Appendix 7

Public Procurement Stakeholder Conference

SRC - Introduction - 20 October 2009

SRC - Session 1 - 20 October 2009

SRC - Session 2 - 20 October 2009

SRC - Session 3 - 20 October 2009

SRC - Session 4 - 20 October 2009

Professor Christopher McCrudden

Comment on Stakeholder Conference Report

Buying Social Justice

Dr Aris Georgopoulos -

Comment on Stakeholder Conference Report

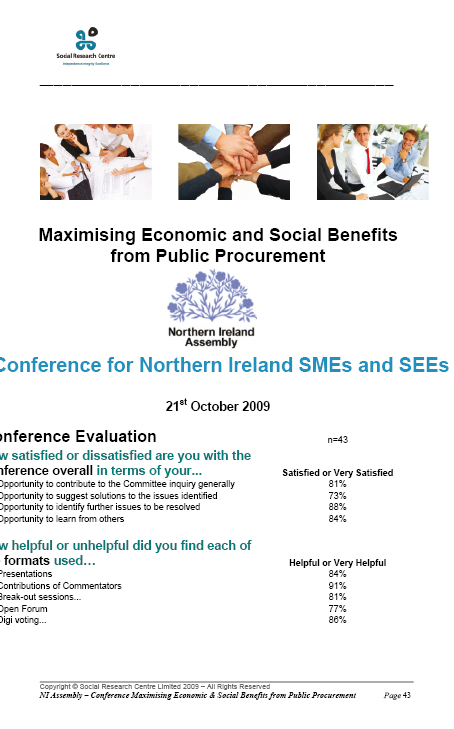

Maximising Economic and Social Benefits from

Public Procurement

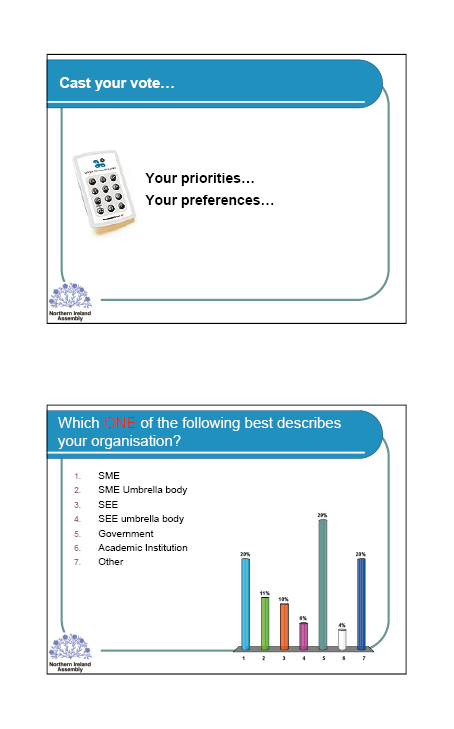

Conference for Northern Ireland Small Medium Enterprises (SME) and Social Economy Enterprises (SEE)

Contribution by Dr Aris GEORGOPOULOS

Lecturer in European and Public Law

University of Nottingham

School of Law

Public Procurement Research Group (PPRG)

aris.georgopoulos@nottingham.ac.uk

The present contribution deals with those points that emerged at the stakeholders’ conference and according to the author are of legal significance. The contribution follows the structure of the conference’s “summary report".

Comments on Points Raised:

