Session 2009/2010

First Report

Public Accounts Committee

Report on the Investigation

of Suspected Contract Fraud

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE

RELATING TO THE REPORT AND THE MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

Ordered by The Public Accounts Committee to be printed 2 July 2009.

Report: 01/09/10 Public Accounts Committee

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts and reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 51 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Paul Maskey*** (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns** Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr Jonathan Craig Mr George Robinson****

Mr John Dallat Mr Jim Shannon*****

Mr Trevor Lunn Mr Jim Wells*

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke on 1 October 2007

* Mr Ian McCrea replaced Mr Mickey Brady on 21 January 2008

* Mr Jim Wells replaced Mr Ian McCrea on 26 May 2008

** Mr Thomas Burns replaced Mr Patsy McGlone on 4 March 2008

***Mr Paul Maskey replaced Mr John O’Dowd on 20 May 2008

****Mr George Robinson replaced Mr Simon Hamilton on 15 September 2008

*****Mr Jim Shannon replaced Mr David Hilditch on 15 September 2008

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report

Report

Improving Maintenance Procurement

The Investigation of Contract Fraud

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2:

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3:

Correspondence of 28 April 2009 from Mr Howard Ingram.

Chairperson’s letter of 26 May 2009 to Mr Howard Ingram.

Chairperson’s letter of 29 May 2009 to Mr Paul Sweeney,Accounting Officer, Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

Chairperson’s Letter of 29 May 2009 to Mr Will Haire Accounting Officer, Department of Education.

Correspondence of 12 June 2009 from Mr Will Haire, Accounting Officer, Department of Education.

Correspondence of 23 June 2009 from Mr Howard Ingram.

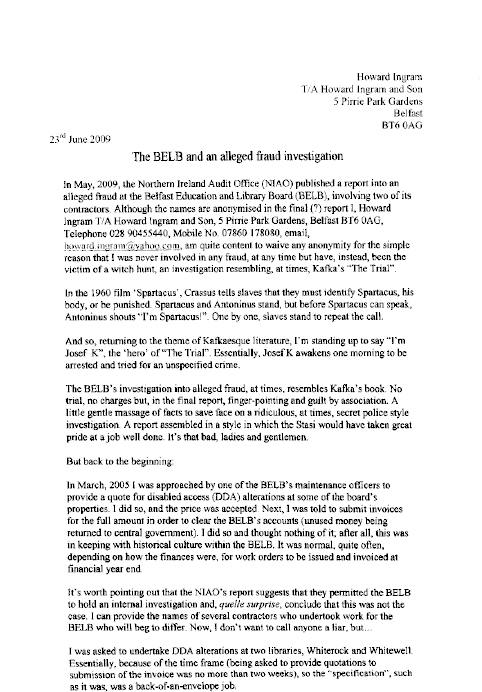

Appendix 4:

List of Witnesses

List of Abbreviations used in the Report

BELB Belfast Education and Library Board

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

COPE(s) Centre(s) of Procurement Expertise

DCAL Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

The Department Department of Education

Boards Education and Library Boards

ESA Education and Skills Authority

CORGI Council for Registered Gas Installers

OFT Office of Fair Trading

PAC Public Accounts Committee

Executive Summary

Overall Conclusions

1. The Committee considered the investigation of suspected fraud within the Property Services Unit of the Belfast Education and Library Board (BELB). This is one of the most worrying cases the Committee examined in terms of the failure of the public body to recognise the extent to which it was vulnerable to fraud and its slowness to respond as evidence of malpractice accumulated over the years. However, the Committee believes that this is not unique to BELB and there is a challenge for management throughout the public sector, wherever there is substantial expenditure on maintenance contracts, to ensure that robust procurement procedures safeguard public funds.

2. Very large sums of money are spent by public bodies on work by maintenance contractors. The Committee is aware of a £200 million backlog in maintenance work in schools which has resulted in significant deficiencies in the schools’ estate. It is vital that the limited budgets available to remedy these deficiencies are spent for the benefit of children, not contractors. In the current economic circumstances, all public officials must ensure that maintenance procurement is carried out on the basis of fair competition and that it delivers value for money.

3. The annual procurement spend by Northern Ireland Government is £2.2 billion. Even if only a small proportion of this spend is fraudulent very significant sums of public money are potentially lost. It is therefore crucial that the lessons learned in this report are applied throughout the public sector.

Improving Maintenance Procurement

4. The Committee notes that there was extensive evidence of a long-standing culture within BELB’s Property Services Unit that favoured certain contractors and had no regard for proper procurement procedures. When management recognises that it has a deep rooted cultural problem it is not sufficient to issue directives from on high, however comprehensively these are worded. The requirement is to drive a programme of structured cultural change in the area concerned.

5. The Committee notes a wide range of examples of alarmingly poor value for money in maintenance procurement in BELB. The Committee recognises that partnerships with private sector contractors and suppliers are essential for the delivery of public services and, properly administered, offer substantial efficiency gains. However, the interface between public bodies and their contractors needs to be handled professionally with proper regard for good procurement practice. In particular, ensuring that there is genuine competition between contractors, and that contracts are fairly awarded, is essential in achieving value for money. Those responsible for purchasing functions need to be alert to, and to check for, evidence of collusion between groups of bidders or between bidders and officials who are in a position to influence the placing of orders. It is also important that any concerns about suspected impropriety are investigated thoroughly and promptly.

6. The Committee finds it disturbing that management’s attention had been brought to weaknesses in the controls operating in BELB’s Property Services Unit by Internal Audit in a series of reports between 1997 and 2002, but no effective action was taken.

7. One BELB maintenance officer was involved in the award of £64,000 worth of maintenance work to his uncle’s firm. The Committee was told that this relationship was known both to the employee’s supervisor and to senior management, including the Chief Executive. The Committee considers that the BELB’s own instructions on dealing with conflicts of interest, issued in 2001, sent exactly the right message to staff on how to handle them. However, the Committee found it most disappointing that, in practice, these instructions were ignored and that this happened with the knowledge of senior management.

8. Another maintenance officer accepted a four-day visit to Italy arranged by a Northern Ireland supplier. The Chief Executive told us that his concern was that “the trip could be perceived as a junket". It is clear to the Committee that this is something of an understatement - of course this was a junket. It is extremely disappointing that public servants accepted generous hospitality from a third party who might well have expected to gain from future Board contracts.

9. The Committee is very concerned to read the Counter Fraud Unit’s conclusion that maintenance supervisors “appear to have abdicated any role in verifying invoices approved by their maintenance officers". Supervisory checks are a key control in this area and it is for management to ensure this control is operating effectively. The Committee notes that none of the supervisors’ line managers were subject to disciplinary action.

10. In August 2005, BELB identified that it had paid £80,000 for disability access work in Whitewell and Oldpark libraries which had never been started. When BELB reviewed work undertaken in other libraries it found that £110,000 had also been paid for work in 14 other libraries which was either not carried out or was not carried out to the required standard. The Committee is very disturbed by the photographs contained in the C&AG’s report. The work was so poor it had created a health and safety hazard and may well have damaged the structure of the building.

11. Every householder knows that, in commissioning maintenance work on buildings, they need to be alert to the dangers of unscruprulous contractors. While any contractor who secures a public sector tender should have been subject to careful quality checks, these are never a substitute for careful supervision of work done over the period of the contract and, most importantly, confirmation that work has been satisfactorily completed prior to payment. In the libraries case, the fact that very large amounts of money were paid out to contractors, months in advance of any work starting, underlines for the Committee that the culture in BELB was woefully deficient in safeguarding the taxpayer’s interest. The Committee is not surprised that there were strong suspicions of fraud in this case, even though extensive investigations were unable to establish evidence which would support criminal prosecutions.

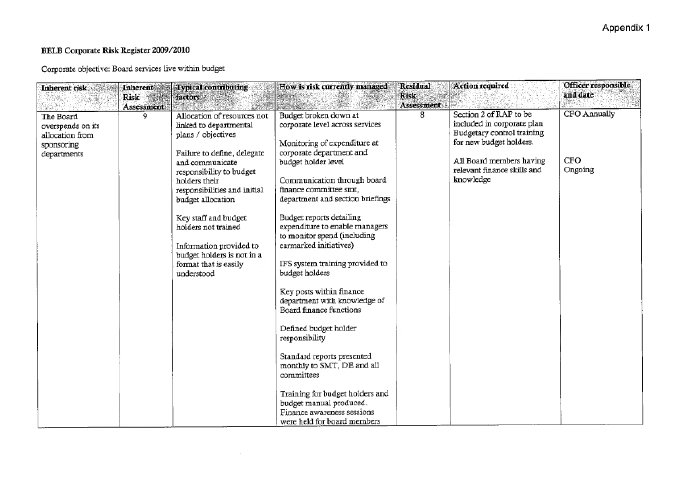

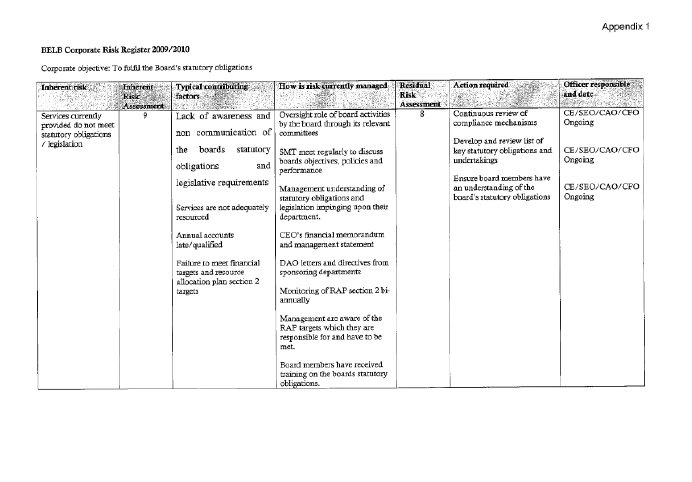

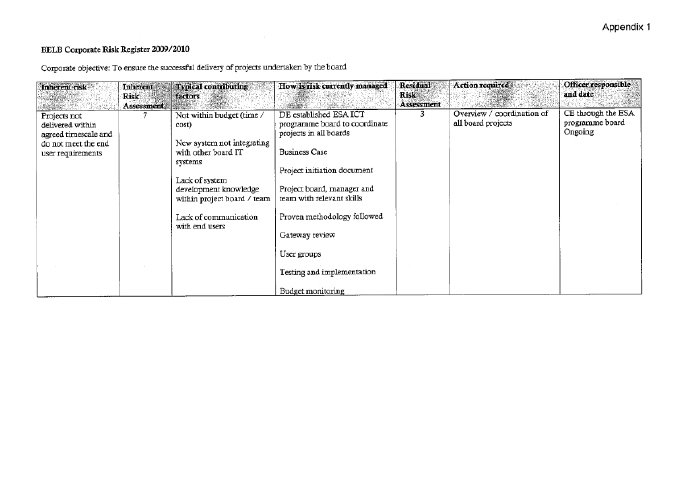

12. The Committee is shocked to discover the absence of normal procurement procedures in BELB given that it has been an accredited Centre of Procurement Expertise (COPE) since 2002. The Committee considers that the public would have drawn confidence from the award of COPE status and it is vital that the assessment of this status is independent and rigorous. COPEs which demonstrate persistent poor practice should have their status removed, if the concept of a ‘Centre of Procurement Expertise’ is to mean anything.

