| Homepage > The Work of the Assembly > Committees > Regional Development > Reports > Report on the Committee's Inquiry into Sustainable Transport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discussion Groups | Thematic Area | Organisations | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Group 1 | Social Aspects | 17 |

18 |

| Working Group 2 | Economic Aspects | 14 |

14 |

| Working Group 3 | Environmental Aspects | 14 |

16 |

| Working Group 4 | Policies | 22 |

24 |

| Working Group 5 | Attitudes | 13 |

13 |

| Working Group 6 | Technologies | 11 |

12 |

52. Details of the names of the organisations and the participants can be found in Appendix 9. Working Group 1 and Working Group 4 were each divided up into two subgroups to ensure that the maximum participant number in group discussions did not exceed 15. One participant moved between groups in both sessions.

53. Copies of the questions to be addressed in each working group, a list of participants in the working groups, and copies of the written submissions received were made available to participants in advance of the evidence engagement event. Working group materials can also be found in Appendix 9.

54. Working groups were facilitated by a member of the Assembly's Research and Library Services. Committee Members were free to join working groups in the role of a silent observer for all or part of any given workshop. Each working group identified one of its number to act as rapporteur on the outcome of their group's discussions to the plenary sessions. After the rapporteurs' feedback, individual participants had an opportunity to voice any other points they wished to raise.

55. Members considered a report on the evidence engagement event at the meeting of 2 June 2010, and agreed draft heads of report of the inquiry, together with outline conclusions and recommendations at a number of meetings in June 2010.

56. In addition to the specific written and oral inquiry evidence received, over the course of the inquiry the Committee also commissioned research papers, from the Assembly's Research Service, and included oral and written evidence and information received during the normal course of the Committee's business which Members thought directly or indirectly had relevance to inquiry. Where appropriate, these are reflected in this report.

57. It is the Committee's view that the time is ripe to move towards more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland. The revised Regional Development Strategy and the Regional Transportation Strategy have both been issued for consultation, and together with the recently completed review of public transport and Transport Act, and the development of rapid transit for Belfast all represent opportunities to stimulate the debate on sustainable transport and to take the actions needed to achieve a modal shift in transport in Northern Ireland. It is to this debate that the Committee wishes to contribute in publishing this report.

58. The terms of reference for this inquiry were wide ranging. The scope of the terms of reference, together with the full programme of legislative, financial and pre-legislative scrutiny as reflected in the Committee's forward work programme, meant that it would not be feasible for the Committee to engage in detailed "drill down" deliberation and exploration of all aspects of the diverse and complex evidence received in the course of the inquiry.

59. For these reasons, and reflecting the Committee's desire to put the issue of sustainable transport onto the agenda for discussion and action, at the meeting of 30 June 2011, Members agreed the key issues it wished to see in its final report.

60. During the finalisation and publication of this report, work has been ongoing on the budget for Northern Ireland for the period 2011 - 2015. The public expenditure context in Northern Ireland, Great Britain, and indeed across the global economy has changed. The Executive is moving from a period of previously stable and steady growth in the economy and in levels of public expenditures into a more uncertain economic and public expenditure environment. The Committee is acutely aware of the profoundly challenging scale and scope of savings to be delivered, and this is reflected in the conclusions and recommendations reached in this report.

61. The Committee agreed its final report on 21 March 2011, and the remainder of this report is structured as follows. The following section sets out what the Committee understands sustainable transport to be, encompassing the relationship between transport and economic, environmental and social sustainability. This is followed by a short section setting out the challenge of sustainable transport in Northern Ireland and includes recently published information on performance against PSA 22 on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the contribution of transport to greenhouse gas emissions in Northern Ireland and forecasts of future levels of transport related greenhouse gas emissions in Northern Ireland. The penultimate section of this report provides an analysis of the written and oral evidence received by the Committee during this inquiry. The final section contains the Committee's conclusions and recommendations on the terms of reference of the inquiry.

62. Appendix 1 contains extracts of the Minutes of Proceedings relating to the Committee's deliberations on the Inquiry. The Minutes of Evidence (Hansard) from the Sustainable Transport Inquiry of 18 March 2010 are at Appendix 2. Written submissions received by the Committee are at Appendix 3. Appendices 4 and 5 contain memoranda and papers from the Department for Regional Development and from others, respectively. The research papers provided by the Assembly's Research and Library Service can be found at Appendix 6. The Evidence Matrix identifying the key themes in the written submissions is included at Appendix 7 and Appendix 8 contains reviews of the written evidence received. Finally, Appendix 9 contains other documents relevant to the inquiry, including information about the oral evidence event working groups.

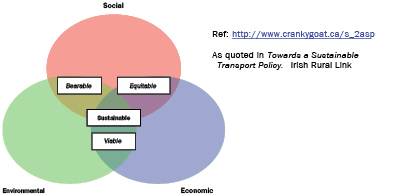

63. This section explores the different aspects of sustainable transport and sets out the Regional Development Committee's approach to sustainable transport as encompassing the established social, environmental and economic benefits that come from adopting a sustainable approach to transport.

64. Sustainability does not focus solely on environmental issues. The notion of policy making which provides an enduring solution to policy area issues is central to the concept of sustainability. World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) speaks of sustainable development policy as something which "… meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".

65. Academics reiterate this endurance dimension, but include the notions of fairness and balance, stating "Sustainability is equity and harmony extended into the future, a careful journey without an endpoint, a continuous striving for the harmonious co-evolution of environmental, economic and socio-cultural goals." (Mega and Pedersen, 1998)

66. Sustainable Transport is a specialist area of sustainability policy making. It has often been defined in terms of its beneficial enabling dimensions. The European Conference of Ministers of Transport 2004 definition speaks of a policy which:

67. The goals of sustainable transport have been defined as ensuring "that environment, social and economic considerations are factored into decisions affecting transportation activity" (Most 1999).

68. Transport plays a part in three of the five principles for sustainable development, as agreed by the UK Government and the Devolved Administrations.[4] The relationship between transport and economic, environmental and social sustainability is explored below. This section of the Committee's report focuses on a number of key reports and studies. It also substantially draws on papers provided by the Assembly's Research and Library Service.

69. Turning first to economic sustainability, the UK principles for Sustainable Development encapsulate this as achieving a sustainable economy. This means building a strong, stable and sustainable economy, which provides prosperity and opportunities for all, in which environmental and social costs fall on those who impose them (sometimes called the polluter pays principle), and efficient resource use is incentivised.

70. The 2006 Eddington Transport Study[5] was commissioned by the UK Government (the Treasury and DfT) to advise the UK Government on long-term links between transport and the productivity, growth and stability of the UK economy, in the context of UK Government commitment to sustainable development. The UK Government agreed with Eddington's analysis, and committed to reviewing its transport strategy, policy and delivery as a result of the advice given by Eddington and by Stern (on the Economics of Climate Change).

71. The conclusions in Eddington's report also appeared to chime with the submissions of key business stakeholders, such as the Confederation of British Industry and the Institute of Directors. Eddington reported that:

72. Eliminating existing congestion on UK roads could save £7-8bn of GDP per year, in Eddington's view. He also reported that the rising costs of congestion could waste £22bn worth of time in England alone by 2025, while a reduction in travel time for UK business of 5% could save £2.5bn of business costs, or 0.2% of GDP.

73. This report further illustrated this issue and suggested that inward investors in London, for example, view the quality of its international connections and domestic networks as a key element of its locational advantage. In his view, this is threatened, by rapidly rising demand on travel systems, densely concentrated on certain parts of the networks at certain times of day, and putting parts of the system under serious strain. To address these problems, Eddington suggested that the key economic challenge is to improve the performance of the existing network, and advised that Government should prioritise action on those parts of the system where networks are critical in supporting economic growth, and there are clear signals that such networks are not performing.

74. Eddington identified a sophisticated policy mix to respond to these challenges. In summary, these are:

75. Finally, Eddington recommended that the strategic economic priorities for long-term transport policy should lie where transport constraints have significant potential to hold back economic growth: in the growing and congested urban areas and their catchments; key inter-urban corridors; and key international gateways that are showing signs of increasing congestion and unreliability.

76. IPPR[6], an independent think-tank, concurred with Eddington's report on the links between transport and national productivity, and, in particular, on the inherent relationship between maximising the economic benefits of density and improving the transport system. IPPR suggested that:

77. If UK policy, as informed by Eddington, was translated into the Northern Ireland context, it might suggest concentrating transport investment in Northern Ireland into the Belfast Metropolitan Area and key strategic routes, to maximise economic returns. This would, of course, need to be balanced by consideration of important environmental and social issues, including climate change and inclusion/equality of opportunity.[7]

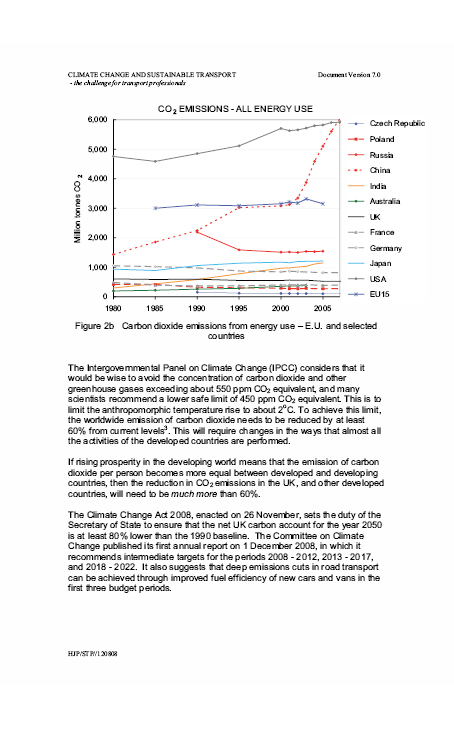

78. The 2006 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change[8] was commissioned by the UK Government (the Treasury) to deliver evidence on the economic impacts of climate change, the economics of stabilising greenhouse gas emissions, and the complex policy challenges in making the transition to a low-carbon economy and ensuring adaptation to the unavoidable consequences of climate change. Stern concluded that:

