Committee on Standards and Privileges

Report on the Committee Inquiry on enforcing the

Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating

to the Conduct of Members and the Appointment

of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee,

Minutes of Evidence, Issues Paper and Written Submissions and

other Evidence Considered by the Committee Relating to the Report

Ordered by The Committee on Standards and Privileges to be printed 18 May 2010

Report: NIA 40/09/10R Committee on Standards and Privileges

Session 2009/2010

Third Report

Powers and Membership

1. The Committee on Standards and Privileges is a Standing Committee of the Northern Ireland Assembly established in accordance with paragraph 10 of Strand One of the Belfast Agreement and under Assembly Standing Order No. 57.

2. The Committee has power:

- to consider specific matters relating to privilege referred to it by the Assembly;

- to oversee the work of the Assembly Clerk of Standards;

- to examine the arrangement for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of the Register of Members’ Interests and any other registers of interest established by the Assembly, and to review from time to time the form and content of those registers;

- to consider any specific complaints made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests referred to it;

- to consider any matter relating to the conduct of Members, including specific complaints in relation to alleged breaches of any code of conduct to which the Assembly has agreed and which have been drawn to the Committee’s attention;

- to recommend any modifications to any Assembly code of conduct as may from time to time appear to be necessary.

3. The Committee is appointed at the start of every Assembly, and has power to send for persons, papers and records that are relevant to its enquiries.

4. The membership of the Committee is as follows:

Mr Declan O’Loan, Chairperson 1

Mr Willie Clarke, Deputy Chairperson 2

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Thomas Buchanan 3

Mr Trevor Clarke 4,5

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Mickey Brady 6,10

Mr Paul Maskey 7,8

Mr Alastair Ross 9

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

5. The Report and evidence of the Committee are published by the Stationery Office by order of the Committee. All publications of the Committee are posted on the Assembly’s website: (archive.niassembly.gov.uk.)

6. All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of Standards, Committee on Standards and Privileges, Committee Office, Northern Ireland Assembly, Room 284, Parliament Buildings, Ballymiscaw, Stormont, Belfast BT4 3XX. Tel: 02890 520333; Fax: 02890 525917; e-mail: committee.standards&privileges@niassembly.gov.uk

1 Mr Declan O’Loan replaced Mrs Carmel Hanna with effect from 3 July 2009

2 Mr Willie Clarke replaced Mr Gerry McHugh as Deputy Chairperson with effect from 21 January 2008

3 Mr Thomas Buchanan replaced Mr David Hilditch with effect from 14 September 2009

4 Mr Jonathan Craig replaced Mr Alex Easton with effect from 15 September 2008

5 Mr Trevor Clarke replaced Mr Jonathan Craig with effect from 14 September 2009

6 Mr Billy Leonard replaced Mr Francie Brolly with effect from 11 January 2010

7 Mrs Claire McGill replaced Mr Gerry McHugh with effect from 28 January 2008

8 Mr Paul Maskey replaced Ms Claire McGill with effect from 20 May 2008

9 Mr Alastair Ross replaced Mr Adrian McQuillan with effect from 29 May 2007

10 Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Billy Leonard with effect from 19 April 2010

Table of Contents

Report

Key Issues and Conclusions and Recommendations

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee Relating to the Report

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Issues Paper and Written Submissions

Appendix 4

Other evidence considered by the Committee

Executive Summary

The Committee on Standards and Privileges has completed its inquiry on the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards, on maintaining the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members (the Code of Conduct), and on handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct. The aim of the inquiry was to establish the most appropriate means of maintaining the Assembly’s Code of Conduct and handling alleged breaches in relation to it.

The Committee has concluded that, broadly speaking, the principles of the existing system whereby the Northern Ireland Assembly regulates its own affairs and ultimately takes decisions on complaints that have been made against Members of the Assembly is an appropriate, reasonable and workable system.

However, while these principles are sound there is important work that can and should be done in order to ensure that in practice the system is more robust, and is seen to be both fairer and more transparent.

The most significant aspect of this is that the Assembly should have its own Commissioner for Standards whose role would be to carry out independent objective investigations into complaints against Members and to present his or her findings to the Committee on Standards and Privileges. The role of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be set out on a statutory basis. The powers of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards, including the power to call for witnesses and documents, should be set out in statute. The Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ independence from the Assembly in respect of specific investigations should also be set out in statute.

The Assembly should therefore pass a Bill to create a statutory Assembly Commissioner for Standards during this current mandate and there should be an open competition for the position of Assembly Commissioner for Standards which would enable the appointed Commissioner to take up his or her post as soon as possible after the start of the next mandate.

Summary of Recommendations

Recommendation 1

In relation to modifying and maintaining the Assembly’s Code of Conduct the current respective roles and duties of the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly are appropriate.

Recommendation 2

In relation to handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct the existing fundamental roles (whereby the Commissioner investigates; the Committee determines whether a breach has occurred; and the Assembly’s role is in respect of the imposition of sanctions) should remain the same.

Recommendation 3

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to initiate his or her own investigation into the conduct of a Member.

Recommendation 4

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to carry out investigations into matters relating to the conduct of Members referred to him or her by the Clerk/Director General in respect of issues relating to the Clerk/Director General’s role as Accounting Officer.

Recommendation 5

The power to dismiss a complaint as inadmissible should remain with the Committee, with the Commissioner continuing to provide advice to the Committee.

Recommendation 6

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to include in any report an indication of the seriousness of any breach as a guide to what might be an appropriate sanction.

Recommendation 7

There should not be a formal appeals mechanism as part of the Assembly’s process to consider complaints against Members.

Recommendation 8

The role of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be set out on a statutory basis.

Recommendation 9

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ powers, including the power to call for witnesses and documents, should be set out in statute.

Recommendation 10

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ independence from the Assembly in respect of specific investigations should be set out in statute.

Recommendation 11

Legislation should provide that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards shall not be dismissed unless – (a) the Assembly so resolves; and (b) the resolution is passed with the support of a number of members which equals or exceeds two-thirds of the total number of votes cast.

Recommendation 12

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ specific salary and terms and conditions should be determined by the Assembly Commission but should be broadly commensurate with comparable office holders.

Recommendation 13

There should be an open and transparent competition consistent with the principles of best practice in relation to public appointments for the position of Assembly Commissioner for Standards. The appointment should be for a one off term of five years and should be approved by a resolution of the Assembly.

Recommendation 14

The Assembly Commissioner for Standards should report to the Assembly by means of an Annual Report.

