Session 2007/2008

Third Report

The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

Report on the Inquiry into

the Prevention of Suicide

and Self Harm

Volume Two

WRITEEN SUBMISSIONS, OTHER EVIDENCE AND LIST OF WITNESSES

RELATING TO THE REPORT

Ordered by The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

to be printed 1 May 2008

Report: 27/07/08R Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Committee for Health, Social Services

and Public Safety

Membership and Powers

The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 46.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Consider relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquires and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on any matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mrs Iris Robinson MP (Chairperson)

Ms Michelle O’Neill (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Buchanan

Mrs Carmel Hanna

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr John McCallister

Dr Kieran Deeny

Ms Carál Ní Chuilín

Mr Alex Easton Ms Sue Ramsey

Mr Tommy Gallagher

Table of Contents

Volume One

Volume Two

Written Submissions

Other Evidence Considered by the Committee

List of Witnesses who Gave Oral Evidence to the Committee

Appendix 3

Written Submissions

Age Concern Northern Ireland

Introduction:

Age Concern Northern Ireland (ACNI) is a major voluntary organisation committed through campaigning and service provision to promoting the rights of all older people as active, involved and equal citizens. We act as a Northern Ireland-wide campaigning body and support a network of local Age Concern Groups operating throughout Northern Ireland.

We offer policy advice on a range of issues which impact on the lives of older people. These policies are based on:

- the expressed views of older people throughout Northern Ireland based on on-going contact and research;

- a knowledge of older people and an ageing society.

In 2003 Age Concern and the Mental Health Foundation launched the UK Inquiry into Mental Health and Well-Being in Later Life. This was because of a shared concern that mental health in later life is a neglected area with gaps between policies and services for mental health and those for older people. ACNI was represented on the Advisory Group which contributed to the

Inquiry. The Inquiry’s second report published by in August 2007– www.mhilli.org- reviews the services available to older people with mental health problems . We commend the Inquiry report to the Committee as a valuable source of information and guidance

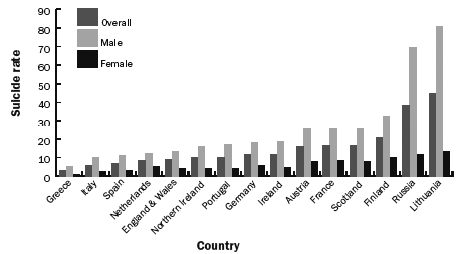

The Northern Ireland Suicide Prevention Strategy 2006-2011-Protect Life: A shared Vision has, and rightly so, focused on children and young people. However suicide and self-harm is also an issue in later life, with suicide rates across the UK remaining high for both older men and women, especially those aged 75 and over. Depression in older people is under-diagnosed and, even in diagnosed cases, under treated. In our view the Committee inquiry in examining the current strategic approach to the prevention of suicide and self harm should consider what can be done to improve levels of services and support for those aged 65 and over. Older people should be identified and included as a priority group within the scope of the strategy.

Suicide in Later Life.

Depression is the leading cause of suicide in older people. Between 71% and 95% of older people who die by suicide have a diagnosable mental health problem at the time of death (Beeston 2006 quoted in Improving Services for Older With Mental Health Problems) Risk factors for depression are therefore also risk factors for suicide. Better detection, prevention and treatment of depression will have the most effect on preventing suicides in older people. Other risk factors include sleep problems such as insomnia, and alcohol consumption, particularly in men.

Suicide in later life is marked by certain distinct characteristics

- Although older people make fewer suicide attempts than young people they are more likely to be successful in taking their own lives.

- Older people , especially men, use more lethal methods such as firearms and hanging. Older women often die by drug overdose.

- Older people are less likely to recover from a suicide attempt and are less likely to have someone intervene.

- Nearly half of older people who take their own lives visit their GP in the month before suicide.

Preventing Suicide.

There is a need to raise the profile of older people within mental health strategy and service provision so that suicide in later life will be recognised as the serious problem that it is.

Public education campaigns are needed to raise general awareness about suicide risk in later life. These should target family, friends and frontline workers in health and social care and others who have regular contact with older people.

Prevention strategy needs to give high priority to community based initiatives that reduce social isolation amongst older people. This could include telephone help-lines that target isolated and disabled older people.

Follow up services are needed for older people who have attempted suicide and those who deliberately self harm.

Reducing access to lethal means for men and prescription drugs (benzodiazepines and other sedatives) for women would have a positive impact.

David Savage

Policy Officer

Age Concern Northern Ireland

9th October 2007.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists

The Royal College of Psychiatrists is the statutory body responsible for the supervision of the training and accreditation of psychiatrists in Britain and Ireland and for providing guidelines and advice regarding the treatment, care and prevention of mental and behavioural disorders.

The College welcomes the Assembly Health Committee’s inquiry to examine the current strategy to prevent suicide and self harm, and is grateful for the opportunity to contribute to this.

Consultant psychiatrists lead multidisciplinary teams that are at the heart of the service in every locality in Northern Ireland, and as such work with people at risk of suicide on a daily basis.[1]

The College has 230 members in Northern Ireland, as well as younger doctors in training. These doctors provide the backbone of the local psychiatric service, offering inpatient, day patient and outpatient treatment, as well as specialist care and consultation across a large range of settings.

Every day throughout their professional lives psychiatrists assess suicidal risk; this is an integral part of the basic psychiatric assessment. Consultant psychiatrists will have spent up to 10 years in training in the full range of physical, psychological and social therapeutic techniques and are well placed to manage the most complex cases. Our contact with large numbers of patients gives an overview of many of the background factors that affect suicide and suicidal behaviour.

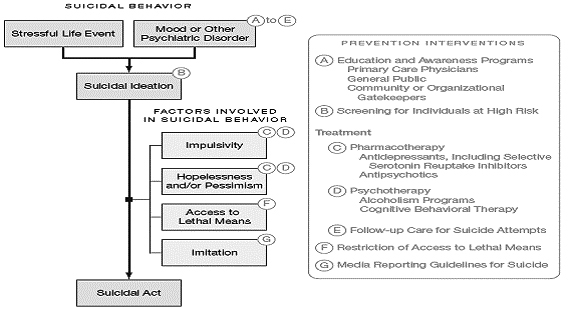

Suicide is a final act which always arises as a consequence of a great complexity of issues. It can be related firstly to severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or severe depression. Secondly, it may be associated with abuse of alcohol or drugs, personality difficulties or social problems. Often these are not easily remedied by direct medical intervention, although longer-term work may be of benefit to the person. Thirdly, suicide is also significantly linked to prevailing social and cultural issues within society, for example easy access to a means of suicide or a local suicide cluster.

About 50% of people have suicidal thoughts at some time, but each year just 0.01% (one in 10,000) die by suicide. It is clear that there is no single answer to dealing with our suicide problem; the only approach is for all of us, professionals, the voluntary sector, politicians, local communities, families and individuals as citizens to work together to provide a range of interventions.

The College has identified key areas that we believe are essential to tackling the problem of suicide. These are:

- Psychiatric services in general hospitals for those who have self-harmed, and the availability of specialist advice to hospitals for adolescents who are suicidal;

- The urgent need for more ‘talking therapies’; and

- A stronger societal response to alcohol misuse.

In addition, there is an overarching need to develop a mentally healthy society and to identify opportunities for real partnership between the statutory and voluntary sectors. The role of the media in overcoming stigma surrounding mental health and responsibly reporting on suicide cannot be underestimated.

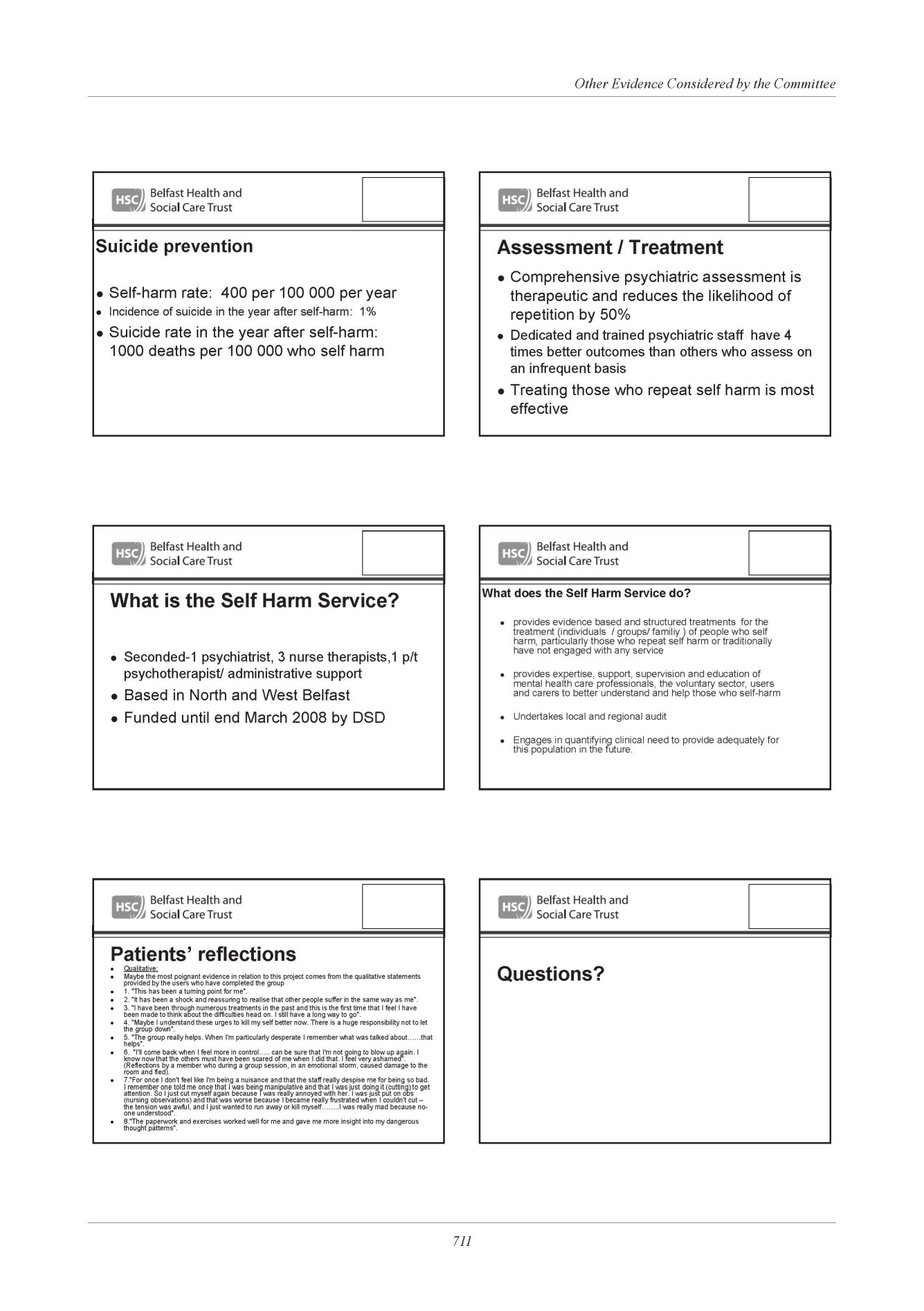

Psychiatric services in general hospitals for those who have self harmed

Recent research suggests that full assessment of self harm[2] cases is possibly the most important suicide prevention measure that can be taken.[3]

Of those who self harm, 1% are likely to complete suicide within the next year[4], an increase in risk of 100 times. This is clearly an easily identifiable group of people who are at risk and who can and should be offered thorough assessment and, if necessary, follow up.

