Session 2008/2009

First Report

COMMITTEE ON PROCEDURES

Report on

the Inquiry into

Private Legislation

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee relating

to the Report and the Minutes of Evidence

Ordered by The Committee on Procedures to be printed 8 October 2008

Report: 9/08/09R Committee on Procedures

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Committee on Procedures

Membership and Powers

The Committee on Procedures is a Standing Committee of the Northern Ireland Assembly established in accordance with paragraph 10 of Strand One of the Belfast Agreement and under Assembly Standing Order 54. The Committee has 11 Members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The Committee has the power to:

- Consider and review on an ongoing basis the Standing Orders and procedures of the Assembly;

- Initiate inquiries and publish reports;

- Update the Standing Orders of the Assembly for punctuation and grammar; and

- Annually republish Standing Orders

The Committee first met on 16 May 2007.

The Membership of the Committee since its establishment on 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

- Lord Morrow (Chairman)

- Mr Mervyn Storey (Deputy Chairman)

- Mr Francie Brolly

- Lord Browne

- Mr Mickey Brady *

- Mr Raymond McCartney

- Mr David McClarty

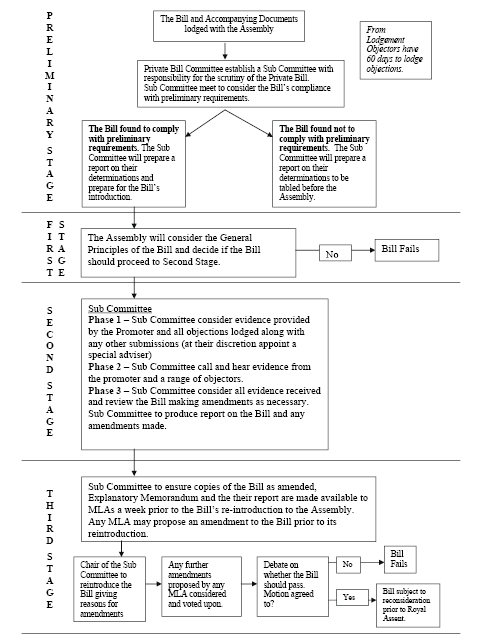

- Mr Adrian McQuillan

- Mr Sean Neeson

- Mr Declan O’Loan

- Mr Ken Robinson

* Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mr Willie Clarke as of 20 May 2008.

Table of Contents

Report

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings relating to the Report

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Executive Summary

1. At its meeting on 30 May 2007 the Committee on Procedures agreed to undertake an inquiry to address the need for procedures for taking private legislation through the Northern Ireland Assembly.

2. Private legislation is a bill for the purpose of obtaining for an individual, body corporate or an unincorporated association of persons particular powers, exemptions or benefits in excess of or in conflict with general law and includes a bill relating to the estate, property, status or style, or otherwise relating to the personal affairs, of the promoter.

3. As part of its initial scrutiny of private legislation, the Committee sought comparative research on procedures in other legislatures and arranged best practice visits to the Scottish Parliament, Westminster and the Dáil. In its call for evidence the Committee received nine written submissions and took oral evidence from six organisations.

4. An analysis of the evidence highlighted a number of key issues which included: the proposed Assembly stages for private bills; application of fees; objections to a private bill; private bill committees and hybrid bills.

5. From the evidence received, the Committee considered that the stages of a private bill should reflect those in place for public bills for the Assembly. These include: Preliminary Scrutiny; Introduction (first stage); Second Stage; Committee Stage; Consideration Stage; Further Consideration Stage and Final Stage. The Committee’s consideration of each of these stages is covered separately in the report.

6. This report represents the outcome of the Committee’s consideration of the inquiry into private legislation. The key areas that the Committee focused on relate to the importance of private bills undergoing preliminary scrutiny with tests of appropriateness applied before they are introduced to the Assembly; the private bill committee being allowed the power to make amendments; and the promoter and objector being able to present their case and cross examine each other during the Committee Stage. Also, highlighted within the report are the need for possible adjournment of Consideration Stage, the introduction of appropriate fees and criteria for the assessment of objections.

7. In conclusion, the report contains 26 recommendations which aim to put in place a robust process with an efficient and effective set of procedures for taking private legislation through the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Summary of Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bills should undergo a preliminary scrutiny before they are introduced to the Assembly and that the tests for the appropriateness of a private bill should be carried out at pre introductory stage.

Recommendation 2

The Committee recommend that an official of the Assembly (to be known as the Examiner of Private Bills) should undertake a preliminary scrutiny of the bill with a view to reporting to the Speaker on whether it meets the special requirements for private bills as laid down in Standing Orders.

Recommendation 3

The Committee recommend that the promoter must be able to demonstrate to the Examiner of Private Bills that the bill meets a number of criteria before being eligible for introduction.

Recommendation 4

After due consideration the Committee recommend that the stages for private bills should, as far as possible, reflect those in place for public bills for the Assembly.

Recommendation 5

The Committee on Procedures recommend that the introduction of a private bill will be an announcement by the Speaker that a private bill has been received and will now be published.

Recommendation 6

The Committee recommend that there should be a minimum of 60 working days between first and second stage.

Recommendation 7

The Committee recommend that the private bill committee established at first stage should report to the Assembly on the principles of the bill and invite, receive, assess and allow or disallow objections.

Recommendation 8

The Committee recommend that both the promoter and the objectors be allowed to present their case to the private bill committee, are able to call witnesses to support their evidence, that the promoter and objector be allowed to cross examine one another under the direction of the committee and be allowed legal representation.

Recommendation 9

The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bill committees should have the power to amend a bill in committee.

Recommendation 10

Where no objections have been received, the Committee recommend that the private bill be referred to a private bill committee.

Recommendation 11

The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Consideration Stage of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill.

Recommendation 12

The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Further Consideration Stage of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill.

Recommendation 13

The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Final Stage, Reconsideration Stage and Royal Assent of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill.

Recommendation 14

The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bills should not be subject to the Standing Order which provides for accelerated passage.

Recommendation 15

The Committee on Procedures recommend that where a bill has not completed its passage by the end of an Assembly session it shall be carried forth and its passage continued into the next session.

Recommendation 16

The Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill shall not be carried forth if the Assembly stands dissolved or is suspended.

Recommendation 17

The Committee on Procedures recommend that it will be appropriate for the Assembly Commission to apply a fee of £5,000.00 to the promoter of a private bill to cover the administration costs that will arise from the Assembly Stages of the bill.

Recommendation 18

The Committee on Procedures recommend that fees for charitable religious and educational organisations and for literary or scientific purposes from which no private profit or advantage is derived be reduced by 75%.

Recommendation 19

The Committee recommend that late objections will be allowed in special circumstances.

Recommendation 20

The Committee on Procedures recommend a list of criteria for an objection to a private bill.

Recommendation 21

The Committee recommend to the Northern Ireland Assembly Commission that the fee for an objection be set at £20.00 and in the event of a withdrawal of the objection, is non refundable.

Recommendation 22

The Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill committee in the Assembly has a membership of five appointed by motion from the Business Committee.

Recommendation 23

The Committee on Procedures recommend that the quorum of the private bill committee will be three and full attendance of the membership will be required unless special circumstance prevents a Member from attending.

Recommendation 24

The Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill committee will elect its chairperson and deputy chairperson at its first meeting and that voting will be by simple majority. Given the small number of members, the Committee on Procedures further recommend that in the event of a tied vote, the chairperson should have a casting vote.

Recommendation 25

The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bill committees may exercise the powers in section 44(1) of the Northern Ireland Act.

Recommendation 26

The Committee on Procedures recommend that, prior to the introduction of the Assembly’s first private bill, detailed guidance for promoters and objectors be published by the Bill Office.