Recommendation 15

The Assembly should pass a Bill to create a statutory Assembly Commissioner for Standards during this current mandate.

Recommendation 16

Standing Orders should be amended in order to enable the implementation of the conclusions and recommendations of this report.

Introduction and Background

1. Further to the completion of the Committee on Standards and Privileges’ review of the Assembly’s Code of Conduct and the introduction of its specific requirements in October 2009, the Committee then agreed to carry out an inquiry on the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards (the Commissioner), on maintaining the Code of Conduct and on handling alleged breaches in relation to it.

2. In doing so the Committee not only recognised that it needed to formalise its arrangements in relation to the Commissioner (whose role has been carried out on an interim basis for a number of years), but also that it needed to give consideration to what the respective roles that the Commissioner, the Committee and the Assembly should be, both in terms of maintaining the Code of Conduct and in terms of handling alleged breaches of it.

3. The Committee on Standards and Privileges from a previous mandate had held an inquiry into the possible appointment of a Commissioner and reported on the matter in February 2001. The Committee concluded at that time that a Commissioner should be appointed to investigate complaints against Members of the Assembly but that the then existing system whereby the Northern Ireland Assembly regulated its own affairs and ultimately took decisions on complaints made against Members was appropriate, reasonable and workable. The Committee also stated that it would discuss with the Assembly Commission the terms and conditions of employment of a Commissioner and the process of recruiting a Commissioner.

4. The Committee also agreed interim arrangements to ensure that in the intervening period complaints against Assembly Members were subject to entirely independent investigation. The Committee concluded that the Office of the Assembly Ombudsman was well placed and equipped to discharge the functions of a Commissioner on an interim basis, as it had all of the investigative infrastructure, skills and experience to investigate complaints against Assembly Members. This interim arrangement is the arrangement that is still in place today and the current Committee is extremely grateful to the Ombudsman and his office for the diligent service that they have provided and continue to provide.

5. After having asked the Ombudsman to act as the Interim Commissioner, the Committee later decided that rather than carrying out an appointment process to recruit an individual as Commissioner it would be more appropriate if it was to introduce a Bill that would make the role of Commissioner a statutory function of the Office of the Ombudsman. A Bill was introduced by the Committee which reached second stage before falling as a result of suspension.

6. The current Committee noted what had previously occurred and agreed that a new inquiry needed to be carried out. The previous inquiry was carried out nine years ago. Since then the whole context of the accountability of public representatives has changed significantly, not least with regards to the issue of the perceived effectiveness of self-regulation. The Committee considered that it was appropriate for it to consider all the options open to it in terms of ensuring that Members are held to account within the context of the Code of Conduct.

Terms of Reference

7. The aim of the inquiry was therefore to establish the most appropriate means of maintaining the Code of Conduct and handling alleged breaches in relation to it.

In doing so, the Committee wanted to consider:

- What the role, responsibilities and powers of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be;

- whether the position of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be placed on a statutory basis;

- how an Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be appointed;

- what the terms and conditions of any appointment might be;

- what the role of the Committee on Standards and Privileges should be in dealing with alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct; and

- what the role of the Assembly should be in dealing with alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct.

In order to come to a conclusion on these matters the Committee sought to answer the following questions:

In terms of modifying and maintaining the Code of Conduct:

- Are the current respective roles and duties of the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly appropriate?

- Should there be any formal role for others in terms of maintaining and modifying the Code of Conduct?

In terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct:

- Are the current respective roles and duties of the Commissioner for Standards, the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly appropriate?

- Should there be any formal role for others in terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct?

- Should consideration be given to introducing any sort of appeals procedure in relation to decisions reached by the Committee?

In terms of appointing an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

- What should the role, responsibilities and powers of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards be?

- Existing Standing Orders state that the Commissioner shall not, in the exercise of any function, be subject to the direction or control of the Assembly. Is this appropriate?

- Existing Standing Orders say that the Commissioner shall not be dismissed unless – (a) the Assembly so resolves; and (b) the resolution is passed with the support of a number of members which equals or exceeds two-thirds of the total number of seats in the Assembly. Is this appropriate?

- Should the position of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards be placed on a statutory basis?

- Should an Assembly Commissioner for Standards have statutory powers?

- How should an Assembly Commissioner for Standards be appointed?

- What should be the eligibility criteria of any such appointment?

- What should be the terms and conditions of any appointment?

- Are there any other relevant issues which should be brought to the Committee’s attention in relation to the aim of the inquiry and its terms of reference?

Conduct of the Inquiry

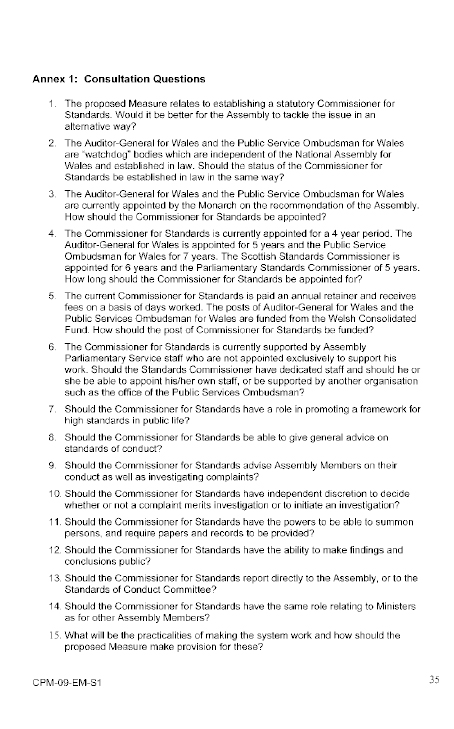

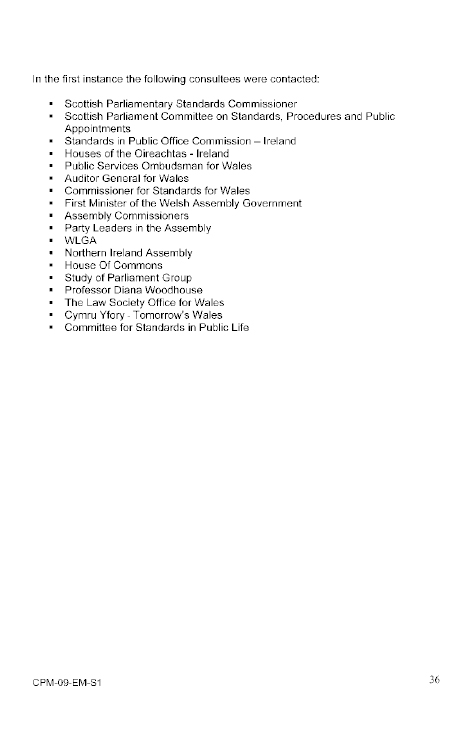

8. Further to having agreed the terms of reference for the inquiry, the Committee issued a public notice, drafted an issues paper and wrote to relevant stakeholders, including each of the political parties at the Assembly, inviting written submissions. A number of written submissions were received and these, together with the Committee’s issues paper, are set out in Appendix 3.