13. The Committee notes with concern the comments from Central Procurement Directorate of the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) that “it may be inappropriate for Centres of Procurement Expertise to share specific experiences of poor performance." The Committee disagrees strongly with this view. The public sector must put itself in a position to act as an intelligent purchaser and safeguard public funds by sharing its experience of very poorly performing contractors and take this information into account when awarding future public sector contracts.

The Investigation of Contract Fraud

14. The Department of Education (the Department) confirmed that BELB received a wide range of anti-fraud and procurement guidance from DFP and it simply was not followed in the cases the Committee examined. BELB had developed an anti-fraud policy and fraud response plan in 2000, but the policy, particularly in relation to line managers’ responsibilities, was not fully implemented.

15. This is not the first time that the Committee has emphasised the important role that whistleblowers have in the identification of potentially fraudulent activity. The Committee is disturbed to find that BELB did not effectively handle the investigations of two earlier anonymous letters, which had raised concerns of corruption and bid rigging. The schools’ maintenance case study strongly underlines the importance of investigating any concerns promptly and professionally. The Committee notes that the leads provided by the whistleblower in this case did not ultimately produce the level of evidence needed to pursue prosecutions. In the Committee’s view, the failure at the outset to have a properly resourced investigation may well have contributed to the inability to bring criminal or civil charges in this case.

16. The Committee recognises that, generally, the interventions of the Department were well directed at strengthening the investigation process and trying to ensure that it was as effective as possible.

17. Three officers in the schools case study faced disciplinary charges. The Department’s expert in disciplinary matters concluded that the relationship of two of these officers with a contractor “represented gross misconduct". The Committee is concerned that the Disciplinary Panel downgraded the offences from gross misconduct to misconduct. The two officers received a formal written warning. In the libraries case, another officer received a final written warning for serious misconduct. In all cases these warnings were removed from their records after one year. In the Committee’s view, the public perception of these disciplinary measures, when they are removed after a relatively short time, is that they are too light.

18. In the libraries case the officer managing the project was suspended on full pay in 2005 and his employment terminated in 2007 on ill health grounds and the disciplinary hearing against him was wound up. This is a matter of concern, as this is not the first case the Committee has come across where disciplinary action has been stopped on medical grounds.

19. In both case studies the Committee found that the failure to implement proper procedures and the absence of documentation had undermined the prospect of criminal charges being brought. The Committee recognises that this makes redress much more difficult. Nevertheless, it is important that every possible action is taken to recover sums overpaid or paid for work not done.

20. The Committee is pleased that the Department has sought to learn lessons from its performance in investigating the whistleblower’s allegations. The witnesses recognised that the investigation took too long to reach a conclusion and should have been taken forward more rapidly. The Committee agrees with this assessment. It should not have been necessary to undertake more than one investigation into the schools maintenance case study. A properly resourced and planned investigation should have been sufficient to deal with the matter authoritatively.

Summary of Recommendations

The Improvement of Maintenance Procurement

Recommendation 1

1. The Department of Education has required each Education and Library Board’s (Board’s) Internal Audit Unit to review procurement in the light of this case. The Committee recommends that all public bodies with annual maintenance procurement of more than £1 million should conduct a similar review against the lessons emerging from this report. The Committee would ask the Audit Office to confirm that these reviews have been completed as part of its audit of next year’s accounts and to report back on any omissions. Others with lesser budgets should consider appropriate lessons for themselves. (see paragraph 8)

Recommendation 2

2. Where there is evidence of longstanding poor practice which puts public funds at risk, the Committee recommends that the public bodies are alert to the need to address the underlying culture in the units concerned as well as to improve procedures. In the Committee’s view, the keys to this are leadership to drive up standards, good supervisory management to ensure that rules are applied and appropriate disciplinary action when failures occur. (see paragraph 10)

Recommendation 3

3. The Committee recommends that when any public body receives a report from an Internal Audit unit which indicates that key controls are inadequate, and there is repeated failure to apply the procedures which are safeguarding against fraud and impropriety, management must set itself the task of tackling this with the highest priority within a short, targeted timeframe. In addition, Internal Audit should be asked to give assurances that this has been completed. (see paragraph 12)

Recommendation 4

4. The Committee recommends that in areas of expenditure such as maintenance contracts, which have been recognised as vulnerable to abuse, management must ensure that staff are alert to the need to challenge any instances of poor value for money and are encouraged and empowered to do so. (see paragraph 16)

Recommendation 5

5. The Committee considers that the 2001 instructions on dealing with conflicts of interest sent exactly the right message to staff; it is therefore extremely disappointing to learn that, in practice, these instructions were ignored and that this happened with the knowledge of senior management. The Committee insists that not only must there be clear instructions about the handling of conflicts of interest but, senior management must enforce zero tolerance of any perception of impropriety. (see paragraph 20)

Recommendation 6

6. The Committee recommends that there should be regular awareness training on the standards in public life for all staff involved in procurement, and guidance on gifts and hospitality should be re-issued annually to procurement staff. (see paragraph 23)

Recommendation 7

7. The Committee recommends that when engaging contractors who are required to have a specialist qualification/registration, particularly where there is a health and safety element to the work, this requirement must be written into the terms of the contract and documentary evidence inspected before the contract is signed. (see paragraph 25)

Recommendation 8

8. The Committee recommends that public bodies managing maintenance procurement must ensure that there is adequate supervision of staff who let, manage and monitor maintenance contracts. Maintenance officers must carryout regular inspections of contractors’ work, involving, if appropriate, specialist staff, such as surveyors. Supervisors and managers should carryout random checks of work against the job specification. There should be no job, no matter how small in value, which could not be selected for checking by a supervisor. All work inspected and the results of all inspections should be recorded. Certification of invoices for payment should be based on proper validation that the work was carried out. It is extremely disappointing that the Committee finds it necessary to spell out these elementary points of good practice. (see paragraph 28)

Recommendation 9

9. The Committee is seriously concerned that BELB failed to obtain Building Control approval and may have put at risk the safety of the public and the preservation of public property. In the Committee’s opinion, it should not be left to the discretion of individual maintenance officers when, or if, Building Control approval is obtained. The Committee recommends that DFP ascertain whether this is a wider problem and, if necessary, require that all public bodies to review their systems and procedures for obtaining Building Control approval. (see paragraph 32)

Recommendation 10

10. The Committee would emphasise that the standard of proof required to act against poor contractors is not equivalent to that required in a criminal case. The public sector must be able to share its experience of poorly performing contractors and to take this into account when awarding future public sector contracts. If the guidance on this is not clear, or if there are perceived legal impediments, the Committee would like a report back from DFP on what needs to be done to strengthen the public bodies’ ability to take account of the track record of contractors working across the public sector. (see paragraph 34)

Recommendation 11

11. A key step in ensuring value for money in maintenance contracts is the appointment of competent contractors in the first place. The Committee recommends that public bodies should ensure that a wide range of firms are attracted to compete, and that tenders/quotes for maintenance work must be properly evaluated by trained and competent staff with an appropriate emphasis on quality as well as price. (see paragraph 35)

Recommendation 12

12. The Committee recommends that public bodies engaged in maintenance procurement ensure that locally based staff are used, where appropriate, to assist in assessing the quality of maintenance work undertaken on their premises. (see paragraph 37)

Recommendation 13

13. The Committee insists that public bodies must not set aside key safeguards for ensuring value for money simply to make sure that funding is spent before the year end. (see paragraph 39)

Recommendation 14

14. The circumstances of this case made the Committee question what one would have to be guilty of to lose accreditation as a Centre of Procurement Expertise (COPE). The Committee recommends that COPEs which demonstrate persistent poor practice should have their status removed, if the concept of a “Centre of Procurement Expertise" is to mean anything. (see paragraph 44)

Recommendation 15

15. The Committee notes the COPE status of the Education and Skills Authority (ESA) will be reviewed within a year of its establishment. Given the scale of the historic problems within BELB, the Committee recommends that this assessment of COPE status must be rigorous and independent. (see paragraph 46)

Recommendation 16

16. The Committee recommends that ESA draws up an Action Plan for maintenance procurement, drawing on the recommendations of this report. (see paragraph 48)

The Investigation of Contract Fraud

Recommendation 17

17. 17. The Committee recommends that there must be absolute clarity in every area of public purchasing that there are no circumstances where it is acceptable to solicit or provide invoices stating that work has been done where it has not. (see paragraph 51)

Recommendation 18

18. It is pointless issuing anti-fraud guidance unless it is properly implemented. The Committee recommends that all public bodies should periodically revisit their anti-fraud guidance, including the safeguards and checks on bid-rigging, and ensure that these are being implemented effectively. (see paragraph 58)

