| Membership | What's Happening | Committees | Publications | Assembly Commission | General Info | Job Opportunities | Help |

AD HOC COMMITTEE Report on Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 Ordered by

The Ad Hoc Committee to

be printed 10 June 2002 REPORT AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE AD HOC COMMITTEE The Committee was established, in accordance with Assembly Standing Order 49(7), by resolution of the Assembly on Tuesday 21 May 2002. The function of the Committee is to consider the proposal for a Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 referred by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and to report thereon to the Assembly by Tuesday 2 July 2002. The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5. The membership of the Committee is as follows:-

The Report and Proceedings of the Committee are published by the Stationery Office by order of the Committee. All publications of the Committee are posted on the Assembly's website as http://www.ni-assembly.gov.uk/ All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of Ad hoc Committee, Room 371, Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast BT4 3XX. CONTENTS Background to the Report Introduction Remit of the Committee Proceedings of the Committee Background to Access to Justice in Northern Ireland Review of Legal Aid in Northern Ireland Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 Committee's consideration of the proposed draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 12 General Comments Establishment of the Legal Service Commission Provision of Civil Legal Services Provision of Criminal Legal Services Quality Standards Other Funding of Legal Services Appendices Appendix 1 - Minutes of Proceedings Appendix 2 - List of Witnesses Appendix 3 - Minutes of Evidence Appendix 4 - Written Submissions to the Committee BACKGROUND TO THE REPORT INTRODUCTION 1. This is a Report made by the Ad hoc Committee to the Assembly, pursuant to the resolution of the Assembly on Tuesday, 21 May 2002. The Report describes the work of the Committee over the period 6 June to 24 June 2002. REMIT OF THE COMMITTEE 2. As agreed by the Assembly, the Committee had the following function: To consider the proposal for a draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 referred by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and to report thereon to the Assembly by Tuesday, 2 July 2002 . 3. A copy of the above paper is available from the Northern Ireland Office's website at http://www.nio.gov.uk/ PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE 4. During the period covered by this Report, the Committee held five meetings: 6, 11,13, 17 and 24 June 2002. The Minutes of Proceedings for these meetings are included at Appendix 1. 5. In the course of its proceedings, the Committee heard evidence from the following bodies -

