Session 2010/2011

Third Report

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Report on the Executive's Draft Budget 2011-15

Volume 3

Written Submissions, Research Papers and Memoranda

Ordered by The Committee for Finance and Personnel to be printed 16 February 2011

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Report: NIA 44/09/10R

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Finance and Personnel is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department of Finance and Personnel and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has the power to;

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Finance and Personnel.

Membership

The Committee has eleven members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of five members. The membership of the Committee during the current mandate has been as follows:

- Mr Daithí McKay (Chairperson)1

- Mr David McNarry (Deputy Chairperson)2

- Dr Stephen Farry

- Mr Paul Frew3

- Mr Paul Girvan4

- Mr Simon Hamilton

- Ms Jennifer McCann

- Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

- Mr Adrian McQuillan

- Mr Declan O'Loan

- Ms Dawn Purvis

1. Mr Daithí McKay replaced Ms Jennifer McCann as Chairperson on 19 January 2011, having replaced Mr Fra McCann on the Committee on 13 September 2010. Ms McCann replaced Mr Mitchel McLaughlin as Chairperson on 9 September 2009.

2. Mr David McNarry was appointed Deputy Chairperson on 12 April 2010 having replaced Mr Roy Beggs on the Committee on 29 September 2008.

3. Mr Paul Frew joined the Committee on 13 September 2010; Mr Ian Paisley Jr left the Committee on 21 June 2010 having replaced Mr Mervyn Storey on 30 June 2008.

4. Mr Paul Girvan replaced Mr Jonathan Craig on 13 September 2010; Mr Jonathan Craig had been appointed as a member of the Committee on 13 April 2010. Mr Peter Weir left the Committee on 12 April 2010. Mr Peter Weir had replaced Mr Simon Hamilton as Deputy Chairperson on 4 July 2009. Mr Simon Hamilton replaced Mr Mervyn Storey as Deputy Chairperson on 10 June 2008.

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in the Report

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in the Report

ACNI Arts Council Northern Ireland

A&E Accident and Emergency

ALB Arm's Length Body

AME Annually Managed Expenditure

AMU Assets Management Unit

ASB Aggregated Schools Budget

BBA British Bankers' Association

CART Capital Assets Realisation Taskforce

CBI Confederation of British Industry Northern Ireland

CDO Collateralised Debt Obligations

CEF Construction Employers Federation

CFG Central Finance Group

CFP Committee for Finance and Personnel

CIF Construction Industry Forum

CSR Comprehensive Spending Review

DARD Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

DCAL Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

DE Department of Education

DEL Departmental Expenditure Limits

DEL Department for Employment and Learning

DETI Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

DHSSPS Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

DLA Disability Living Allowance

DoE Department of the Environment

DoJ Department of Justice

DRD Department for Regional Development

DSD Department for Social Development

DWP Department of Work and Pensions

EDP Efficiency Delivery Plan

EIB European Investment Bank

E&LB Education and Library Board

EQIA Equality Impact Assessments

ERINI Economic Research Institute of Northern Ireland

ESRI Economic and Social Research Institute

ESS Enterprise Shared Services

ETI Enterprise, Trade and Investment

EU European Union

EYF End of Year Flexibility

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FSB Federation of Small Businesses

FSME Free School Meal Entitlement

FTE Full time equivalent

GB Great Britain

GP General Practitioner

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GVA Gross Value Added

HE Higher Education

HLIA High Level Impact Assessment

HM Her Majesty's

HMT Her Majesty's Treasury

HR Human Resources

ICT Information Communication Technology

ICTU Irish Congress of Trade Unions

IFS Institute for Fiscal Studies

IMF International Monetary Fund

IoD Institute of Directors

ISNI Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland

LPS Land and Property Services

JESSICA Joint European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Area

MAC Metropolitan Arts Centre

MLA Member of the Legislative Assembly

NAMA National Assets Management Agency

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

NI Northern Ireland

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICMA Northern Ireland Childminding Association

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NICVA Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action

NIFHA Northern Ireland Federation of Housing Associations

NIHE Northern Ireland Housing Executive

NILGA Northern Ireland Local Government Association

NIMFG Northern Ireland Manufacturing Focus Group

NIPSA Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance

NITA Northern Ireland Theatre Association

NIW Northern Ireland Water

OCA Office Cost Allowance

OFMDFM Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

PAC Public Accounts Committee

PEDU Performance and Efficiency Delivery Unit

PfG Programme for Government

PFI Private Finance Initiative

PMS Presbyterian Mutual Society

PPP Public Private Partnerships

PRONI Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

PSA Public Service Agreement

PSE UK Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK Project

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

PSO Public Service Obligations

PwC PricewaterhouseCoopers

QUB Queen's University, Belfast

RoI Republic of Ireland

RRI Reinvestment and Reform Initiative

SCS Senior Civil Service

SEN Special Educational Needs

SHDP Social Housing Development Programme

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SME Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

SOU Special Olympics Ulster

SROI Social Return on Investment

SSRB Senior Salaries Review Body

STAR Skills, Training and Reinvestment

UK United Kingdom

USA United States of America

Appendix 6

Written Submissions

The Methodist Church in Ireland - Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans

Action for Children to Finance Minister

9 September 2010

Mr Sammy Wilson, MP, MLA |

Action for Children Northern Ireland |

Dear Minister

Action for Children is keen to engage constructively with the Northern Ireland Executive in order to share our impact evidence and solutions to help with the delivery of efficiencies to the economy. Following our letter to you (5th March 2010) about the NI Government Department Spending Review 2010/1011, I am writing to set out Action for Children's input to the Comprehensive Spending Review process in Northern Ireland.

I welcome the opportunities presented to us to engage in dialogue over the reductions to public expenditure and would welcome the opportunity to discuss our evidence as proposals are considered by Ministers pending the outcome of the CSR, determination of the Northern Ireland Bloc grant and preparation of the draft Northern Ireland Budget .

In line with our submission already with the Chancellor George Osborne in July 2010, key points summarised here and outlined in more detail in the enclosed paper:

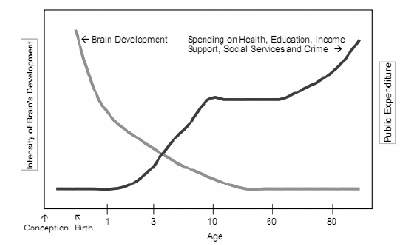

Saving money and transforming lives through early intervention

- Prioritise funding for those early intervention services which are intensive, targeted and founded on a robust evidence base; provided before problems such as chronic neglect of children become intractable with the high financial costs that are then incurred.

Building communities and making existing resources go further

- Protect the investment in Sure Start and Family Support services so that they continue to provide localised, community shaped early-years and family support services that can deliver targeted support to the most disadvantaged people.

Preventing family breakdown

- Prevent family breakdown, avoidable social problems and multi layered financial burden of picking up the pieces by shifting the balance of funding from acute to early intervention services that offered as soon as a problem has been identified.

Designing public services fit for the future

- In such a tight fiscal environment we must urgently transform commissioning to incentivise longterm impact so that less funding does not mean less innovation.

- Develop an impact framework to support those elements, which make the greatest difference: stability of service provision and effective professional relationships.

More than ever, we have a responsibility to be clear that the public money we are entrusted to spend has a demonstrably effective and efficient return on its investment. At Action for Children such accountability is central to our work and we continue to pioneer methods that allow us to show what impact we are actually making. As you look to apply those principles across government here, I would welcome the opportunity to share our evidence and learning.

At Action for Children, we are committed to protecting the most vulnerable and neglected children, young people and families in our society. We would urge you to ensure future funding decisions are in line with Section 75 requirements and do not have an adverse or disproportionate impact on disadvantaged or vulnerable groups including children and young people and their families.

I hope you find our contribution useful in steering the difficult Spending Review decisions ahead, in preparation for the next Northern Ireland Budget and revised Programme for Government. I look forward to further discussions with your department and colleagues in the Northern Ireland Executive.

I have also written to your colleagues on the Northern Ireland Executive, department Children's Champions and members of the NI Assembly departmental Scrutiny Committees.

Yours sincerely

Louise Warde Hunter

Strategic Director Children Services

Action for Children Scotland & NI

cc: Laura McPolin, Department of Finance

Clerk of NI Assembly Finance Committee

Action for Children's Response to CSR NI

Comprehensive Spending Review and next Northern Ireland Budget

Action for Children's approach is underpinned by the principle of protecting the most vulnerable and neglected children, young people and families in our society.