Introduction

Background

1. On 30 May 2007 the Committee on Procedures agreed to undertake an inquiry into procedures to enable the introduction of private legislation. The inquiry was to consider all the procedures relating to a bill such as: stages for private bills; fees; objections to a private bill; and private bill committee and hybrid bills.

2. The following terms of reference was agreed at a Committee meeting on 14 November 2007:

- gathering information on procedures for dealing with private legislation from other legislatures;

- considering and evaluating options for the procedures for private legislation in the Northern Ireland Assembly;

- consult with and make recommendations to the Northern Ireland Assembly Commission on a costing structure for private legislation; and

- reporting to the Northern Ireland Assembly making recommendations on a new set of Standing Orders on private legislation and associated costing structure.

3. The Committee agreed that the methodology for the inquiry should include:

- comparative research on how private bill procedures are dealt with in the other UK legislatures;

- oral evidence from a small number of well informed witnesses and written evidence from a number of other interested parties;

- best practice visits; and

- advice from various government departments.

The Committee’s Approach

4. A public notice was placed in the main provincial newspapers on 4 December 2007, inviting written evidence in respect of the Committee’s inquiry into private legislation.

5. In response to its call for evidence, the Committee received nine written submissions from the following organisations:

- The Scottish Parliament;

- House of Commons;

- Society of Parliamentary Agents;

- The National Trust;

- Derry City Council;

- The Law Society of Northern Ireland;

- The Equality Commission;

- Department of the Environment; and

- Department for Regional Development.

6. In addition to the above, the Committee sought advice from Assembly Legal Services and commissioned Assembly Research and Library Services to inform its initial considerations.

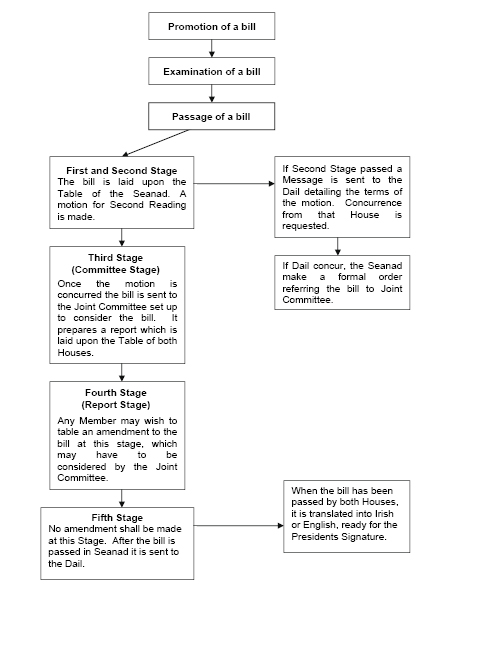

7. The Committee noted that its visit to the Irish Parliament on 6th February was particularly interesting and useful as parliamentary staff were able to illustrate procedures on private bills with reference to a number of actual bills.

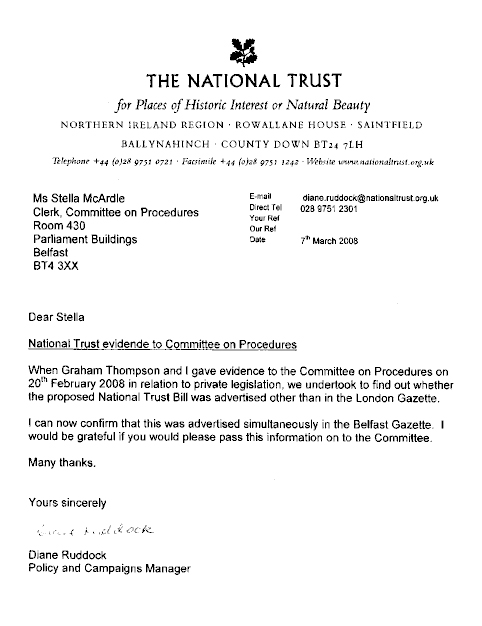

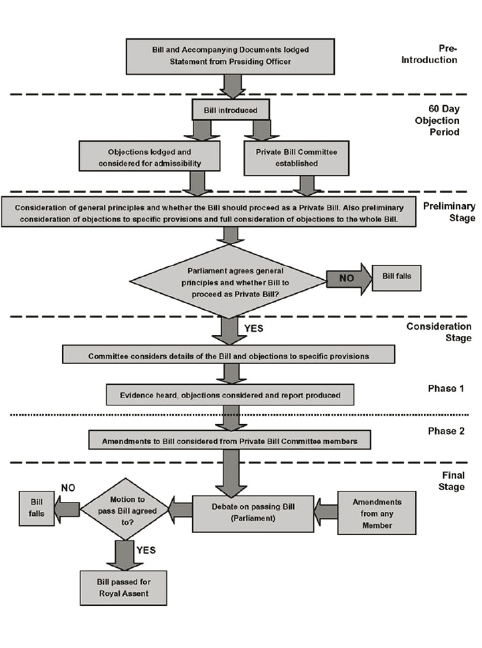

8. On 20 February 2008, the Committee took oral evidence from six organisations. The evidence from Westminster and the Scottish Parliament was particularly helpful in highlighting to the Committee that preliminary scrutiny can smooth the passage of a bill and that the test of appropriateness is best carried out at the preliminary stage. The representatives of the Society of Parliamentary Agents, London and The Law Society of Northern Ireland also concurred with this position. The evidence from the National Trust provided the Committee with an insight into the experience of taking a private bill through Westminster and Derry City Council expressed their views to the Committee of their considerations to a proposed private bill.

9. The Committee weighed up the issues arising from the evidence received from witnesses and carefully examined the procedures and practices involved with a private bill in other legislatures. The Committee’s consideration of these issues is covered separately in the report.

10. At its meeting on 8 October 2008, the Committee on Procedures agreed its report on Procedures on private bills and agreed that it would be printed.

Consideration of Key Issues

Background

11. The Assembly’s existing Standing Orders acknowledge the need for procedures to enable the introduction of private legislation. Standing Order 13(1) states that “Private Bills shall be subject to the same stages as those laid down for Public Bills and the procedure on such Bills shall be subject to such further requirements as from time to time are ordered by the Assembly.”

12. While no specific procedures exist at the moment for dealing with private legislation in the Northern Ireland Assembly, in 2008 the Committee on Procedures undertook an in-depth inquiry into possible procedures that may be adopted by the Assembly. This included a research exercise examining practices in other legislatures where private legislation is subject to significantly different procedures to those used for public bills. The inquiry also included good practice visits, calling for written submissions and the taking of evidence from a number of witnesses.

13. This report represents the policy position taken by the Committee on Procedures on private legislation and once agreed by the Northern Ireland Assembly the next step will be the preparation of new Standing Orders and the development by the Bill Office of detailed guidance to enable the Assembly (and the public) to deal with private legislation in a manner appropriate to its particular circumstances.

14. An examination of the history of private legislation in Northern Ireland has revealed that the circumstances leading to many of the bills presented to previous local legislatures are unlikely to recur in the future. This is mainly due to the fact that the expansion in the body of public law over the years has reduced the need for individuals and bodies to resort to private legislation. The Scottish Parliament has seen a number of private bills introduced since devolution, however, many of these have related to the need to provide non-departmental bodies (local authorities, transport companies) with vesting and other powers necessary for major transport and works projects to be carried out. The situation in Northern Ireland is different and such projects are subject to normal planning inquiries, with vesting and other essential powers exercised by the responsible government departments. The scope for private legislation is, therefore, quite limited and in the main is likely to involve bills related to the legislative arrangements for (particularly the constitutional arrangements of and endowments to) charities, colleges or churches, matters related to the powers of local authorities and in the general area of company law. In the course of undertaking this inquiry advice was sought from the various departments regarding the likelihood of a “works” type private bill being introduced to facilitate the construction of a light railway or other form of rapid transit system and on the likelihood of a local authority taking a private bill. The response received from Department of the Environment (DoE) indicated that under the current Northern Ireland system of local authorities, there was little likelihood of such a bill in the foreseeable future. The response from Department for Regional Development (DRD) (the Department most closely involved with transport projects) indicated that should such a need arise in the future, the Department would sponsor it through a public bill.