9. The Committee subsequently took oral evidence from the Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards; the Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland; the National Assembly for Wales’s Committee on Standards of Conduct; the Committee on Standards in Public Life and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. This evidence is included at Appendix 2. In addition, the Committee visited the Houses of the Oireachtas where it met with Dáil Éireann’s Committee on Members’ Interests and the Standards in Public Office Commission. The Committee is very grateful to all of those who took the time to provide the Committee with written and oral evidence.

10. The Committee also commissioned a research paper from the Northern Ireland Assembly Research Services which is included at Appendix 4.

Key Issues and Conclusions and Recommendations

Modifying and Maintaining the Code of Conduct

11. In terms of modifying and maintaining the Code of Conduct the Committee asked:

- Are the current respective roles and duties of the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly appropriate?

- Should there be any formal role for others in terms of maintaining and modifying the Code of Conduct?

The Committee on Standards and Privileges currently has responsibility for recommending modifications to the Code of Conduct while the Assembly currently has responsibility for agreeing modifications to the Code of Conduct (further to recommendations from the Committee on Standards and Privileges).

12. While there were those who argued for an end to any sort of self-regulation, the majority of respondents were satisfied that the current arrangements (in terms of the respective roles and duties of the Committee on Standards and Privileges, and the Assembly) were appropriate. This was emphasised by the Committee on Standards in Public Life and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission, as well as others. The Committee agrees that it is important in terms of the Assembly’s credibility that the Assembly is seen to be showing leadership in respect of conduct matters and this means taking responsibility for developing its own Code of Conduct. Members should have a sense of ownership of the Code of Conduct and its values and principles. The Code should represent the collective view of the Assembly as to what it agrees constitutes appropriate and acceptable behaviour. Such ownership enables the Assembly to foster from within a culture that promotes and maintains ethical behaviour.

13. That point not withstanding, some respondents did see a role for the Commissioner in terms of being consulted from time to time about whether any areas of the Code might need modifying. The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission also commented on the appropriateness of the Assembly carrying out public consultations in respect of proposed amendments to the Code. In fact both of these suggestions reflect current practice. The Committee agrees that it is appropriate that the Commissioner (who has responsibility for interpreting the Code during the course of investigations) should be able to draw to the Committee’s attention areas of the Code which may need to be reviewed or amended. Equally the Committee is of the view that it is appropriate to carry out public consultation before recommending any substantive amendments to the Code of Conduct.

14. The Committee therefore recommends that in relation to modifying and maintaining the Assembly’s Code of Conduct the current respective roles and duties of the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly are appropriate.

Handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct

15. In terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct the Committee asked:

- Are the current respective roles and duties of the Commissioner for Standards, the Committee on Standards and Privileges and the Assembly appropriate?

- Should there be any formal role for others in terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct?

- Should consideration be given to introducing any sort of appeals procedure in relation to decisions reached by the Committee?

16. The Commissioner currently has responsibility for receiving complaints; recommending to the Committee on Standards and Privileges that complaints are inadmissible; investigating admissible complaints; making reports to the Committee on Standards and Privileges on admissible complaints with a recommendation on whether or not the conduct complained of represents a breach of the Code of Conduct; and recommending the use of the rectification procedure (where appropriate). The Committee currently has responsibility for dismissing complaints brought to its attention by the Commissioner which it considers to be inadmissible; considering reports on admissible complaints from the Commissioner and, further to this, determining whether breaches of the Code of Conduct have occurred; recommending to the Assembly that specific sanctions be imposed upon Members who have breached the Code of Conduct; and allowing for the use of the rectification procedure (where appropriate). The Northern Ireland Assembly currently has responsibility for imposing sanctions upon Members who have breached the Code of Conduct (further to reports from the Committee on Standards and Privileges).

17. There were some respondents to the consultation who were opposed to any sort of self-regulation and who therefore effectively disagreed that the current respective roles in respect of handling complaints are appropriate. A specific point that was made in this regard was that it should be the role of the Commissioner not only to investigate alleged breaches of the Code but also to ultimately determine whether or not the Code has been breached and then, where he or she considers it appropriate, to impose sanctions. However, having considered all of the evidence and the arrangements in other places the Committee is satisfied that it would not be appropriate for the range of roles and powers to be vested in one individual who would have unilateral responsibility for enforcing the Code.

18. This view was supported by most respondents, who felt that the fundamentals of the existing system were appropriate (the fundamentals being that the Commissioner should investigate; the Committee should determine whether a breach has occurred; and the Assembly’s role should be in respect of the imposition of sanctions). It is therefore recommended that these fundamental roles should remain the same. However, there was a variety of views on the specific details of how these roles should operate in practice, particularly in respect of the role of the Commissioner. This is set out in further detail below.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to carry out an investigation

19. One such area where there were differing views was on the question of whether the Commissioner should be able to initiate his or her own investigation into the conduct of Members without having first received a complaint. The Committee on Standards in Public Life was of the firm view that the Commissioner must be able to initiate his or her own inquiries. The Committee on Standards in Public Life said that this was a matter of ensuring public confidence and for that reason it had also made the same recommendation to the Committee on Standards and Privileges at the House of Commons. The Assembly Commission was also of the view that the Commissioner should be able to initiate his or her own investigation. The Committee agrees that the rationale in calling for the Commissioner to have such a power is sound.

20. Others had some concerns with this proposal. In particular the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission warned that having the power of discretion could call into question the Commissioner’s judgement whenever he or she decides whether or not to investigate a matter.

21. It is understandable that there might be concerns about the practicalities of how a Commissioner might choose to initiate his or her own investigation into the conduct of a Member. However, the Committee is of the view that not only can these concerns be addressed, they are outweighed by the consequences of not allowing the Commissioner to initiate his or her own investigation. It is not acceptable that where there are significant, legitimate and evidential concerns in relation to the conduct of Members but where no formal complaint has been made that no investigation should be carried out. If there was no investigation in such circumstances it would undermine public confidence in the integrity of the Assembly.