Recommendation 19

19. The whistleblower’s role was central to triggering the investigation in this case. The Committee recommends that Audit Committees be informed of any whistleblowing cases and how they are handled, and that DFP take the opportunity to draw attention to this case in its next Annual Fraud Return, and that any future training on fraud awareness pays particular attention to the value and effective use of whistleblower information. (see paragraph 63)

Recommendation 20

20. The Committee recommends that whenever a sponsored body is investigating allegations of serious suspected fraud, the sponsoring department should ensure that its own expertise is available and whatever other expertise is required, to assist in the investigation, and the department’s Accounting Officer must, of course, be satisfied that the process is thorough and professional. (see paragraph 65)

Recommendation 21

21. The Committee has made it clear that it expects public bodies to operate effective whistleblowing policies; proactively encourage and promote those policies; and rigorously investigate all whistleblowing concerns. The Committee recommends that DFP should draw attention to the Department’s handling of this whistleblower as a model for any future cases. (see paragraph 68)

Recommendation 22

22. The Committee is very concerned that it has to repeat a previous recommendation that all members of an investigation team, including its leader, should be totally independent of the management of the business unit where the fraud or suspected fraud occurs. (see paragraph 71)

Recommendation 23

23. BELB should have initiated independent investigations of these letters which could have dealt with the matter properly. The Committee recommends that where a whistleblower makes serious allegations of fraud, management must respond by conducting an appropriate investigation. (see paragraph 74)

Recommendation 24

24. Fraud Risk Registers are living documents that provide snapshots over time of an organisation’s management of fraud risk in the face of changing circumstances. The starting point for the creation of the Risk Register is a proper fraud risk assessment. The Committee recommends that every public body with maintenance expenditure in excess of £1 million per annum should ensure that the risk of fraud in this area is specifically dealt with in its risk assessment, and the outcome reflected in its Risk Register. (see paragraph 78)

Recommendation 25

25. The Committee recommends that any anomalies in disciplinary procedures in the public sector are reviewed and addressed appropriately. (see paragraph 81)

Recommendation 26

26. The Committee recommends that where there is strong evidence of wilful neglect of duty by staff, management should be prepared to place considerable weight on facts of this nature, as evidence of possible gross misconduct. To do otherwise does not send the right signal to staff. In addition, DFP should consider whether sponsoring departments should be represented on disciplinary panels, where suspected fraud is under consideration in their arm’s-length bodies, to add the weight of their greater experience in handling such serious issues. (see paragraph 83)

Recommendation 27

27. The Committee recommends that DFP should review a sample of cases from across the public sector of early retirements for reasons of ill-health or inefficiency where disciplinary proceedings are outstanding. The purpose of the review should be to identify whether there is scope to speed up disciplinary proceedings or to improve the handling of such cases, including early notification to Occupation Health Service that a disciplinary/grievance process is under way, and analysis of the implications for line management. The Committee would like to know the outcome of this review. (see paragraph 86)

Recommendation 28

28. This Committee has already recommended that whistleblowers should be encouraged and supported to engender a healthy anti-fraud culture. It is also important however, that public sector leaders ensure that staff whose actions lead to the identification of potential fraud and impropriety are explicitly commended, and the Committee recommends that their efforts are recognised appropriately. (see paragraph 88)

Recommendation 29

29. The Committee recommends that BELB should consider pursuing legal action in respect of other library works not done, or not carried out to the required standard. The Committee would like to be kept informed of progress. (see paragraph 91)

Recommendation 30

30. The Committee welcomes the transparency of the Department’s new fraud reporting procedures and recommends that there should be close liaison with DFP’s Fraud Forum to promote the good practice arising from the Department’s Review and to circulate the Review’s recommendations widely across the public sector. (see paragraph 96)

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee (the Committee) met on 28 May 2009 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report on “The Investigation of Suspected Contract Fraud" (NIA 103/08-09). The witnesses were:

- Mr Will Haire, Accounting Officer, Department of Education (the Department);

- Mr Paul Sweeney, Accounting Officer, Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL);

- Mr David Cargo, Chief Executive, Belfast Education and Library Board (BELB);

- Mr John McGrath, Deputy Secretary Resources and Accountability, Department of Education;

- Mr John Dowdall CB, Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG); and

- Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP).

The Committee wrote to Mr Haire and Mr Sweeney on 29 May 2008 with further queries, and they replied on 12 June 2009.

2. In August 2003, a whistleblower alleged that a price-fixing cartel was operating against the Belfast Education and Library Board (BELB) and that the cartel colluded with a number of BELB maintenance officers in the award of schools maintenance work. The whistleblower also alleged that these officers accepted inducements to award maintenance work to favoured contractors. The resulting investigations uncovered significant failings in maintenance procurement including poor value for money, conflict of interest concerns and evidence of favouritism towards certain contractors. The investigations were overseen by the Department of Education (the Department).

3. In August 2005, BELB uncovered a suspected fraud at two of its library building works. Physical inspections showed that building work, for which the contractors had been paid £80,000, had not been started. BELB also discovered that work at its other libraries, for which it had paid £110,000, had not been done, or had not been completed to an acceptable standard. The work was funded by the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL) and was intended to bring libraries into compliance with the access requirements of the Disability Discrimination Act.

4. In taking evidence, the Committee focused on two key areas. These were:

- improving maintenance procurement; and

- the investigation of contract fraud.

Improving Maintenance Procurement

General Findings

5. Fraud is an insidious crime, and property maintenance within the public sector has long been regarded as carrying a high risk of fraud, corruption and other irregularity. Public bodies are expected to be alert to these risks, have formal procedures to deter attempted fraud and enforce detection and respond vigorously to any evidence of impropriety.

6. Against this background BELB’s handling of issues arising from whistleblowers’ allegations of price-fixing and collusion in schools maintenance expenditure, from 1998 onwards, is deeply disturbing. This is one of the most worrying cases the Committee has considered in terms of the failure of the public body to recognise the extent to which it was vulnerable to fraud and its slowness to respond as evidence of malpractice accumulated over the years. However, the Committee believes that this is not uniquely a problem in BELB and that there is a challenge for management throughout the public sector, wherever there is substantial expenditure on maintenance contracts, to ensure that robust procurement procedures safeguard public funds.

7. The Committee recognises that it was very helpful in terms of progressing the session that the witnesses readily acknowledged the serious shortcomings and the handling of maintenance contracts in this case. It is important that senior management and Accounting Officers take responsibility for long standing weaknesses on this scale but also, as in this case, apply their experience to assist the Committee to identify what can be done to reduce the incidence of such problems in future.

Recommendation 1

8. The Department has required each Education and Library Board’s (Board’s) Internal Audit Unit to review procurement in the light of this case. The Committee recommends that all public bodies with annual maintenance procurement of more than £1 million should conduct a similar review against the lessons emerging from this report. The Committee asks the Audit Office to confirm that these reviews have been completed as part of its audit of next year’s accounts and to report back on any omissions. Others with lesser budgets should consider appropriate lessons for themselves.

9. BELB had introduced revised maintenance procurement procedures in 1998, but this failed to address the culture within its Property Services Unit, and weaknesses continued for too long. The Committee notes that there was extensive evidence of a culture within the Property Services Unit that favoured certain contractors and had no regard for proper procurement procedures. The Committee listened carefully to the Chief Executive’s account of the actions he has taken in this area from 1998. The concern, however, is that seven years later these actions had still not resulted in the change in culture that was necessary to reduce the potential for fraud in contract maintenance work. The lesson from this is that, when management recognises that it has a deep rooted cultural problem, it is not sufficient to issue directives from on high however comprehensively these are worded. The requirement is to drive a programme of structured cultural change in the area concerned. The Committee recognise, of course, that as the Chief Executive explained, people will “sometimes let you down" and there is also a need, therefore, for appropriate disciplinary action where failures occur.

Recommendation 2

10. Where there is evidence of longstanding poor practice which puts public funds at risk, the Committee recommends that the public bodies are alert to the need to address the underlying culture in the units concerned, as well as to improve procedures. In the Committee’s view, the keys to this are leadership to drive up standards, good supervisory management to ensure that rules are applied and appropriate disciplinary action when failures occur.

Internal Audit raised concerns that a core group of contractors was awarded most maintenance work but no effective action was taken

11. BELB’s Internal Audit Unit produced a series of reports between 1997 and 2002 which found that a core group of contractors was allocated the majority of the work in certain areas of maintenance work. What is disturbing is the extent to which Internal Audit brought these weaknesses in control to management’s attention, only for no effective action to be taken. This calls into question whether Internal Audit within BELB was accorded sufficient status to ensure that important recommendations were implemented.

Recommendation 3

12. The Committee recommends that when any public body receives a report from an Internal Audit Unit which indicates that key controls are inadequate, and there is repeated failure to apply the procedures which are safeguarding against fraud and impropriety, management must set itself the task of tackling this with the highest priority within a short, targeted timeframe. In addition, Internal Audit should be asked to give assurances that this has been completed.

Maintenance procurement in BELB had insufficient regard for value for money

13. The procurement procedures used by BELB between 1998 and 2006 were unlikely ever to have delivered value for money. Contractors could charge their trade associations’ hourly rates, plus a mark-up of 85% to cover the contractors’ overheads and profit. The Chief Executive told the Committee that this practice was “generally accepted at that time". It is difficult to understand how such an inherently flawed system could have continued, without question, until 2006.

14. The Committee noted a wide range of examples of alarmingly poor value for money. In one instance a contractor charged eight hours each for a plumber and an assistant to plumb a washing machine at a total cost of £266. Moreover, most work was allocated to the firm that charged the highest rates, a contractor who charged 43% more than the hourly rate of the cheapest contractor, yet both had passed the quality assessment before their appointment. The Committee welcomes the Accounting Officer’s recognition that this was clearly not good practice. He reassured the Committee that processes have been changed to focus on value for money.