15. In 2007 the National Trust introduced, in Westminster, a private bill related to its governance structures in Northern Ireland. This private bill would have come to the Assembly had it been restored at that time. Additionally, Derry City Council quite recently investigated the possibility of private legislation to release the Council from the effects of a restrictive trust on use of its land. These examples are sufficient to demonstrate that a private bill could be presented to the Assembly at any time.

16. In devising procedures for private legislation, the Committee inquired into a number of key topics or issues including:

- the stages for private bills;

- the committee stage including committee membership, procedures and the ability of a private bill committee to amend a private bill in committee;

- how objections to private bills should be received and dealt with; and

- fees associated with private bills.

Proposed Assembly stages for private bills

Preliminary scrutiny

17. Public bills introduced by the Executive have normally been subject to public consultation and the relevant Assembly committee will in general have been kept informed and been involved in the drafting of the policy objectives. This ensures that Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) on the whole have a good knowledge and understanding of the proposed public bill and its policy objectives. However, this may not be the case with private bills. While pre introductory scrutiny is the norm for executive public bills, research showed that in many other legislatures, MLAs may only become aware of a private bill when it is introduced. Therefore, in common with both procedures at Westminster and the Scottish and Irish Parliaments, the Committee deliberated on a unique set of preliminary scrutiny procedures for private bills. The aim of this phase is to ensure that private bills will satisfy the statutory requirements pertaining to legislation in Northern Ireland as well as meet criteria that the Committee feel are important to safeguard public interests. Evidence from the Scottish Parliament also suggests that preliminary scrutiny can smooth the passage of a bill:

“This pre introduction scrutiny, which is very time consuming, did reduce the number of formal amendments required and I am also fairly sure it also reduced the number of objections received to these later bills”

Written evidence on private bill procedures, Scottish Parliament.

18. When investigating pre introduction criteria the Committee focused on a number of issues including whether the bill is appropriate as a private bill.

19. The Committee on Procedures, having agreed that a preliminary scrutiny was desirable, explored when it should take place, who should undertake it and what it should cover to decide whether it is appropriate to be introduced. Appropriateness is defined by the Committee as proof of need, no alternative methods, and appropriate subject matter. In the Scottish Parliament the task of assessing whether the bill is appropriate to proceed as a private bill is carried out by a private bill committee at Preliminary Stage. This situation is different in the UK Parliament:

“In the UK Parliament, there is no intervening stage between introduction and second reading, or indeed between second reading and committee stage. If there are questions about whether the subject matter of a private bill is appropriate, then the Speaker of the House of Commons can draw this to the attention of the bill to the House on its second reading. Although this has not happened for a number of years... such issues may arise for example if a private bill contains matters which would more appropriately be dealt with as a matter of public policy in a Public bill. The Speaker would normally take advice from his counsel on issues such as this....

The fact is that there have been no recent cases in the UK Parliament and none in the Scottish Parliament where a private bill has not been allowed to proceed because the subject matter is inappropriate for a private bill. That is not to say that it would not happen again, but it would be fair to say that promoters of private legislation realise that it is important to ensure that they have taken advice on the issue first.”

Written evidence, Society of Parliament Agent.

20. Advice received in written evidence from the Clerk of Bills in the House of Commons also indicated that the test of appropriateness is better carried out at pre introductory stage:

“Any test of appropriateness would be better carried out at the pre introduction stage, with the responsible Assembly officer forming a view on the basis of legal advice and precedent and, if necessary, making a recommendation for a ruling to the Speaker.”

Written evidence from the Law Society of Northern Ireland also concurred with this position and indicated that preliminary requirements for a private bill should include evidence that the bill is exclusively private in content and is the most appropriate mechanism available to meet the needs of the promoter.

21. Based on the evidence provided to it and on the desire of the Committee that parliamentary time should not be wasted, the Committee on Procedures recommend that private bills should undergo a preliminary scrutiny before they are introduced to the Assembly and that the tests for the appropriateness of a private bill should be carried out at pre introductory stage.

22. The Committee do not feel it is fitting that a private bill should be allowed to be introduced if it is not appropriate. To do so would represent a waste of time and resources for the promoter, the objectors and the Parliament.

23. Another area which the Committee focused on for preliminary scrutiny was that of consultation by the promoter with those likely to be affected. Research and oral and written evidence presented to the Committee by Westminster and the Scottish Parliament indicated that early engagement by the promoter with those affected by the provisions of the private bill can help to ensure that many concerns are addressed and accommodated before introduction. This in turn leads to a smoother passage and minimises the resource implications as well as reducing the number of formal amendments.

24. The Committee did consider formalising a specific consultation process into Standing Orders on private bills. However, it noted that good practice in consultation methodology changed constantly and agreed that rather than have a specific Standing Order in this area, which may quickly become dated, Standing Orders should indicate that the promoter would be expected to undertake a consultation commensurate with current good practice and with the specifics of the bill.

25. In coming to this recommendation the Committee discussed with Ms Ruddock and Mr Thompson of the National Trust Northern Ireland, the consultation undertaken by that organisation when it took a private bill through Westminster procedures.

26. The Committee observed that the consultation was totally compliant with Westminster Standing Orders. However, that compliance meant that it was only advertised in the London and Belfast Gazette. The Committee did not believe that this, in Northern Ireland terms, represented good practice consultation although it did note that the National Trust did contact all Northern Ireland Members of Parliament (MPs) and did consult with the Department of Social Development.

27. The Committee also examined other criteria for preliminary scrutiny such as ensuring that the promoter provides all relevant documentation, demonstration that an organisation seeking the private bill has the support of its members, that it meets Assembly drafting requirements and complies with section 6 of the Northern Ireland Act and is accompanied by a fee (see paragraphs 84-90 for information on fees).

28. The Committee discussed in detail whether this preliminary scrutiny should be carried out by an Assembly committee or by an official. It noted that in general the preliminary scrutiny is largely formal and procedural in nature and that therefore, it would be adequate for it to be carried out by an official who would provide a report to the Speaker. This report would also be made available to the private bill committee.

29. The Committee recommend that an official of the Assembly (to be known as the Examiner of Private Bills) should undertake a preliminary scrutiny of the bill with a view to reporting to the Speaker on whether it meets the special requirements for private bills as laid down in Standing Orders.

30. The Committee recommend that the promoter must be able to demonstrate to the Examiner of Private Bills that the bill meets a number of criteria before being eligible for introduction. These criteria should include:

a. that there is “proof of need”. In other words, the promoter has proven that there is a real need for the legislative exemption, power or amendment being sought;

b. that alternatives to the promotion of a private bill have been sought and investigated. An explanation should be provided detailing why alternatives to a private bill are not suitable;

c. that the explanatory and financial memoranda are available and are in order;

d. that comprehensive statements are provided on areas such as the policy objectives and the consultation undertaken etc. The promoter will be expected to demonstrate that they have taken all reasonable steps to draw the bill provisions to the attention of those individuals and bodies who will be affected and in particular, those who will be adversely affected. The promoter should, for example, place public notices in the regional papers and relevant local papers and undertake other appropriate forms of consultation concurrent with good practice. The promoter will be expected to provide in the statement to the Examiner, the names and addresses of those whom they have identified as potentially being affected by provisions of or the entirety of the bill. They should also provide detailed information to those affected on how they can object to the bill using parliamentary procedures. The promoter will be expected to demonstrate in the statement, that they have engaged with those affected at an early stage and to demonstrate that they have attempted to address as many concerns and objections as possible before the bill is formally introduced;

e. that all relevant documents such as maps and diagrams are provided;

f. that proof has been provided that where an organisation is seeking the private bill, a resolution has been passed approving the promotion of the bill. The promoter must be able to demonstrate that this resolution is in accordance with the internal procedures of the organisation. Additionally, the promoter must demonstrate that the resolution has the support of 75% of the members of the organisation who voted. In exceptional circumstances the promoter may, in writing request an exemption to this requirement. The request must clearly lay out the reasons for the setting aside of the Standing Order and will subsequently be scrutinised by the Committee on Procedures. The Committee on Procedures will make a decision on whether to allow for the Standing Order to be set aside and that decision will be final;

g. that the private bill meets the layout and drafting requirements of the Northern Ireland Assembly;

h. that a comprehensive and reasoned statement has been provided which demonstrates how the proposed bill complies with section 6 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and that the consent of the Secretary of State has been given for the inclusion of any provision which deals with excepted or reserved matters;

i. that the private bill does not have any provision that will have the effect of authorising sums to be paid out of the Consolidated Fund; and

j. that the private bill promoter has provided contact details, that the private bill has been signed and dated and that it is accompanied by the fee.