6. At its meeting on 11 June 2002 the Committee received evidence from the Director of Legal Aid from the Lord Chancellor's Department on the proposal for a Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Director of Legal Aid was accompanied by the Business Manager, Order in Council Implementation Team. The Lord Chancellor's Department made a written submission to the Committee in advance of their attendance. 7. At its meeting on 13 June 2002 the Committee received evidence from the Chief Executive of the Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux and the Chief Commissioner of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. The Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission outlined their view of the proposed Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission made written submissions to the Committee in advance of their attendance. 8. At its meeting on 17 June 2002 the Committee received evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. The Law Society of Northern Ireland and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland outlined their view of the proposed Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Law Society of Northern Ireland and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland made written submissions to the Committee in advance of their attendance. 9. The Minutes of Evidence for these meetings are included at Appendix 3. BACKGROUND TO ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND REVIEW OF LEGAL AID IN NORTHRN IRELAND 10. On 19 February 1998 the Government announced a review into the provision and administration of legal aid in Northern Ireland. The announcement indicated that officials would: (a) undertake a review into arrangements for the administration and provision of legal aid in Northern Ireland, bringing forward recommendations for change where necessary; (b) consider, in the Northern Ireland context, the proposed reforms to legal aid in England and Wales. 11. As a result of this review a Consultation Paper, "Public Benefit and the Public Purse" was published on 14 June 1999. Publication of the Consultation Paper marked the commencement of the first substantive public discussion on legal aid for many years. The Consultation Paper set out the Government's objectives for and commitment to the modernisation of legal aid in Northern Ireland. The objectives set by Government in the Consultation Paper are summarised as follows: (a) ensuring appropriate funding arrangements are in place to secure access to the most appropriate means to resolve legal issues for citizens; (b) targeting resources to those in greatest need; (c) ensuring that the overall cost of legal services is affordable and controllable; (d) securing value for money from quality legal services; and (e) establishing the most effective and efficient administrative structure to deliver legal services. 12. The key proposals set out in the Consultation Paper were: (a) establishing a new Administrative Body (the Legal Services Commission); (b) establishing capped budgets for legal services (other than in criminal matters); (c) securing the services of quality providers at best value for money prices; and (d) ensuring that the most appropriate and cost effective solutions are available to the public. 13. Following consultation the Government published a Decisions Paper "The Way Ahead" [CM 4849] in September 2000. The Government stated that the approach set out in the Decisions Paper would provide a modern, transparent and accountable administrative structure to deliver quality assured legal services to all the people of Northern Ireland. 14. The Decisions Paper indicates that, within the context of the reform programme, the Government is determined to take effective control of the levels of public funding allocated to the provision of legal services, and to ensure that the funds available are targeted on meeting the real needs of the most vulnerable in society. 15. The third strand of the approach outlined in the Decisions Paper was the development of mechanisms to ensure that the taxpayer can be assured that the money spent on legal services is spent on a high quality service. ACCESS TO JUSTICE (NORTHERN IRELAND) ORDER 2002 16. The current statutory basis for the provision and administration of legal aid is set out in the Legal Aid, Advice and Assistance (Northern Ireland) Order 1981 [SI 1981/228 (NI 8)] ("the 1981 Order"). 17. The Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 (the "proposed Order") provides a modern basis for the provision and administration of legal services. Part I Citation, Commencement and Interpretation 18. This sets out the title of the Order as the Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. Part II Northern Ireland Legal Services Commission 19. Provides for the setting up of the Northern Ireland Legal Services Commission (referred to as "the Commission"). The Commission shall exercise its functions for the purpose of - (a) securing (within the resources made available, and priorities set, in accordance with this Part) that individuals have access to civil legal services that effectively meet their needs, and of promoting the availability to individuals for such services, and (b) securing that individuals involved in criminal investigations or relevant proceedings have access to such criminal defence services as the interests of justice require. Membership of the Commission 20. The Commission shall consist of - (a) a member who is to chair it, and (b) not fewer than six, nor more than ten, other members. 21. In appointing persons to be members of the Commission the Lord Chancellor shall have regard to the desirability of securing that the Commission includes members who (between them) have experience in or knowledge of - (a) the provision of services which the Commission can fund as civil legal services or criminal defence services; (b) the work of the courts; (c) consumer affairs; (d) social conditions; and (e) management. Power to replace Commission with two bodies 22. Provides that the Lord Chancellor may by order establish in place of the Commission two bodies - (a) one to have functions relating to civil legal services, and (b) the other to have functions relating to criminal defence services. Planning 23. Provides for the Commission to - (a) inform itself about the need for and the provision of civil legal services and criminal defence services and the quality of the services provided; (b) plan towards meeting the need by the performance by the Commission of its functions; (c) co-operate with such authorities and other bodies and persons as it considers appropriate in facilitating the planning of what can be done by them to meet that need by the use of any resources available to them; (d) notify the Lord Chancellor of what it has done under this Article. Powers of Commission 24. In particular, the Commission shall have power - (a) to enter into any contract; (b) to make grants (with or without conditions); (c) to make loans; (d) to invest money; (e) to promote or assist in the promotion of publicity relating to its functions; (f) to undertake any inquiry or investigation which it may consider appropriate in relation to the discharge of any of its functions, and (g) to give to the Lord Chancellor any advice which it may consider appropriate in relation to matters concerning any of its functions. Guidance 25. The Lord Chancellor may give guidance to the Commission as to the manner in which he considers it should discharge its functions and the Commission shall take into account any such guidance. Northern Ireland law and foreign law 26. The Commission may not fund civil legal or criminal defence services relating to any law other than that of Northern Ireland, unless any such law is relevant for determining any issue relating to the law of Northern Ireland. Civil Legal Services 27. For the purposes of this Order "civil legal services" means advice, assistance and representation, other than advice, assistance or representation which the Commission is required to fund as criminal defence services. Funding of Services 28. The Commission shall establish and maintain a fund from which it shall fund civil legal services. The Lord Chancellor - (a) shall pay to the Commission the sums which he determine are appropriate for the funding of civil legal services by the Commission, and (b) may determine the manner in which and times at which the sums are to be paid to the Commission and may impose conditions on the payment of the sums. Services which may be funded 29. The Commission shall set priorities in its funding of civil legal services, and the priorities shall be set - (a) in accordance with any directions given by the Lord Chancellor, and (b) after taking into account the need for such services, 30. The Commission may fund civil legal services by - (a) entering into contracts with persons or bodies for the provision of services by them; (b) making payments to persons or bodies in respect of the provision of services by them; (c) making grants or loans to persons or bodies to enable them to provide, or facilitate the provision of services; (d) establishing and maintaining bodies to provide, or facilitate the provision of services; (e) making grants or loans to individuals to enable them to obtain services; (f) itself providing services; or (g) doing anything else which it considers appropriate for funding services. Individuals for whom services may be funded 31. The Commission may only fund civil legal services for an individual if his financial resources are such that, under regulations, he is an individual for whom they may be so funded. Decisions about provision of funded services 32. The services which the Commission may fund as civil legal services are those which the Commission considers appropriate (subject to Article 12(5) and the priorities set under Article 12(1). Funding Code 33. The Commission shall prepare a code setting out the criteria according to which any decision is to be taken as to - (a) whether to fund (or continue to fund) civil legal services for an individual for whom they may be so funded; and (b) if so, what services are to be funded for him. Procedure relating to funding code 34. This section outlines the procedure to be carried out after preparation of the code or a revised version of the code. Terms of provision of funded services 35. An individual for whom civil legal services are funded by the Commission shall not be required to make any payment in respect of the services except where regulations otherwise provide. Costs orders against assisted parties and costs of successful unassisted parties 36. The Commission makes provision for costs orders against assisted parties and the awarding of costs of successful unassisted parties. Regulations about costs in funded cases 37. Subject to Articles 18 and 19, regulations may make provision about costs in relation to proceedings in relation to which, or to a part of which, civil legal services are funded for any of the parties by the Commission. Criminal defence services 38. The Commission shall establish and maintain a fund from which it shall fund - (a) advice and assistance in accordance with Article 23, and (b) representation in accordance with Articles 24 and 30. Criminal defence services: codes of conduct 39. The Commission shall prepare a code of conduct to be observed by employees of the Commission, and employees of any body established and maintained by the Commission, in the provision of criminal defence services. 