15. The Chief Executive explained that the appointment of a number of quantity surveyors had allowed a much greater focus on ensuring value for money. However, it seems to the Committee that overcharging by certain contractors was so blatant it should not have taken a quantity surveyor to spot it – any member of maintenance staff or finance staff coming across grossly inflated invoices should be capable of challenging them.

Recommendation 4

16. The Committee recommends that in areas of expenditure such as maintenance contracts, which have been recognised as vulnerable to abuse, management must ensure that staff are alert to the need to challenge any instances of poor value for money and are encouraged and empowered to do so.

There was evidence of favouritism towards certain contractors, and procedures to address conflicts of interest were ignored

17. BELB Internal Audit investigations arising from a whistleblower’s allegations in 2003 found that two contractors were consistently awarded the majority of jobs. The contractors were awarded 50% of response maintenance work and 73% of emergency work. A consultant employed by the Department to investigate aspects of the case concluded that two BELB officers had favoured one of these contractors. These officers were subsequently disciplined for misconduct, in part due to their failure to follow instructions to rotate contractors on an equitable basis. When the Committee pressed the Accounting Officer on whether there had been favouritism, he said that while it was a concern, nothing had been pinned down. He added that while he would like to know whether favouritism had happened, “the fact that our process was open and left the threat of poor value for money is as bad as something actually going wrong". The Committee welcomes these comments.

18. In a 17 month period between April 2002 and August 2003, a Maintenance Officer, referred to in the C&AG’s report as Officer D, was involved in the award of £64,000 worth of maintenance work to his uncle’s firm. The officer had declared the conflict of interest to BELB on his appointment. The Committee was told that this relationship was known both to the employee’s supervisor and to senior management including the Chief Executive himself. The Committee was also told that this conflict was managed, in that there was a clear segregation of duties; while Officer D did not allocate work or approve payments, he did however approve the works order.

19. However, when the Committee compares how this conflict was handled to the instructions issued by BELB to its staff in February 2001, the Board’s actions emerge in a very different light. The 2001 instructions, issued by the Chief Administrative Officer, are worth quoting in full:

“It has been observed that certain officers have family or other personal relationships with contractors who undertake works or supply contracts or services for the department. In these circumstances officers could be offering work to, or agreeing payment for work carried out by their relatives, friends or those with whom they have other types of connections. There is no suggestion of any illegal activity taking place but there is an understandable desire to have procedures that will stand scrutiny and preclude the possibility of any accusations being made.

Staff are not permitted to be involved in any way with the procurement of, direction of, or payment for, any works or supplies which involves the use of any persons, firm or company where there is a family or other connection. Such persons, firms or companies shall not be debarred in any way from undertaking work for, or from supplying goods or services to the Board, but members of staff concerned will not take any part in the procurement, direction or payment processes."

Recommendation 5

20. The Committee considers that the 2001 instructions on dealing with conflicts of interest sent exactly the right message to staff; it is therefore extremely disappointing to learn that, in practice, these instructions were ignored and that this happened with the knowledge and tacit agreement of senior management. The Committee demands that not only must there be clear instructions about the handling of conflicts of interest, but senior management must enforce zero tolerance of any perception of impropriety.

BELB Officers accepted junkets from contractors

21. A maintenance officer accepted a four-day visit to Italy arranged by a Northern Ireland supplier. The visit was ostensibly to see boilers being made, but it included an excursion to the Ferrari factory. The Chief Executive told the Committee that BELB has never used this company’s boilers. He added that his concern was that “the trip could be perceived as a junket". It is clear to the Committee that this is something of an understatement - of course this was a junket. It was not the only such occurrence – the Audit Office report stated that another maintenance officer attended two golf outings paid for by contractors. The Committee welcomes the fact that two BELB officers were disciplined in relation to the Italian trip - the officer who attended and his supervisor who approved his attendance. The officer who attended golf outings also received a verbal warning.

22. BELB had a gifts and hospitality register in place, as well as a Code of Conduct. It is extremely disappointing that, despite this, public servants accepted generous hospitality from a third party who might well have expected to gain from future BELB contracts. One of the Seven Principles of Public Life[1] is integrity:

“Holders of public office should not place themselves under any financial or other obligation to outside individuals or organisations that might influence them in the performance of their official duties."

Recommendation 6

23. The Committee recommends that there should be regular awareness training on the standards in public life for all staff involved in procurement, and guidance on gifts and hospitality should be re-issued annually to procurement staff.

BELB awarded gas installation work to unregistered contractors

24. The Committee notes that two contractors were awarded contracts involving gas installations although neither was CORGI[2] registered. One of the contractors was considered by the Department’s consultant to have been favoured by a maintenance officer, and another maintenance officer had a family connection to the second contractor. While BELB was later able to confirm that work was undertaken by registered sub-contractors, it should not have been awarded to a firm which was not itself accredited. This is a matter of significant concern. While it appears that no child was endangered, this seems to have been a matter of good luck rather than the result of the actions of BELB.

Recommendation 7

25. The Committee recommends that when engaging contractors who are required to have a specialist qualification/registration, particularly where there is a health and safety element to the work, this requirement must be written into the terms of the contract and documentary evidence inspected before the contract is signed.

BELB failed to ensure that maintenance staff were properly supervised

26. The DCAL Accounting Officer told the Committee that one of the core weaknesses in the case studies examined was supervisory negligence. The supervisor in the library case approved payments on the basis of trust alone and conducted no verification visits himself. The absence of supervisory checks not only leaves public bodies open to fraudulent action by staff and contractors, but it weakens any potential prosecution case if such abuse is identified.

27. The Committee is concerned to read the Counter Fraud Unit’s conclusion that maintenance supervisors “appear to have abdicated any role in verifying invoices approved by their maintenance officers". While supervisory checks are a key control in this area, it is for management to ensure this control is operating effectively. The Committee notes that none of the supervisors’ line managers were subject to disciplinary action. The Chief Executive explained that the necessary computerised management information system was not in place until 2003. This is not a convincing explanation for the lack of management oversight of the activities of its maintenance supervisors.

Recommendation 8

28. The Committee recommends that public bodies managing maintenance procurement must ensure that there is adequate supervision of staff who let, manage and monitor maintenance contracts. Maintenance officers must carry out regular inspections of contractors’ work, involving, if appropriate, specialist staff, such as surveyors. Supervisors and managers should carry out random checks of work against the job specification. There should be no job, no matter how small in value, which could not be selected for checking by a supervisor. All work inspected and the results of all inspections should be recorded. Certification of invoices for payment should be based on proper validation that the work was carried out. It is extremely disappointing that the Committee finds it necessary to spell out these elementary points of good practice.

The standard of workmanship by some contractors was appalling

29. On identifying that it had paid for work in two libraries which had not been completed, BELB reviewed the work undertaken in other libraries to comply with disability legislation, and found it had paid £110,000 for work in 14 libraries which was either not carried out, or was not carried out to the required standard. At Whiterock library for example, £15,920 had been spent on disability works; BELB subsequently valued the work completed at £4,700. The work at Whiterock library was of such poor quality that BELB had to pay another contractor £900 to bring it up to an acceptable standard.

30. The Committee is very disturbed by the photographs contained in the C&AG’s report showing the appalling standard of workmanship at Whiterock library. The work was so poor that it created a health and safety hazard and may well have damaged the structure of the building. The Committee welcomes the Chief Executive’s assurance that shoddy workmanship is “no longer acceptable" – but of course this should never have been in question.

Public bodies must ensure Building Control approval is obtained where necessary

31. The Committee is surprised that the Chief Executive could not say whether building work in BELB had Building Control approval. He later confirmed that this approval is required if alterations of a structural nature are made. The maintenance officer managing the library works should have applied for, and obtained, Building Control approval and it is quite clear from the Chief Executive’s response that he did not. The Committee notes that BELB is currently undertaking a review of disability access works in libraries and will apply for retrospective approval where necessary.

Recommendation 9

32. The Committee is seriously concerned that BELB failed to obtain Building Control approval and may have put at risk the safety of the public and the preservation of public property. In the Committee’s opinion, it should not be left to the discretion of individual maintenance officers when, or if, Building Control approval is obtained. The Committee recommends that DFP ascertain whether this is a wider problem and, if necessary, require that all public bodies review their systems and procedures for obtaining Building Control approval.

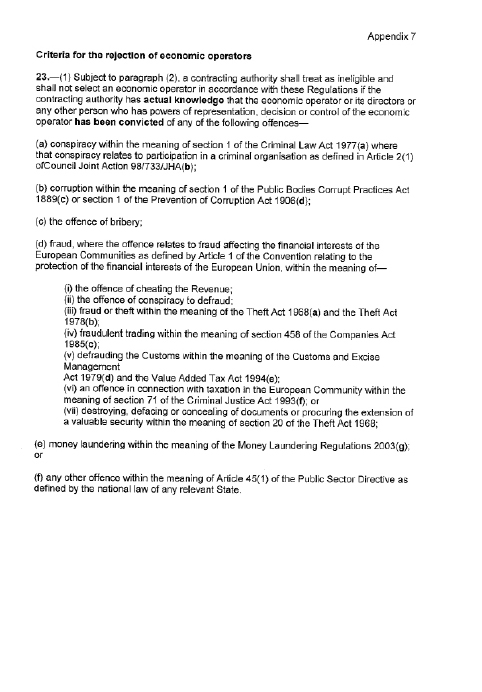

Public bodies must act to ensure poorly performing contractors should lose eligibility for future work

33. While the library case identified instances of alarming standards of workmanship by BELB contractors, the Committee notes that witnesses appeared uncertain about the scope to debar them from future work. The witnesses seemed to the Committee ill-prepared to deal with matters of procurement policy and procedures; this is perhaps indicative of the low priority afforded to such matters among senior administrators and the generally weak response to poor performance by contractors.