Research indicates that when a person who has self harmed is assessed by a trained mental heath professional, the likelihood of repetition is reduced by 50% (NICE – The National Institute of Clinical Excellence 2004). Local audit has noted that a thorough professional assessment improves the outcome by a factor of 4. The NICE Guidelines (2004) demand that every patient is given a full psychosocial assessment after self–harm.[5]

Approximately 10% of those who present to A&E Departments with self harm are adolescents. The committee will be aware of the continuing difficulties in developing a comprehensive adolescent service which can provide expert advice to all Emergency Departments.

Ideally, each Emergency Department should be able to call on a rota of adolescent mental health professionals.

Unfortunately it seems unlikely that this will happen in the near future, particularly given continuing recruitment problems.

The Department of Social Development has recently funded a Self – Harm Service for North and West Belfast based at the Mater Hospital in Belfast to run until April 2008.

Under the leadership of Dr. O’ Kane, this team with specialist skills offers a comprehensive assessment and treatment to people who have self-harmed. This model is based upon best practice developed throughout the UK and North America and is the only service of its type in Ireland. Early results have been encouraging and a full audit of the service is being carried out.

On the basis of knowledge and skills particularly developed since 2004, the team runs a twice weekly, 16 week psychotherapy group for people who repeatedly self harm, often suffering from Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder. Middle aged females with this diagnosis are recognised as being at particular risk of suicide.

The Mater Emergency Department has reported a significant reduction in the attendance of such individuals with self–harming behaviour as a result. For the most complex patients there is an 18-month group. Early indicators of improved social and psychological functioning have been very positive.

This is currently only a temporary project. The College would strongly encourage the Committee to consider how this type of service can be more permanently made available.

The need for more ‘Talking Therapies’

Surveys often report that patients and the public in general would like more access to ‘Talking Therapies’ including psychotherapy and counselling.[6] There is a common perception that doctors are overly reliant upon medication. The reality is that Psychiatrists and GPs are as frustrated as the public at the lack of availability of psychotherapies. All psychiatrists have training and experience in psychotherapy, a number have specialised in specific therapies and others are local leaders in psychotherapy. However all too often the demands of providing a 24-hour service for all psychiatric illness within a defined geographical area means there is insufficient time for psychiatrists to offer more psychotherapeutic treatments.

Many of those who present to Emergency Departments having harmed themselves, particularly younger people, have problems related to interpersonal, social and personality difficulties rather than primary psychiatric illness. For these individuals it is much more fruitful to adopt a psychosocial approach. Such an approach requires both time and training.

The World Federation for Mental Health has said[7] : ‘A series of psychotherapies has been shown to reduce suicidal behaviour including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) , interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), dialectic behaviour therapy (DBT), psychodynamic / analytic psychotherapy and some forms of problem solving therapy (PST)’. The Federation went on to say that action was needed to improve treatment methods and facilities for suicidal individuals through psychotherapeutic interventions. It also called for more research into psychotherapy and counselling for those who have self-harmed.

The College reiterates its view that there is a real dearth of psychotherapeutic interventions for patients in N. Ireland, and calls for a real effort to address this.

The problem of Alcohol Misuse

Alcohol and drug abuse contribute significantly to suicide and self-harm behaviour. They often lead to depression, they can cause multiple social and financial problems, and they often lead to impulsive and risky behaviour. Every psychiatrist who sees patients in general hospitals is keenly aware that alcohol is a factor in over 50% of self– harm cases, and that people who are intoxicated and harm themselves in many cases would not have done so had they been sober.

In Northern Ireland there are well-developed addiction services, although more needs to be done.

The College takes the view that this is an area where public health and indeed public policy has a major role to play. Our cultural tradition is of relatively heavy binge drinking, particularly at weekends. This leads not just to an increase in self-harm but to high levels of aggression and violence.

It will be very difficult to change long-established patterns of behaviour in this area, but we must persist. The College believes that we must carefully review the issue of advertising on television. The sponsorship of sports by the alcohol industry is particularly alarming, given the high suicide rate in young men, the key target group of the advertising.

There is evidence that alcohol consumption is related to price and availability. While recognising that these are complex and politicised issues the College recommends, given our current suicide problem, that we look at the whole range of possible public health approaches to alcohol misuse.

Underpinning issues

The College welcomes the £3 million funding made available by the Minister to implement the recommendations of the Suicide Taskforce and warmly commends the commitment of a wide range of voluntary and community groups, as well certain highly dedicated individuals, who have contributed right across Northern Ireland to raising the profile of mental illness and its consequences.

The College was represented on the initial Suicide Taskforce and responded to the consultation. We have concerns however that there is sometimes a lack of communication between all the main stakeholders. We hope that the development of five large Trusts with coherent Mental Health leadership will enable real partnership working between the professionals and the voluntary sector.

To have a lasting reduction in the rate of suicide in Northern Ireland, we must start building a more mentally healthy society. This means working in schools to raise awareness of mental well-being, so that the next generation will have stronger emotional resilience and a better understanding of mental ill health. To be effective, this will require genuine cross-government working between the Departments responsible for health, schools, further education, training and employment. Mental health must be put on the school curriculum, with parents and teachers also given information on supporting a young person with a mental health problem. The Royal College of Psychiatrists has a range of free materials that can be downloaded from our internet site.[8]

There is an abundance of international evidence that shows the role the media has in combating the stigma of mental health problems, but also the risk of triggering suicide through irresponsible reporting or portrayal. Stigma prevents people from getting help early, or in some cases at all. We are aware that the Minister’s team is working with the media to promote safe reporting, and hope this will continue. We commend the Health Promotion Agency’s awareness campaign, and hope to see further marketing approaches to combating stigma.

Conclusion

The College is keen to assure the Committee that its members remain deeply committed to doing everything within their power, at the clinical and the policy level, to provide the best care possible for the mentally ill and particularly those at risk of suicide.

Appendix One (Glossary)

Self – Harm

A deliberate non-fatal act, including overdosing, cutting and attempted hanging, done in the knowledge that it is potentially harmful. It can be conceptualised as a non-verbal externalised communication.

Psychotherapy

A talking technique through which the therapist helps patients find relief from emotional distress. Its success depends upon the therapist’s ability to understand the patient and the patient’s use of the therapist.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (Cbt).

This treatment is based upon the premise that the way the patient thinks (‘negative automatic thoughts’) can lead to depression and other problems. The therapist helps the patient identify and change the negative thoughts.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

A therapy based on the premise that problems in interpersonal relationships including bereavement, disputes and life changes can lead to depression. The therapist helps the patient to improve their interpersonal communication and to develop new attachments.

Dynamic Psychotherapy

A treatment in which the therapist helps the patient to understand and deal with current problems in the context of what has happened in the past.

Multidisciplinary Teams

In the community psychiatric care is delivered by a team of professionals working closely together, including psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses, mental health social workers, occupational therapists and sometimes psychologists.