22. It is therefore recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to initiate his or her own investigation into the conduct of a Member. However such an investigation should only be carried out where the Commissioner is satisfied that there is a prima facie evidential basis to justify an investigation. The Commissioner could make preliminary enquiries in respect of a Member’s conduct before concluding that a ‘self-start’ investigation was appropriate.

23. A further suggestion in respect of how the Commissioner might begin an investigation was made by the Speaker on behalf of the Assembly Commission. The Assembly Commission suggested that the Clerk/Director General, as Accounting Officer, should be able to consider any potential breaches by Members of the rules set out in determinations under s47 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 or of the new Members’ Financial Services Handbook and where concerns exist to refer the matter to the Commissioner. The Commissioner could then carry out an investigation in order to establish whether or not a Member had breached the Code of Conduct.

24. The Committee understands that such a proposal would be consistent with either practice or principle in other places. The Committee believes that enabling the Clerk/Director General to refer matters in this way would strengthen public confidence in respect of the measures that exist to ensure that abuses of allowances should not occur. It is not anticipated that such a proposal would significantly impact upon the required resources or workload of the Commissioner. It is therefore recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to carry out investigations into matters relating to the conduct of Members referred to him or her by the Clerk/Director General in respect of issues relating to the Clerk/Director General’s role as Accounting Officer.

25. In addition to this the Committee should retain its power to refer a matter to the Commissioner for investigation, although the Committee envisages that it would only ever use this power in exceptional circumstances. It would not be satisfactory for this power to be relied upon exclusively in order to ensure that investigations are carried out in the absence of complaints.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to dismiss a complaint

26. A further issue that emerged during the inquiry was the question of whether or not the Commissioner should be able to dismiss complaints as being inadmissible without any reference to the Committee. It is currently the case that the Commissioner considers a complaint against the agreed admissibility criteria and where he considers that a complaint is inadmissible he advises the Committee of this. The Committee considers the advice provided and must decide whether it agrees. It should be noted that in the case of complaints that the Commissioner considers to be admissible there is no need to seek the Committee’s agreement to have these investigated.

27. The Committee recognised that there could be some value in having a mechanism which would mean that clearly inadmissible complaints received by the Commissioner did not have to come to its attention. However, the Committee also noted that there has not previously been large numbers of such complaints. Furthermore, while some complaints are clearly inadmissible other complaints may be more borderline in terms of their admissibility. Granting the Commissioner the power to determine whether or not complaints such as these should be investigated would fundamentally alter the Commissioner’s role. The Commissioner would effectively become a decision taker in terms of the outcome where someone had sought to make a complaint. The Committee agrees that it does not think that dismissing complaints should be part of the Commissioner’s role. The Committee therefore recommends that the power to dismiss a complaint as inadmissible should therefore remain with the Committee, with the Commissioner continuing to provide advice to the Committee.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to recommend a sanction

28. Standing Orders currently prevent the Commissioner from recommending a sanction to be imposed upon a Member, other than in respect of the rectification procedure. The Committee on Standards in Public Life called for the Commissioner to be able to include in any report an indication of the seriousness of any breach as a guide to what might be an appropriate sanction. During oral evidence it was clarified that this suggestion did not extend to allowing the Commissioner to actually suggest specific sanctions. No-one raised any objection to this particular suggestion. In practice the Commissioner can already indicate the seriousness of a breach through the use of language to describe the conduct. The Committee is therefore content that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be able to include in any report an indication of the seriousness of any breach as a guide to what might be an appropriate sanction.

Formal role for others in terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct

29. The Committee asked whether there should be a formal role for others in terms of handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct. The Committee asked this question in terms of establishing roles additional to those existing roles for others (e.g. for the Police Service of Northern Ireland when a complaint is received which also raises questions of criminal liability). There was one substantial suggestion in this regard. The Committee on Standards in Public Life recommended that the Committee on Standards and Privileges should have at least two lay members with full voting rights. It was argued that the inclusion of lay membership on the Committee would be a useful step in enhancing public acceptance of the robustness and independence of the Assembly’s governance arrangements in relation to the conduct of members.

30. A further matter arose in relation to the composition of the Committee. It was established that the Committee on Standards of Conduct at the National Assembly for Wales has been reduced in number of members. Previously, its composition reflected the party composition of the Assembly with different numbers of members from each party on the committee depending on party strength (as is also currently the case at the Northern Ireland Assembly). However, further to the Government of Wales Act 2006, the Committee on Standards of Conduct has become a much smaller committee with just four members: one from each major party in the Assembly. In that sense even though all the major parties are represented it is not party balanced.

31. Unlike other committees which quite properly come to decisions informed by party political considerations, standards committees always emphasise the importance of their members divesting themselves of party political allegiances when making decisions. When this principle is accepted it means the case for constituting such a committee based on party strength may be no longer compelling.

32 The Committee recognises the rationale for the proposal to appoint two independent lay members. The Committee also understands the reasoning for reducing the number of elected members on a standards committee. The Committee notes that the Committee on Standards and Privileges at the House of Commons had indicated that it will appoint independent lay members and that the Committee on Standards of Conduct at the National Assembly for Wales considers that reconstituting its committee with fewer members has improved its decision making ability.

33. The Committee is committed to introducing a system for overseeing the conduct of Members that is seen to be both robust and depoliticised. The Committee recognises that altering its composition by reducing the number of elected members and appointing two independent lay members could contribute to this aim.

34. Accordingly, the Committee has already begun considering the detail of how it might appoint and hold to account independent lay members. However, the Committee wishes to explore further some of these practicalities with its counterpart committee at the House of Commons and other places before taking final decisions on how such an approach could work at the Assembly.

Appeals procedure in relation to decisions reached by the Committee

35. The Committee asked if consideration should be given to introducing any sort of appeals procedure in relation to decisions reached by the Committee. The response to this question was varied. Some respondents were firmly of the view that an appeals procedure was necessary. However, others disagreed.

36. The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission said that in its view there can be no appeal from the Committee unless to the full Assembly. However, it went on to say that as the Assembly has devolved the enforcement role to the Committee, no practical purpose would be served by the Assembly giving itself an appellate role which would deprive the Committee of its raison d’être. The Committee on Standards in Public Life pointed out that in the most serious cases (i.e. those cases where the Committee finds that a breach has occurred and recommends imposing a sanction) it is ultimately up to the Assembly to decide whether or not to accept the Committee’s decision.

