Session 2008/2009

Twelfth Report

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE

Report on the Control of Bovine Tuberculosis in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the committee

relating to the report and the minutes of evidence

Ordered by the Public Accounts Committee to be printed 11 June 2009

Report: 40/08/09R (Public Accounts Committee)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

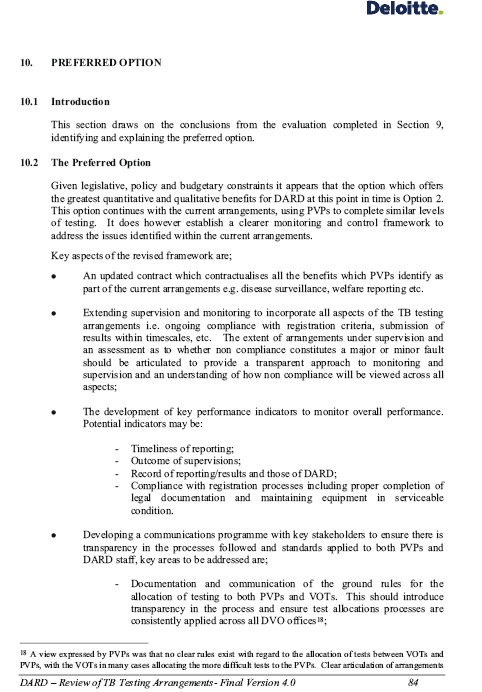

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts and reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 51 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Paul Maskey*** (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns** Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr Jonathan Craig Mr George Robinson****

Mr John Dallat Mr Jim Shannon*****

Mr Trevor Lunn Mr Jim Wells*

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke on 1 October 2007

* Mr Ian McCrea replaced Mr Mickey Brady on 21 January 2008

* Mr Jim Wells replaced Mr Ian McCrea on 26 May 2008

** Mr Thomas Burns replaced Mr Patsy McGlone on 4 March 2008

***Mr Paul Maskey replaced Mr John O’Dowd on 20 May 2008

****Mr George Robinson replaced Mr Simon Hamilton on 15 September 2008

*****Mr Jim Shannon replaced Mr David Hilditch on 15 September 2008

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report

Report

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

Introduction

The Level and Cost of Tackling Bovine Tuberculosis

Testing for Bovine Tuberculosis

Preventing the Spread of Bovine Tuberculosis

EU Matters

Compensation, Enforcement and Tackling Fraud

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2:

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3:

Chairperson’s letter of 31 March 2009, to Dr Malcolm McKibbin, Accounting Officer, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

Correspondence of 16 April 2009 from Dr Malcolm McKibbin, Accounting Officer, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

Chairperson’s letter of 27 March 2009 to Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel

Correspondence of 8 April 2009 from Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel

Chairperson’s letter of 6 April 2009 to Chief Executive, Ulster Farmers’ Union

Correspondence of 4 April 2009 from Mr Colin Smith, Policy Officer, Ulster Farmers’ Union

Correspondence of 10th April 2009 from Mr Michael Woodside, President, The Association of Veterinary Surgeons Practising in Northern Ireland and Mr David S Collins, President, North of Ireland Veterinary Association

Appendix 4:

List of Witnesses

List of Abbreviations

used in the Report

Bovine TB/bTB Bovine Tuberculosis

The Department/DARD Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

EU European Union

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

PVPs Private Veterinary Practices

DEFRA Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

UFU Ulster Farmers Union

AVSPNI Association of Veterinary Surgeons Practising in Northern Ireland

NIVA North of Ireland Veterinary Association

BSE Bovine spongiform encephalopathy

PSA Public Service Agreement

UK United Kingdom

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. Bovine Tuberculosis (bovine TB) is an infectious, bacterial disease which affects the health and welfare of cattle, lowers productivity and fertility and impacts on herd keepers’ profitability. Actions to combat the disease include:

- regular testing of herds for the presence of the disease;

- slaughter of animals positively reacting to the test; and

- movement restrictions on farms where the disease is present.

2. Bovine TB has been a long-standing major problem in Northern Ireland, with at least one quarter of the 25,000 herds of cattle here having had the disease. From 1997, there was a significant increase in cases of bovine TB, rising from just under 5 per cent of herds in 1997 to a peak of some 13 per cent in 2002, the highest bovine TB level in Europe. By 2007, herd prevalence had reduced to just below 7 per cent although, in 2008, there was a slight increase in incidence. Over the past 10 years, the Department has spent some £200 million on its bovine TB control programme. The cost in 2007-08 was over £21 million.

Overall Conclusions

3. The Committee’s overall conclusion is that the Department’s progress in tackling bovine TB has been much too slow and the resulting costs prohibitive. The disease has been a major problem in Northern Ireland for more than two decades – this is far too long. While progress has been made in reducing the incidence of bovine TB in recent years, the level remains significantly higher than in 1996 and many times greater than the 1986 level.

4. The Committee acknowledges that the eradication of bovine TB in Northern Ireland represents a major challenge. Unfortunately, the evidence shows that, in several key respects, the Department has failed to meet that challenge. If the Department is to make real progress, it must adopt a much more strategic approach, with a clear focus on eradication of the disease rather than mere containment. It will also have to work much more closely with both the cattle industry and private veterinary practitioners than it has done in the past.

The level and cost of bTB

5. From 1997, there was a significant rise in incidence of bovine TB. Peaking at some 13 per cent in 2002, this was the highest level in Europe. It appears to the Committee that, for several years, the Department lost a large measure of control over its bovine TB programme, leading to the substantially higher levels of the disease. While external factors played a part, the Department has conceded that it was also at fault.

6. In 2004, the Department’s failure to fully implement the control procedures on bovine TB was strongly criticised by the EU, who reported a lack of commitment. The Department conceded to the Committee that its programme will not lead to the eradication of bovine TB, but said that it is moving incrementally towards a position where it hoped to make greater inroads into eradication. This is a damning admission. Spending £200 million over a 10-year period, merely to contain a disease and with no end to the problem in sight, is poor value for taxpayers’ money.

7. The Department decided in April 1999 to carry out a formal review of its bovine TB eradication policy. However, the review was not completed until 2002 and, since then, progress has been slow, with a number of recommendations still not implemented. While the Department has said that some recommendations are dependent on legislative change which has been delayed with the return of devolution, the Committee cannot accept as reasonable that a policy review process, which began in 1999, is still incomplete some 10 years later.

Testing for Bovine TB

8. At various times between 2002 and 2006, the Department reported serious concerns about the quality of testing carried out by private vets. Indeed, the Department considered that its failure to make real progress in the eradication of the disease was due, at least in part, to poor testing by private vets. In the Committee’s view, this also points to a lack of supervision and control by the Department. It must ensure that, in future, its supervision of private vets is more effective than in the past and that lapses in standards are dealt with on a timely basis.

9. The Committee notes the veterinary associations’ views about damage to the integrity and reputation of the veterinary profession, through recent press coverage of the Department’s concerns about TB testing carried out by private vets. It is the considered view of the Committee that private vets have made an important and major contribution to the Department’s bovine TB programme and that, in most cases, they have diligently carried out their responsibilities. Nevertheless, the evidence does show that, on occasion, not all private vets have managed to meet the high standards required. The associations and their members, particularly practice principals, have a vital role to play in working with the Department to ensure that standards are maintained throughout the profession.

10. The Committee has major concerns about one particular case where a private vet falsely signed for tests performed by an unauthorised vet – a fraudulent act and a serious breach of contract. Yet the Department failed to terminate his contract and report him to his professional body. Moreover, it allowed him to resume working a year later. The Committee does not agree that this was a proportionately severe sanction and is dismayed that the Department should send the message that it is soft on improper behaviour.

11. The Department’s review of bovine TB testing arrangements has made slow progress. Although the review was recommended in 2002, it took until 2005 to engage consultants. The consultants reported in 2006, recommending a range of improvements to testing arrangements but, as yet, these have not been implemented. Given the importance of the review to the conduct of the bovine TB programme, this is indefensible. The Department must develop a much keener sense of purpose.

Preventing the Spread of Bovine TB

12. In 2002, the Department highlighted that inadequate boundary fencing was a major impediment to the successful control and eradication of bovine TB and noted that 79 per cent of fencing did not prevent nose-to-nose contact between herds. The Committee asked for an up-to-date figure but the Department could not provide one. Given that poor boundary fencing appears to have played a significant role in the spread of bovine TB, it is disappointing that the Department does not have a clear view of the extent of the problem. It needs to get a much tighter grip on this issue.

13. Departmental analyses indicated that almost one quarter of bovine TB breakdowns were caused by purchasing infected animals. The shortcomings of the skin test in detecting disease means that there is still a significant risk of purchasing infection, even from herds classified as ‘officially tuberculosis free’. Despite this, the Department has repeatedly decided against pre-movement testing, largely due to the costs involved. In the Committee’s view, the Department should not rule out some form of cost-sharing with the cattle industry as a future option. Hastening the eradication of bovine TB is very much in the industry’s interests also.