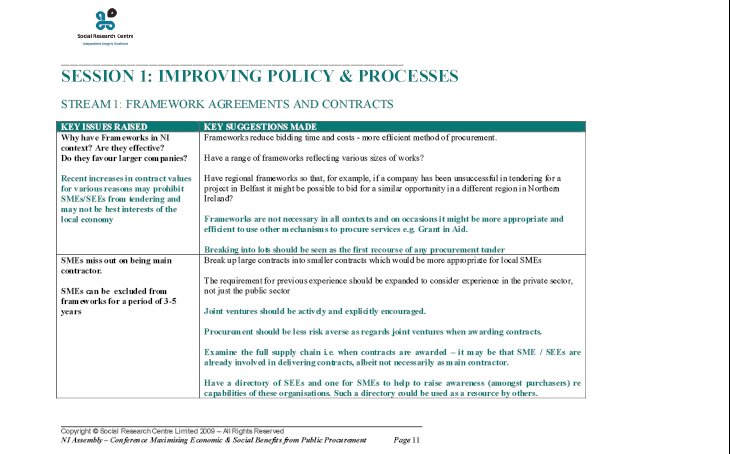

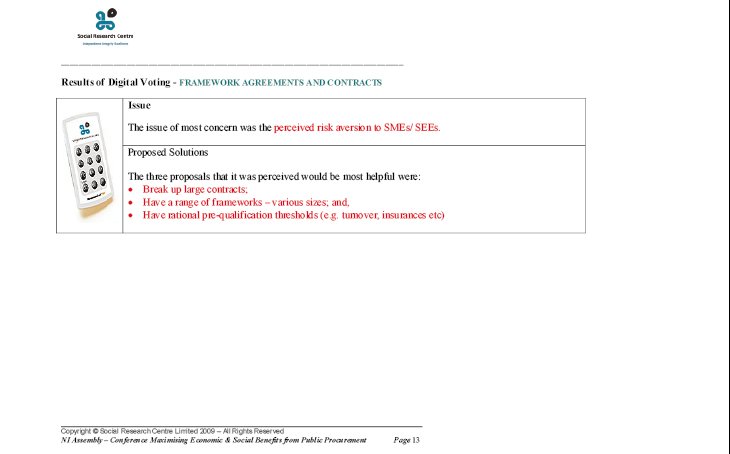

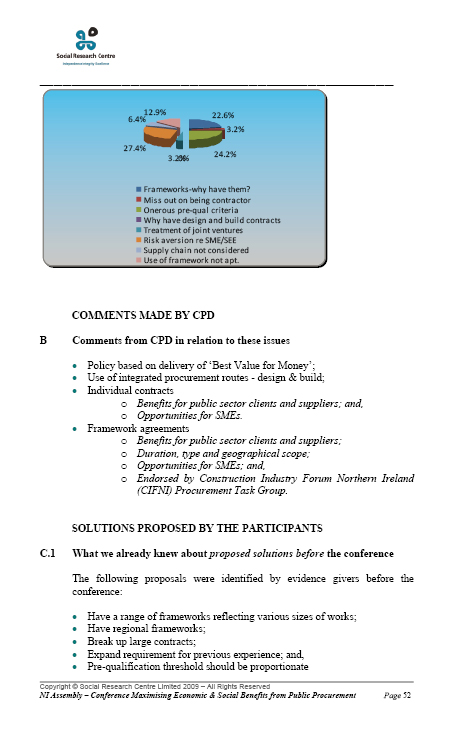

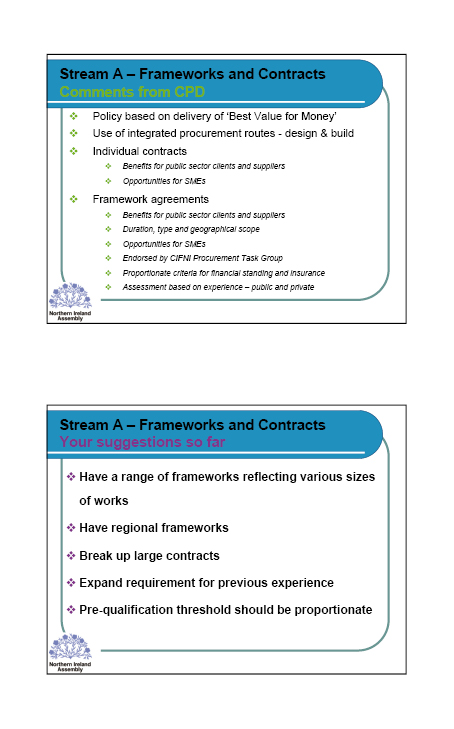

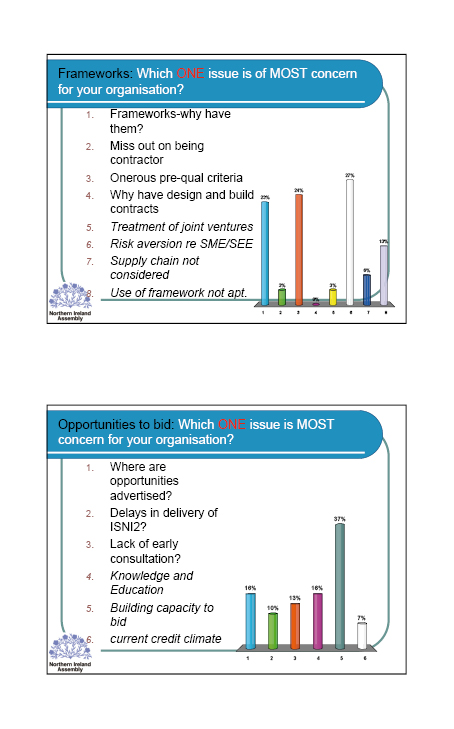

A. Stream 1: Framework Agreements and Contracts

- Framework agreements are indeed very useful and potentially beneficial for SMEs especially under the format of multi-supplier frameworks. Multi-supplier frameworks involve the conclusion of a framework agreement between one (or more) contracting authority and more than one provider. However it should be underlined that the mechanism of framework agreements is not a panacea and should be used for those kinds of contracts that due to their nature are better suited to benefit from the frameworks arrangement: for example contracts aimed to satisfy recurring needs for supplies and/or services etc.

- The proposal for having “regional frameworks" as a means to increase opportunities for SMEs (an unsuccessful SME in a procurement being able to bid for other similar opportunities in a different region in Northern Ireland) is an interesting one. From a legal perspective this could be achieved through the use of the “Central Purchasing Body" mechanism. However it should be noted that although the “regionalisation" of the use of frameworks through such bodies may lead to better value for money (better unit prices due to higher volumes) it may also attract more cross-border interest because of the higher financial opportunities involved thus increasing the competition for local SMEs.