37. The Committee gave careful consideration to this issue. The most significant ‘decision’ against which one might consider having an appeals process is any decision by the Assembly to impose a sanction upon a Member. However, the practicalities of introducing such an appeals process would be fraught with difficulties, not least the question of to whom such appeals would be made. The Committee agrees that it is not possible to identify a practical and desirable appellate jurisdiction, a point which had been made by the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. It is therefore recommended that there should not be a formal appeals mechanism as part of the Assembly’s process to consider complaints against Members.

38. The Committee also agreed that in the absence of an appeal mechanism it is of critical importance to ensure that there is procedural fairness in the process for considering complaints. The Committee is of the view that the existing process for considering complaints is procedurally fair but that nonetheless it should give consideration to whether there are any further measures that could be taken in order to bolster procedural fairness. One particular issue that the Committee has identified is enhancing the existing opportunity for Members who are subject to investigation to participate and contribute to proceedings once the Commissioner’s report has been sent to the Committee.

39. It should be noted that in considering the question of appeals the Committee recognised that there is a limited potential for judicial review of any Assembly decision. The Committee also noted that existing practice allows for the Commissioner to carry out a fresh investigation into the conduct of a Member where a complaint appears to provide new evidence in relation to a previous complaint.

Appointing an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

40. In the final section of the Committee’s issues paper on appointing a Commissioner the Committee asked:

- What should the role, responsibilities and powers of a Commissioner be?

- Existing Standing Orders state that the Commissioner shall not, in the exercise of any function, be subject to the direction or control of the Assembly. Is this appropriate?

- Existing Standing Orders say that the Commissioner shall not be dismissed unless – (a) the Assembly so resolves; and (b) the resolution is passed with the support of a number of members which equals or exceeds two-thirds of the total number of seats in the Assembly. Is this appropriate?

- Should the position of a Commissioner be placed on a statutory basis?

- Should a Commissioner have statutory powers?

- How should a Commissioner be appointed?

- What should be the eligibility criteria of any such appointment?

- What should be the terms and conditions of any appointment?

- Are there any other relevant issues which should be brought to the Committee’s attention in relation to the aim of the inquiry and its terms of reference?

There were a variety of responses to these questions; on some there was a large degree of consensus, on others more of a divergence of opinion.

41. On the issue of whether the Commissioner’s role should be placed on a statutory basis there was widespread support for this proposal with the exception of those who felt that to do so would introduce an unnecessary risk of judicial review. However, the Committee is satisfied that in the context of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and the Northern Ireland Assembly, placing the Commissioner on a statutory footing will not in itself have the effect of making the Commissioner, the Committee or the Assembly more open to challenges by way of judicial review in respect of the fairness of decision making processes than is currently the case.

42. Consideration was given as to whether the Commissioner’s sole role should be to carry out investigations and report to the Committee on Standards and Privileges (as provided in Standing Order 69A). The additional circumstances in which the Commissioner might carry out an investigation are referred to above. The Committee is satisfied that the Commissioner should also be able to offer opinions not just in respect of specific investigations into the conduct of Members but also on more general issues in relation to the Committee’s role and into the conduct of Members (e.g. the Code of Conduct or the form or content of the Register of Members’ Interests).

43. In addition, the Committee noted that in some other places the Commissioner has a role in terms of providing advice and guidance in respect of Members’ requirements to register and declare interests. At the Assembly (and other places), however, it is the Clerk of Standards who provides advice and guidance to Members on the registering and declaring of interests. The Committee concluded that this arrangement works well and should continue. Firstly, the Clerk of Standards works in Parliament Buildings on a full-time basis and is therefore easily accessible for all Members at any time during the working week. Secondly, a question emerges as to whether or not there would be a conflict of interest where the Commissioner was asked to carry out an investigation into circumstances where he or she had already provided advice to the Member against whom the complaint was being made.

44. The Committee believes that placing the role of a Commissioner on a statutory basis would demonstrate the Assembly’s commitment to introducing robust measures to govern the conduct of Members. Being placed on a statutory basis should strengthen public confidence in terms of the Commissioner’s independence. It would also provide the Commissioner with greater protection and authority. It is therefore recommended that the role of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should be set out on a statutory basis.

45. The Committee was advised of some of the specific statutory powers that an independent Commissioner should have. These included the power to call for witnesses and documents; statutory protection from defamation (privilege); power to secure the provision of goods and services; and protection from the requirement to disclose information. The Committee agrees that the Commissioner needs to have all the powers necessary in order to be able to carry out a full unhindered independent investigation into any admissible complaint. Most important of these is the power to call for witnesses and documents. It should be an offence not to cooperate with an investigation of the Commissioner. The definitive range of powers which the Commissioner should have can be finalised as part of the process that will lead to legislation being made. However, at this current stage the Committee believes that it is important that the Assembly indicate that these powers should be statutory powers. It is therefore recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ powers, including the power to call for witnesses and documents, should be set out in statute.

46. All respondents agreed that it was appropriate that the Commissioner should not be subject to the direction or control of the Assembly, although some responses helpfully clarified that this was within the context of an overall agreed procedural framework. It is important to explain what is meant by the Committee in respect of the Commissioner’s independence and freedom from the direction and control of the Assembly. It is not the case that the Committee should be entirely passive in respect of how investigations are carried out. Rather, the Committee has particular expectations in respect of any investigation, and these expectations are set out in the protocols and procedures that inform the Commissioner’s work. Nor is it the case that the Committee should not be able to ask the Commissioner to consider specific issues in relation to a particular investigation. It would not be appropriate, for example, if further to having considered a report from the Commissioner the Committee could not ask the Commissioner to go back and establish or clarify particular points.

47. Rather, the important issue in terms of the Commissioner’s independence is that neither the Committee nor the Assembly should be able to prevent the Commissioner from carrying out an investigation if the Commissioner believes that an investigation is appropriate. Furthermore, once the Commissioner has decided to carry out an investigation neither the Committee nor the Assembly should be able to prevent the Commissioner from reaching and expressing any particular conclusions on the outcome of that investigation. In support of this important principle, and in order to promote transparency, the Committee will always publish any reports of the Commissioner in full in its own reports to the Assembly. In this way the independence of the Commissioner will be safeguarded and his or her findings will always be a matter of public record. It is therefore recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ independence from the Assembly in respect of specific investigations should be set out in statute.