14. A reservoir of infection in wildlife, particularly badgers, has long been thought to be a factor in bovine TB transmission. However, to date, the Department has not actually intervened to tackle the wildlife issue. The Committee is concerned about the timescale for future progress and is not wholly confident that the Department is committed to moving this issue forward as quickly as it would like. The Committee recognises that this is an emotive issue which has not been objectively answered. When the badger prevalence survey is completed and the way forward determined, the Committee expects real progress to be made with a minimum of delay.

EU Matters

15. The Department told the Committee that the isolation of reactors is still a difficult problem in a number of herds, with farmers facing major logistical difficulties, particularly in dairy herds or where animals are in housing. The Committee finds this worrying. It is incumbent upon the industry to meet the requirements of the EU Directive and it is most unsatisfactory that there are farms not properly equipped to apply the standard control procedures.

16. The Department is still not complying with the EU Directive on inconclusive test results - it allows two re-tests rather than the one permitted by the EU. While the Department has explained that compliance would cost £1.1 million annually, this appears to the Committee to be a false economy. Through its non-compliance, the Department has cut itself off from additional funding made available by the EU to help eradicate disease – no funding was secured from the EU Veterinary Fund in five of the nine years from 2000 to 2008. The Committee recommends that the Department address its failure to secure what would have been millions of pounds worth of grants from the Fund.

Compensation, Enforcement and Tacking Fraud

17. There were a number of cases where multiple compensation claims had been paid to the same herd owners. The Committee recognises that it can be difficult to eradicate bovine TB from herds but is concerned whether a 100 per cent compensation rate provides sufficient incentive for herd owners to prevent infection. In the Committee’s view, the cost of repeated disease breakdowns rests almost entirely with the taxpayer, and this cannot be right. In such cases, a share of the cost should be borne by the industry.

18. Given the 100 per cent compensation rate, the inherent risk of fraud is high. Most commonly, this involves interference with the test site. Since 2001, 8 cases have been investigated, but only 2 of these were successfully prosecuted. Surprisingly, the two herd owners involved later received compensation for subsequent bovine TB outbreaks. The Committee considers that, as an added deterrent against fraud, the Department should seek to introduce a system of penalties against future compensation claims, where claimants have previously been found guilty of fraud.

Departmental agreement of NIAO Reports

19. The Committee attaches great importance to the C&AG’s reports being agreed by Departments and expects every reasonable effort to be made to do so. The Committee notes that in this case, however, there were some aspects of the C&AG’s report with which the Department said that it could not fully agree. This is the first occasion on which this issue has arisen. The Committee has looked closely at the matters concerned and is satisfied that the points raised by the Department are minor and have little or no bearing on the substantive issues. While the Committee recognises the need for a Department to have its views presented, its expectation is that situations like this will remain very much the exception. Accordingly, the Committee would ask the Department of Finance and Personnel to draw these comments to the attention of all Departments.

Summary of Recommendations

The Level and Cost of Tackling Bovine TB

Recommendation 1

1. Spending hundreds of millions of pounds on a programme that is not explicitly aimed at the eradication of bovine TB seems an extremely poor use of taxpayers’ money. In the Committee’s view, there needs to be a fundamental change in mindset within the Department, with a renewed focus on eradication, not merely containment. The Committee recommends that there must be a marked and sustained reduction in the prevalence of bovine TB and expects to see a much greater sense of urgency within the Department to achieve this (see paragraph 19).

Recommendation 2

2. The Committee recommends that the Department re-examines its bovine TB performance targets. While allowing for a possible increase in incidence in the short-term, targets should be much more challenging in the medium to longer-term than currently and must include a target date for eradication. The Committee accepts that this end date may require revision as the programme develops, but considers it vitally important that the Department has a clear sense of its ultimate objective (see paragraph 20).

Recommendation 3

3. The Committee cannot accept as reasonable that a policy review process that began in 1999 is still incomplete some 10 years later. The Committee recommends that the Department ensure that, in future, policy reviews are carried out at the appropriate time and that the recommendations arising from those reviews are considered and implemented on a timely basis (see paragraph 23).

Testing for Bovine TB

Recommendation 4

4. The Committee recommends that the Department ensures that its supervision of PVPs is more effective than it has been in the past and that lapses in standards are dealt with on a timely basis. In particular, it must ensure 100 per cent compliance with the requirement to report test results within one working day. The Committee recommends that the veterinary Associations and practice principals help bring this about, as a matter of urgency. The Department must also take steps to improve its partnership arrangements with private vets – for example, through more frequent and regular liaison meetings at a local level (see paragraph 30).

Recommendation 5

5. The Committee finds it worrying that significant differences in bovine TB detection rates, between DARD staff and PVPs, have existed over the past 20 years and yet the Department still cannot explain why. The Committee recommends that the issue be resolved and action taken to address the underlying problems as a matter of urgency. In future, test results should be monitored on an ongoing basis, with any anomalies quickly investigated and resolved (see paragraph 31).

Recommendation 6

6. While it is a matter for the Department’s Monitoring Panel to decide on the appropriate penalty, the Committee expects a firm line to be taken in all cases warranting suspension. It is important to make clear to the small number of vets whose performance falls below the acceptable level that the Department is serious about enforcement of standards. Penalties should include the withholding or recovery of fees, as appropriate. The Committee recommends that the Department consider introducing sanctions against veterinary practices, in addition to individual practitioners, for cases involving serious or repeated breaches of procedures (see paragraph 34).

Recommendation 7

7. The Committee has major concerns about one particular case outlined in the C&AG’s report, involving a private vet who falsely signed for tests performed by an unauthorised vet. Not only did the Department fail to terminate his contract and fail to report him to his professional body, but it allowed him to resume working for the Department a year later. The Committee was told that, in making this decision, the Department considered legal advice from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and the finding of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute. The Committee notes that this is not consistent with paragraph 2.27 of the C&AG’s agreed report. The Committee requires the Department to clarify which of these versions in respect of legal advice is correct (see paragraphs 35 and 36).

Recommendation 8

8. The Committee strongly recommends that any vet who is found guilty of fraudulent behaviour should have their contract terminated, be reported to their professional body and, where possible, be prosecuted. Moreover, any vet who has previously been found guilty of fraudulent behaviour should not subsequently be engaged by the Department (see paragraph 38).

Recommendation 9

9. Given the high level of testing in the bovine TB programme, even a relatively small difference in the unit cost of tests can have a significant impact on overall programme expenditure. The Committee recommends that the Department closely monitors the relative costs of in-house and PVP testing on an ongoing basis, to ensure that best value for taxpayers’ money is consistently achieved (see paragraph 43).

Recommendation 10

10. The use of lay testers has the potential to provide a useful new resource, while achieving substantial cost savings over current arrangements. The Committee recommends that the Department reviews the outcome of the DEFRA trial and its discussions with the European Commission. If DEFRA is successful in obtaining approval to lay testing, the Committee recommends that the Department gives full consideration to adopting a similar approach in Northern Ireland (see paragraph 45).

Recommendation 11

11. The Committee recommends that the Department reconsider the current allocation of testing between PVPs and in-house staff, with a view to increasing the proportion of routine tests conducted in-house. This would also provide a better benchmark for the quality review of PVP routine testing, about which the Department has previously expressed concerns (see paragraph 48).

Recommendation 12

12. The Committee recommends that, as a general principle, Departments should never delay taking action on what should be urgent issues, pending completion of an Audit Office report. In this particular case, the length of time the Department is taking to put the findings of its review of testing arrangements into practice is unacceptable. It must finalise its position on each of the issues involved and begin implementation as soon as possible (see paragraph 51).

Recommendation 13

13. It appears to the Committee that there is a strong case for introducing compulsory blood tests in problem and high risk herds. In view of the cost implications, the Committee recommends that the Department considers conducting a trial, in a high incidence area, as a basis for a cost-benefit assessment. Given the need for more research into the efficacy of the blood test, the Committee urges the Department to ensure that sufficient resources are applied to ensure that this work receives a high priority (see paragraph 58).

Preventing the Spread of Bovine TB

Recommendation 14

14. Given that poor boundary fencing appears to have played a significant role in the spread of bovine TB, the Committee is disappointed that the Department does not have a firm grip on this issue. In the Committee’s view, there is merit in obtaining a clear view of the real extent of the problem and the Department needs to consider how this can be tackled. As regards the enforcement of fencing requirements, the Committee recommends that the Department acts on its intention to link non-compliance with biosecurity codes to the level of compensation awarded and expects this to be taken forward as a priority issue (see paragraph 62).

Recommendation 15

15. The Committee considers that the Department should be much more proactive in encouraging farmers to attend training on early disease recognition and farm biosecurity planning and would like to see the number of participants substantially increased. The Committee recommends that the Department makes attendance compulsory for farmers whose herds have suffered repeated infection. Failure to attend should result in a reduction of compensation in future outbreaks (see paragraph 64).

Recommendation 16

16. The Committee recommends that the Department considers introducing pre-movement testing, for animals moving within Northern Ireland, perhaps on a trial basis within a high incidence area. As part of the Department’s consideration, an updated cost-benefit analysis should be prepared. This would also provide a useful basis for opening dialogue with farmers’ representatives on cost sharing (see paragraph 68).

Recommendation 17

17. It is important that the wildlife factor in the transmission of bovine TB is addressed. The Committee recognises that this is an emotive issue which has not been objectively. When the badger prevalence survey is completed and the way forward determined, the Committee expects real progress to be made with a minimum of delay (see paragraph 72).

Recommendation 18

18. The Committee recommends that the Department examines the potential for adopting a “test-bed" approach as a means of determining the most cost-efficient combination of measures to eradicate bovine TB (see paragraph 74).

EU Matters

Recommendation 19

19. It is important that the Department finalises its thinking on how best to address the conflict of interest inherent in PVPs carrying out testing in their clients’ herds. If the conflict cannot be eliminated, the Committee recommends that the Department ensures that the risks are properly managed and that adequate safeguards are put in place. This should include an effective system of monitoring the work of PVPs, supplemented by a programme of robust supervisory checks (see paragraph 80).

Recommendation 20

20. The Committee welcomes the reduction in numbers of overdue herd and individual animal tests in recent years. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement and the Committee recommends that the Department aims to achieve much closer to 100 per cent compliance with the 12-month deadline, for all animals (see paragraph 84).

Recommendation 21

21. The Committee recommends that the Department works closely with the farmers’ representative bodies to see how the problems in isolating reactor animals can best be overcome. Given the problems with isolation, the Committee recommends further reductions in reactor removal time, as well as 100 per cent compliance with the EU 30-day target (see paragraph 88).

Recommendation 22

22. The Committee strongly recommends that the Department brings itself into line with the EU Directive, by allowing only one re-test of ‘inconclusive’ animals (see paragraph 91).

Recommendation 23

23. The Committee recommends that the Department address its failure to secure what would have been millions of pounds’ worth of grants from the EU Veterinary Fund. The Committee wants the Department to be in no doubt that it expects full advantage to be taken, in future, of the funding available from the EU (see paragraph 96).

Compensation, Enforcement and Tacking Fraud

Recommendation 24

24. The Committee recommends that, as an added incentive to prevent bovine TB breakdowns, the Department considers introducing a system whereby the rate of compensation would be progressively reduced in cases of multiple claims by the same herd keeper (see paragraph 101).

Recommendation 25

25. With bovine TB continuing to be a significant problem, it is essential to enforce, and be seen to enforce, compliance with the regulations on testing and movement restrictions. Given the limited success to date of enforcement activity against breaches of the regulations, the Committee recommends that the Department reviews its investigation methods, in order to improve its standard of evidence collection (see paragraph 104).

Recommendation 26

26. There is a disturbing gap between the Department’s rhetoric on zero tolerance to fraud and the effectiveness of its actions. The Committee recommends that, as an added deterrent against fraud, the Department should seek to introduce a system of penalties against future compensation claims, where claimants have previously been found guilty of fraud. The outcome of the Department’s consideration should be provided to the Committee (see paragraph 107).

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee met on 26 March 2009 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report on ‘The Control of Bovine Tuberculosis in Northern Ireland’ (NIA 92/08-09). The witnesses were:

- Dr Malcolm McKibbin, Accounting Officer, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD);

- Mr Bert Houston, Chief Veterinary Officer, DARD;

- Mrs Colette McMaster, Director, Animal Health and Welfare Division, DARD;

- Mr John Dowdall, Comptroller and Auditor General; and

- Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts.

The Committee also took written evidence from DARD, the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP), the Ulster Farmers’ Union (UFU), the Association of Veterinary Surgeons Practising in Northern Ireland (AVSPNI) and the North of Ireland Veterinary Association (NIVA).

2. Bovine Tuberculosis (bovine TB) is an infectious, bacterial disease which affects the health and welfare of cattle, lowers productivity and fertility, and impacts on herd keepers’ profitability. The disease has been a long-standing major problem in Northern Ireland, with at least one quarter of the 25,000 herds of cattle here having been infected. At December 2008, some 1,600 herds (just under 7 per cent of the total) were under disease restrictions. Actions to combat the disease include:

- regular testing of herds for the presence of the disease;

- slaughter of animals positively reacting to the test; and

- movement restrictions on farms where the disease is present.

3. The Department has recently announced that there is to be a new strategic approach to dealing with bovine TB in Northern Ireland. Accordingly, this is an opportune time for the Committee to consider how the Department can improve the measures taken to combat bovine TB. This is particularly important given the substantial level of public funds spent each year on trying to control a disease which, to date, shows no prospect of eradication.

4. In taking evidence, the Committee focused on five key areas. These were:

- the level and cost of tackling bovine TB;

- testing for bovine TB;

- preventing the spread of bovine TB;

- EU matters; and

- compensation, enforcement and tackling fraud.

The Level and Cost of

Tackling Bovine Tuberculosis

The level of bovine TB in Northern Ireland was the highest in Europe

5. Bovine TB has been a significant problem in Northern Ireland for decades. The PAC at Westminster examined and reported on bovine TB in 1993-94. At that stage, the Department was in the midst of a three-year “Enhanced bovine TB Eradication Programme" which aimed to reduce the disease to 1986 levels when, on average, only 0.06 per cent of animals tested were reactors. However, results were disappointing - at the close of the Programme in 1995, incidence levels had increased and were some four times higher than targeted. From 1997, there was a significant increase in cases of bovine TB, rising from just under 5 per cent of herds in 1997 to a peak of some 13 per cent in 2002. This was the highest level of bovine TB in Europe. By 2007, herd prevalence had reduced to just below 7 per cent although, in 2008, there was a slight increase in incidence.

6. Despite the general improvement since 2003, the Department accepted that bovine TB levels were still too high and that much more needed to be done. It highlighted several reasons why bovine TB levels in Northern Ireland are particularly high, including infection in the badger population; intensive farming with a high level of cattle-to-cattle contact; a production cycle that involves different producers at each stage, leading to substantial levels of cattle movement; and the extensive use of conacre, again involving the widespread movement of animals.

7. However, these factors have long been a feature of local farming and do not explain why bovine TB levels rose so sharply from 1997. The Accounting Officer said that, in the late 1990s, veterinary resources had been diverted to deal with other priority issues, including BSE and later, in 2001, Foot and Mouth disease. He also suggested that the increase in bovine TB compensation rates for farmers, from 75 per cent to 100 per cent may have played a part. He conceded, however, that both the Department and private veterinary practitioners had not been carrying out some of their administrative and testing duties in a timely enough manner or with the necessary administrative rigour.

8. It appears to the Committee that, for a number of years from the mid-1990s, the Department lost a large measure of control over its bovine TB programme, leading to substantially higher levels of the disease. While external factors played a part, it is clear that the Department was also at fault – its failure to manage the bovine TB programme with sufficient rigour is unacceptable and must not be repeated.

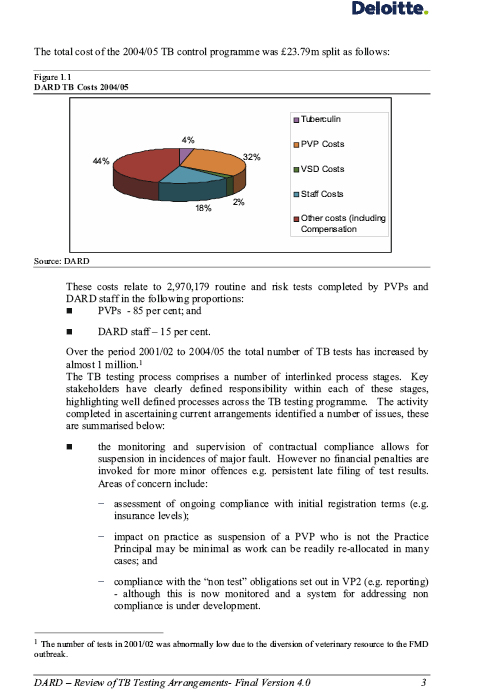

Bovine TB is a major drain on public funds

9. The significant increase in prevalence of bovine TB from 1997 has had a considerable impact on public expenditure. In the 10 years to March 2006, the Department spent a total of £199 million on the bovine TB control programme, including compensation of £86 million to farmers for the compulsory slaughter of animals, payments of £54 million to Private Veterinary Practices (PVPs) for herd testing and staff costs of £43 million. The cost in 2007-08 alone was over £21 million. Despite this huge spend, the Department seems no closer to eradicating the disease than it was 10 or even 20 years ago.

10. The Department argued that expenditure on controlling bovine TB is an ‘investment’, without which the local farming industry would potentially lose £844 million in trade each year. It sees this as a small price to pay. The Committee does not accept this argument. The proper way to protect the cattle industry here is to ensure that it is disease-free – not to spend millions of pounds each year simply to contain bovine TB at a level which remains among the highest in Europe.

11. The Department’s failure to eradicate bovine TB has led to a substantial and ongoing drain on public funds, particularly over the past 10 years. Huge sums are being applied to the programme that are badly needed elsewhere in the industry. This is unacceptable.

DARD’s approach has been to contain bovine TB rather than eradicate it

12. The Department’s policy, since 1964, has been to eradicate bovine TB from the Northern Ireland cattle population. However, in 1995, following the Enhanced Eradication Programme, it considered that eradication was unlikely to be a short-term reality. Eight years later there was little change when, in 2003, it acknowledged internally that in the “short term", its policy was to control bovine TB, within realistic economic constraints.

13. In 2004, the Department’s failure to fully implement EU control procedures on bovine TB was subject to strong criticism from the ‘EU Food and Veterinary Office’. It reported a lack of commitment and considered it highly questionable that the programme could lead to eradication of bovine TB. The Accounting Officer admitted to the Committee that the actions currently being taken by the Department will not lead to the eradication of bovine TB, but said that they are moving incrementally towards a position where they hoped to make greater inroads into eradication. This is a damning admission. It seems to the Committee that, five years after the EU report, the Department is still not firmly committed to the early eradication of bovine TB.

14. The Department also told the Committee that, in order to totally eradicate the disease, more severe restrictions would have to be implemented, but there was real concern about the detrimental effect this would have on the industry. In the Accounting Officer’s view, the Department had to take a pragmatic approach and listen to stakeholders about what is deliverable on the ground.

15. If, in practice, this “pragmatic approach" involves continuing indefinitely with the current high levels of public expenditure, without actually eliminating bovine TB, the Department must think again. There is nothing pragmatic about spending £200 million over a 10-year period, merely to contain a disease and with no end to the problem in sight. This is extremely poor value for taxpayers’ money. The Committee’s concerns were heightened by the Department’s explanation that, in Australia and Denmark, it took 28 and 24 years respectively, to eradicate bovine TB, even after elimination of the wildlife problem. The Department must bear in mind that its own eradication programme has already been in place for 45 years.

16. The Committee noted the Department’s announcement, in December 2008, of a new strategy to tackle bovine TB. The Accounting Officer said that this is being developed in three strands – real partnership between Government and the industry, controlling the spread of bovine TB between cattle and addressing the wildlife factor. While this is a welcome development, it does seem surprising that such basic elements were not put in place long before now.

DARD has concerns that it may not meet its 2011 ‘PSA’ target for reducing the incidence of bovine TB

17. The Department’s Public Service Agreement (PSA) target for bovine TB is to reduce the herd incidence of bovine TB by 27 per cent, by 2011 (to an overall level of 3.9 per cent). The Accounting Officer said that he had concerns over the achievement of this target, explaining that, if the Department were to bring in an enhanced testing programme and adopt a more proactive approach, it would expect disease levels to increase in the short-term.

18. In the Committee’s view, bringing in an enhanced programme and adopting a much more proactive approach should not be seen as optional – it is an absolute necessity. The Committee also questions whether the target of reducing bovine TB incidence by one quarter (27 per cent) over three years is sufficiently challenging for an enhanced eradication programme. The Department needs to take a much more strategic view of the problem and think in terms of eradication of the disease, within a definite timeframe.

Recommendation 1

19. Spending hundreds of millions of pounds on a programme that is not explicitly aimed at the eradication of bovine TB seems an extremely poor use of taxpayers’ money. In the Committee’s view, there needs to be a fundamental change in mindset within the Department, with a renewed focus on eradication, not merely containment. The Committee recommends that there must be a marked and sustained reduction in the prevalence of bovine TB and expects to see a much greater sense of urgency within the Department to achieve this.

Recommendation 2

20. The Committee recommends that the Department re-examines its bovine TB performance targets. While allowing for a possible increase in incidence in the short-term, targets should be much more challenging in the medium to longer-term than currently and must include a target date for eradication. The Committee accepts that this end date may require revision as the programme develops, but considers it vitally important that the Department has a clear sense of its ultimate objective.

The Department’s review of bovine TB policy has been slow

21. The Department decided in April 1999 to carry out a formal review of its bovine TB eradication policy. However, the review was not completed until 2002. The Department said that progress had been delayed due to the Foot and Mouth outbreak in 2001. It seems to the Committee that the review could and should have been completed before Foot and Mouth arose. Given that, in 1999, the incidence of bovine TB was at its highest for well over a decade, the Committee would have expected the Department to have given much greater urgency to carrying out the review, following its decision to re-examine the policy.

22. The C&AG’s report noted that progress in carrying forward many of the Policy Review’s recommendations had been slow, with a number still not implemented some five years later. The Department said that a number of the recommendations were dependant on legislative change but that this process, originally scheduled for 2006-07, has been delayed with the return of devolution.

Recommendation 3

23. The Committee cannot accept as reasonable that a policy review process that began in 1999 is still incomplete some 10 years later. The Committee recommends that the Department must ensure that, in future, policy reviews are carried out at the appropriate time and that the recommendations arising from those reviews are considered and implemented on a timely basis.

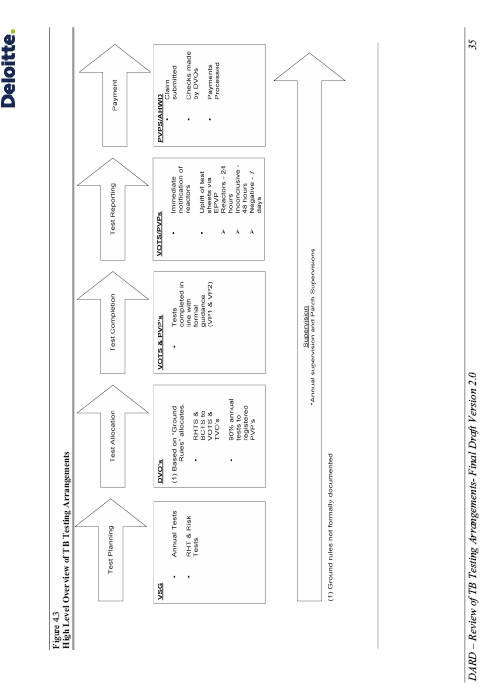

Testing for Bovine Tuberculosis

24. Under EU rules, all cattle herds in Northern Ireland (comprising 1.7 million animals) are required to undergo a “routine annual herd test" for bovine TB. The Skin Test is the EU-recognised standard for identifying the presence of bovine TB in cattle. It produces three types of result – negative, positive (where the animal tested is classified as a reactor), or inconclusive. However, the skin test is not always accurate and fails to detect up to 1-in-4 infected animals. As a result, a reservoir of infected animals can remain within a herd. In addition to routine testing, “restricted herd tests" and “at risk" herd tests are also carried out, where infection is confirmed or suspected. All tests must be undertaken by qualified veterinarians, either by DARD in-house staff or contracted to Private Veterinary Practices (PVPs).

The Department has expressed serious concerns about the quality of testing by PVPs

25. At various times between 2002 and 2006, the Department has reported serious concerns about the quality of testing carried out by PVPs. Concerns were also reported by EU inspectors. In 2003, when bovine TB was at its height, the Department’s Veterinary Service commented that the failure to make real progress in the eradication of TB was due, at least in part, to poor testing by PVPs. This was strong criticism.

26. Specific issues identified by the Department included the late reporting of test results, the testing of exempt animals, failure to check dates of birth, failure to comply with health and safety requirements and the use of out-of-date tuberculin. In the Committee’s view, this also pointed to a lack of supervision and control. The Department said that the position had improved – test results were now being reported on average within 1.7 days, compared with the contract period of one day, and the procedures for exempt animals and checking of dates of birth were now fully compliant with EU rules. The Committee does not accept the Department’s view that the shortcomings noted above only amounted to poor compliance with PVP contracts, but did not affect its bovine TB surveillance programme. Late notification of test results, use of out-of-date tuberculin and wasting time and money on testing exempt animals are bound to impact on the effectiveness of the programme.

27. Another area of concern noted by the Department was that detection rates differ considerably between PVPs and in-house staff. Based on data collected in two comparison exercises over a 10-year period from 1988, it found that, when compared on a like-for-like basis, in-house staff were between 1.5 and 1.8 times more likely to identify bovine TB than private vets. The Department said that more recent analysis had found a similar pattern, although it had not yet established whether the results were representative of the PVP population as a whole or of a smaller sub-grouping. The Department added that differences in detection rates, between groups of in-house staff, have also been found.

28. In terms of improving bovine TB testing, the Committee considers that a number of the points included in the submission from the AVSPNI and NIVA merit consideration by the Department. These include whether the absence of a supervision process for the Department’s staff, similar to that for PVPs, undermines the use of their testing results as a benchmark for PVPs; the instigation of regular meetings between Divisional Veterinary Offices and local practices; and test result statistics of individual vets testing within a practice being made available to practice principals on a regular basis, to facilitate internal quality review. As regards this last point, the Committee finds it astonishing that this is not already a standard procedure, given the long-standing concerns about detection rates.

29. The Committee also notes the veterinary associations’ comments about damage to the integrity and reputation of the veterinary profession, through the recent press coverage of the Department’s concerns about testing carried out by PVPs. It is the considered view of the Committee that PVPs have made an important and major contribution to the Department’s bovine TB programme and that, in the majority of cases, private vets have diligently carried out their responsibilities. Nevertheless, the evidence does show that, on occasion, not all private vets have managed to meet the high standards required. The associations and their members, particularly practice principals, have a vital role to play in working with the Department to ensure that standards are maintained throughout the profession.

Recommendation 4

30. The Committee recommends that the Department ensures that its supervision of PVPs is more effective than it has been in the past and that lapses in standards are dealt with on a timely basis. In particular, it must ensure 100 per cent compliance with the requirement to report test results within one working day. The Committee recommends that the veterinary associations and practice principals help bring this about, as a matter of urgency. The Department must also take steps to improve its partnership arrangements with private vets – for example, through more frequent and regular liaison meetings at a local level.

Recommendation 5

31. The Committee finds it worrying that significant differences in bovine TB detection rates between DARD staff and PVPs have existed over the past 20 years, and that the Department still cannot explain why. The Committee recommends that the issue be resolved and action taken to address the underlying problems as a matter of urgency. In future, test results should be monitored on an ongoing basis, with any anomalies quickly investigated and resolved.

There is scope to strengthen sanctions against poorly performing PVPs

32. The Committee was surprised to learn that no fees had been recovered by the Department in those cases where private practitioners had failed to comply with the terms of their contract or whose work was sub-standard. This is poor practice. Public funds should not be paid where the agreed terms are not met or the work carried out is not satisfactory.

33. In 2005, the Department issued a protocol for the supervision of PVPs carrying out TB testing for DARD. The protocol indicates that, where suspension is appropriate, the period of suspension will normally be between 3 and 12 months. The Committee noted, however, that in practice, a number of suspensions were for two months or less. The Department suggested that these suspension periods may not include the lapse of time between the test date (from which point the vet may effectively be suspended) and the date of the Monitoring Panel meeting which considers the case and determines the penalty. In the Committee’s view, this seems an odd way to record suspension periods. The period of suspension noted in the records should always equate to the total time over which the vet has been suspended, not just the period following the Monitoring Panel meeting.

Recommendation 6

34. While it is a matter for the Department’s Monitoring Panel to decide on the appropriate penalty, the Committee expects a firm line to be taken in all cases warranting suspension. It is important to make clear to the small number of vets whose performance falls below the acceptable level that the Department is serious about enforcement of standards. Penalties should include the withholding or recovery of fees, as appropriate. The Committee recommends that the Department should also consider introducing sanctions against veterinary practices, in addition to individual practitioners, for cases involving serious or repeated breaches of procedures.

35. The Committee has major concerns about one particular case outlined in the C&AG’s report. A private vet falsely signed for tests performed by an unauthorised vet – this was a fraudulent act and a serious breach of contract. Yet, not only did the Department fail to terminate his contract and fail to report him to his professional body, but it allowed him to resume working for the Department a year later. The Committee was told that, in making this decision, the Department considered legal advice from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and the finding of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute. The Committee notes that this is not consistent with paragraph 2.27 of the C&AG’s agreed report. Nevertheless, the Committee does not agree that this was a proportionately severe sanction and is dismayed that the Department should send the message that it is soft on improper behaviour.

Recommendation 7

36. The Committee requires the Department to clarify which of these versions in respect of legal advice is correct.

37. The Committee recognises that such cases will be highly exceptional. Nevertheless, there are important issues at stake. Accordingly, the Committee sought a categorical assurance from the Department that, in future, it will not engage any vet who has previously been found guilty of fraudulent behaviour. Surprisingly, however, the Department commented that it was not prepared to give this assurance and that it would not remove someone’s livelihood for life. The Committee was shocked and takes issue with this statement. In any other area of public life, someone involved in defrauding the public purse would have their employment terminated. In the Committee’s view, the Department’s reasoning on this issue is seriously flawed and at odds with its policy of ‘zero tolerance’ to fraud. Vets are in the forefront of the fight against bovine TB and, as such, their professional integrity must be beyond reproach.

Recommendation 8

38. The Committee recommends very strongly that any vet who is found guilty of fraudulent behaviour should have their contract terminated, be reported to their professional body and, where possible, be prosecuted. Moreover, any vet who has previously been found guilty of fraudulent behaviour should not subsequently be engaged by the Department.

The Department did not implement PAC’s recommendation to increase in-house staff levels

39. In 1994, the Westminster PAC recommended that the Department increase the number of its in-house ‘temporary veterinary officers’, because they were less costly than PVPs. Despite this, in-house veterinary staff numbers actually fell, from 32 in 1996 to 12 in 2003, with the result that an even greater level of bovine TB testing was transferred to PVPs. Using the Department’s own costings, the Audit Office calculated that, over the 10-year period to March 2006, the transfer of in-house testing to PVPs cost the Department an additional £2.7 million. The Department commented that the fall in staff numbers was not so much a conscious reduction in the bovine TB programme as a need to divert resources to combat BSE and Brucellosis, which were also rising in the mid-to-late 1990s.

40. This explanation is far from convincing. In the Committee’s opinion, allowing the numbers of in-house TB testing staff to drop so dramatically was ill-considered. As well as the additional cost involved, the reduction in staff numbers coincided with the period during which bovine TB levels increased to the highest in Europe. Bearing in mind also, the Department’s concerns at that time about the quality of some PVP testing, the Committee must conclude that the Department’s actions were ill-considered.

41. The Department pointed out that the number of in-house veterinary staff increased between 2004 and 2006 and that, at present, there are 27 vets in post on the bovine TB programme. While this is a considerable improvement on the 2003 position, the Committee notes that this is still below the 1996 level of 32 and also the complement of 30 recommended in the Department’s 2002 Policy Review.

42. The Department also said that it has looked again at comparative costs and believes that the difference is now much reduced - £3.53 for a PVP test, compared with £3.20 in-house. This is a marked change from the 2003 position, when it calculated costs of £3.26 for PVPs and £1.99 in-house. It is not clear to the Committee whether this indicates that the Department’s own costs have dramatically increased (while those of PVPs have risen only slightly), or its 2003 figures were erroneously stated. Either way, it is a matter of concern.

Recommendation 9

43. Given the high level of testing in the bovine TB programme, even a relatively small difference in the unit cost of tests can have a significant impact on overall programme expenditure. The Committee recommends that the Department closely monitors the relative costs of in-house and PVP testing on an ongoing basis, to ensure that best value for taxpayers’ money is consistently achieved.

The use of Lay Testers could provide an additional resource to combat bovine TB at less cost

44. In England, the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) is looking at the scope for using lay testers to conduct bovine TB tests on non-export animals. It is currently in negotiations with the European Commission (who would have to approve the change) and is undertaking a trial to test the viability of the approach. The Committee notes the Department’s comments that the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons is reluctant to agree an approach where its members would have to complete a test, the first part of which they had not carried out.

Recommendation 10

45. The use of lay testers has the potential to provide a useful new resource, while achieving substantial cost savings over current arrangements. The Committee recommends that the Department reviews the outcome of the DEFRA trial and its discussions with the European Commission. If DEFRA is successful in obtaining approval to lay testing, the Committee recommends that the Department gives full consideration to adopting a similar approach in Northern Ireland.

The Department should consider increasing the percentage of routine herd tests carried out in-house

46. Under its contract with PVPs, the Department can opt to undertake up to 10 per cent of routine bovine TB tests in-house. However, for many years, the actual level has been much lower than this. The Department said that the level of in-house routine testing has now risen, from 1 per cent in 2005 to 2.5 per cent in 2008. It also said that, overall, the Department currently undertakes about 22 per cent of all testing, most of which involves high risk testing (“at risk" and “restricted" tests).

47. The Committee asked whether, in view of the Department’s analysis that in-house staff are significantly more likely than PVPs to detect bovine TB, it would be better to redeploy some of the Department’s resources to undertake a greater level of routine tests. The Department responded that it is “traditional" for Departmental staff to perform the high risk testing, where infection is likely to be revealed. The Committee wonders, however, whether the consequent reduction in likelihood of disease being detected during routine testing might result in greater overall levels of infection - failure to detect disease at a routine test means that an infected animal has freedom to move, both within and beyond its existing herd, over the following 12 to 15 months.

Recommendation 11

48. The Committee recommends that the Department reconsider the current allocation of testing between PVPs and in-house staff, with a view to increasing the proportion of routine tests conducted in-house. This would also provide a better benchmark for the quality review of PVP routine testing, about which the Department has previously expressed concerns.

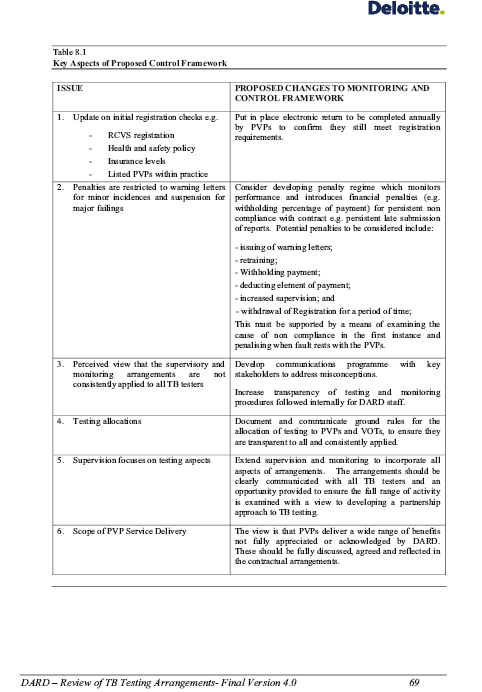

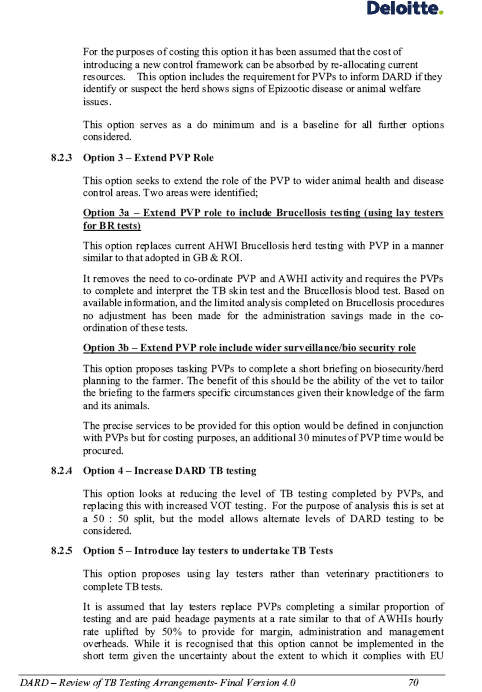

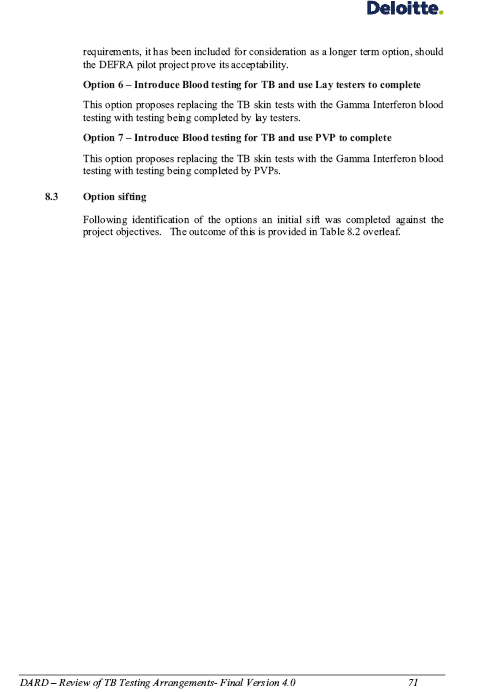

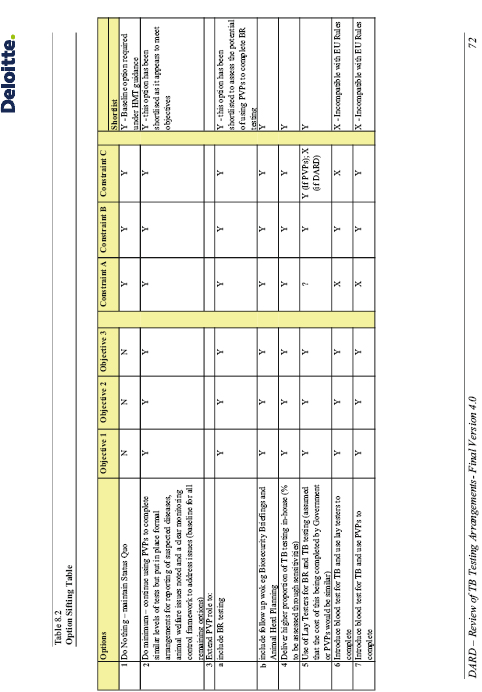

The Department was slow to progress its 2006 Review of bovine TB testing arrangements

49. The Department’s ‘Review of bovine TB testing arrangements’ has made slow progress. The review was recommended in 2002, yet it took until 2005 to engage consultants. The consultants reported in 2006, recommending a range of improvements to testing arrangements but, as yet, these have not been implemented. The Department explained that it met with the AVSPNI in 2007 to discuss the recommendations and had subsequently received detailed comments from that body. Matters had not progressed further because the Department had decided to wait for the Audit Office report and this Committee’s comments. Overall, however, it does not think that a great deal of time has been lost.

50. The Committee disagrees. Seven years have now elapsed since the Department’s Policy Review recommended a review of testing arrangements and two and a half years have passed since the Department’s consultants reported. Yet matters have still not been finalised. Given the importance of the review to the conduct of the bovine TB programme, this is indefensible. In the Committee’s opinion, the Department needs to demonstrate a stronger sense of purpose.

Recommendation 12

51. The Committee recommends that, as a general principle, Departments should never delay taking action on what should be urgent issues, pending completion of an Audit Office report. In this particular case, the length of time the Department is taking to put the findings of its review of testing arrangements into practice is unacceptable. It must finalise its position on each of the issues involved and begin implementation as soon as possible.

The Blood Test:

The Department was slow to introduce the “blood test" as an ancillary test

52. The gamma interferon blood test is an ancillary test that may be used to complement the skin test. The Department had been considering using the test in restricted herds since 1996. Following the 2002 Policy Review, it carried out a number of trials from 2004 to 2006. In June 2007, its use as a supplementary to the skin test, on a voluntary basis, was confirmed as part of the Department’s bovine TB control programme.

53. The Committee asked why the Department had taken so long to reach a decision on the test. The Accounting Officer said that there were two main reasons – first, it was not approved by the EU as a supplementary test until 2002 and, second, there were logistical problems in getting blood samples to the laboratory within one day of the sample being taken.

54. While the Committee welcomes the use of the blood test as a worthwhile addition to the eradication control programme, the evidence suggests that it could have been introduced earlier. In England and Wales, blood test trials began in 2002 and were fully rolled out in 2006, while in the Republic of Ireland blood tests were introduced in problem herds in 2005.

There is scope for more extensive use of the “blood test" in high risk herds

55. Because the blood test has a greater sensitivity than the skin test, it is particularly suitable for use in high risk herds. However, with use of the test being voluntary, not all farmers take up the offer. The Department said that uptake was some 80 per cent, but added that where the test produced positive results, only 70 per cent of farmers agreed to slaughter the animals. The likelihood, therefore, is that substantial numbers of infected animals are being retained within herds.

56. The Committee found this disturbing and suggested that a compulsory scheme may be warranted. The Department said that it is looking at this issue but explained that there are two factors to consider. The specificity of the blood test is not yet as good as the skin test and so it will also identify, as reactors, a number of animals that are not actually infected. Secondly, the blood test currently costs £20 compared with the skin test at £2.50.

57. The Committee notes the Department’s comments. Notwithstanding the lower specificity of the blood test, its greater sensitivity over the skin test does appear to offer a useful option in dealing with problem herds. And while the blood test is more expensive, it could prove to be a sound overall investment if disease levels were radically reduced.

Recommendation 13

58. It appears to the Committee that there is a strong case for introducing compulsory blood tests in problem and high risk herds. In view of the cost implications, the Committee recommends that the Department considers conducting a trial, in a high incidence area, as a basis for a cost-benefit assessment. Given the need for more research into the efficacy of the blood test, the Committee urges the Department to ensure that sufficient resources are applied to ensure that this work receives a high priority.

Preventing the Spread

of Bovine Tuberculosis

59. Sound biosecurity measures are essential to combat the spread of infection. The nature of farming in Northern Ireland, with small fragmented farms, strong dependence on rented pasture and a high level of movement between and within herds, facilitates the spread of bovine TB. Departmental analyses in 1996 and 2002 showed that the three main sources of bovine TB infection were from neighbouring herds (30 per cent), purchased cattle (23 per cent) and wildlife (rising from 9 to 16 per cent).

Most boundary fencing is inadequate

60. The Department’s 2002 Policy Review highlighted that inadequate boundary fencing (including stone walls and hedging) has been a major impediment to the successful control and eradication of bovine TB and noted that 79 per cent of fencing here did not prevent nose-to-nose contact between herds. The Committee asked for an up-to-date figure for the level of nose-proof fencing but was disappointed to learn that the Department did not know. The Accounting Officer said that, overall, there were 800,000 fields in Northern Ireland, with over 180 million metres of fences, hedgerows and stone walls, much of which form the external boundaries of farms. In view of the likely cost involved, he did not think a survey was worth carrying out. However, he did mention that under the Department’s countryside management schemes, grants are provided to improve some 600,000 metres of fencing each year. The Committee notes that this comprises only 0.3 per cent of the total annually.

61. Since 2004, herd keepers have been statutorily required to maintain fencing that prevents contact with adjoining herds. The Department’s 2004 ‘Biosecurity Code’ specifies double-fencing with at least a 3-metre gap. Given the generally poor overall standard of boundary fencing, the Committee was surprised to learn that there have not been any prosecutions by the Department specifically for non-compliance. The Department said that new legislation, due later this year, will contain new statutory biosecurity codes which, ultimately, it wants to link to compensation payments so that poor biosecurity will lead to a reduced level of compensation. It also said that it will be carrying out a study involving 350 farms in a high-incidence area of bovine TB in County Down. This will specifically focus on epidemiological and biosecurity factors and include an examination of the role that boundary fencing plays.

Recommendation 14

62. Given that poor boundary fencing appears to have played a significant role in the spread of bovine TB, the Committee is disappointed that the Department does not have a firm grip on this issue. In the Committee’s view, there is merit in obtaining a clear view of the real extent of the problem and the Department needs to consider how this can be tackled. As regards the enforcement of fencing requirements, the Committee recommends that the Department acts on its intention to link non-compliance with biosecurity codes to the level of compensation awarded and expects this to be taken forward as a priority issue.

Participation levels in the Life-long Learning Programme have been very low

63. The Department’s 2002 Policy Review recommended introducing a life-long learning programme for farmers, to include early disease recognition and development of farm biosecurity plans. By December 2008, only 1,134 herd keepers out of 25,000 had taken the course. The Department told the Committee that it never intended that all farmers would attend this training. Instead, the focus is on farmers who are developing their businesses – the target for next year is to involve a further 90 farmers. This appears to the Committee to be a disappointingly low figure. The Department also said that, although it had not formally evaluated the programme, feedback from participants was that the training was worthwhile and “eye opening".

Recommendation 15

64. The Committee considers that the Department should be much more proactive in encouraging farmers to attend training on early disease recognition and farm biosecurity planning and would like to see the number of participants substantially increased. The Committee recommends that the Department makes attendance compulsory for farmers whose herds have suffered repeated infection. Failure to attend should result in a reduction of compensation in future outbreaks.

The risk of purchased infection has not been fully addressed

65. Departmental analyses in 1996 and 2002 indicated that almost one quarter (23 per cent) of bovine TB breakdowns were caused by purchasing infected animals. In 1995, the Department considered introducing pre-movement testing for herds which had a recent bovine TB history but considered that the benefits did not justify the costs involved. In 2000, and again in 2004, the EU recommended compulsory pre-movement testing of cattle. The Department’s 2002 Policy Review also considered it “worth doing", estimating savings of £500,000 a year to the public purse.

66. The Committee asked why, against this background, the Department had repeatedly decided against pre-movement testing. The Department said that pre-movement testing was carried out on animals being exported to Great Britain and Europe but it had decided against pre-testing for movement within Northern Ireland for two main reasons. The £500,000 savings estimated by the 2002 Policy Review was based on farmers paying two-thirds of the cost of the test. Farmers representatives had objected vehemently and the Department thought, therefore, that delivery was probably impractical. Secondly, it considered that, as there is already an Annual Herd Test in Northern Ireland, further testing was not appropriate. The Department pointed out that, in more recent analyses, the level of purchased infection had dropped to 11 per cent. However, as the figure for “unknown" transmission routes has more than doubled, to 36 per cent, the Committee takes little comfort from this.

67. In the Committee’s view, there remains a strong case for pre-movement testing on a wider scale than at present. The shortcomings of the skin test in detecting disease means that there is still a significant risk of purchasing infection, even from herds classified as “officially tuberculosis free". The Committee also believes that the Department should not rule out some form of cost-sharing with the farming industry as a future option. Hastening the eradication of bovine TB is very much in the industry’s interests also.

Recommendation 16

68. The Committee recommends that the Department considers introducing pre-movement testing, for animals moving within Northern Ireland, perhaps on a trial basis within a high incidence area. As part of the Department’s consideration, an updated cost-benefit analysis should be prepared. This would also provide a useful basis for opening dialogue with farmers’ representatives on cost sharing.

The Department has been slow to respond to the wildlife factor

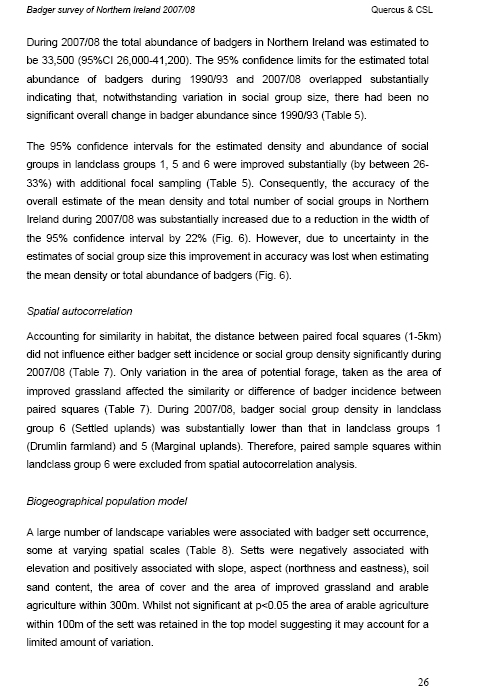

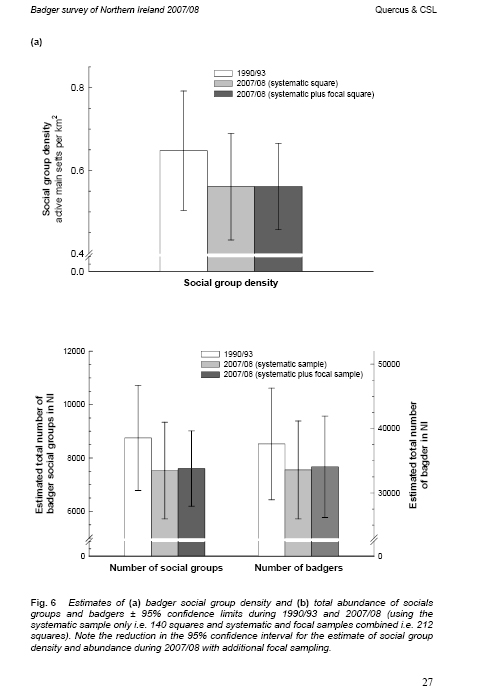

69. A reservoir of infection in wildlife, particularly badgers, has long been thought to be a factor in bovine TB transmission. The Department attributes around 16-17 per cent of outbreaks in recent years to wildlife. While the scientific evidence is complex and at times contradictory, long-term badger-culling trials in both Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland suggest that culling of badgers is not a cost-effective solution to the bovine TB problem and, in certain circumstances, may even increase the spread of the disease.

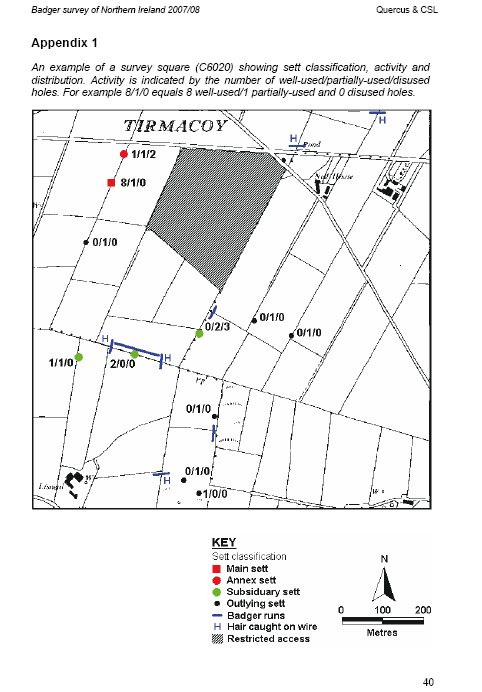

70. To date the Department has not actually intervened to tackle the wildlife factor in Northern Ireland, although it set up a Badger Stakeholder Group in 2004 and commissioned a badger population survey in 2008. The Department said that its next step is to carry out a badger prevalence survey. Based on a test of 1,000 badgers, it will analyse the correlation between the strain of bovine TB infection in the badger population and cattle infection. This will form the basis for deciding on whether, for example, a pilot cull would be justified. The Department also said that a widely held view on the best way forward is to develop a vaccine for badgers. DEFRA has recently announced a 5-year vaccine trial, beginning in 2010, with the aim of developing an oral vaccine by 2014. The Accounting Officer pointed out that, in Northern Ireland, a pilot cull would cost £1 million a year and a vaccine trial over £1 million each year.