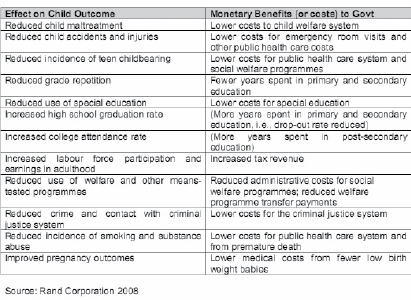

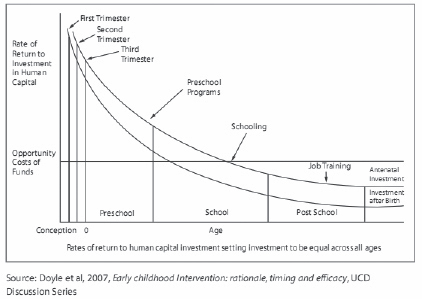

1. Saving money and transforming lives through early intervention

1.1 It is important for the Northern Ireland Executive to demonstrate that it is making a rational decision, not just taking easy choices when making cuts to available public expenditure in Northern Ireland over the next number of years. We believe this represents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to deliver efficiency to the economy by investing in early intervention services, which not only makes economic sense but will transform lives.

1.2 In Northern Ireland around 25,000 children will be born every year. Each one of these children will be full of potential, but right from the start some will struggle - around 1,800 children will already have begun the journey their parents took to the margins of society[1]. Across the UK around one million children are at risk of intergenerational deprivation and neglect which equates to about 51,000 children in Northern Ireland.

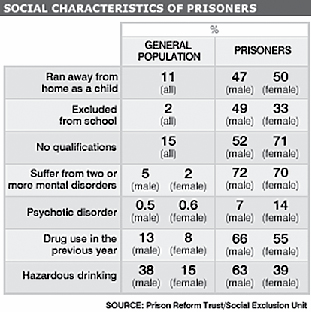

1.3 Almost half the children who demonstrate anti-social behavior in the early years will continue their behaviour into adulthood, ending up as a serial offender. A serial offender will cost society between £1.1 million and £1.9 million over a lifetime. The cost of this criminal activity is estimated at £84 million a year in the UK.

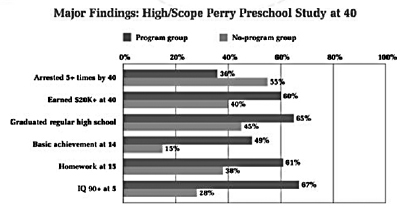

1.4 There is now overwhelming evidence that early intervention works, so we can get better results for the money we spend. Research carried out across the UK for Action for Children by the New Economics Foundation (nef) shows that if we focus on early intervention, the economy could save £486 billion over 20 years[2]. By being smarter in the way we invest, we can release the potential of a new generation. The research included an independent evaluation of three types of services run by Action for Children and showed that, taking into account reduced health costs of children, reduced crime and anti-social behaviour, reduction of costs and care, increased tax revenue through employment and decreased benefits, the services returned between £4 and £9 of social value for every £1 invested in them.

1.5 The Northern Ireland Executive must prioritise funding for children's services and those early intervention services which are intensive, targeted and founded on a robust evidence base; provided before problems become intractable.

2. Building communities and making existing resources go further

2.1 The Northern Ireland Executive must protect investment in Sure Start and family support services so they provide the localised, community shaped early years and family support services that can also deliver targeted support to the most disadvantaged.

2.2 The increased investment in family support services through the Families Matter and Care Matters strategies in Northern Ireland is having a significant, positive impact on vulnerable children as is the funding in Sure Start for children in early years settings. While this investment is welcome, the Executive also needs to recognise that there has been an historic under funding of children's services in Northern Ireland of around 30% compared to other parts of the UK[3].

2.3 Sure Start and family centre-based support services are accepted, accessible assets sitting at the heart of communities experiencing social and economic deprivation in Northern Ireland. Such assets must be reconfigured to harness the return on investment already made (in terms of buildings, people, networks and essential front line support services). Funding for Sure Start and family support provision must be protected to ensure the investment in these local service hubs is not wasted.

2.4 Action for Children is closely involved in developing family support hubs in Northern Ireland through our engagement in children services planning - enabling local needs to be met through the strategic development of services and implementation of Families Matters agenda in Northern Ireland. Co-location of services, such as relationship support, services for children with special education needs, legal services, sexual health clinics, child and family health services and debt advice, efficiencies can be made while also improving focus and impact.

Early Support for disabled children is essential if they are to flourish in a school settingAction for Children's extensive range of services for children with a disability starts from the early years and extends through to young people's transition to adulthood. We understand that services can be delivered effectively in different ways from a number of bases. We aim to ensure all our universal services are available to disabled children and their families, promoting opportunities for them to be included from the earliest age. This includes the support delivered through our Sure Start and family support services. Our four Sure Start services in Northern Ireland work to provide integration and inclusion for children with disabilities within existing services such as with the mobile sensory unit. Our service help with coordinating provision for children and young people with disabilities, providing workers to accompany the children to the centre where they would not otherwise be able to attend on their own. In the longer term such services develops their confidence, skills and experience – all essential to developing school readiness and enhancing longer term education prospects. Our other pre school provision for children with disabilities include: early years crèches, specialist parenting programmes (such as the Little Acorns in Ballymena for parents of children on the autistic spectrum) and access to speech and language services. |

2.5 In order to live up to the promise of delivering to the most vulnerable families, intensive, targeted support services, with evidence of impact, must be embedded within local family support and Sure Start services to truly transform them into community hubs that each out to the most vulnerable and neglected.

2.6 This is not just about efficiencies; this approach will achieve better results by bridging between universal and targeted services, thus addressing the drop off in impact once an intensive intervention has ended. The universal reach is important in terms of avoiding stigma as well as ensuring the earlier identification of emerging problems.

2.7 There are clear advantages for both child outcomes and value for money in being able to offer families a variety of support services from their local Sure Start or family centres. They should be the one-stop shop for children and families, with services tailored and developed in partnership to meet the needs of local families. Through reaching out effectively within local areas, it is possible to take services to families who are unable to access family support services or who need encouragement to do so. To deliver this localism and the flexibility it requires, it will be essential to have sufficient numbers of Sure Start and Family Support Services to have local reach / community profile.

3. Preventing family breakdown

3.1 In order to build sustainable, inclusive communities which will help protect the most vulnerable through difficult times, targeted support must be provided to the most vulnerable families at risk of breakdown.

3.2 This need is ever more pressing given the twin pressures of the need for savings in the current economic climate, and, the increased demand for children's services because of better identification of children in need and increasing numbers of children subject to child protection plans and entering the care system. At a more general level, there are higher demands on health and social care services arising from increasing birth rates and population growth with children much more likely to use services than other groups.

3.3 There is also the growing evidence base of what works, where effective targeted interventions are focused around the pressure points for families and young people. For example, Family Intervention projects, which work with families with multiple and complex problems coast about £8,000 per family. Independent evaluations show that they are successful in 70% of cases, and they reduce levels of physical abuse by 43%. And that's not taking into account the reduction in neglect and suffering of young people at the hands of parent's who can not cope[4].

Action for Children's Early Enervation work in Northern IrelandIn Northern Ireland, Action for Children works with local Health and Social Care Trusts to prevent children from coming into care and getting into trouble. When such children are identified, Action for Children intervenes to strengthen the family unit and enable them to see the positives in their lives including re-engagement with education and preventing offending and anti-social behaviour. These services use a range of interventions including solution-focused brief therapy model of work. Support is offered for an agreed period of time with al interventions regularly reviewed. When work is completed families are tracked to see if progress they made is maintained. |

3.4 We know that rates of family breakdown are significantly higher in families with disabled children; 25% of lone parent families have a disabled child. Disabled children and their families are more likely to live in poverty and so also be adversely affected by an economic downturn because they are at greater risk of living in poverty[5]. It is estimated that 57% of disabled children are living in poverty compared to around 37% of children without disabilities and that it costs three times as much to bring up a disabled child as a non disabled child[6]. Approximately 59% of children living with a chronically ill or disabled parent are poor[7]

3.5 As a leading provider of short breaks services, Action for Children understands how valuable these services are to disabled children and young people and their families. We therefore commissioned research [8] that explored the social and economic value created by short breaks.

3.6 The research concludes that significant savings could be made to the State if short breaks were provided to all families with disabled children who need them. It also provides a clear case for sustainable funding for the effective delivery of short breaks services. Finally, it concludes that failure to support these families in the long term would result in substantial additional costs to the State.

