Session 2007/2008

Fifth Report

Public Accounts committee

Report on

Tackling Public Sector Fraud

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE RELATING

TO THE REPORT AND THE MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

Ordered by Public Accounts committee to be printed 13 December 2007

Report: 13/07/08R (Public Accounts committee)

Public Accounts Committee

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts and reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 51 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Willie Clarke* Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Jonathan Craig Mr Patsy McGlone

Mr John Dallat Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Simon Hamilton Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr David Hilditch

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke on 1st October 2007

Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report v

Report

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

Introduction

Learning Lessons from the Agency’s Fraud

Wider Counter Fraud Initiatives

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2:

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3:

Fraud Prevention: Update from Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts,

Departments of Finance and Personnel

Chairperson’s letter of 22 October 2007 to Mr Paul Sweeney, Accounting Officer,

Department of Culture. Arts and Leisure

Correspondence of 2 November 2007 from Mr Paul Sweeney, Accounting Officer,

Department of Culture. Arts and Leisure

Chairperson’s letter of 22 October 2007 to Mr Bruce Robinson, Accounting Officer,

Department of Finance and Personnel

Correspondence of 30 October 2007 from Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel

Appendix 4:

List of Witnesses

List of Abbreviations

used in the Report

The Agency Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland

The Department Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

LEDU Local Enterprise Development Unit

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

NDPBs Non Departmental Public Bodies

TOA Treasury Officer of Accounts

FE Further Education

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland (the Agency) is an executive agency within the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (the Department) with responsibility for the supply of mapping and geographical information services for Northern Ireland.

2. In August 2003, an internal fraud was uncovered within the Accounts Branch of the Agency and a subsequent investigation found that the fraudster, a supervisor, had defrauded the Agency of £70,690. The fraudster was formally charged by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) with stealing cash and falsifying records. On 20 January 2006, he pleaded guilty to the charges at Belfast Crown Court and on 7 April 2006 he was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment, suspended for two years.

3. Because fraud is an ever present threat, the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) has a key role to play in co-ordinating the drive across the public sector to combat fraud. This includes the dissemination of Public Accounts Committee recommendations; guidance on counter fraud best practice; sharing of data and information through a Fraud Forum; an annual report on the types, causes and means of discovery of fraud; and the regular monitoring and review of legislation.

Learning Lessons from the Agency’s Fraud

4. This fraud was not particularly sophisticated in nature and was due in large part to serious shortcomings in the control environment. Although the Agency detailed a range of controls it had subsequently put in place, their omission at the time of the fraud reflects a significant failing on its part.

5. Supervisory negligence also played a major part in allowing this fraud to occur and to remain undetected for so long. Following an independent investigation, one member of staff received a written warning while another escaped censure. The Committee questions whether the disciplinary action taken against these supervisory staff was sufficiently robust. The Committee is satisfied that if a similar degree of negligence occurred in the private sector, it would be sanctioned more severely.

6. The fraud occurred over a five year period from 1998 to 2003, despite a number of clear and consistent warning signals which should have led to it being detected much earlier. It was only discovered while the fraudster was on extended sick leave and the basic failure to ensure segregation of duties means that it is quite possible that, were it not for his sickness absence, these fraudulent activities could have continued for a further considerable period. It is clear to the Committee that there was a lack of a counter fraud culture in the Agency at this time and that many of the warning signals were ignored.

7. The Department told the Committee that it has learnt lessons from this fraud. However, it is notable that this was not the first fraud in the Agency. Furthermore, there are also elements of this case which resonate with the evidence given to the previous Public Accounts Committee in relation to a fraud in the former Local Enterprise Development Unit (LEDU). It is disturbing that the lessons from both the previous fraud in LEDU and in the Agency itself were not learnt and that the same types of control and supervisory failures recurred.

8. On discovery of the fraud, the Agency immediately established a Case Management Group to oversee the investigation. This appears to have worked effectively and to represent a good model for the investigation process. In addition, the Agency effected full restitution of the money stolen. This sends out an important message that the full rigours of the law will be brought to bear against those who commit fraudulent acts against the public purse.

9. An interesting aspect of this case was the Department’s decision, on unequivocal legal advice, not to pursue the option of seeking forfeiture of the fraudster’s pension rights. The Committee believes that the forfeiture of pension rights, whether in whole or in part, must be a remedy that can be applied against public servants who defraud the public purse and where restitution cannot otherwise be obtained.

Wider Counter Fraud Initiatives

10. The Serious Crime Bill will provide new data matching and data sharing powers. This will enable the public sector to share data both internally and with the private sector for the prevention and detection of fraud. It will also allow the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) to replicate data matching exercises similar to those conducted by the Audit Commission in England and Wales to identify cases which could signify fraud or error. The first fruits of this exercise should appear within 12 to 18 months and savings of £4 million may be attainable in Northern Ireland.

11. The Fraud Forum is a best practice counter fraud advisory group established by DFP. While the Committee welcomes the work of the Fraud Forum, it is concerned that lessons may not be disseminated effectively to bodies at arm’s length from central government.

12. The Fraud Forum has produced a “Memorandum of Understanding between the Public Sector and the PSNI”. However, fraud can occur anywhere and, if there is genuinely to be zero tolerance of fraud, the Committee believes it is essential that the public sector has the capacity, and a sufficient number of trained investigators, to deliver its responsibilities under the memorandum.

13. DFP produces an Annual Fraud Report, covering suspected and proven frauds involving public funds. The Committee sees the Fraud Report as a potentially useful source of information. However the report is limited in scope. It does not quantify the total value of frauds; does not include the substantial risk areas of social security, agriculture and prescription frauds; and does not analyse, by type of body, where fraud occurs.

14. DFP recently commissioned a survey of 120 public sector bodies to assess their implementation of counter fraud measures. While recognising that the overall results are relatively positive, the Committee also notes some areas of weakness. One specific area of concern relates to the absence of whistle-blowing policies in 25% of the bodies. This is a valuable element of a good counter fraud strategy that all public sector bodies should have in place.

Summary of Recommendations

Learning Lessons from the Agency’s Fraud

1. Departments and their agencies cannot afford to simply assume that the controls they have in place are sufficient and are working effectively. The Committee recommends that in high risk areas, such as cash handling, management must assure themselves that controls are appropriate and are being applied rigorously. Management should put in place arrangements commensurate with the level of risk involved to test and record the level of compliance. All managers and supervisors should be fully aware of their responsibilities (see paragraph 11).

2. The Committee considers that the limited disciplinary action in this case does not send the right signal about the seriousness of ineffective supervision. In future cases departments must give full weight to the Committee’s concern on this matter. DFP should review the range of disciplinary sanctions available for supervisory negligence in cases of internal fraud and ensure they are applied effectively (see paragraph 15).

3. The Committee recommends that senior line management should ensure that payment of bonuses to supervisory staff in an area of work where a fraud has been discovered must be prepared to offer robust and compelling explanations to justify such payments (see paragraph 16).

4. It is important that a strong counter fraud culture is embedded within all public sector organisations. The Committee recommends that DFP, in consultation with departments and agencies, devises and implements a strategy for firmly embedding a counter fraud culture in all parts of the public sector (see paragraph 20).