The Committee notes with concern the comments from Central Procurement Directorate of DFP that “it may…. be inappropriate for Centres of Procurement Expertise to share specific experiences of poor performance. Sharing of information of this type could be perceived as prejudicing contractors from winning future work without them having any opportunity to challenge the assessment that their performance was in fact poor, or make the COPEs aware that they have taken management action to correct the problem and that their performance has now improved". The Committee is astounded at this response. Where the public sector has experience of previous failings, public bodies should be able to use this to take decisions in the employment of contractors; without this information, they are likely to remain vulnerable to unscrupulous or incompetent contractors. The public sector must put itself in a position to act as an intelligent purchaser and safeguard public funds by using all available information.

Recommendation 10

34. The Committee would emphasise that the standard of proof required to act against poor contractors is not equivalent to that required in a criminal case. The Committee recommends that the public sector must be able to share its experience of poorly performing contractors and to take this into account when awarding future public sector contracts. If the guidance on this is not clear, or if there are perceived legal impediments, the Committee would like a report back from DFP on what needs to be done to strengthen public bodies’ ability to take account of the track record of contractors working across the public sector.

Recommendation 11

35. A key step in ensuring value for money in maintenance contracts is the appointment of competent contractors in the first place. The Committee recommends that public bodies should ensure that a wide range of firms are attracted to compete, and that tenders/quotes for maintenance work must be properly evaluated by trained and competent staff with an appropriate emphasis on quality as well as price.

Library staff failed to identify that work paid for had not been done

36. The Committee was disturbed to learn that although senior libraries management were monitoring the spend on Disability Discrimination Act work in libraries and getting updates from the project manager, they failed to identify that work had been paid for that had not been done. DCAL considers that, having delegated responsibility to the Education and Library Boards, it was entitled to place reliance on the operation of their processes and controls to ensure that work was satisfactorily completed. However, the DCAL Accounting Officer accepted that it was “remarkable that the staff in libraries played no role whatever". The Committee agrees with this assessment. DCAL has since required librarians to log contractors in and out of libraries so that there is at least a record of their attendance.

Recommendation 12

37. The Committee recommends that public bodies engaged in maintenance procurement ensure that locally based staff are used, where appropriate, to assist in assessing the quality of maintenance work undertaken on their premises.

Standing Orders were set aside to use up funding

38. The Committee was surprised to learn that, in January 2005, BELB’s General Purposes and Finance Committee approved an exception to Standing Orders so that disability work in certain libraries could go ahead without tender/quotation. The Chief Executive explained that work was allowed to proceed on that basis because funding arrived late in the financial year and BELB could not have spent the money “if it had gone through normal tendering procedures". The Committee does not accept the Chief Executive’s assertion that this “was the proper thing to do". The Committee could understand normal procedures being circumvented for urgent health and safety reasons – but to put value for money at risk, simply to use up the budget, is inexcusable. The Committee notes that the funding of £232,000 became available in November 2004, and this, in our view, gave BELB ample time to use the normal procurement process.

Recommendation 13

39. The Committee insists that public bodies must not set aside key safeguards for ensuring value for money simply to make sure that funding is spent before the year end.

Education and Library Boards failed an assessment of their status as “Centres of Procurement Expertise" in 2005

40. All Boards were established as COPEs in May 2002, although this status was awarded for goods and services and not maintenance work. Nevertheless, the public would have drawn confidence from the award and retention of COPE status and the fact that such an organisation is operating under the direction of the Procurement Board for Northern Ireland.

41. The Committee’s most recent report[3] on Financial Management in the Further Education Sector recommended that the procurement of all significant expenditure by FE Colleges from third parties should be administered by a COPE. The Committee considered that this would lead to economies of scale and would assist in ensuring that proper procedures are followed. In our earlier report on the Use of Consultants[4] the Committee strongly advocated the use of COPEs and recommended that all contracts are negotiated through them by procurement experts.

42. Given the importance the Committee has placed on the assurance provided by COPE status, it was shocked to discover the absence of normal procurement procedures in BELB. In the 2003 competition for contractors to appear on a select list for minor works, applications were opened as they were received; assessment criteria was drawn up months after the receipt of applications; and applicants were awarded points for information that had not been requested. The Chief Executive told the Committee that members of staff involved in drawing up the 2003 select list were not disciplined because his investigation into the matter found no evidence of manipulation. However, the Committee notes that the Department was so concerned at how the list had been drawn up that it required BELB to suspend its use. Despite this, the list was used in error on seven occasions. The Chief Executive told the Committee that he was satisfied that this was as a result of “a purely administrative error" although he accepted this should not have happened and had apologised to the Accounting Officer.

43. The Committee was reassured to learn from the Treasury Officer of Accounts that the Boards failed the independent assessment of their COPE status in 2005. It would have been incomprehensible if any organisation with the weaknesses the Committee have seen had passed. However, the Committee notes that all Boards were nevertheless reaccredited as COPEs in 2006, as a result of a decision to work with them to secure improvement. While the Committee accepts this may have been the best course in the circumstances at the time, it is vital for the future that COPEs are independently and rigorously assessed.

Recommendation 14

44. The circumstances of this case made the Committee question what one would have to be guilty of to lose accreditation as a centre of procurement expertise. The Committee recommends that COPEs which demonstrate persistent poor practice should have their status removed, if the concept of a “Centre of Procurement Expertise" is to mean anything.

The Department has considered how maintenance procurement will be delivered under the Education and Skills Authority

45. The Department told the Committee that the Education and Skills Authority (ESA) will bring all schools procurement under the responsibility of a single strategic director of procurement, a post which will be filled by summer 2009. The importance of developing better links between each of the Boards, in terms of procurement and carrying out work on a regional basis, was one of the key points of the C&AG’s 2001 report on Building Maintenance in the Education and Library Boards[5] to which the Accounting Officer referred. He told the Committee that the recommendations of this report had not been fully implemented. The establishment of ESA from January 2010 should lead to a region-wide approach, delivering an effective process in an area such as maintenance and allowing the achievement of clearly defined targets.

Recommendation 15

46. The Committee notes that the COPE status of ESA will be reviewed within a year of its establishment. Given the scale of the historic problems within BELB, the Committee recommends that this assessment of COPE status must be rigorous and independent.

47. The Accounting Officer explained that Northern Ireland must in future have an integrated strategy for estates management. In the past, maintenance budgets have been an afterthought and have been cut as a result of other pressures in the sector. As a result, there is now a maintenance backlog of £200 million in the schools estate. This is unacceptable. The Committee notes that a priority for the Department will be to set ESA targets to reduce this backlog to a more “reasonable" level.

Recommendation 16

48. The Committee recommends that ESA draws up an Action Plan for maintenance procurement, drawing on the recommendations of this report.

Representations from a Contractor

49. The Committee asked the Chief Executive how the Board dealt with the poorly performing contractors referred to in the Audit Office report. He told the Committee that civil legal proceedings were active, and that his legal advice was that he should be extremely careful about what he said. Subsequent to the evidence session, the Committee received a submission from one of the contractors expressing his concerns with the Audit Office report. It should be noted that, in clearing the report, this contractor had been given the opportunity to comment. However, this offer was declined.

50. In his opening statement to the session, the Chairperson particularly emphasised that

“the purpose of this session is to use the case study material to consider any shortcomings in the actions of the Departments and the Board, and not to investigate the conduct of any private individual or firm".

Recommendation 17

51. The Committee recommends that there must be absolute clarity in every area of public purchasing that there are no circumstances where it is acceptable to solicit or provide invoices stating that work has been done where it has not.

The Investigation of

Suspected Contract Fraud

52. It is important that good practice guidance on how public bodies should handle suspected fraud is continuously developed, reviewed and circulated widely. Reports such as this by the Committee are intended to assist this process.

Good practice guidance was not implemented

53. The Department confirmed that BELB received a wide range of anti-fraud and procurement guidance from DFP. In 1997, DFP issued specific guidance on Estate and Building Services Procurement, which set out the basic principles of control necessary to minimise the risk of fraud in building services. The principles included:

- separation of duties between staff who place orders, receive services and authorise payments;

- authorisation by a manager/supervisor before activities are undertaken;

- competitive tendering as the norm; and

- regular supervision involving regular and unannounced checks of transactions.

The Accounting Officer confirmed that this guidance was made available to the Boards; it simply was not followed in the cases the Committee examined.

54. The Department also told the Committee that its Internal Audit works actively with its counterparts in the Boards to make sure that best practice contained in the guidance and other publications and disseminated at workshops and seminars, is followed.

55. It is disappointing to note from the C&AG’s report that BELB had developed an anti-fraud policy and fraud response plan in 2000, but the policy, particularly in relation to line managers’ responsibilities, was not fully implemented. Line managers failed to ensure that all staff were provided with fraud awareness training specific to the business area in which they are employed. They failed to minimize opportunities for fraud by using measures such as rotation of staff in key posts and separation of duties. In addition, BELB failed to ensure that staff nominated to carry out initial enquiries and full investigations had received appropriate training, which complied with the provisions of the Police and Criminal Evidence (NI) Order 1989.

56. It is clear from the witnesses that the use of signed declarations of non collusion, which is good practice in tackling bid rigging, is a requirement in contracts. The Committee notes that there was less certainty that declarations are always used or that specific investigations have been undertaken into bid rigging. The Committee asked the Department whether the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) guidance on tackling bid rigging has been made available in the Department and its arm’s-length bodies. The Committee was concerned that DFP could not confirm that the 1998 OFT guidance, referred to in the C&AG’s report, was issued to departments. However, the Committee notes that OFT’s further guidance on bid rigging had issued in April 2008.

57. The Chief Executive told the Committee that all contractors signed declarations of non collusion. While this may have been the case, the Committee is not persuaded that the declarations were working as intended. The C&AG’s report clearly demonstrates that a small group of contractors were consistently receiving highly favourable treatment. The Committee notes that this is a strong indicator that collusion may have been taking place and, in our view, should have alerted BELB about the effectiveness of their non-collusion declarations.

Recommendation 18

58. It is pointless issuing anti-fraud guidance unless it is properly implemented. The Committee recommends that all public bodies should periodically revisit their anti-fraud guidance, including the safeguards and checks on bid-rigging, and ensure that these are being implemented effectively.