Through independent analysis of data, nef consulting calculated that the government could make an estimated annual saving of £174 million if short breaks were effectively delivered to all those eligible to receive them. This saving has been based on both the decreased cost of longterm residential care from reductions in the number of disabled children placed outside the family home (£135 million) and the decreased cost to health services from reduction in parents', families' and carers' stress (£18 million).

While based on data in England, the above findings also highlight how similar investments and savings in effectively delivery of short breaks could be made in Northern Ireland.

4. Designing public services fit for the future

4.1 In such a tight fiscal environment we must urgently transform commissioning to incentives long term impact so that less funding does not mean less innovation

4.2 Experience at developing and using effective tools that evaluate the services we provide, the voluntary sector has played a significant part in moving inputs (the activities and programmes offered) and outputs (how many people participated) to analysis impact and outcomes for individual families.

4.3 The commissioning process must incorporate some element of Social return on Investment. We want to see an impact framework developed to support those elements which makes the greatest difference. A stable professional relationship based on trust is what makes the difference in delivering successful public services. To help those most in need, intensive, services need to provide personalised family support based on sustained relationships with highly trusted, skilled workers.

4.4 At Action for Children we have developed an holistic approach towards measuring impact; bringing together data were that data was genuinely associated with improved outcomes (e.g. numbers of young people in employment, education or training or numbers sustaining employment two years or more further to intervention) with more qualitative information drawn from internal and independent evaluations and research into our service provision and with feedback fro service users, staff and partners.

4.5 Common strands identified as having the greatest impact were:

- Use of relationship over time, including outreach, to work successfully with the most vulnerable and excluded

- Commitment to both intensive and long-term support where necessary

- Flexibility to provide services to meet need through intensive contacts

- Sound basis in safeguarding principles and procedures

- Commitment to ensuring the achievement of qualitative outcomes over and above success in meeting timescales and other process measures

- Stable staffing within services albeit contracts are often too short-term to guarantee services

4.6 This information was then assembled in a comprehensive Impact report for the organisation and this will now be an annual process. We believe that our experience is worthy of consideration in reviewing performance systems that concentrate on impact and not on efficiency of processes which have served to drive social work attention away from meeting needs of families and to achieving compliance with unhelpful targets.

5. The Nations

5.1 In recognition of block grant funding arrangements, Action for Children's proposals remain constant across the UK. Action for Children's priority is to ensure the allocation of sufficient funds to protect the most vulnerable and neglected children, young people and families in our nations.

[1] Estimate based on Oroyemi, P, Damioli, G, Barnes, M and Crosier, T (2009) Understanding the risks of social exclusion across the life course: families with children, Nat Cen/Cabinet Office; 4%–7% of children are caught up in 'long-term disadvantage

[2] Backing the future: why investing in children is good for us all, New Economics Foundation (nef), Action for Children (2009).

[3] An analysis of Public Expenditure on Children in Northern Ireland (2007), report jointly commissioned by OFMdFM, Department of Finance and Personnel and NICCY. The report highlighted significant disparities in spending which had consequential negative impacts on services for children and young people in Northern Ireland.

[4] Anti-social behaviour intensive family support projects, an evaluation of six projects, Sheffield Hallam University and Salford University, DCLG (2006 )

[5] Counting the Costs, Contact a Family, 2008

[6] Paying in Care: The Cost of Childhood Disability, Dobson and Middleton (1998), Joseph Rowntree Foundation

[7] Child and Family Poverty in Northern Ireland, McLaughlin & Monteith (2006), Equality and Social Need Division, OFMDFM, Belfast

[8] Research undertaken by nef consulting, Part of nef (New Economics Foundation)

CBI - Delivering Public Services in a Time of Austerity

CBI-NI Public Spending Reform Executive Summary

Construction Employers Federation

State of the Construction Industry in Northern Ireland

30 September 2010

Employment

Employment in the construction industry has been decimated in the last two years and half years.

According to the Labour Force Survey the number of people working in construction has fallen from 87,000 in Q4 2007 to 66,000 in Q2 2010. In other words, 21,000 jobs have been lost in only 30 months.

This rate of decline is confirmed in the Quarterly Employment Survey which shows a 27% fall in the number of employees in construction over the same period.

There are currently approximately 13,000 ex-construction workers claiming unemployment benefit.

Current and Future Industry Performance

At Q2 2010 almost half of respondents to the CEF State of Trade Survey (44%) were working at half capacity or less.

According to the Northern Ireland Construction Bulletin, total industry output in Q1 2010 was £695m. This is £179m less than Q2 2007 and equates to a 20% fall.

The outlook for the industry over the next 12 months is bleak. Even though the industry has suffered terribly over the past year an increasing number of companies expect the next 12 months to be worse. According to the State of Trade survey 62% of companies expect a lower workload over the next 12 months.

House Building

The rate of new house building has been cut in half. In 2006 there were 15,300 new house starts. In 2009, only 7,500 new houses were started.

New house completions follow a similar trend, going from a high of 18,300 in 2006 to a low of 9,300 in 2009.

NHBC publishes quarterly figures on new build housing. These figures show that new starts peaked at 3000 in Q2 2005, hit a low of 400 in Q4 2008, and have recovered to 1000 in Q2. There are fears that even this modest recovery is now under threat.

NHBC housing completions have dropped steadily from 2,900 in Q2 2006 to 900 in Q2 2010. There is yet to be any recovery in the rate of housing completions.

NIPSA Comment on HR Connect

Your Ref

Our Ref A/BC/KW

Brian Campfield General Secretary

Mr Shane McAteer

Committee Clerk

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Room 419

Parliament Buildings

Stormont

BELFAST

BT4 3XX

18th October 2010

Dear Shane

HR Connect – NIPSA Comment

Further to your e-mail of 14th October 2010, NIPSA welcomes the opportunity to update the Committee for Finance and Personnel of our experience of the adverse impact on the Northern Ireland Civil Service as a consequence of the NICS contractual arrangement with HR Connect.

As we reported when we last submitted evidence to this Committee, and as we communicated to the Permanent Secretary for the DFP earlier this year, this contract is a mistake that is damaging both efficiency and morale across all Departments.

The following submission reinforces this message by drawing upon both our industrial relations experience of the "new" personnel world brought about by HR Connect and also the extensive research of staff views carried out by both NISRA and Millward Brown Ulster in the latter part of 2009.

We are on the record as stating that these findings are a "wake up" call to Management Side to go back to the drawing board on the provision of future personnel services to the NICS. We repeat our call that what is needed is an accurate, modern payroll system delivered at an appropriate cost with all other functions delivered by a properly resourced, accountable and efficient Personnel Service within the NICS.

Yours sincerely

BRIAN CAMPFIELD

General Secretary

Experience of HR Connect

Introduction

1. In February 2009 NIPSA reported to this Committee that while HR Connect had been launched in 2008 on the basis that "Northern Ireland citizens want and deserve an efficient and effective public service" our experience was that this contract had failed to deliver either efficiency or effectiveness. This remains our view.

The Need to Establish True Cost/'Benefit' of HR Connect

2. At this time, we also emphasised our concern in relation to cost. As the Northern Ireland Audit Office reported in July 2008, the cost of the 15 year HR Connect contract has risen from an original estimate of £328 million to £465 million, with implementation costs alone of £14.7 million. It is not clear, however, since these figures were placed in the public domain, what the full past, current and projected spend has been/will be. We believe these figures should be published.

3. In addition, our major question on cost however, then as now, is that a 'reform' measure, sold on the basis of private sector 'expertise' doing what the public sector could not, has only been capable of delivering any services at all because of NICS investment in shadow arrangements and considerable public sector resources being deployed to "rescue" the Project. In this regard the required breakdown of costs needs to capture: the public sector cost of 'managing' this project; what funds have not been paid to the contractor and what this represents as a testimony to its actual delivery and performance.

4. DFP Officials have claimed previously that they do not know pre-HR Connect, "how good the HR function in the Civil Service was". Benchmark data therefore, did not exist at the point of procurement. Inevitably, therefore, any promise of improvement or even minimal competence (i.e. delivering what has been paid for) from a private sector firm has no comparator/cost with which to compare it. In this way while the Committee may now be presented with improved figures on payroll accuracy, we see no cause for celebration in one basic strand of a contract beginning to meet its targets 3 to 4 years into its operation and only due to consistent rescue from NICS staff. Will this mean that at year 5 or 6 i.e. a third of the way through the contract, the 'old' NICS standard will be reached? We do not believe that anyone would believe that this constitutes 'reform'.

