Session 2008/2009

Eighth Report

Public Accounts Committee

Report on Brangam, Bagnall & Co:

Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated

Against the Health and Personal

Social Services

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the committee

relating to the report and the minutes of evidence

Ordered by The Public Accounts Committee to be printed 5 February 2009

Report: 26/08/09R (Public Accounts Committee)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts and reports of the Comptroller and Auditor General laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 51 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Paul Maskey*** (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns**

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr Jim Wells*

Mr John Dallat

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr George Robinson****

Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr Jim Shannon*****

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke on 1 October 2007

* Mr Ian McCrea replaced Mr Mickey Brady on 21 January 2008

* Mr Jim Wells replaced Mr Ian McCrea on 26 May 2008

** Mr Thomas Burns replaced Mr Patsy McGlone on 4 March 2008

*** Mr Paul Maskey replaced Mr John O’Dowd on 20 May 2008

**** Mr George Robinson replaced Mr Simon Hamilton on 15 September 2008

***** Mr Jim Shannon replaced Mr David Hilditch on 15 September 2008

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report

Report

Frauds perpetrated by George Brangam and why they were not picked up earlier

Adequacy of the Department’s investigation

Concerns over the conduct and probity of George Brangam

prior to setting up Brangam Bagnall & Co

Regulatory regime for the legal profession

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

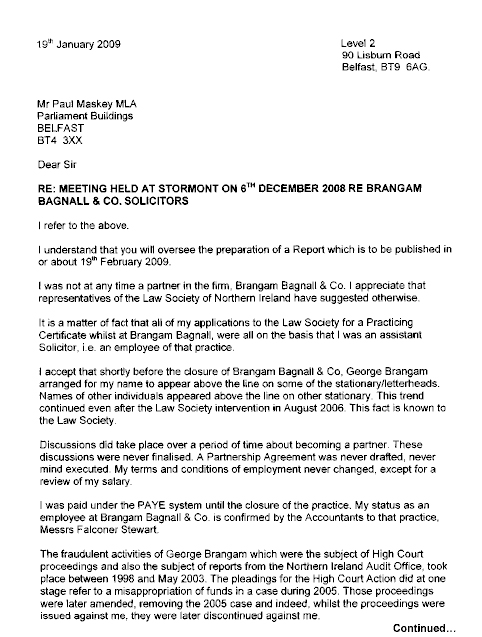

Correspondence of 19 January 2009 from Mr Gary Daly

Appendix 4:

List of Abbreviations

Used in the Report

The Agency Central Services Agency

BB & Co Brangam, Bagnall & Co

Causeway Trust Causeway Health and Social Services Trust

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General

CPD Central Procurement Directorate

The Department Department of Health, Social Services & Public Safety

DFP Department of Finance & Personnel

HANI Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland

HSC Health and Social Care

HPSS Health & Personal Social Services

HSS Health & Social Services

LEDU Local Enterprise Development Unit

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

Law Society The Law Society of Northern Ireland

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. Following concerns raised by Causeway Health & Social Services Trust (Causeway Trust) in August 2006, The Law Society of Northern Ireland (Law Society) investigated potential irregularities at the practice of Brangam, Bagnall & Co (BB & Co), which led to the practice being closed down on 1 September 2006. Over a period of seven years, George Brangam, solicitor and owner of the legal practice of BB & Co was found to have fraudulently extracted at least £278,000 from six of the eleven health bodies to whom his practice provided legal services. The Department of Health, Social Services & Public Safety (the Department) has subsequently taken legal action and recovered this sum in full.

2. This is one of the largest and most worrying cases of multiple frauds to have hit the Northern Ireland public service in many years. The case is particularly galling for three reasons. First, almost all of these frauds could easily have been prevented. Second, almost all of these frauds could have been detected at a much earlier stage, if some very basic checks and controls had been working effectively. Third, although George Brangam was a private sector contractor when he carried out the frauds, he previously held a senior managerial position of trust in the health service. He therefore had inside knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of the controls system. This enabled him to target his fraudulent activity with maximum precision and minimum risk of detection.

3. This is yet another example of a senior person involved in public services abusing their position of trust. As a result of this and other cases such as the Northern Ireland Events Company and the Emerging Business Trust, the Public Accounts Committee is left with the impression that the public service in Northern Ireland has been more vulnerable to abuse by unscrupulous individuals than it should have been. This must no longer be tolerated.

Frauds perpetrated by George Brangam and why they were not picked up earlier

4. One of the key lessons from this case is that the majority of frauds carried out by Brangam could have been prevented if cheques in settlement of clinical negligence and other cases had been paid directly to claimants rather than through BB & Co. The Department has now introduced new procedures which do not permit cheques in settlement of legal cases to be channelled through solicitors, when there is no sensible business case for doing so.

5. Once the frauds had been committed, almost all of them should have been detected quickly through the application of basic checks. For example, the Comptroller & Auditor General’s (C&AG’s) report refers to a case where Brangam received payments twice to settle the same case. If the health body concerned had sought evidence of the actual settlement or obtained acknowledgement from the claimant that the payment had actually been received, this fraud would have been detected immediately.

6. The Committee wishes to send out a strong message that it is wholly unacceptable to dispense with basic payment checks when working with claims submitted by professionals. This point is particularly relevant to the health service, where historically, claims submitted by professionals, i.e. solicitors, doctors, pharmacists, opticians and dentists, seem to have been subject to a much lower level of scrutiny than claims from other contractors. This issue was examined by the Committee’s Westminster predecessor in 1999. [1] The Department has assured the Committee that this culture has changed. The Accounting Officer told the Committee that it now has stringent controls and a zero tolerance attitude. Payments to someone who is well known, is a colleague, or has been one, will now only be made if there is sufficient evidence to support them.

7. The Committee commends the junior member of staff in Causeway Trust who, alert to the possibility of fraud, raised concerns with senior management which led to Brangam being caught. It is disappointing that earlier opportunities for identifying these frauds were missed because senior management did not act decisively and promptly when concerns were raised.

8. Although the frauds were eventually picked up by health service staff they should also have been capable of detection through the Law Society’s regulatory regime. This is because Brangam repeatedly broke solicitors’ regulations when committing the frauds. However, in the event, these frauds were not detected by the Law Society. It has attributed this to the sophisticated paper trail Brangam used to cover his tracks; the sheer volume of health bodies’ transactions that went through the practice’s accounts; and the sampling approach used by its internal accountants, who carry out inspections on its behalf. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Law Society has also learnt lessons from this fraud in terms of its own oversight of client accounts and this has been shared with its accountants.

Adequacy of the Department’s investigation

9. The Committee is not satisfied that the Department’s investigative work was sufficiently timely, wide-ranging or penetrative. The Department told the Committee it was confident it had identified the full extent of the frauds and that subsequent to the initial forensic investigation and the C&AG’s report, it had carried out further work which supported this view. However, the Committee considers that in the forensic investigation, much more effort should have been made to reconstruct the incomplete record trail from third party sources, such as claimants’ solicitors and Court Service records. The Department’s investigative work should also have included formal assessments of the possibility of collusion between Brangam and public officials, and whether, and to what extent, there had been any supervisory negligence.