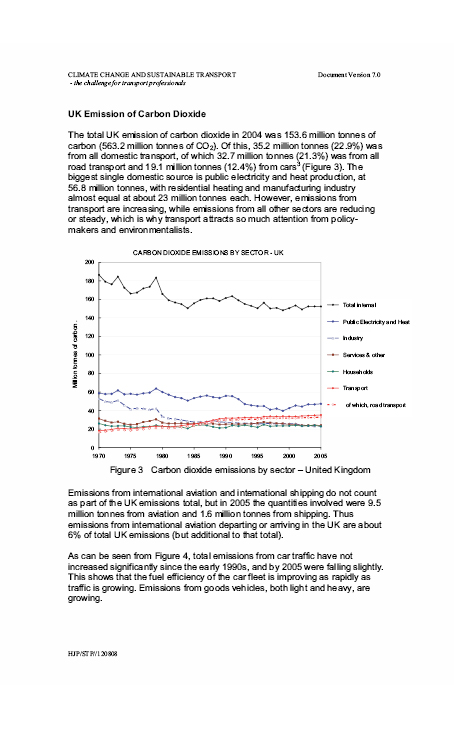

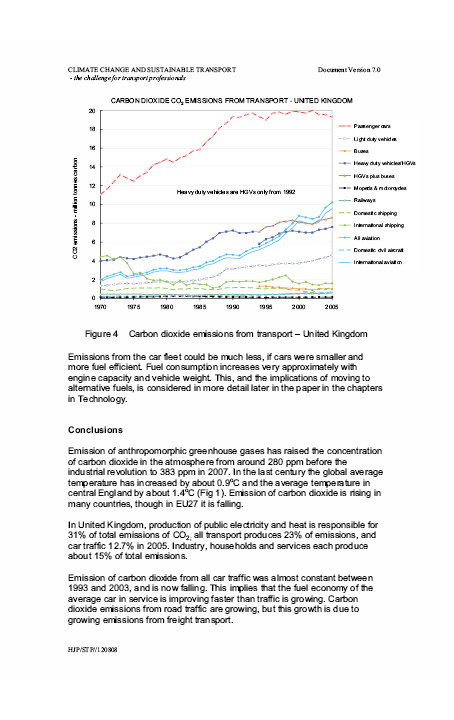

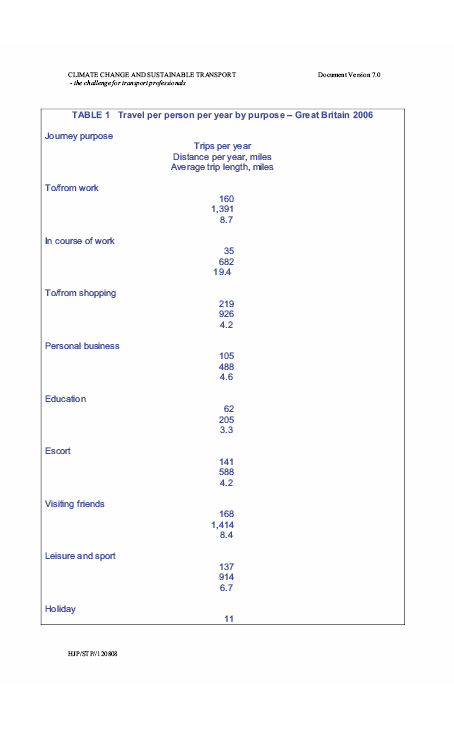

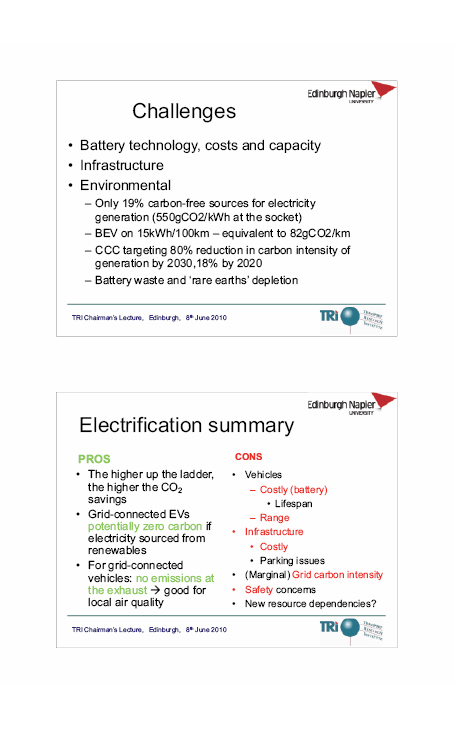

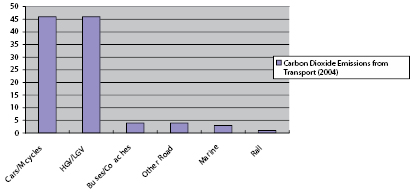

79. Stern reported that transport accounts for 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions and the majority of transport emissions come from road transport and aviation (76% and 12% respectively). This is less than the power and land use sectors, and the same as the agriculture sector. Transport also contributes to climate change in other ways, for example upstream CO2 emissions, where the refineries that produce transport fuel release CO2 emissions, and the electricity consumed by electric trains and road vehicles is indirectly associated with CO2 emissions from the power sector.

80. Transport was the fastest growing sector in OECD countries, and the second fastest growing sector in non-OECD countries between 1990 and 2002, with emissions increasing by 25% and 36% respectively, as reported by Stern. He found that between 2005 and 2050, emissions are expected to grow fastest from aviation (tripling over the period, compared to a doubling of road transport emissions). By 2050, emissions from aviation are expected to account for 2.5% of global GHG emissions.

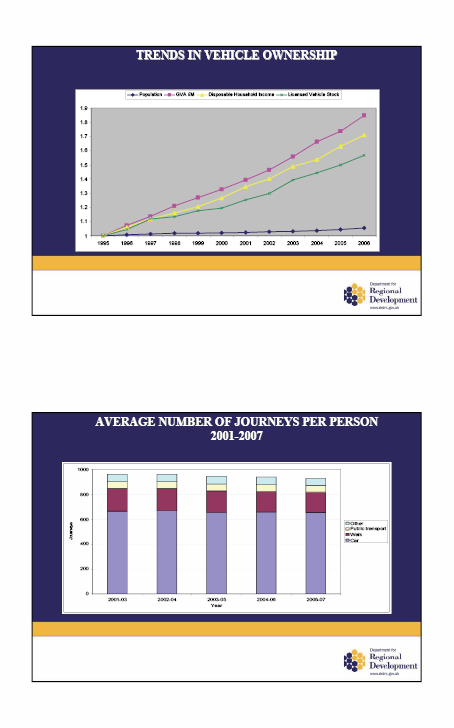

81. Of particular interest to policy makers is Stern reported that demand for transport is a derived demand: it is not demanded for its own sake, but rather for the things it enables people to do, such as get to work, take leisure trips, and move goods from one place to another. He reported that growth in transport emissions is driven by:

82. Stern also expects transport to be among the last sectors to bring emissions down below current levels. He explains that transport is one of the more expensive sectors in which to cut emissions, because the low carbon technologies tend to be expensive and the welfare costs of reducing demand for travel are high. In addition, he expected that transport was likely to be one of the fastest growing sectors in the future.

83. In assessing the prospect for decarbonisation, Stern suggested that road transport was likely to be decarbonised before aviation, and rail could be decarbonised by electrifying the service and generating the electricity in a renewable way.

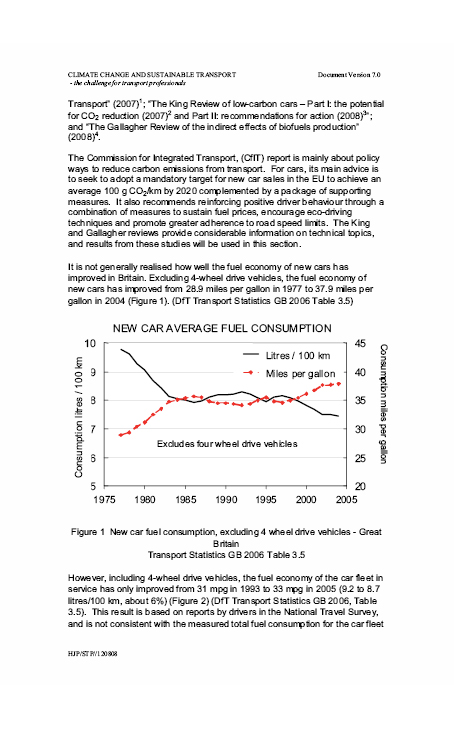

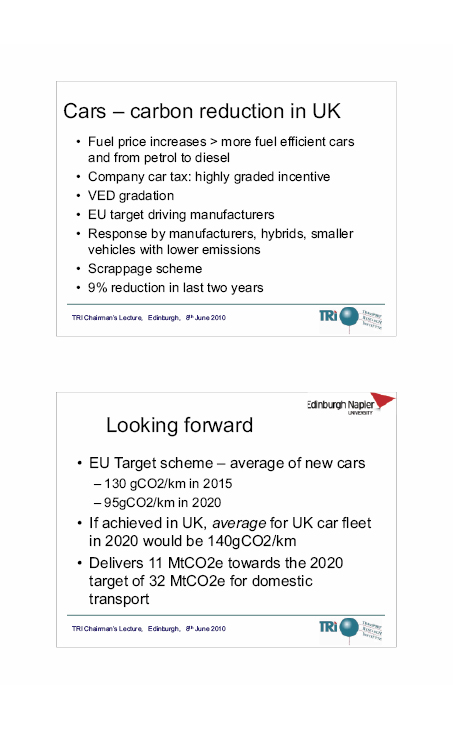

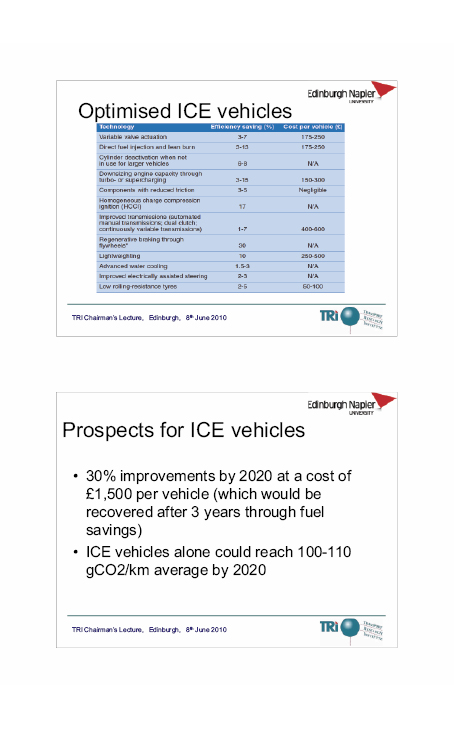

84. Turing to decarbonisation and carbon reduction, the 2008 King Review of Low-Carbon Cars[9] was commissioned by the UK Government (the Treasury and DfT) to independently review and examine the vehicle and fuel technologies which, over the next 25 years, could help to de-carbonise road transport, particularly cars. King concluded that:

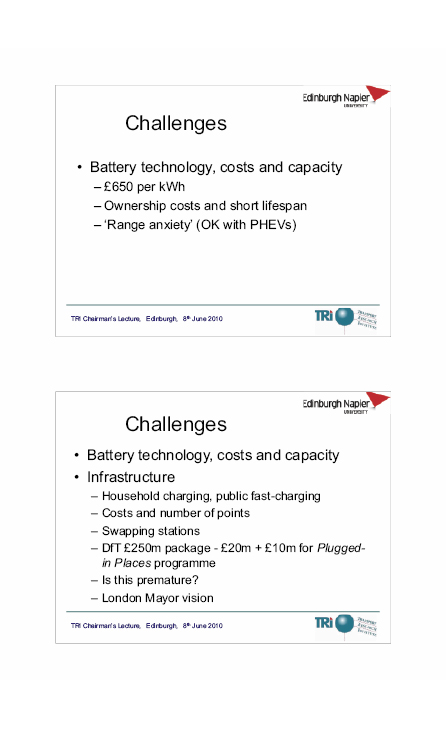

85. To achieve this, King suggested that substantial progress is needed on cleaner fuels, more efficient vehicles and smarter driver choices. King stated that in the long term, carbon-free road transport fuel is the only way to achieve de-carbonisation (essentially 80-90% reduction in emissions). Given supply constraints on bio-fuels, this will require a form of electric vehicle, with novel batteries, charged by 'zero-carbon' electricity. Clean cars are dependent on clean power, so de-carbonisation of road transport will require de-carbonisation of power generation. It will also require more efficient vehicles and in King's view considerable savings can be achieved through technological enhancements to conventional vehicles, in the short term.