Adverse Impact on Efficiency

5. As previously outlined, the contract's involvement of HR Connect in conducting grievance and disciplinary cases has been a failure. Again, our representatives involved in such personnel cases and, we understand, Departments' retained HR Personnel have found that the "service" is not 'fit for purpose' e.g. HR Connect's minutes of meetings with witnesses continue to have to be rewritten at the insistence of Departmental HR, there is a poor standard of witness statements, recording of interviews, not following due process etc. This has caused numerous difficulties in ensuring that the NICS procedures are followed.

6. It is striking that as late as July 2010, the NICS Corporate HR are engaging in Improvement Workshops at which these same fundamentals of a Personnel 'service' are having to be established (and another 'action plan' generated) due to the fact that NICS Personnel continue to report that employee relations cases are taking longer to conclude than they did prior to HR Connect – particularly in relation to Grievance and Dignity at Work cases.

Deterioration in Industrial Relations Practice

7. As we previously reported the move from an in-house personnel function to a transactional arrangement with the private sector has had negative consequences in terms of industrial relations. The Civil Service industrial relations system was predicated on problem solving by negotiation at the lowest possible level – the 'new' system is built on escalation via lodging of formal grievances on the HR Connect portal. Therein lies both the contradiction and danger of HR Connect in such a context – the need to render its presence and function, however overpriced, indispensible to its client. In addition, the inefficiency of delays as outlined above will inevitably lead to staff (necessarily) invoking their statutory rights as they have no confidence in timely/appropriate redress within the 'new' Personnel system.

8. Another point on industrial relations that needs to be made is that policy should be negotiated, agreed and operational from the point of agreement – not as seems to be the current approach – from the point at which the HR Connect system can "cope" with the outcome of such negotiation. For example, the annual leave allowance is negotiated and agreed as part of a pay deal with the start date for any enhancement stated in a pay agreement. A recent agreement of this kind, however, relating to the 2009 Pay Agreement could not be delivered by HR Connect at the point of agreement between Management and NIPSA. This fails to recognize the fact that an industrial relations timetable should not be shaped by HR Connect's inability to cope/react.

Staff Reaction to HR Connect

9. We previously reported that Staff confidence has been damaged by widespread concern about, inter alia, whether their new HR Connect service will pay them, retain accurate information on them or preserve their right as employees to confidentiality and that these fears are compounded by a system of "Customer Service" system which is wholly inadequate. Given that DFP Officials previously reported to the Committee in February 2009 that "measuring" customer satisfaction is "a key performance indicator", it is clear that the HR Contract has failed.

10. As evidence for this statement, NIPSA would ask the Committee to examine the NICS Staff Attitude Survey of Autumn 2009 carried out by the Human Resource Consultancy Services (HRCS) branch of NISRA. This included questions, inter alia, on Human Resource Services provided by their employer.

11. When asked "Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statement: "Overall, I am satisfied with HR Connect", only 16% of NICS Staff agreed with this statement. This contrasts with figures for satisfaction with Departmental Personnel Branch (61%) and Corporate HR (40%).

12. In addition when asked to agree with the statement "I am confident that HR Connect are knowledgeable enough to answer my queries", the overall figure for the NICS was 15%. Similarly the statement: "HR Connect provide timely responses to queries" only generated agreement from 16% of NICS Staff, while only 17% agreed with the statement - "I am satisfied with the quality of response received in relation to personnel queries". Finally in relation to a statement that "Personnel queries are handled professionally by HR Connect" only 21% of NICS staff believed this to be the case.

Further Staff Reaction - 2009 Millward Brown Ulster (MBU) Research Findings

13. In terms of other research to confirm NIPSA's view, in 2009 Millward Brown Ulster conducted research (using focus groups, in-depth interviews and a telephone survey) that investigated "NICS staff awareness, attitudes and experience of the reform programme to date".

14. The results mirror the hostility towards HR Connect that was expressed in the Staff Attitude Survey. For example the findings revealed:

- Some Departments could not cite any advantages of the HRC System within the group discussions.

- Only 23% had a positive experience of HR Connect (lower than the previous year's figure of 28%). Overall this particular reform caused staff a great deal of stress and frustration. Staff described it as "a disaster."

- There was a general lack of confidence in system.

- The system was described as faceless and "don't really care" in attitude.

- There was also a feeling in many cases that it went live too early, and that this had contributed to many of the "teething problems".

15. In relation to this last finding, NIPSA is aware, however, that the reason the NICS "went early" on some "releases" was due to the fact that the NICS would have incurred costs had they not done so. This is another example of the tail wagging the dog - with the NICS so dependent on its client that the latter dictates the timetable for delivery, even if what is being delivered is inadequate.

16. It is possible that an initial reluctance, from the Management Side, to release this research information was due to embarrassment. For example, within DETI, the desperation to find one 'positive' (as opposed to the 21 negatives reported) on HR Connect unearthed the 'positive' that "Some of the helpdesk staff are "quite pleasant" and respondents said they almost felt 'sorry for them' ".

17. These research findings confirm what NIPSA has been saying about this contract since its inception – it is not 'fit for purpose'. Indeed it is ironic that a memo from the Head of the Civil Service to the new Head of the Shared Service Centre (November 2009), listing a series of issues that need to be addressed, reflected our earlier critique of HR Connect – a critique that Senior Officials from the DFP were treating, at that time, as descriptive of "teething problems".

System Inflexibility

18. NIPSA can offer 3 recent examples of what should be straightforward Personnel responses to events on the ground that demonstrate HR Connect's failure to react either in time, appropriately or at all.

Third Party Access

We have been trying since early 2009 to establish how we would represent our members' interests, at an individual level, in the context of HR Connect carrying out a personnel 'service'. Throughout this process we have witnessed a complete failure from HR Connect, since 2009, to devise a 'system' or way within their processes to facilitate this third party access.

In terms of the timeline on this, it seems incredible that our final negotiations with CHR could be completed in a 10 week period between February and April 2010, conclude in agreement and yet NICS policies can remain stalled and unpublished even after this matter has been brought to the Permanent Secretary's attention. This issue, a relatively straightforward matter, is now scheduled for 'delivery' by March 2011. This appears to be because Corporate HR cannot control its client's timetable for delivery. In our view, this inefficiency is emblematic of the HR Connect 'experiment' in which progress is only possible by devising ways of "working around" the defects of the privatised 'service'.

It is our experience that HR Connect are always on the brink of delivery, with requests for action met with bogus reassurance about them being awarded "higher" and "highest" priority. In reality, nothing happens quickly other than yet another work-around is cobbled together.

ECJ Judgement (Stringer)

In 2009 an ECJ Judgement [Stringer] clarified the rights of employees to accrue annual leave while on long term sick absence. Despite constant reminders from both Trade Union Side and, as we understand it, Corporate HR (CHR), HR Connect has been incapable of adapting their system(s) to cope with such a change. We understand the latest intention, following further intervention from CHR is to come up with an interim solution. Again a modern personnel system that cannot react quickly to a 'change' of this nature is not 'fit for purpose'.

Management Information

It might have been presumed that one of the selling points of an e-HR system would be the swiftness of its ability to retrieve information. This is far from the case. A query we first raised in 2009 – of how long cases were taking broken down by the type of case (Grievance, Discipline etc) has still not been answered despite the NICS "pressing" the contractor (their client) for an answer in March 2010. Similarly when we asked for data on the numbers who were taking partial retirement, we were informed we could get this information but that it was only feasible as a manual exercise given the way information was stored on HR Connect. In response we are informed by Management that "there were problems...in extracting segmented data on employee relation cases" but that a review has been carried out. In other words another gap in what the contractor can provide has been revealed, another NICS rescue plan is draw up. Once again a basic requirement of a modern personnel service, the swift provision of information, can not be delivered, to be followed by the work-around, improvement workshop, plans b, c, d, etc.

Conclusion

19. NIPSA believes that the costly, inefficient, inflexible, cumbersome and unpopular 'reform' that HR Connect represents now requires further scrutiny and a fundamental reappraisal. NICS staff and all other tax payers deserve better than the continued facilitation of this inefficient privatisation.