- The EU Procurement Rules (Art. 9 (5) (a) Directive 2004/18/EC and Reg. 8 (12) Public Contracts Regulations 2006) allow the break up of contracts under certain conditions. In fact the rationale of these provisions is to encourage contracting authorities to provide opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises by dividing contracts into lots. This exemption is based on the following conditions:

a. the value of each of the (exempted) works contract is less than €1,000,000 (£810,580), or for supplies or services €80 0000 (£64,846),

b. the exempted contract (or contracts) worth up to 20% of the lots’ total value.

Here it is important to note that the EU procurement rules state clearly that the subdivision of contracts to lots should not be done with the intention of avoiding the application of the public procurement rules (See Article 9 (3) of Directive 2004/18/EC and Reg. 8 (19) Public Contracts Regulations 2006). This should be stated clearly in the final report because otherwise unwanted messages may be sent both to contracting authorities and the European Commission.[1]

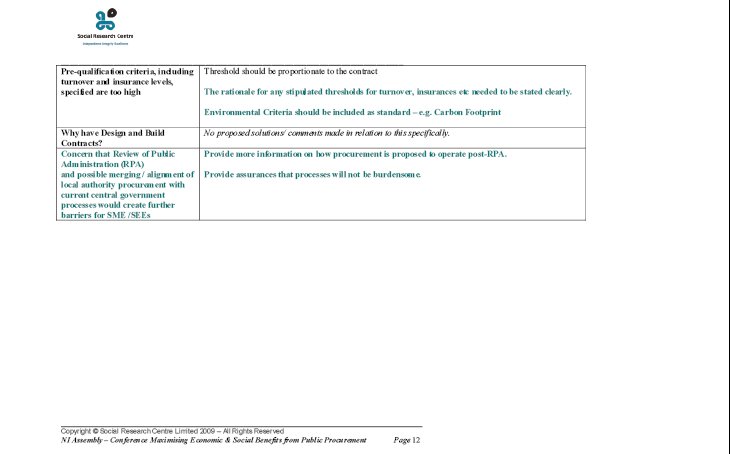

- The suggestion for a proportionate consideration of the required level for pre-selection criteria is very important. It should be remembered that these requirements are there in order to ensure a certain level of professionalism and reliability of the providers. In fact according to the principle of proportionality contracting authorities are required to set these pre-qualification requirements at levels that are not higher than necessary (i.e they should not be unduly burdensome) for guaranteeing the reliability of the providers. This is also proposed in the European Commission’s Code of best practices for facilitating SMEs access in public procurement contracts.[2]