86. Finally, King recommended that consumers must be engaged in order to reduce substantially CO2 from road transport. Savings of around 10-15% could come from consumer behaviour by reducing emissions, congestion, and the amount spent on fuel by: demanding new technologies; making the most of technologies and simple aspects of driver efficiency; and small reductions from avoiding low-value journeys, use of alternative means of transport, and more car sharing.

87. Of interest to policy makers is that King noted that environmental awareness and action in road transport tend to lag behind other sectors, and people tend to discount heavily, or ignore, future cost savings from fuel economy when buying a car, even though it is in their own interests. Finally, King suggested that consumer choices can be more directly influenced at a national or local level.

88. The Social Exclusion Unit of the Cabinet Office[10] describes social exclusion as a complex and multi-dimensional situation which:

89. Transport can be a major influence on all of these. According to the Eddington Transport Study[11] for the Treasury and DfT, transport is one of several factors influencing the decision of many people to work or not. This arises because transport costs can represent a much larger share of the income of lower income groups, and it may be these groups where the impacts of transport policy may be perceived as greatest. Therefore Transport interventions can play an important role in supporting the matching of people and skills to jobs. Transport improvements can also limit housing options for lower-paid workers, by encouraging increases in house prices and rents in an area, meaning that such groups can no longer afford to live in areas closer to work, have to move further away, and face the problems of transport costs described above.

90. Eddington also reported that the coordination of transport policy with housing policy can be extremely valuable, therefore, in securing GDP benefits and promoting social inclusion. Quality of life and non-work/leisure travel options are important considerations in influencing location choices in a world where labour, capital and business are all mobile, and transport provision may improve the desirability of urban areas and their catchments to potential incoming migrant workers and foreign investors.

91. The DfT considers the term 'transport poverty' to be useful as a label for the conjunction of certain transport-related problems. The term is not universally agreed, but refers, in broad terms, to the cumulative effect of poor public transport services, poor provision for walking and cycling, and low levels of car ownership, particularly affecting women, the poor, the disabled, dwellers in rural areas and other classically disadvantaged groups. The DfT outlines the ways in which people are excluded[12]:

92. The DfT's work resonates with the Eddington Transport Study, concluding that inadequacies in transport provision may create barriers to social inclusion. The transport system may generate environmental and social costs that bear disproportionately on certain individuals and groups, and transport provision can potentially play an important role in influencing many of the outcomes of social exclusion.

93. Sustrans, the sustainable transport campaign and advisory organisation, believes that the millions of people in the UK who do not have a car, or struggle to afford one, in our 'must-have-car' society, suffer 'transport injustice'[13]. Examples of 'transport injustice' include: difficulties accessing work and other opportunities; enforced indebtedness; reduced opportunity to lead an active healthy life; and, ironically, proportionately greater exposure than average to pollution, road danger and noise caused by those who do have a car. It is important to note that this 'transport injustice' could spread further through society, if oil prices continue to rise and our society continues to be shaped on the assumption that we can all 'hop in the car'.

94. Sustrans sees the steps required to make our transport system 'socially-just' are the same steps needed to make the transport system less carbon-intensive and more robust to oil price shocks:

95. Sustrans considers the measures needed to tackle 'transport injustice' to be small-scale, affordable and excellent value for money. An additional annual spend of just £40 per citizen on such measures would have a major impact, be modest in comparison with current spending on roads, and achieve a socially-just transport system for less than current transport expenditure.

96. The NHS is clear that transport and health are inextricably linked, that transport has major health impacts, and that there are significant inequalities in the impact of transport on the health of individuals and communities[14]. Transport issues are integral to a range of NHS aims and health issues, including physical activity. The Chief Medical Officer of the Department for Health noted that 'the scientific evidence is compelling. Physical activity not only contributes to wellbeing, but is also essential for good health.' The clearest evidence of decreases in physical activity over the past 20–30 years comes from changes in travel patterns, where driving has increased and walking and cycling have decreased steadily.

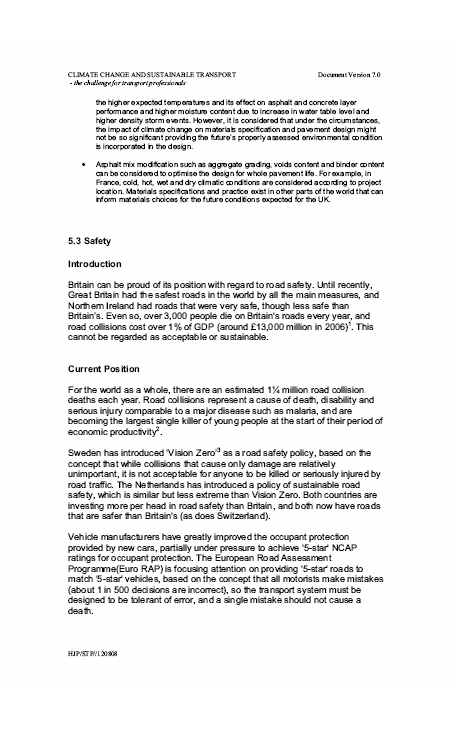

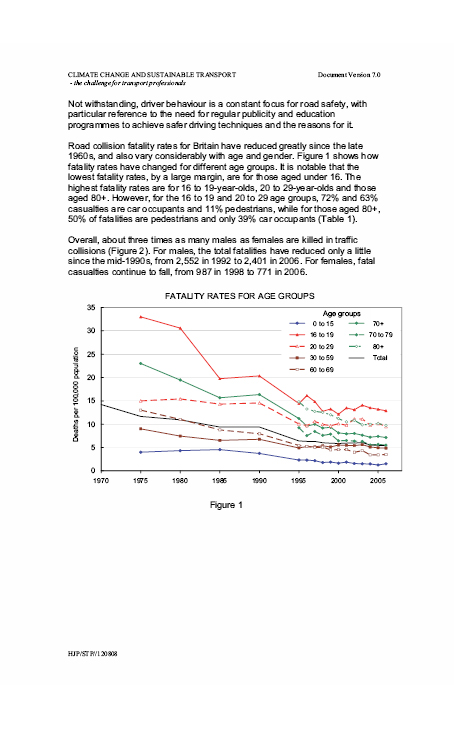

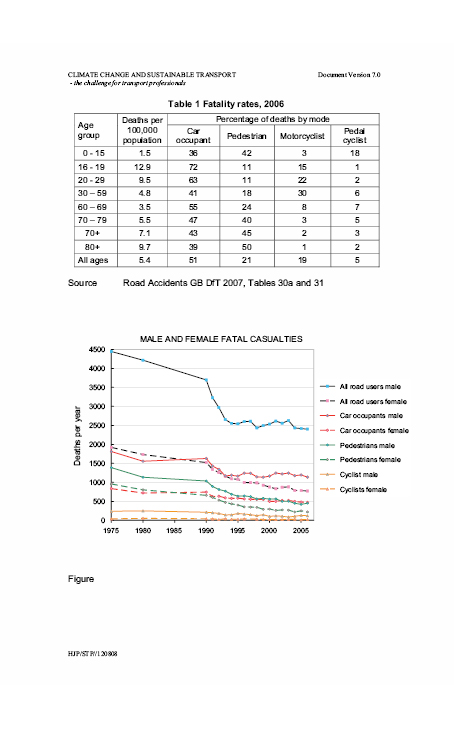

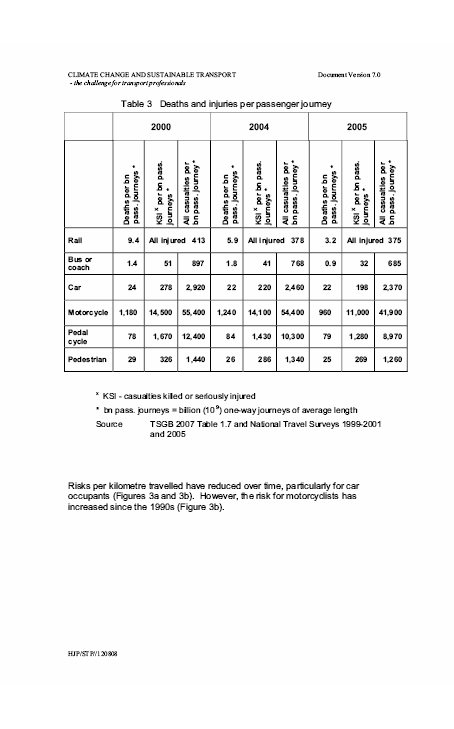

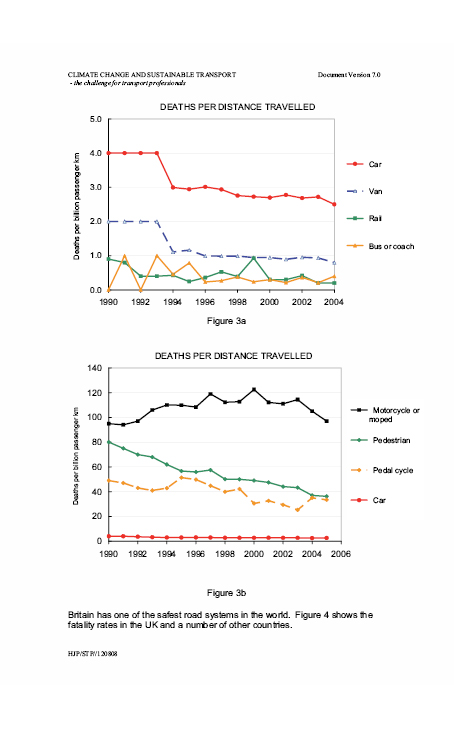

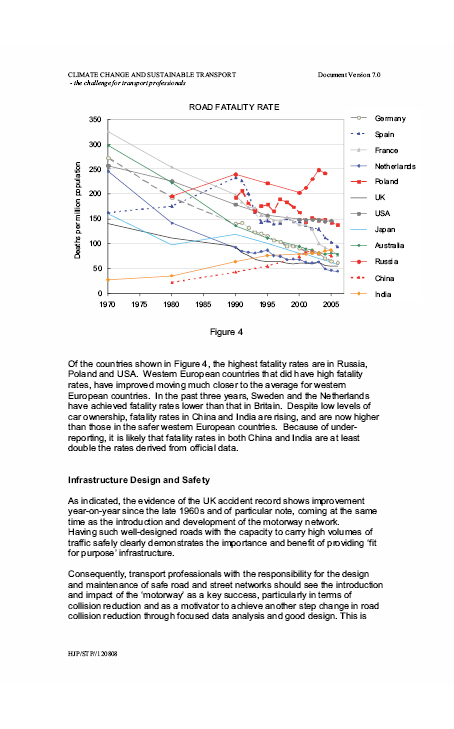

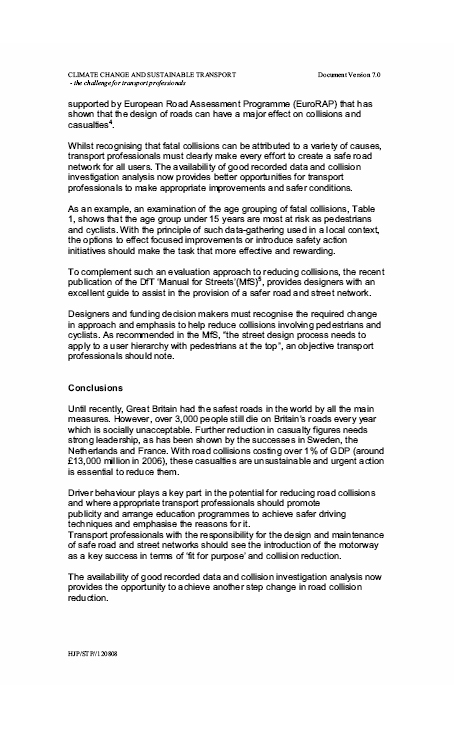

97. Looking now at transport related injuries. In 2007 the total number of road casualties of all severities was 247,000 in Britain (4% lower than in 2006), and 6,300 in Northern Ireland (5% lower than in 2006). 2,700 people were killed on roads in Britain (7% lower than in 2006), and 110 were killed in Northern Ireland (14% lower than in 2006). 27,000 were seriously injured in Britain (3% lower than in 2006), and 1,000 were seriously injured in Northern Ireland (10% lower than in 2006). Finally, 217,000 were slightly injured in Britain (4% lower than in 2006), and 8,500 were slightly injured in Northern Ireland (8% lower than in 2006).