Advice NI Press Release

News Release 20th October 2010

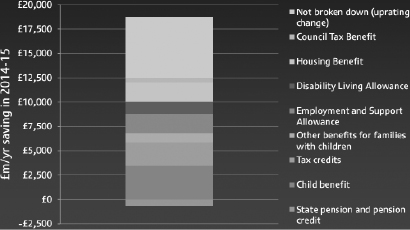

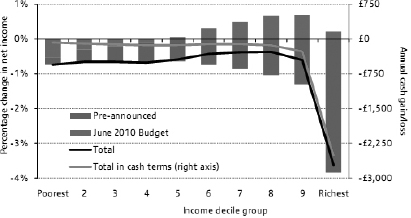

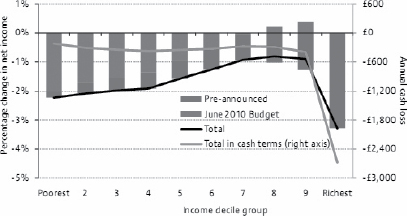

People on welfare benefits bear brunt of Osborne Spending Review

Advice NI, the independent advice network, warned that cuts contained within the Spending Review would impact most on benefit recipients and low income households.

Advice NI drew attention to the proposals to introduce a one year limit to entitlement to contributory Employment and Support Allowance for those in the work related activity group and the freeze to the basic and 30 hour elements of working tax credit.

Advice NI Chief Executive Bob Stronge said:

"The impact of the cuts imposed under the Spending Review particularly in respect of welfare represent an attack on the poorest families. We are particularly concerned about the proposals to time-limit contributory Employment and Support Allowance. Effectively this represents a fundamental shift and reduction in support for people who are no longer able to work because of long term health conditions. Many people affected by this change will feel that they have paid their tax and National Insurance contributions and yet they will be denied support when they need it most."

Advice NI also drew attention to the raft of other cuts that will affect welfare recipients including the cut to the Support for Mortgage Interest (SMI) scheme; the proposal to limit SMI to 2 years for new Jobseeker's Allowance claimants; proposals to cap Housing Benefit (HB) and reduce HB awards to 90% of the initial award after 12 months for claimants receiving Jobseeker's Allowance; proposals to introduce a more stringent test for Disability Living Allowance claimants; the reduced up rating formula for working out benefit increases each year; and the freeze to child benefit.

Mr Stronge continued:

"We are gravely concerned that Government has viewed the welfare budget as an easy target to cut. We have no doubt that the poorest households are being hit hardest."

"In the current economic crisis many lower income families in Northern Ireland are struggling to pay bills and make ends meet. Advisers are already preparing themselves to cope with increased demands on advice services due to worsening levels of debt; fuel poverty issues over the winter months; people facing redundancy situations and a whole range of other issues at this difficult time. We would urge those in positions of authority and influence to continue to support the work of the advice sector."

Over the last year, Advice NI centres dealt with over 227,000 enquiries across Northern Ireland, the majority of which were social security and debt related. This was in the context of Northern Ireland coping with recession, increased redundancies, mortgage repossession actions and increased numbers of people turning to the social security system.

If you are worried about how Spending Review might affect you, or you would like to speak to an adviser please contact Advice NI for help.

End Notes:

1. Bob Stronge (Chief Executive) can be contacted for further information. Advice NI, 1 Rushfield Avenue, Belfast BT7 3FP

Tel: (028) 9064 5919 or Mob: 07789756954

Advice NI is the umbrella body for the independent advice network in Northern Ireland Advice NI membership currently stands at 70 organisations from across Northern Ireland

2. Advice NI members deal with over 227, 000 enquiries per year, with the majority being social security benefits related

3. If you would like to find out more about the work of independent advice agencies in your area or you would like to obtain copies of the various publications produced by Advice NI, please contact Advice NI, 1 Rushfield Avenue, Belfast; Telephone (028) 90 645919; E-mail info@adviceni.net; Website www.adviceni.net.

NICVA Briefing Paper

Smart Solutions in tough times.

Briefing for members of the Finance and Personnel Committee

1. NICVA, the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action, is a membership and representative umbrella body for the voluntary and community sector in Northern Ireland. Our membership reflects the make up of the sector in terms of both thematic (issue based) and geographical representation. NICVA offers a range of services including advice (governance and charity advice, HR), fundraising, research, policy and lobbying, training and consultancy.

2. In July 2010 NICVA commissioned a paper from Oxford Economics on the likely impact of public expenditure cuts in Northern Ireland. They estimated then that the NI Executive will be expected to make savings of at least £2billion. The outworking of the Spending Review and settlement figure for Northern Ireland confirmed our worst fears.

2.1 As budget holders struggle to meet these demands NICVA is concerned that voluntary and community organisations delivering public services will be vulnerable to unfair and potentially disproportionate cuts. This is because voluntary and community sector providers are often seen as additional to statutory services – even if they have been contracted to provide the core services of a department.

2.2 The reduction in public expenditure could pose a real threat to the capacity and capability of significant parts of the sector. The sector is realistic and is not adopting a begging bowl approach or seeking immunity from the financial pain. It is simply trying to ensure that it is not treated unfairly by accident rather than design.

2.3 NICVA believes that voluntary and community organisations offer a smart solution to the tough economic decisions that lie ahead. In most cases the services delivered by voluntary and community organisations are effective, efficient and provide real value for money. The consequences of unfair and disproportionate cuts are likely to impact on the most vulnerable people in our society. We are calling on government to agree its priorities and the outcomes it wants to achieve for Northern Ireland. And then work with the voluntary and community sector to find smart solutions to the difficult decisions that lie ahead.

3.0 As the programme of cuts rolls out we believe that the large number of budget holders across the system could be tempted to take what they feel may be easier options – cut the external or peripheral, as something that can no longer be afforded. If this turns out to be the case we are concerned that voluntary and community sector organisations will feature disproportionately highly as the easy option. We are asking members Committees of the Northern Ireland Assembly to ensure departments give full consideration to the outcomes they are trying to achieve with the budget it is proposing.

3.1 From NICVA's point of view it is critically important to know the following:

- If a service is to be cut we need to ask how the decision was made. What evidence was considered?

- What are the opportunity costs of the decision? Will it end up costing more in the medium and long term?

- How many people will be affected?

- Do the people likely to be affected come from a vulnerable group or community such as older people, people with a disability, children or a disadvantaged/deprived area? Will they be disproportionately affected?

- Will the service continue to be provided 'in-house'? If so is there a business case to support this as the most effective and efficient method of delivery?

- Has an objective decision been made in order of priority based on outcomes and value for money?

- When it comes to bids for new functions, do the activities planned merit greater priority and are they a more beneficial use of resources than those activities they propose to cut?

4. As the Department for Finance and Personnel has over all responsibility for setting the standard for the effective and efficient use of public money the findings of The NI Audit Officer (NIAO) report into the voluntary and community sector "Creating Effective Partnerships between Government and the voluntary and community sector" will be of interest to Finance and Personnel Committee Members. The report, published in September 2010, found that voluntary and community organisations made a significant contribution to the aims and objectives of government. However when it comes to funding for voluntary and community organisations the NIAO warned that "public sector bodies must be aware of the potential effects of their procurement arrangements on the Sector, and guard against any unintentional and unwelcome alteration to voluntary and community organisations' roles."

4.1 The Audit Office went on to say that "Funders should also ensure, through regular monitoring and reporting, that they adhere to the best practice guidance. In our view there needs to be a greater focus on:

- avoiding unnecessary bureaucracy, in all aspects of the funding mechanism (which can increase costs for both funders and funded bodies) – in applications and renewals; timeliness of payments; and monitoring and audit.

In this respect we will work with the Department and others to establish and promote practical guidance for monitoring and auditing Sector organisations;

- better communication – through improved liaison and contact between public sector funders and voluntary and community sector organisations. In particular, greater clarity about the funders' monitoring and reporting requirements; and greater sharing of information and assessments of organisations between public sector funders; and

- outcomes - the work being done to develop, for example, 'Social Return on Investment' measures should assist in this.

For more information contact Lisa McElherron, Head of Public Affairs, NICVA, 02890 877 777, 0778 5278928, lisa.mcelherron@nicva.org

Advice NI response to White Paper

News Release 11th November 2010

'Universal benefit being paid for by savage cuts to the social security system' warns

Advice NI

Advice NI, the independent advice network, today warned that the Coalition Government's latest welfare reform proposals within their White Paper is being paid for by almost £20 billion cuts to the social security benefit system.

The White Paper sets out plans to overhaul the benefit system and provide greater incentives for work and sanctions for those unwilling to do so.