Whistleblowers’ allegations were not adequately handled

59. In the Committee’s view, the schools’ maintenance case study strongly underlines the potential value of information from whistleblowers and the importance of investigating any concerns promptly and professionally. The Department’s action in ensuring anonymity of the whistleblower was commendable good practice.

60. The Committee notes that the leads provided by the whistleblower in August 2003, did not ultimately produce the level of evidence needed to pursue prosecutions. Nevertheless, the whistleblower’s concerns were amply vindicated in terms of, for example, poor systems and controls; poor value for money; conflicts of interest; worryingly suspicious patterns of awarding contracts; and no emphasis on avoiding or detecting bid rigging cartels.

61. Against this background of managerial weakness in property maintenance, it is not surprising that successive investigators could not produce firm evidence of fraud. However, the Committee agrees with one of the investigators that “if the whistleblower had not made the allegations these [issues] would have gone undetected and if left unresolved would leave the Boards open to abuse..."

62. This is not the first time that the Committee has emphasised the important role that whistleblowers can make to the identification of potentially fraudulent activity. A previous report on Tackling Public Sector Fraud[6] recommended that much more emphasis should be given to whistleblowing as an important means of identifying fraud. DFP was required to ensure that all departments and agencies had whistleblowing policies. DFP was also expected to ensure that departments are proactive in training and encouraging staff to blow the whistle, and to include an analysis of activity levels of whistleblowing across departments, as part of its annual Fraud Report.

Recommendation 19

63. The whistleblower’s role was central to triggering the investigation in this case. The Committee recommends that Audit Committees be informed of any whistleblowing cases and how they are handled, and that DFP take the opportunity to draw attention to this case in its next annual fraud return, and that any future training on fraud awareness pays particular attention to the value and effective use of whistleblower information.

64. In the Committee’s view, the failure at the outset to have a properly resourced investigation of the allegations made by the whistleblower to the Department in August 2003 may well have contributed to the inability to bring criminal or civil charges in this case. The Committee recognises that generally the interventions of the Department were well directed at strengthening the investigation process and trying to ensure that it was as effective as possible.

Recommendation 20

65. The Committee recommends that whenever a sponsored body is investigating allegations of serious suspected fraud, the sponsoring department should ensure that its own expertise is available with whatever other expertise is required, to assist in the investigation, and the department’s Accounting Officer must, of course, be satisfied that the process is thorough and professional.

66. The Committee acknowledges the whistleblower’s role in triggering the investigations and commends their decision to come forward. The Committee is keen to encourage contributions of this nature.

67. The Department told the Committee that it has further developed its whistleblowing policy, proactively raising staff awareness and the protections afforded to whistleblowers. It also encourages whistleblowers to come forward and made sure the contractor was protected under that policy. Moreover, the Department engaged with the whistleblower to review how the process could work better, and as a result of this interaction, changes have been introduced in its whistleblowing policy. The Committee commends the Department’s handling of the whistleblower in this case.

Recommendation 21

68. The Committee has made it clear that it expects public bodies to operate effective whistleblowing policies; proactively encourage and promote those policies; and rigorously investigate all whistleblowing concerns. The Committee recommends that DFP should draw attention to the Department’s handling of this whistleblower as a model for any future cases.

69. The Committee is disturbed to find that BELB did not effectively handle the investigations of two earlier anonymous letters of November 2002 and February 2003, which had raised concerns of corruption and bid rigging. The investigation of the first of these allegations was led by BELB’s Head of Property Services, assisted by Internal Audit, who found no evidence of a cartel or corruption. BELB told the Committee that its findings were based on a review of all the tendering that was done around certain jobs.

70. The Committee is concerned to note that the Head of Property Services in BELB was allowed to lead the investigation into the November 2002 whistleblower letter. In permitting this, BELB compromised the independence of the investigation and failed to pick up the lessons of an earlier PAC report of June 2002 on Internal Fraud in the Local Enterprise Development Unit. That report clearly recommended that the terms of reference of fraud investigations should not be determined by the management of the business unit but by completely independent officers.

Recommendation 22

71. The Committee is very concerned that it has to repeat a previous recommendation that all members of an investigation team, including its leader, should be totally independent of the management of the business unit where the fraud or suspected fraud occurs.

72. The Committee is very concerned to find that the second letter containing a serious allegation of bid rigging was not even investigated. What is also surprising is the fact that the Department was aware of at least one of the two anonymous letters but does not appear to have intervened.

73. There does not seem to have been a rigorous process by BELB and the Department to follow through on these two letters, and while BELB has made it clear that it welcomes whistleblowers, the failure to act decisively in these matters is a particularly unsatisfactory aspect of the handling of this case.

Recommendation 23

74. BELB should have initiated independent investigations of these letters which could have dealt with the matter properly. The Committee recommends that where a whistleblower makes serious allegations of fraud, management must respond by conducting an appropriate investigation.

BELB failed to guard against the high risk of fraud

75. The Chief Executive told the Committee that until 2006 maintenance work in schools was undertaken using a day-works contract; a type of contract that was used widely in the public and private sectors at the time. In his evidence, he stated that BELB minimised the risk to fraud after 2006 by moving to measured-term contracts, reducing the number of contractors used from 100 to 5. These contracts are now used as standard practice. The Chief Executive claimed that the move to measured term contracts has reduced the opportunities for bid rigging and the operation of cartels because pre-agreed payment schedules exist for the work; the same price is charged whether a job takes one hour or one week.

76. The Committee welcomes the actions that have been taken but experience indicates that fraudsters are adaptable and will quickly look for ways to exploit any new measures that are introduced. The C&AG’s report indicated that BELB’s Risk Registers (at the Corporate and Departmental level) record fraud as a risk to the organisation as a whole but there is no detailed analysis of the risk of fraud in Property Services. The Committee is surprised that those responsible for managing Property Services and devising its Risk Register had failed to recognise the very high threat that fraud poses for them, and the absolute necessity to have a range of strong measures in place to manage that specific threat.