98. Such statistics, while improving, represent a substantial cost to NHS services. The NHS Health Development Agency, in a report on improving health through transport, notes that air pollution is associated with increased mortality and morbidity in both hot and cold weather. The NHS estimates that, each year, 8500 premature deaths in the UK are caused by exposure to particulates, and 3500 premature deaths in the UK are caused by sulphur dioxide. It is thought that exposure to air pollution was worse in areas of greatest disadvantage.

99. The 26% of NI households without access to a car find it harder to travel to get to shops, employment, healthcare and other services. For illustration, the NHS claims that, over a 12 month period in the UK, 1.4 million people miss, turn down or choose not to seek medical help because of transport problems.

100. Studies have demonstrated the links between strong social networks and health: busy roads disrupt social networks and sever communities; and widespread car use results in fewer people interacting on the streets in the ways that pedestrians and cyclists are able to. In addition, ownership/access to a car is highly related to social class. Exposure to air pollution tends to be greater for people experiencing disadvantage, as they are less likely to own a vehicle. Access to healthcare, shops, work and leisure is likely to be more difficult for poorer groups. Children in lower social classes are more likely than those in higher social classes to die as pedestrians.

101. Finally, and illustration of the economic costs of the impact of transport on health includes: £560m from hospital and ambulance costs of injury accidents in GB; and £8.2bn from physical inactivity in England. Economic benefits include have been estimated as £1.3-1.7bn from reductions in particulates, sulphur dioxide and ozone; and £40m from implementation of 110 '20 mph zones' in Kingston-upon-Hull.

102. IPPR[15], the independent think-tank, contends that the car continues to dominate because people have emotional attachments to their cars, there appears to be a rational basis for the car's popularity and there is often a perception, and a reality, that no viable alternative is available. IPPR also notes that congestion is identified by the public as one of the major transport-related problems in Britain, and believes that the public appears to feel that the best way to tackle congestion is by improving public transport.

103. Visible improvements in public transport could increase trust and help persuade people that schemes such as road pricing are not 'just another tax', according to the IPPR. Schemes such as road pricing raise concerns about possible impacts on those with low incomes and those who live in rural areas with limited access to viable alternatives to using cars. Schemes in which revenue is returned, for example through tax cuts or investment in public transport, are found to be more acceptable. Although the idea of a revenue-neutral scheme is more popular than a revenue-raising scheme, it is not known how people reconcile the contradiction of wanting a revenue-neutral scheme at the same time as wanting to hypothecate revenue for public transport. Regardless, transparency in the use of revenue is important.

104. IPPR suggests that a large proportion of the UK population is currently failing to take action to reduce their contribution to climate change, despite high levels of awareness of the problem. It also found that reductions in average emissions from the nation's car fleet are largely driven by technology, not consumer behaviour and few motorists recognise the concept of driving more efficiently.

105. Climate change provides perfect conditions for the 'bystander effect', where there is mass paralysis when people are confronted with a problem but do not act, because they think others should, and will, according to the IPPR. It characterises the two most dominant approaches within the UK dialogue on climate change are the 'alarmists' and the 'small actions'; and finds that this combination is not convincing.

106. The IPPR found that that providing more information about environmental problems has frequently failed to translate into behaviour change. The use of taxes and subsidies to discourage, or encourage, behaviour change has been effective; examples include the switch to unleaded petrol and the London congestion charge. However, its evidence suggests that price signals alone are rarely sufficient; in some cases, because other factors are more influential in determining behaviours than rational calculations about cost, price fails to stimulate behaviour change at all. In response, the IPPR recommends that a policy to reduce car use which takes account of the diverse and complex range of influences on behaviour. Such a policy must include providing convenience; raising understanding; improving the image of alternatives; social proofing; setting attractive rewards and repellent penalties; increasing affordability; and encouraging committing to change.

107. In common with the rest of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the European Union and internationally, the Northern Ireland Executive has signed up to reducing carbon emissions.

108. In addition to a range of environmental Directives and an EU based emissions trading scheme, the EU target is for a reduction of 20% in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2020 on 1990 levels. Commitment has been given that, in the right international conditions, the EU would move to a 30% reduction target. In the United Kingdom, the 2008 Climate Change Act puts into statute the UK's targets to reduce carbon dioxide emissions through domestic and international action by at least 80% by 2050 and at least 34% in the period 2018-2022, against a 1990 baseline. It also includes compliance with a system of five-year carbon budgets, set up to 15 years in advance, to deliver the emission reductions needed to meet the 2022 and 2050 targets. These targets extend to the whole of the UK, and although there is no explicit target or carbon budget for Northern Ireland in the Climate Change Act, Northern Ireland will be expected to play its part in achieving the reductions required.[16]

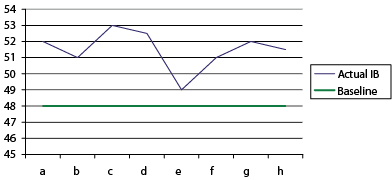

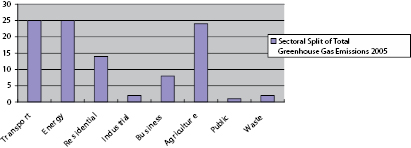

109. In Northern Ireland, Public Service Agreement (PSA) 22 of the current Programme for Government (PfG) has a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25% below 1990 levels by 2025. In February 2011, the Cross- Departmental Working Group on Greenhouse Gas Emissions published the Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Action Plan,[17] setting out how this target reduction will be delivered.

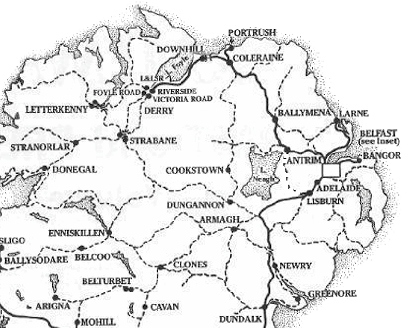

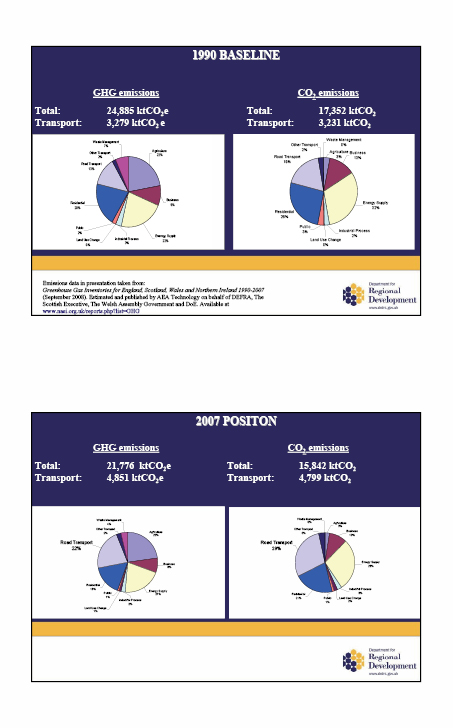

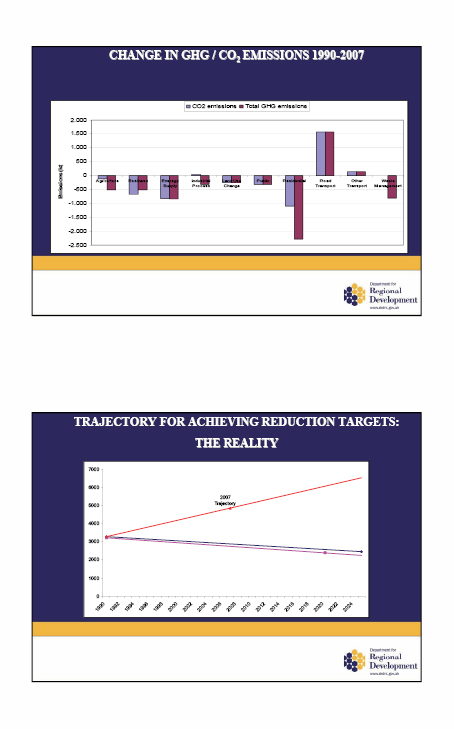

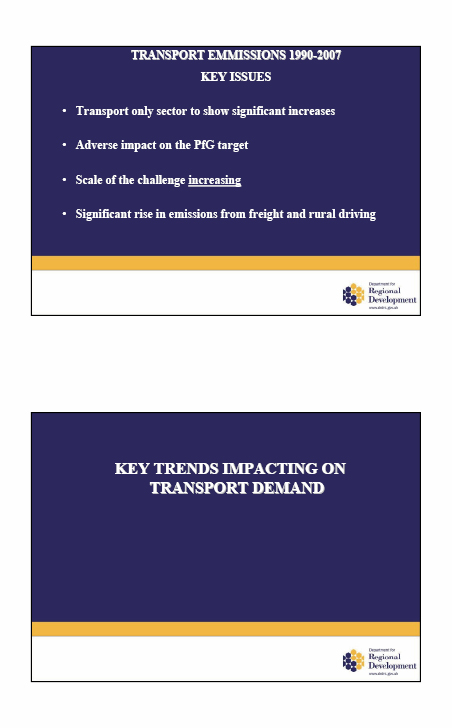

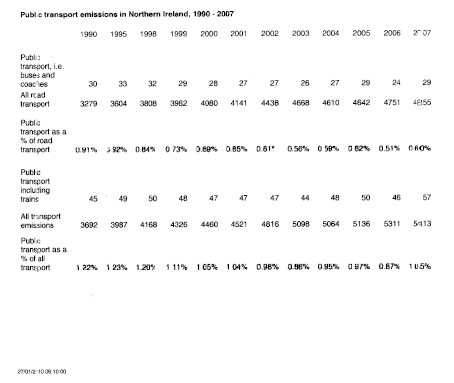

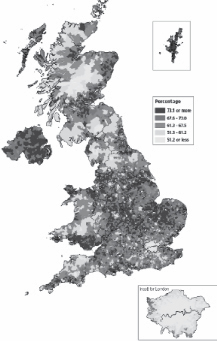

110. The challenge facing Northern Ireland in relation to transport related greenhouse gas emissions is significant. Northern Ireland has a relatively higher level of emissions per capita compared to the UK figure. The reasons for this include high transport emissions due to greater levels of rural driving; greater dependency on oil for home heating systems and the relatively large contribution by agriculture to the economy. The key points to note from the Greenhouse Gas Inventory for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1990-2008 are as follows:

111. The Action Plan by the Cross-Departmental Working Group on Greenhouse Gas Emissions makes clear that;

"Modelling by the CCC (Climate Change Committee) suggests that for the UK to meet the 2020 target, the macroeconomic impact would be less than 1% GDP. The Committee have not attempted to estimate the GDP impact at the level of the national authorities. Nevertheless, both the CCC and the Stern Review agree that the costs of mitigation are substantially lower, and pose less of a threat to economic growth and human welfare, than the damage costs of uncontrolled climate change." (p23)

112. The report also states that although the CCC has not attempted to estimate the impact of carbon budgets on economic growth for the devolved administrations, it finds that there is a relatively small risk to employment and output in Northern Ireland and meeting carbon budgets and emission targets will create job opportunities.[19]

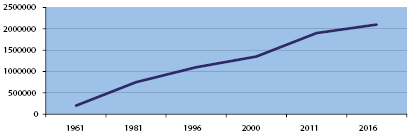

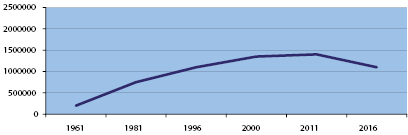

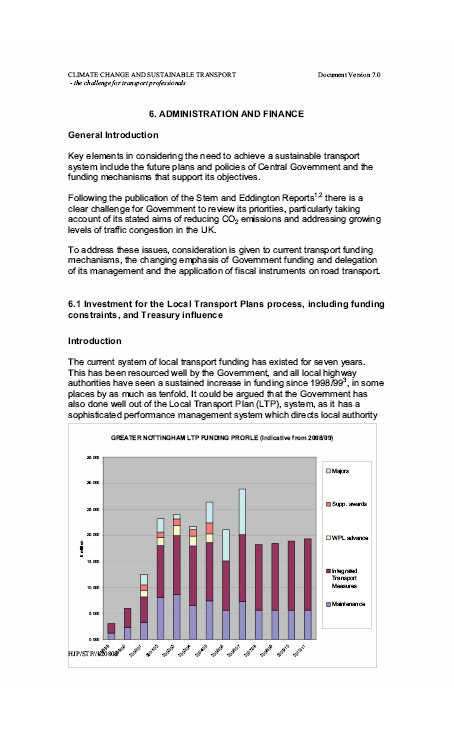

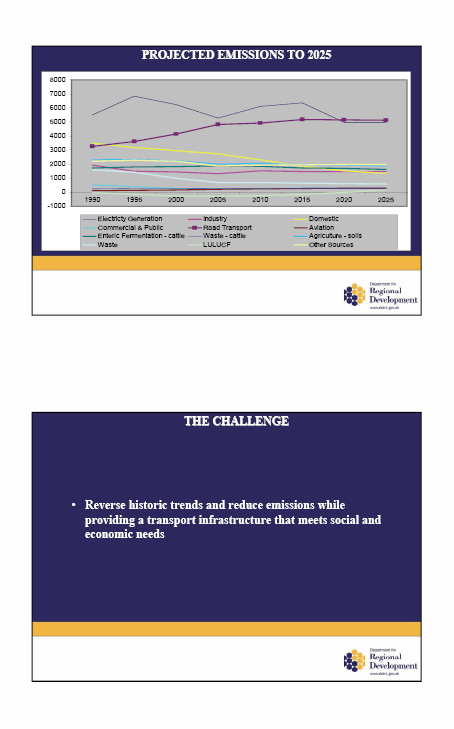

113. Turning now to estimates of future levels of transport related emissions. A number of scenarios have been modelled by the Department and based on the current trend, the results for road transport emissions would be a proportional increase from 13% in 1990 to 20.7% in 2008 to 28.1% in 2025.

114. Two other scenarios are also considered. If road transport emissions follow the short-term historic trends by 2025, emissions are estimated to be 24% higher than in the UK and will account for 31.9% of total Northern Ireland emissions, or a 66.3% increase on the 1990 baseline. If road transport emissions follow the short-term trends to 2015 but level out to 2025 (the +12% scenario) , then road transport related emissions are estimated to account for 29.7% of total Northern Ireland emissions, or a 50.2% increase on the 1990 baseline. It is import to note that this scenario (scenario two) would require significant local policy intervention measures.

115. There are undoubtedly measurement problems identified by the Department in relation to projecting past levels of emissions into the future. The Regional Development Strategy and the Regional Transportation Strategy have both been published for consultation however no costs or benefits can be estimated at this time. The DRD has stated that more comprehensive modelling and research is required, however it will continue to explore how the impacts of policy interventions can be quantified and the estimates for Northern Ireland road transport emissions could be made more robust and Northern Ireland relevant.

116. These are sobering findings. Despite the measurement issues identified by the Department for Regional Development, it is clear that unless serious and urgent action is taken to address transport sector GHG emissions, particularly road transport related emissions, then Northern Ireland's contribution to the overall UK achievement of its reduction targets will be jeopardised. There will also be negative impacts on the efficiency and competitiveness of doing business here, the health and wellbeing of our population, and the vibrancy of our communities.

117. The first element of the Committee's inquiry terms of reference is to explore and clarify the social, environmental and economic aspects of sustainable transport. This section of the Committee's inquiry report presents an overview of the key inquiry issues emerging from the written and oral evidence received by the Committee.

118. In response to the Committee's call for evidence, a total of 24 organizations and individuals submitted written evidence to the Committee's inquiry on sustainable transport. These included academics, transport and planning professionals, government departments, environmental NGOs, transport providers, industry and voluntary and community sector organizations. Responses were also received from the Department of Education, the Enterprise Trade and Investment Committee, the Social Development Committee, the Agriculture and Rural Development Committee and the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

119. Generally speaking, there was a high degree of commonality in the themes and issues identified in the submissions received. The following points provide an overview of the range and depth of information provided. Some of the submissions noted the interdependence and connectedness of the social, environmental and economic sustainability, and many highlighted the health benefits of more active modes of transportation. Increasing emissions from transport, against a backdrop of falling emissions generally, was a feature in many of the submissions, as was the role of road freight in generating emissions.

120. Many of the submissions highlighted the potential of new technologies, electronic and hybrid vehicles powered by renewable energy sources. A rethinking of the use of existing technologies and transport modes was also advocated, as was a greater role for walking and cycling. Many of the submissions recommended the development of specific, and in many cases, legally binding targets for Northern Ireland in areas such as emission reductions, procurement, and policy.

121. A number of submissions contained information which would merit further examination such as tax incentives for employees using public transport to travel to work, and employer sponsored bike to work schemes.

122. The written submission stage produced an extensive bibliography of existing literature from academic, governmental and public and private sector organisations. Whilst the use of case studies, comparative examples and best practice examples are useful per se as an illustrative function to demonstrate the signposts and goal posts for Northern Ireland's Sustainable Transport future, there is a lack of clarity as to the extent of the validity of the comparators in terms of the degree of applicability of illustrative examples to the socio-economic profile and socio-geographic profile of Northern Ireland. Notwithstanding this possible limitation, this information provides signposts to possible solutions to sustainable transport solutions which have been found by policy neighbours. There is merit in the further investigation of whether such comparative and best practices examples can be transferred in whole or tailored to accommodate the individual make-up and needs of Northern Ireland.

123. Similarly, whilst many of the respondees acknowledged both the need for new investment in infrastructures which supports the core components of a sustainable transport strategy and the growing awareness of the implications of the current economic crisis on public sector budgets, none of the submissions specifically identified possible sources of funding for new infrastructures. European engagement was rarely identified as a possible tool of networking, for example in terms of exploring of funding possibilities from the EU.

124. The respondees indicate that the social aspects of sustainable transport are to be found in issues of social equity and inclusion, with particular regard to the distribution of resources, the accessibility of transportation modes, road safety and the ability to utilise the health benefits of walking and cycling. Responses clearly expressed a need for policy making to promote a positive discrimination approach towards public transport, cycling and walking and at the same time to make private car usage an unattractive alternative, in particular the predominant single passenger usage.

125. In terms of environmental issues, the responses identify the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel dependency as key issues, in particular, to be achieved by the reduction of the over-dependency on private car usage in Northern Ireland. This issue is intrinsically linked to an improvement in cycle and pedestrian safety measures to encourage an uptake in non-motorized transportation modes. Further town planning and land planning are named as key policy areas which contribute to the environmental aspects of sustainable transportation. Obesity is identified as a major health concern which could be partially addressed by encouraging walking and cycling.

126. Investment, reward and financial information underline the third subsection, economic aspects of sustainable transport. Respondees highlight sustainability as having real potential as a future growth industry in Northern Ireland. In this context respondees indicate the need for investment into research with cost-benefit analysis outcomes, or revealing "full-external costs" of current town and land planning decision making. Reward aspects are generically concerned with carrot-stick approaches to sustainable transport friendly travel choices. Some respondees highlighted the effectiveness of financial penalties in terms of higher taxation, fees, etc., for non-sustainable transport choices and policy making.

127. The responses received indentified generic policies likely to underpin a move to sustainable transport in Northern Ireland. The focus of the comments received reflects the awareness of the overdependence on private individual car transport in Northern Ireland. Respondees express a need for policy making to promote a positive discrimination approach towards public transport, cycling and walking and at the same time to make private car usage an unattractive alternative, in particular the predominant single passenger usage.

128. Further, many respondees identified a vast span of already existing literature which is deemed relevant to the discussion. Frequent reference was made to the findings of the Stern Review to evidence climate change issues. The scope of the additionally cited sources is vast and included international, European; national and local level research conducted by academics and scientists as well as public sector and private sector bodies which have a particular interest in the theme of sustainability and sustainable transport. The themes addressed in this literature mirror the issues raised in the responses to the Committee and include global environmental issues, urban environment, energy consumption, public transportation, health, cycling, and road safety.

129. In terms of changing mindsets, there was considerable commonality around the need to deliver educational programmes to all members of, and groups within, our society to raise awareness of more individual contributions to the sustainable transport system. Respondees also highlighted the need for employer incentives to reduce individual private car transportation, the desirability of promoting opportunity and innovation in this field, increased awareness of our environmental limits and of the linkage between sustainable transport and healthy living.

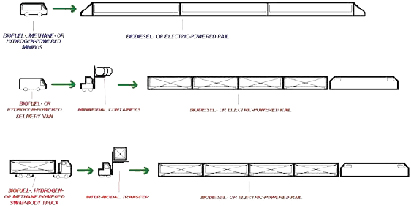

130. Responses, when asked to identify technologies likely to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland highlighted existing public transportation schemes such as Dial-A Lift and the Assisted Rural Transport Scheme as examples of good practice. Reference was also made to new technologies in operation in other cities in the UK and in Europe. The proposed bus-based rapid transport system for Belfast was named as forward-looking expansion on our current public transportation services. The availability of integrated information systems technology was also seen as providing an advance in the customer's experience of public transportation. The freight industry identified double-decker and flexible freight trailer designs as new technological advances which could reduce the overall volume of freight road transportation. The development of new, and the expansion of existing, cycle path networks coupled with improved provision of facilities at workplaces was also highlighted by several respondees.