71. It seems to the Committee that the Department has been extremely slow to take action on the wildlife issue, given the scale and longevity of the problem. Had the Department initiated the Northern Ireland badger population and prevalence surveys at an earlier stage, it would now have been in a position to take action. The Committee is also concerned about the timescale for future progress and is not wholly confident that the Department is committed to moving this issue forward as quickly as the Committee would like.

Recommendation 17

72. It is important that the wildlife factor in the transmission of bovine TB is addressed. The Committee recognises that this is an emotive issue which has not been objectively answered. When the badger prevalence survey is completed and the way forward determined, the Committee expects real progress to be made with a minimum of delay.

Use of a “test-bed" approach may help in tackling bovine TB

73. The impression gained by the Committee, both from the C&AG’s report and the Department’s evidence, is that there has often been a reluctance within the Department to take decisive action that would lead to the eradication of bovine TB, rather than merely containing the disease. It seems to the Committee that there is a need to develop a specific combination of measures that, used in concert, effectively eradicate the disease. Given the limit on the Department’s resources, this might best be developed and tested within a designated geographical area, where incidence of the disease is acute. In the Committee’s view, this type of “test-bed" approach could be used to build a comprehensive cost-benefit model of the most efficient eradication strategy, which could then be progressively rolled out to other districts.

Recommendation 18

74. The Committee recommends that the Department examines the potential for adopting a “test-bed" approach as a means of determining the most cost-efficient combination of measures to eradicate bovine TB.

A conflict of interest has been alleged in the Department’s letting of the badger survey contract

75. Serious concerns have been raised with the Department in relation to alleged conflicts of interest in the award of the contract to carry out the badger population survey. The Department has been carrying out an internal review of the case and has undertaken to pass a copy of the findings to the Committee when the review has been completed. The Committee notes that the Comptroller and Auditor General has been monitoring the case.

EU Matters

76. The EU Directive sets out bovine TB minimum control measures for each Member state. Compliance is required in order to avoid restrictions on trade and to qualify for additional funding to combat the disease. For many years, the Department was not compliant with the Directive on a range of matters. While the position has now improved, the Department is not yet fully compliant.

There is an inherent conflict of interest in PVPs testing their clients’ herds for bovine TB

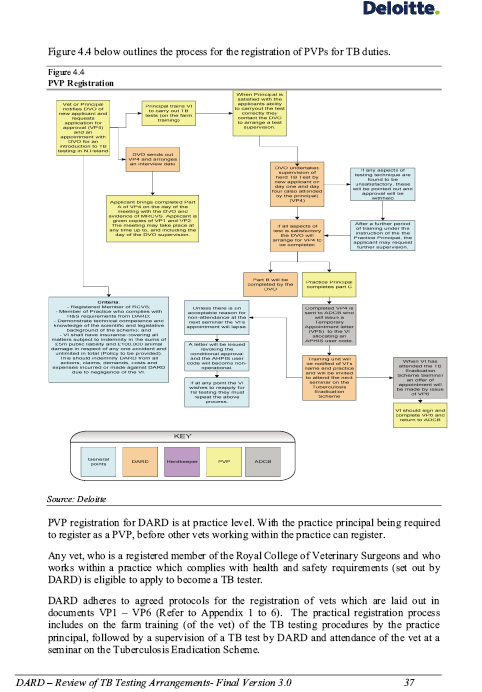

77. The EU Directive requires that a private veterinary practitioner should not test a herd in which he or she has a financial interest. However, the practice in Northern Ireland is that PVPs often conduct bovine TB testing on their own clients’ cattle. The Department said that its legal advice is that private vets should not test the herd of a close family member. Therefore, it has not regarded the practice here as a conflict of interest. It also pointed out that, in the UK and the Republic of Ireland, the practice is the same.

78. The Department’s 2006 ‘Review of bovine TB testing arrangements’, recommended that PVPs should test herds other than their clients’ herds, in the same geographical area, on a rotational basis. The Committee notes the Department’s comments that the AVSPNI is opposed to this, on the basis that PVPs have a detailed knowledge of their own herds, which it sees as important for any subsequent epidemiological investigation. AVSPNI also believes that the change would be less efficient, more costly and lead to an increase in the backlog of tests. The Committee notes that the Department has not yet finalised its thinking on this matter.

79. In the Committee’s view, PVPs do have a financial interest in their clients’ herds – not necessarily as owners or close relatives but through their normal veterinary business relationship with clients. By also conducting bovine TB tests for the Department, on clients’ herds, an inherent conflict of interest exists. The Committee recognises, however, that this is a difficult issue and that changes to the current approach may create difficulties.

Recommendation 19

80. It is important that the Department finalises its thinking on how best to address the conflict of interest inherent in PVPs carrying out testing in their clients’ herds. If the conflict cannot be eliminated, the Committee recommends that the Department ensures that the risks are properly managed and that adequate safeguards are put in place. This should include an effective system of monitoring the work of PVPs, supplemented by a programme of robust supervisory checks.

Annual Herd Tests are not always carried out within the 12-month deadline

81. Under current control procedures, all cattle herds in Northern Ireland have to undergo an Annual Herd Test for bovine TB. However, the Department has not succeeded in ensuring that all herds meet the 12-month deadline. Compliance has improved considerably in recent years, moving from a position in 2001 when more than a quarter of all herds (over 6,000) missed the deadline, to a level of 95 per cent compliance in 2008 (when 1,250 herds were overdue). While this is a marked improvement, the fact remains that the annual herd test is the Department’s primary control measure and, as such, the Committee expects much closer to 100 per cent compliance.

82. There are also considerable numbers of individual animals that have missed their annual bovine TB test, by substantial periods of time. This can be due to, for example, animals moving between herds and missing the annual herd test in each. Again the position has improved in recent years, falling from 13,000 animals in 2005 to 6,000 in 2008. However, as with herd tests, there is more to be done. The Department pointed out that there is no specific reference to individual animal tests in the EU Directive, the inference being that failing to test individual animals within the 12-month deadline does not constitute non-compliance. In the Committee’s opinion, it would be absurd not to extend the annual testing requirement to include individual animals also.

83. The Department pointed out that it introduced a change in 2008 whereby any individual animal that has not been tested within the previous 15 months has its movement restricted until the test is carried out. Again, this is an improvement, but it still permits the movement of animals that are up to three months overdue their test. As such, it offers a lower level of control than the 12 months deadline laid down in the EU Directive. In the Committee’s opinion, movement of individual animals out of a herd should be restricted where they have not been tested within the previous 12 months.

Recommendation 20

84. The Committee welcomes the reduction in numbers of overdue herd and individual animal tests in recent years. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement and the Committee recommends that the Department aims to achieve much closer to 100 per cent compliance with the 12-month deadline, for all animals.

The isolation of reactors and inconclusives remains a widespread problem

85. In 2004, EU inspectors found that there were problems on farms with the isolation of animals that were found to be “reactors" or “inconclusives", following TB testing. They also reported that the Department’s instructions on isolation were not clear. The Department told the Committee that this is still a difficult problem in a number of herds, with farmers facing major logistical difficulties in isolating animals, particularly in dairy herds or where animals are in housing.

86. The Department said that one approach to the problem has been to reduce the time taken between getting positive test results and removing animals from the farm. It explained that the EU target is 30 days, which it now achieves in 97 per cent of cases. In order to move reactors off farms more quickly, the Department itself imposed a 15-day removal target, which it is meeting in around 70-80 per cent of cases.

87. The Committee welcomes the improvements in reactor removal time achieved by the Department. However, it is worrying that the isolation of reactors and inconclusives on farms remains a substantial problem. It is incumbent upon the industry to meet the requirements of the EU Directive and the Committee finds it most unsatisfactory that there are farms not properly equipped to apply the standard control procedures.

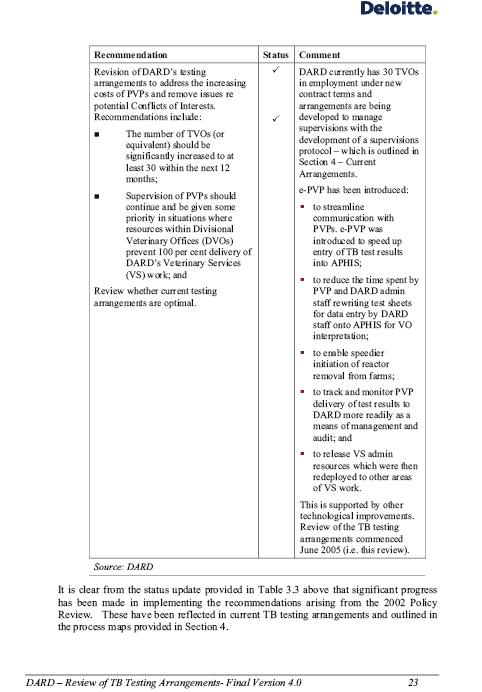

Recommendation 21