5. It is disturbing that lessons from previous frauds in LEDU and in the Agency itself were not learnt and that the same types of control failures recurred. It is important that public bodies are fully and regularly apprised of the key facts pertaining to all internal frauds. The Department has used this case study with its Arm’s Length Bodies. However, the Committee believes that the lessons from this case need to be learned more widely and recommends that DFP encourages other departments to use it in their efforts to raise awareness of internal fraud (see paragraph 24).

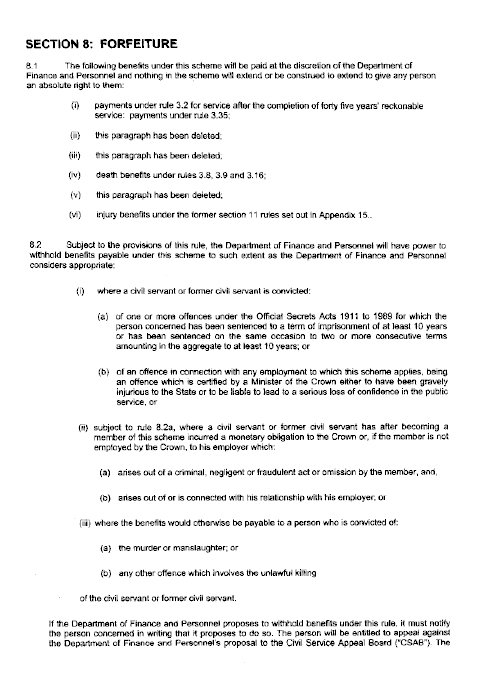

6. A fraud on this scale is precisely the type of activity which is liable to lead to a serious loss of confidence in the public service and should therefore qualify for forfeiture of pension rights. The Committee recommends that DFP reviews the legislation on this issue to ensure that forfeiture can be applied if full restitution has not been made. DFP should issue guidance to departments on the procedures for initiating such action in cases of proven internal fraud (see paragraph 30).

Wider Counter Fraud Initiatives

7. The Committee wishes to be consulted on the proposed protocols for data matching (see paragraph 35).

8. The Committee recommends that the Fraud Forum satisfies itself that the wider public sector is informed of its work and that each department has established mechanisms to ensure that the advice and guidance emanating from the Forum is systematically disseminated to all its subsidiary bodies (see paragraph 38).

9. It is important that efforts to detect, investigate and prosecute fraud are not undermined by a lack of capacity and expertise in the wider public sector. The Committee recommends that DFP undertakes a stocktaking exercise across the wider public sector to assess the availability of trained investigation staff on front line investigation work, and, if necessary, devises a strategy to fill any skills gaps identified by this exercise through mechanisms such as training programmes or short-term redeployment of existing resources (see paragraph 42).

10. In the Committee’s view, there is scope to improve the Fraud Report in order to offer better quality information. The Committee recommends that it should report, at least in summary, on all fraud in the public sector, quantify the value of that fraud and analyse the types of public sector body in which fraud occurs. The Fraud Report should be presented annually to this Committee (see paragraph 48).

11. The Committee would like to see much more emphasis given to whistle-blowing as an important means of identifying potential fraudulent activity. There is no excuse for 25% of departments and agencies not having whistle-blowing policies in place and we expect DFP to ensure this deficit is addressed and that full compliance is achieved. The Committee also expects DFP to ensure that departments are proactive in training and encouraging staff to blow the whistle and for DFP to include an analysis of activity levels of whistle-blowing across departments, as part of its annual Fraud Report (see paragraph 54).

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee met on 18 October 2007 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report: “Internal Fraud in Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland” (HC187, Session 2006-07). The Committee also considered a written submission from the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) entitled “Fraud Prevention: Update for PAC (September 2007)”. The witnesses were:

- Mr Paul Sweeney, Accounting Officer, Department of Culture, Arts & Leisure.

- Mr Iain Greenway, Chief Executive, Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland, Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

- Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel.

- Mr Ciaran Doran, Deputy Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel.

- Ms Alison Caldwell, Fraud and Internal Policy, Department of Finance and Personnel.

- Mr John Dowdall CB, Comptroller and Auditor General.

The Committee also took written evidence from Mr Sweeney and Mr Thomson.

2. Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland (the Agency) is an Executive Agency within the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (the Department). In August 2003, an internal fraud was uncovered within the Agency’s Accounts Branch. The fraud had been perpetrated over a five year period between 1998 and 2003 during which the fraudster stole £70,690. The fraudster was subsequently charged, pleaded guilty to the offences and was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment, suspended for two years. The Agency achieved full restitution of the monies stolen.

3. In taking evidence on the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report, the Committee focussed on a number of issues. These were:

- the weaknesses in controls and supervision which contributed to the fraud;

- the failure to identify the fraud sooner and learn lessons from previous frauds; and

- the investigation of the fraud and its successful prosecution.

4. Turning to wider fraud initiatives, the Committee scrutinised several aspects of DFP’s submission (see Appendix 3) including:

- the proposed introduction of data matching legislation;

- the role of DFP in providing counter fraud advice and guidance; and

- the extent to which counter fraud measures are in place across the whole of the public sector.

Learning Lessons

from the Agency’s Fraud

General Findings

5. This case of internal fraud focuses on a number of serious shortcomings in the Agency’s ability to deter fraud through strong governance arrangements. To have one fraud may be regarded as misfortune but two looks like downright carelessness. Failures of this sort are traumatic for everyone; cause serious reputational damage to the Department and Agency; and are stressful and demoralising for the fraudster’s colleagues and tragic for him and his family.

6. There are important lessons to be drawn from this case and we look to DFP to ensure that these lessons are disseminated widely across the public sector and bodies take heed of them. The Committee would like the C&AG to bring to our attention any cases of serious fraud so that the Committee can examine the lessons to be learned and require departments to address them.

Weaknesses in the Control Environment

7. Although there was a degree of cunning involved in perpetrating this fraud, it was not particularly sophisticated in nature and was due in large part to serious shortcomings in the control environment. The fraudster was able to open the post on his own, remove cheques and exchange the cheques with cash from the Agency’s Map Shop. He then raised false credit notes to cover his tracks.

8. A number of factors enabled the fraud to be perpetrated. There was inadequate segregation of duties and cash and cheques were not securely stored. There were failures of supervision, illustrated by the Finance Manager (the fraudster’s supervisor) withdrawing from the day-to-day operations of Accounts Branch at a time when the Agency was experiencing a rapid increase in turnover. There was no financial procedures manual which meant that staff were not in a position to recognise or challenge whether appropriate controls were being applied.

9. The control framework in place was wholly inadequate and the Committee very much welcomes the Accounting Officer’s frankness in recognising these weaknesses. The Department assured the Committee that it had immediately implemented a number of actions to improve the control framework and that the chances of fraud were now much less. While the Agency detailed a range of controls it had subsequently put in place, their omission at the time of the fraud reflects a significant failing on its part.

10. DFP added that there is a requirement for Accounting Officers to sign a Statement of Internal Control providing assurance that departments carry out sufficiently robust and frequent testing of their controls. While we accept that this measure provides useful assurance on the control environment, we are not persuaded that it will necessarily ensure the regular testing of controls at business or branch unit level, which is necessary.