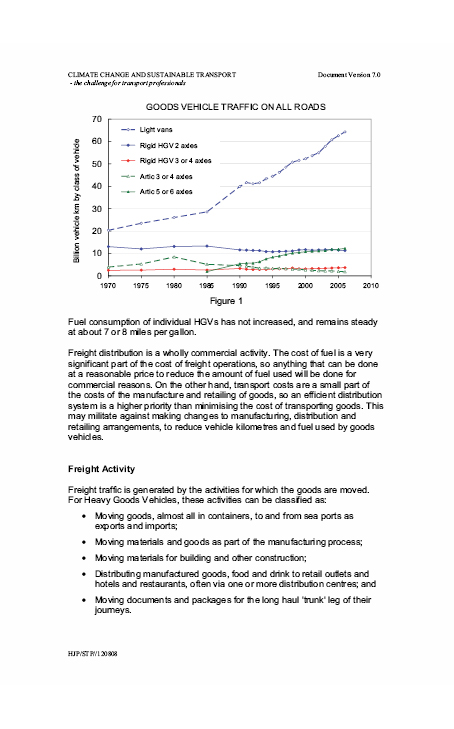

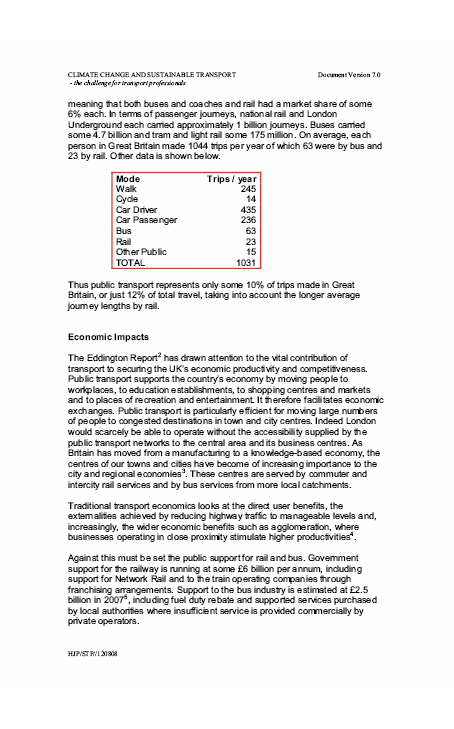

131. Figure 1 below provides an overview of the responses received, by theme.

| Thematic Area | General Issue | Sub Issues | Identified By |

| Modes of Transport | Overdependency of Private Cars | Including Single Car Usage, Emotional Attachement to Cars | Acheson, Bc,Acis, Bmrg, Cilt, Iph, Niel, Sdc, Sustrans, Wwf |

| Externalised Costs | Acheson | ||

| Vehicle Miles Travelled (under 5 miles) | Acheson, SDC, Sustrans | ||

| High Occupancy Vehicle Lanes | British Council, SDC | ||

| Car Clubs | CILT, SDC | ||

| Car Sharing | CILT, SDC | ||

| Car Pooling | CILT, SDC | ||

| Park and Ride Facilities/Walking Facilities | CTA, PGI | ||

| Lower Speed Limits in Residential Areas | NIEL, SDC, Sustrans | ||

| On site car parking | PGI | ||

| Off-site car parking for staff | PGI | ||

| Allocation of Public Sector Jobs (Bain Review) | RCN | ||

| Introduction of congestion charging | SDC | ||

| Current public transportation system | Challenge to Improve Services and Attractiveness | ACIS, PGI | |

| State subsidies for transport links in new developments | BMRG | ||

| Tax effective purchasing of tickets | CTA | ||

| Online purchasing of tickets | CTA | ||

| Review of Bus Corridors in Main Cities | CTA | ||

| Integrated public transport timetabling | CTA, PGI | ||

| Education in schools about public transportation | CTA | ||

| Provision of Enhanced Traffic Management Systems | ACIS, PGI | ||

| Lack of coordination | PGI | ||

| Underutilization of existing transportation vehciles | RCN, Wilson,, DENI | ||

| Dissemination of information on public transport services | RCN, SDC | ||

| Walking and Cycling | Health and Environmental Benefits | Acheson, BC, BHC, CILT, FotE. Greenway to Stay, IPH, NIEL, RCN, SDC | |

| Road and Pedestrian Safety and Education thereof | Acheson, BHC, FotE, IPH, SDC, Sustrans | ||

| Employer and State Incentives | Acheson, | ||

| Cost-Benefits Analysis | Acheson, | ||

| Cycle Rental Schemes | British Council | ||

| Provision of Hygiene and Changing Facilities | CILT | ||

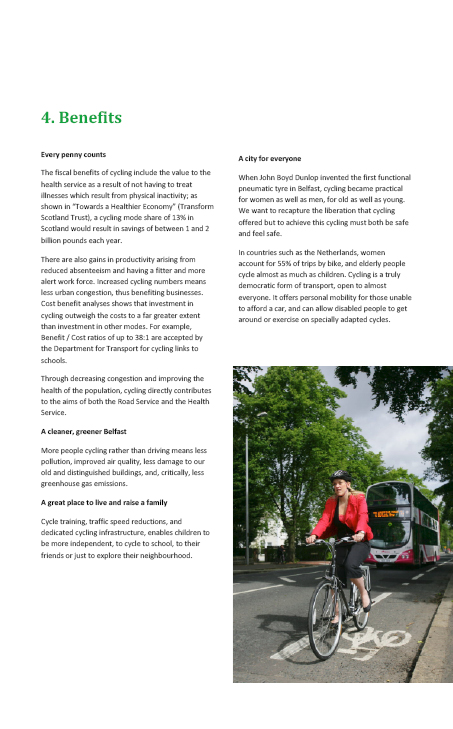

| Reduced Absenteeism and Improved Fitness | FotE, Sustrans | ||

| Greater independence of our children | FotE | ||

| Broad Accessibility | FotE | ||

| Promotional Events | FotE | ||

| Tax-Free Bicycle Purchase Schemes | FotE | ||

| Creation of Walking and Cycling Networks | RCN | ||

| Alternative Modes of Transport | Electric Vehicles, Monorails | BMRG, WWF | |

| Potential of Inland Waterways | CILT | ||

| Bus Rapid Transit (pro) | CILT | ||

| Bus Rapid Transit (anti) | Greenway to Stay | ||

| Door-to-Door | CTA, RCN | ||

| Rail | LLoA, SDC | ||

| Electrification of current and future NI Rail Network | LLoA | ||

| Trams, Quality Bus Corridors | PGI | ||

| School Transport | DENI, RCN | ||

| Social Services Transport | RCN | ||

| Low Carbon Vehicles | SDC, WWF | ||

| Hybrid Vehicles | ETI |

| Thematic Area | General Issue | Sub Issues | Identified By |

| Accessibility and Equality | Social inclusion, including pt service provision | Geographical, Age, Gender, Disability, Economic | A2B, Acheson, BHC, CILT,CTA, IPH, NIEL, PGI, RCN, Sustrans, Wilson |

| Concessions (passes, fuel) | A2B, RCN | ||

| Real Time Passenger Information Technology | ACIS | ||

| Community Engagement | Belfast Healthy Cities | ||

| Disability and Accessibility | Door-to-Door as an interim solution | CTA | |

| Education | Low Education Level of Professional Drivers | CTA | |

| Spatial Planning | Carrot and Stick measures | Parking charges reflecting full external costs | Acheson, NIEL, PGI, WWF |

| Cost-Benefit Methodology of Road Building | Flaws in current weighing systems | Acheson, | |

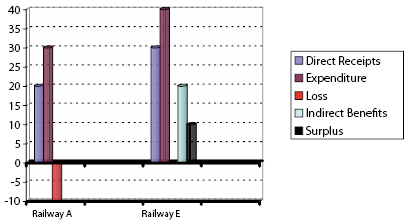

| Cost-Benefit Analysis of Rail Infrastructure | External Benefits of Rail mode | LLoA | |

| Comparative Costs of Cycling and Road Building | Higher comparative cost benefit ratio | Acheson, | |

| Cycle Path infrastructure | Lack of cycle paths, greenway networks, signage | CILT, FotE | |

| Adequate Cycle Access and Storage | Cycle Stands | BMRG | |

| Rail Travel | Less Land Intensive | LLoA | |

| Improved pedestrian access | PGI, SDC | ||

| Enhanced public transport links | NIR/Ulsterbus | PGI, SDC | |

| Employment related planning issues | Flexi-time, home office, audio visual conferences | PGI, SDC, DENI | |

| Integrated system of land use and public transport | No detectable features at present | PGI, RCN, SDC, WWF | |

| Need for Health Impact Assesments | in context of transport and land use decisions | Sustrans | |

| Lack of policy in rural areas | Need for a Rural and Equality Proofing scheme | RCN | |

| Removal of sectarian legacy transport planning | Shift to non-sectarian route planning of buses | Wilson |

| Thematic Area | General Issue | Sub Issues | Identified By |

| Health | Walking and Cycling | See "Modes of Transport" | BHC, IPH, WWF |

| Obesity and the need for Physical Activity | BHC, IPH, Sustrans | ||

| Health Authorities to assess impacts of transport | BHC, FotE, IPH | ||

| Higher health risk to urban dwellers | NIEL | ||

| Environment | Overdependency on fossil fuels | Acheson, EST, NIEL, RCN, SDC, Sustrans, WWF, ETI | |

| Emissions - Greenhouse Gas, Fossil Fuels | BHC, CILT,NIEL, RCN, SDC, Sustrans, WWF, ETI | ||

| Reduction of Air Pollution | BHC, LLoA, NIEL, SDC, WWF | ||

| Tackling Climate Change | BHC, IPH, LLoA, NIEL, SDC, Wilson, WWF, ETI | ||

| Aviation emissions and pollution | CILT, SDC | ||

| Alternative fuel sources | Biofuels, Biogas, Wind Energy, RTFO | CILT, NIEL, SDC, ETI | |

| Incentives to purchase low carbon emission cars | EST, | ||

| Education of public on environmental issues | EST, | ||

| Rail freight as environmentally friendly mode | LLoA | ||

| Attainment of EU policy and directive targets | NIEL, WWF, ETI | ||

| Govt. Investment in Sustainable Transport | Level of allocation too low | NIEL, Sustrans | |

| Mandatory Vehicle Efficiency Improvement | SDC | ||

| Promotion of Home Shopping | Reduction in road usage by private cars | SDC |

132. The second phase of evidence gathering for the inquiry was an oral evidence session at the Long Gallery in Parliament Buildings. The evidence session was divided into two sessions. Participants self selected into one of three working groups in Session One focusing on social, environmental or economic sustainability, and in these groups they were asked to identify and prioritise key aspects of social, environmental or economic sustainability. In Session Two, three working groups were held to identify priorities for action on policies, attitudes and technologies likely to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland.

133. There were three working groups in Session One: Social Aspects, Economic Aspects and Environmental Aspects. The key findings from the working groups 1, 2 and 3 are set out below.

134. Working Group 1, consisting of two subgroups, was asked to explore the following discussion questions:

It is often said that for transport to be sustainable, it must be environmentally, socially and economically sustainable.

What are the 3 most important aspects of social sustainability?

Of these 3 characteristics, which is the single most important?