48. The Committee asked a question in relation to the existing provision which says that the Commissioner shall not be dismissed unless – (a) the Assembly so resolves; and (b) the resolution is passed with the support of a number of Members which equals or exceeds two-thirds of the total number of seats in the Assembly. The Committee believes that it is important that there is a safeguard in place which means that the Commissioner cannot easily be dismissed and that this safeguard is placed on a statutory basis. The absence of such a safeguard could be perceived as a threat to the ability of the Commissioner to reach unpopular conclusions. However, the Committee also noted that the existing requirement is actually much more stringent than the accountability requirements for Commissioners in other places. At both the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales such a resolution would require the number of votes cast in favour to be no less that two-thirds of the total number of votes cast (as opposed to two-thirds of the total number of seats). At the House of Commons such a resolution could be agreed by simple majority. The Committee considers that the requirements of the Scottish Parliament and National Assembly for Wales are more appropriate in the case of the Northern Ireland Assembly. It is therefore recommended that it be set out in statute that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards shall not be dismissed unless – (a) the Assembly so resolves; and (b) the resolution is passed with the support of a number of Members which equals or exceeds two-thirds of the total number of votes cast.

Appointing the Assembly Commissioner for Standards

49. The issue of how the Commissioner should be appointed was one where there was broadly a consensus. The majority of respondents who commented felt that there should be a fair and open competition for a one off term of appointment. The Committee was particularly grateful for the advice of the Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland who emphasised this point and who offered to provide support and guidance to the Assembly in any appointment process. The Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland has developed principles of best practice for public appointments and although her statutory remit does not extend to appointments of the Assembly the Committee nonetheless recognises the significance of these principles. Any appointment must be made on merit, in a fair and open way, with equality of opportunity for everyone.

50. The only alternative considered to making such an appointment was the option of making statutory arrangements for an existing separate office holder to carry out the role of Commissioner (similar to the existing interim arrangements). However, the Committee considered that some difficulties could arise as a result of making statutory arrangements for an existing separate office holder to carry out the role. Firstly, the Assembly would effectively lose its ability to both appoint and dismiss a Commissioner. Secondly, although it is the case that the Commissioner’s post will be part-time there may be occasions when the Commissioner would have to be able to work such hours as are necessary in respect of particular investigations. The Committee would need to be satisfied that a Commissioner with another primary role would be able to guarantee that the work of Commissioner could always be prioritised. Finally, having looked at the issue of costs, and having been advised by the Assembly Commission that it could (if required) provide administrative support to the Commissioner (as opposed to setting up a stand alone office), the Committee is of the view that having a separate existing office holder carry out the role would not deliver any significant level of efficiencies. None of this is to say, however, that an existing office holder who met the eligibility criteria could not be appointed through an open competition and in such circumstances it would be sensible to look at using their existing administrative support.

51. The one off term of appointment is an important feature of the Commissioner’s independence. A Commissioner who has to carry out an investigation into a Member who he or she may later rely upon in order to seek reappointment could be perceived to be a Commissioner who has a vested interest in concluding that that Member has not breached the Code. The Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland recommended a one off term of appointment of five years. The Committee is content with this proposal. The Committee agrees with the Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland that this term would allow the appointee the opportunity to ‘commit to a long term plan of work without looking over his shoulder wondering whether a re-appointment will come’.

52. In terms of the eligibility criteria for the Commissioner the Committee on Standards in Public Life said that they should include independence of mind and an ability to be robust against improper pressure. The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission said that the Commissioner needs to be someone who is above reproach, enjoys full public confidence and ought to be subject to the same disclosure requirements as apply to those whom they regulate. The Committee agrees with all of these suggestions. However, the Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland said that the matter of criteria for the post first requires a clear definition of the duties and powers within legislation. Only then should a role specification and appropriate criteria be drawn up. The Committee accepts this advice and will await the outcome of the legislative process before seeking to define the eligibility criteria for the post of Commissioner. However, it goes without saying that the Commissioner must be someone who has the skills and experience necessary to carry out investigations and can demonstrate that they will be both independent and impartial.

53. Respondents did not seek to comment on the terms and conditions of any appointment, except for the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission who said that the terms on which the Commissioner serves should be broadly aligned with comparable public offices. The Committee has noted the particular arrangements which exist in Wales (where remuneration is provided on a per diem basis plus an annual retainer sum) and believes that such an arrangement would work well here. However, as it is the Assembly Commission that would fund the post of Commissioner the Committee is satisfied that it should take the final decision in respect of remuneration. It is recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards’ specific salary and terms and conditions should be determined by the Assembly Commission but should be broadly commensurate with comparable office holders.

54. There are different means of carrying out a fair and open appointment process. The Assembly Commission has suggested using the process which was used for the appointment of the Comptroller and Auditor General and it appears to the Committee that this is a sound and viable option. The Committee will agree the specifics of the appointment process with the Assembly Commission and will consult the Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland on its proposals. Whatever process is finally agreed, however, ultimately the Committee believes that the Commissioner should be appointed by a resolution of the Assembly.

55. It is therefore recommended that there should be an open and transparent competition consistent with the principles of best practice in relation to public appointments for the position of Assembly Commissioner for Standards. The appointment should be for a one off term of five years and should be approved by a resolution of the Assembly. Such an appointment would be consistent with models elsewhere, consistent with best practice on public appointments and need not lead to any significant additional resources being required.

Other issues

56. The Assembly Commission has indicated that it could provide the necessary funding for the office of the Commissioner. The Committee welcomes this. It is of crucial importance that the Commissioner has whatever resources are necessary to allow him or her to effectively carry out the role. Clearly it would undermine the whole purpose of introducing a statutory independent Commissioner if that Commissioner was then to be constrained through lack of resource. The Committee recognises that it will be necessary for a bid to be made within the wider Assembly budget for the necessary level of resources. Nonetheless, having looked at current costs, and costs in other places, the Committee is satisfied that the costs involved in providing the required resources are unlikely to be significant. The Committee attaches great importance on the Commissioner receiving all the resources necessary in order to carry out his or her duties effectively and recommends that the Assembly Commission consider this as a similarly significant priority.

57. Of course the provision of such resources will require accountability mechanisms to be put in place and there will be areas of overlap between the Commissioner’s role and accountability to both the Committee and the Assembly Commission. The Assembly Commission has also pointed to its ongoing work to establish an Independent Statutory Body for the determination of pay, pension and financial support for Members. The Assembly Commission has raised the potential role of the Independent Statutory Body and its possible involvement in the appointment process of the Commissioner. The Committee will explore these issues in further detail with the Assembly Commission. However, in addition to whatever governance arrangements are put in place, it is also recommended that the Assembly Commissioner for Standards should report to the Assembly by means of an Annual Report.

