGC.

A) the pre-procurement stage

This stage is when a contracting authority is considering what needs it wishes to fulfil and what benefits it wishes to define from the works, services or goods it is to purchase. Social issues may be addressed both through what is bought (for example, a service catering specifically for a particular group with specific social needs such as Irish travellers or young people with a history of offending) and less directly through how it is bought (for example, by making the requirement easily accessible to Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in particular communities).

OGC guidance specifies that in developing a business case, contracting authorities “should take account of wider benefits including social ones, in accordance with the Treasury Green Book."[14] (The ‘Green Book’ is the guidance that must be followed by departments in conducting economic appraisals and constructing business cases.) This is the stage when contracting authorities are able to consult widely with stakeholders to help them understand fully what is needed and consider which social issues or obligations are relevant to what they plan to buy. Additionally, this is the stage when consultation with potential suppliers will help contracting authorities to understand what the market can readily provide.

B) the specification stage

At this stage, the contracting authority sets out exactly what it is it wishes to buy. The specifications must be set out in all the relevant documentation – notices, contract documents, etc. Definitions of certain technical specifications are provided in the “classic" Directive. Specifications define the characteristics of a material, product or supply and “shall include levels of environmental performance, design for all requirements (including accessibility for disabled persons) and conformity assessment, performance, safety"[15] and other information such as dimensions, test methods, packaging, production methods and so on.

The specification should allow equal access for tenderers (due to the fundamental principles) and may contain references to technical characteristics or equivalents and/or output specifications. These outputs may concern environmental characteristics such as maximum levels of emissions, for example. But they may not specify a particular make, source, process, trade mark, patent or label. However, CPD guidance states that “Public bodies should not impose unnecessary burdens or constraints on suppliers or potential suppliers."[16]

Specifications must be relevant to the subject matter of the contract. OGC guidance states that “a social issue can be a core requirement and reflected in the specifications provided it is central to the subject of the procurement."[17] It gives an example of where the specification may require helpdesk staff to have fluency in languages other than English.

Also, an authority wishing to buy furniture made from fair trade wood could specify that wood should be sourced in accordance with specific environmental, social or employment standards. But it could not refer to a specific ‘fair trade’ label.

Variant tenders