APPENDIX 2

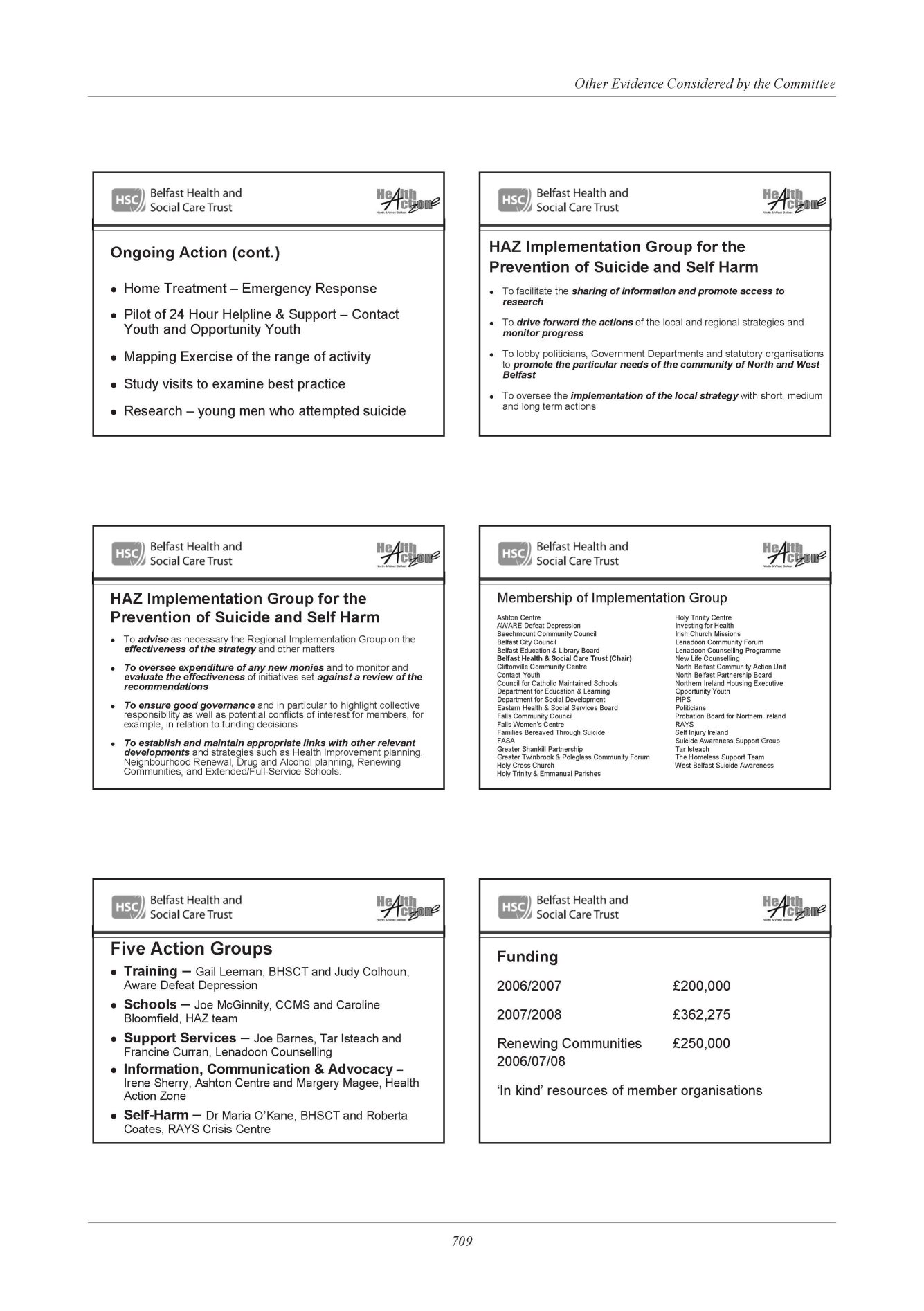

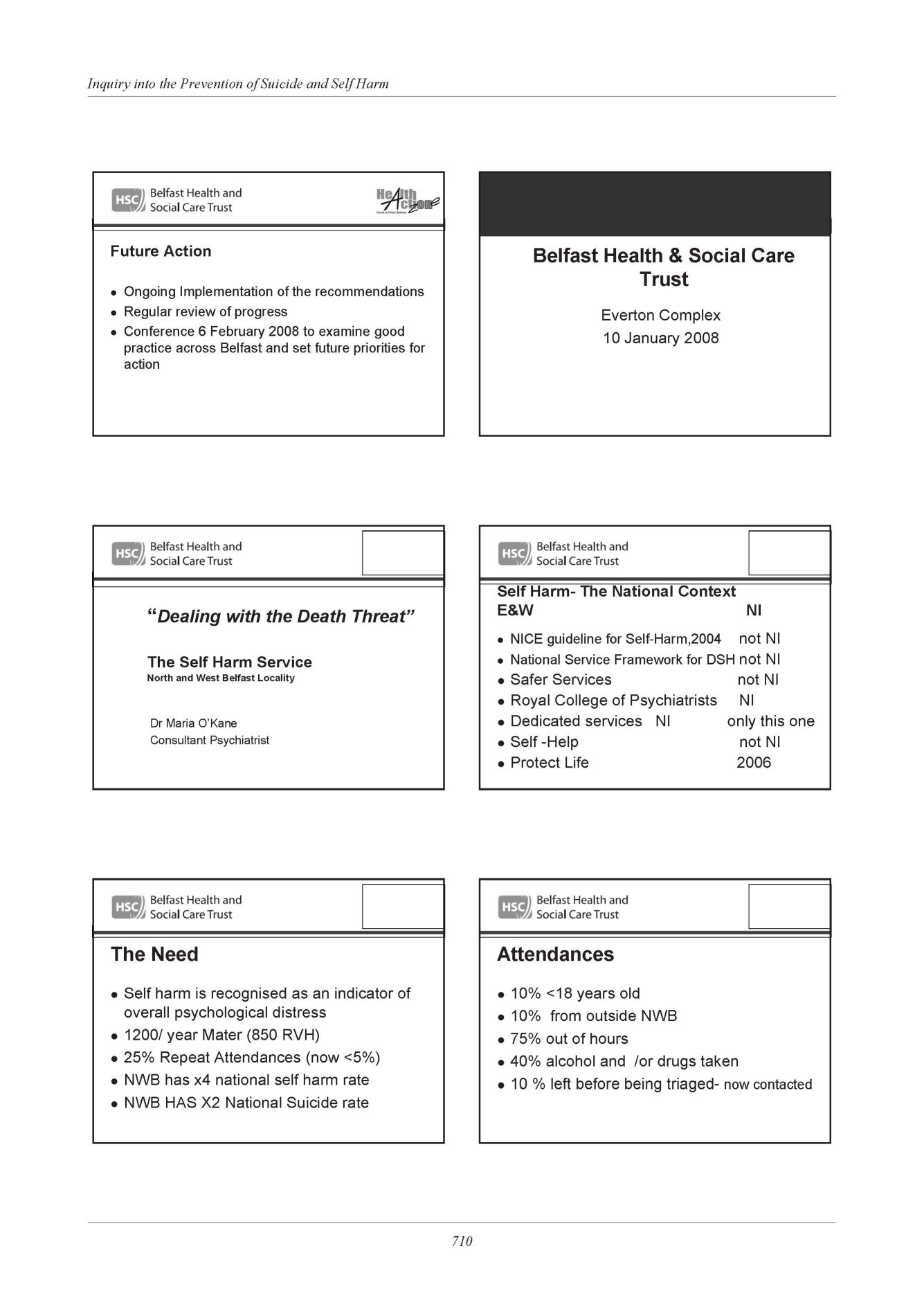

The Self Harm Service North and West Belfast

The Self Harm Service for North and West Belfast is based at the Mater Hospital. It has been funded by the Department of Social Development through the Renewing Protestant Working Class Communities Initiative until April 2008. It currently consists of a consultant psychiatrist in psychotherapy /adult psychiatry, 3 mental health nurse therapists, trained in the range of psychotherapies, a part-time psychoanalytic psychotherapist (10 hrs per week) and administrative support.

Across the Mater and RVH A&E departments there are currently up to 50 presentations for mental health reasons, 90% of whom present with self harm per week. There is one full time psychiatric liaison nurse based at the RVH (mon-fri 8.30-4.30pm) and 1.4 psychiatric liaison nurses based at the Mater (8.30-4.30pm daily). This provision is regarded universally as being wholly inadequate, particularly at times when annual leave has to be covered.

The Self Harm Service interfaces with the Psychiatric liaison services at the Mater and RVH sites. It provides rapid follow up to people discharged from A&E assessed as at increased risk of self harm and suicide, through short-term one to one interventions.

Where longer term work is required, particularly for those who repeatedly self harm and present with other challenging behaviours, an initial twice weekly 16 week self harm programme is offered, and where required, a longer term group for those with emotionally unstable personality disorder, where repeated self harm is a constant feature of the disorder.

In addition, through government agencies such as the Health Action Zone, the Team works in partnership with users, carers, community and voluntary sector representatives.

The Team leads the “Better Services for People who Self Harm “audit in North and West Belfast run by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in collaboration with the Royal College of Nursing, College of Emergency Medicine, LAMP and the Ambulance Service Northern Ireland.

The Self Harm Team has been trained by experts from England and North America. In addition, it now provides expert trainings (such as STORM) to other professional groups. Within the framework of the Protect Life Strategy in conjunction with the Health Promotion Agency, we are developing a regional Self Harm and Suicide Prevention training strategy for North and West Belfast to be considered for Northern Ireland.

In addition we have organised a number of User led initiatives and conferences.

Aims

1) To provide a rapid and comprehensive follow-up to those people who have attended A&E following an episode of self-harm. In collaboration with existing Psychiatric Liaison Nursing Services (PLN) at the Mater and the RVH sites, the Self Harm Team targets a group of people who traditionally would not receive a rapid follow-up service, who are at an increased risk of completed suicide (Hawton and Fagg 1992, Nordentoft et al 1993 and Powell et al 2000).

2) To provide ongoing treatment and support, particularly group interventions, to those people who have a history of repeated self harm.

3) To participate in local and regional Audit and research of Self Harm Services

4) To provide advice and teaching and training to others involved in the provision of services to people who self harm

5) To liaise and where appropriate to work with all relevant statutory and non-statutory organisations, locally, regionally and nationally.

6) To develop and maintain effective working relationships with all stakeholders involved in the delivery of mental health services to provide, where possible, a seamless service within the community.

7) To promote partnerships among practitioners, service users and carers.

The Profile of the Service Users

Of those who attend the service because of repeated self harm, a profile has begun to emerge. The age range is 18-66 years.

23% have been in care as children

72% have been in contact with the criminal justice system, usually for minor offences

60% have a history of drug and alcohol misuse

60% have a history of childhood sexual abuse

35% have a history of teenage pregnancy

50% have young children

65% have history of social services involvement

100% are on state benefits

100% have a history of failed employment

100% have a history of repeated broken relationships

100% have received psychiatric inpatient care in the past

82% have a diagnosis of Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder

30% have a history of eating disorders

30% have been on the peripheries of paramilitary activity

Following Contact with Services, Outcomes to date:

90% have consistently reduced their self harming behaviours

The usage of the overall percentage of A&E services has dropped from 25% of all attendances to <5%

25% have completed NVQs, HNDs or begun Third Level Education

10% have begun part-time paid employment

Hospital Admission has dropped with fewer than 10% now using psychiatric hospital admission, and now on a respite or severe crisis basis only

[1] Appendix 1 explains the roles within the multidisciplinary team.

[2] Self harm is explained in Appendix 1

[3] Professor David Owens of Leeds University and Dr Navneet Kapur of the Manchester Centre for Suicide Prevention (British Journal of Psychiatry 2005)

[4] Keith Hawton (2000)

[5] Clinical Guideline 16, Self Harm, NICE 2004

[6] For more information on Talking Therapies, see Appendix 1

[7] World Federation for Mental Health (2006)

[8] http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mentalhealthinformation/mentalhealthandgrowingup.aspx

The Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland

1. The Committee is invited to note that the role of the Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland (HSENI) is prescribed by the Health and Safety at Work (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 as amended by the Health and Safety at Work ( Amendment) ( Northern Ireland ) Order 1998.

2. This limits HSENI’s role to one of regulating health and safety within the context of the workplace. HSENI therefore works to try to encourage preventative workplace strategies based around promoting good mental health and well being that in the long run may mitigate the stressors that arise from work that might contribute to someone self harming or committing suicide.

3. HSENI has concentrated on preventive strategies aimed at particular work sectors such as the health sector where work related stress has been identified as a causal factor in sickness absence. These interventions are aimed at delivering a positive effect on the health and mental well-being of people within organisations through the adoption of good stress management practices.

4. HSENI is working with the Northern Ireland Civil Service Occupational Health Service to study the causes of sickness absence and in terms of mental health HSENI is working with the Department of Finance and Personnel Central Personnel Group helping it adopt the UK stress management toolkit for the workplace, known as the Stress Management Standards.

5. In addition HSENI has worked with other public sector employers such as the District Councils and further education colleges encouraging them to identify and begin to manage stress related issues and to encourage the use of the toolkit. This work has been piloted under the banner of “Workpositive” and will be further extended during 2007/08 with new work sectors being challenged.

6. In the current year HSENI will challenge the education sector to tackle the issue of stress related ill health amongst teachers. HSENI has already participated in the NASUWT conference held in Belfast, with an advisory stand for the teacher delegates.

7. At a strategic level, HSENI will be engaging with other stakeholders through the further implementation of the long term Northern Ireland Working for Health Strategy. This second phase of this strategy which embraces all work related health issues including mental health will commence in October 2007. How great an impact the strategy will make will be dependent on the outcome of the Comprehensive Spending Review.

8. In addition HSENI is proposing an initiative called “Safestart-NI” which is aimed at school leavers in the 15 to 18 year old age group with the intent of providing knowledge and skills for young people entering work for the first time. This programme will build capacity and self esteem amongst the very young people who unfortunately account for increasing numbers of suicides. This is also subject to successfully obtaining funding under CSR07.

9. In conclusion HSENI is not in the front line when it comes to tackling the issues of suicide and self harm. However the work that it can do within a workplace setting may well lessen or reduce the likelihood of employees going on to self harm or suicide if they enjoy a working environment that fosters well being.

Kevin Toner

Deputy Chief Executive

HSENI

11th October 2007

Professor Kevin Malone, MD, FRCPI, FRCPsych.

Thank you for your invitation to submit memoranda in relation to the Committee Inquiry into the prevention of suicide and self-harm. I come to the problem of suicide in Ireland following 20 years of research in suicidal behaviour including suicide in the US in the 1990s, and having been appointed as Professor of Psychiatry in the School of Medicine and Medical Science in UCD since 2002.

Research

Since my return to Ireland in 1998 I have established a North-South Suicide Research Programme called the Ireland North-South Urban Rural Epidemiologic Collaborative Study of Suicidal Behaviour and Major Psychiatric Disorders (the INSURE Project). Over the past six years this project has interviewed over 1000 sufferers from mental illness with varying degrees of suicidialty affiliated with their condition. These clinical interviews took place both in outpatient clinics (Study 1), as well as in emergency departments (Study 2) in six locations on the island of Ireland, including Dublin, the Midlands, Ballinasloe, Letterkenny, Omagh and Belfast. This project was collaboratively designed with Queen’s University Belfast (Prof. Roy McClelland, Dr Chris Kelly and Dr Tom Foster). Study 3 of the INSURE study has taken place in the south of Ireland focussing exclusively on a psychological autopsy study of Lives Lost to Suicide in Ireland in the past three years. We have currently interviewed the families and friends of fifty suicide deaths since our project started in earnest in January 2007, and we anticipate that we will have interviewed seventy families by the end of the year.