31. The Examiner of Private Bills may enter into discussions at an early stage to assist the promoter in ensuring that they are able to meet the above list of requirements. However, the Committee does not believe that the Assembly should be proactive in this aspect and noted the following evidence from Mr Alan Sandall, Acting Clerk of Bills in the House of Commons:

“...it is always the responsibility of the promoter to make the case for their bills. They must prove that, as far as the public interest is concerned, the project for which authorisation is sought is a good idea and cannot be authorised by any means other than parliamentary authority.”

Stages for private legislation

32. In its consideration of the stages that a private bill should pass through, the Committee examined in detail, both through research and through oral and written evidence the procedures in place in the Scottish Parliament and in Westminster. The Committee examined the five stages operated by both the House of Commons and House of Lords and the four stages operated by the Scottish Parliament. It also considered the stages in place for public bills in the Assembly. After due consideration the Committee recommend that the stages for private bills should, as far as possible, reflect those in place for public bills for the Assembly. The Committee noted that in following established Assembly procedure, private bills in Northern Ireland would have additional stages over and above those in place in other legislatures. However, MLAs have a degree of familiarity with the stages for public bills. As private bills are expected to be few and far between, the familiarity of the stages should assist towards a smooth passage.

33. While the recommendation is that the stages for a private bill remain as per those for public bills, the Committee also recommend differences in the amount of time between the stages and in the role of the private bill committee. The Committee consideration of the differences is discussed in the following paragraphs.

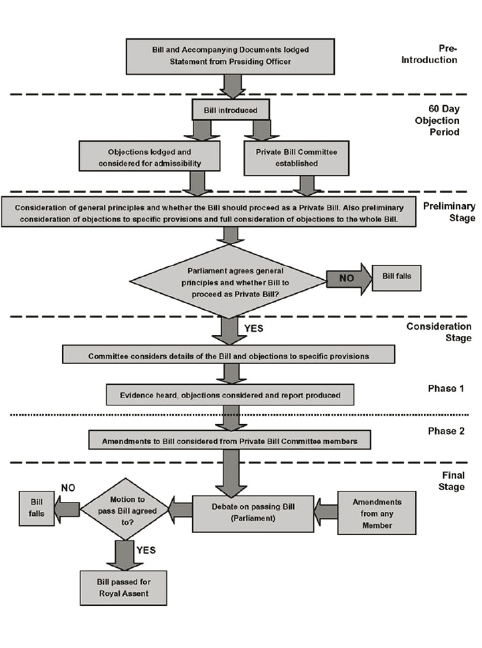

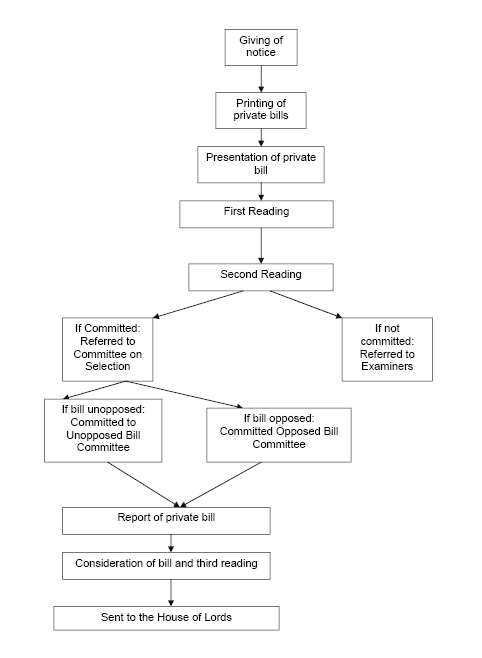

34. A diagram at page 23 summarises the stages recommended by the Committee.

Introduction (First Stage)

35. The Committee considered the issue of the introduction of a private bill noting that public bills are introduced by a Minister or a MLA. It noted that in the UK Parliament a private bill is founded on the basis of a petition to the Crown. Westminster Standing Orders state that petitions for private bills (with copies of the bill attached) must be deposited on or before 27th November. The bill then undergoes examination for compliance with Standing Orders and is presented to the House on 21st January (or first sitting day thereafter). Since 1945 it is no longer necessary for a Member to present bills – private bills are presented by the Clerk of the House.

36. Standing Orders of the Scottish Parliament do not require a Minister or member to introduce a private bill. In Scotland a private bill is introduced by the promoter by being lodged with the Clerk on any sitting day.

37. The Committee on Procedures recommend that the introduction of a private bill will be an announcement by the Speaker that a private bill has been received and will now be published. The Speaker will not normally introduce a private bill until receipt of the preliminary examination report from the Examiner of Private Bills. The Speaker will announce that the Business Committee has agreed to establish a private bill committee and the names of the Members who will serve on the private bill committee.

38. Notice of the formal introduction of a private bill will be published in the Assembly’s Weekly Information Bulletin.

Period between first and second stage

39. The Committee recommend that there should be a minimum of 60 working days between first and second stage. In coming to this recommendation, the Committee took note of a number of factors. The first factor to be considered was the lodgement of objections. The Committee spent considerable time discussing the lodging of objections and was particularly concerned that the objector was provided with sufficient time to prepare objections to the bill. The Committee deliberated on procedures in other legislatures and considered that 42 working days was sufficient for the lodgement of objections. This then allowed 18 working days for consideration of objections against a set of criteria discussed in paragraphs 99-100.

40. Another factor which contributed to the recommendation for a minimum of 60 working days between first and second stage was that unlike public bills promoted by Ministers, committees or individual MLAs, the Assembly is likely to have no prior knowledge of a private bill or its legislative objectives. The Committee agreed that it would be appropriate to allow 60 working days to elapse to ensure that MLAs have sufficient time to consider the provisions of a bill before the second stage debate on its principles.

41. The Committee on Procedures considered that in coming to conclusions on the principles of a private bill, it is likely that the private bill committee would normally only seek written evidence. However, there may be occasions when a private bill committee feel it is necessary to seek oral evidence. In such a situation, the private bill committee should ensure that oral evidence is restricted to the principles of the bill and does not stray into matters which should be dealt with at Committee Stage. The taking of oral evidence should be conducted as per normal Assembly committee procedures.

42. In order to assist the Assembly in its consideration of the principles of the bill at second stage, the Committee recommend that the private bill committee established at first stage should report to the Assembly on the principles of the bill and invite, receive, assess and allow or disallow objections.

43. The Committee came to this recommendation after lengthy discussion. There was agreement that as it was unlikely that individual MLAs would have the time to consider the principles of the bill in-depth, a workable and practical option would be to require the private bill committee to carry out this task and report to the Assembly at the second stage debate. Likewise, requiring the private bill committee to take responsibility for the receipt, assessment and allowing or disallowing the objections would also be a workable and practical option.