Concerns over the conduct and probity of George Brangam prior to setting up

Brangam Bagnall & Co

10. During the 11 years Brangam provided legal services to the health service he was effectively treated as a very low risk contractor. Payments by a number of health bodies to BB & Co were subject to a level of scrutiny which fell far below minimum acceptable standards. Yet by the time he left Central Services Agency (the Agency) to set up his own business there was already a sufficient body of concern about his behaviour, conduct and character to justify an enhanced level of scrutiny. The Committee finds it astonishing that the Agency’s concerns were not shared with its parent Department at the time. Again, the Committee would like to reiterate a point made in the Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland Report [2] that, in situations where it is in the public interest to protect standards in public life and the public purse, there should be a mechanism for information sharing. Had such a mechanism been in place those health bodies who had entered into contracts with BB & Co may have subjected their payments to this practice to a higher level of scrutiny and picked the fraud up earlier.

11. The Committee is also appalled at the way in which Brangam’s departure from the Agency was handled. For the six-month period between expressing his intention to leave and actually leaving, Brangam was involved in two conflicting roles. On one hand, he was running the in-house legal services function as the Director of Legal Services, and on the other he was establishing his own practice to provide legal services to the health sector. The attempt to manage this conflict and the leadership shown by both the Department and the Agency at this time was woefully inadequate.

Procurement of legal services

12. This is one of the worst examples of bad procurement practice that this Committee has ever seen. It is unbelievable that the Select List for legal services lasted for 12 years, preventing other firms from entering this market. However, the fact that BB & Co received 70% of the work put out to the private sector market over 10 years is astounding. The lack of clear direction has resulted in an open market not developing for legal services and doubts over whether value for money was ever achieved during this period. Furthermore, the Committee considers that the ineffective management of this procurement process helped create the favourable conditions that allowed Brangam to perpetrate these frauds against the health service. It is the Committee’s view that the Department failed to ensure that the provision of legal services to the health sector was undertaken within a properly regulated framework, for an unacceptably long period of time.

13. The Committee cannot understand why subsequent procurement exercises had to be abandoned considering the wealth of expertise and experience available. There is every possibility that the excessive duration of this Select List was also a factor in the perpetration of the frauds by Brangam. Controls in the area of procurement must be strengthened to prevent such a debacle from occurring again.

Regulatory regime for the legal profession

14. The Committee called on the Law Society to provide evidence in a supplementary session and found this to be very helpful in enhancing their understanding of its regulatory role. The Committee is surprised at the number of interventions by the Law Society in solicitor practices and the level of fraud within such a small society as Northern Ireland and notes there are similar problems in other jurisdictions. The Committee understands that the regulation of legal services in Northern Ireland is currently under consideration and would welcome a comprehensive update from DFP on progress in this area.

Summary of Recommendations

Frauds perpetrated by George Brangam and why they were not picked up earlier

1. The Committee recommends that the Department monitors the performance of other firms providing legal services to the health sector, to ensure they are complying with guidance issued since the frauds were discovered (see paragraph 9).

2. The Committee considers it wholly unacceptable to dispense with basic payment checks and rely exclusively on the honesty and integrity of professionals when dealing with public services. The Committee expects departments and their sponsored bodies to apply the same rigorous standards to ensure a payment is regular, regardless of whom they are dealing with (see paragraph 11).

3. The Department has now introduced new procedures which do not permit cheques in settlement of legal cases to be channelled through solicitors, when there is no sensible business case for doing so. The Committee recommends that the Department carries out regular checks to ensure these new procedures are strictly applied. The Committee also calls on the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) to ensure that similar procedures are rolled out across the entire public sector (see paragraph 13).

4. The Department must ensure that appropriate mechanisms are in place to provide assurance that financial procedures in respect of legal and other claims are being followed across the Health and Social Care sector. Accounting Officers need to satisfy themselves that internal audit service providers have built this area into their programme of work to ensure controls and compliance with them is tested periodically. Furthermore, internal audit should pay particular attention to instances where senior management override occurs to ensure that such action is legitimate (see paragraph 16).

5. The Committee recommends that training needs and leadership in the area of contract claims is reviewed within the health sector and rolled out as a matter of urgency. The Department should also consider the extent of the fraud awareness training currently delivered within the health sector (see paragraph 20).

6. The Committee wants assurance that the slipshod, unprofessional practices in this case do not apply elsewhere and recommends that internal audit, throughout the health sector, gives sufficient weight to the audit of contracts. The Committee also calls upon the C&AG to pay particular attention to such contracts as part of NIAO’s routine financial audit work (see paragraph 22).

Adequacy of the Department’s investigation

7. Procurement processes in the public sector often take many months to complete. The Committee recommends that all Departments review their contingency arrangements to ensure they have:

a) an up to date Fraud Response Plan in order to minimise the time required to think through the scope and nature of any investigation once a fraud is notified; and

b) appropriate standby measures in place to allow them to get forensic investigations up and running quickly (see paragraph 25).

8. The Committee is very concerned about the apparent inadequacy of health bodies’ records management systems if records have now appeared that were previously considered to be legitimately destroyed, and recommends that the Department provides a fuller explanation (see paragraph 31).

9. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Department is reviewing its records management guidance and recommends that the findings of this Report, and DFP’s response to the Hospitality Association in Northern Ireland Report are considered when drafting it. New guidance issued must be both understandable and comprehensive (see paragraph 32).

10. The possibility of collusion should never be ruled out prematurely and always be carefully explored in the terms of reference for any fraud investigation. When major contract fraud occurs, the Committee expects that investigations would automatically cover hospitality registers and registers of interest. The Committee requires the Department to report back on details of any gifts or hospitality offered by Brangam to health bodies receiving services, and details of any interests registered by health service staff in connection with BB & Co (see paragraph 38).

11. The Committee recommends that terms of reference for forensic investigations should be pitched sufficiently widely to identify the full extent of the fraud and the possibility of supervisory negligence. DFP should also ensure that departmental guidance on fraud investigations includes consideration of supervisory negligence as a matter of course. The Committee expects in cases of major fraud that departments should consult with NIAO to adequately scope their terms of reference (see paragraph 40).

Concerns over the conduct and probity of George Brangam prior to setting up

Brangam Bagnall & Co

12. Although the Committee welcomes the recovery of both amounts defrauded and costs of £123,000, it is not satisfied that all options for recovery were fully explored in this case. The Committee recommends that when fraud occurs Departments should use all means at their disposal to maximise the recovery of public funds (see paragraph 44).

13. The Committee reiterates a recommendation made in its Report on the Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland (HANI) that, in situations where it is in the public interest to protect standards in public life and the public purse, there should be a mechanism for information sharing (see paragraph 45).

14. This is another example of a case where the public sector has tried to manage a conflict of interest that should have been avoided. The Committee recommends that conflicts of interest must be identified at an early stage. Departments need to better assess the risks involved in trying to manage a conflict if they choose to do so and then address the conflict immediately and effectively. Once again DFP is called upon to give clearer guidance on the types of situation, where conflicts should be avoided, rather than managed (see paragraph 50).

Procurement of legal services

15. When procurement arrangements are being put in place they should always be designed in a way which provides regular opportunities for new suppliers to enter the market. In the Committee’s view, where a list of approved providers is used, departments should regularly monitor the allocation of work to firms to assess if an open market has, in fact, developed. Where the market does not grow as expected, departments should take prompt action to prevent a monopoly situation from arising, a firm becoming over stretched, or over dependency on one provider. The Committee recommends that DFP ensures appropriate guidance is issued to all departments (see paragraph 53).