Speaking about the White Paper, Advice NI Chief Executive Bob Stronge said:

"The proposals are being paid for by extensive cuts to the current benefits system including harsher tests in respect of disability benefits; cuts to mortgage support and housing benefit; and reduced up rating formula for working out benefit increases each year. Benefit claimants survive on the lowest levels of income and advisers are already dealing with people who have seen their benefits reduced and who simply do not know how they will cope."

The White Paper has been put together by Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith and key proposals include a single universal credit which replaces work-related benefits. Claimants moving into work will keep more of their income than now, but face losing benefits if they refuse a job.

Bob Stronge continued:

"We know that there are already stringent conditions for job seeking claimants in terms of being available for and actively seeking work. We would question whether even more draconian measures are necessary, particularly in a climate where there are very few employment opportunities. We also know that many people including the long term unemployed, people with health problems and people with childcare and caring responsibilities face significant barriers to employment will require support to move from welfare to work. There must be a focus on the needs of benefit recipients as they make their journey from welfare to work."

Advice NI has urged anyone who has been affected by recent welfare cuts or who are concerned about how they might be affected to seek help from an Advice NI adviser.

End

Notes:

1. Bob Stronge (Chief Executive) can be contacted for further information. Advice NI, 1 Rushfield Avenue, Belfast BT7 3FP

Tel: (028) 9064 5919 or Mob: 07789756954

2. Or contact Kevin Higgins (Head of Policy) Advice NI, 1 Rushfield Avenue, Belfast BT7 3FP

Tel: (028) 9064 5919 or Mob: 07743496957

3. Advice NI is the umbrella body for the independent advice network in Northern Ireland

4. Membership: Advice NI membership currently stands at 70 organisations from across Northern Ireland

5. Advice NI members deal with over 227, 000 enquiries per year, with the majority being social security benefits related and debt

6. If you would like to find out more visit Website www.adviceni.net.

Colm McCarthy - Centreforum Revised

CentreForum Conference, London, November 12th 2009

Ireland's Second Fiscal Consolidation – Lessons from the Last Time[1]

Colm McCarthy,

School of Economics,

University College Dublin.

colm.mccarthy@ucd.ie

1. Second Time Round for Ireland…….

For the second time in a generation, Ireland is in a deep fiscal crisis, with double-digit borrowing, escalating debt and concerns about the country's solvency in international debt markets, reflected in the second largest adverse bond spreads of any Eurozone member. What's different this time is that the fiscal system's second crisis since the foundation of the state has coincided with the banking system's first. The banks have lost a large portion (on worst estimates, all) of their capital and survive on liquidity furnished, on a prodigious scale, by the European Central Bank.[2]

Parallels with the first Irish fiscal crisis in the 1980s are of limited value given the quite different circumstances. The 1987 to 1990 consolidation did not coincide with a banking collapse, nor did it coincide with a worldwide credit crunch and a rapid world trade contraction. The next section argues that fiscal consolidation post-1987 was less daunting than is likely to be the case over the next few years, and that the role of current expenditure cuts has been exaggerated in journalistic renderings of the history of the period.

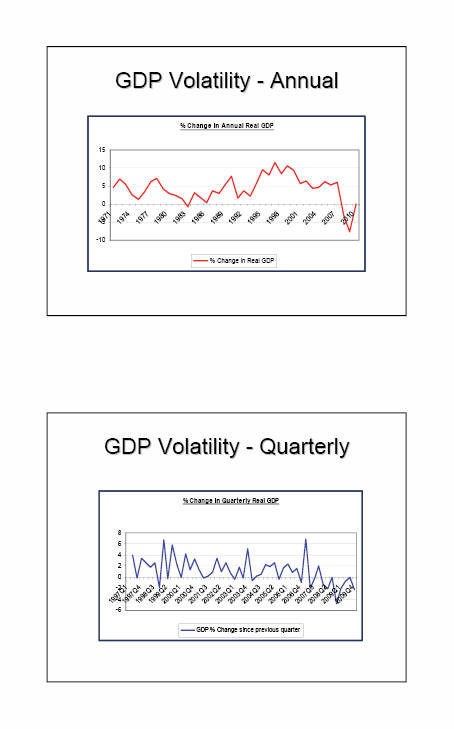

The recent deterioration in the Irish public finances has been extraordinarily rapid – even with substantial tax rate increases, revenue has fallen far more rapidly than the tax base, while spending has continued to advance, despite the widespread perception of cutbacks. The conduct of fiscal policy since 2000 is reviewed in section three, and the prospects for a medium-term fiscal consolidation in section four. The paper concludes with some lessons from Irish experience for politicians - and for economists.

2. The 1980s Fiscal Correction and the first Bord Snip[3]

The current fiscal crisis is Ireland's second, and it is understandable that commentators should seek parallels with the first. By 1978, the debt ratio (Exchequer debt to GNP) had reached about 65%[4] and economists had begun warning about sustainability. In January 1980, Taoiseach Charles Haughey made a famous TV broadcast in which he opined that '…we are living beyond our means'. He went on to promise an immediate fiscal austerity programme, but relented quickly. The subsequent development of Exchequer borrowing is shown in the chart.

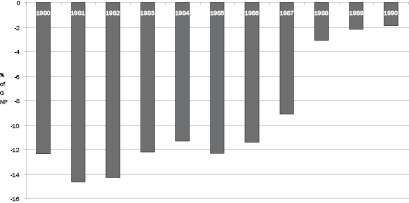

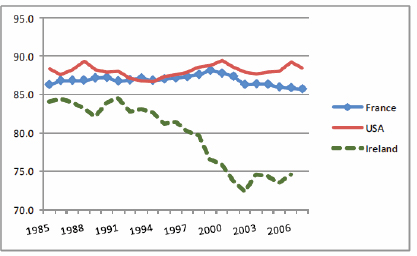

Chart 1: Exchequer Borrowing as a % of GNP in the 1980s

Borrowing ran at double-digit rates for over a decade from the mid seventies, and by 1988, when sustainability was re-attained, the debt/GNP ratio had reached 117%. It is worth remembering that various fiscal programmes were prepared in the early 1980s which envisaged better macro performance than actually occurred and a more rapid return to fiscal balance. What happened in 1988 was planned to happen by 1983 or 1984.

The large deficits from 1980 onwards arose principally from a combination of revenue weakness (despite sharp increases in tax rates), expenditure growth in the early years and the build-up of debt-service costs. There were three general elections in the 1981-82 period, each of which saw a change of government and it is interesting to focus on the position in 1987 compared to 1982 under the main expenditure and revenue headings. This spans the period in office of the only long-lived government (the Fine Gael-Labour coalition took office in December 1982) during the fiscal crisis after the penny dropped, so to speak. The figures are:

Table 1: Fiscal Policy over the 1982-1987 Period.

| Cumulative % Change | Average Annual | |

| Current Services | 40.6 | 7.1 |

| Central Fund | 71.6 | 11.4 |

| Total Current | 47.3 | 8.1 |

| Exchequer Capital | -17.9 | -3.9 |

| Total Govt Spending | 36.5 | 6.4 |

| Total Revenue | 48.7 | 8.3 |

| Nominal GNP | 46.3 | 7.9 |

| CPI | 35.4 | 6.3 |

Source: Department of Finance, Budgetary and Economic Statistics 2009.

Current non-interest spending rose only a little in real terms, but Central Fund (mainly debt service) rose dramatically. Exchequer capital spending actually fell, so total government spending barely exceeded CPI inflation. The lesson is that, if the tax base is growing only very slowly, as evidenced by sluggish nominal GNP[5], the build-up of debt service means that spending must actually be cut – it is not enough to just hold the line. The primary surplus never rises fast enough. The consequence was a fiscal crisis that lasted eight years from Mr. Haughey's dramatic TV broadcast, and a decade from the realization, at least in the economics profession, that this was indeed a fiscal crisis. Debt service absorbed about 30% of tax revenue for ten straight years, total employment in 1991 had barely regained the level of a decade earlier and there was net outward migration in each year bar one from 1980 to 1991. In total, 221,000 emigrated over this period, out of a population averaging about 3.5 million versus 4.5 million at April 2009. All of this was accompanied by external imbalance and successive devaluations within the European pegged exchange rate system of the time. Honohan and Walsh (2002) provide an extended discussion of the attempts to restore fiscal balance during these years.

A minority Fianna Fail government led by Mr. Haughey and with Ray McSharry as Minister for Finance took over in March 1987, and proceeded to establish the first Bord Snip in May 1987. It was led by the secretary of the Department of Finance, Sean Cromien, who has recently penned an account of the episode as viewed from the civil service (Cromien (2009)). A surprising number of myths, none of them the handiwork of the participants, has grown up about the activities and impact of this body, of which the author was a member.