Recommendation 1

11. Departments and their agencies cannot afford to simply assume that the controls they have in place are sufficient and are working effectively. The Committee recommends that in high risk areas, such as cash handling, management must assure themselves that controls are appropriate and are being applied rigorously. Management should put in place arrangements commensurate with the level of risk involved to test and record the level of compliance. All managers and supervisors should be fully aware of their responsibilities.

Supervisory Negligence

12. Supervisory negligence also played a major part in allowing this fraud to occur and to remain undetected for so long. The Department told the Committee that the fraudster had worked for the organisation for 25 years and that excessive trust was placed in this individual, who had an unblemished record. The Department accepted that this should never have been allowed to happen.

13. Following its discovery, the Agency commissioned an independent investigation to examine management oversight during the period of the fraud. This concluded that the Finance Manager had failed to properly supervise the fraudster and had fallen short, to a significant extent, of the role expected of him. The Finance Manager received a written reprimand, to remain on his record for three years. A professional accountant within Accounts Branch had identified concerns as early as October 2002, based on queries from customers, but had failed to ensure there was follow-up action before leaving the Agency shortly thereafter. The investigation recommended that this officer should not be subject to disciplinary action.

14. On the basis of the evidence, the Committee questions whether the disciplinary action taken against these supervisory staff was sufficiently robust. A written reprimand is, in the Committee’s view, one of the mildest sanctions available in the Civil Service, while the lack of disciplinary action against the accountant sends a weak message about tolerating supervisory failures. The Committee is satisfied that, if a similar degree of negligence occurred in the private sector, it would be sanctioned more severely.

Recommendation 2

15. The Committee considers that the limited disciplinary action in this case does not send the right signal about the seriousness of ineffective supervision. In future cases departments must give full weight to the Committee’s concern on this matter. DFP should review the range of disciplinary sanctions available for supervisory negligence in cases of internal fraud and ensure they are applied effectively.

Recommendation 3

16. The Committee recommends that senior line management should ensure that payment of bonuses to supervisory staff in an area of work where a fraud has been discovered must be prepared to offer robust and compelling explanations to justify such payments.

Failures to Detect the Warning Signs of Fraud

17. This fraud occurred over a five year period from 1998 to 2003, despite a number of clear and consistent warning signals which should have led to it being detected much earlier. In particular, queries and complaints were being received from customers who had paid their bills by cheque. In the Department’s view, the tipping point was around October 2002, when the accountant raised specific concerns about customer queries, but failed to follow these up.

18. However, the Department also contended that it was only a matter of time before the fraud was discovered. The Agency was in the process of undertaking an exercise to address its bad debt situation and the Department claimed there was an inevitability that, through this process, the fraud would have been detected. The Committee is not convinced that this is in fact the case. The fraud was only discovered while the fraudster was on extended sick leave and the basic failure to ensure segregation of duties means that it is quite possible that, were it not for his sickness absence, these fraudulent activities could have continued for a further considerable period.

19. It is clear to the Committee that there was a lack of a counter fraud culture in the Agency at this time and that many of the warning signals were ignored. The Department has acknowledged that the presumption was that there was a failure in the systems and that the culture should have been more cognisant of the possibility of fraud. The fact that no fraud awareness training had been provided in the Agency at the time of the fraud and that it failed to introduce a whistle-blowing policy until 2003 are symptomatic of the lack of a counter fraud culture.

Recommendation 4

20. It is important that a strong counter fraud culture is embedded within all public sector organisations. The Committee recommends that DFP, in consultation with departments and agencies, devises and implements a strategy for firmly embedding a counter fraud culture in all parts of the public sector.

Learning the Lessons from Previous Frauds

21. The Department told the Committee that it has learnt lessons from this fraud. It has used it in a case study with its other arm’s length bodies; the fraud has also featured as a topic for discussion at the DFP Fraud Forum; and the Department has commissioned a series of Governance and Accountability audits in all its arm’s length bodies.

22. The Committee commends these actions. However, it is notable that this was not the first fraud in the Agency. A previous, smaller, fraud had occurred from 1988 to 1991 in the Agency’s Map Shop. The Committee is astonished that lessons were not more fully learnt from the first fraud, particularly as cursory supervision and control environment weaknesses had also been evident in this case. The Department acknowledged that there was an insufficient connection made at that time between the front office activities of the Agency’s Map Shop (where the first fraud occurred) and the back office activities of its Accounts Branch.

23. There are also elements of this case which resonate with the evidence given to the previous Public Accounts Committee in relation to a fraud in the former Local Enterprise Development Unit (LEDU). In this instance also, inadequate segregation of duties and poor supervisory controls were contributory factors.

Recommendation 5

24. It is disturbing that lessons from previous frauds in LEDU and in the Agency itself were not learnt and that the same types of control failures recurred. It is important that public bodies are fully and regularly apprised of the key facts pertaining to all internal frauds. The Department has used this case study with its Arm’s Length Bodies. However, the Committee believes that the lessons from this case need to be learned more widely and recommends that DFP encourages other departments to use it in their efforts to raise awareness of internal fraud.

Effective Investigation, Prosecution and Restitution

25. On discovery of the fraud, the Agency immediately established a Case Management Group to oversee the investigation. This appears to have worked effectively and to represent a good model for the investigation process. The subsequent success of the prosecution highlights the importance of establishing a fraud investigation team immediately, implementing a Fraud Response Plan, taking action to protect the evidence and establishing working arrangements with the PSNI.

26. In this case, the court imposed a penalty of £30,000 on the fraudster and the Department initiated civil action to recover the balance of £40,690. In July 2007, the Department received this balance and therefore successfully achieved restitution of the total amount defrauded. This sends out an important message that the full rigours of the law will be brought to bear against those who commit fraudulent acts against the public purse. The Committee welcomes the fact that full restitution was made in this case and hopes that it acts as a salutary lesson to any public servant tempted to consider undertaking fraud.

27. Equally, the Committee recognises that any fraud of this nature imposes additional burdens on the public purse over and above the amount defrauded. It is evident that there were a range of detection, investigation, and prosecution costs incurred by the Agency and the wider criminal justice system for which the public purse was not recompensed.

28. An interesting aspect of this case was the Department’s decision, on unequivocal legal advice, not to pursue the option of seeking forfeiture of the fraudster’s pension rights. The Department indicated that there are two situations in which forfeiture can be considered, one of which is where a Minister certifies that actions would be liable to lead to a serious loss of confidence in the public service. We asked to see the legal advice but were surprised that no written legal advice was provided by the Departmental Solicitor to the Agency. In the absence of written advice from the Departmental Solicitor it is not clear why forfeiture of the fraudster’s pension could not be pursued.

29. In this case, because full restitution was achieved by other means, the issue of forfeiture of pension rights was not tested. This Committee believes that the forfeiture of pension rights, whether in whole or in part, would be a strong deterrent against internal fraud and must be a remedy that can be applied against public servants who defraud the public purse and where restitution cannot otherwise be obtained.

Recommendation 6

30. A fraud on this scale is precisely the type of activity which is liable to lead to a serious loss of confidence in the public service and should therefore qualify for forfeiture of pension rights. The Committee recommends that DFP reviews the legislation on this issue to ensure that forfeiture can be applied if full restitution has not been made. DFP should issue guidance to departments on the procedures for initiating such action in cases of proven internal fraud.