16. The Committee is seeking assurances from the Department that there will be no further cases of competitions being abandoned due to its inability to assess and compare bids (see paragraph 56).

17. The Committee’s view is that evaluation criteria should be absolutely clear at the start of a procurement process. Furthermore, relevant and accurate data must be provided to tenderers to enable them to assess the services they will be required to provide, and to submit their bids. The Committee recommends that DFP consider this recommendation within the context of its existing procurement guidance (see paragraph 57).

18. The Committee is concerned that the Department has failed to fulfil assurances previously given. It expects departments to respond quickly and appropriately to address all assurances provided to the Committee through regular monitoring of progress (see paragraph 59).

19. The Committee recommends that, in cases like this, where allegations of fraud or other impropriety exist, public bodies should consider suspending financial dealings with those directly, and indirectly, involved until the main investigation has been completed (see paragraph 62).

Regulatory regime for the legal profession

20. The Committee would welcome details of what action, if any, has been taken by DFP following the recommendations of the Legal Services Review Group (see paragraph 71).

21. The Committee recommends that where legal services are provided by private sector firms, public bodies should ensure they have the right of access to inspect their own case files, as and when desired. These rights should be exercised from time to time (see paragraph 74).

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee (the Committee) met on 4 December 2008 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s (C&AG’s) report: Brangam, Bagnall & Co: Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated against the Health & Personal Social Services (HPSS) and a supplementary memorandum on Contracting for Legal Services in the health sector (NIA 195/07-08, Session 2007-08). The witnesses were:

- Dr Andrew McCormick, Accounting Officer, the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (the Department);

- Mrs Julie Thompson, Acting Senior Finance Director, Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety;

- Mr Dean Sullivan, Director of Planning and Performance, Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety;

- Mr Donald Eakin, Senior Vice-President, The Law Society of Northern Ireland;

- Mr James Cooper, former Senior Vice-President, The Law Society of Northern Ireland;

- Mr Kieran Donnelly, Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General; and

- Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts, Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP).

2. In August 2006, Causeway Health & Social Services Trust (Causeway Trust) raised concerns with The Law Society of Northern Ireland (Law Society), regarding potential irregularities involving the practice of Brangam, Bagnall & Co (BB & Co). The Law Society investigated matters at the practice and froze George Brangam’s assets after identifying a number of anomalies and irregularities within the client accounts. The practice was closed down by the Law Society on 1 September 2006. In April 2007, the Department’s forensic accountants issued their report identifying the fraudulent extraction of £278,000 from six of the eleven health bodies to whom legal services were provided. Following Brangam’s death in August 2007, criminal proceedings against him could not continue. The Department has since taken successful civil action to recover this money.

3. The C&AG’s report examined the events leading to the discovery of these frauds, the extensive nature of the frauds committed and action taken since they were uncovered. The C&AG also conducted a supplementary investigation into the procurement of legal services. The resulting memorandum provided background on how and when Brangam became a provider of legal services to health bodies. The Committee also took evidence from the Law Society.

4. In taking evidence, the Committee focused on the following issues:

- frauds perpetrated by George Brangam and why they were not picked up earlier;

- adequacy of the Department’s investigation;

- concerns over the conduct and probity of George Brangam prior to setting up Brangam, Bagnall & Co;

- procurement of legal services; and

- regulatory regime for the legal profession.

Frauds perpetrated by George Brangam

and why they were not picked up earlier

5. George Brangam, the principal partner in the practice of BB & Co defrauded the health sector of at least £278,000 during a seven year period. Brangam joined the Central Services Agency’s (the Agency) Legal Services Department in 1980 and seven years later was promoted to Director of Legal Services. In 1995, he left the Agency to set up his own practice when the Department decided to market test legal services. During the period, 1996 to 2006, health bodies in Northern Ireland paid BB & Co £7 million in fees for legal services.

6. The frauds perpetrated by Brangam are yet another example of a senior person involved in public services abusing their position of trust. The Committee is appalled that it took such a long time for this apparently respectable legal services practitioner to be caught. This case sends out a very clear message that public bodies must be just as rigorous in their dealings with professionals as with other contractors.

7. Brangam had been involved in fraudulent activities for at least eight years before he was caught. In the Accounting Officer’s view, the undue trust placed on Brangam led to payments being made with insufficient evidence to support them, and this was the core of what went wrong. The Accounting Officer acknowledged that a stricter application of routine procedures may have led to these fraudulent activities being picked up earlier. The Committee considers this to be a major understatement. There is no doubt in the Committee’s mind that these controls should have led to the frauds being detected earlier and there is no excuse for such basic controls not being in place.

8. Although the Accounting Officer assured the Committee there was no evidence to suggest that similar levels of trust were shown to other firms of solicitors, the Committee is concerned that there could be further exposure in this area.

Recommendation 1

9. The Committee recommends that the Department monitors the performance of other firms providing legal services to the health sector, to ensure they are complying with guidance issued since the frauds were discovered.

10. The Committee cannot think of any instance where it is acceptable to pay public money on the basis of trust. The Accounting Officer admitted, with hindsight, that Brangam had smartly and maliciously built up his reputation to secure legitimate business and to commit fraud. The Department informed the Committee that “it now operates stringent controls, has a zero-tolerance attitude to fraud and does not trust anybody”. However, the Committee is acutely aware of the long history within the health sector of turning a blind eye to white collar crime. In an earlier PAC Report on Controls to Prevent and Detect Fraud in Family Practitioner Service Payments [3] , the Committee’s Westminster predecessors commented on the completely unacceptable position that existed with regard to the levels of controls over family practitioner service expenditure. This included dentists, doctors, opticians and pharmacists. Moreover, the Westminster PAC considered there to be an element of complacency within both the Department and the Health Boards in setting up measures to counteract these deficiencies. It is disappointing that the Department did not apply lessons learnt from this Report to its dealings with other professionals. It is clear that contracts with professionals are not scrutinised to the same extent as other contracts and the Committee does not consider it appropriate or sufficient to rely on the integrity and honesty of professionals who render services to public bodies when making payments to them.

Recommendation 2

11. The Committee considers it wholly unacceptable to dispense with basic payment checks and rely exclusively on the honesty and integrity of professionals when dealing with public services. The Committee expects departments and their sponsored bodies to apply the same rigorous standards to ensure a payment is regular, regardless of whom they are dealing with.

Weaknesses in financial procedures and compliance

12. One of the reasons why Brangam was able to execute these frauds was the health bodies’ practice of paying cheques into the solicitor’s client accounts, rather than directly to claimants. The Committee expressed its surprise that this approach was considered acceptable and that normal tried and tested market practice was not followed. The Department admitted it had no defence to that point. The Committee concurs with the Law Society that this practice was inconceivable and likely to have been a further reason why these frauds were perpetrated against Health & Social Care bodies.

Recommendation 3

13. The Department has now introduced new procedures which do not permit cheques in the settlement of legal cases to be channelled through solicitors, when there is no sensible business case for doing so. The Committee recommends that the Department carries out regular checks to ensure these new procedures are strictly applied. The Committee also calls on the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) to ensure that similar procedures are rolled out across the entire public sector.