135. In terms of social aspects of sustainable transport, subgroup 1 produced a non-hierarchical list of three aspects which were deemed to be the most important social aspects of social sustainability. These are:

136. Subgroup 2, which responded to the same questions, similarly produced a non-hierarchical list of the three aspects which were deemed to be the most important social aspects of social sustainability. These are:

137. The broader discussion of social sustainability reiterated issues raised in the written submission stage, as referred to in the opening address. These include:

138. The outcome presentation by the rapporteur of the social aspects working group was expanded by one group member. The focus of this contribution was on the link between achieving social equity through improving infrastructure, in particular through the allocation of road space. Making more road space available to more sustainable modes of transport and less road space to less sustainable may help direct citizens' choices. The impact of high volumes of road on road safety and in restricting use of open spaces to pedestrians and residents of residential areas was also raised.

139. Working Group 2, was asked to explore the following discussion questions:

It is often said that for transport to be sustainable, it must be environmentally, socially and economically sustainable.

What are the 3 most important aspects of economic sustainability?

Of these 3 characteristics, which is the single most important?

140. In terms of the economic aspects of sustainable transport, Working Group 2 did not restrict itself to specifically identify the three most important aspects, but did through qualifiers indicate a non-hierarchical list of aspects which were deemed to be the most important aspects of economic sustainability. These are:

141. The broader discussion of economic sustainability was anchored in the context of "what sustainability meant in relation to living within our means, supporting the ability of future generations to live within their means and consuming at a sustainable rate" (Hansard 18 March 2010). The points raised mirrored the content of the evidence submitted by respondents at the written evidence stage. These included:

142. The rapporteur feedback was expanded by one further contribution which highlighted the need to examine how to internalise the costs of carbon-intensive transport systems which are currently externalised.

143. Working Group 3 was asked to explore the following discussion questions:

It is often said that for transport to be sustainable, it must be environmentally, socially and economically sustainable.

What are the 3 most important aspects of environmental sustainability?

Of these 3 characteristics, which is the single most important?

144. In terms of the environmental aspects of sustainable transport, Working Group 3 produced a non-hierarchical list of three aspects which were deemed to be the most important aspects of environmental sustainability. These are:

145. The broader discussion of environmental sustainability mirrored the content of the evidence submitted by the respondents at the written evidence stage. These included:

146. The rapporteur's presentation of the working group evidence on environmental aspects was not expanded by further plenary contributions by individual working group members.

147. The second session working groups (4,5,6) reflected the thematic areas identified in the inquiry terms of reference, namely, "to identify the policies, attitudes and technologies likely to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland". The overall aim of these working groups was to use the impetus of the session one discussions, where participants had agreed priority areas in each of their specialist thematic areas, as the basis for reflexive discussion of how to move towards a more sustainable transport system in Northern Ireland.

148. The value of the changed composition of earlier working group participants was explicitly commented upon in the plenary session: "The first sessions were fine because we were all in our comfort zones. We were all in our little groups: the social group; the economic group; and the environmental group. However, when we mixed …… we started to see tensions among the various stakeholders."(Hansard 18 March 2010)

149. Working Group 4, consisting of two subgroups, were asked to explore the following discussion questions:

What are the 3 most important policy interventions needed to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

Of these, which is the single most feasible policy action?

In policy terms, what is the greatest opportunity to deliver more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland?

Again, in policy terms, what is the biggest threat to achieving more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

150. In terms of the identification of three most important policy interventions needed to underpin a move to a more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland, subgroup 1 arrived at the following outcome:

151. In response to the second question, the single most feasible policy action, subgroup 1 considered the need for integration to be "the most important"(Hansard 18 March 2010)

152. In response to question three, three types of opportunities were identified:

153. In response to question four, the biggest threats to achieving more sustainable transport, the following threats were identified:

154. In terms of the identification of three most important policy interventions needed to underpin a move to a more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland, subgroup 2 stated the need for policy aims to assist:

155. Subgroup 2 engaged in a broader discussion of policy issues which mirrored the content of the evidence submitted by the respondents at the written evidence stage. The discussion included issues such as:

156. In response to the second question, the single most feasible policy action, subgroup 2 suggested that "investment up front at this stage in transportation development would benefit budgets in the long term." (Hansard 18 March 2010) The group noted that a balance must be found in equitable investment between rural and urban areas.

157. In response to question three, what is the greatest opportunity to deliver more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland, the following opportunities were identified:

158. In response to question four, the biggest threats to achieving more sustainable transport, the indirect responses to this question are to be found in concerns that future transportation development plans may be detrimental to the rural economy. (Hansard 18 March 2010)

159. Working Group 5 was ask to explore the following discussion questions:

What are the 3 most important attitudinal changes needed to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

Of these, which is the single most achievable attitudinal change?

What, in your opinion, is the greatest opportunity to change attitudes in favour of more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland?

What, in your opinion, is the biggest threat to changing attitudes to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

160. In terms of the identification of three most important attitudinal changes needed to underpin a move to a more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland, the following outcome:

161. In response to the second question, the single most achievable attitudinal change was identified as being

162. The broader discussion which resulted in this response covered a range of issues related to:

163. In response to question three, the greatest opportunity to change attitudes in favour of more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland was stated as:

164. In response to question four, the biggest threats to changing attitudes to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland, the following threats were identified:

165. The rapporteur's feedback was expanded by one further contribution which highlighted the usefulness of the Carbon Footprint metric. It was argued that increased awareness amongst the public of this metric would prove beneficial in terms of the government taking the right decisions.

166. Working Group 6 was asked to explore the following discussion questions:

What are the 3 most important technologies to develop/adopt to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

Of these, which is the single most achievable technological change?

In terms of technologies, what is the single opportunity most likely to deliver more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland?

Again in terms of technologies, what is the biggest threat to achieving more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland?

167. In response to the task of identifying the three most important technologies to develop/adopt to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland , working group 6 identified six technologies, namely,

168. In response to the second question, the single most achievable technological change, the group is possibly reflected in its concentration on fuel technology.

169. It is not possible to deduce a clear response to question three (what is the single opportunity most likely to deliver more sustainable public transport in Northern Ireland) from the rapporteur's evidence.

170. In response to question four, the biggest threats to achieving more sustainable transport, the group expressed the view that sustainable transport would not be achieved unless there was a change in people's attitudes and behaviours.

171. Following the Session Two rapporteur presentations, nine further contributions were made to the discussions.

172. Three of the nine individual participants voiced positive comments for the structure of the workshop, which included "congratulations (sic) … for holding the event" and describing the exchange of ideas as being "enlightening to hear alternative views". As previously mentioned, one participant expressed the workshop structure as being "interesting" as it provided an opportunity to discuss issues both with similar minded people where all participants where "in their comfort zone" and in hybrid groups where it was possible to experience "tensions amongst the various stakeholders". (Hansard 18 March 2010)

173. One participation expressed regret that the private sector was underrepresented at the event and specifically noted the absence of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), the Institute of Directors (IoD) and the Northern Ireland Independent Retail Trade Association (NIIRTA).

174. Other participants raised points of information, concerns and comments about a variety of issues including:

175. In terms of leadership by government, the contributors indicated that

176. The Committee recognises that sustainability in transport is not as simple as spending on roads versus spending on public transport, particularly when set against a pattern of dispersed settlement, restricted public expenditures, and the needs of a wide variety of groups. These groups include those for whom private car-based transport is not an option (such as older people, people with disabilities, young people and people without access to a car) as well as rural and urban-based businesses and those without access to viable public transport options.

177. The Committee is keenly aware that sustainable transport may mean different things in urban and rural areas – one policy does not fit all. There are many communities and individuals across Northern Ireland for whom public transport is not a viable option. This may be because services are not available at times or to destinations that suit their needs, or because population density is not high enough to make the provision of public transport services economically sustainable. In such circumstances, reliance on private car use is inevitable and investment in the road network is essential. The Committee is of the view that the challenge is to maximise the numbers moving from private to public transport in situations where public transport is a viable option, and to encourage those for whom public transport is not an option to plug into the public transport network whenever possible.

178. It is the Committee's view that developing truly sustainable transportation in Northern Ireland requires policies to underpin this move. This section includes policy areas within the remit of DRD, and those falling to other Departments, which can be demonstrated to contribute to developing more sustainable transport.

179. The Committee is very concerned by the data on Northern Ireland's past performance, and the modelling data on likely future emissions levels, published by the Cross-Departmental Working Group on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in February 2011. The Committee recommends the immediate review of Public Service Agreement 22 in the Programme for Government, with a view to allocating GHG emission reduction targets to the relevant government departments, including the Department for Regional Development.

180. The Committee noted that the UK level GHG reduction targets have a statutory basis and recommends that the Executive begins a dialogue to explore the implications for Northern Ireland of putting our GHG reduction targets onto a statutory footing. This dialogue should include government departments and the wider public sector, key stakeholders, representatives of business and industry, expert academics and scientists and other relevant stakeholders.

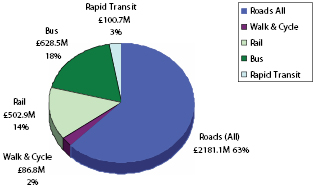

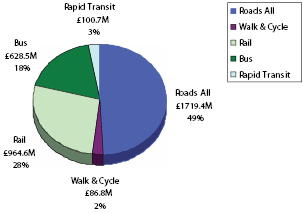

181. The Committee recommends that the balance of expenditures between roads and public transport in Budget 2011-2015, currently approximately 80:20, should be revisited over the course of this budget period with a view to supporting policy actions to reduce road transport related carbon emissions.

182. Examples from other jurisdictions and evidence received by the Committee suggest that land-use planning and transport planning must be integrated. There is an opportunity to do this and make sustainability a key element in the Regional Development Strategy (RDS) and the Regional Transportation Strategy (RTS), both of which are being consulted on at present. Links are also needed between the high level RDS and RTS and more localised Area Plans and Local Transport Plans if the commitment to sustainability is to be realised. The Committee recommends that this opportunity be taken as a matter of urgency and the RDS and RTS used to address the challenge of creating sustainable transport in Northern Ireland.

183. The Committee is of the view that sustainable transport would receive higher priority across government departments if robust carbon costing was included in business cases and sustainability issues were assigned higher weighting in government procurement.

184. Transport costs are a key element of any business, and have a direct impact on the cost of Northern Ireland's imports and the competitiveness of our exports. The Committee is of the view that now is the time to begin planning, in the long term, for more sustainable models of freight transport.

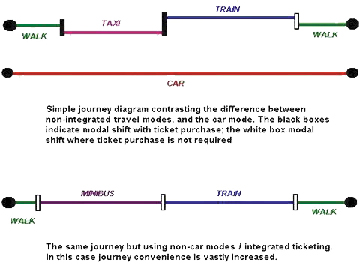

185. The Committee has expressed the view on many occasions that, modal shift will not be achieved unless and until public transport is prioritised in the allocation of road space, particularly in our city centres. This should be accompanied with actions to disincentivise private car use when viable alternative public transport options exist, for example, by reducing the number of car-parking spaces available or setting car-parking charges higher than park and ride tickets.

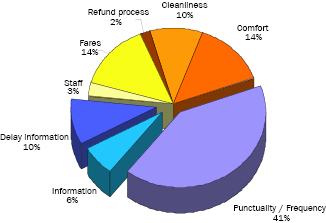

186. Consumer Council research has demonstrated that those using public transport want high quality, modern, reliable, clean and value for money public transport. Providing a service that meets these needs will increase the use of public transport.