Wider Counter Fraud Initiatives

Legislative Developments

31. DFP updated the Committee on the implications for Northern Ireland of the Fraud Review. This was a UK-wide exercise commissioned by the Attorney General and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury on ways to reduce fraud and the damage that it causes to the economy and society.

32. The Committee notes that the most significant impact from the UK-wide Fraud Review on Northern Ireland will be the new data sharing and data matching powers provided under the Serious Crime Bill[1], a UK piece of legislation. DFP indicated that protocols and codes of practice need to be put in place for the sharing of information and noted the need to strike a balance between protecting individuals and sharing data.

33. Data sharing will enable the public sector to share data both internally and with the private sector for the purpose of preventing and detecting fraud. Data matching is mandatory and will enable the C&AG to replicate data matching exercises similar to those conducted by the Audit Commission in England and Wales to identify cases which could signify fraud or error. The most recent exercise generated financial savings of £111 million in England and Wales and, by preventing and detecting fraud and error, it can therefore generate significant savings. A pro-rata estimate for Northern Ireland would suggest savings of £4 million are attainable.

34. The C&AG suggested that the first fruits of this exercise would appear within 12 to 18 months. He highlighted that Northern Ireland’s participation in the legislation was due to DFP’s initiative. The Committee commends DFP for its work in ensuring Northern Ireland’s participation in the National Fraud Initiative, and welcomes the fact that protocols will be established to safeguard individuals’ rights.

Recommendation 7

35. The Committee wishes to be consulted on the proposed protocols for data matching.

The Role of DFP’s Fraud Forum

36. DFP established the Fraud Forum in March 2005 as a best practice advisory group. The Fraud Forum provides an opportunity to offer advice and guidance to departments and so fits well with DFP’s own emphasis on prevention. As an example of its work, DFP noted that it had held a major counter fraud conference for the wider public sector in October 2006.

37. The Committee questioned DFP on the merits of extending membership to include the wider public sector and the voluntary sector. In response, DFP indicated that it is content with the current structure of the Fraud Forum and indicated that it is for departments and Accounting Officers to take responsibility for their arm’s length bodies. As currently constituted, DFP feels the Fraud Forum is useful for discussing and sharing best practice and cascading lessons. It accepted, however, that it should review the membership on a continued basis. While the Committee welcomes the work of the Fraud Forum as a means of offering best practice advice, it is concerned that lessons may not be disseminated effectively to bodies at arm’s length from central government.

Recommendation 8

38. The Committee recommends that the Fraud Forum satisfies itself that the wider public sector is informed of its work and that each department has established mechanisms to ensure that the advice and guidance emanating from the Forum is systematically disseminated to all its subsidiary bodies.

39. The Fraud Forum has produced a series of best practice guidance notes including, most notably, a “Memorandum of Understanding between the Public Sector and the PSNI”. This established a basic framework for the working relationship in the investigation and prosecution of suspected fraud cases and is supported by more detailed procedural guidelines.

40. The Committee asked DFP about the availability of suitably qualified staff to undertake fraud investigations across the wider Public Sector. DFP explained that most investigations are carried out by trained investigators or internal audit staff and emphasised that in high risk areas, such as social security, prescription fraud and agriculture, there are trained investigators and teams in place. The memorandum is aimed at staff who are not trained investigators and is designed to ensure bodies act in a manner which will not prejudice a prosecution.

41. However, fraud can occur anywhere and, if there is genuinely to be zero tolerance of fraud, the Committee believes it is essential that the public sector has the capacity, and a sufficient number of trained investigators, to address this risk and to deliver its responsibilities under the memorandum. Pressure on fraud investigation resources is likely to increase when public sector bodies are expected to investigate those cases detected by the new data matching powers.

Recommendation 9

42. It is important that efforts to detect, investigate and prosecute fraud are not undermined by a lack of capacity and expertise in the wider public sector. The Committee recommends that DFP undertakes a stocktaking exercise across the wider public sector to assess the availability of trained investigation staff on front line investigation work, and, if necessary, devises a strategy to fill any skills gaps identified by this exercise through mechanisms such as training programmes or short-term redeployment of existing resources.

DFP’s Fraud Report

43. Departments are required to report suspected and proven frauds to DFP. This facilitates the production of an Annual Fraud Report covering departments, agencies, NDPBs and public funds disbursed by voluntary bodies and other agents. In 2006-07, departments reported 116 cases of actual and suspected fraud with an estimated value of £1.53 million.

44. Grant fraud accounted for 26% of the cases reported and affected eight departments. These types of fraud generally reflect a failure to meet a condition of the grant. DFP also provided illustrations of other categories recorded in the Fraud Report. These ranged from small scale thefts of individual items such as laptops and cameras, through to frauds relating to income (as with the Agency case) and payment processes. The latter included abuse of credit cards, wrongful ordering and diverted delivery of goods.

45. The Committee notes that the three biggest areas of risk (Social Security, Agriculture and Prescription frauds) are not included in the Fraud Report but are all reported on separately by the respective departments. Latest figures indicate that annual fraud in these three areas amounted to almost £28 million.

46. The Committee asked DFP whether there was a greater propensity for fraud to occur in certain types of bodies. Subsequent information provided by DFP (see Appendix 3) suggests that the risks of fraud may be greater in bodies which are at arm’s length from departments.

47. The Committee sees the Fraud Report as a potentially useful source of information. Currently, however, the report does not quantify the value of frauds; does not include the substantial risk areas of social security, agriculture and prescription fraud; and does not analyse, by type of body, where fraud occurs.

Recommendation 10

48. In the Committee’s view, there is scope to improve the Fraud Report in order to offer better quality information. The Committee recommends that it should report, at least in summary, on all fraud in the public sector, quantify the value of that fraud and analyse the types of public sector body in which fraud occurs. The Fraud Report should be presented annually to this Committee.

Counter Fraud Measures Across the Public Sector

49. The Agency fraud case illustrated where management had failed to adequately test the robustness of its control systems. In response, DFP noted that there is now a requirement for Accounting Officers to sign a Statement of Internal Control and that this process provides greater assurances on the robustness of systems in public sector. DFP also noted that it had gained assurances through a survey of counter fraud measures which it had recently commissioned. This covered 120 public sector organisations and, DFP indicated that the results suggested departments generally had counter fraud measures in place.

50. While recognising that the overall results are relatively positive, the Committee notes some areas of weakness. For example some 25% of respondents had not undertaken an overall fraud risk assessment. DFP acknowledged that this was disappointing, but indicated that it was clear to them from other responses to the questionnaire that bodies were actually tackling the risk of fraud through other risk management processes, such as Fraud Response Plans and Fraud Policy Statements.

51. The Committee welcomes DFP’s survey of counter fraud measures across the wider public sector, regarding it as a good benchmark and one that should be built on. However there are risks with self-assessment surveys, such as complacency and that respondents tell you what they think you want to hear. It is therefore important that DFP does not place too much emphasis on this as a source of evidence but reinforces to departments the Government Accounting requirements to carry out a systematic assessment of fraud risk, as part of a continuous cycle, at both organisational and operational levels.

52. One specific area of concern to the Committee relates to the issue of whistle-blowing policies. DFP confirmed that a requirement already exists to report anything irregular under the Code of Ethics. It indicated that, as only around 3% of serious frauds were identified through whistle-blowing, it was not a priority compared with other mechanisms such as internal controls that play a much greater part in fraud prevention. Nevertheless, it is currently developing a model template which would provide a more open and formal procedure for whistle-blowing.