14. In the Committee’s view, the individual frauds were very straightforward and it should not have been difficult to spot them. The C&AG’s report provides a number of examples of the types of frauds perpetrated, which fully support this assertion. The example where Brangam was able to claim a settlement twice for the same case beggars belief, and provides very little comfort that basic controls were operating in health bodies. While it is surprising that independent evidence was not sought to corroborate the first settlement request, it is remarkable that alarm bells did not ring when the second settlement was requested. The Committee is dismayed to learn from the Department that the requirement to secure appropriate independent evidence of settlements, and pay on that basis only, was established relatively recently when revised fraud prevention rules were issued following discovery of the frauds. The Department did admit that some health sector bodies were already applying that practice, through their own wit, and the Committee is astonished that the need for supporting third party evidence was not already a key control. That said, the Committee would have expected any well run finance department in a health trust or board to have such a basic procedure in place, without needing specific direction from its department.

15. When asked how he ensured compliance with procedures issued for legal claims, the Accounting Officer informed the Committee that he relied on personal assurances from chief executives and internal audit assurances. It is clear to the Committee that, in this instance, meaningful assurances were not obtained from either of these sources. The Accounting Officer acknowledged his responsibility to answer for these weaknesses and noted that it was regrettable and unacceptable that guidance was not applied. The Committee is frustrated that assurance mechanisms within the sector did not work. Given the wide remit of this Department and its large number of sponsored bodies this is of serious concern. It is important that Departmental Accounting Officers ensure that assurances from Subsidiary Accounting Officers are underpinned by hard evidence that controls are operating in practice. Clear assurance mechanisms must be established, followed and monitored across the health sector, supplemented by a programme of regular compliance audits.

Recommendation 4

16. The Committee recommends that appropriate mechanisms be put in place to provide assurance that financial procedures in respect of legal and other claims are being followed across the Health and Social Care sector. Accounting Officers need to satisfy themselves that internal audit service providers have built this area into their programme of work to ensure controls and compliance with them is tested periodically. Furthermore, internal audit should pay particular attention to instances where senior management override occurs to ensure that such action is legitimate.

Weaknesses in supervisory controls

17. The Committee has the clear impression that controls were weaker in some health bodies than in others. In the Committee’s view, Brangam targeted the health bodies he defrauded precisely because he knew that they operated in a lax control environment, and he made a calculated judgement that he could get away with it. Clearly, management with specific responsibilities for making such payments, particularly in these health bodies, were not sufficiently alert to the possibility of fraud.

18. The Committee commends the junior member of staff at Causeway Trust who raised initial concerns about payments to BB & Co but is disappointed that these concerns were not followed up promptly. This failure to act decisively raises questions about the quality of supervision within the Trust. The Accounting Officer has attributed the inadequate follow-up to lack of continuity of staff. The Committee finds the absence of such a basic control disheartening. Supervisory negligence is explored further at paragraph 43.

19. The Committee considers it essential that staff involved in processing payments to contractors are well trained, alert to the possibility of fraud and of the need to comply with controls. The Committee endorses the Accounting Officer’s view that training and leadership of staff working in this area must be reviewed to strengthen controls and secure continuity, particularly in such a period of change within the health service.

Recommendation 5

20. The Committee recommends that training needs and leadership in the area of contract claims is reviewed within the health sector and rolled out as a matter of urgency. The Department should also consider the extent of the fraud awareness training currently delivered within the health sector.

Wider impact on other contracts within the health sector

21. In this instance the controls over contractual payments were found to be so lax that the Committee’s confidence in the capacity of the health sector to exercise effective control over payments to contractors has generally been eroded.

Recommendation 6

22. The Committee wants assurance that the slipshod, unprofessional practices in this case do not apply elsewhere and recommends that internal audit, throughout the health sector, gives sufficient weight to the audit of contracts. The Committee also calls upon the C&AG to pay particular attention to such contracts as part of NIAO’s routine financial audit work.

Adequacy of the Department’s

investigation

23. Following the initial complaint about Brangam in August 2006, the Law Society took decisive action which led to the practice being closed down less than a month later. When asked by the Committee why it had taken the Department seven months to commission its own forensic investigation, the Accounting Officer advised that this time was required to initiate the procurement process, and be clear on the scale and nature of the investigation required.

24. The Committee is not clear why the Department waited until the Law Society’s forensic investigation was completed, given that the Law Society’s Compensation Fund may have been liable and accordingly, the Law Society would have different interests in the investigation.

Recommendation 7

25. Procurement processes in the public sector often take many months to complete. The Committee recommends that all Departments review their contingency arrangements to ensure they have:

(a) an up to date Fraud Response Plan in order to minimise the time required to think through the scope and nature of any investigation once a fraud is notified; and

(b) appropriate standby measures in place to allow them to get forensic investigations up and running quickly.

26. The Committee notes the Accounting Officer’s view that this delay did not impede a thorough and effective investigation but is unconvinced that the Department provided the necessary leadership or the decisive action required. The Accounting Officer notes that he is satisfied that all health sector bodies were clear about the need to secure their records, however the Committee is concerned that if Brangam had any accomplices within the health sector, key records may have been destroyed. In any case, it is the Committee’s view that when faced with allegations of fraud, public bodies must act swiftly to ensure further loss is prevented. In this instance, the delays by the Department were wholly unacceptable. The Committee’s predecessor also made the same point about the need for vigorous and prompt investigation when reporting on the Internal Fraud in LEDU in 2002 [4] .

Scope of the investigation

27. The C&AG’s report indicated that the Department’s forensic investigation was impeded because in 71 cases, relevant files and other information could not be found at health sector bodies or at BB & Co, and therefore, no conclusion could be reached on whether irregularities had occurred. In the Committee’s view, greater efforts should have been made to locate all the missing information or attempts should have been made to reconstruct files from other sources, e.g. claimant solicitor files or Court records. At the evidence session, the Accounting Officer stated he was confident that the full amount of fraud had been uncovered as there was very little evidence of fraud in non-clinical negligence cases; the sample of cases tested was sufficient to reach a conclusion and that, as further files had subsequently been found in recent days, he was no longer concerned about insufficient information.

28. The Committee does not set much store by the Accounting Officer’s assurance that he is less concerned now that files have turned up. Far from reassuring the Committee, this gives further cause for concern over the quality of record-keeping and control maintained by health bodies, and gives the impression of a high degree of confusion. The Accounting Officer explained that one of the reasons why files were not available was because they may have been disposed of under routine and legitimate procedures. The Committee is not clear if the files now found were previously thought to have been disposed of under these procedures and would welcome a fuller explanation from the Department.

29. In the Committee’s view, this is a tacit admission that the preliminary investigation in this area was deficient and the Committee can only surmise that the unavailable information has now been discovered through last minute work completed before the evidence session.

30. The Department gave a commitment that fresh guidance would be issued for records management and expects DFP’s response to the HANI Report [5] , regarding the retention of financial records associated with any investigation for 10 years, to be taken into consideration.

Recommendation 8

31. The Committee is very concerned about the apparent inadequacy of health bodies’ records management systems if records have now appeared that were previously considered to be legitimately destroyed, and recommends that the Department provides a fuller explanation.