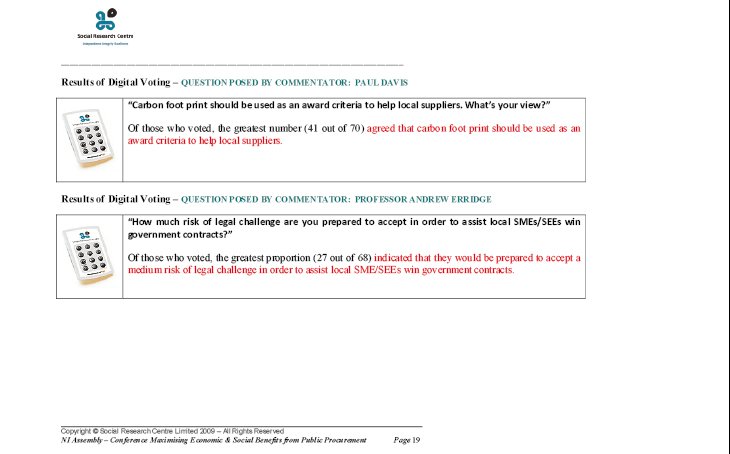

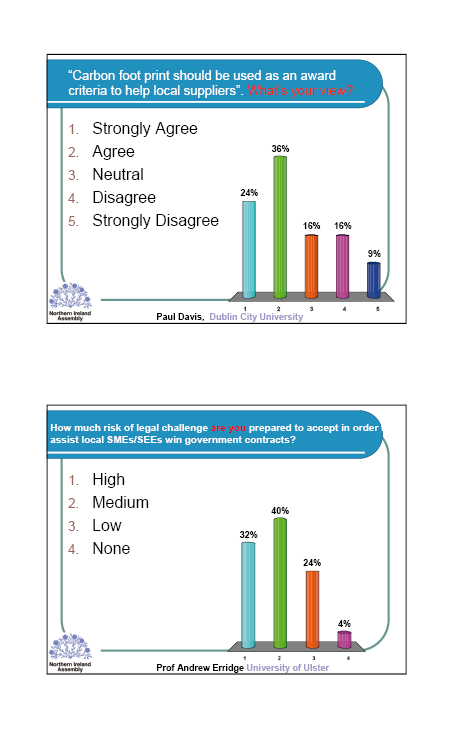

- With regard to the inclusion of environmental criteria such as “carbon “footprint" it can be said that under the current procurement rules this is allowed.

- The suggestion for further examination of the full supply chain in order to ascertain whether SMEs and SEEs are involved in the delivery of public procurement contracts as subcontractors requires further clarification. It is not clear to the author whether this refers to:

a) a proposal for the competent departments of the Northern Ireland Executive to conduct an ex post examination (by a means of a study perhaps) in order to ascertain the general level of involvement of SMEs and SEEs as subcontractors in public procurement carried out by contracting authorities in Northern Ireland; or

b) a suggestion for including in the screening/evaluation process of specific procurement contracts (for instance as award sub-criterion or a condition of performance of the contract) the involvement of SMEs and/or SEEs as subcontractors.

It can be said that there is nothing in the procurement rules to prevent (a). In fact this seems an excellent idea. With regard to (b) however it is important remember the following:

First of all contract award sub-criteria have to be linked with the subject matter of the contract and they should observe the principle of equal treatment. Thus if such an award criterion of contract condition is imposed it should take into account the involvement of all SMEs and/or SEEs irrespective of their nationality.