53. The Committee welcomes the development of the whistle-blowing template and notes that one of the lessons from the Agency case study is the potential for whistle-blowing to facilitate earlier detection of wrongdoing. This is a valuable element of a good counter fraud strategy that all public sector bodies should have in place.

Recommendation 11

54. The Committee would like to see much more emphasis given to whistle-blowing as an important means of identifying potential fraudulent activity. There is no excuse for 25% of departments and agencies not having whistle-blowing policies in place and we expect DFP to ensure this deficit is addressed and that full compliance is achieved. The Committee also expects DFP to ensure that departments are proactive in training and encouraging staff to blow the whistle and for DFP to include an analysis of activity levels of whistle-blowing across departments, as part of its annual Fraud Report.

Minutes of Proceedings

of The Committee

Relating to the Report

Thursday, 18 October 2007

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

In Attendance: Mrs Cathie White (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Gillian Lewis (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Nicola Shephard (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr John Dallat

Mr Patsy McGlone

The meeting opened at 2.00pm in public session.

2.04pm Ms Purvis joined the meeting.

3. Evidence on the NIAO Report ‘Internal Fraud in Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland’

The Committee took oral evidence on the NIAO report ‘Internal Fraud in Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland’ from Mr Paul Sweeney, Accounting Officer, Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure and Mr Iain Greenway, Chief Executive, Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland. The witnesses answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

The Committee requested that the witnesses should provide additional information on issues raised by members during the evidence session to the Clerk.

3.13pm The evidence session finished and the witnesses left the meeting.

4. Evidence on Fraud Prevention

The Committee took oral evidence on fraud prevention from Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP), Mr Ciaran Doran, Deputy Treasury Officer of Accounts, DFP, and Ms Alison Caldwell, Head of Fraud and Internal Policy, DFP. The witnesses answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

The Committee requested that the witnesses should provide additional information on issues raised by members during the evidence session to the Clerk.

4.11pm The evidence session finished and the witnesses left the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday, 13 December 2007

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Patsy McGlone

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

In Attendance: Mrs Cathie White (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Gillian Lewis (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Nicola Shephard (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Trevor Lunn

The meeting opened at 2.00pm in public session.

2.05pm Ms Purvis joined the meeting.

2.23pm The meeting went into closed session.

10. Consideration of Draft Committee Report on Tackling Public Sector Fraud.

Members considered the draft report paragraph by paragraph. The witnesses attending were Mr John Dowdall CB, C&AG, Mr Eddie Bradley, Director of Value for Money, Mr Patrick O’Neill, Audit Manager, and Mr Joe Campbell, Audit Manager.

The Committee considered the main body of the report.

Paragraphs 1 – 10 read and agreed.

Paragraph 11 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 12 – 13 read and agreed.

Paragraph 14 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 15 read and agreed.

Paragraph 16 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 17 – 18 read and agreed.

Paragraph 19 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 20 – 21 read and agreed.

Paragraph 22 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 23 – 27 read and agreed.

Paragraph 28 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 29 read and agreed.

Paragraph 30 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 31 – 41 read and agreed.

Paragraph 42 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 43 – 50 read and agreed.

Paragraph 51 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 52 – 54 read and agreed.

The Committee considered the Executive Summary of the report.

Paragraph 1 read and agreed.

Paragraph 2 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 3 – 5 read and agreed.

Paragraph 6 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 7 – 14 read and agreed.

Agreed: Members ordered the report to be printed.

Agreed: Members agreed that the Chairperson’s letters requesting additional information to Mr Paul Sweeney and Mr Bruce Robinson, and the responses would be included in the Committee’s report. The Committee agreed that further correspondence would be treated under the Osmotherly rules.

Agreed: Members agreed to embargo the report until 00.01am on 24 January 2008, when the report would be officially released.

Agreed: Members agreed not to hold a press conference to launch this report.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

18 October 2007

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

Also in attendance:

Mr John Dowdall CB |

Comptroller and Auditor General |

|

Mr David Thomson |

Treasury Officer of Accounts |

Witnesses:

Mr Iain Greenway |

Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland |

|

Mr Paul Sweeney |

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure |

1. The Chairperson (Mr O’Dowd):

I ask witnesses and members of the public to ensure that their mobile phones are turned off and not on silent mode; they interfere with the recording equipment. Today’s evidence session concerns internal fraud in the Ordnance Survey. Mr Paul Sweeney, who is the accounting officer for the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure, will give evidence. Mr Sweeney will introduce his colleague and outline his responsibilities.

2. Mr Paul Sweeney (Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure):

Good afternoon. My colleague is Mr Iain Greenway, who has been the chief executive of Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland since July 2006.

3. The Chairperson:

I will start the session with questions, and my colleagues will then be introduced to ask further questions. Evidence sessions usually take approximately two hours, although there is no fixed time limit.

4. I thank the witnesses for their attendance. The Audit Office report that we are examining today concentrates on a figure of approximately £70,000. Although that is by no means a massive amount of money in the context of the public purse, the Committee has chosen to examine the report because it views its subject matter as a case study and a reminder to other Departments that all financial proceedings for which they are responsible have to be properly managed and monitored.

5. The Committee acknowledges that the fraud that the report refers to was eventually detected, and a criminal prosecution resulted from that. However, prior to that fraud, the Ordnance Survey was the subject of another fraud a number of years ago.

6. The Committee wants to know the reasons that the lessons were not learnt from the first instance of fraud. When a Department, or an office of a Department, is dealing with finances, especially cash, there is always the possibility that fraud can occur. Why were the measures that were introduced after the first instance of fraud not imposed more stringently? Why did those measures not act either as a deterrent to the second instance of fraud or detect it at a much earlier stage?

7. Mr Sweeney:

It may be helpful if I were to differentiate between the two frauds. The first took place in 1988-91 in the map shop, and the second occurred in what I describe as a back-office context. The lessons that were learnt from and the recommendations that were made as a result of the first fraud were specific to the map shop enterprise.

8. Regrettably, insufficient connection was made between the proceedings in the map shop and the back-office, which was primarily responsible for cheque handling and credit control. Therefore, although a great deal of focus was on the map shop and cash reconciliation, there was a failure to make the connection between front-office and back-office functions.

9. The Chairperson: Both instances were similar in nature; they both involved cash flow through a Department. They both should have flagged up the same warning signals — any small business or any venture that has cash flowing through it always faces the possibility of fraud.

10. Therefore, although there may have been a physical and a duty separation, both frauds were similar. The recommendations that resulted from detection of the first fraud were relevant to the second. Therefore, are you saying that that was not the case, that there was a breakdown in communication or simply a breakdown in the system?

11. Mr Sweeney:

There is no doubt about that. I characterise the common features as follows: in both instances, there were serious shortcomings in the control framework in systems and procedures, and there was a failure to comply even when systems and procedures were in place. There was a failure of segregation of duties and a failure of management to provide adequate supervision. There was also serious failure in that no financial procedures manual was in place in either fraud. Therefore, there is no doubt, there were common features in both frauds, even though the degree and scale of fraud in the two were different.