UCD Research

The Suicide Research Programme we have developed here at University College Dublin in collaboration with other institutions nationally and internationally includes three major strands:

i. Clinical and Applied Neuroscience, including molecular genetics and functional brain imaging. This strand focuses on neurobiological studies of suicidal depression, understanding brain pathways and genetic regulation of impulsivity and restraint and with impact on mood disorders and the emergence of suicidal behaviour.

ii. Clinical epidemiology, randomised control trials and health economics: this strand focuses on many of the aspects of the INSURE Project. As well on the clinical epidemiology side we have completed a study of all drownings in Ireland in the past five years, as well as all railway suicide deaths in Ireland in the past twenty years. Preliminary findings from these projects were presented at the recent IASP Conference in Killarney and further information will be provided on request.

Continuing with epidemiology we have a link with the DETECT Project, First Episode Psychosis, which is being led by Prof. Eadbhard O’Callaghan. This study is of a group at obvious increased risk for suicide in the first episode of their psychotic illness.

Health Economics is an under-researched area in relation to the problem of suicide and we have linked up with our economic colleagues in the Geary Institute at University College Dublin (Prof. Cecily Kelleher and Dr Liam Delaney) to study economic factors associated with suicide in modern Ireland.

iii. Strand three is Community and Humanity. This strand focuses on the impact of suicide on communities and one of the foci of the Suicide in Ireland Survey. The unique additional component to this Suicide in Ireland Survey is the carrying out of the first ever Visual Arts Autopsy in parallel with the psychological autopsy enquiry. This has the added bonus of combining clinical science with arts and humanities research, and all the families we have interviewed have warmly welcomed it. The other unique possibility associated with the Suicide in Ireland Survey is the platform to study the occurrence of clusters and even in our first forty-six cases we have identified an additional forty-seven cases that more than likely were associated with cluster effects. Again, these preliminary data were published and presented at the IASP meeting in Killarney and can be shared in greater detail at your request.

PhD Programme in Suicide Studies

UCD is the first university in Ireland to put together a PhD Programme in Suicide Studies. We appointed our first PhD student in September 06 and we will be taking on a further two PhD students in January 2008. These three students are looking at very different components of suicide in Ireland and they will make a unique contribution to fourth level education in this regard. I believe this is one of the ways forward with regard to attracting new and talented researchers into the field.

All Island Approach

It has been my opinion since my return to Ireland in 1998 that an all island approach was required to the research of the problem of suicide and deliberate self-harm in Ireland, and particularly the problem of suicide. It was for this purpose that I established the INSURE Project. This project has a wealth of data, which unfortunately we have not had the funds to properly analyse. We presented the first poster on the Year 1 data from this project at the IASP Conference in Killarney and this can be provided to your Committee, if it is desired. The advantage of the INSURE Project is that our research areas straddle the border counties and also urban and rural sites in both Northern Ireland and in the Republic, and also include areas of significant deprivation such as the border, midlands and west. The major drawback to not being in a stronger position with regard to new knowledge from these projects has been the lack of resources and also lack of sustained resources over time so that properly planned studies can be implemented.

Northern Ireland Research

Dr Tom Foster in Northern Ireland conducted a psychological autopsy study in 1994 of all suicide deaths in Northern Ireland. Whilst that is only twelve years ago things have changed dramatically on the island since that time and I believe there is significant merit in considering an all island psychological autopsy study, particularly of young suicide deaths under the age of twenty-five. Dr Tom Foster is ideally placed, and trained from an expertise point of view, to lead this study in Northern Ireland and I would be happy to continue leading this study in the South. However, I firmly believe if a research programme is to be successful it requires guaranteed resources for a specific period of time, rather than wondering from one year to the next whether or not funding will be sustained. These studies are labour-intensive, they are hugely rich in terms of the data they can provide, and I have adopted a case control designed to my protocol, as recommended by the International Association for Suicide Research in New York in 2006, and this strengthens the methodology considerably.

DSH

I am sure you will have had input from the National Suicide Research Foundation in Cork and their experiences with the National Parasuicide Register, which obviously is providing new data on deliberate self-harm more so than of suicide. Nevertheless, it is a valuable resource that probably should be extended on an all island basis. There are some problems with that Register that may require ironing out before it would be considered compatible for the entire island.

Mental Illness

All the international studies clearly demonstrate that a significant component of suicide deaths are associated with varying degrees of mental illness. To my knowledge in the Republic, there has been no proper audit to date in terms of exactly what statutory and voluntary services are available for (a) people (especially young people) with emerging mental illness and (b) particularly those in suicidal crisis. Whilst documents like “Vision for Change” and “Reach Out” are government policy documents here in the Republic, there is no sound, solid foundation to say “here is our starting point, this is what we have, this is what we do not have, this is what is available, this is what is not available, and here is what is available in part of the country A versus part of the country B”. Nor is there any real meaningful client feedback services or data, which is a real shortcoming in health strategy.

International Lessons

Much can be learned from the response to suicide statistics in other countries. For example, Finland has experienced a significant reduction in suicide deaths over the past fifteen years. Their approach was extremely methodical and focused particularly on early recognition of treatment of depression and alcohol problems, as the major planks of their strategy.

Schools

Much has been written and spoken about “going into schools” despite any robust data to indicate that this may be effective. I hosted a two-day Dublin International Workshop on Youth Suicide on 25 and 26 August 07 in the Royal College of Physicians where over twenty leading youth suicide experts presented their findings from around the world. We are currently writing up the proceedings of this Workshop and hope to publish it in a major international journal. One of the sessions, however, was on school-based interventions and Prof. David Schafer from Columbia University New York had very little confidence in the effectiveness of school-based intervention, as opposed to case finding studies in schools, which is a very different approach.

NOSP

I am an advisory board member to the National Office of Suicide Prevention and I am aware that your office in Northern Ireland has been in close consultation with the national office here so I will not cover that territory in this submission.

Large Scale Intervention Projects

An all island approach will also be necessary for large-scale intervention projects designed to demonstrate effectiveness in reducing suicide rates. Such studies have been effective in other countries such as Hungary. Further information can be provided on this if necessary.

Advocacy

In 2002 I co-founded the charity, 3Ts (Turn the Tide of Suicide) with Irish businessman, Mr. Noel Smyth. Over the past five years we have aimed to increase awareness of the problem of suicide and also to raise funding to support existing voluntary agencies on the ground around the country who are involved in suicide intervention, prevention and postvention. As you are probably aware, there are at least three hundred voluntary organisations dedicated to various suicide awareness and prevention projects in the Republic. The 3Ts has aimed to pull many of these charities and voluntary organisations together under a united umbrella, The Action on Suicide Alliance, and so I have forwarded your correspondence to the Chairman of the 3Ts, Mr. Noel Smyth to provide feedback to you on the activities of this charity.

Summary

I do believe, in summary, and based on what I have outlined above that we have a unique opportunity to build an all island research education, intervention and prevention programme right across the communities that will be inclusive as opposed to exclusive, and that with sufficient and sustained resources and planning we could emulate the success of our neighbours in Finland and Denmark, for example, who have seen their suicide rates decline between 20% to 40% in the last two decades through targeted, dedicated, and well-resourced strategies, programmes and projects led from within communities and facilitated by devoted national leadership.

Young at Art

We have received information about the inquiry via the Youth Council for Northern Ireland and would submit the following for consideration.

It is our organisation’s mission to make the lives of children and young people as creative as possible through engagement with the arts. As such we are committed to supporting and protecting children and young people and support the NI Assembly and its committees in pursuing any cross-departmental strategy that reduces suicide and self-harm.

In our experience over ten years of working with children and young people across Northern Ireland, we feel that the success of any future strategy is dependent on cooperation between all departments. We also believe that coherent structures for communicating that strategy to and between grassroots organisations are vital.

We would strongly advocate investment in existing resources and structures to tackle the causes of suicide and selfharm – low self esteem, lack of opportunity, limited education and employment opportunities, limited access to mental health support, lack of communication and interpersonal skills, sectarianism and bullying. We would advocate planned and negotiated longterm investment with existing structures over and above the creation of shortterm posts to address this issue.

As an arts organisation, we believe that creative activities have a key role to play in supporting personal skills development and promoting the issues around suicide and self-harm. Key strengths of the arts in tackling these topics are:

- The ability to explore sensitive issues at a safe distance through drama, performance, literature, film and the visual arts

- The ability to engage with young people in ways that interest them – through music, design and live events

- The opportunities to articulate one’s feelings in ways other than speaking – projecting them visually and non-verbally

- The opportunity to build social support networks through arts activities and groups, filling a gap that often opens in young people’s lives when they are experiencing any mental trauma.

The arts have been proven in supporting the rehabilitation of young people following trauma both in Northern Ireland and across the world. Live theatre and film have been used in an educational context to examine and raise awareness of a range of personal health and emotional wellbeing issues among young people with very positive results. As such we would request that consideration be given to creative and cultural activities as a part of the framework for tackling the ongoing difficulties experienced by young people in Northern Ireland.

Specific examples are the work undertaken by our organisation with Amnesty International to both raise awareness of children’s rights and support alcohol free activities for 16 – 18 year olds and our work to promote physical health among parents of very young children; the work of Replay Productions in collaboration with the Health Promotion Agency, DHSSPS and RoSPA to develop touring theatre programmes on personal safety, sexual health, suicide and anger management and drug awareness; the work of Belfast Community Circus with young offenders since the 1980s; the work of Wheelworks in a range of disadvantaged communities to address anti-social behaviour, sectarianism, racism and to support the needs of Section 75 groups.

We welcome the opportunity to contribute to any further consultations.

Ali FitzGibbon

Director

Mr Chris Smallwoods, Regional Manager, The NEXUS Institute

Suicide is indeed an emotive and sensitive subject and from the experiences of The NEXUS Institute in relation to our specific client base the reasons for attempting or successfully carrying out the act would likely be very much related to the suffering which may have been caused by the individual having been subjected to prolonged childhood sexual abuse or even rape/violent sexual attack.

In relation to the implementation of effective interventions the NEXUS Institute has carried out research into the value of counselling services in dealing with the impacts of childhood sexual abuse and rape. Sixty three clients participated in the study and completed a questionnaire during 20 / 30 minute telephone interviews conducted with Nexus counsellors.

The biographical profile of participants was 92% (58) of the sample were female and 8% (5) were male. What is worthy of note in terms of this related subject was that 59% (17) of cases, related to mental health issues.

The personal aims which clients had for undergoing counselling included feeling better, greater understanding, learning to cope, reclaim their lives, and increase their self confidence and esteem.

The two most common goals were “to feel better” (21%) and to achieve “greater understanding” of the reasons why they were victimised and how this had affected their lives. (19%). Thirteen people stated that they wanted to feel better, particularly from depression or suicidal ideation.