40. The code shall include - (a) duties imposed in accordance with any scheme made by the Commission under section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998(b); (b) duties to protect the interests of the individuals for whom criminal defence services are provided; (c) duties to the court; (d) duties to avoid conflicts of interest; and (e) duties of confidentiality; (f) and duties on employees who are members of a professional body to comply with the rules of the body. 41. The Commission may from time to time prepare a revised version of the code. 42. Before preparing or revising the code the Commission shall consult the Law Society and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland and such other bodies or persons as it considers appropriate. 43. After preparing the code or a revised version of the code the Commission shall send a copy to the Lord Chancellor. 44. If he approves it he shall lay it before each House of Parliament. 45. The Commission shall publish - (a) the code as first approved by the Lord Chancellor, and (b) where he approves a revised version, either the revisions or the revised code as appropriate. 46. The code, and any revised version of the code, shall not come into force until it has been approved by a resolution of each House of Parliament. Advice and Assistance 47. The Commission shall fund such advice and assistance as it considers appropriate. Representation 48. The Commission shall fund representation to which an individual has been granted a right in accordance with Article 26 or 27. Individuals to whom right to representation may be granted 49. This sets out the circumstances in which the right to representation may be granted. Grant of right to representation by court 50. A court before which any relevant proceedings take place, or are to take place, has power to grant a right to representation in respect of those proceedings except in such circumstances as may be prescribed. Grant of right to representation by Commission 51. The Commission shall have power to grant rights to representation in respect of any one or more of the descriptions of proceedings prescribed under Article 2(4)(g), and to withdraw any rights to representation granted by it. Appeals 52. Except where regulations otherwise provide, an appeal shall lie to such court or other person or body as may be prescribed against a decision - (a) to refuse a right to representation in respect of relevant proceedings; (b) to impose or vary a limitation on such a right; (c) not to extend such a right; or (d) to withdraw such a right. Criteria for grant of right to representation 53. Any question as to whether a right to representation should be granted or extended, or whether a limitation on representation should be imposed, varied or removed, shall be determined according to the interests of justice. Selection of representative 54. An individual who has been granted a right to representation in accordance with Article 26 or 27 may, in accordance with any determination of the Commission under paragraph (2) and subject to Article 36, select any representative or representatives willing to act for him; and, where he does, the Commission is to comply with the duty imposed by Article 24 by funding representation by the selected representative or representatives. Extent of right to representation; review and appeal 55. Regulations shall make provision for the review, in prescribed circumstances, of determinations by the Commission under Article 30(2). Terms of provision of funded services 56. (1) An individual for whom criminal defence services are funded by the Commission shall not be required to make any payment in respect of the services except where paragraph (2) applies. (2) Where representation for an individual in respect of relevant proceedings in any court is funded by the Committee under Article 24, the court may, subject to regulations under paragraph (3), make an order requiring him to pay some or all of the cost of any representation so funded for him (in proceedings in that or any other court). Restriction of disclosure of information 57. Information which is furnished to the Commission or any court, tribunal or other person or body on whom functions are imposed or conferred by or under this Part and in connection with the case of an individual seeking or receiving civil legal services or criminal defence services funded by the Commission shall not be disclosed except as permitted by regulations. Misrepresentation etc. 58. Any person who intentionally fails to comply with any requirement imposed by virtue of this Part as to the information to be furnished, or in furnishing information required by virtue of this Part makes any statement or representation which he knows or believes to be false, shall be guilty of an offence. Position of service providers and other parties etc. 59. Except as expressly provided by regulations, the fact that civil legal services or criminal defence services provided for an individual are or could be funded by the Commission, shall not affect - (a) the relationship between that individual and the person by whom they are provided or any privilege arising out of that relationship; or (b) any right which that individual may have to be indemnified, in respect of expenses incurred by him, by any other person. Solicitors and barristers 60. The Commission shall not fund any civil legal services or criminal defence services provided by a solicitor who is for the time being prohibited from providing such services by an order under Article 51B(1) or (3) of the Solicitors (Northern Ireland) Order 1976(a). 61. The Commission shall not fund any civil legal services or criminal defence services provided by a barrister if it determines that, arising out of his conduct when providing or selected to provide such services or his professional conduct generally, there is good reason for refusing, temporarily or permanently, to fund such services provided by him. Register of persons providing services 62. Regulations may make provision for the registration by the Commission of persons who are eligible to provide civil legal services or criminal defence services funded by the Commission. Part III Other funding of legal services 63. Interpretation of Part III "Advocacy services" means any services which it would be reasonable to expect a person who is exercising, or contemplating exercising, a right of audience in relation to any proceedings, or contemplated proceedings, to provide; "litigation services" means any services which it would be reasonable to expect a person who is exercising, or contemplating exercising, a right to conduct litigation in relation to any proceedings, or contemplated proceedings, to provide; "proceedings" includes any sort of proceedings for resolving disputes (and not just proceedings in a court), whether commenced or contemplated; "a right of audience" means the right to appear before and address a court including the right to call and examine witnesses; "a right to conduct litigation" means the right - (a) to issue proceedings before any court; and (b) to perform any ancillary functions in relation to proceedings (such as entering appearances to actions). Conditional fee agreements 64. A conditional fee agreement which satisfies all of the conditions applicable to it by virtue of this Article shall not be unenforceable by reason only of its being a conditional fee agreement; but (subject to paragraph (5)) any other conditional fee agreement shall be unenforceable. Conditional fee agreements: supplementary 65. The proceedings which cannot be the subject of an enforceable conditional fee agreement are criminal proceedings and family proceedings. Litigation Funding Agreements 66. A litigation funding agreement which satisfies all of the conditions applicable to it by virtue of this Article shall not be unenforceable by reason only of its being a litigation funding agreement. Litigation funding agreements: costs 67. A costs order made in any proceedings may, subject in the case of court proceedings to rules of court, include provision requiring the payment of any amount payable under a litigation funding agreement. Recovery of insurance premiums by way of costs 68. Where in any proceedings a costs order is made in favour of any party who has taken out an insurance policy against the risk of incurring a liability in those proceedings, the costs payable to him may, subject in the case of court proceedings to rules of court, include costs in respect of the premium of the policy. Recovery where body undertakes to meet cost liabilities 69. This Article applies where a body of a prescribed description undertakes to meet (in accordance with arrangements satisfying prescribed conditions) liabilities which members of the body or other persons who are parties to proceedings may incur to pay the costs of other parties to the proceedings. Part IV Application to Crown 70. This Order shall bind the Crown to the full extent authorised or permitted by the constitutional laws of Northern Ireland. Orders, regulations and directions 71. Any direction given by the Lord Chancellor to the Commission under Part II may be varied or revoked. Remuneration Orders 72. The Lord Chancellor is empowered to make remuneration orders, setting out a range of fees or mechanisms for calculating fees, which the Commission will implement and observe when funding both criminal and civil services. Remuneration orders could for example set:

73. In making a remuneration order, the Lord Chancellor must have regard 'among the matters which are relevant, to- (a) the time and skill which the provision of services of the description to which the order relates requires; (b) the number and general level of competence of persons providing those services; (c) the cost to public funds of any provision made by the regulations; and (d) the need to secure value for money.' 74. The Lord Chancellor is not required to consider other factors - such as existing remuneration levels or market rates. Transitional provisions and savings 75. The Lord Chancellor may by order make such transitional provisions and savings as he considers appropriate in connection with the coming into operation of any provision of this Order. Minor and consequential amendments and repeals 76. The statutory provisions specified in Schedule 4 shall be amended as specified in that Schedule. 77. The statutory provisions specified in Schedule 5 are hereby repealed to the extent specified in column 3 of that Schedule. COMMITTEE'S CONSIDERATION OF THE PROPOSED DRAFT ACCESS TO JUSTICE (NORTHERN IRELAND) ORDER 2002 78. During the Committee's deliberations on the proposals for reform of the legal aid system in Northern Ireland, members considered a wide variety of issues. The comments of the Committee are set out below under the following headings:-

GENERAL COMMENTS 79. The Committee welcomed the opportunity to consider the proposals for reform of the legal aid system in Northern Ireland and recognised those proposals as being of major significance for many years ahead. Given the importance of these proposals, the Committee considered that a full, proper and meaningful consultation would be of vital importance, as the proposals were going to have an impact on the future of legal aid provision. 80. The Committee expressed concern about the period of time allocated to consider the Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002, although this was within the sixty days allowed within Section 85 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. Due to the wide ranging and complex areas for consideration the Committee was of the opinion that there is a need for on-going scrutiny of both the draft Order and any subsequent implementation plan.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE LEGAL SERVICE COMMISSION 81. The Committee considered issues surrounding the establishment of the new Legal Services Commission. The new Legal Services Commission will be responsible for the administration of the public funding of legal services; making new provision for the public funding of civil legal services; making new provision for the public funding of criminal legal services; providing for the registration of those seeking to provide publicly funded legal services; and making provision for alternative methods of paying for legal services, i.e. conditional fee arrangements and litigation fund agreements. 82. The Committee agreed with the principle of establishing an impartial Legal Services Commission which removes the administration of legal aid from the Law Society, a body whose members benefit from the current provision of legal aid. 83. In scrutinising the legislation the Committee formed the view that many of the proposed major areas were seen as contingent legislation i.e. to provide for 'fall back' positions in the event that the proposals do not go according to plan. The Committee had serious reservations about this procedure. The proposal to allow for the Legal Services Commission to implement much of the detail, without many of the areas being clearly defined on the face of the legislation, is a cause for concern. 84. However, the Committee noted evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland where they stated "we do have considerable reservations as to whether another Commission of this type or size is necessary or appropriate for the administration of legal aid in Northern Ireland." The Committee expressed concern over the lack of detail on the projected setting up and running costs for the Legal Services Commission.