12. Although lessons that were specific to the map shop and the cash reconciliation were learnt from the first fraud, with hindsight, insufficient effort was made to extrapolate those lessons into the back-office functions, where the more serious and substantive fraud took place.

13. The Chairperson:

The reason that I emphasise that is because this is a case study. I want to ensure that, when we publish our report, other Departments can look at it and that this is not dismissed as a case in which the individual involved has been arrested and prosecuted. The Committee feels that it is important that the report be drawn to the attention of other Departments in order that they know that although mistakes were made twice in the Ordnance Survey, other Departments could make similar mistakes. All Departments should, therefore, take heed of the report.

14. Moving on to a related subject, following the prosecution — or as a result of the prosecution — the court stipulated that approximately £70,000 had to be repaid by a certain date. Have those funds been recouped, or is a process in place to recoup them?

15. Mr Sweeney:

It was always the intention of the Department and the agency to seek full restitution. That decision was made in 2004. At the time, however, the best advice was to let the criminal case take its course first. That reached a conclusion in June 2006. Compensation of £30,000 was awarded in favour of the agency. That left a balance of approximately £40,000 to be recouped. Given our decision to seek full restitution, once the criminal case was over we commenced a civil action. We issued a writ in January 2007 for the repayment of £40,690. In response to that, we received a letter from the fraudster’s solicitors in February 2007. They indicated that there would be full restitution of the £40,690. The fraudster had undertaken to sell his family home, and full restitution would coincide with the date on which he was due to pay the original £30,000 compensation.

16. In July this year, we received two cheques from the fraudster through his agents. We received a cheque for £30,000, which was the compensation awarded by the court, and the £40,690, which resulted from the civil case that we brought in January. Therefore, full restitution of all the stolen funds has been achieved.

17. The Chairperson:

Are you saying that the fraudster had to sell the family home to make restitution?

18. Mr Sweeney:

We understand that his solicitor undertook in February to sell the house. Anecdotally, I am advised that that is indeed what happened. I do not want to show total disregard for the tragedy involved, but, in any event, the full sum has been repaid to the Department.

19. The Chairperson:

I do not want to minimise the theft of £70,000, but the fact that the fraudster had to sell his family home adds another tragic aspect to the story.

20. I should have stated at the start of the meeting that the Committee has two evidence sessions today in which it will deal with this case. After Mr Sweeney and Mr Greenway, the Committee will hear from Mr David Thomson of the Department of Finance and Personnel. That is information for members of the public who are present.

21. Members are free to ask questions. Mr Mickey Brady is the first questioner.

22. Mr Brady:

In 1999, shortly after the fraud began, the new chief executive allowed the finance manager to withdraw from day-to-day operations of the accounts branch. Can that be justified, given that the control environment may have been weakened at a time when there was a rapid growth in receipts?

23. Mr Sweeney:

There is no doubt that it cannot be justified. I have the company profile before me. The company’s turnover was increasing dramatically. There were staffing difficulties at the time, although that is not an excuse. A decision was taken to create that segregation. With hindsight, that was a serious mistake. The fact that turnover was increasing rapidly at the time is not a sufficient excuse; there were staff shortages, but they should have been addressed. Failure to address them created an environment in which fraud became more likely.

24. Mr Brady:

Was no provision made for the fact that a rapid growth had occurred? Was the intention that resources would be used to deal with that at a later stage?

25. Mr Sweeney:

Yes. The organisation — or agency — increased its income year-on-year from £1·5 million in 1997-98 to the current figure of approximately £10·7 million. The public had a phenomenal demand for OSNI services. Regrettably, there was not a commensurate increase in staff to catch up with that rapid demand for map sales.

26. Mr Brady:

Apart from the fraud, such a situation would, by definition, have put a lot more pressure on existing staff.

27. Mr Sweeney:

Yes.

28. Mr Iain Greenway (Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland):

With the permission of the Chairperson, I will provide more detail. As Mr Sweeney has outlined, the growth in revenues was significant and was part of an ongoing growth in ordnance survey as a Government entity. Much of that growth resulted from significant payments from other Government bodies for the use of mapping, and those payments took the form of a single cheque or a single financial transfer that went into OSNI’s bank account. Therefore, the growth in activity would not be directly proportionate to the growth in revenue because those large single payments flowed into bank accounts. In January 2004, the map shop took £25,000, which comprised £14,500 in cheques and £10,500 in cash. Although that is a snapshot, it is illustrative of a wider picture of the sort of amounts that were flowing into the map shop.

29. Mr Brady:

The report explains how the fraud was committed. Basically, Mr Steenson opened post on his own, removed cheques as he pleased and retained cash in his drawer. How was such an environment for cash handling allowed to develop, particularly as there had been a previous fraud?

30. Mr Sweeney:

The picture is one of an individual in his late forties who worked for the organisation for approximately 29 years. He worked in a financial role function since 1993. The report says that the fraud was not particularly sophisticated. The mechanics were such whereby the fraudster arrived at work between 7.30 am and 8.00 am each day, and he opened all the incoming post, which included cheques. Iain Greenway has already given a broad indication of how much was involved in any one month. Therefore, Mr Steenson was able to open the post and identify a number of cheques. He was also in receipt of the cash from the map shop. He stole the cash, replaced it with cheques, and drew fictitious credit notes for the debtors who had paid by cheque, and the money was lodged. In hindsight, that should never have been allowed to happen, as Mr Steenson was a credit controller. There was a failure of segregation of duties whereby he was able to open the cheques, reconcile the cash at the end of the day, and authorise credit notes, some of which he fabricated.

31. Mr Brady:

You said that the fraud was not sophisticated but that it was discovered only when Mr Steenson was on sick leave. Is there a possibility that had he not gone on sick leave, the fraud would not have been discovered and would have continued because he was in a position to cover his tracks?

32. Mr Sweeney:

The fraud in question was more sophisticated than the first fraud, which was very basic. There was a degree of cunning in the second fraud, in the sense that several activities were involved. Again, that was because the failure of segregation of duties led to the individual’s being able to manipulate a number of circumstances. There is no doubt that the situation’s coming to a head coincided with a serious period of illness for Mr Steenson.

33. There was a bad debt arrangement in the agency, and significant resources were put into addressing that problem. At that stage, it was noticed that irregularities were, regretfully occurring as far back as October 2002. With hindsight, there was some indication of irregularity. On balance, there is a good chance that the bad debt was being managed, and we were working to eradicate large bad debts down to smaller amounts. I believe that it was only ever going to be a matter of time before the discovery of the irregularities to do with the letters and telephone calls from customers who had sent cheques for which they were not credited. There is no doubt about that. However, those irregularities proceeded for several years before they were absolutely discovered.

34. Mr Brady:

There is a possibility that had the employee been on a short, rather than an extended, period of sick leave, the irregularities may not have been discovered.

35. Mr Sweeney:

There is that possibility. However, I am advised that it was inevitable that the irregularities on the management of the bad debt would be identified. I do not take any satisfaction from that, but it is possible that the crime would have been uncovered if Mr Steenson had not been off work.

36. Mr Brady:

The report lists a series of control failures, including inadequate segregation of duties and poor supervision. Do you consider those to be the most basic of controls? Who do you think is to blame for that complete lack of proper financial stewardship?