44. During the 60 working day period between first and second stage, the private bill committee would be able to call for additional information from the promoter, if required, seek advice from the Assembly Legal Services and appoint specialist or technical advisors if required. Specialist or technical advisors may be appointed to assist the Committee in the assessment of objections and other tasks although the Committee agreed that the private bill committee would not normally seek oral evidence or enter into correspondence with objectors at this stage. The private bill committee would also publish in the Assembly Weekly Information Bulletin a list of objections received and whether they were allowed or disallowed indicating whether the allowed objections were to the whole bill (an objection to the principles of the bill) or to part of the bill. Objectors whose objections have been admitted would be allowed, at committee stage, to come before the private bill committee and present their case.

Second Stage

45. Second Stage of a private bill will be a minimum of 60 working days after Introduction Stage.

46. The Second Stage of the private bill is a debate to approve the principles of the bill. As with public bills, it is proposed that the Second Stage of a private bill will be moved on a date determined by the Business Committee following the expiry of the period stipulated in Standing Orders (60 working days).

47. During the debate, the chairperson of the private bill committee will outline the main features of the bill. The report produced by the private bill committee between Introduction and Second Stage will inform members and enable detailed consideration of the principles of the bill. The Assembly will vote and the bill will either pass Second Stage or will fall. Voting will be by simple majority. As with the procedures for public bills, debate will be limited to the principles of the bill.

48. The private bill, on passing its Second Stage, will be referred to the private bill committee for its committee stage.

Committee Stage

49. The Committee Stage of a private bill will commence immediately after the Second Stage. The private bill committee shall have 30 working days from the date of referral (excluding any periods when the Assembly is adjourned for more than three working days) to consider and report on the private bill. The private bill committee may, in the name of the chairperson, table a motion to the Assembly to extend the 30 working days to a date specified in the motion.

50. In line with both the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament, the Committee recommend that both the promoter and the objectors be allowed to present their case to the private bill committee, are able to call witnesses to support their evidence, that the promoter and objector be allowed to cross examine one another under the direction of the committee and be allowed legal representation. The rationale for recommending this type of quasi judicial setting is that the private bill committee will be primarily concerned with fact finding and adjudication between the promoter and the objector. The work of a statutory committee is mainly about scrutiny of policy. However, the experience in Scotland, the UK Parliament and the Irish Parliament is that private bill committees will focus on hearing evidence that is factual, intricate and very detailed to enable them to establish fundamental often complex details of a factual nature that can be of a competing nature.

51. Individuals and bodies who have made objections do so because they will be directly and adversely affected by the provisions of the bill. In order to sustain their arguments and present supporting evidence it may be necessary for each party to present their case and call witnesses. It will be the role of the private bill committee to hear the evidence and decide in favour of one party or the other. Evidence presented to the Committee on Procedures from witnesses underlined the importance of allowing legal representation and cross examination. Written evidence from the Law Society Northern Ireland notes:

“Legal representation would assist the promoter and objector(s) in articulating their arguments and ensure the evidence that they present is clear and succinct. Furthermore for members of the general public wishing to object, the prospect of appearing before an Assembly Committee may be daunting. To deny objector(s) the assistance of legal representation might therefore deter their participation in the legislative process.”

And later

“It is recommended that the objectors and promoters be afforded the right to cross-examine one another. Cross-examination is an important mechanism for testing evidence and affords the opposing party the ability to challenge any statement of fact in dispute”

52. The Committee on Procedures gave detailed thought to the aspect of cross examination and legal representation particularly around the issue of management within the private bill committee and the issue of “equality of arms” for objectors who may not be able to afford legal representation.

53. In Scotland, private bill committees have the option of hearing the evidence or appointing an Assessor to hear the evidence on its behalf. This is designed to“reduce the burden on Members of the Scottish Parliament in dealing with what are at times highly complex and technical matters”[1]. The introduction of Assessors in the Scottish Parliament arose largely because many of the private bills were highly technical in nature involving issues such as noise levels and land acquisition through compulsory purchasing. Evidence suggests that it is unlikely that such technical private bills will come to the Assembly.

54. The Committee are not making any recommendation on the involvement of Assembly Legal Services in the cross examination again leaving it up to the discretion of the private bill committee who will decide, based on the specifics of the private bill, whether the promoter and objectors can undertake the cross examination under the direction of the chairperson or whether this is better done with assistance from the Assembly Legal Services.

55. The Committee on Procedures were particularly concerned about the issue of “equality of arms” between promoters and objectors given that objectors are likely to be less well resourced and self confident than the promoter. Examples from other legislatures indicated that objectors, due to lack of resources, often do not have legal representation. Some initial thought was given to the possibility of providing the objector with resources for legal representation but this was quickly ruled out. It is not the role or the responsibility of the Assembly to fund legal representation for objectors and it would be unfair to expect the promoter to pick up such costs. Additionally the Committee was reassured by evidence from other legislatures that the chairperson and members of a private bill committee have been remarkably understanding of this issue and strive to put the objector at ease as well as reassuring them that views will be treated with the same level of seriousness as the promoter. The promoter also understands that the members of a private bill committee will not tolerate hostile cross examination. Mr Sandall in oral evidence to the Committee noted:

“However, we are concerned that private individuals who may not be as well resourced as the promoters of private Bills should have every opportunity to bring their concerns to the attention of the Committee on the Bill. We keep the fees for petitions against a Bill unrealistically low. Objectors are not required to employ a full-time parliamentary agent or a solicitor to act on their behalf. They can act on their own behalf, and in doing so they will have the full assistance and co-operation of the clerks in the Private Bill Office in preparing their case, although we cannot do the basic work for them. We cannot advise on tactics, but we give as much assistance and advice to them as we properly can, within the rules of fairness. A Committee composed of Back-Bench MPs, who are well aware of the position of the small man, will bend over backwards to ensure that an objector is given every opportunity to express his own case and to call into question the promoter’s case.”

56. The Committee also noted the procedure used by Scotland whereby full written disclosure of all evidence in advance is required and that no deviation from the terms of the written evidence was permitted. This procedure, while assisting both the objector and promoter, also ensured that the objector could be as well prepared as possible.

57. The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bill committees should have the power to amend a bill in committee. This is a considerable departure from the practice of the Assembly and has been taken because the role of the private bill committee, as outlined above is substantially different from that of a statutory committee.

58. During the Committee Stage, one of the main roles of the private bill committee is to arbitrate between the interests of the promoter and the objector and in doing so it acts in a quasi judicial capacity. The private bill committee has the responsibility to decide between conflicting claims of private interest. Because of the factual and detailed nature of the bill only the members of the private bill committee are able to consult directly with the promoter and objector on the effects of any proposed amendment. Only the private bill committee has therefore had the opportunity to hear all the evidence and is therefore best placed to make amendments directly to the bill.

59. In the Assembly the majority of amendments to any public bill are normally formulated at Committee Stage. In Assembly statutory committees, the committee make recommendations which go to the Assembly for debate and vote during the Consideration Stage debate. The Minister or member in charge of the bill has ample opportunity to state his or her position on the proposed amendment during the debate while the chairperson and members of the statutory committee are able to defend the amendment and state their position. This procedure can not be duplicated for private bills. Participation in Assembly debate is restricted to elected members and there is no opportunity for the promoter or objector to defend their position. That can only be done in the committee and that is therefore the best place for the bulk of amendments to be made.

60. Amendments will be made after the private bill committee has heard from both the promoter and objector and other interested parties during the clause by clause scrutiny of the bill. In line with established parliamentary practice both in the Assembly, Scotland and at Westminster, the Committee do not foresee that the private bill committee would accept amendments which are beyond the scope of the bill. A private bill committee should also not enlarge the powers sought by the bill as such an amendment may affect individuals and bodies not initially affected and who have not therefore had the opportunity to lodge an objection.