58. Further work will be required in order to implement the recommendations in this report. Most significantly, legislation will need to be introduced and standing orders will need to be amended. This should be done in advance of the next mandate. In respect of the required legislation, the Committee could proceed with its own Bill. However, given the Assembly Commission’s work to establish an Independent Statutory Body, a further option is for the necessary legislative provisions to be included in a Bill to enable the establishment of such a body. Such an approach would generate efficiencies and would lessen the anticipated forthcoming legislative burden on the Assembly towards the end of this mandate. However, the Committee is conscious that the progress of a Bill on an Independent Statutory Body is not within its control. If it appears that there would be delays in introducing such a Bill then the Committee would seek to progress its own Committee Bill. It is therefore recommended that the Assembly pass a Bill to create a statutory Assembly Commissioner for Standards during this current mandate. It is also recommended that Standing Orders be amended in order to enable the implementation of the conclusions and recommendations of this report.

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

of the Committee relating

to the Report

Wednesday, 14th October 2009

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Francie Brolly

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Trevor Clarke

Rev Robert Coulter

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Miss Grace Hamilton (Assembly Research) (Item 6)

Mr Gerard Rosato (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

2.00 pm The meeting commenced in open session.

5. Consider and agree terms of reference for the Committee Inquiry on enforcing the Code and Guide and appointing a Commissioner for Standards

2.04 pm Mr Ross joined the meeting.

Agreed: Following discussion the Committee agreed the draft Terms of Reference as set out in the Clerk’s paper, as amended. The Committee also agreed that a Public Notice should be issued.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 9th December 2009

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Francie Brolly

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Tara McKee (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Rev Robert Coulter

Mr Paul Maskey

1.20 pm The meeting commenced in public session.

5. Update on Inquiry on the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

The Committee considered an update report and forward work plan for its inquiry on the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the way forward for the inquiry as outlined in the update report.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 13th January, 2010

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Miss Danielle Best (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Miss Rae Browne (Assembly Research (Item 5))

Apologies: Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Mr Paul Maskey

Rev Robert Coulter

1.18 pm The meeting commenced in open session.

5. Update on Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

The Committee noted written submissions and correspondence received on the Inquiry.

The Chairperson welcomed Miss Rae Browne, Assembly Research and invited her to present her Research Paper.

Following discussion the Chairperson thanked Miss Browne for her very comprehensive Research Paper and presentation.

Members noted that as part of the consultation process the Committee would travel to Dublin to meet with Dáil Éireann’s Standards in Public Office Commission and the Committee on Members’ Interests. Members were asked to note a provisional date of 3rd February 2010 for the visit.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 27th January, 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Reverend Coulter

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Thomas Buchanan

1.15 pm The meeting commenced in closed session.

8. Analysis of issues emerging from the written evidence on the Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Members noted further written submissions received.

Members noted the issues emerging from written responses to the Inquiry Consultation as outlined in the Clerk’s paper.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to seek legal advice on the issue of an appeals procedure and the impact of placing the Commissioner on a statutory basis in relation to the potential for judicial reviews.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 10th February, 2010

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Reverend Coulter

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

1.19 pm The meeting commenced in open session.

6. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Members noted the Clerk’s Paper and written submissions received.

Evidence Session – The Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards

The Chairperson welcomed Dr Tom Frawley, Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards and Mr John MacQuarrie, Director for Standards and Special Projects, Ombudsman’s Office and invited Dr Frawley to brief the Committee.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Dr Frawley and Mr MacQuarrie for attending the meeting.

1.59 pm Mr Willie Clarke and Mr Maskey left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Clerk should prepare an estimate of the cost involved in setting up an independent Assembly Commissioner’s office.

2.00 pm Mr Savage left the meeting.

Evidence Session – The Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland

The Chairperson welcomed Ms Felicity Huston, The Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland and invited her to brief the Committee.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Ms Huston for attending the meeting.

Evidence Session – Mr Jeff Cuthbert AM, Chairperson, Committee on Standards of Conduct, National Assembly for Wales

The Chairperson welcomed Mr Jeff Cuthbert AM, Chairperson, Committee on Standards of Conduct, National Assembly for Wales and Mr John Grimes, Committee Clerk, and invited Mr Cuthbert to brief the Committee.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Mr Cuthbert once again for travelling to Northern Ireland to attend the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 17th February, 2010

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Trevor Clarke

Reverend Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apology: Allan Bresland

2.00pm The meeting commenced in open session.

5. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Members noted the Clerk’s Paper and written submissions received.

Evidence Session – Sir Christopher Kelly, Chairman, Committee on Standards in Public Life

The Chairperson welcomed Sir Christopher Kelly, Chairman, Committee on Standards in Public Life who was accompanied by Mr Peter Hawthorne, Assistant Secretary, Committee on Standards in Public Life and invited Sir Christopher to brief the Committee.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Sir Christopher once again for travelling to Northern Ireland to attend the meeting.

Evidence Session – Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission

The Chairperson welcomed Mr Ciarán O Maolain, Head of Legal Services; and Ms Angela Stevens, Caseworker, Legal Services, Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and invited Mr O Maolain to brief the meeting.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Mr O Maolain and Ms Stevens for attending the meeting.

Agreed: Members agreed the draft press release for issue.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 24th February, 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Trevor Clarke

Reverend Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Trevor Reaney (Clerk/Director General) (Item 5)

Mr Tony Logue (Clerk to the Assembly Commission) (Item 5)

Ms Tara Caul (Senior Legal Adviser) (Item 6)

Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Allan Bresland

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr George Savage

1.15pm The meeting commenced in open session.

5. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards: Advice from the Clerk/Director General

Members noted the Clerk’s Paper.

The Chairperson welcomed Mr Trevor Reaney, Clerk/Director General and Mr Tony Logue, Clerk to the Commission and invited Mr Reaney to address the Committee.

1.21pm Mr Ross left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Clerk/Director General should submit a Paper to the Committee on the issues raised in his Advice.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Mr Reaney for his Advice.

1.56pm The Committee moved into closed session.

6. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards: Legal Advice

Members noted the Paper from Legal Services.

The Chairperson welcomed Ms Tara Caul, Senior Legal Adviser, Assembly Legal Services and invited her to present the Legal Paper.

Following a question and answer session the Chairperson thanked Ms Caul for attending.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 10th March, 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr George Savage

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Thomas Buchanan

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Brian Wilson

1.16pm The meeting commenced in open session.

1.28pm The Committee moved into closed session.

7. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

The Committee noted the Clerk’s Paper.

1.50pm Mr Maskey joined the meeting.