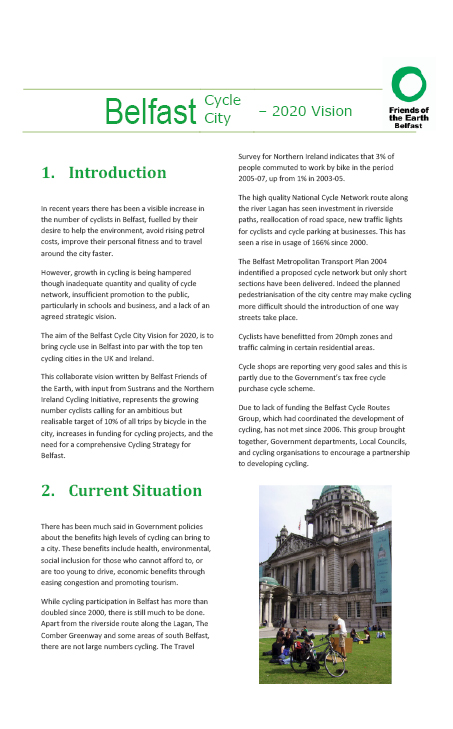

187. The Committee is aware of the existence of new and more established bike hire schemes in cities such as London and Paris, and is looking forward to seeing the outcome of the Belfast bike hire pilot scheme. In the interim, the Committee recommends that the Department takes the opportunity to review its existing walking and cycling strategies, with a view to promoting the development of walking and cycling plans by private sector employers, schools, colleges and universities.

188. Moving to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland requires attitudinal change from individuals, businesses and government. This section identifies the attitudes likely to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland.

189. The Committee recommends that the Department should develop a set of clear messages, aimed at the general public, on sustainable transport that identify the financial, social, health and environmental benefits of changing to more sustainable transport. This should include a menu of small changes that could be made in every-day life, many of which encompass current Departmental initiatives, for example, car-sharing to work, using public transport to work once a week, walking journeys of 1 mile or less and cycling journeys of less than 5 miles, substituting park and ride for some journeys etc. to promote understanding and change behaviours.

190. Attitudinal change is not just a matter for the public, and there is a need to make sustainability a key cross-cutting priority in the decision making processes of the Executive and the government departments. Government should lead by example, and the Committee recommends that the Executive acts to ensure departments consider the ways in which they do business. For example, do they provide free or subsidised car-parking to their staff, do they actively encourage remote or home working, do they use video-conferencing instead of travelling to meetings?

191. The Committee also recommends the application of a robust impact assessment tool to be used when evaluating bids for, as well as making allocations of, resources. The Committee is aware that this would have to be agreed with the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister and the Department of Finance and Personnel, and supported by championing from Minister and senior officials across the government departments.

192. The Committee is also of the view that opportunities exist to promote and achieve more sustainable transport planning across the wider public sector where, for example, sustainable transport planning for health visitors, community nurses, social workers, patients travelling to hospitals, school transport, and so forth, could be incentivised. In addition, both the private sector and the community and voluntary sector should be supported to develop sustainable travel and transport plans for their organisations.

193. Consumer Council research has shown that 25% of people state that they would never in any circumstances use public transport. The Committee recommends that the Department acts to understand why this group reports this opinion, and how this group could be encouraged to change its reported attitude to public transport use.

194. The Committee considered the evidence received, and has identified the following technologies, in the broadest sense, likely to underpin a move to more sustainable transport in Northern Ireland.

195. The Committee is of the view that, in the past, the solution to the problem of climate change was sometimes assumed to be the development of a cheap, convenient and clean technological alternative to fossil fuels. This 'magic bullet' technology would allow us to maintain our lifestyles unchanged. The debate has moved on and so have the technologies and, with the ongoing improvements in electric, hybrid and fuel-cell technologies the opportunity now exists to apply these technologies to public transport in Northern Ireland. The Committee recommends that the Department and Translink investigate the opportunities to apply the full range of "green" technologies to public transport in Northern Ireland.

196. The Committee noted the recently announced successful Office for Low Emissions Vehicles (OLEV) bid, and would encourage the Department for Regional Development and its partners to progress this project with all possible speed.

197. Changes in how we receive and exchange information as well as advances in ICT and the development of new media opens up the possibility of disseminating more accessible, integrated and timely information on public transport services. This could include, for example, information on next scheduled service, service delays, alternative routes, wi-fi on buses, text alerts re carbon saved by taking the journey a passenger is on etc. Technological developments will also facilitate the introduction of integrated on and off-board ticketing systems, including m-ticketing and other ICT based options, as well as incorporating flexible and accessible information and audio visual systems. The Department, together with Translink, should progress the application of these new media and technologies as a matter of immediacy.

198. The Committee recommends that, across government and the wider public sector, advances in the speed, security and costs of information and communications technologies (ICT) should be harnessed to develop alternatives to our current patterns of travel and commuting-dependent ways of working, through increased home-working, remote or teleworking.

199. Integration in public transport does not simply mean ensuring that Translink's services are joined-up. The Committee recommends that the Department and Translink works with other bodies to integrate initiatives such as bike schemes and bike parks and private car-clubs with scheduled public transport provision.

200. Almost half of Northern Ireland's road transport GHG emissions are accounted for by freight transport. The cost and efficiency of doing business in Northern Ireland is highly dependent on transport costs, and the majority of freight in Northern Ireland is transported by road. The Committee noted material provided on new models and technologies in logistics and supply chain management which can make a valuable contribution to more sustainable freight transport. Members are also aware of the work being undertaken by the Freight Forum. The Committee is of the view that freight related emissions must be addressed, however great care must be taken in how this is achieved, especially given the difficulties faced by all businesses in the current economic climate. The Committee recommends that new technologies and advances in logistics and supply chain management be further explored by the Department, the freight industry and businesses with a view to developing a long-term emissions reduction plan for the freight sector.

[1] http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/transport/ecmt-annual-report-2004_9789282103463-en

[2] http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/transport/ecmt-annual-report-2004_9789282103463-en

[3] http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/transport/ecmt-annual-report-2004_9789282103463-en

[4] http://www.sustainable-development.gov.uk/publications/pdf/SD_Framework.pdf

[5] http://www.dft.gov.uk/about/strategy/transportstrategy/eddingtonstudy/

[6] http://www.ippr.org.uk/publicationsandreports/publication.asp?id=530

[7] Research Papers provided by the Assembly's Research and Library Service, see Appendix 6 of this report.

[8]http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_change/sternreview_index.cfm

[9] http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/king_review/king_review_index.cfm

[11] http://www.dft.gov.uk/about/strategy/transportstrategy/eddingtonstudy/

[12] http://www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/inclusion/sitransportaspects.pdf

[13] http://www.sustrans.org.uk/webfiles/Info_sheets/FF46_info_sheet.pdf

[14] http://www.healthandtransportgroup.co.uk/articles/makingcase_health_transport.pdf

[15] http://www.ippr.org.uk/publicationsandreports/publication.asp?id=541

[16] Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Action Plan (2011), p.16

[17] http://doeni.gov.uk/northern_ireland_action_plan-on-greenhouse-gas_emissions_reductions.pdf

[18] Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Action Plan (2011), p.20-21 and 86

[19] Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Action Plan (2011), p.27

Present: Fred Cobain, MLA (Chairperson)

Cathal Boylan, MLA

Allan Bresland, MLA

Willie Clarke, MLA

John McCallister, MLA

Raymond McCartney, MLA

George Robinson, MLA

Alastair Ross, MLA

Jim Wells, MLA

Brian Wilson, MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Kelly (Assembly Clerk)

Conor Coughlin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Pauline Devlin (Clerical Supervisor)

Annette Page (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: John Dallat, MLA

10.33 am Members decided to commence the meeting in open session.

Members noted receipt of the list of participants for the Assembly Research and Library Services' stakeholder event regarding sustainable transport scheduled for 6 February 2009. Members also noted that the Committee is planning to begin work on the inquiry following the Easter recess period.

[EXTRACT]

Present: Fred Cobain, MLA (Chairperson)

Allan Bresland, MLA

John Dallat, MLA

John McCallister, MLA

George Robinson, MLA

Jim Wells, MLA

Brian Wilson, MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Kelly (Assembly Clerk)

Conor Coughlin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Andrew Larmour (Clerical Supervisor)

Annette Page (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Cathal Boylan, MLA

Willie Clarke, MLA

Raymond McCartney, MLA

Alastair Ross, MLA

10.37am Members decided to commence the meeting in open session.

Members noted receipt of correspondence, dated 12 March 2009, from William Wright, Group Director of Wright Group Limited requesting that the Committee presses the Assembly and the Executive for their engagement and constructive support as it and its workforce try to weather the economic storm. The Chairperson informed Members that both he and the deputy Chairperson have arranged to meet with the Minister for Regional Development on Thursday 19 March 2009 on other matters, and Members agreed that the Chairperson and deputy Chairperson should raise this correspondence at the meeting with the Minister for Regional Development. Members also decided to invite Wright Bus to provide evidence to the Committee on its work on new technologies for public transport vehicles as part of the Committee inquiry into Sustainable Transport.

[EXTRACT]

Present: Fred Cobain, MLA (Chairperson)

Cathal Boylan, MLA

Allan Bresland, MLA

Willie Clarke, MLA

John McCallister, MLA

Raymond McCartney, MLA

George Robinson, MLA

Alastair Ross, MLA

Jim Wells, MLA

Brian Wilson, MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Kelly (Assembly Clerk)

Conor Coughlin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Andrew Larmour (Clerical Supervisor)

Annette Page (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: John Dallat, MLA

10.40am Members decided to commence the meeting in open session.

Members noted receipt of an email, dated 16 April 2009, from Tom McCelland, Chairperson of the Northern Ireland Cycling Forum regarding the Committee's planned inquiry into sustainable transport. Members decided to respond to Mr McClelland, informing him of the proposed start date and format of the planned inquiry.

[EXTRACT]

Present: Fred Cobain, MLA (Chairperson)

Cathal Boylan, MLA

Allan Bresland, MLA

Willie Clarke, MLA

John McCallister, MLA

Raymond McCartney, MLA

George Robinson, MLA

Alastair Ross, MLA

Jim Wells, MLA

Brian Wilson, MLA.

In Attendance: Roisin Kelly (Assembly Clerk)

Conor Coughlin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Andrew Larmour (Clerical Supervisor)

Annette Page (Clerical Officer).

Apologies: John Dallat, MLA

10.35am Members decided to commence the meeting in open session.

Members noted receipt of a letter, dated 6 March 2009, from the office of Sir Reg Empey, forwarding a letter from Bob Pue, Chief Executive of the Great Northern Ireland Railway (Ireland). Following consideration of the correspondence, Members decided to write to Mr Pue outlining the Committee's work on this topic, and informing him of the Committee's planned inquiry into sustainable transport.

[EXTRACT]

Present: Fred Cobain, MLA (Chairperson)

Cathal Boylan, MLA

Willie Clarke, MLA

John Dallat, MLA

John McCallister, MLA

Raymond McCartney, MLA

George Robinson, MLA

Alastair Ross, MLA

Brian Wilson, MLA.

In Attendance: Roisin Kelly (Assembly Clerk)

Conor Coughlin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Stephanie Galbraith (Researcher)

Andrew Larmour (Clerical Supervisor)

Annette Page (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Allan Bresland, MLA

Jim Wells, MLA.

10.35am Members decided to commence the meeting in open session.