Recommendation 9

32. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Department is reviewing its records management guidance and recommends that the findings of this Report, and DFP’s response to the Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland Report are considered when drafting it. New guidance issued must be both understandable and comprehensive.

33. When asked why the investigation had only reviewed records from 1999, when Brangam had provided services to the health sector as a private contractor since 1995, the Accounting Officer advised that additional work had been completed in this area after the C&AG’s report was compiled. This provided the Department with confidence that no such problems existed during that period.

34. Records of work completed by Brangam before he left the Agency were not examined because the Department considered the risk of fraud to be minimal due to cost controls existing in such public service organisations. While the Committee accepts the view that the risk of similar fraud being perpetrated in the Agency was minimal, bearing in mind concerns about his conduct and probity, Brangam may well have been engaged in other types of fraudulent activity. The Committee notes that the Department judged that based on the level of risk, there was no reason to pursue this, however it considers that this should have been included in the terms of reference for this investigation.

35. The Accounting Officer also assured the Committee that, although less attention was given to the £7 million in fees because the majority was paid under a fixed fee arrangement, there was no fraud involved in these payments. The Committee finds this assurance somewhat surprising as there is a clear possibility that such invoices may also have been inaccurate.

Consideration of collusion between Brangam and health bodies

36. The Committee explored with the Department why the possibility of collusion was not considered. The Department advised there were insufficient grounds for it to investigate this, although it did admit that it could not be ruled out. Furthermore because of Brangam’s elaborate concealment methods, it could not know everything going on in the firm or the degree to which Brangam might have had accomplices. The Department argued that it would have been unlikely for there to be effective collusion in six different organisations. The Committee notes that 82% of the frauds identified were concentrated in two health sector bodies, which would either suggest that the control environment in both of them was very weak and this was known to Brangam or it may suggest collusion. In the Committee’s view, it seems unlikely that this level of fraud could have been perpetrated single handedly by one individual, and notes that the bookkeeper employed by Brangam subsequently worked for another law firm and fraudulently extracted monies there. The Committee would have expected the Department to have conducted an initial investigation before prematurely ruling out the possibility of collusion, and notes that this area was not included within the forensic accountant’s terms of reference.

37. At the very least, the Committee would have expected the investigation to look at the hospitality registers of the defrauded health bodies and talk to staff to see if there was knowledge of hospitality not included.

Recommendation 10

38. The possibility of collusion should never be ruled out prematurely and always be carefully explored in the terms of reference for any fraud investigation. When major contract fraud occurs, the Committee expects that investigations would automatically cover hospitality registers and registers of interest. The Committee requires the Department to report back on details of any gifts or hospitality offered by Brangam to health bodies receiving services, and details of any interests registered by health service staff in connection with BB & Co.

Consideration of supervisory negligence

39. When the previous Assembly’s PAC examined the fraud in the former LEDU in 2002, one of the key recommendations was that fraud investigations should address whether supervisory negligence is a contributory factor. Once again, the Committee considers the quality of supervision to have been far below what was expected. If there was no collusion, it is the Committee’s view that there was undoubtedly a very lax supervisory regime at these health bodies. Brangam clearly took full advantage of these weaknesses in control. The fact that the possibility of supervisory negligence was not investigated further by the Department, to determine whether it may have contributed to the circumstances that allowed these frauds to be perpetrated, sends out the wrong message on how inadequate stewardship of public funds should be dealt with. One way of ensuring that supervisory negligence is covered by a fraud investigation would be to include it within a Fraud Response Plan.

Recommendation 11

40. The Committee recommends that terms of reference for forensic investigations should be pitched sufficiently widely to identify the full extent of the fraud and the possibility of supervisory negligence. DFP should also ensure that departmental guidance on fraud investigations includes consideration of supervisory negligence as a matter of course. The Committee expects in cases of major fraud that departments should consult with the NIAO to adequately scope their terms of reference.

41. It is disappointing that the delay in commissioning the investigation was not effectively used to draft sufficiently wide terms of reference. The Committee is frustrated by the inadequacies of the Department’s investigation in this matter, particularly because money has been recovered in full for the fraudulent activities identified to date and more could be recouped if further evidence of fraud was found. It is worth repeating the point the Committee made when examining the fraud in Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland [6] that any fraud of this nature imposes additional burdens on the public purse over and above the amount defrauded. The Department has estimated that the cost of the Brangam investigation, including legal and forensic accountant expenditure, to be around £123,000. It expects to recoup this in full as the Court Judgement awarded the Department costs. However, it seems from the information supplied by the Department that it has not attempted to either quantify or recoup the cost of time spent by its own staff in handling the investigation.

Concerns over the conduct and probity of George Brangam prior to setting up

Brangam Bagnall & Co

Conduct and probity of George Brangam

42. Once Brangam’s frauds were exposed publicly, new allegations about his conduct, behaviour and probity, over three decades, including his time with the Agency, began to emerge. These included an allegation in 1987, for which no disciplinary action was taken, and a harassment allegation in the mid-nineties. The Accounting Officer acknowledged that there were concerns, but there was no evidence that the investigation in 1987 was brought to the attention of the Department and the issue was resolved to the Agency’s satisfaction. He admitted that questions were left hanging in the air, but there were no grounds for taking action as there was no substantive evidence.

43. The Committee finds it surprising that this matter was not brought to the attention of the Department. Had there been a proper mechanism for information sharing those health bodies who had entered into contracts with BB & Co may have subjected their payments to this practice to a higher level of scrutiny and picked the fraud up earlier.

Recommendation 12

44. Although the Committee welcomes the recovery of both amounts defrauded and costs of £123,000, it is not satisfied that all options for recovery were fully explored in this case. The Committee recommends that when fraud occurs departments should use all means at their disposal to maximise the recovery of public funds.

Recommendation 13

45. The Committee reiterates a recommendation made in its Report on HANI that, in situations where it is in the public interest to protect standards in public life and the public purse, there should be a mechanism for information sharing.

Circumstances surrounding Brangam’s departure from the Central Services Agency

46. In 1994, in line with Government policy at the time, the Department decided that legal services provided by the Central Services Agency should be market tested, i.e. the in-house operation would have to compete with private sector suppliers. At that time George Brangam occupied the post of Director of Legal Services and was the Chief Legal Advisor at the Agency. In September 1994, at the outset of the market testing process Brangam had made clear his intention to set up his own private sector company to provide such services. In the event he established his practice in January 1995, but remained in his public sector post until March 1995. The Committee considers that in the six months before his departure from the Agency, Brangam had a major conflict of interest. He had a vested interest in ensuring that the in-house operation which he directed was weak as this would enable him to capture a greater share of the work when it was out to tender. In the Committee’s view Brangam’s continued involvement with the Agency, at a senior management level, must have had a detrimental impact on the morale of Agency staff who wished to continue to serve in the public sector.

47. The Committee is amazed that Brangam had any involvement in the procurement process, given the fact that he had indicated his intention to resign and create a private sector company to provide legal services. The Department has accepted with hindsight that Brangam should not have been involved in interim arrangement meetings, but maintains that his exclusion from key decisions and processes was enough to satisfy public probity. The Accounting Officer informed the Committee that both Agency management and the Department deliberately designed the procurement process to be independent of him and, while recognising the conflict of interest that existed, considered it to be managed.