Agreed: Following discussion the Committee agreed a number of issues, as set out in the clerk’s memo to Members dated 16th March 2010.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that further consideration should be given to the issues raised in paragraphs 19 - 23 and paragraphs 24 – 28 of the Clerk’s Paper. The Committee agreed that further advice would be helpful and that a briefing note on these issues should be sent to Members and copied to Party Whips.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 24th March, 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Jonathan McMillen (Assistant Legal Adviser) (Items 5 and 7)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Paul Maskey

1.15pm The meeting commenced in closed session.

5. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Members noted the Clerk’s Memo and a further paper including legal advice.

1.25pm Mr Wilson joined the meeting.

The Chairperson welcomed Mr Jonathan McMillen, Assistant Legal Adviser and invited him to brief the Committee on the Legal Advice received.

Agreed: Following discussion it was agreed that the issues raised would be considered further at the next meeting of the Committee.

The Chairperson thanked Mr McMillen.

Members noted correspondence received from the Director General on behalf of the Assembly Commission.

[EXTRACT]

Tuesday, 20th April 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Thomas Buchanan

10.33am The meeting commenced in closed session.

5. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Agreed: Members were updated on the current position on the inquiry. Following discussion on the outstanding issues, the Committee agreed to consider a paper on independent lay members at its next meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Monday, 17th May 2010

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Trevor Clarke

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Rae Browne (Assembly Research Services) (Item 8)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

4.15pm The meeting commenced in closed session.

8. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Members noted the Clerk’s Paper and the Assembly Research Paper on independent lay members.

The Chairperson invited Ms Rae Browne, Assembly Research Services to present her research paper.

Following discussion the Chairperson thanked Ms Browne for attending.

Members noted correspondence from the Assembly Ombudsman.

4.56pm Mr Thomas Buchanan joined the meeting.

Agreed: Following discussion on the issue of independent lay members the Committee agreed that the Clerk should re-draft the relevant paragraphs in the draft Committee Report for consideration by the Committee at its next meeting.

Agreed: Members agreed that the Committee should meet on Tuesday 18th May 2010 to consider the re-drafted sections of the draft Committee Report.

5.04pm Mr Trevor Clarke left the meeting.

The Committee considered the draft Report section by section.

Agreed: All the following sections were agreed with the proviso that Members could raise any issues before final agreement at the next meeting.

Powers and Membership and Table of contents

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Committee Powers and Membership and Table of Contents should form part of the Report.

Introduction

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 1 - 6 should form part of the Report.

Terms of Reference

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 7 should form part of the Report.

Conduct of the Inquiry

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 8 to 10 should form part of the Report.

Modifying and Maintaining the Code of Conduct

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 11 – 14 should form part of the Report.

Handling alleged breaches of the Code of Conduct

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 15 – 18 should form part of the Report.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to carry out an investigation

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 19 - 22 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 23 - 25 should form part of the Report.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to dismiss a complaint

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 26 - 27 should form part of the Report.

Power of the Assembly Commissioner for Standards to recommend a sanction -

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 28 should form part of the Report.

Appeals procedure in relation to decisions reached by the Committee

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 36 - 40 should form part of the Report.

Appointing an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 41 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 42 - 45 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 46 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 47 – 48 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 49 should form part of the Report.

Appointing the Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 50 - 51 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 52 – 53 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 54 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 55 (as amended) – 56 should form part of the Report.

Other issues

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraphs 57 - 58 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 59 should form part of the Report.

[EXTRACT]

Tuesday, 18th May 2010

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mr Trevor Clarke

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Mr Brian Wilson

In Attendance: Mr Paul Gill (Assembly Clerk)

Ms Hilary Bogle (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Michael Greer (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Christopher McNickle (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

10.34am The meeting commenced in closed session.

5. Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards

Agreed: Following discussion the Committee agreed that the outstanding issue in relation to the future composition of the committee as set out in paragraphs 29 to 34, of the draft Report, as amended, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that paragraph 554of the draft Report, as amended, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee was content that the remaining sections of the Report as agreed at the last meeting should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Executive Summary, as amended, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Summary of Recommendations, as amended, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed Appendices 1 – 4 should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the relevant extract of the minutes of the previous meeting and an extract of today’s minutes of proceedings should be included in Appendix 1 of the report.

The Committee ordered the Report on the Committee’s Inquiry on enforcing the Code of Conduct and Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members and the appointment of an Assembly Commissioner for Standards to be printed.

Members noted that the Report would be embargoed until the commencement of the debate in plenary.

Agreed: The Committee agreed a motion to debate the Report in plenary.

Agreed: Members agreed the draft Press Release, as amended, to be released following the debate of the Committee’s Report in plenary.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that an embargoed copy of the report be sent to each of the witnesses who gave oral evidence: Dr Tom Frawley (Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards); Ms Felicity Huston (Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland; Mr Jeff Cuthbert (Chairperson, Committee on Standards of Conduct, National Assembly for Wales); Sir Christopher Kelly (Chairperson, Committee on Standards in Public Life); Mr Ciarán O Maolain (Head of Legal Services) and Ms Angela Stevens (Caseworker, Legal Services), Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

10 February 2010

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Declan O’Loan (Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Billy Leonard

Mr Paul Maskey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr George Savage

Witnesses:

|

Dr Tom Frawley |

Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards Northern Ireland Ombudsman’s Office |

|

Ms Felicity Huston |

Commissioner for Public Appointments Northern Ireland |

|

Mr Jeff Cuthbert |

National Assembly |

1. The Chairperson (Mr O’Loan): We move to our first evidence session with Dr Tom Frawley, who is the Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards. He is accompanied by Mr John MacQuarrie, who is director for standards and special projects at the Ombudsman’s office. Tom and John, you are very welcome and thank you for attending. You have already submitted written evidence and I thank you for it.

2. Members will find the full submission from the Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards in the submissions folder. Tom has been our Interim Commissioner for many years, and he is in a unique position to give evidence to this inquiry. Members will have read Tom’s submission and will know that it touches on a number of areas. In particular, it looks at three different models that the Committee might consider when it comes to appointing a commissioner.

3. Tom, please give us a preliminary outline, then members may have some questions for you. Members, I draw your attention to some possible useful areas of discussion with all of today’s witnesses.

4. Dr Tom Frawley (Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards): I thank the Committee for inviting me to contribute to its inquiry on the appointment of an Assembly commissioner for standards, on maintaining the Northern Ireland Assembly code of conduct, on the ‘Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members’ and on the handling of alleged breaches of the code of conduct.