61. On occasion, the promoter may wish to add a new provision or new clause to the private bill. In Westminster this is known as “additional provisions”. Such provisions must be deposited by the promoter before the private bill committee meets at Committee Stage and are subject to the approval of the Speaker and the chairperson of the committee. The Committee on Procedures proposes that when the Speaker and the chairperson have agreed to allow additional provisions, they will be subject to:

- the same preliminary scrutiny as the rest of the private bill;

- the approval of the Assembly to the principles of the additional provisions (reopened second stage); and

- the Committee Stage will not commence for the entirety of the bill until an additional 60 days has been allowed for objections to the additional provisions.

62. In its consideration of evidence, a private bill committee can call its own witnesses and should take the views of the relevant government department i.e. a committee considering a private bill relating to a charity will want to take the views of the relevant government departments.

63. The private bill committee will produce a report to assist the Assembly at Consideration Stage.

64. The opportunity for all MLAs to make amendments to the bill will be provided at Consideration Stage.

Committee Stage where no objections have been received

65. Where no objections have been received, the Committee recommend that the private bill be referred to a private bill committee. Private bills ask for an exemption from or amendment to general law. However, many private bills in Westminster are unopposed and in such instances, the role of the Northern Ireland private bill committee will be to assure itself that the bill does not act against government policy and that the interests of the public are safeguarded and that the bill only goes as far as necessary.

“Its proceedings are briefer and less formal than those of a committee on an opposed private bill; but, because there are no opponents of the bill, a special responsibility rests on the committee in its consideration of the preamble and provisions of the bill to ensure that the interests of the public are properly safeguarded ...” Erskine May 23rd Edition, page 1032

66. The promoter will be called to present their case and may call witnesses if they so desire. The private bill Committee will adopt an inquisitional approach; ask questions of the promoter and witnesses and after collecting the evidence may make amendments to the bill.

Consideration Stage

67. The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Consideration Stage of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill. There will be a minimum of five working days between the completion of the Committee Stage and the Consideration Stage.

68. Any MLA may propose an amendment at Consideration Stage under the same conditions as apply to a public bill. For example currently amendments to public bills must be tabled by 4.30pm on the Thursday before the Consideration Stage and are listed on the Marshalled List. Amendments to private bills would be subject to the same procedures. However, where there are a significant number of amendments proposed and/or the amendments are substantive or technically complicated, the Assembly, on a motion, may decide to ask the private bill committee to meet again to consider them and produce a report to aid the Assembly. Standing Orders will allow that such a motion may be tabled by the chairperson of the private bill committee by 9.30am on the day of the debate at Consideration Stage and will ask for an adjournment of Consideration Stage to a time to be decided by the Business Committee who shall consult with the private bill committee. The chairperson should consult with the committee members on such a motion and the motion should state which amendments are being referred to the private bill committee. The motion can not be amended or debated.

69. Where a private bill has been referred back to the committee for consideration of amendments, the private bill committee may make amendments in committee.

70. A mechanism to refer the private bill back to the committee is necessary because some of the proposed amendments may have consequences to existing objectors or indeed affect a new set of people who have not had an opportunity to object. It will also allow the promoter to consider and discuss with the private bill committee the consequences to them of any proposed significant amendments. In addition, such amendments may require consequential changes elsewhere in the bill.

71. The chairperson of the private bill committee will move and wind the debate.

Further Consideration Stage

72. The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Further Consideration Stage of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill. There will be a minimum of five working days between Consideration Stage and Further Consideration Stage.

73. Further Consideration Stage will be a final opportunity to debate and vote on amendments. This stage will allow for corrective (technical or editorial) amendments only to be made to ensure that the bill worked as intended. Where no amendments have been selected the Assembly will be advised that the private bill stands referred to the Speaker. The chairperson of the private bill committee will move and wind the debate.

Final Stage, Reconsideration Stage and Royal Assent

74. These stages will follow existing practice for public legislation with the chairperson of the private bill committee moving the Final Stage and winding the debate.

75. The Committee on Procedures recommend that the Final Stage, Reconsideration Stage and Royal Assent of a private bill should follow the procedures and protocols for a public bill.

Accelerated passage

76. The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bills should not be subject to the Standing Order which provides for accelerated passage.

Scheduling requirements

77. The Committee on Procedures recommend that where a bill has not completed its passage by the end of an Assembly session it shall be carried forth and its passage continued into the next session.

78. The Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill shall not be carried forth if the Assembly stands dissolved or is suspended. Where a private bill falls because of dissolution or suspension of the Assembly, it may be introduced no sooner than a minimum of 10 working days after the first sitting of the Assembly in the new mandate. If the bill is reintroduced on the exact same terms, the promoter will not be expected to pay a second fee. Objections may also be re-lodged on the exact same terms without payment of fees. Private bills and objections reintroduced on the exact same terms after dissolution or suspension may be expected to pay any top up fees associated with increased charges for the promotion or objection of a private bill. Private bills and objections that have been altered will be expected to pay the agreed fee. In the event of suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the promoter and objector may be entitled to part repayment of fees paid.

Parliamentary Agents

79. The Committee noted that the Westminster Standing Orders on private bills state that the promoter of a private bill must use “Roll A parliamentary agents” but that it is not the case in either Scotland or the Republic of Ireland. To comply with Standing Orders in Westminster, promoters must use Roll A parliamentary agents to promote the private bill and they are responsible for ensuring its compliance with Standing Orders and its passage through either the House of Commons or House of Lords. The Committee noted that the Standing Orders in Westminster are detailed, complex and long standing having initially been devised at a time when the majority of legislation was private. In such circumstances, it makes sense to entrust the drafting and passage of private legislation to companies with expertise and experience.

80. The Committee was particularly interested in the experience of those who had used parliamentary agents and welcomed the oral and written evidence provided by Derry City Council and the National Trust Northern Ireland, both of whom had experience with using parliamentary agents for private legislation. Mr McMahon from Derry City Council noted the following in relation to possible local government private bills:

“Inevitably, the promoter of a local bill would seek legal advice anyway, and parliamentary agents are nothing more than specialised lawyers. Why not go to a specialist lawyer? If you have a legal issue with anything, you want to go to a lawyer who has specialist expertise.”

Mr Thompson from the National Trust remarked in oral evidence to the Committee:

“Drafting Bills is a specialised skill. Parliamentary agents are all lawyers anyway. I know from personal experience that attempts at drafting Bills by people who are not adept at that skill usually leads to bad legislation — if it ever gets that far.”

81. The Committee also noted with interest the views of the Law Society Northern Ireland as expressed by Mr Eakin. In evidence to the Committee, Mr Eakin noted that the expertise in private legislation is not available locally and in such circumstances, “...the use of parliamentary agents is an appropriate and probably invariable, way of proceeding in such matters.” However, Mr Eakin further noted that the Law Society did want local firms, over a period of time to gain expertise and be able to work as recognised parliamentary agents.

82. The Committee considered whether the Standing Orders of the Assembly should insist on the use by the promoter of parliamentary agents. It noted that the in-depth experience and familiarity with the details of procedures could assist in smoothing the passage of a bill. Legislation which is drafted incorrectly may have to go back and forth for correction resulting in a clogging of the system. It further noted the situation in Scotland where there is no requirement to use a parliamentary agent but invariably promoters seem to consistently use parliamentary agents. The Irish Parliament also does not include in Standing Orders a requirement to use parliamentary agents but instead requires that the bill is drafted by a solicitor of at least three years standing.

83. The Committee agreed not to set any constraints on who can act for the promoter of a private bill but strongly suggest that promoters ensure that the draftsperson responsible for the drafting of the bill has detailed and extensive knowledge of drafting legislation, of the laws of Northern Ireland and the legal and drafting conventions of the Assembly.