37. Mr Sweeney:

As I said at the beginning of the meeting, there was a control framework, and systems and procedures were in place. In hindsight, however, they were inadequate. Several internal audit exercises were carried out at the time, and a number of weaknesses was demonstrated. However, internal audit also identified how the agency adhered to several recommended practices for locking away cash, for instance. However, that was not always the case. There were some shortcomings in basic tasks: for example, one person opened the morning post, when the working practice presumed that there should have been two. There was, therefore, a failure to comply with systems and a failure of supervision.

38. Mr Brady:

It has already been mentioned that the sum of money involved was relatively small. However, the basic controls over larger amounts of money — payments from other agencies, for instance — might have been greater. Basic controls should be in place, irrespective of whether £20 or £70,000 is being sent to the agency. The controls were not in place to ensure that irregularities did not occur.

39. Mr Sweeney:

There were serious shortcomings in the control framework at the time. I am sure that we will go on to talk about the arrangements that are in place now. Strenuous efforts have been made to address those shortcomings, but when the two frauds were being perpetrated, there were serious shortcomings in the control framework and in the adherence to it.

40. Mr Craig:

I will continue in the same vein. Paragraph 12 on page 8 of the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report refers to a “lack of written financial procedures”. I know that the agency found itself in an interesting situation, given the rapid increase in the workload, but that inevitably leads to staffing issues. I am surprised that detailed written financial procedures were not in place, because it would have been a difficult situation to handle without them. In the absence of those procedures, how was anyone in the office supposed to recognise that illegal practices were taking place?

41. Mr Sweeney:

Various practices had built up in the office, but no comprehensive financial procedures manual was in place. For example, a core feature of such a manual would have provided a challenge function, through which other members of staff could have challenged what they considered to be shortcomings. A financial procedures manual that was accessible to all staff could have at least mitigated the circumstances in which this type of fraud was committed. A financial procedures manual should have been in place and available to all staff, but there was none, which was a serious shortcoming. That has subsequently been done, and it is updated regularly. Various audits have been carried out since then. The staff have been trained in the use of the manual and are adhering to it.

42. Mr Craig:

Paragraph 45 of the report states that the agency had not trained staff in fraud awareness. I found that surprising, given the fraud that occurred in 1991. Surely if any sort of fraud training had been provided to the staff it would have mitigated the extent of the second fraud. Are you aware of any reasons that no fraud training had been given in the wake of the 1991 incident?

43. Mr Sweeney:

As you know, central guidance had been made available in the agency from as early as 1998. The agency put in place a fraud policy in 2002, but it was not until 2004 that it developed a systematic approach to training staff in fraud awareness. I am not saying that there was complete ignorance of fraud in the organisation at the time, but the formal establishment of a fraud policy and a fraud response plan, with formal training for staff, did not happen until 2004 onwards.

44. Mr Craig:

Paragraph 46 of the report explains that although whistle-blowing legislation was enacted in 1999, the agency did not introduce a whistle-blowing policy until 2003. Does that explain the situation? I was surprised that the agency had not introduced that policy sooner.

45. Mr Sweeney:

Again, the fact that the agency did not adopt that policy until 2003 was a serious shortcoming.

46. Mr Craig:

Do you think that there was an element of complacency in the management of the incident at the time?

47. Mr Sweeney:

Members may feel that this is a self-serving statement, but the agency did some fine work. Its role and significance was growing, and as an exemplar in the public sector, it turned itself around from a loss-making concern into an organisation with a surplus of about £1·8 million this year. There is much in the organisation that is highly commendable. However, those two frauds — and this Audit Office report — have indicated that there was insufficient awareness of the management of fraud. There was certainly an over-reliance on the trustworthiness of one long-serving member of staff, who, all other things aside, had an unblemished performance record. There was a serious flaw in that that individual found a place in the line of command where there were vulnerabilities.

48. Mr Craig:

One can never fully guard against fraud, but are you satisfied that the procedures and awareness training that are now in place could potentially stop such an incident happening again?

49. Mr Sweeney:

It was true of the earlier fraud that several recommendations on basic cash reconciliation were almost immediately introduced, and so it was with the second fraud.

50. Internal audit played a very proactive role. A whole series of recommendations were identified and actions taken with regard to the control framework, and, in particular, the segregation of duties and the supervisory role. As a result of the work carried out by internal audit and by senior management within the agency, and the implementation of various policies and training programmes, there is much less chance of fraud being perpetrated again.

51. Mr Greenway:

It might help the Committee if I gave a feel for the range of controls that are now in place in OSNI. As Mr Sweeney mentioned, a seminar on managing fraud has been delivered to over 50 staff — all those in supervisory grades and above, and all those with responsibility for handling money. That is about a third of the agency’s staff. The seminar covered issues such as the nature of fraud, the warning signs of fraud and how to reduce the risk of fraudulent activity.

52. OSNI has a regularly revised fraud policy, a whistle-blowing policy and a fraud-response plan, and they are subject to annual review by the management board. As Mr Sweeney mentioned, there is a complete financial procedures manual, which goes into significant detail on handling everything through the accounts branch, and there is a parallel document in the map shop. They both detail procedures, but they also allow staff to have greater confidence to challenge what is happening in the office, if they feel that something is not being done correctly.

53. All senior managers have been trained in risk management. There is an annually reviewed risk-management policy. Fraud appears on OSNI’s risk register, which is regularly reviewed by the management board. The audit and risk management committee has been reconstituted; it now has a chairperson from outside OSNI. We have reviewed the terms of reference to ensure that they include anti-fraud and whistle-blowing matters.

54. We have appointed a security officer and we have a clear-desk policy, which is regularly reviewed through random checks carried out by Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure staff, who report back to the management board. As Mr Sweeney said, non-accounts staff now open the post — two staff members open all post and record all cheques. The banking for accounts branch and for the map shop are now carried out completely separately. Money is put into tamper-proof bags each day and taken to the bank by Securicor. Accounts branch has no access to cash, other than the minimal amounts in the petty cash float. All activities involving cash, raising credit notes and so on are subject to percentage checks by finance managers who do not have any involvement with those activities, as a result of segregation of duties.

55. There are pro formas for the raising of credit notes for journal entries, which must be counter-signed by at least two staff of managerial grade. The finance manager cannot raise credit notes, because he is responsible for some of the checking of those activities. The writing-off of bad debts has been formalised into a pro-forma system that requires at least two managerial signatures, so there has been a segregation of duties there as well. I hope that that helps the Committee to get a feel for the range of responses that OSNI has tightened and reviewed — and continues to regularly review — with assistance from internal audit.

56. Mr Beggs:

A PAC report in 2002 dealt with similar frauds in the finance branch of the Local Enterprise Development Unit (LEDU). It identified inadequate separation of duties and poor supervision as the main control weaknesses. It is disturbing to see those same mistakes repeated. Mr Sweeney, what actions did your Department and its agencies take on receiving that PAC report in 2002? How did you learn the lessons from that?

57. Mr Sweeney:

I can only outline what I imagine would have happened in the Department at that time, based on what happens with all PAC reports. Such reports are cascaded down through the Department, with the presumption that people will read them and learn lessons from them. On two occasions, our organisation has used the OSNI fraud as a case study in working with senior management and external bodies.

58. To return to your specific question, Mr Beggs, beyond my presumption that that report would have been cascaded down through the organisation and an obligation placed on senior management to take on board the lessons learnt, I cannot be more specific. I cannot say what specific steps the Department and the agency took in 2002 in respect of the LEDU case.