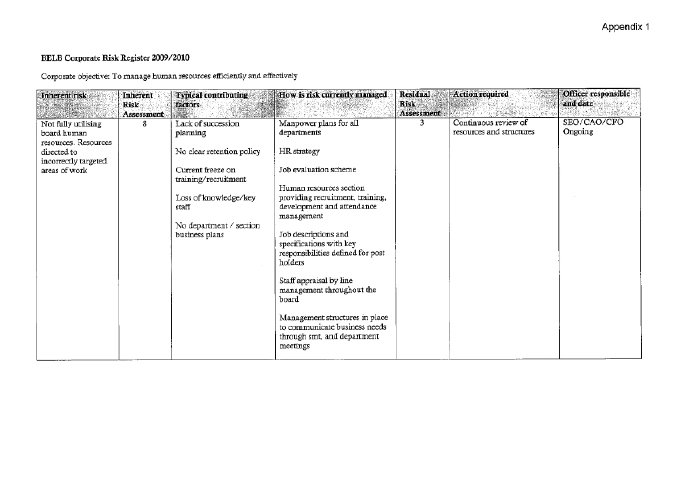

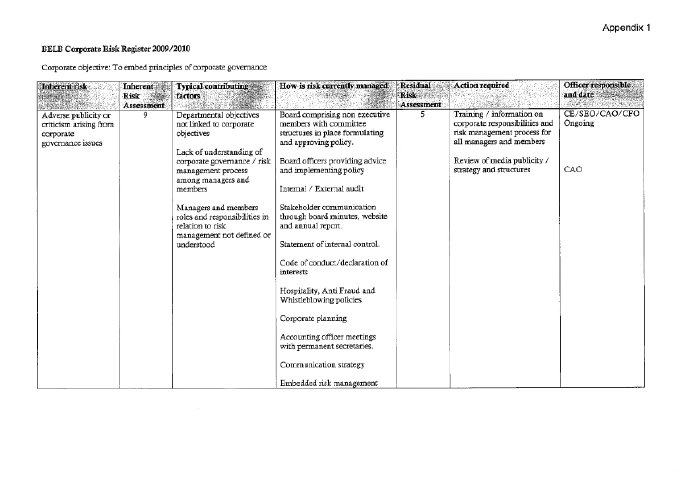

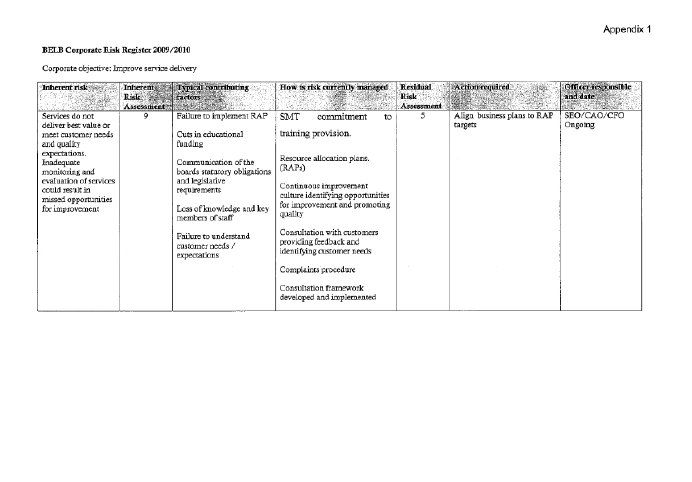

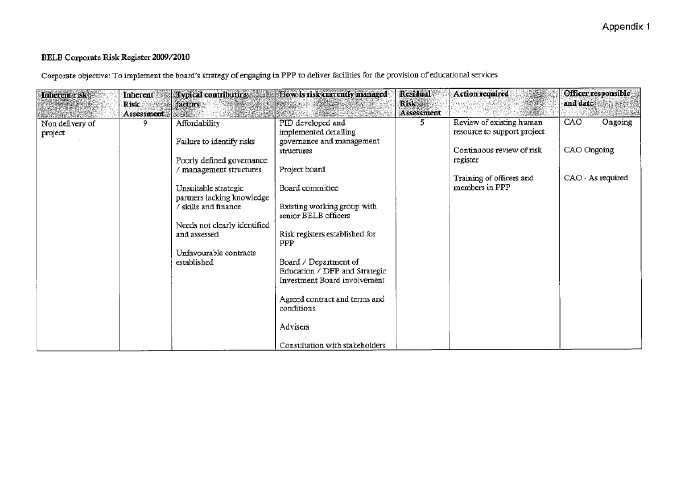

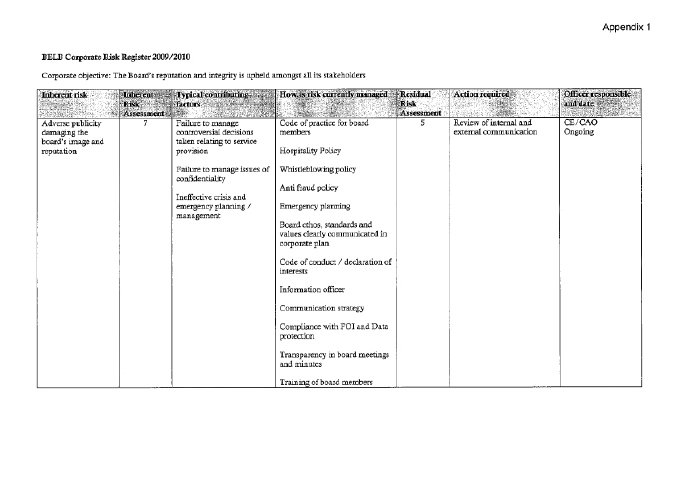

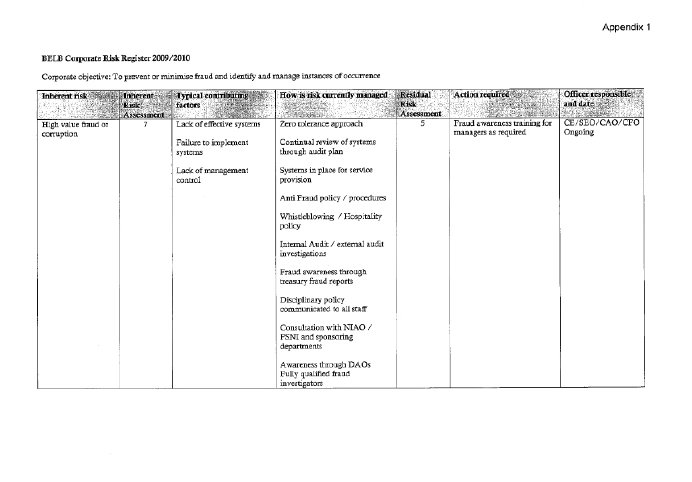

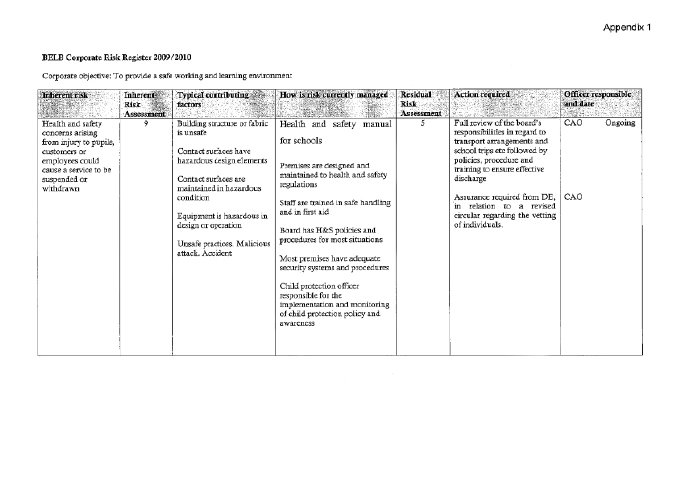

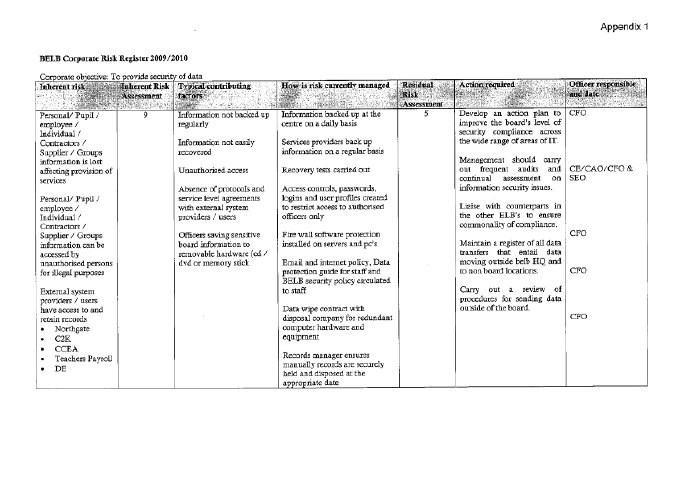

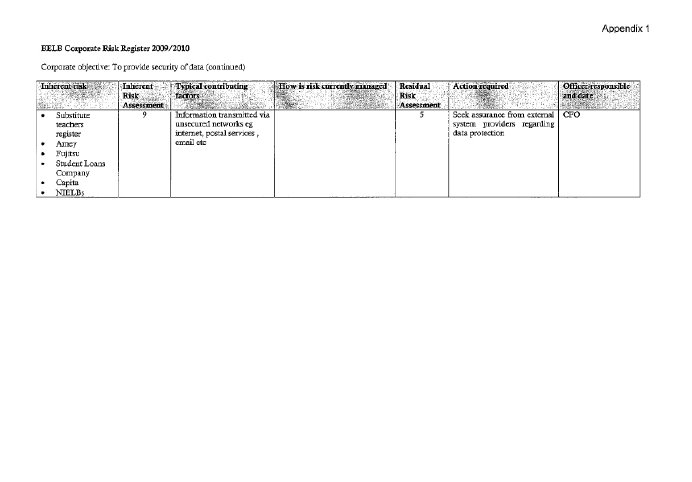

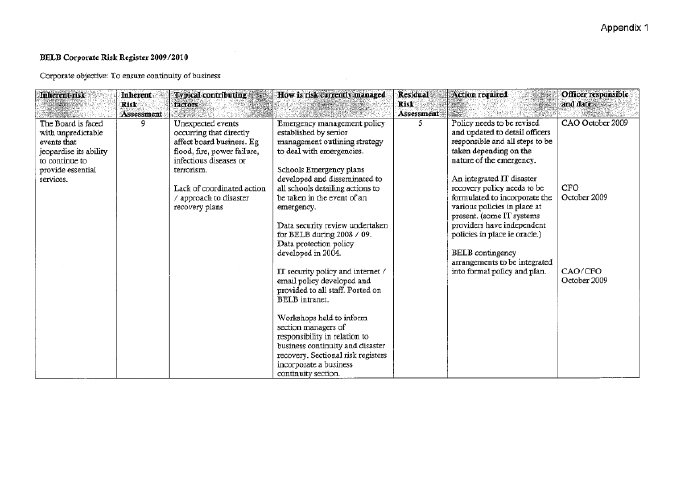

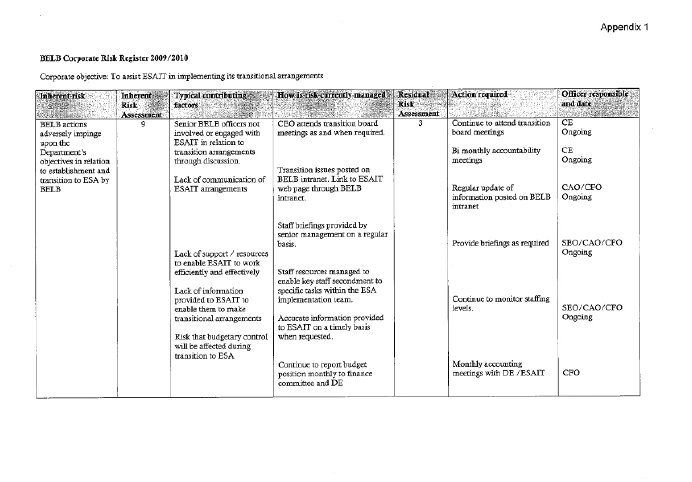

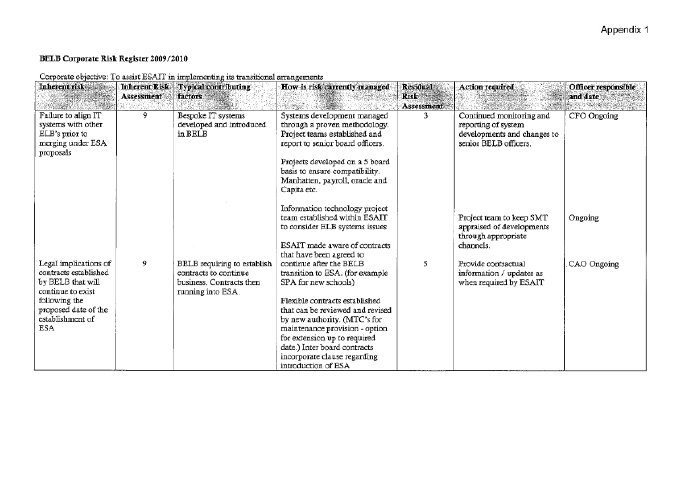

77. Given the high risk of fraud and the recent changes to its maintenance procurement procedures, the Committee asked to examine the Risk Registers. The Corporate Risk Register provided by BELB did not shed any new light on its analysis of fraud. The Committee would have liked to have seen the Property Services Risk Register to assure itself that it had been updated since the C&AG’s report and that the risks in this area are being addressed.

Recommendation 24

78. Fraud Risk Registers are living documents that provide snapshots over time of an organisation’s management of fraud risk in the face of changing circumstances. The starting point for the creation of the Risk Register is a proper fraud risk assessment. The Committee recommends that every public body with maintenance expenditure in excess of £1 million per annum should ensure that the risk of fraud in this area is specifically dealt with in its risk assessment, and the outcome reflected in its Risk Register.