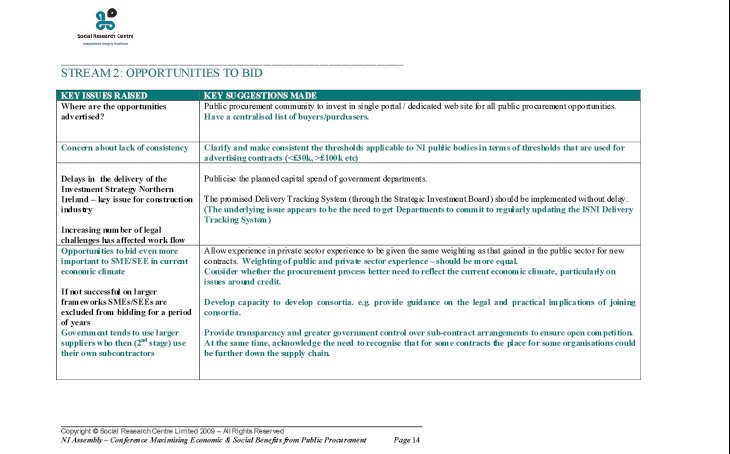

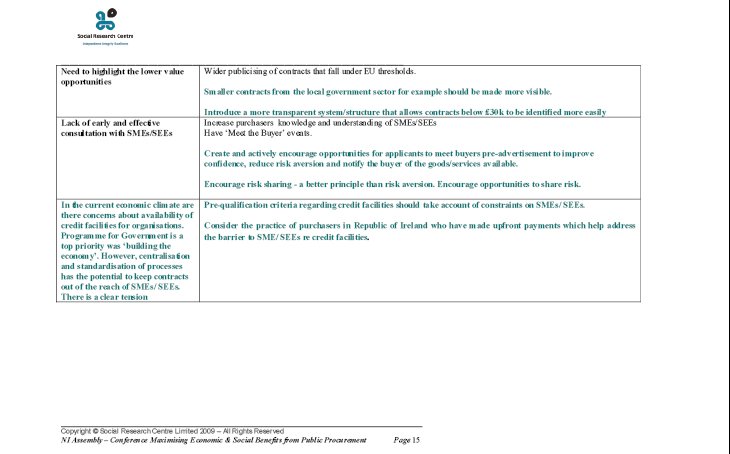

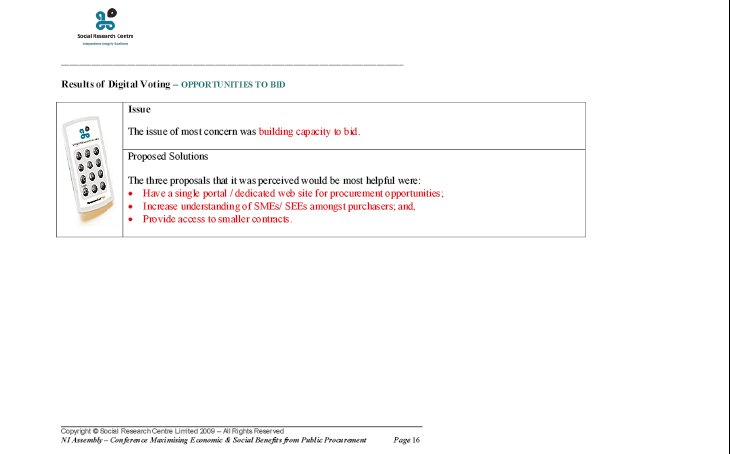

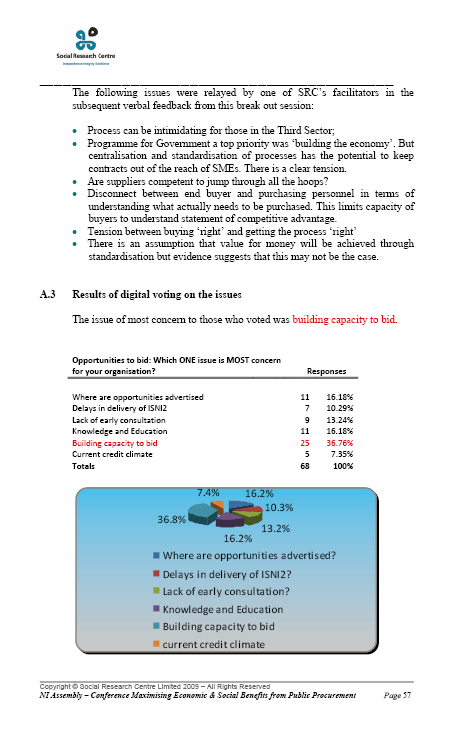

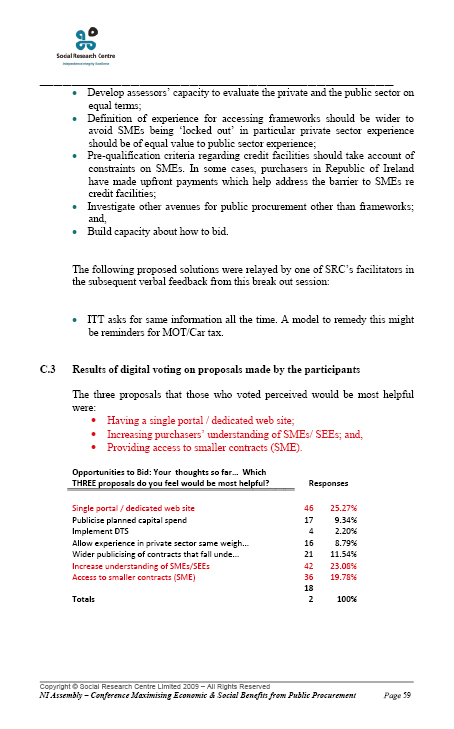

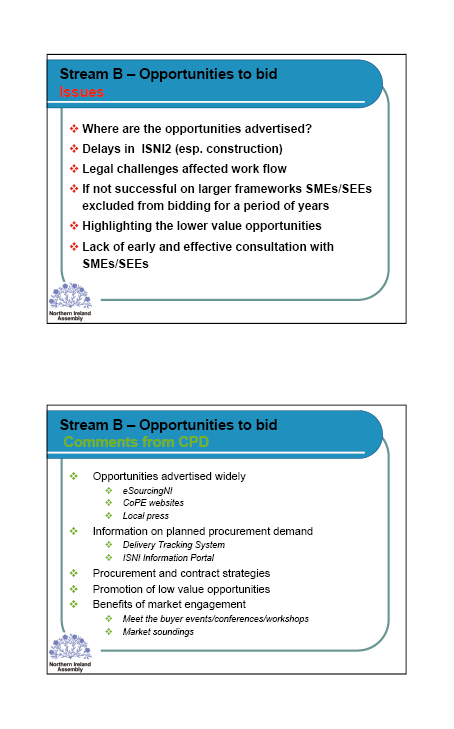

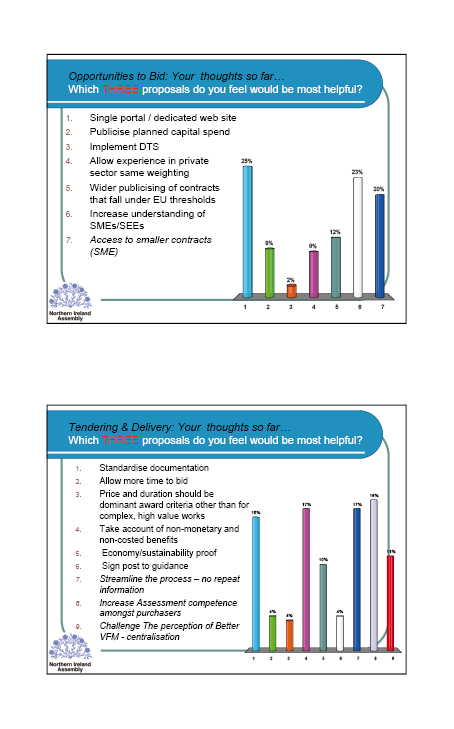

B. Stream 2: Opportunities to Bid

- The issue of “below threshold" contracts is of fundamental importance for SMEs because these contracts fit nicely with the capabilities of smaller SMEs and start-ups. The advantage of the “below threshold" contracts is that because of their smaller value they do not necessarily attract the interest of foreign competitors. For this reason an improved mechanism of dissemination of “below threshold" contract opportunities (the proposal for a single portal is very positive) would be beneficial for SMEs. It is important to note at this point nevertheless that despite the fact that these contracts do not fall within the field of application of the public procurement directive and the national implementing regulations, contracting authorities may be still subject to certain obligations (including minimum publicity obligations, equal treatment) that arise directly from the EC Treaty (See the European Court of Justice case law[3] in this regard).

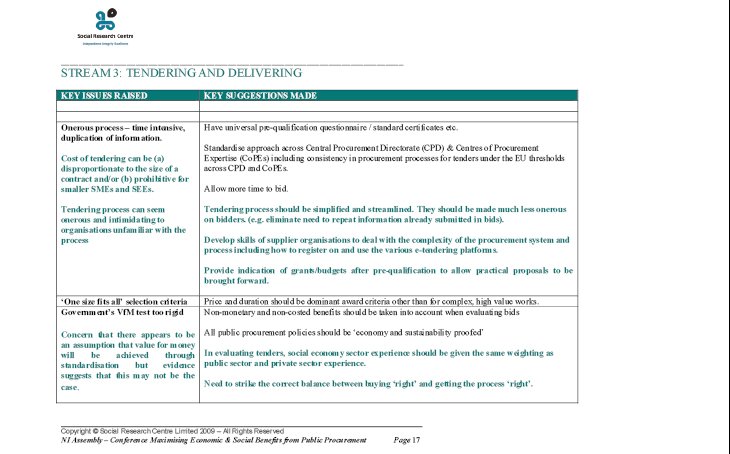

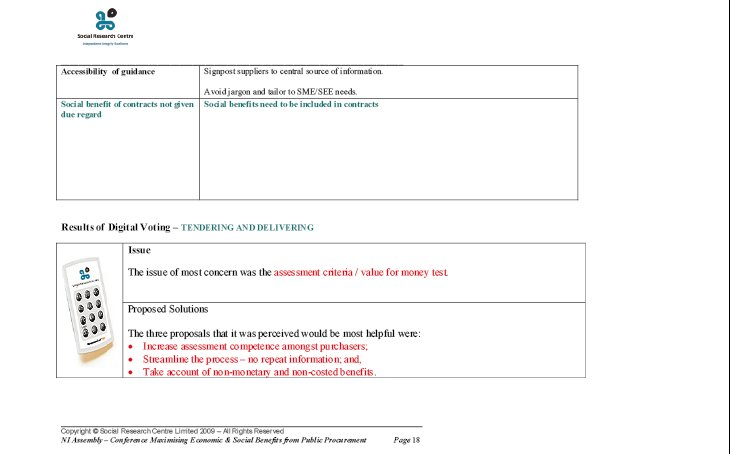

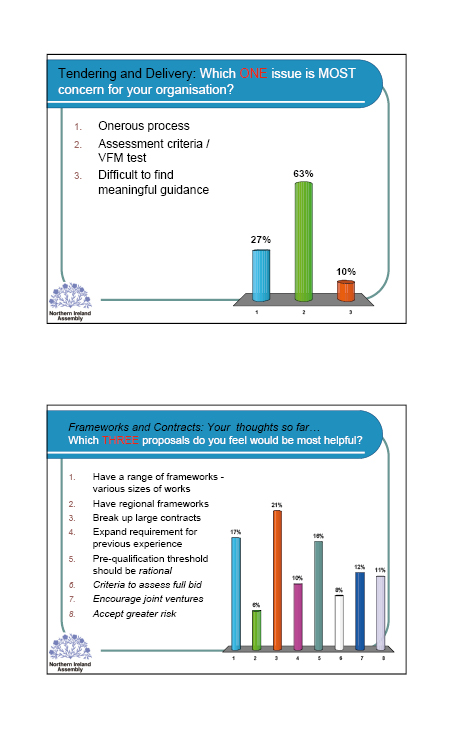

C. Stream 3: Tendering and Delivering

- Regarding the criticism of the value for money test it should be remembered that this is meant to bring some flexibility by allowing contracting authorities to consider other important factors apart from price in the award of procurement contracts. It is also true that contracts that are not too complex could be awarded on the basis of the lowest price alone. Nevertheless it seems that the European Legislator left the decision for the appropriate award criterion (for contracts above the applicable thresholds) namely the “lowest price" or the “most economically advantageous tender" to each contracting authority. Thus a national provision that limits this choice of contracting authorities by establishing a “blanket" application of price as the only available award criterion for certain kinds of contracts could raise questions of compatibility with the European public procurement rules. Nevertheless contracting authorities could be encouraged to adopt the “lowest price" as award criterion for contracts that are not too complex. Lastly it is important to note that when contracting authorities use the “most economically advantageous tender" as the award criterion they should be stipulate clearly and in advance all the relevant sub-criteria/factors and their relative value.