48. The Committee does not agree. Conflicts of interest must either be managed or avoided. This was an unmanageable conflict. It is hardly surprising that the Agency’s attempts to manage it were unsuccessful. Brangam was heading up the in-house legal team at the same time as he was setting up his private practice, which would be in direct competition with the in-house legal team. The Committee has previously expressed its view in the HANI Report that being soft on conflicts of interest is a recipe for disaster. The Westminster PAC has also noted in the 2006 LEDU Report [7] that avoiding unmanageable conflicts not only provides reassurance to the public that decisions taken in public bodies are entirely based on what is in the public interest, but protects individuals from any suspicion of bias.

49. The Committee has a very clear view as to how this unedifying situation should have been handled. At the very beginning of the market testing process the Department should have made it clear to Brangam that he would have to make a choice before the process could progress to the next stage. He could bid for work as a private sector contractor, but if he wished to do so, he would have to resign from the public sector by a specified date. Alternatively he could remain in his public sector post, but if he wished to do so, he should play absolutely no part in any private sector bids.

Recommendation 14

50. This is another example of a case where the public sector has tried to manage a conflict of interest that should have been avoided. The Committee recommends that conflicts of interest must be identified at an early stage. Departments need to better assess the risks involved in trying to manage a conflict if they choose to do so and then address the conflict immediately and effectively. Once again DFP is called upon to give clearer guidance on the types of situation where conflicts should be avoided, rather than managed.

Procurement of legal services

Development of an open market

51. Until 2006-07, BB & Co received 70% of the payments made to legal service providers (other than the Agency) despite 23 other firms being on the Select List. Of the £30 million spent on legal services over the period 1996 to 2006, £11 million was paid to the private sector and £7 million of this was paid to Brangam, Bagnall & Co who effectively became a private sector monopoly supplier.

52. The Accounting Officer has admitted that the philosophy at the time of maximising the scope for competition did not work effectively and that Department procedures should have been tighter. The Committee is concerned at how easily Brangam was able to use his inside knowledge of the health sector to gain the lion’s share of the market, and the impact on other firms unable to get a slice of this business. In the Committee’s view, the Department should have monitored this situation and acted promptly when it was clear that an effective open market never developed for legal services, particularly when concerns were raised by elected representatives in the Assembly and elsewhere as far back as 2000 about the disproportionate amount of business given to BB & Co.

Recommendation 15

53. When procurement arrangements are being put in place they should always be designed in a way which provides regular opportunities for new suppliers to enter the market. In the Committee’s view, where a list of approved providers is used, departments should regularly monitor the allocation of work to firms to assess if an open market has, in fact, developed. Where the market does not grow as expected, departments should take prompt action to prevent a monopoly situation from arising, a firm becoming over stretched, or over dependency on one provider. The Committee recommends that DFP ensures appropriate guidance to this effect is issued to all departments.

Duration of the Select List

54. The Select List was established in April 1996, with a shelf life of three years and an option to extend for a further three years. It is surprising that the option to extend, for such an important and sensitive service, was availed of for the maximum three year period allowed. However, for the list to have then been extended by an additional six years is frankly unbelievable. One of the reasons why the Select List had to be extended so many times was that two attempts to run a fresh competition had to be abandoned. In the first instance, the bids could not be ranked against each other. The Accounting Officer informed the Committee that he had no strong grounds for defending what happened during the process and that there were unacceptable delays, resulting in a protracted process that failed to produce any proper outcomes.

Lessons arising from the collapsed procurement exercise

55. The Committee is astonished that despite Central Procurement Directorate (CPD) involvement, in what should have been a relatively straightforward procurement exercise, the competition was designed in a way which did not enable the bids to be compared. This indicates an insufficient level of competency on the part of those involved in designing this process. The Treasury Officer of Accounts (ToA) advised the Committee that CPD assumed that certain information would be available for the evaluation when the tenders came in and one of the reasons why the exercise collapsed was because it was not. Another reason suggested by the ToA was the fact that a single competition had been run for 21 health bodies with different requirements. The Committee agrees with the ToA that, in such situations, strong leadership and direction is needed to get agreement among all the bodies. It is the Committee’s view that the basic application of common sense should have suggested fairly early on in the process that this exercise was doomed to failure and, on this basis, it is not surprised that it collapsed.

Recommendation 16

56. The Committee is seeking assurance from the Department that there will be no further cases of competitions being abandoned due to its inability to assess and compare bids.

Recommendation 17

57. The Committee’s view is that evaluation criteria should be absolutely clear at the start of a procurement process. Furthermore, relevant and accurate data must be provided to tenderers to enable them to assess the services they will be required to provide and to submit their bids. The Committee recommends that DFP consider this recommendation within the context of its existing procurement guidance.

58. The Committee is also dismayed to learn that the Department has failed to honour commitments made to the previous Public Accounts Committee in 2002 [8] to put in place a new legal services contract which secured value for money by April 2004. Earlier implementation of a new legal services contract may have reduced Brangam’s opportunities for carrying out fraud.

Recommendation 18

59. The Committee is concerned that the Department has failed to fulfil assurances previously given. It expects departments to respond quickly and appropriately to address all assurances provided to the Committee through regular monitoring of progress.

The Transfer of cases following discovery of the frauds

60. Following the closure of BB & Co by the Law Society, Gary Daly, who previously worked in BB & Co, set up a new legal practice, MSC Daly Solicitors. He then approached the Department regarding the provision of legal services to health bodies. Having obtained legal advice, the Accounting Officer advised health bodies, that while he was not endorsing the firm, there was no impediment in law or procurement practice which would preclude the use of MSC Daly Solicitors. Gary Daly is not, nor has been, under any investigation for fraudulent activity.

61. The Committee asked the Department why it said to health sector bodies that they could use MSC Daly, when it did not start its own investigation until February 2007 and therefore could not be sure in September 2006, if there was any collusion within the practice. The Department advised that its decision regarding the use of MSC Daly was based on a quick and immediate investigation into the frauds which did not flag up any concerns about anyone other than Brangam, and that this was a difficult judgement call between balancing the risk that something may emerge later against the risk that the case may not be handled well. The Department also noted that advice had been sought from their legal and procurement advisors before taking this action. Although the intention was that MSC Daly would provide continuity of service, the Department acknowledged that new cases had also been transferred to them. The Committee considers that it would have been prudent to suspend dealings with any members of BB & Co following the closure of the practice, until all investigations had been completed. Furthermore, this firm had not been subject to any form of tendering exercise and comprised staff, previously employed by BB & Co.

Recommendation 19

62. The Committee recommends that, in cases like this, where allegations of fraud or other impropriety exist, public bodies should consider suspending financial dealings with those directly, and indirectly, involved until the main investigation has been completed.

63. The Law Society told the Committee that Mr Daly’s position and accountability as a partner in BB & Co is subject to ongoing, potentially disciplinary, activity by the Law Society. Although insurers were satisfied that Mr Daly was an innocent party and therefore not party to the frauds, the Law Society had to consider whether he, as a partner, should have been in a position to ensure accounts were not falsified. Mr Daly has registered his position on this in a letter to the Committee (see Appendix 3).

Regulatory regime for the

legal profession

64. The Law Society acts as the regulatory authority governing the education, accounts, discipline and professional conduct of solicitors and has strict rules regarding how client funds are accounted for and banked. These accounts are inspected by accountants employed by the Law Society.

Frauds not detected through regulatory inspections

65. As stated in paragraph 18, most of Brangam’s frauds should have been detected by health bodies through application of basic controls, but they could potentially have been detected by the Law Society. All solicitors are required to submit an annual accountant’s report to the Law Society to show that they have handled clients’ money properly and regular inspections are also carried out by internal accountants employed by the Law Society. The Committee asked the Law Society why none of Brangam’s frauds were detected. The Law Society responded that, based on the work of its forensic accountants, this was because these frauds were well concealed with a paper trail covering all money leaving the client accounts, making the internal accountants’ scrutiny role very difficult. The Law Society also made the point that the sheer volume of transactions going through BB & Co’s clients’ accounts, from 11 different health bodies which provided lump sum payments to the practice, made it difficult for internal accountants to spot these frauds. Moreover the internal accountants’ approach relied on sampling and unless the frauds were picked up as part of the sampling they would not be detected.

66. The Committee is disappointed that the Law Society’s regular inspections of BB & Co identified no problems other than a minor issue in 2001 and notes the Law Society’s belief that adequate precautions were not taken when examining the various sums paid into the client accounts of the health bodies. The Committee finds it surprising to learn that as late as 2004, the practice of Brangam Bagnall & Co received a Quality Award from the Law Society. The Committee welcomes the fact that the Law Society, as a result of this unfortunate case, has learned specific lessons in terms of its own oversight of client accounts. This has led to advice being drawn up by the forensic accountants involved in the investigation and this has been shared with accountants who report annually on solicitors’ practices.

Complaints raised and disciplinary issues arising in Brangam, Bagnall & Co

67. The Law Society informed the Committee that two complaints had been made to them against Brangam or his practice, during the period in which he practised. One in 2001 which led to an investigation carried out on the Law Society’s behalf concerned funds placed in the firm’s office account rather than its clients’ account. This was considered to be an accounting issue which was regularised. The other related to the 2006 frauds. However an additional allegation relating to an event that had occurred over 20 years previously did not come to the Law Society’s attention until after Brangam’s fraudulent activities were publicly exposed. Given the concerns and rumours that surrounded Brangam’s conduct and probity over the years, the Committee shares the Law Society’s disappointment that public concerns were not conveyed to them earlier. The Committee was surprised to learn that the Law Society does not operate a whistleblowing policy. It is difficult for the Committee to understand how any regulatory body can do its job effectively without having a fully functioning whistleblowing policy in place.

Extent of abuse in the profession

68. Since 1998, the Law Society has intervened in solicitors’ practices 63 times, with some firms being investigated more than once. The Law Society made the point that intervention often results in a satisfactory conclusion, though twenty firms had been closed down. The Committee is astonished at the number of interventions, including cases of fraud, within such a small society as Northern Ireland and notes that there are similar problems within other jurisdictions.

Publication of professional misconduct findings

69. The Committee notes the Law Society’s view that it would not be appropriate to make key findings and reports available to public bodies, until the independent solicitor’s disciplinary tribunal makes its decision, and welcomes its suggestion that the onus be placed on any firm or individual tendering for a legal services contract to disclose details of any professional conduct investigations and findings. The Law Society said that a list is available and published. The Committee was unable to pick this up easily from the Law Society’s website and recommends that such a link is considered.

Review of current regulatory regime

70. The Committee notes that the Government established a Legal Services Review Group in 2005 to recommend to the Minister of Finance and Personnel how legal services should be regulated in Northern Ireland. Following a consultation process, the Group published a Report on Legal Services in Northern Ireland focusing on complaints, regulation and competition detailing 42 recommendations which should improve the provision of legal services. The Committee understands that the report is currently under consideration by the Minister of Finance and Personnel. The Group’s recommendation on regulation of the profession, whereby the profession would continue to discharge its own regulatory responsibilities, subject to enhanced oversight arrangements, is of particular interest to the Committee.

Recommendation 20

71. The Committee would welcome details of what action, if any, has been taken by DFP following the recommendations of the Legal Services Review Group.

Points for the Law Society to consider

72. The Committee welcomes the proactive approach adopted by the Law Society in terms of lessons learnt and has written to the Law Society recommending that:

- it should consider introducing a whistleblowing policy, which clearly sets out the protection afforded to a whistleblower and be easily accessible through the Law Society’s website;

- it informs the Committee of the outcome of its ongoing inquiries relating to the Brangam case;

- it consults with its members to ensure there is no knowledge in the profession of other wrong-doing concerning Brangam; and

- findings of the Solicitor’s Disciplinary Tribunal are more readily available on the Law Society’s website and widely published.

73. The Committee also welcomes the Law Society’s suggestion that contracts with solicitors should allow public bodies to regularly review relevant case files held by them and encourages the Agency to bear this in mind if they decide to sub-contract any of their work.

Recommendation 21

74. The Committee recommends that where legal services are provided by private sector firms, public bodies should ensure they have the right of access to inspect their own case files, as and when desired. These rights should be exercised from time to time.

[ 1 ] Controls to Prevent and Detect Fraud in Family Practitioner Service Payments, Session 1998/99, Eleventh Report, 6 May 1999 (HC 123)

[ 2 ] Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland: A Case Study in financial management and the public appointments process, Session 2007/2008, Fifteenth Report, 12 June 2008, (36/07/08R)

[ 3 ] Controls to Prevent and Detect Fraud in Family Practitioner Service Payments, Session 1998/99, Eleventh Report, 6 May 1999 (HC 123)

[ 4 ] Internal fraud in the Local Enterprise Development Unit, Session 2001/2002, Eleventh Report, 26 June 2002 (11/01/R)

[ 5 ] Hospitality Association of Northern Ireland: A Case Study in financial management and the public appointments process, Session 2007/2008, Fifteenth Report, 12 June 2008, (36/07/08R)

[ 6 ] Tackling Public Sector Fraud, Session 2007/2008, Fifth Report, 13 December 2007, (13/07/08R)

[ 7 ] Governance Issues in the DETI’s former LEDU, Session 2005/2006, Forty-Sixth Report, 18 May 2006 (HC 918)

[ 8 ] On 19 September 2002, the Assembly’s Public Accounts Committee considered the NIAO Report on Compensation Payments for Clinical Negligence, 5 July 2002, NIA 112/01

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

of the Committee Relating

to the Report

Thursday, 4 December 2008

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Maskey (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr George Robinson

Mr Jim Shannon

In Attendance: Mr Damien Martin (Clerk Assistant)

Ms Alison Ross (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Gillian Lewis (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Jim Wells

The meeting opened at 1.30pm in public session.

The Deputy Chairperson welcomed Mr Kieran Donnelly, Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General, and Mr David Thomson, Treasury Officer of Accounts (TOA) to the Committee meeting.

1. Apologies.

The apologies are listed above.

2. Evidence on the NIAO Report ‘Brangam Bagnall & Co – Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated against the Health & Personal Social Services’.