Briefly, there was no significant reduction in the real volume of current spending as a result of Bord Snip 1. There was a further squeeze on capital spending, a mistake in retrospect, but most of the adjustment came on the revenue side. The 'slash and burn' stories about 1987, references to the Finance minister as Mac the Knife, decimation of public services and so forth are just journalistic invention. It never happened and the actual numbers are in the next table.

Table 2: The First Irish Fiscal Correction 1987 to 1990

| 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | |

| Gross Current Expenditure | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 8.5 |

| Exchequer Capital | -9.2 | -23.7 | -3.0 | 13.1 |

| Total Government Expenditure | 2.7 | -1.3 | 0.5 | 7.0 |

| CPI | 3.1 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 3.3 |

| Gross Exchequer Current Revenue | 8.2 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 8.9 |

| Exchequer Deficit % GNP | -9.1 | -3.1 | -2.2 | -1.9 |

Debt service costs changed little over these years (interest rates had fallen, offsetting the rising debt volume), so the figures for total current spending and for non-interest spending (not shown) are similar. Current spending in real terms rose in 1987, fell a little in 1988, fell a little faster in 1989, but rose quite rapidly in 1990 by which point the real volume of current spending, however measured, was comfortably above the 1987 level. The big contributors to the adjustment were the severe cuts in capital spending and the sharp improvement in revenue. Real GNP through the 1980s developed as follows.

Table 3: Real GNP Growth in the 1980s

| 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 |

| 2.6 | 1.8 | -1.3 | -1.9 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 6.5 |

In 1986, the volume of GNP was about the same as it had been in 1980. It then grew 17.6% to 1990, an annual average real growth rate of 4.1%. A contributory factor was a well-executed devaluation in August 1986. The tax amnesty introduced in the January 1988 budget also contributed, yielding at least 2% of GNP more than expected. It was one of the most successful tax amnesties anywhere at the time, and attracted attention from policymakers internationally (Uchitelle (1989)).

The first Bord Snip contributed no doubt, but more in the sense of the old football adage that '….you make your own luck', in other words, you get yourself into a position to get lucky. The capital cuts, in retrospect, were overdone during the 1980s, tax rates were raised to self-defeating levels and the emerging fiscal crisis could, and should, have been addressed much earlier. If it had been acknowledged in say 1978 and dealt with decisively, it could have been over by about 1982 or 1983.

By the end of the 1980s, the public did not need persuading that there was indeed a fiscal crisis: the topic had dominated political debate for a decade. The current position is decidedly less favourable in that regard: the deterioration has been sudden, and has coincided both with a domestically-generated banking collapse and a deep international recession. Public acceptance of the need for severe spending adjustments has been weakened by a decidedly populist public spending competition through the bubble period between government and opposition, which lingers in the form of escapist proposals to somehow avoid fiscal adjustment. A further difference from 1987 is the markedly less forgiving condition of the international sovereign debt markets, in which Ireland was one of the few heavy borrowers at times during the 1980s.

On the plus side, the extraordinary pace of spending increases in the last decade means that Bord Snip 2 has been operating in what the US Air Force would describe as a target-rich environment, which was not the case in 1987.

3. Fiscal Policy since 2000

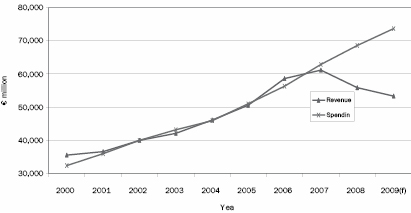

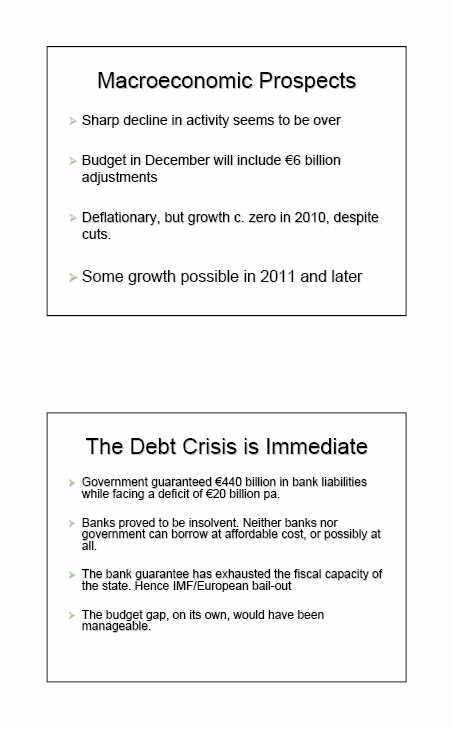

From a position of fiscal balance and a declining debt ratio that had lasted over a decade, the public finance position has this year lurched into heavy deficit, and the debt ratio has begun to rise rapidly. On the GGB definition, gross debt will have more than doubled as % GDP in just two years by end 2009. The table shows developments in some public finance aggregates since the turn of the century.

Table 4: Trends in Spending, Deficit and Debt, 2000 to 2009.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009f | |

| Tot Spend % Chg* | 10.4 | 16.1 | 11.0 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 7.1 |

| Current - CF % Chg | 11.4 | 19.7 | 14.8 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 12.1 | 9.9 | 6.0 |

| CPI % Chg | 5.6 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 4.1 | -4.4 |

| Total as % GNP | 34.7 | 36.7 | 37.5 | 36.6 | 36.2 | 37.0 | 36.8 | 38.8 | 44.5 | 51.1 |

| GGB Deficit** | 4.7 | 0.9 | -0.4 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 0.2 | -7.3 | -12.0 |

| GGB Debt** | 37.8 | 35.6 | 32.2 | 31.0 | 29.4 | 27.5 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 44.2 | 59.0 |

*Total = gross current + Exchequer capital + Central Fund (CF).

** Both as % GDP

The recent sharp deterioration in both deficit and debt ratios is of course driven in part by the unprecedented decline in GDP. On any measure, spending grew rapidly from 2000 onwards, the more so when some of the measured output growth was borrowed from the future so to speak, through building a large unsold stock of houses, retail and office space, which will overhang the market for years. Government spending relative to GNP was growing up to 2007, and even more so if the GNP growth rates and hence tax buoyancy from say 2002 onwards were in truth not as good as they looked. The dramatic increase in spending ratios in the last couple of years has a large cyclical component, but it is salutary to note that the real increase in current spending in 2009, even excluding debt service, will likely be in double digits.

This continuing expenditure growth has of course been accompanied by an unprecedented collapse in tax revenue. This has exceeded by a large margin the decline in the tax base, reflecting the excessive reliance on taxing transactions in assets. Receipts from stamp duty, VAT on new house sales and CGT on non-residential property fell by 4 full GNP points from 2006 to 2009.

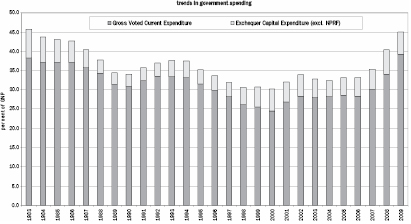

Chart 2: Exchequer Spending, excl Debt Service, as % GNP, since 1983

The recent economic history of Ireland can be divided provisionally into the fiscal consolidation phase up to the currency crisis of late 1992 and early1993; the Celtic Tiger period which lasted until about 2001; followed by the Bubble, which began to burst in mid-2007. The Irish Bubble has been, in relative terms, one of the largest in a developed country and seems destined to spawn a cottage industry for economic analysts to rival that created by the Tiger. The main domestic components were failures in expenditure control and in the regulation and supervision of the banking system. Of course even if Irish policy had been flawless in both of these dimensions, the economy would now be experiencing a serious downturn, but it is a form of denial, and not conducive to the best policy response, to pretend that the current crisis was caused by an asteroid strike, or the unfortunate Brothers Lehman. Ireland has had a pretty spectacular public spending bubble, concealed from view by the transient tax revenues generated by a credit-fuelled property bubble. Spending grew dramatically, but the public finances stayed in balance until 2007. The rocketing deficit in 2008 and 2009 reflects the simultaneous bursting of the double-Bubble, coinciding of course with the international downturn and some more local difficulties, including sterling weakness: the United Kingdom remains a key market for Irish exports, and Ireland has more non-Euro trade than any other Eurozone member.