PROVISION OF CIVIL LEGAL SERVICES 85. Under existing legislation, the Law Society administers legal aid so as to provide advice, assistance and representation to parties in certain civil proceedings, subject to a merits test, and in some cases a means test. 86. Civil legal aid is at present available under three schemes. The Lord Chancellor's Department has described them and the means test as follows: 'Legal Advice and Assistance (Green Form Scheme) Legal advice and assistance, otherwise known as the Green Form Scheme, is intended to cover preliminary advice and assistance from a solicitor including advice, writing letters, entering into negotiations, obtaining an opinion and the preparation of a tribunal case. To qualify for this advice a question of Northern Ireland law must be involved. Advice and assistance stops short of representation in court and it cannot be obtained when a civil aid certificate has been issued in connection with the matter. Responsibility for making the financial assessment of eligibility for Green Form advice falls to the solicitor providing the advice. ABWOR Assistance by way of representation (ABWOR) covers the preparation and presentation of civil cases in the Magistrates' Court. These cases include separation, maintenance and paternity proceedings and certain work in respect of children. It is also available to patients who appear before Mental Health Review Tribunals. A solicitor requires approval from the Legal Aid Department or the court before assistance under ABWOR can be given. Civil Legal Aid The granting of civil legal aid is a matter for the Law Society through the Legal Aid Committee and the Legal Aid Department and is subject to certain statutory criteria. Civil legal aid is available for cases in: (a) the House of Lords in the exercise of its jurisdiction in relation to any appeal from Northern Ireland; (b) the High Court and the Court of Appeal; (c) any county court; (d) the magistrates' court (for cases about marriage and the family, and also in certain circumstances for cases concerning debt); (e) Lands Tribunal; and (f) the Enforcement of Judgements Office.' 87. The draft Order proposes to deliver civil legal services through advice, assistance and representation. Accordingly, the Legal Services Commission will establish and maintain a new fund to provide civil legal services. The Lord Chancellor will pay such sums into the fund as he may determine and may impose conditions upon those payments. The fund will be capped. 88. The Legal Services Commission will prepare a Funding Code which will set out the criteria for determining whether civil legal services should be provided in a particular case. The Code will also set out the procedures for making applications for funding. The factors which the Legal Services Commission must consider when preparing the Code are: '(a) the likely cost of funding the services and the benefit which may be obtained by their being provided, (b) the availability of sums in the fund established under Article 11(1) for funding civil legal services and (having regard to present and likely future demands on that fund) the appropriateness of applying them to fund the services, (c) the importance of the matters in relation to which the services would be provided for the individual, (d) the availability to the individual of services not funded by the Commission and the likelihood of his being able to avail himself of them, (e) if the services are sought by the individual in relation to a dispute, the prospects of his success in the dispute, (f) the conduct of the individual in connection with civil legal services funded by the Commission (or an application for funding) or in, or in connection with, any proceedings, (g) the public interest, and (h) such other factors as the Lord Chancellor may by order require the Commission to consider.' 89. The Committee raised concerns regarding the level at which the fund will be capped, how that level will be determined and what process will be used to review the cap. Indeed, in the evidence provided by the Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux (NIACAB), a strong case was made for the retention of ABWOR as an independent service. The Committee noted that, at present, legal aid is only payable in respect of time spent in preparing for a tribunal but not any representation at an actual tribunal. The statistical evidence set out in Appendix 4 displays the value of representation at tribunals. The Committee supported the extension of representation in actual Tribunals, it also noted the recent reforms in Scotland whereby Civil Legal Aid can be made available in some situations.

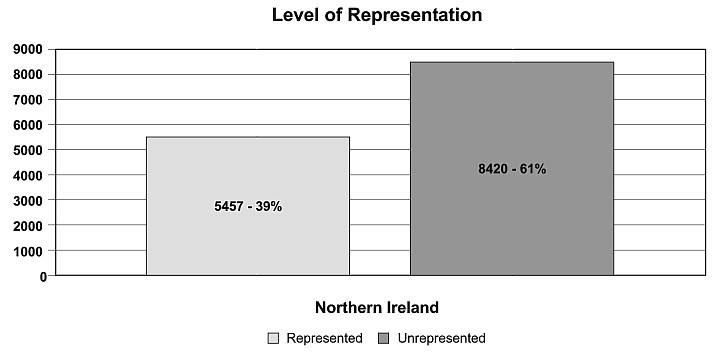

Current potential unmet need in the civil legal aid sector 90. The Committee took evidence from the NIACAB. The NIACAB currently deal with approximately 200,000 clients annually. However, they estimate the level of unmet need to be in the region of an additional 200,000 clients. The Committee agreed that any funding set aside by the Legal Services Commission will have to take account of the needs of the community and voluntary sector.

91. The Committee noted the concerns of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission which stated that "exclusion of election petitions from the range of available civil legal services would mean that important electoral rights (protected by Article 3 of Protocol 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights) could not be vindicated with the assistance of publicly-funded legal services." The Committee supported the view of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission.

Funding Code 92. The Legal Services Commission will prepare a Funding Code which will set out the criteria for determining whether civil legal services should be provided in a particular case. The Code will also set out the procedures for making applications for funding. The factors which the Legal Services Commission must consider when preparing the Code are: '(a) the likely cost of funding the services and the benefit which may be obtained by their being provided, (b) the availability of sums in the fund established under Article 11(1) for funding civil legal services and (having regard to present and likely future demands on that fund) the appropriateness of applying them to fund the services, (c) the importance of the matters in relation to which the services would be provided for the individual, (d) the availability to the individual of services not funded by the Commission and the likelihood of his being able to avail himself of them, (e) if the services are sought by the individual in relation to a dispute, the prospects of his success in the dispute, (f) the conduct of the individual in connection with civil legal services funded by the Commission (or an application for funding) or in, or in connection with, any proceedings, (g) the public interest, and (h) such other factors as the Lord Chancellor may by order require the Commission to consider.' 93. The Committee considered the proposed Funding Code and set of procedures which will apply to the code. The Committee, and a number of witnesses, expressed concern on the issue of the prioritisation of cases which will be covered by the fund. The Committee would welcome prior consultation on any proposals for prioritisation of clients in this area.