It did become apparent that the majority of respondents were struggling to cope with the emotional, cognitive and social sequelae of their abusive experiences. Eleven percent (7) stated that they were depressed to varying degrees, i.e. some stated that they were seriously depressed and two people reported having attempted suicide and another experienced panic attacks. The inability to cope with their emotions such as feelings of guilt or shame, along with intrusive memories was a common problem.

Overall, whilst many perceived themselves to have experienced high levels of difficulties prior to counselling, they also felt that having undergone counselling, they observed significant improvements immediately after and at 6 months after counselling. Arguably, the most worrying statistic is that prior to counselling, 66% (29) of all of the individuals who participated in the research felt suicidal before receiving any help at Nexus. Fifty percent (29) strongly agreed with this statement and 11% (5) agreed, with another 11% (5) undecided. Immediately after counselling, only 2%, which represents one person still considered themselves to be at high risk of committing suicide. However, another 16% (7) agreed with this statement and therefore were still at risk of ending their own lives. However, six months after completing their counselling with Nexus, 14% of clients experienced a desire (14%, 5) to commit suicide. It is encouraging to note that none of the clients expressed a very strong desire to commit suicide, which would suggest that the intervention of counselling was successful in helping to reduce or in some cases eliminate suicidal ideation.

They also reported a decrease in the reliance of potentially risky coping tools such as the consumption of alcohol, self harming and even suicide. There was also an increase in the use of more positive strategies, such as reframing negative thoughts and emotions through talking about it to a supportive person, which were taught as part of their counselling courses. Many clients also attributed their difficulties to their poor health or specific health problems and a few commented that since undergoing counselling their mental and emotional health had improved. One individual commented that the progress they had made was “remarkable” and it was imperative to their mental health.

However for counselling to be effective it cannot be taken as a ‘stand alone’ intervention where there are serious mental health concerns but should be supported by meaningful mental health professional back up, particularly so when the client has entered into the counselling process and it is highly probable that many traumatic and frightening memories will re-emerge and thus impacting on the overall state of that clients vulnerability and mental health. In terms of my project there have been instances when clients have had to be denied access to counselling because those resources could not be put in place by the mental health teams of the region, which I was advised was due to a lack of resources (CPN’s). However a model of good practice does exist in one outreach site where there is a solid and effective working relationship between the counsellor, client and mental health resource which works very effectively.

From the experiences of both the agency and our client base what does stand out is the recognised need for an increase in awareness for men about the many obvious benefits of ‘Therapies for Men’ in terms of the counselling intervention. There is clear evidence to indicate that men suffer from emotional distress and that they will seek counselling only half as often as women which is particularly the case within the areas of male sexual abuse and rape. Our own statistics highlight a gender delivery of 82% female and 18% male, these figures would not be representative of reported abuse and rape incidents but it would be fair to say that the comparison of those seeking help against the likely levels of reported and unreported abuse would indicate that there is a definite reticence amongst males to come forward and seek counselling help.

In relation to training and development within our specific work area all our counselling staff are qualified and if not already in receipt would be working towards accreditation of an approved body such as BACP. It is also our intention that all counsellors and secretarial staff (first point of contact for clients) would have attended the well advertised and available ASIST courses.

Whilst The NEXUS Institute is both established and recognised as the leading agency in terms of providing support and being an accessible part of a support network in local communities for those who have suffered sexual abuse or rape there continues to be instability and uncertainty around the issues of both appropriate and secure funding and it is felt that this needs to be resolved as a priority.

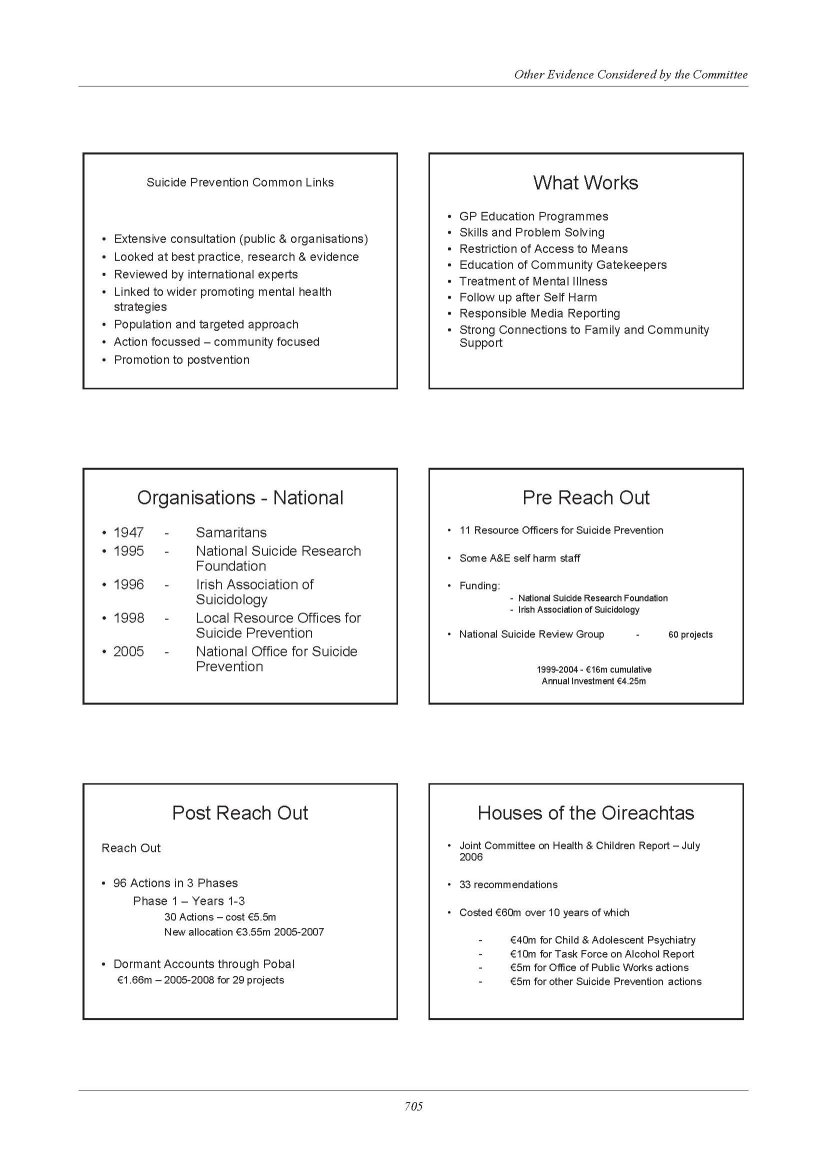

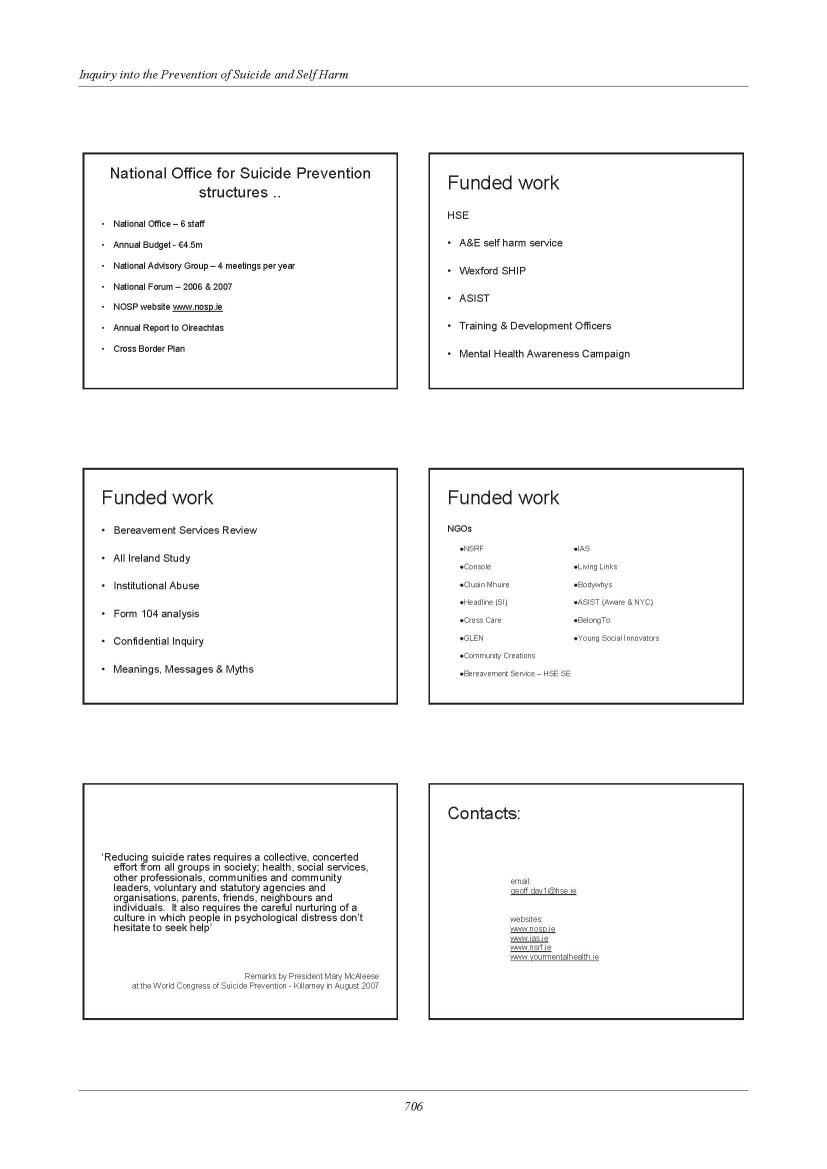

National Office for Suicide Prevention

Evidence to the Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety – Northern Ireland Assembly – Committee Inquiry into the Prevention of Suicide and Self Harm

