Session 2007/2008

Fourth Report

Public Accounts Committee

Report on the Transfer of

Surplus Land in the PFI Education Pathfinder Projects

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE

RELATING TO THE REPORT AND THE MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

Ordered by Public Accounts Committee to be printed 22 November 2007

Report: 11/07/08R (Public Accounts Committee)

PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY

BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE

£12.50

Public Accounts Committee

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts and reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 51 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson) Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson) |

|

| Mr Willie Clarke* Mr Jonathan Craig Mr John Dallat Mr Simon Hamilton Mr David Hilditch |

Mr Trevor Lunn Mr Patsy McGlone Mr Mitchel McLaughlin Ms Dawn Purvis |

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke on 1st October 2007

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report

Report

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

Introduction

Maximising the Value and Use of Surplus Assets

Obtaining Market Value for Surplus Assets

Protecting the Public Sector’s Interests

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2:

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3:

Correspondence

Appendix 4:

List of Witnesses

List of Abbreviations

used in the Report

The Department Department of Education

Board Belfast Education and Library Board

PAC Public Accounts Committee

SLAs Surplus Land Agreements

BIFHE Belfast Institute of Further and Higher Education

IT Information Technology

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

SIB Strategic Investment Board

PUK Partnerships UK

VLA Valuation and Lands Agency

DEL Department for Employment and Learning

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

PPP Public Private Partnership

CMT Contractor Monetary Threshold

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. Between June 1999 and October 2000 five contracts were let for six Education PFI Pathfinder projects comprising four schools and two further and higher education colleges. Four of the five contracts contained clauses dealing with the transfer of surplus assets from the public sector to PFI operators. The value agreed, through negotiation, for these surplus assets was over £23 million.

2. Wellington/Balmoral was the most significant of these contracts and formed the basis for the Committee’s evidence session, which was held at Wellington College. This was the first time the Committee has gone out to the community for an evidence session and it wishes to record its appreciation for the time and effort taken by the Board of Governors, Principal, staff and pupils to facilitate the Committee.

3. The Committee recognises that these were pathfinder projects and that the Department of Education (the Department) was in the position of having to pioneer and develop the contracts through complex negotiation with the private sector developers. The Committee also notes that both the Department of Education and Department for Employment and Learning believe they have learnt a lot and gained from the experience both now recognising that the inclusion of land can unnecessarily complicate a scheme.

4. However the Committee considers that the complexity of the Pathfinder contracts and negotiations were self-imposed through the Department and, in particular, the Belfast Education and Library Board’s (the Board) assumption that the inclusion of land would lead to better quality bids, better added value in the overall quality of schools and colleges and their desire to use the receipts in a way that made the projects more affordable. The Committee also considers that the Department’s rush to deliver these schemes added further to their complexity and weakened the public sector’s ability to negotiate a good deal, a key factor which was exploited by the private sector.

5. While the Committee accepts that much needed, and indeed long overdue new facilities were provided and that some clawback has been secured, it does not accept that, in practice, the Pathfinder projects have delivered real value for money. In particular, the Committee considers that, with proper foresight, the Balmoral project could, and should have been avoided. The Committee awaits with interest the outcome of the Department’s and Board’s deliberations over this school’s future use after its closure at the end of August 2008. The Committee expects the Department to ensure that the negotiations with the operator are more successful and beneficial to the taxpayer than those surrounding the original contract and its outworking.

Maximising the Value and Use of Surplus Assets

6. Given a choice, the preference of the Valuation and Lands Agency (VLA) — now known as Land and Property Services — was to have sold the land on the open market, but this option could not be pursued because of the restrictions of the PFI contract. However, it is not clear to the Committee why, particularly in relation to the Wellington/Balmoral contract, the Department had to include the land in the PFI deal. If the reason was that the sale would have meant surrendering all or a significant proportion of receipts to the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP), the outcome in terms of loss of income from the sale and the additional costs in setting up and managing the PFI contract, have been substantial. In addition, maximising the value of land in advance of negotiations through, for example, obtaining enhanced planning permission, may have strengthened the Departments’ and Boards’ negotiating position in these deals. As a result of the approach taken it is difficult for the Department to demonstrate, and for this Committee to assess, whether the proceeds from the transfer of the land were maximised.

7. There were pressures on the education authorities to provide educational accommodation for young people that is appropriate to their learning needs. However, the Committee questions why steps had not been taken much earlier to provide, for example, Wellington College with a building that was fit for purpose. The Board’s failure to address these problems earlier only added to the time pressures it found itself facing during negotiations. This has been a key factor limiting its ability to negotiate a good deal for the public purse. This also highlights a frequent lesson emerging from Public Accounts Committee (PAC) reports that the public sector must be careful to avoid being time constrained when dealing with the private sector.

8. The Department made repeated assertions that the objective of the Surplus Land Agreements (SLAs) was to recover the value of the land. However, it is clear that the Department was perfectly aware that the developers were looking at planning proposals and that the land would be further developed. Therefore the Department of Education was selling a development potential — not simply land.

Obtaining Market Value for Surplus Assets

9. The Committee does not accept that the Department has obtained value for money from the sale of the Rosetta site. The Committee is astounded that the land was transferred to the developer without being measured, resulting in the developer gaining an extra half acre of prime land for residential development (worth an estimated £400,000) over and above the one acre agreed.

10. The Department seems to have made a broad brush judgement that the Rosetta land transfer provided “reasonable value for money in the overall bid”. This was not supported with a rigorous assessment of the financial costs or benefits. That is not good enough. It is an Accounting Officer’s responsibility to ensure that they can demonstrate that they have secured best value for the disposal of surplus assets. That could not be done in this case.

11. The Committee is astonished that the Board, having put together a team of advisors to ensure that it was given the best advice in any decision it undertook, failed to utilise the VLA’s expertise. The excuse given by the Board’s Accounting Officer that, in the heat of discussions and negotiations such things are overlooked, demonstrates, in the Committee’s view, a lack of judgement bordering on negligence. It is clear from the report that the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) has serious concerns over the value for money achieved for this site — a concern that is shared by this Committee.

12. A key lesson emerging from these projects is the need to be able to carry out negotiations effectively. The Department accepts that the Pathfinder projects were under-resourced and that the Departmental team was too small, resulting in the heavy use of consultants. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee is concerned that the team did not seem to have had the skills to match the private sector negotiators.

Protecting the Public Sector’s Interests

13. With regard to the Tillie and Henderson site, the Department was in possession of an asset that it valued at £750,000. Two years later, that asset was transferred to a developer for that price, then sold in a matter of weeks, for £925,000, delivering a profit of 23%. It is also clear that the clawback arrangements put in place were defective.

14. In relation to the Wellington/Balmoral and Belfast Institute of Further and Higher Education (BIFHE) — now known as the Belfast Metropolitan College — sites, provisions were included in the SLAs to protect the public sector’s interest from the sale of undeveloped surplus land or the development of the sites. However, the SLAs only recouped some of the funds that were estimated because of the way in which the Department had to do the deal at the time.

15. The Committee is concerned about statements made to the previous Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Finance and Personnel that “income or profit” realised by a private developer would be shared with the public sector. There seems to have been a significant change in thinking since that submission, to the Department’s current view that the objective of the SLA process was about recovering the value of the land. The Committee does not share this perspective. In the four contracts examined, it is clear that the surplus assets have been transferred to the private sector operators at less than market value and it took six years for the public sector to recover little more than this for the sites. This also has to be considered in the context of a flourishing property market in Northern Ireland over this period e.g. BIFHE’s Ormeau site has seen an estimated increase in value of £3.8 million or 120% over the last five years.

16. The Committee notes that the Business Case for the project estimated the potential income share on a fully developed site to be around £10 million. However, by transferring the land to a connected party, the developer outflanked the Board and has removed any potential gains for the public sector that may have accrued from the ongoing development of the Wellington and Balmoral sites. The Committee views this as a fundamental flaw in the SLA and is deeply concerned that this issue was not properly addressed. Furthermore, the Committee is concerned that a “commercial decision” was taken not to pursue amounts due to the Board relating to extras, such as bathroom suites, kitchens etc, included in developed properties on the Wellington site. This would appear to be another example of the use of ambiguous terms in an agreement, with the result that the public sector has lost out and settled for less than it should have.

17. The Committee is disappointed that the Department’s Building Handbook has not been revised since 2003 and that recommendations contained in the NIAO report, “Building Schools for the Future”, have not yet been incorporated. The need to revise the Handbook is also clear from the facilities at Wellington.

18. From the evidence presented there must be a concern that, in the Wellington and Balmoral projects, the developer was more interested in securing the maximum amount of land for development. All the negotiations centred around the value of the land and what more could be squeezed out from the sites. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Department has accepted there may have been better ways of carrying out such a project.

Summary of Recommendations

Maximising the Value and Use of Surplus Assets

1. The Committee recommends that, before making a decision on disposal of surplus assets, public sector bodies must properly assess the contribution those assets may make to the achievement of other strategic priorities and objectives.

2. Where a decision is taken to dispose of surplus assets, the Committee recommends that public sector bodies must carefully assess the relative returns and priority between their inclusion in a deal and conventional disposal. However, regardless of the chosen method of disposal they must be able to demonstrate that they have obtained best value for the asset.

3. The Committee recommends that when considering the disposal of a site, public bodies must adhere to the basic principles of defining the site precisely and valuing it accordingly. Public bodies must also ensure that they engage the Land and Property Service, and where appropriate recognised professional valuers, from the outset and ensure that valuations are updated on a regular basis.

4. The Committee recommends that public sector bodies must ensure that contracts are properly structured with penalty clauses and conditions which secure the prompt payment of monies due to them.

5. The Committee recommends that when disposing of assets Departments should develop and adhere to a clear marketing strategy which considers all aspects of the deal and identifies the key risks to be managed, including avoiding being time-constrained in their dealings with the private sector.

6. It has been recognised that there can be a valuable incentive in allowing departments, within limitations, to retain receipts. The Committee expects the Department of Finance and Personnel to respond sympathetically in priority areas, where a business case can be produced which demonstrates the maximisation of receipts and value for money for the public purse.

Obtaining Market Value for Surplus Assets

7. It is important that public bodies have systems in place to monitor and assess the quality of advice provided by their advisors. The Committee recommends that where there is clear evidence that the advice or support provided by consultants has not met the standards required and has resulted in a loss to the public purse, appropriate action is taken to recover fees paid and losses incurred.

8. A key requirement for public bodies in disposing of assets is to maximise the return to the public purse. The Committee recognises that there are risks and costs associated with obtaining planning permission. However, we recommend that at least outline planning permission should be obtained where it is likely to benefit the return to the public purse.

9. The Committee recommends that in taking forward major projects that require negotiations with the private sector, the public sector team must be adequately resourced and have the required experience, expertise and skills to at least match those of the private sector. Where external advisors are engaged it is also important that their experience and skills are similarly up to the mark.

Protecting the Public Sector’s Interests

10. The Committee recommends that clawback agreements agreed with the private sector should ensure that the interests of the taxpayer are fully protected. Those clawback provisions must be watertight and fully address the legal position regarding the sale or transfer of assets to ensure that such sales or transfers will not go against or disadvantage the public sector.

11. Public bodies must learn the lessons from these cases when agreeing contract provisions such as “Contractor Monetary Thresholds” and “extras” and ensure that they are comprehensive and transparent. The Committee recommends that it is important to ensure that, as far as possible, a standard approach is applied in the drawing up of such contract provisions.

12. The Committee recommends that clawback provisions should address the public sector’s long term interests and emphasises the importance of preserving its rights to share in future development gains or profits arising following the sale or transfer of assets to connected parties.

13. The Committee was critical that post project evaluations are not always carried out despite departmental guidelines. The Committee recommends that post project evaluations are always carried out and finalised as a matter of urgency.

14. The Department of Education should undertake a fundamental review of the current Building Handbooks to ensure they reflect the lessons learned from the post project evaluations and the findings of the NIAO report. The Committee also recommends that the revision of these Handbooks should involve the engagement of key stakeholders including principals, senior teachers and governors.

15. The Committee is dismayed by the closure of Balmoral High School only six years after it opened in 2002. It is evident that the Department faces a major challenge in managing school provision in the context of reducing enrolments across Northern Ireland. However, it is vital that finding a solution to this problem remains high on the Department’s priorities and that the lessons from the Balmoral experience are learned.

16. The Committee recommends that such unnecessarily complex arrangements are avoided in future. More generally, when governance arrangements are agreed, they should be properly applied.

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee met on 4 October 2007 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report: “Transfer of Surplus Land in the PFI Education Pathfinder Projects” (NIA 21, Session 2007-08). The witnesses were:

- Mr Will Haire, Accounting Officer, Department of Education.

- Mr Eugene Rooney, Development and Infrastructure Division, Department of Education.

- Mr David Cargo, Chief Executive, Belfast Education and Library Board.

- Mr Tom Redmond, Head of Further Education Estates, Department for Employment and Learning.

- Mr Stephen Halliday, Senior Valuer, Land and Property Services, Department of Finance and Personnel.

- Mr John Dowdall CB, Comptroller and Auditor General.

- Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee also took written evidence from Mr Haire, Mr Redmond, Mr Halliday and Wellington College Board of Governors.

2. Between June 1999 and October 2000 five contracts were let for six Education PFI Pathfinder projects comprising four schools and two further and higher education colleges. Four of the five contracts contained clauses dealing with the transfer of surplus assets from the public sector to PFI operators. The value agreed, through negotiation, for these surplus assets was over £23 million.

3. The Committee recognises that these were pathfinder projects and that the Department was in the position of having to pioneer and develop the contracts through complex negotiation with the private sector developers. The Committee also notes that both the Department of Education and Department for Employment and Learning believe they have learnt a lot and gained from the experience, both now recognising that the inclusion of land can unnecessarily complicate a scheme.

4. However the Committee considers that the complexity of the Pathfinder contracts and negotiations were self-imposed through the Department and Boards’ assumption that the inclusion of land would lead to better quality bids, better added value in the overall quality of schools and colleges and their desire to use the receipts in a way that made the projects more affordable. The Committee also considers that the Department’s rush to deliver these schemes added further to their complexity and weakened the public sector’s ability to negotiate a good deal, a key factor which was exploited by the private sector.

5. While the Committee accepts that much needed, and indeed long overdue new facilities were provided and that some clawback has been secured, it does not accept that, in practice, the Pathfinder projects have delivered real value for money. In particular, the Committee considers that, with proper foresight, the Balmoral project could, and should have been avoided. The Committee awaits with interest the outcome of the Department’s and Board’s deliberations over this school’s future use after its closure at the end of August 2008. The Committee expects the Department to ensure that the negotiations with the operator are more successful and beneficial to the taxpayer than those surrounding the original contract and its outworking.

6. In taking evidence, the Committee focussed on the following issues:

- the need for Public Bodies to ensure that the best use is made of surplus assets and receipts from sales or transfers is maximised;

- the need for Public Bodies to obtain market value for surplus assets; and

- the importance of putting effective controls in place to protect public sector interests.

Maximising the Value and Use

of Surplus Assets

7. It is clear that, given a choice the preference of the VLA was to have sold the land on the open market, but it was unable to do that because of the restrictions of the PFI contract. However the overall impression gained by the Committee is that neither the Department nor the Board had due regard to the VLA’s advice, only engaging them as and when it suited and not always when required. This resulted in VLA having to develop a methodology for clawback which it described as a “measure of last resort”. Because of the approach taken it is difficult for the Department to demonstrate and for this Committee to assess, whether the proceeds from the transfer of the land were maximised. The Committee welcomes the Department’s acceptance that it is much easier to demonstrate that value for money has been achieved through an open market disposal.

8. The Department accepts that it took a conscious decision not to forward details of the surplus lands to the VLA, despite there being a clear requirement to do so. The Committee is highly critical of the fact that a department can so readily set aside a requirement such as this.

Recommendation 1

9. The Committee recommends that, before making a decision on disposal of surplus assets, public sector bodies must properly assess the contribution those assets may make to the achievement of other strategic priorities and objectives.

Recommendation 2

10. Where a decision is taken to dispose of surplus assets, the Committee recommends that public sector bodies must carefully assess the relative returns and priority between their inclusion in a deal and conventional disposal. However, regardless of the chosen method of disposal they must also be able to demonstrate that they have obtained best value for the asset.

11. There were pressures on the education authorities to provide educational accommodation for young people that is appropriate to their learning needs. The Committee acknowledges that the Department was anxious to proceed with the development of these schools and colleges. However, it questions why steps had not been taken much earlier to provide, for example, Wellington College with a building that was fit for purpose, particularly when the previous building was described as an “education slum.” The Board’s failure to address these problems earlier only added to the time pressures it found itself facing during negotiations. This has been a key factor limiting its ability to negotiate a good deal for the public purse through, for example, ensuring that up to date valuations were obtained. In addition, while negotiations will always involve balancing speed and closure with prudence, it does not obviate the need to apply the basic principles, such as adhering to DFP Guidance, of defining the site precisely and valuing it accordingly, using recognised professional valuers.

Recommendation 3

12. The Committee recommends that when considering the disposal of a site, public bodies must adhere to the basic principles of defining the site precisely and valuing it accordingly. Public bodies must also ensure that they engage the Land and Property Service, and where appropriate recognised professional valuers, from the outset and ensure that valuations are updated on a regular basis.

13. A frequent lesson emerging from PAC reports is that the public sector must be careful to avoid being time constrained when dealing with the private sector. A clear example of this is the Board’s handling of the plot of land adjacent to the Balmoral site, which became an integral part of discussions about the site. The public sector bodies involved sought to achieve, what was described as, the optimum return as there was a perceived risk that the clawback agreed for the Balmoral site would be reduced. It is clear to the Committee that this small plot of land was important to the developer and as such should have attracted a much higher value, reflecting its key land status. In addition, the failure to have a properly structured contract, with penalty clauses and conditions written into it effectively led, in the Committee’s view, to the Board being held to ransom.

Recommendation 4

14. The Committee recommends that public sector bodies must ensure that contracts are properly structured with penalty clauses and conditions that secure the prompt payment of monies due to them.

15. The Department made repeated assertions that the objective of the SLAs was to recover the value of the land. However, it is clear that the Department was perfectly aware that the developers were looking at planning proposals and that the land would be further developed. Therefore the Department of Education was selling a development potential — not simply land.

Recommendation 5

16. The Committee recommends that when disposing of assets Departments should develop and adhere to a clear marketing strategy which considers all aspects of the deal and identifies the key risks to be managed, including avoiding being time constrained in their dealings with the private sector.

17. Where surplus assets are to be sold, the ability to retain receipts can act as an incentive to public bodies to maximise income generation. The potential benefits to be derived from this approach are demonstrated in the Department for Employment and Learning’s, Belfast, Lisburn and East Down Institute Public Private Partnership projects, where the capital amount will be raised from the sale of land on the open market.

18. It is not clear to the Committee why, particularly in relation to the Wellington/Balmoral contract, the Department had to include the land in the PFI deal. If the reason was that the sale would have meant surrendering all or a significant proportion of receipts to the DFP, the outcome in terms of loss of income from the sale and the additional costs in setting up and managing the PFI contract, have been substantial.

Recommendation 6

19. It has been recognised that there can be a valuable incentive in allowing departments, within limitations, to retain receipts. The Committee expects the Department of Finance and Personnel to respond sympathetically in priority areas, where a business case can be produced which demonstrates the maximisation of receipts and value for money for the public purse.

Obtaining Market Value for

Surplus Assets

20. The Committee does not accept that the Department has obtained value for money from the sale of the Rosetta site. The Committee is particularly concerned that the Board’s financial consultants started negotiations with private developers without engaging the expert advice of the VLA. The trouble was that they started off on the basis that only one acre of land at Rosetta was being sold off. The Committee is astounded and appalled that the land was transferred to the developer without being measured, resulting in the developer gaining an extra half acre of prime land for residential development (worth an estimated £400,000) over and above the one acre agreed. The VLA confirmed to the Committee that, had it been asked, they would have applied best practice and measured the site.

21. The Committee asked the Department for details to support their assessment that the Rosetta land transfer in exchange for the provision of a floodlit all weather pitch and the enlarged sports hall, provided “reasonable value for money in the overall bid”. This seems to have been a broad brush judgement which was not clearly analysed and defined and was not supported with a rigorous assessment of the financial costs or benefits. That is not good enough. It is an Accounting Officer’s responsibility to ensure that they can demonstrate that they have secured best value for the disposal of surplus assets. That could not be done in this case.

22. The Committee is astonished that the Board, having put together a team of advisors to ensure that it was given the best advice in any decision they undertook, failed to utilise the VLA’s expertise. The excuse given by the Board’s Accounting Officer that, in the heat of discussions and negotiations such things are overlooked demonstrates, in the Committee’s view, a lack of judgement bordering on negligence. It is exactly at such times that expert advice is required and should be sought. The VLA should have been brought into the process at that time and matters should have been dealt with more clearly and more openly.

23. Given the extent of the Board’s reliance on its financial consultants in the Rosetta dealings, and the issues that have come to light surrounding the measurement and valuation of the site, the Committee rejects the Board’s assertion that it would be difficult to go back to its advisors and tell them that, in this instance, they failed. The Committee also rejects the contention of the Board’s Accounting Officer, when pressed on the subject, that “in a sense, the Audit Office acknowledges that the actual price that we got for the land was better than its estimated worth”. It is clear from the report that the NIAO has serious concerns over the value for money achieved for this site – a concern that is shared by this Committee.

Recommendation 7

24. It is important that public bodies have systems in place to monitor and assess the quality of advice provided by their advisors. The Committee recommends that, where there is clear evidence that the advice or support provided by consultants has not met the standards required and has resulted in a loss to the public purse, appropriate action is taken to recover fees paid and losses incurred.

25. Maximising the value of land in advance of negotiations through, for example, obtaining enhanced planning permission, may have strengthened the Departments’ and Boards’ negotiating position in these deals. Negotiations based on an assumption that planning permission is in place are no substitute; developers will, as shown in the Wellington/Balmoral project, protect themselves against the risk of not obtaining planning permission, by offering a lower value. In turn, there is a real risk that this may result in the public sector not receiving the full benefit of any uplift in value from the enhanced planning permission.

Recommendation 8

26. A key requirement for public bodies when disposing of assets is to maximise the return to the public purse. The Committee recognises that there are risks and costs associated with obtaining planning permission. However, we recommend that at least outline planning permission should be obtained where it is likely to benefit the return to the public purse.

27. A key lesson emerging from these projects is the need to be able to carry out negotiations effectively. The Department accepts that the Pathfinder projects were under-resourced and that the Departmental team was too small, resulting in the heavy use of consultants. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee is concerned that the team did not seem to have had the skills to match the private sector negotiators.

Recommendation 9

28. The Committee recommends that in taking forward major projects that require negotiations with the private sector, the public sector team must be adequately resourced and have the required experience, expertise and skills to at least match those of the private sector. Where external advisors are engaged it is also important that their experience and skills are similarly up to the mark.

Protecting the Public Sector’s Interests

29. The Committee does not accept that the complexity of the PFI process is a valid reason for not basing negotiations on up to date valuations for the Tillie and Henderson site. The Department was in possession of an asset that it valued at £750,000. Two years later, that asset was transferred to a developer for that price, then sold in a matter of weeks, for £925,000, delivering a profit of 23%.

Recommendation 10

30. The Committee recommends that clawback agreements agreed with the private sector should ensure that the interests of the taxpayer are fully protected. Those clawback provisions must be watertight and fully address the legal position regarding the sale or transfer of assets to ensure that such sales or transfers will not go against or disadvantage the public sector.

31. It is clear to this Committee that the clawback arrangements put in place for the Tillie and Henderson sites were defective. It is interesting that despite the rapid increase in value after sale, the threshold for triggering clawback was barely achieved. Furthermore, the reasons provided by the Department for not pursuing clawback from the operator, on the grounds that he would have incurred additional expenses, are wholly inadequate. Indeed, the very intention of the Contractor Monetary Threshold should be to provide for such expenses.

32. The Committee is concerned that a “commercial decision” was taken not to pursue amounts due to the Board relating to extras, such as bathroom suites, kitchens etc, included in developed properties on the Wellington site. This would appear to be another example of the use of ambiguous terms in an agreement, with the result that the public sector has lost out and settled for less than it should have.

Recommendation 11

33. Public bodies must learn the lessons from these cases when agreeing contract provisions such as “Contractor Monetary Thresholds” and “extras” and ensure that they are comprehensive and transparent. The Committee recommends that it is important to ensure that, as far as possible, a standard approach is applied in the drawing up of such contract provisions.

34. In relation to the Wellington/Balmoral and BIFHE sites, provisions were included in the SLAs to protect the public sector’s interest from the sale of undeveloped surplus land or the development of the sites. The view expressed by the witnesses is that the SLAs worked and gave a reasonable return. However, it also emerges that the SLAs only recouped some of the funds that were estimated because of the way in which the Department had to do the deal at the time.

35. The Committee is concerned about statements made to the previous Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Finance and Personnel that “income or profit” realised by a private developer would be shared with the public sector. There seems to have been a significant change in thinking since that submission, to the Department’s current view that the objective of the SLA process was about recovering the value of the land. The Committee does not share this perspective. The Agreement clearly contained provision for the development of the site and a sharing of those development gains with the Board. This is evident both from the NIAO report and the Department’s supplementary evidence which indicates that “income” is related to actual house sales receipts obtained by the developer i.e. his gross turnover. Indeed over half of the final £3 million clawback received for the Wellington site was in respect of the developed portion of the site. The Committee considers that, by definition, a reasonable interpretation of income includes developer’s profit.

36. In the four contracts examined, it is clear that the surplus assets have been transferred to the private sector operators at less than market value, the shortfall being around £4.2 million. The Department’s argument that clawback of £3.8 million in the Wellington/Balmoral sites, achieved through the SLAs, has rebalanced public value, disguises the fact that it took six years for the public sector to recover little more than the original market value for the sites. This also has to be considered in the context of a flourishing property market in Northern Ireland over this period. This is demonstrated in the VLA’s estimate of the increase in the market value of similar land transferred by BIFHE at the Ormeau Embankment, which has seen an increase in value of £3.8 million or 120% over the last five years.

37. The Committee notes that a value for money assessment paper supporting the Business Case for the project, estimated the potential income share on a fully developed site to be around £10 million. This was considered to be a conservative estimate and given the significant increase in the value of similar sites and Northern Ireland property prices, has indeed proven to be so. The issue that concerns the Committee is that by transferring the land to a connected party, the developer outflanked the Board and has removed any potential gains for the public sector that may have accrued from the ongoing development of the Wellington and Balmoral sites. The Committee notes that the sale to a connected party was one of the scenarios that concerned the Board from the outset and views this as a fundamental flaw in the SLA. The Committee is deeply concerned that this issue was not properly addressed and the Department appeared to be complacent about it.

38. In agreeing the settlement of clawback on the Balmoral site, the Committee notes, from the supplementary evidence provided by Land and Property Services, that a potential range of values for the site, by the Board’s independent valuer, was between £5 million and £6.6 million with a most likely value of £5.5 million. However, the Board agreed to base clawback on the lower negotiated value of £5 million so the transfer could be effected quickly. Had the higher valuations been used, the clawback received could have been in the range of £1.1 million to £1.8 million.

Recommendation 12

39. The Committee recommends that clawback provisions should address the public sector’s long term interests and emphasises the importance of preserving its rights to share in future development gains or profits arising following the sale or transfer of assets to connected parties.

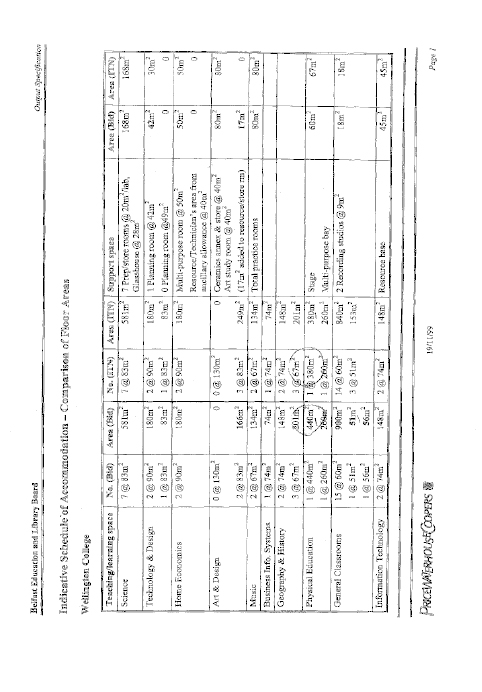

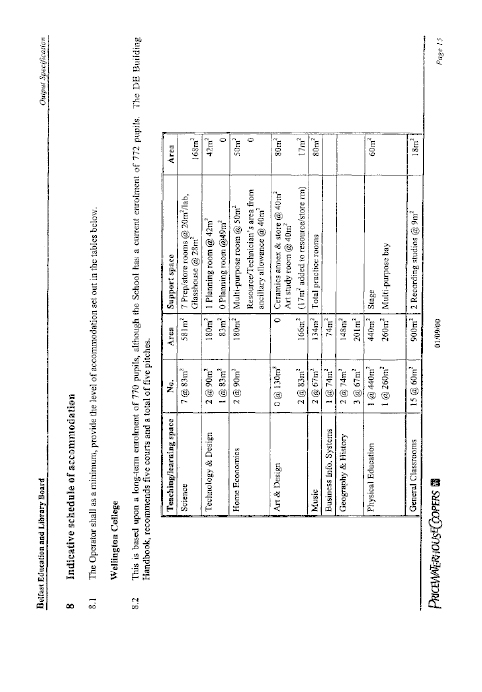

40. The Committee is disappointed that the Department’s Handbook has not been revised since 2003 and that recommendations contained in the NIAO report, “Building Schools for the Future”, have not yet been incorporated. The need to revise the Handbook is also clear from the facilities at Wellington and the views put forward by the College’s Governors. While the building was described by the Board’s Accounting Officer to the Committee as fit for purpose, in compliance with the Handbook and one of which the Board is proud, numerous design faults have been identified e.g. the corridors are too small, some rooms have heating problems, the IT rooms have no air conditioning to cool down the heated equipment, the Library is poorly located, the Sixth Form Centre is inadequate, and pitch boundaries are close to the school boundaries which limits wider community use.

41. From the evidence presented there must be a concern that, in the Wellington and Balmoral projects, the developer was more interested in securing the maximum amount of land for development. All the negotiations centred around the value of the land and what more could be squeezed out from the sites.

42. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Department has accepted that it can learn from this site and that, in hindsight, there may have been better ways of carrying out such a project. The Committee acknowledges that school facilities should be seen as a public asset that the school uses extensively, but that the community also gets the maximum use from. However the Committee is concerned that the Department has still to complete post project evaluations, five years after the schools were opened.

Recommendation 13

43. The Committee was critical that post project evaluations are not always carried out despite departmental guidelines. The Committee recommends that post project evaluations are always carried out and finalised as a matter of urgency.

Recommendation 14

44. The Department of Education should undertake a fundamental review of the current Building Handbooks to ensure they reflect the lessons learned from the post project evaluations and the findings of the NIAO report. The Committee also recommends that the revision of these Handbooks should involve the engagement of key stakeholders including principals, senior teachers and governors.

Recommendation 15

45. The Committee is dismayed by the closure of Balmoral High School only six years after it opened in 2002. It is evident that the Department faces a major challenge in managing school provision in the context of reducing enrolments across Northern Ireland. However, it is vital that finding a solution to this problem remains high on the Department’s priorities and that the lessons from the Balmoral experience are learned.

46. The Committee is alarmed at the Board’s assertion that the £860,000 in the Surplus Land Proceeds Account is not public money. Representing, as it did, the balance between the agreed value of the Wellington/Balmoral surplus lands and construction costs, it was due to and payable to the Board. However, the Board took a decision that, rather than receive the full amount upfront, it would allow the operator to retain it and offset it against the unitary payment over the 25 years of the contract. This was an extraordinary arrangement which smacks of payment in advance of need and seems to have been very poor value for money for the public purse. The Committee notes that action was only taken to put the necessary governance arrangements in place once preliminary enquiries were made by the NIAO. The Committee also notes that, on the basis of the interest currently being earned, the operator more than covers the annual offset against the unitary payment. Indeed it is not inconceivable that the operator will, at the end of 25 years, walk away with the £860,000.

Recommendation 16

47. The Committee recommends that such unnecessarily complex arrangements are avoided in future. More generally, when governance arrangements are agreed, they should be properly applied.

Minutes of Proceedings

of the Committee Relating

to the Report

Thursday, 4 October 2007

Lecture Theatre, Wellington College

Present: Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

In Attendance: Mrs Cathie White (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Gillian Lewis (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Nicola Shephard (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Patsy McGlone

The meeting opened at 2.00pm in public session.

2.01pm Mr McLaughlin joined the meeting.

3. Evidence on the NIAO Report ‘Transfer of Surplus Land in the PFI Education Pathfinder Projects’

The Committee took oral evidence on the NIAO report ‘Transfer of Surplus Land in the PFI Education Pathfinder Projects’ from Mr Will Haire, Accounting Officer, Department of Education (DE), Mr Eugene Rooney, Assistant Secretary, Development and Infrastructure Division, DE, Mr David Cargo, Chief Executive, Belfast Education and Library Board, Mr Stephen Halliday, Senior Valuer, Land and Property Services, Department of Finance and Personnel and Mr Tom Redmond, Head of Further Education Estates, Department of Employment and Learning.

Ms Purvis declared an interest as her two sons attend Wellington College.

The witnesses answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

The Committee requested that the witnesses should provide additional information on issues raised by members during the evidence session to the Clerk.

4.24pm The evidence session finished and the witnesses left the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday, 22 November 2007

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr Trevor Lunn

In Attendance: Mrs Cathie White (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Gillian Lewis (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Nicola Shephard (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Patsy McGlone

The meeting opened at 2.05pm in public session.

2.10pm Ms Purvis joined the meeting.

2.14pm The meeting went into closed session.

8. Consideration of Draft Committee Report on Transfer of Surplus Land in the PFI Education Pathfinder Projects.

Members considered the draft report paragraph by paragraph. The witnesses attending were Mr Kieran Donnelly, Deputy C&AG, Mr Brandon McMaster, Director of Value for Money, Mr Sean Beattie, Audit Manager and Mr Joe Campbell, Audit Manager.

The Committee considered the main body of the report.

Paragraph 1 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 2-4 read and agreed.

Paragraph 5 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 6-7 read and agreed.

Paragraph 8 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 9 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 10-12 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 13-19 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 20 – 22 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 23-28 read and agreed.

Paragraph 29 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 30 read and agreed.

Paragraph 31 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 32-33 read and agreed.

Paragraph 34 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 35-36 read and agreed.

Paragraph 37 read, amended and agreed.

3.59pm Mr Lunn left the meeting.

Paragraph 38 read, amended and agreed.

4.00pm Mr Dallat left the meeting.

Paragraphs 39-40 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 41 – 44 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 45 read and agreed.

The Committee considered the Executive Summary of the report.

Paragraphs 1-4 read and agreed.

Paragraph 5 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 6-8 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 9-10 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 11-13 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 14-15 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 16-17 read and agreed.

Agreed: Members agreed to amend the headings in the report.

Agreed: Members ordered the report to be printed.

Agreed: Members agreed that the correspondence from Mr Will Haire, Accounting Officer, Department of Education, Mr John Wilkinson, Chief Executive, Land and Property Services, Dr Aideen McGinley, Accounting Officer, Department for Employment and Learning and Mrs Edith Shaw, Chair, Board of Governors, Wellington College would be included in the Committee’s report.

Agreed: Members agreed to embargo the report until 00.01am on Thursday 13 December 2007.

Agreed: Members agreed to launch the report at a press conference on Thursday 13 December at 10am.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

4 October 2007

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr John O’Dowd (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr David Hilditch

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

Also in attendance:

Mr John Dowdall CB |

Comptroller and Auditor General |

|

Mr David Thomson |

Treasury Officer of Accounts |

Witnesses:

Mr David Cargo |

Belfast Education and Library Board |

|

Mr Will Haire |

Department of Education |

|

Mr Stephen Halliday |

Land and |

|

Mr Tom Redmond |

Department for Employment and Learning |

1. The Chairperson (Mr O’Dowd): I ask all our guests and witnesses to please turn off their mobile phones. Do not turn them to silent, as they will still interfere with the recording equipment.

2. I wish to thank the board of governors and the principal, staff and pupils of Wellington College for allowing us to use their school as our venue today. This is the first time the Public Accounts Committee has come out into the community for an evidence session, and I am sure we have caused a lot of disruption to the school day, but they have facilitated us very well.

3. The Assembly agreed on Monday that Mr Mickey Brady would replace Willie Clarke on this Committee, and I should like to take this opportunity to welcome Mickey on board for his first Committee meeting today. He has confirmed that he has no interests to declare, and that will be written into the record.

4. As members are aware, we are here today to take evidence on the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report on transfer of surplus lands in the PFI education pathfinder projects. I welcome Mr Will Haire, accounting officer for the Department of Education. Mr Haire, will you introduce your colleagues?

5. Mr Will Haire (Department of Education): On my right is David Cargo, chief executive of the Belfast Education and Library Board. On his right is Tom Redmond, head of further education estates in the Department for Employment and Learning. On my immediate left is Eugene Rooney, who is head of the development and infrastructure division in the Department of Education, and beside him is Stephen Halliday, who is senior valuer in the central advisory unit of Land and Property Services.

6. The Chairperson: Can you just raise your voice slightly for the recording equipment?

7. Mr Haire: Sorry.

8. Ms Purvis: Can I declare an interest, Chairman?

9. The Chairperson: Certainly.

10. Ms Purvis: My two sons attend Wellington College.

11. The Chairperson: Are there any other declarations of interest? No?

12. Mr Haire, the procedure today is that I will ask a number of questions at the start, and then the members will ask questions. An evidence session usually lasts around two hours. If we need to go over that time we will, but I am conscious that we are guests of someone else today, so I would like to keep to as tight a timetable as possible.

13. At paragraph 12 in the executive summary of the Auditor General’s report it states that:

“The Department [of Education] considers that including receipts from sale of surplus land can complicate a proposed scheme and there is now a general presumption that it would not be part of a scheme unless there were clear merits in doing so.”

14. It may be an obvious question at this stage, but what led you to those conclusions?

15. Mr Haire: The example that we have here demonstrates the complexity of proving that value for money has been achieved when both unitary payments and a land deal are involved in the negotiations.

16. The Department welcomes the fact that the report’s conclusion reflects that complexity. Value for money was demonstrated by the outline and final business cases, which the Department of Finance and Personnel signed off. Overall, the Department has achieved value for money: four new schools, two new colleges and a regional training unit are now established. Wellington College, for example, is now flourishing and has good accommodation, whereas the previous accommodation was terrible.

17. The sale of the land demonstrates the complexity of doing this and drawing that into a deal. The Department had effective surplus land agreements (SLAs) in place to try to achieve a solution. The problem was that, under PFI, the land could not be auctioned. The report estimates the total shortfall in the transfer value for the four contracts at some £4·2 million below the market value. Through the surplus land agreements, £3·8 million was clawed back on the Wellington and Balmoral projects, and we also recouped some £400,000 worth of benefit in the quality of the accommodation that was provided.

18. However, the different elements involved demonstrate the complexity of the process, which is an important factor to consider. As with the former Valuation and Lands Agency, the ideal solution is to hold a public auction of the land. Separating it would provide greater clarity in this process. However, the Department had to act according to the policy that was set for it in the late 1990s. There was a major affordability gap and serious shortfalls in the school estate.

19. This was a classic example of an excellent school suffering from being housed in buildings that were constructed in 1945. The Department was able to find a solution for the land that gave it value for money. However, the project demonstrates the real challenges involved in proving that value for money has been achieved.

20. There are examples in the report. For example, my colleagues in the Department for Employment and Learning can separate the sale of land in that process, because of the incorporation of the college. The Ministry of Defence example also demonstrates that there are new ways in which one can do these things.

21. Due to the size of the school estate, I am not sure how often this will be relevant to education facilities; our land banks are relatively small for such processes. However, the report usefully brings out the sheer complexity of the process. The Department and the board worked through the problems, learnt a lot in the process and were able to ensure that public funds were used appropriately.

22. The Chairperson: So, despite the findings of the report, you still think that you achieved value for money?

23. Mr Haire: The business case set out the value-for-money requirement, and we met that. The surplus land agreements recouped some of the funds that we estimated that we would not have had because of the way in which we had to do the deal at that time.

24. The question is whether better value for money could be achieved and better deals struck. That must be looked at in the context of the report. The Department recognises that it has more to learn.

25. The Chairperson: As some of my colleagues may touch on the question of value for money, I will not labour the point now. However, I may return to it at the end of the meeting.

26. Mr Cargo, as the board’s accounting officer, you signed the Wellington/Balmoral agreement, and paragraph 2.19 of the report records that you sought additional assurances from “the Department and its financial consultants” before signing the contract. Why did you consider it necessary to get assurances from the Department? Are you satisfied that you got value for money?

27. Mr David Cargo (Belfast Education and Library Board): I also welcome you to Wellington College, on behalf of the Belfast Education and Library Board. It is a first for the Public Accounts Committee to meet in a Belfast school.

28. It may be useful, when answering your question, to set the matter in context. The permanent secretary has highlighted the fact that this was an innovative and novel scheme, and there was no template to follow. As accounting officer, I was keen to ensure, first of all, that we complied with the processes laid down in Treasury guidelines, and that we had access to the best advice that was available.

29. The governance arrangements were that we set up a project board that comprised all of the stakeholders — the Belfast Board; the Department of Education; the school’s board of governors — and a strategic oversight of that project board by the education and library board. I had in place the background of a robust governance arrangement. Within that, the board and I were clear that we needed the best of advice. In our team of advisers we had legal, financial and other appropriate advisers — from the private and public sectors — to ensure that we were given the best advice in any decisions that we took.

30. That led up to the point where we were about to sign the contract. Board members were concerned about a number of issues at that stage. We needed to check that what we were about to recommend was both compliant and in keeping with the best possible arrangements, especially as regards the surplus land agreement.

31. The board had access to commercial legal advice, through its educational solicitors. We focused on the surplus land agreement and ensured that its terms, which were the basis of the clawback arrangements that we were able, subsequently, to achieve, were as robust as possible. I also checked with the permanent secretary that, in putting the scheme forward for overall approval by the Department of Education and the Department of Finance and Personnel, we ensured that it was value for money. Those issues were, quite properly, of concern to board members in the oversight of their responsibility. We received a letter from the permanent secretary that reassured me, and ensured that what I was proposing — as the accounting officer — complied with Treasury guidelines. The board members were then content to move on with the scheme.

32. The Chairperson: Did the board vote for the scheme on the basis of your recommendation? A number of points were raised by the board members:

“was the value of the surplus land negotiated with the bidder reasonable? … the value for money of the project, as the public sector comparator was 2.3 per cent lower than the final bid.”

33. Are you satisfied that the letter from the Department satisfied the board’s concerns and that, therefore, you could make a recommendation to the board?

34. Mr Cargo: Yes. A group of senior board members — following a discussion about the project at the board — set up a subcommittee that included the chairperson and the deputy chairperson of the board, the chairperson of the audit committee, the chairperson of the finance committee, and me. In a sense, we quality-assured what had already been done by our advisers. Our advisers had given us a report advising us that this constituted mitigation of the key risks and value for money. Then, in an exchange of letters with the Department, we satisfied ourselves that the scheme did, as presented in the business case, give us value for money and that the clawback arrangements were as robust as the report has recognised.

35. The report recognises that, as regards the shortfall on the land — which it suggests was £3·4 million — the board achieved a clawback of £400,000 more than that at £3·8 million. In a sense, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. The board members are content that what we did at the time achieved value for money, and that the assiduousness with which we examined the surplus land agreement ensured that the board was protected.

36. The Chairman: At any stage of your discussions, was the school involved in the discussions about what we have ended up with here today?

37. Mr Cargo: Yes. The school was involved at two levels: the board of governors was represented on the project board, which was the key management vehicle for the progress of the project, and the school had input into the design discussions.

38. The Chairperson: Paragraph 3.1 of the report sets out the key recommendations for clawback — which was referred to earlier — in relation to CastleCourt shopping centre. Mr Haire, can you explain to the Committee how the arrangements for this pathfinder project took account of the CastleCourt recommendations?

39. Mr Haire: The task in relation to CastleCourt was to regain an urban development grant. A problem arose because of the timescale attached to that grant. The clawback arrangements for this pathfinder project were developed during negotiations. The recovery of the resources from the land — the added value; the increased income as the land value goes up — took place over a longer period in this process. The surplus land agreement had many different mechanisms to deal with the volatility of the market. Although we knew at the outset that the developer wished to develop parts of the land, there was the possibility that some of it could have been sold undeveloped, or that the project might move in different ways. The land agreement was detailed and robust, and was able to deal with the different factors.

40. On the question of super-profits, the key point to make is that the surplus land agreement was about ensuring that the board got the value of the land. As the report shows, the Department was not involved in the operational profits gained from the development of the houses per se. We had not put anything into the agreement other than the land itself. The process was about recovering the value of the land. When questions are asked about profits, it is important to recognise that this exercise was about land values. It is somewhat different from what was being looked at in CastleCourt. The Department argues that our surplus land agreement gave a reasonable return. It gave us £400,000 more than if we had gone to auction at the time of the original transfer of the land. That is something that we could not do, because we were subject to PFI rules, but we had a mechanism that gave us a greater return.

41. The other important point that I want to make, and which is noted in the report, is that we did not have to decant the school. We were able to build the school on the land, which was important for continuity at the school and meant that the children were not disrupted. There have been instances in further education colleges in which up to £2 million has been spent decanting students. We did not have to do that in this instance.

42. I hope that I have been able to give the Committee some useful background information on the project. I will be happy to provide more details of the surplus land agreement. My colleague Stephen Halliday can go into more detail if the Committee would like to make comparisons.

43. The Chairperson: We may return to that towards the end of the meeting, because I am conscious that some of my colleagues want to examine that issue.

44. Mr Beggs: My first question is to Mr Haire. At paragraph 1.8 of the Audit Office report we are told that details of the surplus land on the Wellington site were circulated to some public-sector bodies, but not to the then Valuation and Lands Agency as is required. The Committee has been told that there was a requirement to advise the Valuation and Lands Agency of all surplus assets, but that did not happen in this case.

45. At paragraph 2.9 of the report we are told again that the Valuation and Lands Agency was not instructed to carry out an independent valuation of the Rosetta site. This was the second occasion on which it should have been involved. At paragraph 3.16 the report states that the Belfast Board appointed a commercial valuer in the dispute over the sale of the surplus land at Wellington and Balmoral. Why did the Department of Education and the Belfast Education and Library Board repeatedly fail to seek the advice and expertise of the Valuation and Lands Agency?

46. Mr Haire: As stated in paragraph 1.8 of the report, the Department of Education made a conscious decision that the land would be used in the educational process here, and that we would not seek to bring it into the broad issue of use for other public purposes. It was the understanding in these pathfinder projects that the land would be used for the education estate. There was some discussion with the Housing Executive, as it had land nearby. However, the Department made a conscious decision to not forward any details to the Valuation and Lands Agency.

47. As regards the Rosetta land issue, Mr Cargo and I both recognise that that was a mistake. There should have been discussions about the Rosetta land during the process. As the report explains, the board’s other consultants think that we got a reasonable return for the Rosetta land, but matters should not have been handled in that way. The Valuation and Lands Agency should have been involved, as it was closely involved in the structure. It was a particular time in the negotiations, and that connection failed to be made.

48. Finally, the external valuer, as I understand it, was an expert in negotiating with the private sector to make sure that we got the best return. This person was acknowledged as being an expert in that field. It was felt that this was the way to achieve the best returns. It can be seen that there were tough negotiations on the part of the Belfast Education and Library Board, as it got significant returns from what was originally offered.

49. Mr Cargo: The Belfast Education and Library Board was in contact with the Valuation and Lands Agency during the process in a general sense, and we followed its advice. However, following legal advice from our solicitors, we felt that the best way of ensuring optimum value from the clawback arrangements was to bring in a specialist commercial valuer to assist us with the negotiations. He negotiated on our behalf and struck the deal that resulted in £3·8 million coming back from the contractor. Using such a valuer did not imply in any way that we were diminishing the role of, or ignoring, the Valuation and Lands Agency. The board was merely trying to ensure that it had the most appropriate advice at all stages to ensure that it got the maximum and optimum rate of return.

50. Mr Beggs: It is questionable whether you got value for money, but my colleagues may pursue that issue. Do you accept that, at the very least, you incurred significant additional legal costs and professional fees as a result of that dispute?

51. Mr Haire: Can you clarify that?

52. Mr Beggs: When you started to go into the value of the clawback, you were in a dispute. You were advised that you had to bring in a negotiator to get a good deal, and there were costs incurred as a result of legal negotiations.

53. Mr Haire: There were additional costs, but that is the reality when you work on complex land deals. That is an inevitable part of the process. We have learnt a lot and gained experience, and the complexities of writing surplus land agreements are demonstrated in this process. It is likely that there will be arbitration in other areas in order to sort some of those issues out. No contract is going to be perfect. We recognise that that is an issue.

54. Mr Beggs: Paragraph 1.10 of the report sets out the Department for Employment and Learning’s proposed approach for dealing with surplus land. It appears that not all of the income would be offset against the private-sector borrowing in your examples. Why did you choose that method?

55. Mr Tom Redmond (Department for Employment and Learning): Retaining the receipts from disposals is an important factor in enhancing the affordability of the projects under construction. However, prior to the incorporation of the further education sector and to these two deals’ becoming part of the pathfinder projects, retaining the receipts was not the same as it is now.

56. Under the incorporation of colleges of further education, the Department has the power to enable a college to retain all the receipts for investment in the project. We have looked at the examples in the pathfinders and, because of our ability to retain all of the receipts, we thought it best to go to open-market disposal. As Mr Haire said earlier, it is much easier to demonstrate that value for money has been achieved through an open-market disposal. Our ability to retain the receipts for investment in the project, and thus enhance its affordability, allowed us to look at it in a different way.

57. Mr Beggs: I welcome the recognition that there are better methods of ensuring value for money, and I appreciate the use of that method by your Department.

58. I now ask a question of Mr Thomson. Paragraph 1.14 states that:

“since 1998, departments in GB have been allowed, within limitations, to retain receipts from the sale of fixed assets to support further investment, instead of returning them to the Treasury.”

59. What standing has the Lyons Report in Northern Ireland? What is the Department of Finance and Personnel’s line on retaining receipts?

60. Mr David Thomson (Treasury Officer of Accounts): The Department of Finance and Personnel will always want to encourage asset sales. However, there must be a balance between flexibility and incentives on the one hand and prioritisation on the other, especially when capital funding is tight.

61. In recent years, Ministers have taken different views on that. In the last few years, Ministers have said that Departments can keep 50% and return 50% to the Department of Finance and Personnel. Peter Robinson is thinking about that at the moment. In the proposals he will be taking to the Executive in the next few days on this year’s draft Budget, there will be recommendations on how to treat asset sales and targets for assets sales. Until the Executive discuss that, I cannot give any further commitment. It is an issue that the Executive will be considering.

62. Mr Beggs: Are you saying that, at present, Departments can keep 50%?

63. Mr Thomson: Under direct rule, that was the arrangement for sums under £10 million. Anything over £10 million came back to the centre anyway, so that it could be redirected to priority areas.

64. Mr Beggs: You have indicated that discussion on that is ongoing, but if something happens before that is settled — say, for example, today — what is the situation?

65. Mr Thomson: The Department of Finance and Personnel would look sympathetically at it. [Laughter.]

66. Mr Beggs: Have you ever looked sympathetically at anything?

67. Mr Brady: My question is for Mr Cargo. Paragraph 3.21 deals with the sale of land adjacent to the Balmoral site. Can you explain why the Belfast Board engaged consultants to demonstrate that the Water Service plot was not “key land”? How much did the consultants cost to engage? Was it not for the contractor to demonstrate that there were alternative access points to the site?

68. Mr Cargo: The issue arose following the building of the school and the development of the land, where a piece of land belonging to the Water Service — not to the Belfast Board — became an integral part of discussions about sightlines at the site. It happened when we were in the midst of negotiations about clawback. We consulted the Valuation and Lands Agency, and it was agreed that the optimum return to the public purse would be best served by the board’s concluding its negotiations, because an exchange of land was possible. The public-sector bodies arranged, through the Valuation and Lands Agency, to ensure that they achieved the optimum value. In that case, it was for the board to conclude its negotiations, which were well advanced.

69. Mr Brady: Paragraphs 3.29 to 3.31 discuss the definition of “extras”. Why was that term not properly defined in the contract? Is that another example of the use of ambiguous terms in an agreement, with the result that the public sector has lost out? Has the public sector settled for less than it should have?

70. Mr Cargo: In considering the land as an integral part of the negotiations, we were keen to ensure that we covered all eventualities in the surplus land agreement. At that time, the advice from the board’s solicitors was that a general clause existed that would cover the eventualities of “extras”. At that stage, it was difficult to second guess what type of homes — if any — would be built on the land if it were to be developed. Part of the problem was that the private sector had not obtained planning permission; therefore, the risks involved with obtaining planning permission rested with it.

71. During the detailed negotiations it transpired that there was an issue with “extras”. That concerned matters such as bathrooms in the houses. Again, during the negotiations, given the point at which the deal would be done, our advice was not to progress the “extras” to the nth degree because sliding scales were to operate in the overage, and so, ultimately, we could get a pyrrhic victory: we could fight the “extras” to the nth degree but end up getting less money. At that stage a commercial decision was taken not to fight the issue. However, I accept that, with hindsight, the term “extras” could have been better defined when the surplus land agreement and the arrangements were drafted. That is a fair comment.

72. Mr Craig: My first question is to Mr Cargo and is concerned with paragraph 2.9 of the report. I have listened carefully to some of the statements that were made earlier, Mr Cargo’s statement about using the specialist advisers for valuing the land. Even from a layman’s point of view, it seems that the report says that experts started negotiations with private developers. The trouble was that they started off on the basis that only one acre of land at Rosetta was being sold off. Do you not find it strange that nobody actually bothered to go out and measure that land? Paragraph 2.9 states that a 1·5 acre, rather than a one acre site, was being looked at. That means that the developer got a superb bargain.

73. I am being simplistic, but if a developer asked to buy my house, I would not take it for granted that its area was what he said that it was. The first thing that I would do would be to get someone to check the measurements.

74. Mr Cargo: The permanent secretary has already admitted that, with hindsight, the VLA should have been involved in the process of examining the Rosetta land. However, perhaps I could describe the scene at that time. I think that it is paragraph 12 of the report’s executive summary that acknowledges that that situation was part of very complex and fast-moving negotiations. There was some criticism of the length of time that the process was taking. Therefore, the board was always balancing speed and closure with prudence and ensuring that at all times there was a robust process in securing value for money.

75. The developer identified the Rosetta site late on in the process as a piece of land that he would want to be included in the negotiations. At a particular point in time when one looks with hindsight, there is a document that says that that piece of land was an acre.

76. A hockey pitch was also associated with the original piece of land. The amount of land varied during the negotiations. I have already accepted that we should have got the VLA to value the land. However, the report also acknowledges that, due to those negotiations, the board received £1·44 million for that 1·5 acres, which was valued at £1·32 million, because, in return for putting that land in the deal, we secured additional facilities, such as floodlit synthetic pitches, which, at that time were not included in any school building handbook. To the best of my knowledge, they were among the first such provisions in schools in Northern Ireland.

77. The outcome for the school and the young people in the area was that we secured much better facilities than would normally have been available. Those facilities were of the value of £1·44 million, which was better than the Audit Office’s estimated £1·32 million. However, I accept that the board should have gone back to the VLA. Sometimes in the heat of discussions and negotiations, especially those on the final details that close the deal, such things get overlooked.

78. Mr Haire: As the Department’s accounting officer, I should point out that we recognise that the process was not carried out in the right way. It was done in that way to ensure that we got what we described as:

“reasonable value for money within the overall bid”,

as quoted in paragraph 2.8 of the Audit Office report.

79. It goes back to the learning process. It is necessary to have a strategy for the marketing and sale of land, which must be worked through; otherwise, people get caught up in complex negotiations in the final stages of the deal. Therefore, a clear strategy is required. The Ministry of Defence adopted such a strategy, which is described on page 20 of the report, and another example is that which was used by my colleagues in the Department for Employment and Learning (DEL). Given that further education colleges can retain receipts, DEL can use different modes of procurement than the Department of Education can. Therefore, we recognise a lesson that must be learnt.

80. Mr Craig: I fully accept that there are lessons to be learnt; I am sure that the Committee also recognises that.

81. I accept what Mr Cargo said about relying heavily on the consultants and the experts. Is there any possibility of getting clawback from the consultants over the price of the land, because, as experts, they did not take value into account either?