Weak disciplinary action sent the wrong message to staff

79. Three officers in the schools’ maintenance case faced disciplinary charges. The Department’s expert in disciplinary matters concluded that, for two officers, the relationship with a contractor “amount to wilful neglect of the financial and contractual interest of the Board" and that this “represented gross misconduct". However, the officers received a formal written warning which was to be removed from their record after one year. In the libraries case, a supervisor received a final written warning for serious misconduct. Again this was removed from his record after one year. In the Committee’s view, the public perception of these disciplinary measures, when they are removed after a relatively short time, is that they are too light.

80. The Committee also noted comments from witnesses that there are differences between disciplinary processes in BELB and the Northern Ireland Civil Service.

Recommendation 25

81. The Committee recommends that any anomalies in disciplinary procedures in the public sector are reviewed and addressed appropriately.

82. The Committee is concerned that the Disciplinary Panel in the schools’ maintenance case, with all the evidence before it including the consultant’s report, downgraded the offences from gross misconduct to misconduct. Such panels should include members who have experience in the investigation of collusion in order to understand that direct evidence proving a relationship between BELB officers and contractors is unlikely to be available. The evidence in this type of case is most likely to be in terms of outcomes. In this case, for example, an analysis of the outcome of the process showed that maintenance officers had blatantly disregarded very clear instructions to rotate contractors, and had favoured the most expensive contractor by awarding the firm the highest value of emergency work and the second highest value of response work.

Recommendation 26

83. The Committee recommends that, where there is strong evidence of wilful neglect of duty by staff, management should be prepared to place considerable weight on facts of this nature, as evidence of possible gross misconduct. To do otherwise does not send the right signal to staff. In addition, DFP should consider whether sponsoring departments should be represented on disciplinary panels, where suspected fraud is under consideration in their arm’s-length bodies, to add the weight of their greater experience in handling such serious issues.

84. In the libraries case study, which concerned the work paid for but not done in libraries, the officer who managed the work was suspended on full pay in 2005; his employment was terminated in 2007 on ill-health grounds; and the disciplinary case against him was wound up.

85. The witnesses explained that the question of ensuring that staff do not use ill health to avoid disciplinary procedures is complex as disciplinary procedures are subject to natural justice. However, this is not the first case the Committee has come across where disciplinary action has been stopped on medical grounds.

Recommendation 27

86. The Committee recommends that DFP should review a sample of cases from across the public sector of early retirements for reasons of ill-health or inefficiency where disciplinary proceedings are outstanding. The purpose of the review should be to identify whether there is scope to speed up disciplinary proceedings or to improve the handling of such cases, including early notification to Occupational Health Service that a disciplinary/grievance process is under way, and analysis of implications for line management. The Committee would like to know the outcome of this review.

Failure to commend officer

87. The Committee is concerned at the weak disciplinary action taken against those responsible for the failures set out in this report. However, it also notes that when the witnesses were asked about the commendatory action for the individuals responsible for identifying that library works had been paid for but not done, the response was simply that they were a “valued member of staff". The Committee is concerned that this style of management, where there are weak penalties for wrongdoers and even weaker commendation for those doing their job properly, may be all too typical of public sector bodies.

Recommendation 28

88. This Committee has already recommended that whistleblowers should be encouraged and supported to engender a healthy anti-fraud culture. It is also important however, that public sector leaders ensure that staff whose actions lead to the identification of potential fraud and impropriety are explicitly commended, and the Committee recommends that their efforts are recognised appropriately.

Action to recover public money

89. The Department’s consultant reported that he found evidence of consistent overcharging by a contractor undertaking schools’ maintenance work. However, the evidence was not strong enough to support criminal charges. The Committee recognises that this makes recovery action much more difficult. Nevertheless, it is important that every possible action is taken to recover sums overpaid or paid for work not done.

90. In the libraries case the Committee is concerned that the absence of documentation undermined any criminal case. The DCAL Accounting Officer agreed with the Committee that this was an unsatisfactory outcome. He explained that exhaustive efforts were made to bring justice to bear, but there was a lack of documentation, which led the investigators to conclude there was an insufficient basis to take forward criminal action likely to succeed in court. However, legal proceedings are being actively progressed in order to recover moneys from two contractors for work not done.

Recommendation 29

91. The Committee recommends that BELB should consider pursuing legal action in respect of other library works not done or not carried out to the required standard. The Committee would like to be kept informed of progress.

The Department has sought to learn the lessons

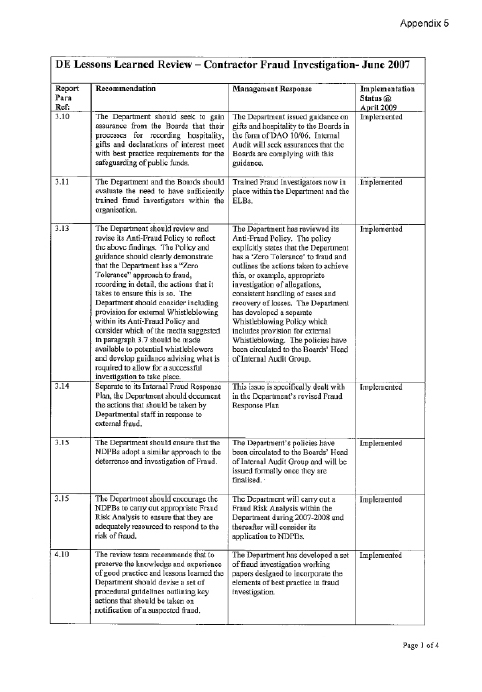

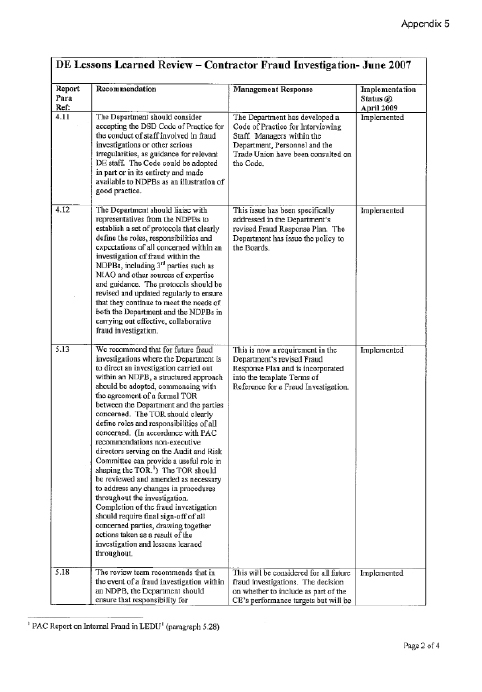

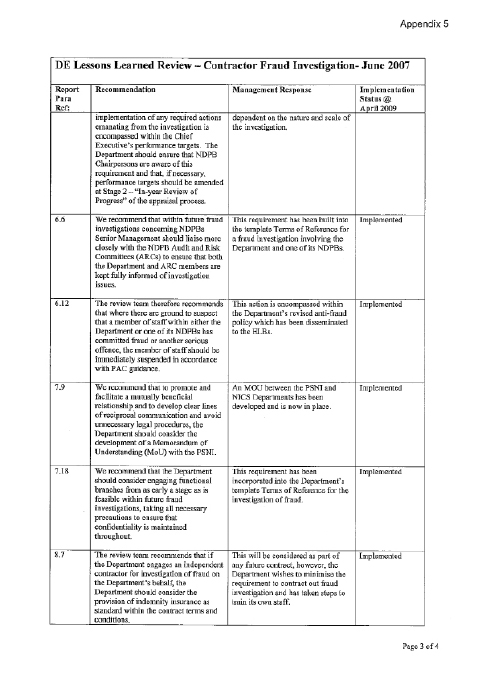

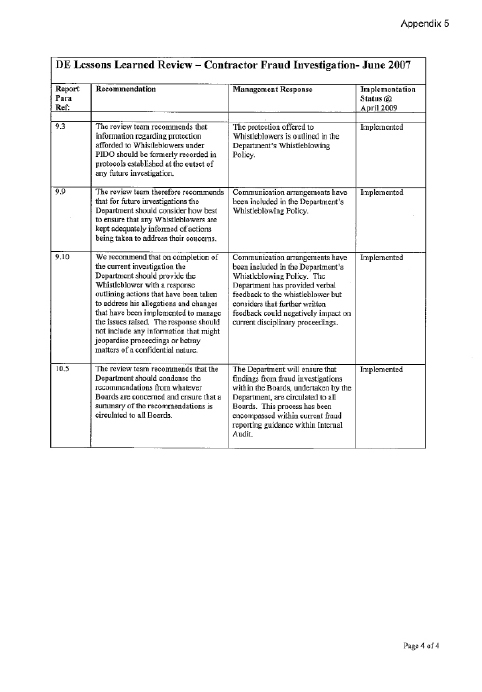

92. The Committee is pleased that the Department has sought to learn lessons from its performance in investigating the whistleblower’s allegations. It identified 20 recommendations and these are set out in Appendix 3 of the Accounting Officer’s correspondence.

93. The witnesses made the point that rigorous control systems must be complemented by effective intervention, and that vigilance is key. They recognised that the investigation took too long to reach a conclusion and should have been taken forward more rapidly. The Committee agrees with this assessment. It should not have been necessary to undertake more than one investigation into the schools maintenance. One properly resourced and planned investigation should have been sufficient to deal with the matter authoritatively. The Accounting Officer accepted the lessons arising from the investigations should have been implemented more quickly and that significant good practice from these case studies should be widely disseminated.

94. The Department also recognised the importance of having the capacity to undertake in-depth investigatory work when fraud is suspected. It told the Committee that it now has five trained fraud investigators; BELB has four; and the other Boards have made sure that training of such investigators is in place. This is commendable. The Department also told the Committee that across the education sector it has strengthened fraud awareness; improved its anti-fraud policies and skills base; and it has investigated between eight and eleven cases over the last two years.