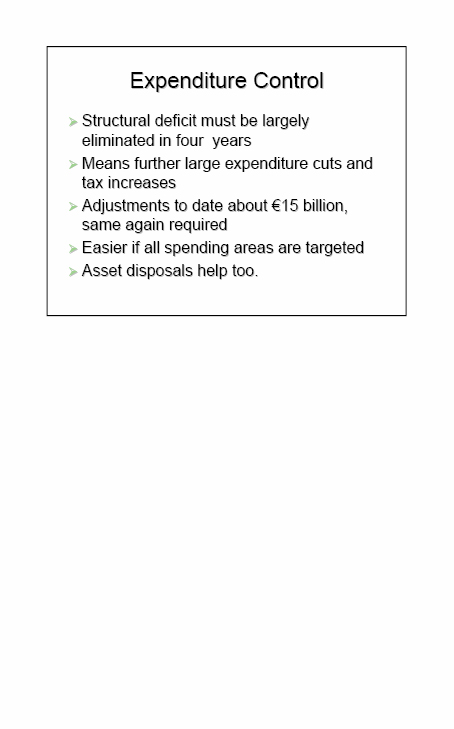

4. Fiscal Consolidation over the Medium Term

The recent revised programme for government reiterates the commitment to the fiscal consolidation targets outlined at the time of the supplementary budget last April. These are

Table 5: Government's Fiscal Consolidation Programme

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| GGB Deficit % GDP | 12.00 | 10.75 | 8.50 | 5.50 | 3.00 |

| GGB Debt % GDP | 59 | 73 | 78 | 79 | 77 |

| Assumed GDP Growth | -7.7 | -2.9 | +2.7 | +4.2 | +4.0 |

In April, the GGB deficit for this year was expected to be 10.75% of GDP. Due mainly to tax revenue weakness, this now looks unlikely, and 12% is more realistic. The GGB debt, shown at 59% in the April document, will presumably be several points higher, as would the figures for subsequent years. The GDP decline shown for 2010 is pessimistic compared to more recent forecasts, but the numbers pencilled in for 2011, 2012 and 2013 are ones a lot of people would settle for. The adjustment, crucially, is expected to come substantially on the revenue side. Tax revenue is assumed to rise 27% from a 2009 base now unlikely to be reached. The figures also assume that spending grows very little, despite the inevitable build-up of debt service costs, implying significant real cuts in the non-interest component. These are forecasts, and debating their plausibility is pointless. What matters is the target deficit for 2013, at the SGP limit of 3%. The Stability and Growth Pact has been relaxed but not abandoned, and Eurozone members are still expected, when the dust settles, to (i) not breach the 3% limit, but also to (ii) adhere to the 0% average over the cycle.

The revised government programme agreed between Fianna Fail and their Green coalition partners early in October states, regarding the re-affirmation of the fiscal consolidation programme,

'This plan has been welcomed by the European Commission'.

No doubt it has, but more importantly it has been permitted by the European Commission, and as a concession – no other member state, so far as I am aware, has been given until 2013 to get back to 3% borrowing. Thus those, such as the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, who argue for a much longer period of adjustment are in effect arguing that Ireland should go back to the Commission and re-negotiate the terms of its adherence to Eurozone rules. There can be no presumption that such a re-negotiation would succeed.

Nor is it self-evidently in Ireland's interests to spin out the adjustment to 2017 or 2018, were it to be permitted by the Commission, and by the international sovereign lenders. The exit debt ratio could easily exceed 100% of GDP at the end of a decade-long adjustment.[6] An important difference between the current situation and the 1980s is that worldwide sovereign debt issuance is at unprecedented levels and the markets, though improving, remain stretched. As quantitative easing programmes are withdrawn, the bond issuance which they have been supporting will also have to be trimmed, so the European Central Bank's stance will affect Ireland's options. Finally Ireland's credit spread at ten years against the bund has recently been around 150 basis points, the largest adverse spread of any Eurozone member. Bluntly, this means that the markets are not convinced that Irish debt is free of risk, and countries with higher debt ratios than Ireland, and no greater liquidity, enjoy narrower spreads. Any move to delay the fiscal adjustment could see spreads widen further, adding quickly to debt-service costs and thus offsetting at least in part the intended relaxation of fiscal policy. Some of those advocating stimulus or a slower adjustment are assuming an elastic supply of sovereign credit at unchanged cost, as well as low fiscal leakages, neither of which is self-evidently realistic.

Fiscal consolidation must be seen in the broader policy context. In addition to fixing the budget, Ireland needs to fix the banking system, cut wage and non-wage costs to restore competitiveness and de-leverage the national balance sheet. In a recent address to a conference in Dublin , the Central Bank Governor suggested that a reasonable medium-term target would be to re-balance the economy with revenue and expenditure shares in GNP around the levels prevailing eight or ten years ago (Honohan (2009b)). This would mean a sharp increase in the ratio of tax revenue to GNP from current very depressed levels. Rates of tax have already been increased and there may be further increases on the way, but the tax/GNP ratio should rise anyway without rate increases. People will have to replace cars eventually, for example, and the rise in the savings ratio, which has been depressing VAT and excise yields, cannot go on forever.

But the Governor's suggestion also implies that the recent sharp increase in the ratio of public spending to GNP should be reversed. Some of it is cyclical and will reverse anyway as the economy recovers, but it must be accepted that some of the increases during the Bubble were based on a misperception of the economy's long-run taxpaying capacity. What must be avoided is any nostalgia, in any area of policy, for the unbalanced economy which emerged in the final years of the Bubble. In 2007, Ireland had full employment, easy credit and a balanced budget, but also had iffy banks, excess leverage throughout the system, crowding-out of the traded sector and poor competitiveness. It felt fine, but it was not a good place to be.

A re-balanced economy will not look like 2007, unless Ireland somehow manages to persuade foreigners to finance another Bubble. At its simplest, it will need to switch resources from making buildings and other non-tradables to making exports. It is clear from the table that the shrinking of the construction sector continues apace, with employment

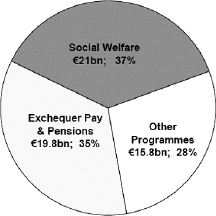

The 1987-90 fiscal consolidation finally took place in a more propitious environment than seems likely over the next four or five years: GNP growth rates will do well to average 4%, the sovereign debt markets are more crowded and less forgiving, and Ireland cannot have another last-chance tax amnesty. Nor of course can it have a currency depreciation. But the years preceding the 1987 corrective action were ones in which current and capital spending had grown very little – this time, the fiscal correction succeeds a bubble in public spending as well as in credit expansion, and the scope for expenditure cuts is substantial.[7] The spending cuts proposed to government must be substantial given the circumstances, and reflect the distribution of current spending. In a modern welfare state, spending control means control of pay and control of social transfers.

Chart 3: Distribution of Current Exchequer Spending in Ireland, 2009.

5. Lessons from the 1980s for Politicians (and Economists)

- The principal lesson for policymakers is that little was achieved by delaying the first Irish fiscal adjustment. Had action been taken from as late as 1980, and it would have been justified even earlier, the economy could have skipped five miserable years.

- A medium-term consolidation is more likely to under-achieve, the rosier the macro projection on which it is based. Better be cautious, and be surprised on the upside!

- Even with rising tax rates, it is difficult to realise substantial increases in tax/GNP ratios in a downturn.

- With debt-service building up, and pressure on social transfers, actual cuts are needed for stabilisation – it is not enough just to halt the rise in real non-interest spending.

There are some lessons for economists too. While the full dimensions of the current Irish implosion were foreseen by no-one, it is simply untrue that no warnings were issued about the emerging banking and fiscal crises: whether they were loud enough is another matter, although what is heard matters more than what is said. The IMF reports on Ireland from the early years of the current decade make interesting reading, especially on banking and credit developments. On the lack of discipline in expenditure control see Lawlor and McCarthy (2003). But it seems obvious that, after the abolition of the currency in 1999, many Irish economists began to focus more on micro-policy concerns, believing that the big macro issues including external financial balance and budgetary policy (given the Stability and Growth Pact rules) had been taken off the list of things likely to go wrong. This was a bad call!

The legendary hurler Christy Ring was noted for taking advantage of the inattention of Cork's opponents when the referee held the ball after stoppages in play. He was accused of gamesmanship, taking quick frees, even of swapping a soggy ball on a wet day for a crisp dry one secreted on his person. Asked about this after he retired, Ring remarked:

'Always keep your eye on the ball, especially when it's out of play'.

Appendix: Choice of Denominator for Fiscal Ratios