Fees and other costs for the promoter of the private bill

84. Research showed that all other legislatures charge a fee payable by the promoter for the passage of a private bill and the Committee on Procedures believe that it is reasonable that the promoter of a private bill should meet from their own resources all costs incurred directly by them (e.g. the cost incurred in having a bill drafted by legislative draftspersons).

85. Private bills by their nature deal with private interests affecting a relatively small number of individuals or bodies. The Committee on Procedures do not consider therefore that the administration costs associated with the passage of a private bill through the Assembly should be borne by the Assembly which is funded from the public purse.

86. The Committee on Procedures recommend that it will be appropriate for the Assembly Commission to apply a fee of £5,000.00 to the promoter of a private bill to cover the administration costs that will arise from the Assembly Stages of the bill. The Commission may wish to revisit the fee charged at the beginning of each mandate.

87. The cost of printing documents (including the bill itself, the Explanatory and Financial Memorandum and other documents, such as the Report on the Committee Stage) plus all other associated incidentals such as broadcasting of the private bill meetings and room hire if the private bill committee undertake a site visit will also be charged at cost to the promoter.

88. The Commission is not empowered to levy a fee in respect of the time spent by Assembly members on a private bill.

89. The Committee on Procedures also give consideration to the application of a reduced fee in certain cases, e.g. for bills introduced by organisations whose charitable status has been formally established and recommend that fees for charitable religious and educational organisations and for literary or scientific purposes from which no private profit or advantage is derived be reduced by 75%.

90. Any sums received by the Assembly Commission from the application of fees associated with private bills will be payable to the Consolidated Fund.

Objections to a private bill

91. Based on a review of procedure in other legislatures the Committee on Procedures proposed that individuals or organisations should be able to register objections with the Assembly as soon as a private bill has been introduced and that the cut off date for receipt of applications will be 5.00pm on the 42nd working day after the date of introduction of the private bill.

92. In coming to this decision the Committee considered the period of time in Westminster (64 to 71 days) and in Scotland (60 days). While the period of time recommended is shorter in Northern Ireland, the Committee believe it is adequate especially as the private bill committee will have the discretion to allow a late objection in certain circumstances i.e. from an individual who missed the closing day because they were not aware of the private bill due to circumstances such as an extended hospital stay or period abroad.

93. The Committee recommend that late objections will be allowed in special circumstances. A late objection will only be admitted at the discretion of the private bill committee and should be accompanied by an explanation for the late submission and should show that the objection was lodged as soon as reasonably practicable. Late objections must meet the criteria set out for objections set out below and be lodged before the first meeting of the private bill committee at Committee Stage.

94. The Committee also considered and agreed that a lodged objection may be withdrawn at any time. A lodged objection may be altered within the 42 working day period.

95. All objections should be addressed to the clerk of the private bill committee, Parliament Buildings, Stormont Estate, Belfast BT4 3XX. Objections may be posted (recorded or registered post is recommended) or hand delivered. Non-written objections will only be accepted in exceptional circumstances. An acknowledgement of receipt of objection will be posted to the objector. Email versions of the objections are acceptable and encouraged so long as a signed hard copy of the email version is received within the 42 working days along with the fee.

96. The private bill committee will assess and allow or disallow all objections. In coming to a decision, the private bill committee may ask for additional information from the objector and this should be provided within the timescale requested by the committee. The private bill committee may delegate the administration of this task to the Examiner of Private Bills or to a specialist advisor but the final decision on admission will rest with the private bill committee.

97. The clerk to the private bill committee will inform the objector in writing of whether the objection has been deemed admissible or not.

98. After the period for objections has expired, the private bill committee will publish in the Weekly Information Bulletin, a list of the names of all objections lodged and whether they have been deemed admissible or otherwise.

Criteria for objections

99. In examining and making recommendations for the criteria for objections to private bills the Committee observed that the primary criteria should be that objectors be able to demonstrate a legitimate interest in the bill and would be directly affected by its provisions. As noted in evidence to the Committee by the Society of Parliamentary Agents, this is “...consistent with the nature of a private bill, which affects particular persons and areas and not the public at large.” The Committee did not agree to the standing of an objector being challenged by the promoter – it believes that the task of assessing whether an objection should be allowed or not should remain entirely in the hands of the private bill committee.

100. The Committee on Procedures therefore recommend a list of criteria for an objection to a private bill as detailed below:

- the nature of the objection should be clearly set out i.e. why the objector opposes the bill;

- the objection must state if it is to the bill as a whole or to part of the bill. If the objection is to part of a bill, the part(s) must be clearly identified by reference to particular sections;

- the objection must demonstrate how the interests of the objector are adversely and directly affected i.e. loss of earnings, reduction in property value, loss of amenity etc; and

- the objection must be legible, signed, dated and provide the objectors name, address and contact details (telephone, email and fax). The objection should be accompanied by the full fee.

Fees for Objections

101. The Committee spent considerable time debating the fees which it will recommend the Commission should set for the lodging of objections. While some members stated that they did not wish to set fees, other members did believe that the Assembly should recoup some of the costs associated with the administration and assessment of objections and deter frivolous objections. The Committee concluded that a fee of £20.00 would be sufficient to obtain these aims.

102. In line with procedures in other legislatures, the Committee agreed that groups of individuals and bodies, with similar objections would be encouraged to come together and lodge one objection covering all the grounds of their objections and be charged only one fee.

103. The Committee also agreed that an individual or body could use one objection to cover more than one set of objections.

104. The Committee recommend to the Northern Ireland Assembly Commission that the fee for an objection be set at £20.00 and in the event of a withdrawal of the objection, is non refundable.

Private bill committee

105. The Committee on Procedures examined the structures of private bill committees in other legislatures particularly with regards to membership and procedures. The Committee noted that in Scotland five Members of the Scottish Parlaiment are required to form a private bill committee and that in Westminster four members are required. A Committee of four or five would be smaller than most Assembly committees; nevertheless the Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill committee in the Assembly has a membership of five appointed by motion from the Business Committee. This number is based on the rationale of the different role of a private bill committee compared to an Assembly statutory committee. The role of the members in a private bill committee is to be neutral and to adjudicate between conflicting private interests – the political considerations and information which members bring to a statutory committee are of lesser importance. Five members are, in the opinion of the Committee on Procedures, adequate to carry out this role.

106. The Committee on Procedures noted that there is a detailed set of rules set out in the Scottish Standing Orders detailing which Members of the Scottish Parliament can and can not sit on a private bill committee. Oral evidence from Mr David Cullum of the Scottish Parliament notes –

“The Committees established early on that they were arbiters in the process and did not act as advocates for the promoter or for the objector.”

And later

“Our Committees act quasi-judicially and must therefore suspend political considerations when considering a Bill and the objections to provisions in it. We had some interesting discussions at the outset with Committees explaining that process. That neutral role was especially important when it came to amending a Bill, whether in Committee or in the Chamber ...”

107. In line with the quasi-judicial and neutral role of members on a private bill committee, the Standing Orders for the Scottish Parliament have detailed rules on eligibility of a member to serve on a private bill committee. For example, a member is not eligible if he or she resides in or represents the area affected by the bill.

108. Westminster has similar provision with MPs with a constituency interest in a private bill debarred from serving on the committee scrutinising it. Erskine May states:

“Each Member of a committee on an opposed private bill, before he is entitled to attend and vote, is required to sign a declaration that his constituents have no local interest, and that he has no personal interest, in the bill...” Erskine May Parliamentary Practice, 23rd Edition

109. The Committee on Procedures noted that the quasi judicial nature of a private bill committee makes it important that the members recommended for appointment by the Business Committee are neutral and impartial. Therefore, prior to appointment to a private bill committee, prospective appointees will be asked to submit an up-to-date record of their interests. Specifically, they will be asked to consider the proposed bill and to declare:

- any past or present financial interests or material benefit related to the provisions of the bill which might reasonably be thought by others to influence their actions in their role as a member of the private bill committee; and/or

- any future financial interests or material benefit the member is expecting which is related to the provisions of the bill and which might reasonably be thought by others to influence their actions in their role as a member of the private bill committee.