PROVISION OF CRIMINAL LEGAL SERVICES 94. Under current legislation, Criminal Legal Aid is available to individuals who:

subject to the applicant satisfying the court that he has insufficient means to fund his own defence and that it was in the interests of justice that he should receive legal aid. The draft Order proposes to replace this scheme. 95. Accordingly, the Legal Services Commission will establish and maintain a fund to provide criminal legal services. The Lord Chancellor will pay such sums into the fund as he may determine and to impose conditions upon those payments. Unlike the civil fund, the criminal fund will not be capped. 96. The Committee heard evidence from the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. In the evidence the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland stated that the level of representation for the client, should be determined by the Court, and not by the Commission. Only the Court can take an informed and objective view of the level of representation required by the issues, substance, seriousness and complexity of an individual case. 97. The Committee concurred with the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland's view that Article 30 of the draft Order is wholly restrictive of access to justice.

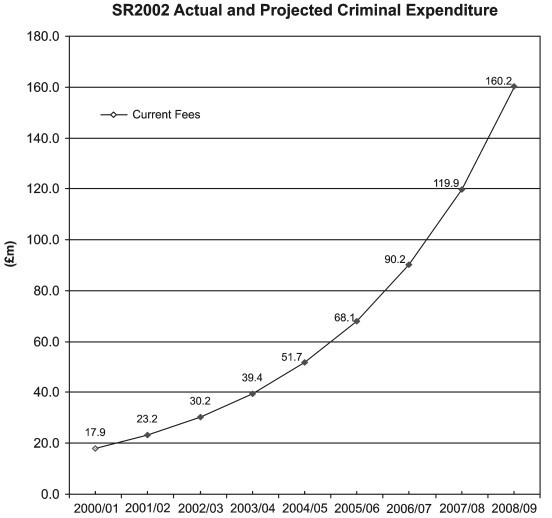

QUALITY STANDARDS Criminal Defence Service Code of Conduct 98. The Legal Services Commission is required to prepare a Criminal Defence Service Code of Conduct. It applies to employees of the Commission (such as salaried defenders), and employees of any body established and maintained by the Commission, in the provision of criminal defence services. 99. The Code is to be prepared or revised only on consultation with the Law Society and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland, and such other bodies or persons as the Legal Services Commission considers appropriate. It must be approved by both Houses of Parliament. Registration 100. The Lord Chancellor may, by regulation, establish a Registration Scheme and Code of Practice. Only firms and individuals that are registered, comply with the Code of Practice and satisfy quality mechanisms and monitoring will be entitled to provide publicly funded legal services. 101. The Committee noted evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland in which they stated "no-one would wish to argue with the proposition that legal services must be of consistently high quality." The Committee supports this view, however, it requested further detail on the standards of quality which will be imposed and how these standards will be informed both against firms and individuals.

OTHER FUNDING OF LEGAL SERVICES Additional Fee Arrangements 102. The draft Order proposes providing a statutory basis for Conditional Fee Agreements. Conditional Fee Agreements, also known as 'no-win-no fee' agreements, are intended to allow lawyers and clients to share both the risks and possible gains of litigation. They allow lawyers to 'undertake cases on the understanding that if a case is lost, the lawyer will not receive all or part of the usual fees or expenses. Where the agreement provides for enhanced fees, when the case is won, the lawyer is entitled to an uplift in addition to the usual fee. This is normally calculated as a percentage of his normal costs according to the level of risk. In this way the lawyer is rewarded for the risk taken in proceeding with a case for which he may not be paid. This definition covers recent developments in common law which recognise agreements to work for less than normal fees, but do not provide for enhanced fees... A case with a high chance of winning should attract a low enhanced fee. A case with a low chance of winning will attract a high enhanced fee.' 103. Accordingly, the draft Order provides that enforceable Conditional Fee Agreements can be entered into between lawyers and their clients. They cannot be employed in criminal or family proceedings. The Legal Services Commission would not be involved in Conditional Fee Agreements - it is an entirely private agreement between lawyer and client. 104. The Lord Chancellor, on consultation with the Law Society, the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland and others, may by regulation define the proceedings in which such fees are to be permitted and prescribe their maximum size. 105. The Committee considered evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. The General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland stated - "Conditional fees should not be introduced into Northern Ireland until such time has passed that would allow consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of their use in England and Wales and a study to be made to assess whether they are required in Northern Ireland." The Committee accepted the need for further research into Conditional Fee Arrangements (CFA).

Litigation Funding Arrangements 106. The draft Order also provides a statutory basis for Litigation Funding Agreements. A Litigation Funding Agreement is made between an individual and those representing a privately established fund - not with the lawyer taking the case, as occurs with Conditional Fee Agreements. As the Explanatory Document explains: 'litigation funding would allow litigants to pursue cases on the basis that they would not be liable for their legal costs if the case was unsuccessful....The fund would pay the lawyer in the normal way and in successful cases would be able to recover those costs by way of either a success fee from his opponent or a portion of the funded litigant's damages. (This is in contrast to Conditional Fee Agreements as under a litigation funding agreement the lawyer taking the case is remunerated irrespective of whether the case is successful.) The success fee or portion of damages would be paid into the fund to help meet the cost of lawyers' fees in unsuccessful cases. This Article also provides for a fee to be payable upon entering into a litigation funding agreement. Remuneration Orders 107. The Lord Chancellor is empowered to make Remuneration Orders, setting out a range of fees or mechanisms for calculating fees, which the Legal Services Commission will implement and observe when funding both criminal and civil services. Remuneration orders could for example set:

108. In making a Remuneration Order, the Lord Chancellor must have regard 'among the matters which are relevant, to- (a) the time and skill which the provision of services of the description to which the order relates requires; (b) the number and general level of competence of persons providing those services; (c) the cost to public funds of any provision made by the regulations; and (d) the need to secure value for money.' 109. The Committee considered a written submission from the Law Society of Northern Ireland in which it criticised the proposals for privately funded litigation arrangements. It has put forward proposals for a publicly funded Contingency Legal Aid Fund (CLAF) which could be administered on a not for profit basis. The Committee recognised that there may be some merit in this proposal and urged that it be given further consideration.

CONCLUSION 110. The Committee recognised that the reform of the legal aid system is both welcome and overdue. However, they adjudged that the provision of a short period for consultation, on the Draft Order in Council, in an important and complex area, is wholly inappropriate. The Committee noted that large sections of the Order are at best aspirational and at worst lacking in any degree of detail. The absence of a timebound implementation plan, with a heavy reliance on the proposed new Legal Services Commission for the delivery of many facets of the new system, caused the Committee a fair degree of concern. The Committee would welcome further extensive consultation, with all interested parties, before the laying of the Order in Council. APPENDIX 1 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS THURSDAY 6 JUNE 2002 Present: Mr Gregory Campbell MLA,

Chairperson Attendees: Mr Tony Logue, Committee Clerk Apologies: Mrs Eileen Bell MLA 2.52pm the meeting opened in private session-the Clerk in the Chair. 1. Apologies The apologies were noted. 2. Election of Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson The Clerk called for nominations for the position of Committee Chairperson. Mr Maginness proposed that: Mr Campbell be the Chairperson of this Committee. Mr Shipley Dalton seconded this and the nomination was accepted. On there being no further nominations the Clerk put the question without debate. Resolved, that Mr Campbell, being the only candidate proposed, be Chairperson of this Committee. 2.55pm Mr Campbell in the Chair. The Chairperson thanked members for their support and sought nominations for the position of Committee Deputy Chairperson. Professor McWilliams proposed that: Mr Maginness be the Deputy Chairperson of this Committee. Mr Shipley Dalton seconded this and the nomination was accepted. On there being no further nominations the Chairperson put the question without debate. Resolved, that Mr Maginness being the only candidate proposed, be Deputy Chairperson of this Committee. 3. Declaration of Interests Mr Shipley Dalton, Mr Maginness and Mr Weir declared that they were members of the Bar. 4. Procedures of the Committee The Chairperson referred members to a memorandum from the Committee Clerk on the procedures of the Committee contained in their briefing papers. Resolved, Witnesses-the Committee agreed to take evidence from relevant bodies as part of its proceedings. Voting-the Committee agreed that in the absence of consensus, simple majority would determine all decisions. Minutes of Evidence-the Committee agreed that in the event that any members are unable to attend an evidence session, the uncorrected Minutes of Evidence would be copied to those members for their information. Public meetings-the Committee agreed that it would hold all evidence sessions in public. Deputies-the Committee agreed to use deputies. Mr Weir deputised for Mr Paisley Jnr for the remainder of the meeting. 5. Forward Work Programme The Committee noted a memorandum from the Committee Clerk setting out a proposed forward work programme. The Committee agreed to invite the following bodies to give evidence- Lord Chancellor's Department; Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission: Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux; The Law Society of Northern Ireland; and The General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. It was further agreed that any further nominations to invite bodies to give evidence would be considered at the next meeting of the Committee and that a Press Release should be issued seeking written submissions to the Committee by any interested parties. Action: Clerk 6. Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 Members noted the contents of the draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 together with the Explanatory Memorandum, the Decisions Paper "The Way Ahead", the Consultation Paper "Public Benefit and the Public Purse", the Explanatory Document and a briefing paper from Northern Ireland Assembly Research and Library Services. Members conducted an initial analysis of the proposal for a draft Order in Council with assistance from the Northern Ireland Assembly Legal Advisor Service. Any other business No other matters were raised. 7. Date and time of next meeting The Committee agreed that it would next meet on Tuesday, 11 June 2002 at 10.30am in room 144 to hear evidence from the Northern Ireland Office and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. 3.16pm the Chairperson adjourned the meeting. Mr Gregory Campbell MLA 11 June, 2002 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS TUESDAY 11 JUNE 2002 Present: Ms Patricia Lewsley MLA,

Chairperson Attendees: Mr Tony Logue, Committee Clerk Apologies: Mr Gregory Campbell MLA 10.34am the meeting opened in private session-the Clerk in the Chair. 1. Co-option of Chairperson In the absence of the Chairperson, the Clerk called for nominations for the position of co-opted Chairperson. Mr Ervine proposed that : Ms Lewsley be the co-opted Chairperson for this meeting. Mr Weir seconded this and the nomination was accepted. On their being no further nominations the Clerk put the question without debate. Resolved, that Ms Lewsley, being the only candidate proposed, be the Chairperson of this Committee meeting. 10.36am Ms Lewsley in the Chair 2. Apologies The apologies were noted 3. Draft Minuts of Proceedings Resolved, that the draft Minuts of Proceedings for Thursday, 6 June be agreed. 4. Matters Arising There were no matters arising. 5. Evidence Session 10.38am The Chairperson called the Lord Chancellor's Department to be examined and the meeting continued in public session. Members heard evidence from the Lord Chancellor's Department on their role under the proposed new draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. Representing the Lord Chancellor's Department were -

11.41am Mr Ervine left the meeting 6. Any other business No other matters were raised. 7. Date and time of next meeting The Committee agreed that it would next meet on Thursday, 13 June 2002, when it would hear evidence from the Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. 11.45am the Chairperson adjourned the meeting. Ms Patricia Lewsley MLA 13 June, 2002 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS THURSDAY 13 JUNE 2002 Present: Mr Gregory Campbell MLA,

Chairperson Attendees: Mr Tony Logue, Committee Clerk 2.34pm the Chairperson opened the meeting in public session. 1. Apologies There were no apoligies. 2. Draft Minutes of Proceedings Resolved, That the draft Minuts of Proceedings for Tuesday, 11 be agreed. 3. Matters arising Members noted the contents of the Committee's Public Notice on the public consultation on the draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. 4. Evidence Session 2.35pm The Chairperson called the Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux to be examined.. Members heard evidence from the Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux on their role under the proposed new draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Northern Ireland Association of Citizen Advice Bureaux was represented by Mr Derek Alcorn, Chief Executive. 2.39pm Mrs Bell joined the meeting. 2.42pm Mr Paisley joined the meeting. 3.10pm Mr Maginness left the meeting. 3.12pm Mr McLaughlin left the meeting. On behalf of the Committee, the Chairperson welcomed Ms Tanya Monforte and Mr Shaun Stacey, Harvard Law School who sat in the public gallery to observe the proceedings of the Committee. 5. Evidence Session 3.12pm The Chairperson called the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission to be examined.. Members heard evidence from the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission on their role under the proposed new draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Northern Ireland Human Rights Association was represented by Professor Brice Dickson, Chief Commissioner. 3.18pm Mr Maginness returned to the meeting. 3.43pm Mr Paisley left the meeting. 6. Any other business No other matters were raised. 7. Date and time of next meeting The Committee agreed that it would next meet on Monday, 17 June 2002, when it would hear evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland and the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. 3.49pm the Chairperson adjourned the meeting. Mr Gregory Campbell MLA 17 June, 2002 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS THURSDAY 17 JUNE 2002 Present: Mr Gregory Campbell MLA,

Chairperson Attendees: Mr Tony Logue, Committee Clerk Apologies: Mr David Ervine MLA 2.13pm the Chairperson opened the meeting in public session. 1. Apologies The apologies were noted. 2. Draft Minutes of Proceedings Resolved, That the draft Minuts of Proceedings for Tuesday, 13 2002 be agreed. 3. Matters arising There were no matters arising. 4. Evidence Session Members noted the contents of a written brief from the Law Society of Northern Ireland on the proposed Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland ) Order 2002. 2.15pm The Chairperson called the Law Society of Northern Ireland to be examined. 0.1 Members heard evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland on their role under the proposed new Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The Law Society of Northern Ireland was represented by Mr Joe Donnelly, Junior Vice President, Mr Paddy Kinney, Law Society Representative, Mr Barra McGrory, Law Society Representative and Mr John Bailie, Chief Executive. 2.31pm Ms Lewsley joined the meeting. 2.36pm Mr Kelly left the meeting. 2.55pm The evidence session closed. 0.2 It was agreed that the Committee would adjourn until 4.00pm when evidence would be taken from the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland. As the Chairperson would be unable to attend, it was further agreed to elect a co-opted Chairperson. 3.07pm Mrs Bell left the meeting. 3.07pm Mr McLaughlin left the meeting. 3.07pm The Chairperson adjourned the meeting until 4.00pm and left. 4.07pm Mr Hendron, Professor McWilliams, Mr Murphy and Mr Shannon joined the meeting. 4.07pm the meeting opened in public session-the Clerk in the Chair. 5. Co-option of Chairperson In the absence of the Chairperson, the Clerk called for nominations for the position of co-opted Chairperson. Professor McWilliams proposed that Ms Lewsley be the co-opted Chairperson for this meeting. Dr Hendron seconded this and the nomination was accepted. On their being no further nominations the Clerk put the question without debate. Resolved, that Ms Lewsley, being the only candidate proposed, be the Chairperson of this Committee meeting. 6. Evidence Session Members noted the contents of a written brief from the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland on the proposed Draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. 4.08pm The Chairperson called the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland to be examined. Members heard evidence from the General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland on their role under the proposed new draft Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2002. The General Council of the Bar of Northern Ireland was represented by Mr Stuart Beattie QC, Mr David Hunter QC and Mr Jim McNulty QC. 4.10pm Mr Beggs joined the meeting. 4.45pm Mr Murphy left the meeting. 4.55pm Professor McWilliams left the meeting. 7. Any other business No other matters were raised. 8. Date and time of next meeting The Committee agreed that the next meeting would take place on Monday 24 June 2002 at 1.30pm to consider a draft Report of the Committee's proceedings. 4.58pm the Chairperson adjourned the meeting. Ms Patricia Lewsley MLA 24 June, 2002 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS THURSDAY 24 JUNE 2002 Present: Mr Gregory Campbell MLA,