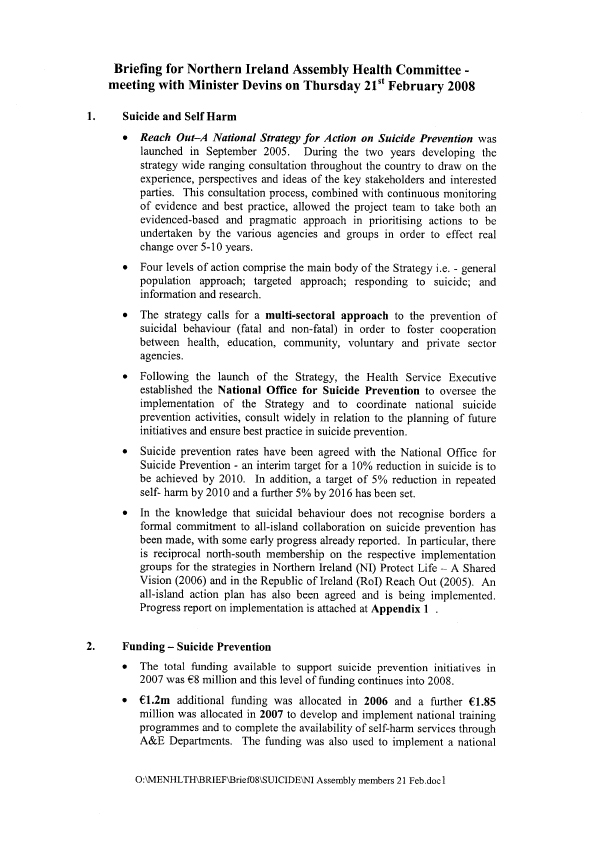

1. Background:

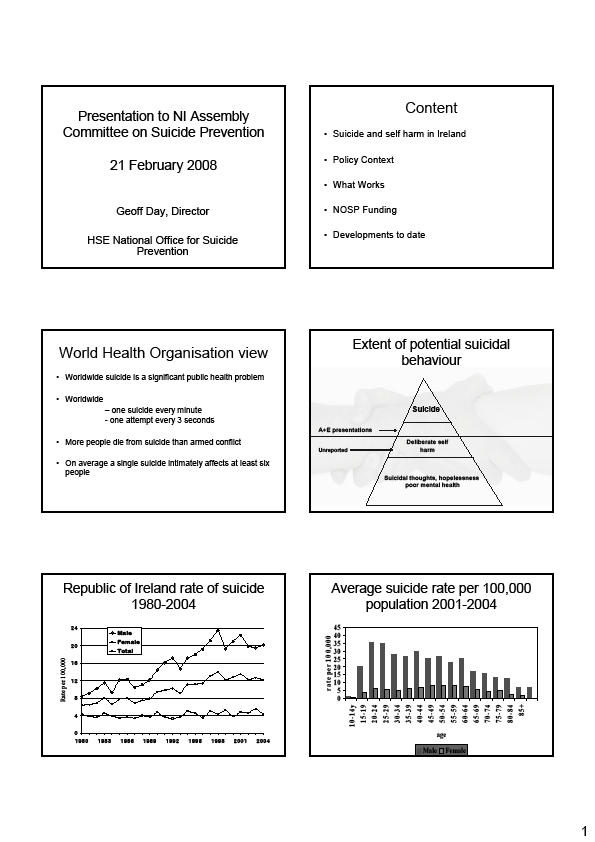

Reach Out the National Strategy for Action on Suicide Prevention in the Republic of Ireland was launched by the Minister for Health and Children, Mary Harney TD in September 2005. The report followed extensive public and organisational consultation and was approved by both the Department of Health and Children and the Health Service Executive jointly.

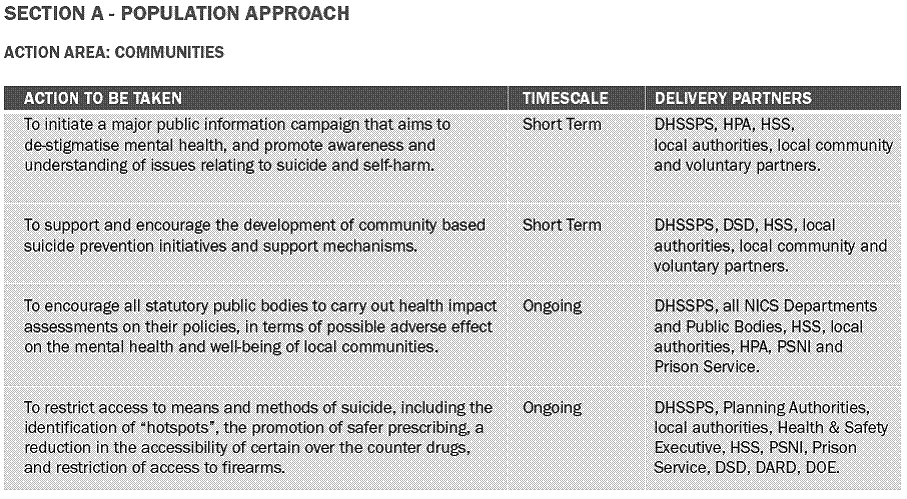

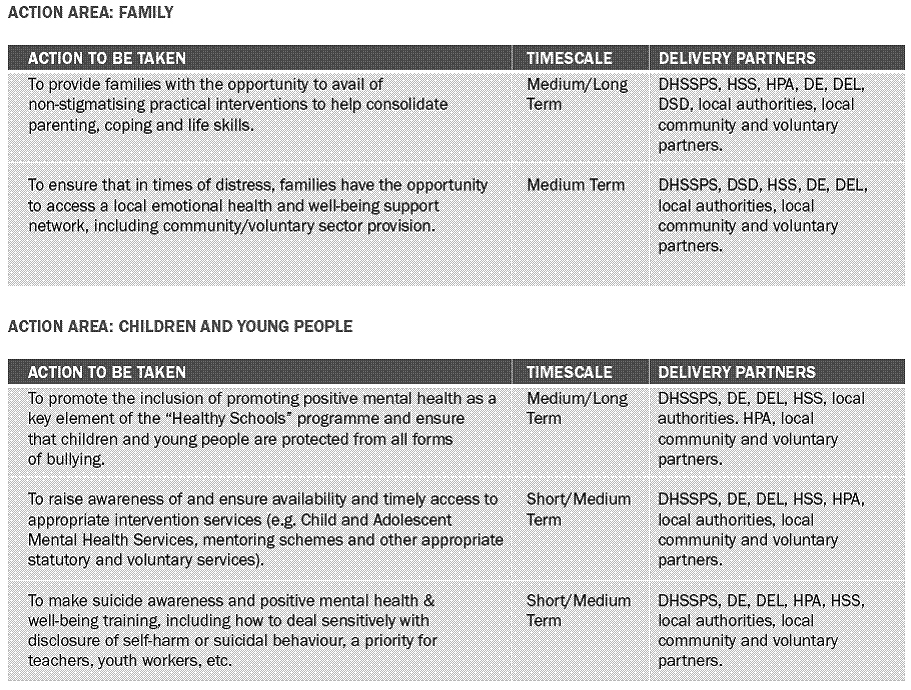

Reach Out has 26 Action areas and 96 actions to be taken over the 10 year span of the strategy. Dividing the actions into General population and specific targeted areas follows the World Health Organisation suggested approach and this is noted in other countries strategy documents.

In order to provide a focus for implementation the HSE established the National Office for Suicide Prevention (NOSP) within the Population Health Directorate in September 2005. This Office has national director and currently 5 staff members. The Office has established a national advisory group of people with expertise in the field of self harm and suicide and an annual forum of all interested parties. The office has its own web site www.nosp.ie and links to the HSE web site and those of the key voluntary organisations.

The HSE is required by legislation, the Health (Miscellaneous) Provisions Act 2001, to submit to the Houses of the Oireachtas, an annual report on the actions taken in the previous year to prevent suicide. A copy of the report is enclosed and will also be available soon on our web site.

2. General Response:

Protect Life – The NI Suicide Prevention Strategy has taken a similar approach to our own strategy and therefore many of the actions are compatible in terms of implementation. Funding to deliver the elements of the strategy is key. In our experience such investment needs to be significant, targeted and sustained over time.

The National Office has worked with colleagues in the DHSSPSNI and the HPA to agree an all island action plan on suicide prevention. This plan is the basis for joint actions across the island. A copy is attached. Most significant has been the work around awareness campaigns in the media, the most recent being the launch of a new TV/radio advertisement in both jurisdictions.

There are substantial advantages to joint working not least the cost effectiveness of combining resources and not re inventing actions already taken. We can learn from each others experience of implementation, indeed we can and are learning from our UK and world wide colleagues. The successful joint funding of the recent World Congress on suicide prevention held in Killarney has enabled us to achieve jointly a high profile for suicide prevention in Ireland.

Additionally we have established a 5 nation’s strategy group comprising Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Wales, Scotland and England

a) Assess the scope and appropriateness of the Department’s Strategy – Protect Life

The Strategy is set for a period of 5 years which in our view is sufficient for implementation and monitoring of progress to establish if a reduction in suicide levels can be achieved. Ongoing evaluation of individual programmes is necessary and all NOSP projects are asked to establish evaluations the intensity of these being related to the sum of funding involved and the capacity of the organisation concerned. Reachout has been in place for just over 2 years and we are now about to commission an independent evaluation of progress so far with the strategy and the operation of NOSP. We would recommend that Protect Life adopts a similar approach.

Protect Life sets clear targets for reducing suicide levels. While we originally did not set targets due to concerns over the reliability of data we have now done so even though the recording of suicide data is still a concern. We have taken the view that a target does allow us all to focus our efforts and be accountable for actions taken. As well as setting a target recently for reduction in suicide we have also set a target for the reduction in the rate of repitition of self harm

b) Examine the level of stakeholder involvement

A central part of the work of NOSP has been the engagement with other stakeholders namely, those bereaved through suicide, voluntary organisations at local and national level working in this area, professional bodies, and statutory organisations. We use a national forum every year to meet with all those on our extensive mailing list who have an interest in this area. The Forum is designed to provide information about the work of the NOSP, discuss recent evidence based initiatives and consult with stakeholders on future direction.

We have been impressed by the work of the Families Forum in NI and whilst we have similar families groups in the South they do not yet meet together as a national grouping. There is an opportunity in the future to establish an all island network of bereaved families

c) Examine the level of services and support

Whilst it is difficult to comment on individual services in NI we would state that it is important to develop services and supports across the spectrum of the strategy, from health promotion to postvention. We have tried to use our limited additional resources in this way although it does often mean that service development can be constrained and slow to progress.

We have been encouraged by the willingness in NI to take some of the initiatives already underway in the South e.g. self harm registry data collection, media watch, to develop all island coverage. We have worked together on mental health awareness campaigns and the world congress on suicide prevention. We will be further examining initiatives in NI which we can adopt in the South

d) Consider what further action is required

Cross border co operation to date has been effective with good working relationships with both the DHSSPSNI and the HPA. It would be helpful if there was similar organisation to the NOSP in NI as this would allow for one contact point for this office. Also in our experience the establishment of the office has provided a national focus for all our initiatives as well as a central coordination role. For government it provides a single channel through which Dept of Health and Children funding and policy monitoring can take place. We would urge you to establish a team within the health/ social care statutory set up to undertake this work. The objectives of the NOSP team are

- oversee the implementation of ReachOut

- commission appropriate research

- coordinate suicide prevention activity

- consult widely and regularly with interested organisations

Additionally we have found that the statutory obligation on the HSE (through NOSP) to report to the Houses of the Oireachtas on suicide prevention activities in the previous year has been helpful in focussing our efforts. We produce an annual report for this purpose which is available on our website (hard copy enclosed)

We would support the extension of the current all island suicide prevention action plan for the delivery of practical actions to prevent suicide. In our view there is no need to change the current strategies north and south, but it is important that we continue to work together and evaluate, jointly if possible, the impact of the actions/recommendations set out in the two documents.

Geoff Day

Director

HSE National Office for Suicide Prevention

15.10.07

All-Ireland Suicide Prevention Action Plan – Position Paper

1. Training

2. ROs and Coordinators meetings

3. MediaWatch/Volunteers/Guidelines

4. Men’s Health Forum

5. Registry of Self Harm

6. Suicide Data Collection Arrangements

7. Awareness campaign

8. CAWT

9. Implementation Groups

10. XXIV Biennial Congress of the International Association of Suicide Prevention

1. Training

Awareness Training

Opportunity: A basic awareness training programme in suicide prevention has been developed jointly by the HSE Resource Officers for Suicide Prevention and Suicide Awareness Coordinators in Northern Ireland. An opportunity now exists to assess the suitability for the roll-out of this awareness training to community groups throughout Ireland, north and south.

Delivery Partners: National Training Officer of the HSE NOSP (appointment is due) and possible designation of Awareness Coordinator in Northern Ireland.

Timeframe: November 2006 – ongoing.

Outcome: Common standardised awareness training delivery to communities north and south

Skills-based Training

Opportunity: Both jurisdictions have a number of trainers in the ASIST (Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training) Programme and an evaluation tool is currently being developed. It is recommended that a common evaluation tool is utilised for all ASIST workshops throughout Ireland.

Delivery Partners: NOSP Assistant Research and Resource Officer and designated ASIST Training coordinator in Northern Ireland.

Timeframe: November 2006 – ongoing.

Outcome: Programme evaluation to inform future skills-based training needs.

2. Resource Officers and Awareness Coordinators meetings

Opportunity: The third cross-border meeting of Resource Officers for Suicide Prevention and their Northern Ireland counterparts took place in Monaghan in April, 2005. It is recommended that this meeting be continued as an information-sharing meeting.

Delivery Partners: HSE Resource Officers and NI Suicide Awareness Coordinators with the support of the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, and the National Office for Suicide Prevention of the Health Service Executive.

Timeframe: March 2007 and annually thereafter.

Outcome: Economies of scale in suicide prevention practices and programmes, information sharing and a cross-border peer support network.

3. Media Monitoring / Volunteer Programme / Media Training

Opportunity: A new media monitoring campaign, Headline, has just been launched as a partnership project between the NOSP and an alliance of voluntary mental health organisations in the south. Furthermore, as part of the implementation of the Reach Out strategy the NOSP plans to develop a panel of volunteers who have been affected by mental health issues and/or suicidal behaviour to respond to the media on these issues following training and with ongoing support. It is envisaged that the development of such a network of volunteers, both in NI and ROI, will facilitate access to media training courses and provide an incentive to editors and sub-editors to develop links with the NOSP, DHSSPS and other partner organisations. It is proposed that the development of the campaign, the network and the media training should adopt an all-island approach as far as possible / practical.

Delivery Partners: Headline, NOSP, HPA, DHSSPS, NUJ, Association of Editors

Timeframe: Headline campaign - October 2006. Volunteer Programme and Media Training – June 2007.

Outcome: common messages and standardised safe reporting practices in relation to suicidal behaviour.

4. Men’s Health Forum

Opportunity: both Reach Out and Protect Life highlight male suicide as an area of particular concern, requiring dedicated and specific actions for prevention. The Men’s Health Forum in Ireland provides a unique vehicle to develop and implement such actions on an all-island basis. The Men’s Health Forum in Ireland (MHFI) is a voluntary network of individuals and organisations proactively highlighting and addressing key men’s health issues in Ireland, including mental health and suicide. It is proposed that we should consider appointing a mental health promotion and suicide prevention officer to coordinate suicide prevention activities for men throughout Ireland.

Delivery Partners: NOSP, DHSSPS and Men’s Health Forum.

Timeframe: March 2007 – ongoing.

Outcome: coordinated suicide prevention activities for men through a dedicated post.

5. Registry of Self-Harm

Opportunity: the National Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm was established in 2001 and reached full coverage of Accident and Emergency Departments throughout the south of Ireland by 2005. The Registry reports annually on the number and rate of presentations for deliberate self-harm in each hospital according to age, gender, method and type of care received. Service planning is informed by the Registry report. It is proposed that the Registry should be piloted, and then rolled out on a phased basis in Northern Ireland providing all-island data on self-harm.

Delivery Partners: National Suicide Research Foundation, NOSP and DHSSPS.

Timeframe: October 2006 (planning meeting), pilot site in Northern Ireland from January 2007.

Outcome: Comparative all-island data on self-harm to assist in evaluating current service provision models and plan future service developments.

6. Suicide Data Collection Arrangements

Opportunity: It is anticipated that the successful implementation of both Strategies will result in reduced stigma surrounding the issue of suicide, and this in turn will likely lead to an increased number of deaths being officially recorded as suicide. Such increases, while being an inevitable outworking of a successful implementation process, would make it difficult to report objectively on the achievements of our respective Strategies. The development of standardised recording arrangements would therefore provide us with the opportunity to make accurate and meaningful statistical comparisons with a neighbouring jurisdiction. The establishment of an Island wide confidential enquiry into deaths by suicide may provide us with the method for achieving this harmonisation.

Delivery Partners: DHSSPS, NOSP, NI Coroners Office, National Suicide Research Foundation.

Timeframe: November 2006 - Ongoing

Outcome: Standardised suicide recording throughout the Island of Ireland.

7. Awareness Campaign

Opportunity: Both Strategies highlight the need to develop major information campaigns which aim to de-stigmatise and promote positive mental health. The Health promotion Agency (HPA) in Northern Ireland has recently published details of extensive research into this issue, and it is intended that these findings will provide the basis for the forthcoming campaign in Northern Ireland. As both jurisdictions have a similar delivery timescale for their campaigns, an opportunity exists to share the research findings with NOSP and HSE with a view to developing a joint awareness campaign

Delivery Partners: DHSSPS, HPA, NOSP, and HSE

Timeframe: November 2006 – March 2007

Outcome: An agreed message being delivered across the many shared media outlets in both jurisdictions

8. Co-operation and Working Together (CAWT)

Opportunity: CAWT is a cross border body formed in 1992, and it currently operates within the North Western/Eastern HSE (ROI) and the Western and Southern HSSB’s (NI) boundaries. CAWT is dedicated to realising the full potential of cross border co-operation in Health and Social Care in order to improve the well-being of the resident population. The potential therefore exists to expand the number of projects managed by CAWT and to enhance its Health and Social Care co-ordination role in the border regions, and potentially further afield.

Delivery Partners: SSIB, CAWT, NOSP, HSE and DHSSPS

Timeframe: November 2006 – Ongoing

Outcome: The provision of standardised and seamless Health and Social Care services in the border regions, and potentially further afield.

9. Implementation Groups

Opportunity: Implementation of the “Reach Out” and “Protect Life – A Shared Vision” Strategies is at a similar stage, and close co-operation and information sharing already takes place between the respective implementation bodies in both jurisdictions. The opportunity exists to formalise this co-operation by offering reciprocal membership of the Suicide Strategy Implementation Body (NI) and the National Advisory Group (ROI) to the NOSP and the DHSSPS respectively. .

Delivery Partners: DHSSPS, NOSP, SSIB, and National Advisory Group.

Timeframe: October 2006 – Ongoing

Outcome: Enhanced information sharing in relation to the implementation of the respective Suicide Prevention Strategies.

10. XXIV Biennial Congress of the International Association of Suicide Prevention

Opportunity: The XXIV Biennial Congress is being hosted by the Irish Association of Suicidology (IAS) in Killarney, from 28 August 2007 to 1 September 2007. The congress is a major international event and it is anticipated that it will attract between 400-500 delegates. There will be a major symposium on Suicide Prevention in Ireland, North and South, during the congress, and this will allow us the opportunity to showcase the implementation of both Strategies to an international audience.

Delivery Partners: IAS, NOSP, DHSSPS, HPA.

Timeframe: November 2006 – September 2007

Outcome: Evaluation and testing of the implementation process for both the “Reach Out” and “Protect Life” Strategies against an international audience.

Ulidia Integrated College

Before I begin, I wish to ask for clarification concerning ‘Protect Life: A Shared Vision’ – Preventing Suicide Actions in the Promoting Mental Health Strategy and Action Plan, Annex 1, Page 67.

I quote,

“Action 21: DE and DEL in partnership with Education and Library Boards, Schools, Youth Council for NI, HPA and HSS Boards will implement programmes on awareness of suicide for teachers and youth leaders.

Target Date: April 2004

Objective: Achieved.”

I am at a loss - as a teacher - to know what Action 21 is or what it accomplished. I would like to discover how many teachers know anything about it. Certainly everything I have learned in relation to suicide, I have learned through my own initiative. How has this Action been “achieved”?

My Response

I wish to respond to the committee in two sections:

- Counselling in Schools

- Effective Teaching concerning Mental Health Issues in the Classroom

I fully support improved links between education and health. The Health professionals I have met are very approachable, such as Colm Donaghy, Chief Executive of the Southern Area Trust and Head of the Taskforce into Prevention of Suicide, in Northern Ireland. However, the Department of Education remains aloof and bureaucratic.

I think the approach to Mental Health in schools needs to change dramatically. The Department of Education needs to speak with principals and teachers rather than be cut off from schools and unresponsive. Whilst great things may be afoot behind closed doors concerning this issue, schools are not made aware of them, nor are teachers included in the process.

Counselling

All schools have a Pastoral Care System; some are more effective than others. The Pastoral Care Coordinator is usually at Vice Principal or Senior Teacher level. These senior teachers administer the pastoral care system and ensure that the procedures are followed. However, they are not and should not be counsellors. A pupil cannot be expected to bare his soul to someone who may have to teach him the next day and perhaps reprimand him for not having a homework done. Counsellors should be independent, and should have a different and very productive relationship with pupils, which is wholly pastoral.

This year, commencing September, 2007, Contact Youth has been awarded a contract to offer counselling in schools. Many people not involved in education greeted this news with delight. Counsellors in every school! Wonderful! However the reality is very different. This is at most a token gesture.

It is my understanding that some schools may have a Contact Youth counsellor for one – three hours, at most once a week. Other schools have NSPCC counsellors who work part-time in schools, for a few afternoons /mornings and have had these counsellors for some years. A very few schools have full-time counsellors.

The fact is all schools need a counsellor present, every day, solely responsible to the pupils in that school.

The cost of such counselling would be worthwhile on two counts:

- the human right to a healthy, happy life

- the resulting reduction in mental health problems among the adult population in the NHS.

When pupils experience problems, these should not be deferred until a counsellor happens to come into the school, if one does come. Problems need dealt with as these arise. Problems which are not addressed grow and cause great unhappiness in adulthood and can profoundly affect the next generation of children, born to a parent with a mental health problem.

‘Protect Life: A Shared Vision’ – Annex 4, page 79 - states that “Research has shown that a psychiatric disorder is present in around 90% of suicide victims.” (Cavanagh et al 2003).

I believe that young people often lack the strategies to cope with situations such as death, broken relationships, et cetera, and that if their problems are not resolved or if they do not get help, they can become more deeply depressed. Many distressing problems can arise from poor parental skills and these can have devastating effects on the children. I would like to see more research done about psychiatric disorders and whether these result from long-term depression, arising from lack of coping strategies. Often a counsellor can advise pupils how to cope with the difficulties they encounter if she is accessible when the pupils need her.

I hope the provision of a few counsellors in some schools for a few hours does not lead to the Department of Education ticking the box ‘counselling in schools - done’ and forgetting to expand and improve the system.

The target should be to employ a counsellor in every school, primary and secondary, during term times only.

Moreover, effective research needs to be carried out, costing done and projections made on the savings counselling would bring in relation to the NHS and expenditure on mental health issues.

I would like assurance that this research will be done urgently, if it is not already underway.

It is also my understanding that when the provision for Contact Youth counsellors was introduced, the counsellors reported directly to their supervisors and not to the Headmaster or Child Protection Officer in the school. I think this has been redressed but why was it not foreseen? All counsellors should have to report to the Headmaster/Child Protection Officer where a pupil has disclosed self-harm, abuse or where suicidal thoughts have been expressed. No pupils should be allowed to leave school without their safety being safe-guarded by a responsible adult.

Counsellors in schools often have limited access to senior management and can work on the periphery of school life; they can be hidden away if the principal stigmatises Mental Health, and their counselling rooms can be very small and barren. Such attitudes and conditions must be redressed urgently. Tokenism will not suffice to bring about the changes in attitude and provision necessary to secure a high standard of mental health care in Northern Ireland.

Pastoral Care and Counselling in Ulidia Integrated College –

A Model of Excellence

In my school, Ulidia Integrated College, in Carrickfergus, we have a full-time counsellor paid for by the college. She works from 8.50 am – 4.00 pm, or later if the need arises.

Our counsellor dislikes the term ‘counsellor’ and she is known as the ‘Student Support Officer’ as this enables pupils to realise that their visits to her can be about little issues, not just a major crisis in their lives. Pupils can drop in for a chat at break time or over lunch time or arrange appointments during class time for 35 minutes on a one-to-one basis, weekly or fortnightly depending on their need.

The room used by the Student Support Officer is known as the Group Room. It is warm, bright and colourful, with posters and leaflets on the wall about counselling issues and help-lines/organisations. There are books and leaflets available about organisations that can assist pupils. There are plants in the room, a carpet and three green leather settees; the blinds on the windows allow pupils to see out but not into the room. The Group Room is situated opposite the Resource Centre and the foyer the rooms share has comfortable chairs and bright, colourful posters on the walls.

It is an area of the school that is safe, quiet and well used. Few pupils mind anyone seeing them talking with our Student Support Officer because it is the norm to do so.

Our Student Support Officer is well qualified and extremely well respected by the teaching staff. She has a key role in the college and meets regularly with the Pastoral Care Coordinator and the Heads of Year. She is the designated Deputy Child Protection Officer in the school. (The Vice Principal is the designated Child Protection Officer.) She attends Senior Management Meetings and has input into management decisions as she is the person with most knowledge concerning the welfare of the 530 pupils in the college. This involvement at management level is probably unique and illustrates the importance attached to her role by the Headmaster.

‘Protect Life – A Shared Vision’ – page 42 – states that all schools should protect children from bullying and Health and Social Services’ Trusts should have a buddying/mentoring type scheme in place by 2008.

Our Student Support Officer has trained and worked with Childline. She has introduced a Mentor Scheme into Years 13 and 14 and these pupils receive training from Childline. They are able to mentor Year 8 and 9 pupils and help them resolve the difficulties they face or else direct these pupils to seek appropriate assistance from staff or parents. The Sixth Form pupils love being mentors and see it as a badge of honour; it is not available to all Sixth Formers. Pupils must be appropriate in their attitudes and dedication to others. The Student Support Officer picks the mentors. They are trained (as are all teachers and staff in schools in Northern Ireland), in Child Protection and they know that a pupil cannot be offered confidentiality when they could be at risk of harm from themselves or from others. They report directly to the Student Support Officer if a pupil discloses something of concern - as do all staff.

The Headmaster, the Pastoral Care Coordinator, the Student Support Officer and the staff and pupils at Ulidia Integrated College have created a whole school ethos which is anti-bullying and every class room displays an anti-bullying poster created by the pupils. This gives pupils ownership of the ethos and, as we are an integrated college, all pupils are aware of avoiding terminology that is racist or bigoted. Our mission statement is: ‘Educating together, Catholics and Protestants and those of other religions, or none, in an atmosphere of understanding and tolerance to the highest academic standards.’ This whole-school ethos is essential in every school. It is fostered by discussing issues openly in an atmosphere of tolerance. Too many schools avoid discussing controversial issues, thus restricting pupils’ ability to expand their thinking.

At Ulidia, the Headmaster takes the four Year 8 classes for ‘Ulidia Studies’ and they discuss issues that are in the news or which arise naturally and interest them. On one occasion a Year 8 pupil was speaking with the late Mo Mowlam while she visited the school, and he told her that he had discussed disarmament in Northern Ireland in Ulidia Studies. She was most impressed! Of course, the point is that pupils who feel that their opinions are valued and respected don’t bully or tolerate bullying behaviour in others. All pupils in Ulidia know that any signs of bullying will be dealt with and never ignored.

The Education and Training Inspectorate said of the college in 2007,

“There are significant strengths in many aspects of the arrangements for pastoral care and child protection, which include:

- the well resourced and high quality counselling service;

- the effective Students’ Council;

- the well-embedded anti-bullying programme; and

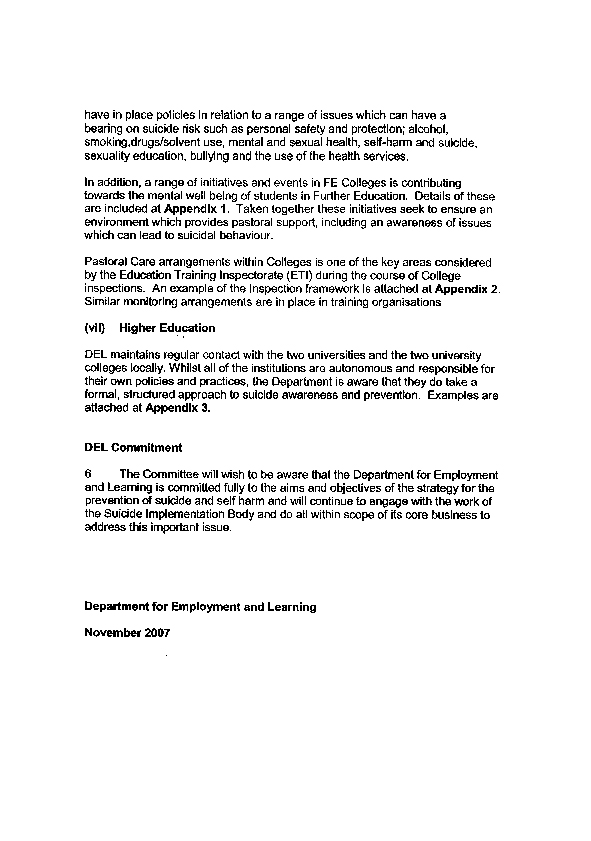

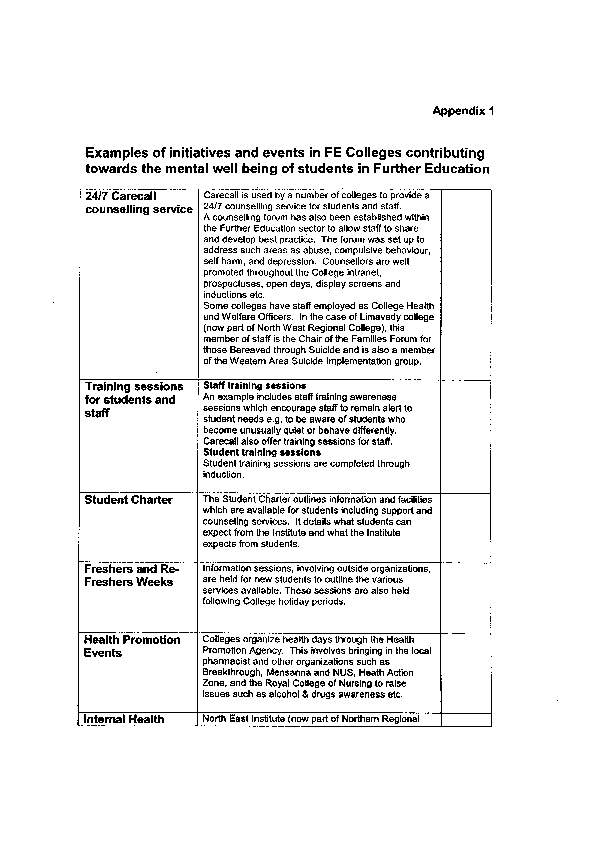

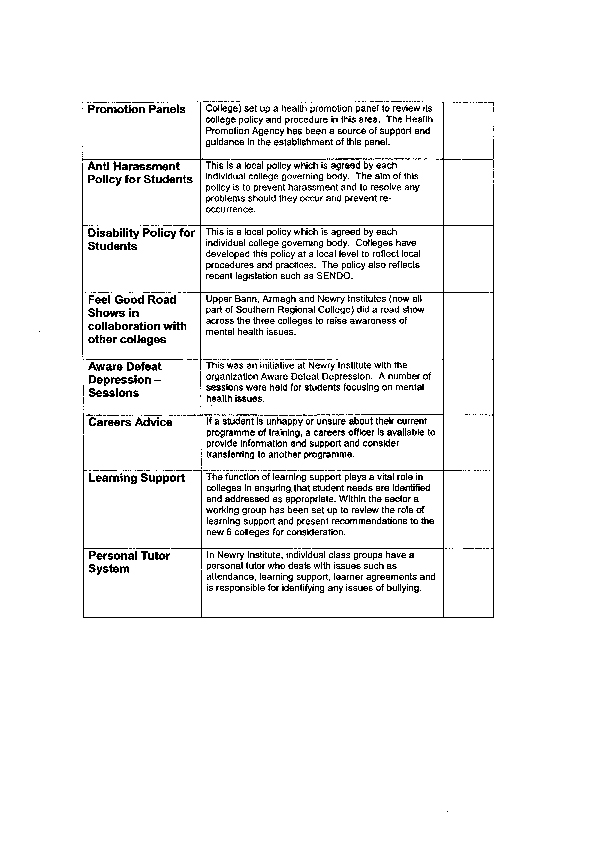

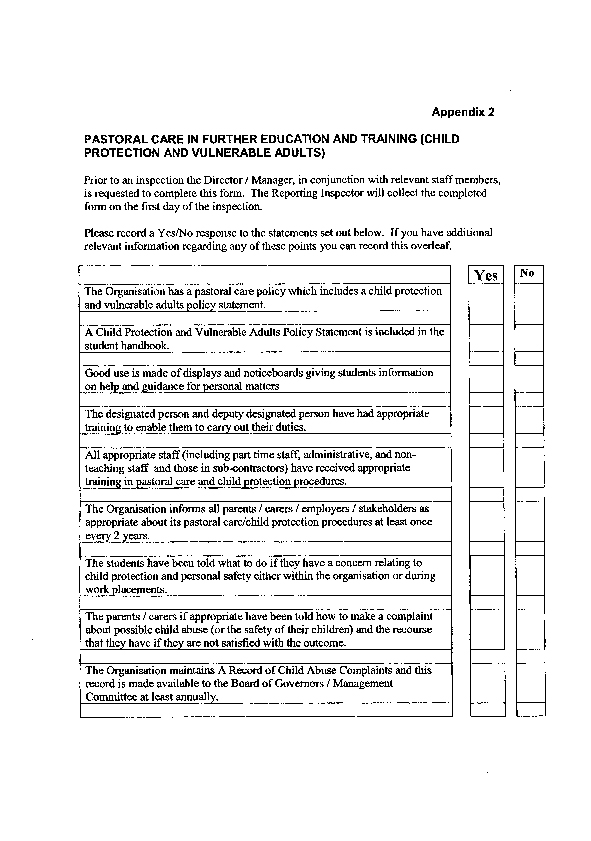

- the effective mentoring system.”