(a) The Committee took oral evidence on the NIAO report ‘Brangam Bagnall & Co – Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated against the Health & Personal Social Services’ from Dr Andrew McCormick, Accounting Officer, Department Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), Mrs Julie Thompson, Director of Finance, DHSSPS, and Mr Dean Sullivan, Director of Planning and Performance, DHSSPS, and answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

2.03pm Ms Purvis joined the meeting.

2.07pm Mr Burns left the meeting.

2.20pm Mr Burns rejoined the meeting.

3.12pm Mr Dallat left the meeting.

3.12pm Mr Beggs left the meeting.

3.15pm Mr Dallat rejoined the meeting.

3.20pm Mr Shannon left the meeting.

3.25pm Mr Shannon rejoined the meeting.

Members requested that the witnesses should provide additional information to the Clerk on some issues raised as a result of the evidence session.

3.45 pm Mr Burns left the meeting.

3.45pm The evidence session finished and the meeting was suspended.

4.00pm The meeting resumed in public session.

(b) The Committee took oral evidence on the NIAO report ‘Brangam Bagnall & Co – Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated against the Health & Personal Social Services’ from Mr Donald Eakin, Senior Vice President, The Law Society, and Mr James Cooper, past Senior Vice President, The Law Society, who answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

4.43pm Mr Dallat left the meeting.

4.47 Mr Robinson left the meeting.

5.03pm Mr McLaughlin left the meeting.

Members requested that the witnesses should provide additional information to the Clerk on some issues raised as a result of the evidence session.

5.05pm The evidence session finished and the witnesses left the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday, 5 February 2009

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Maskey (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns

Mr John Dallat

Mr Trevor Lunn

Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr George Robinson

Mr Jim Shannon

Mr Jim Wells

In Attendance: Ms Alison Ross (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Roisin Donnelly (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr John Lunny (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mitchel McLaughlin

The meeting opened at 2.01pm in public session.

2.05pm Mr Burns joined the meeting.

2.07pm Ms Purvis joined the meeting.

2.11pm The meeting went into closed session.

2.20pm Mr Wells joined the meeting.

2.53pm Mr Wells left the meeting.

5. Consideration of the Committee’s Draft Report on ‘Brangam Bagnall & Co: Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated Against the Health & Personal Social Services’.

Members considered the draft report paragraph by paragraph.

The Committee considered the main body of the report.

Paragraphs 1 – 9 read and agreed.

Paragraph 10 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 11 – 15 read and agreed.

Paragraph 16 read, amended and agreed.

3.04pm Mr Wells rejoined the meeting.

Paragraphs 17 – 26 read and agreed.

Paragraph 27 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 28 read and agreed.

Paragraph 29 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 30 – 38 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 39, 40 and 41 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 42 – 43 read and agreed.

Insert new paragraph 44.

Paragraphs 45 – 49 read and agreed.

Paragraph 50 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 51 – 53 read and agreed.

Paragraph 54 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 55 – 64 read and agreed.

3.29pm Mr Burns left the meeting.

Paragraphs 65 and 66 read, amended and agreed.

3.33pm Mr Lunn left the meeting.

Paragraph 67 deleted.

3.34pm Mr Lunn rejoined the meeting.

Paragraph 68 read and agreed.

Paragraph 69 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 70 – 75 read and agreed.

3.37pm Ms Purvis left the meeting.

The Committee considered the Executive Summary.

Paragraphs 1 – 2 read and agreed.

Paragraph 3 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 4 – 14 read and agreed.

Agreed: Members ordered the report to be printed.

Agreed: Members agreed that the Chairperson’s letters to the Accounting Officer, Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety and to The Law Society of Northern Ireland be included in the Committee’s Report, together with the response letters from the Accounting Officer, Department Health, Social Services and Public Safety, and the Law Society of Northern Ireland. Correspondence received from Mr Gary Daly will also be included in the Committee’s report.

Agreed: Members agreed the report would be embargoed until 00.01am on Thursday, 26 February 2009, when the report would be published.

Agreed: Members agreed that the Clerk seek advice from the Press Office regarding publicity for the launch of the report.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

4 December 2008

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Paul Maskey (Chairperson)

Mr Roy Beggs (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns

Mr Jonathan Craig

Mr John Dallat

Mr Trevor Lunn

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr George Robinson

Mr Jim Shannon

Witnesses:

Dr Andrew McCormick |

|

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety |

Mr James Cooper |

|

The Law Society of Northern Ireland |

Also in attendance:

Mr Kieran Donnelly |

|

Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General |

Mr David Thomson |

|

Treasury Officer of Accounts |

1. The Chairperson (Mr P Maskey): We will now consider the Comptroller and Auditor General’s report on ‘Brangam Bagnall and Co: Legal Practitioner Fraud Perpetrated against the Health and Personal Social Services’. We will also consider the Audit Office’s memorandum on contracting for legal services in the health and social care sector.

2. It is unusual for the Committee to consider a report and a memorandum in one session, but as the memorandum supplements the report, it has been decided to do so on this occasion.

3. Two sets of witnesses will provide evidence, and we will hear that evidence in two separate sessions. First, we will hear from the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, and following a short break, we will reconvene to hear from the Law Society. After the Law Society finishes, approximately 10 minutes will be available for departmental officials to make any closing remarks if they wish.

4. I welcome the following witnesses from the Department: Dr Andrew McCormick, who is the Department’s accounting officer; Mrs Julie Thompson, director of finance; and Mr Dean Sullivan, the director of planning and performance.

5. Today’s session is very full; however, given the concern about the report, there will be a number of questions from me and other Committee members. I ask you to keep your answers brief and not to labour your points so that members are allowed time to ask their questions.

6. Dr McCormick, perhaps you will introduce your colleagues and outline their responsibilities.

7. Dr Andrew McCormick (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety): Thank you. My colleagues are Mrs Julie Thompson, who is acting as the senior finance director in the Department, and Mr Dean Sullivan, who is director of planning and performance and has the responsibility for procurement.

8. The Chairperson: Thank you, Dr McCormick. As far as the Committee is aware, the fraud in question is one of the largest committed over the longest period of time. The Department must feel extremely uncomfortable at having to respond to this report, and you cannot be happy with the amount of time that it has taken for the fraud to be uncovered.

9. Dr McCormick: I assure the Committee that we feel very uncomfortable about what has happened, and I will emphasise all that we have done to prevent a recurrence and how we have dealt with the consequences of this unacceptable breach of trust, guidelines and procedures.

10. We assure the Committee that the Department has a zero-tolerance attitude to fraud. We have undertaken a range of detailed work, especially since 2004, to make sure that the procedures that apply throughout the health and social care system are sound, based on good practice and ongoing evidence, and are kept under review so that we retain accountability from all the bodies in order that those responsibilities can be fulfilled.

11. I should point out that the full amount from this fraud was recovered. The public purse was reimbursed with what I am confident was the full amount. We have looked hard for additional evidence — even subsequent to the report — and based on that, I am strongly confident that the full amount was discovered and that no individual other than George Brangam, who was the primary perpetrator, was involved.

12. We have stringent controls and a zero-tolerance attitude, and we do not trust anybody. Even if someone is well known, or is a colleague, or a former colleague, we ensure that any payments made are based on evidence.

13. Insufficient evidence is at the core of what went wrong in this case; payments were made without sufficient evidence. We have taken steps to prevent that from occurring again.