59. Mr Beggs:

Do you accept that, if management had read and understood that report, the subsequent fraud would not have occurred?

60. Mr Sweeney:

I cannot give that guarantee.

61. Mr Beggs:

Is it likely that, if the recommendations about the segregation of duties and other issues had been implemented and the management had developed a better understanding of their responsibilities, the fraud would have been detected earlier?

62. Mr Sweeney:

My view is that an over-reliance on that long-serving individual and a failure to segregate duties were ingrained practices in the modus operandi of OSNI. Even if the lessons from the report on the fraud in LEDU had been fully taken on board, I cannot guarantee that this instance would have been avoided. One would like to think that that should have been the case, but there was misplaced over-reliance on the trustworthiness of an individual.

63. Mr Beggs:

Figure 2 and appendix 1 of the report show that there are a number of lessons to be learnt from this case. Can you summarise what you think those key lessons are?

64. Mr Sweeney:

The overarching lesson is, simply, that fraud will not be tolerated, and when fraud is perpetrated, the full rigour of the law should be brought to bear. No officer should be given the impression that there is a lackadaisical attitude to fraud.

65. Beyond those overarching lessons, the core characteristics of the fraud that I would identify are: a failure to comply with the systems that were in place; a failure of supervision; a failure to segregate duties; and, of course, the absence of a financial procedures manual, which was a particular shortcoming in this instance.

66. Mr Beggs:

Are you satisfied that those lessons have been circulated as widely as possible in the Department, to other relevant agencies, and, indeed, to other Departments?

67. Mr Sweeney:

Several steps have been taken. Apart from the measures that Mr Greenway outlined, which relate specifically to OSNI, in 2004, the then permanent secretary of the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure brought together the Department’s senior managers and the NDPBs and arm’s-length bodies for which the Department is responsible. The OSNI fraud was used as a case study, and the circumstances that gave rise to it, the lessons that were learned and the steps that have been taken were considered. That was important — important enough for me to repeat the exercise last year. In September 2006, I brought together the Department’s senior finance personnel and the people responsible for financial accountability in the arm’s-length bodies, and, again, we used the OSNI fraud as a case study in order to learn lessons.

68. Further to those actions, other steps were taken. Recently, I conducted a governance and accountability audit of all the external bodies for which the Department is responsible. I sought to identify areas of risk and weakness and, in particular, to zone in on those bodies’ fraud policies and their risk-management systems relating to fraud. That exercise has been completed.

69. Finally, to bring you completely up to date, I recently asked internal audit to independently assess the Department’s management of fraud, and it has been rated as satisfactory.

70. Mr Beggs:

This discussion has been about the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. Have the lessons learned in the LEDU and OSNI cases been grasped by other Departments and agencies, in order to prevent similar cases in the future?

71. Mr David Thomson (Treasury Officer of Accounts):

Perhaps there will be an opportunity for me to discuss this with the Committee later on. This is one of the topics that have been discussed at the fraud forum.

72. Mr Beggs:

Paragraph 42 of the report refers to a review in March 2004. It is noted that only 77% of the significant recommendations made following the fraud had been implemented. That means that 23% of the recommendations had not been implemented after a period of seven months. Which recommendations were not implemented promptly — and why?

73. Mr Sweeney:

All of the recommendations were acted on. However, by that stage — March 2004 — only 77% had been fully implemented. There were seven areas where a number of recommendations had not been fully implemented. If it helps the member, I can go through each of those seven areas. Shall I do that?

74. Mr Beggs:

Yes, please.

75. Mr Sweeney:

First of all, a security officer for the building had not been appointed by March 2004. Mr Greenway has already mentioned the security officer. There were no formal records of when staff discounts had been applied. I have been advised that, in fact, they were in place, but the auditors at that time had not picked up that fact. There was an issue as regards to the credit-card swipe machine, which was not yet able to blank out the last three digits on a till receipt. I am advised that it was not feasible to do that at that time. There was a shortcoming as regards to general journal entries, in that there was an inadequate separation of duties. The issue of petty cash remained outstanding at that time. There was also an issue about the location of debt management staff. There was a suggestion that staff should be separated from each other and that posts should be regularly rotated. However, it was later agreed with internal audit that there was no need for that recommendation to be implemented.

76. I want to assure the Committee member that — although only 77% of the recommendations had been fully implemented at that stage — all of the recommendations were being acted on. When a full compliance audit was conducted in September 2006, 100% of the recommendations that could feasibly be implemented had been implemented.

77. Mr Beggs:

Are you saying that seven months after a review which identified some issues that are pertinent to the case, those issues had not been acted on — journal entries, separation of duties? Why had they not been implemented? Is that not the responsibility of management?

78. Mr Sweeney:

In some instances it turned out that it was not feasible to enact them. That was the case with the credit-card swipe machine. In some instances, internal audit subsequently agreed that the recommendation did not have to be acted on. Action was being taken in other areas, such as the appointment of a security officer. By March 2004, the security officer had not been appointed, but subsequently that person was appointed. I must assure the Committee member that all the recommendations were being acted on. The fact was that, by the time of the interim compliance check, not all of the recommendations had been 100% implemented.

79. Mr Beggs:

In paragraph 44 of the report, the Northern Ireland Audit Office states that you:

“placed a high degree of reliance on the ongoing positive reports from internal and external audit.”

80. Is that not a basic misunderstanding of the role of the audit process and the responsibility that falls on management? Management should not rely on an external audit to say that all is well and should delve into everything. Do you accept that you and your Department have placed too much reliance on the audit process?

81. Mr Sweeney:

I concur with the member’s opinion. The function and role of internal audit is to assist senior management in discharging their responsibilities. However, it should be only one of the mechanisms that senior management brings to bear as a means of satisfying itself about the appropriateness of the control framework. I do not want to give the impression that those two fraudsters were able to do what they did because internal audit let down the Department and the agency. That is not the case. Internal audit, in my experience, generally provides a very good service. However, it is only one of senior management’s functions that may be brought to bear when discharging their accountability responsibilities.

82. As Iain Greenway said, a number of steps have been taken to beef up the role of the audit and risk management committee in the agency, including the appointment of an external chairperson. The deputy secretary of the Department now sits on that committee. I do not wish to apportion blame to internal audit for what happened in OSNI.

83. Mr Beggs:

Who is to blame? Public money was fraudulently removed from the agency: who is to blame? You said that neither management nor internal audit is to blame. This was public money: who is to blame?

84. Mr Sweeney:

On reflection, and having read the report, there were serious shortcomings in the control framework, in systems and procedures, in compliance and in the segregation of duties. Excessive trust was placed in one individual, and a financial procedures manual was not in place. Those were serious shortcomings.

85. Mr Hamilton:

You said that there was perhaps an inevitability in detecting the fraud, because of the nature of it, and that there was a possibility, even without extended sick leave, that the fraud might have been detected. Paragraphs 30 to 35 of the report highlight some clear, consistent warning signals that showed that the fraud should have been detected earlier. There were inconsistencies in the debtors report. There were a series of customer complaints and a general problem of one individual opening the post. If those warning signals had been acted on, could the fraud have been detected earlier?

86. Mr Sweeney: