Comments on Review of Competitiveness of Northern Ireland

Dr Graham Gudgin, Centre For Business Research, University of Cambridge and Neil Gibson, Director, Oxford Economics.

We welcome the wide-ranging report on economic competitiveness from Sir David Varney and his team. The early days of a new and potentially stable devolved administration in Northern Ireland is an opportune time to reassess what needs to be done to close the wide gap in GVA per head between NI and both GB and the Republic of Ireland. We strongly agree with the Review’s emphasis on the need for economic reforms and in particular the suggestion for an annual and independent economic competitiveness report.

Summary of Critique

In summary, our reaction to the Review is that it contains a substantial number of recommendations, many of which we support, but which we believe would not, in aggregate, make a significant difference to Northern Ireland’s economic position relative to the rest of the UK. In other words, even if all of these recommendations were to be put into practice, based on our long and deep experience of research into the NI economy, we would expect the gap in GVA per head between NI and GB to remain almost as wide as it now. Few of these recommendations include any measure of expected impact. In addition there are downside risks to some recommendations which are not discussed in the Review. While recommendations relating to social security reform might have social and long-tern economic advantages they could damage the economy in the short term. Similarly, the recommendation that the Executive uses its powers to reduce public sector pay below the UK average could, if implemented, lead to damaging consquences for the NI economy.

The DFP Committee should recognise that Sir David and his Treasury team have only limited expertise in the specialised discipline of regional economic analysis, and this is reflected in the lack of success which the present government has had in stemming the growing productivity gap between the English regions for which they have direct responsibility. The productivity gap between SE England and other English regions has widened greatly while the Blair-Brown government has been in office and their main institution for regional economic development, the Regional Development Agencies, are widely regarded in academic circles as ineffective.

Underlying Economic Analysis

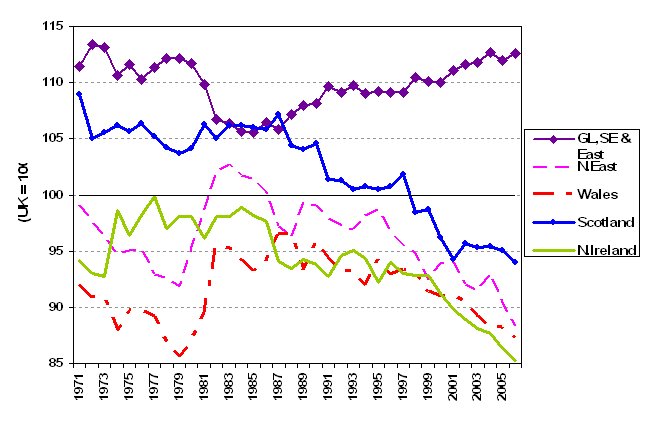

We regard the economic analysis, on which the recommendations are ostensibly based, as largely conventional with little that would not be well known to local economists. It is however essentially shallow, relying to too great an extent on assumption and assertion rather than detailed research. In particular it fails to place NI within the important context of economic trends in other UK regions. As a result it downplays or misses some of the strongly divergent pressures on peripheral economies within the UK which have proved very difficult to counteract. There is no discussion, for instance, of the strong divergence in relative productivity (GVA per employee) that has affected all UK regions over the last 20 years, and has affected Scotland, Wales and North East England as much as NI (see chart 1 below).

These divergent trends reflect the developing strength of the London and SE England economies based on national and internationally competitive financial and business services. Except for occasional outliers in Edinburgh or Leeds it has been difficult for the northern and peripheral regions to replace their declining manufacturing bases with internationally competitive service sectors. The strength of SE England is underpinned by its ability to attract a disproportionately large share of the UK’s skilled workforce in a context in which that skilled workforce has remained too small. It has been particularly difficult in NI, and exceptionally difficult in NI outside Belfast, where the absence of a history of nationally or internationally traded services leaves only a very limited base on which to build. We see little in the Review’s recommendation that will address this fundamental reality.

Chart 1 Divergent productivity in UK regions. GVA per Employee 1971-2006

Sources of Data; Regional Accounts GVA, ABI employment and LFS self employment.

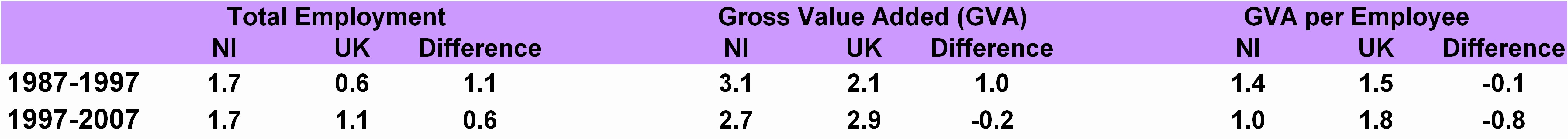

The Review appears to regard the NI economy as performing reasonably well since the end of the ‘Troubles’ but requiring additional measures to meet the remaining challenges. This again misses the depth of the problem. In fact the NI economy has performed less well on most key measures over the last ten years to 2007 than in the decade prior to 1997 (see Table 1 below). Similarly, NI’s share of inward investment jobs coming into the UK is lower now than prior to the pre-Belfast Agreement (see Chart 2 below). If the NI economy has performed less well in both absolute and relative terms since 1997 there

Table 1 Annual Average Growth Rates (% per annum)

Sources of Data; Regional Accounts GVA, ABI employment and LFS self employment.

Chart 2 Northern Ireland Share of Jobs Promoted in Inward Investment Moves into the UK

Source of Data: InvestUK, UKTL, ONS

are clearly strong forces at work, and we believe that the Review completely underestimates their strength. As a result the Review is, in our view over-confident on the likely impact of the proposed reforms.

Skills

We strongly agree with the Review’s contention that ‘an appropriately skilled workforce is key to economic competitiveness’ (page 39). The Review recognises the strengths of the NI schools system and the good results it achieves, and also recognises that any improvements in school attainment will take decades to filter through to the workforce at large. However, the Review fails in our view to recognise why skills levels in the NI workforce as a whole are so poor in the context of a favourable education system. Examination results have been better in NI since the late 1960’s when NI retained its selective secondary school system while most of GB adopted a comprehensive system. Despite this favourable achievement over almost 4 decades, the stock of skills in NI remains the least favourable of any UK region.

A combination of a good flow of skills from the schools with a poor stock of skills in the current workforce means that many of the best qualified have left NI, while few high skilled people have moved in and the less qualified have remained. The Review gives far too little consideration to the likelihood that it is the demand for skills from local employers that is the root cause of the poor skills structure. Without well paid local jobs to take up, many of the best qualified have left NI, and there has been little to attract well qualified outsiders. The emphasis in chapter 3 of the Review on improving the supply of skills rather than the demand largely misses the point, and again reflects the way in which the Review underestimates difficulties and is over-confident on the potential impact of government initiatives.

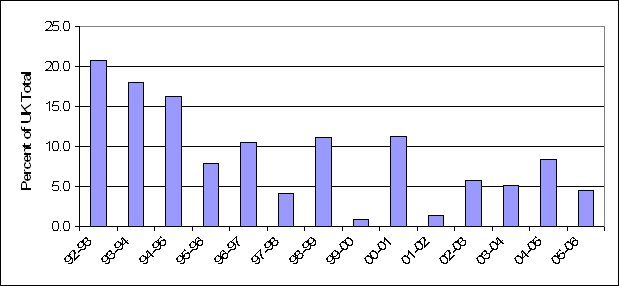

The Review does note the good news that the skills mix is better among younger workers than older workers both absolutely and relative to GB, but it also reports the views of some consultees that too many young graduates remaining in NI are employed in low wage call centres. This nevertheless presents an opportunity since research shows that regional productivity levels are closely related to the proportion of employees who are graduates working in the private sector and particularly in the financial and business services sectors (see Chart 3 below). In contrast, graduates working in the public sector appear to have no influence on local productivity levels.

Chart 3 Productivity Across UK Counties is Strongly Related to Graduates in the Private Sector

Source of Data: Census 2001; regional Accounts workplace data. Greater Belfast is highlighted as a square and the rest of NI as a circle.

What the Review cannot do is to recognise that the quickest and surest way to improve the qualifications and productivity in NI is to attract new international companies for instance through adopting the Republic’s key policy of low corporation tax. Having rejected this in his previous report, Sir David is left with no effective means of changing the demand for jobs and falls back on a few, largely peripheral, recommendations on the supply of skills. In our view these will make little difference even if fully implemented. The Review also underestimates the shortage of skills in the UK and hence the continuing need for SE England to attract skills from all other regions. (In our view Chart 3.1 in the Review gives a distorted view of the skills structure in the UK and gives a very different impression from similar charts produced by BERR or ONS).

Employment

The Review rightly points to the low employment rate in NI as an important cause of low GVA per head relative to GB. NI has one of the lowest employment rates of any UK region despite having the best record of job creation of any region over several decades. The Review also correctly points to long term sickness and incapacity benefit as the main reason for the relatively large number of inactive people of working age in NI. In this respect NI resembles parts of GB with similarly high dependency on incapacity benefit. These include former mining areas but also Merseyside and Glasgow. These are all areas where, historically, large numbers of unemployed people were allowed or even encouraged to transfer from unemployment to incapacity benefit, allowing a culture of benefits to develop. Together with Disability Living Allowance, Housing and other ‘passport’ benefits, aggregate incomes from incapacity benefits can be higher than from work.

Chapter 2 of the Review follows the UK government’s current priorities in suggesting a range of measures to get incapacity benefit recipients back to work. Since NI tends to reflect measures affecting social security claimants as part of the parity principle on social security rates, it is likely that most such measures would be adopted anyway. Proposed social security reforms have many positive aspects, it seems doubtful that they will do much to reduce NI’s low level of GVA per head relative to GB. The most likely outcome is a transfer of poorly qualified people from benefits into low paid work. Employment rates would rise but at the expense of falling productivity in the NI economy. Although desirable in many ways this would do little to change NI’s relative productivity.

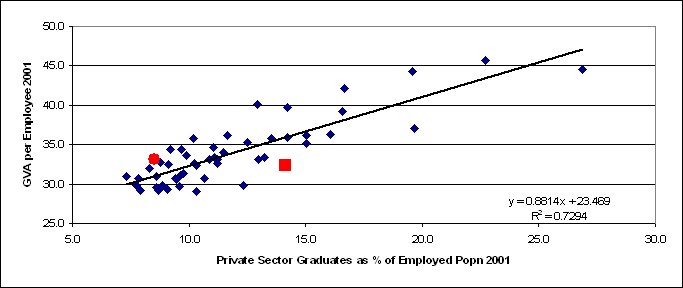

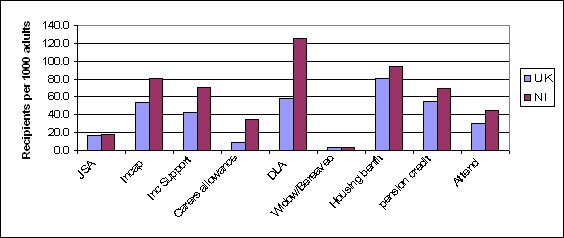

What the Review also does not highlight is the danger to NI public expenditure if NI was to adopt such a programme more rapidly than in GB. The income accruing to benefit recipients is an important part of the public expenditure subvention, and a rapid transfer of benefit recipients into low paid work could diminish the subvention without materially strengthening the economy. Through adopting social security reforms at the same pace as in GB, NI stands to gain proportionately from the reallocation of the funds freed up from the social security budget. NI has a level of benefit claimants which is 50% higher than GB, and one which is higher for all benefit types (see Chart 4). As a result any reduction

in the number and income of claimants could reduce the almost £6 billion per annum of the social security payments flowing into the NI economy. While there are sound social and financial reasons for wishing to reduce numbers of benefit recipients, any reforms must be approached with care and should match measures in GB. However reforms which match those in GB will do relatively little to close the gap in GVA per head.

Chart 4 Social Security Benefit Recipients per Thousand Adults 2006

Sources: Social Security Agency NI. DWP.

Investment

We agree with the Review’s assessment on the importance of investment, but find its judgement that NI performs well in attracting inward investment once again superficial. In the pre-Troubles period NI regularly attracted 25% of UK jobs in mobile companies originating both from within the UK and abroad. Today the figure is around 5% and as Chart 2 showed this is a lower share than in the 1990’s. Since NI’s share of UK government expenditure on regional development (RSA, SFI etc) is around 20% each year, a 5% share of inward investment jobs is hardly high. The Review underplays the difficulties in attracting service sector investment to NI in a highly competitive world where tax rates and labour costs are often much more advantageous elsewhere. While the UK as a whole has done well, this advantage is diminishing as corporation tax rises towards the top of the concerns of international companies. In the absence of much constructive to say, the Review falls back on platitudes recommending a further review, and on minor issues including the ‘honing of its offer’ (p.59).

Innovation

We support the Review’s view that the low level of R&D spending in NI is appropriate to its size and industrial structure. The recommendations made in the Review are likely to be helpful but it is difficult to see that they will result in substantially higher levels of R&D spend, or that this will make a material difference to productivity levels in NI. The Review fails to discuss more radical approaches including a major expansion of higher education in NI, and an end to the current situation in which NI ‘exports’ well qualified students to ‘university rich’ regions like Scotland. The obvious approach of attracting more international companies to NI in R&D-intensive sectors, as has been successfully done in the Republic, is once again not discussed because of Sir David’s opposition to corporation tax reform (which itself reflects the PM’s well-known views on this matter).

Enterprise

The Review takes a sensible, and in this case unconventional, view that there are few significant differences between NI and GB in the level of business start-ups (p85). The Review also notes that failure rates are lower in NI, a fact that we ascribe to the high level of government support and subsidy in NI. Once again the recommended actions are small-scale and unlikely have a substantial impact on either company formation or company growth. Changing formation rates is difficult, and the major initiative to raise the low rates in Scotland was a complete flop. More radical approaches are needed, especially in respect of generating large companies from local start-ups since NI is especially deficient in this area. Iceland appears to have succeeded in generating successful firms in part through sending students to US business schools.

Public Sector

The Review, recognises, as do most commentators, that NI’s level of public spending is large, although they do not point out that an important part of this is connected with social security benefits. UK Government reforms, for instance on tax credits, have inflated the ‘subvention’ to NI. While we agree that much can be done to make parts of the public sector more efficient, it is difficult to see how this would reduce the relative size of public spending which is determined by the Barnett Formula. Savings in one area would lead to high spending in others. Neither could spending on industrial support be increased since the key constraint here is EU State Aid rules. The most contentious recommendation is the suggestion that the Executive use its power to restrict public sector pay. Lower public pay in NI would accelerate net out-migration of mobile, well-qualified people. Nor is it obvious that the private sector would gain since tax rates would not change, and in addition there has never been any systematic evidence of crowding out of private sector recruitment. Indeed under-employment of graduates in low paid call centre jobs suggests that there is still an excess of well qualified people. Once again lower pay would not reduce public spending. It would instead lead to higher levels of public sector employment.