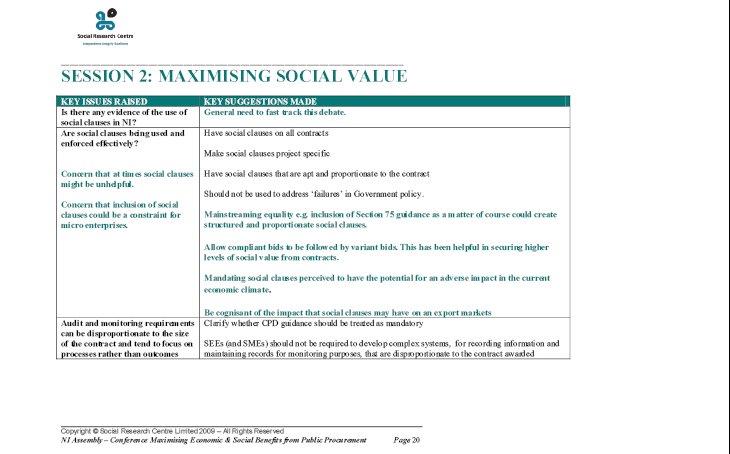

- With regard to taking into account non-monetary benefits it should be mentioned that the procurement rules allow for the use of “social" and “environmental" considerations as award sub-criteria under the proviso that these relate to the subject matter of the contract. More importantly, especially with regard to social criteria/considerations, any national measures or practices must not be discriminatory. This is the settled case law of the European Court of Justice.[4] Even for public procurement contracts that are not covered by the European public procurement rules (for example below threshold contracts and service concessions contracts) national rules cannot introduce discriminatory measures unless they are justified by one of the available grounds mentioned in the Treaty (for example see grounds mentioned in Article 30 EC) and they are proportionate (achieve their aim -for example protection of the life of humans- in the least intrusive manner for the internal market.[5] With regard to national measures that are equally applicable on domestic and foreign suppliers but are de facto discriminatory the ECJ has ruled that such measures could be justified –apart from relying on specific grounds stipulated in the Treaty- if they try to achieve legitimate aims of general interest. Nevertheless the ECJ also ruled that these aims of general interest cannot be economic in nature. The question that arises in our case is whether the promotion of SMEs is an aim of general interest that is economic in nature. A strict reading of the case law of the European Court of Justice would reach this conclusion. Nevertheless this narrow approach has been criticized in the literature[6] and it could be argued that is outdated. However even if a more progressive interpretation that acknowledges the beneficial social impact that can stem from the support of SMEs –especially in the current economic climate- is accepted, any national measures trying to support SMEs through procurement would still have to pass the proportionality test.

[1] The bullet points in the section “key suggestions made" that stipulate: a)“Breaking into lots should be seen as the first recourse of any procurement tender" and b)“Break up large contracts into smaller contracts which would be more appropriate for local SMEs" may be misread by contracting authorities as an invitation to devise ways to evade the application of public procurement rules. A reminder or a clarification of the limits of this option (for example with the inclusion of the phrase “as far as permitted under the public procurement legislation") would be helpful.

[2] “European Code of Best Practices Facilitating Access by SMEs to Public Procurement Contracts", Commission Staff Working Document, SEC (2008) 2193 available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/publicprocurement/docs/sme_code_of_best_practices_en.pdf

[3] Case C-324/98, Telaustria Verlags GmbH and Telefonadress GmbH v Telekom Austria and Herold Business Data AG, [2000] ECR I-10745. However see also Case C-231/03 Coname [2005] ECR I-7287, where the ECJ stated as obiter dictum that an obligation to advertise may not apply to a contract of modest economic value that would not give rise to cross-border interest; see also the Opinion of Advocate General Sharpston of 18 January 2007, in Case C-195/04, Commission v Finland [2007] ECR I-3351 where the Advocate General argued that in the case of “below-threshold" contracts Member States have discretion to determine what the sufficient degree of transparency should be.

[4] See for example Case 31/87, Gebroeders Beentjes v Netherlands [1988] ECR 4635 and Case

C-225/98, Commission v French Republic, [2000] ECR I-7445.

[5] See in this regard Case C–360/89, Commission v Italy [1992] ECR I-3401 and C-21/88, Du Pont de Nemours Italiana SpA v Unita Sanitaria Locale No.2 Di Carrara [1990] ECR I-889

[6] S. Arrowsmith, “Application of the EC Treaty and Directives to Horizontal Policies: a Critical Review", chapter 4 (pp.147-248) in Arrowsmith and Kunzlik (eds), Social and Environmental Policies in EC Procurement Law: New Directives and New Directions (2009; CUP)