110. The Business Committee should not recommend an appointment if based on the declaration of the Member:

- their principal place of residence is within an area / constituency that is affected by the provisions of the private bill;

- land, buildings or property owned by the member, their partner, family members or dependent children or in which the member, their partner, family members or dependent children have a right or interest, is affected by the provisions of the private bill;

- the provisions of the private bill will have effect in or on the constituency that the member represents;

- the member, their partner, family members or dependent children have a financial interest or derive a material benefit that directly relates to the provisions of the private bill or directly relates to the promoter of the private bill;

- the member, their partner, family members or dependent children are expecting to derive a financial interest or derive a material benefit that directly relates to the provisions of the private bill or directly relates to the promoter of the private bill; and

- there is any interest registered in the Register of Interests that in the opinion of the Business Committee will or would be likely to prejudice the ability of the member to participate in the Committee proceedings in an impartial manner.

111. As well as the above interests members may have other interests which may prevent them from being appointed to a private bill committee. It will therefore be the sole responsibility of the member to declare any relevant interest related to the work of a private bill committee to the Business Committee. On consideration of this information the Business Committee will recommend that the member be appointed or not.

112. If a member accepts the invitation to sit on a private bill committee they will be asked to declare, at the first meeting, that they will act impartially and base decisions solely on the evidence and information provided to the Committee.

113. As with any proceedings of the Assembly failure to declare an interest relating to the work of the private bill committee and to continue to participate in the committee may be subject to complaint and subsequent investigation by the Interim Assembly Commissioner for Standards. Members who accept appointment to such a committee should at all times be open with the Business Committee and the other members of the committee with respect to their interests.

Procedures for the private bill committee

114. The Committee on Procedures recommend that the quorum of the private bill committee will be three and full attendance of the membership will be required unless special circumstance prevents a Member from attending. A Member can not be deemed present if linked by video conferencing facility.

115. The Committee on Procedures recommend that a private bill committee will elect its chairperson and deputy chairperson at its first meeting and that voting will be by simple majority. Given the small number of members, the Committee on Procedures further recommend that in the event of a tied vote, the chairperson should have a casting vote.

116. The Committee on Procedures recommend that private bill committees may exercise the powers in section 44(1) of the Northern Ireland Act.

117. A private bill committee may appoint specialist or technical advisors.

Guidance notes to assist promoters and objectors

118. The Committee on Procedures recommend that, prior to the introduction of the Assembly’s first private bill, detailed guidance for promoters and objectors be published by the Bill Office. As such, legislation will be generated outside the Executive and the Assembly, the guidance will need to be comprehensive in order to ensure that the promoters have sufficient information to anticipate problems and prepare a bill competently. Guidance will also be required to ensure that objectors also have sufficient information to enable them to provide a written submission in the correct format.

Hybrid Bills

119. Erskine May defines Hybrid bills as “a public bill which affects a particular private interest in a manner different from the private interest of other persons or bodies of the same category or class.”

120. The Scottish and Irish Parliaments have never received a hybrid bill although they are not uncommon in Westminster. The anticipation is therefore hybrid bills will be a rare occurrence in the Northern Ireland Assembly and that the principles of scrutiny of such bill as per Westminster will be followed i.e. it will be referred to the appropriate statutory committee. For those provisions of the bill which are private in nature, the committee will follow the Standing Orders for private bills.

121. It is anticipated that a private bill will be identified as hybrid during preliminary scrutiny stage and as such the Speaker will be provided with the appropriate procedural advice at that step.

Diagram One - Stages for a private bill

Preliminary Scrutiny

- Assessment that the private bill meets the requirements as laid down in Standing Orders

Introduction (First) Stage

- Announcement by Speaker that a private bill has been received and will be published

- Agreement to establish a private bill committee (who will receive and assess objections to private bills, publish admissible objections and produce a report on principles of the private bill)

![]()

Second Stage

- Minimum of 60 working days after First Stage

- Debate on main features of bill

- Simple majority vote – the bill either will pass or fall

- If passed, the bill will be referred to a private bill committee

![]()

Committee Stage

- Commence immediately after Second Stage

- 30 days to consider and report to the Assembly

- Committee consideration of objections including voting on any amendments proposed

- Committee clause by clause consideration

![]()

Consideration Stage

- Minimum of five working days after the Committee tables its report

- Debate and vote on the clauses and schedules of the bill (as amended by the private bill committee)

- Any MLA may propose amendments

- Motion to refer substantial amendments back to the private bill committee may be tabled

![]()

Further Consideration Stage

- Minimum of five working days after Consideration Stage

- Opportunity to table amendments of an editorial or technical nature only

![]()

Final Stage

- Debate and vote on the motion “that the ...bill do now pass.”

[1] Written evidence from Scottish Parliament

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Wednesday 14 November 2007

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Lord Morrow (Chairperson)

Mr Francie Brolly

Lord Browne

Mr Willie Clarke

Mr Raymond McCartney

Mr David McClarty

Mr Sean Neeson

Mr Ken Robinson

In attendance:

Ms Stella McArdle (Clerk)

Mrs Elaine Farrell (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Linda Hare (Clerical Supervisor)

Apologies: Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Declan O’Loan

The meeting opened in public session at 2.05 p.m.

6. Private Legislation – Terms of Reference

The Committee discussed the detail surrounding the inquiry into Private Legislation which is scheduled to commence in January 2008.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the terms of reference, the list of potential witnesses and advisors, commissioned research, a best practice visit to Dublin, a press notice and a full day of evidence taking on 20 February 2008.

Lord Morrow

Chairperson, Committee on Procedures

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday 28 November 2007

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Lord Morrow (Chairperson)

Mr Mervyn Storey (Deputy Chairperson)

Lord Browne

Mr Willie Clarke

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Sean Neeson

Mr Declan O’Loan

In attendance:

Ms Stella McArdle (Clerk)

Mrs Elaine Farrell (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Linda Hare (Clerical Supervisor)

The meeting opened in closed session at 2.02 p.m.

7. Private Legislation

The Committee noted the public notice and the press release inviting written submissions to the Inquiry into Private Legislation.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the public notice and press release in relation to the Inquiry into Private Legislation

Lord Morrow

Chairperson, Committee on Procedures

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday 20 February 2008

Room 21, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Lord Morrow (Chairperson)

Mr Mervyn Storey (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Francie Brolly

Mr Willie Clarke

Mr David McClarty

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Declan O’Loan

In attendance:

Mr Martin Wilson (Principal Clerk)

Ms Stella McArdle (Clerk)

Ms Eleanor Murphy (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Eithne Knappitsch (Assistant Clerk)

Ms Linda Hare (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Gwyneth Deconink (Clerical Officer)

The meeting opened in public session at 10.35 am.

Private Legislation Inquiry – Oral Evidence Session

7. Briefing from the Scottish Parliament.

The Committee took oral evidence from David Cullum and Jane Sutherland from the Non-Executive Bills Unit of the Scottish Parliament. A question and answer session followed.

8. Briefing from the Assembly Research Services.

Ms Claire Cassidy of the Assembly Research Services briefed the Committee on the procedures governing private legislation in other legislatures.

9. Briefing from the House of Commons.

The Committee took oral evidence from Mr Alan Sandall, Acting Clerk of Bills at the House of Commons. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 12.14pm

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 12.23pm

10. Briefing from the Society of Parliamentary Agents.

The Committee took oral evidence from Mr Alastair Lewis, Mr Robert Owen and Mrs Alison Gorlov from the Society of Parliamentary Agents. A question and answer session followed.