Session 2009/2010

Second Report

Committee For The Environment

Inquiry into Climate Change

Volume Two

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

AND WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS RELATING TO THE REPORT

Ordered by the Committee for the Environment to be printed 23 November 2009

Report: NIA 24/09/10R (Committee for the Environment)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

The Committee for the Environment is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 46.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Consider relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquires and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on any matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of the Environment

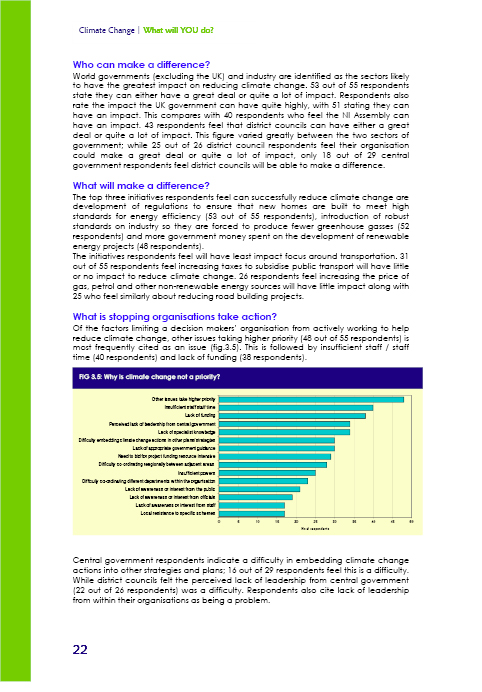

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mrs Dolores Kelly (Chairperson) 6

Mr Cathal Boylan (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr David Ford Mr Adrian McQuillan 7

Mr Ian McCrea Mr Alastair Ross 1

Mr Peter Weir Mr Daithi McKay

Mr John Dallat 5 Mr Danny Kinahan 3,4

Mr Roy Beggs 2

1 From January 21 2008, Mr Alastair Ross replaced Mr Alex Maskey on the

Committee for the Environment.

2 With effect from 15 September 2008 Mr Roy Beggs replaced Mr Sam Gardiner.

3 With effect from 29 September 2008 Mr David McClarty replaced Mr Billy Armstrong

4 With effect from 22 June 2009 Mr Danny Kinahan replaced Mr David McClarty

5 With effect from 29 June 2009 Mr John Dallat replaced Mr Tommy Gallagher

6 With effect from 3 July 2009 Mrs Dolores Kelly replaced Mr Patsy McGlone

7 With effect from 17 September 2009 Mr Adrian McQuillan replaced Mr Trevor Clarke

Table of Contents

Executive summary

Summary of Recommendations

2. Approach and focus of report

3. Current policy position on climate change in Northern Ireland

• Policy development

• Legislation

• Co-ordination of legislation

• Climate / carbon impact assessments

• Northern Ireland Targets

• Sector specific targets

• Role of the Committee on Climate Change

• Role of the MET Office

• Reporting mechanisms

6. Structures and Accountability

• Government structures

• Role of Government

• Role of DOE Climate Change Unit

• Delivery mechanisms including delivery of carbon commitments

• Public procurement

• Role of the Planning System

• Role and responsibilities of Local Government

• Investment and innovation

Cost of delivering climate change obligations

8. Sectoral targets and Action

• Energy

• Transport

• Waste

• Land use

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Other Papers Submitted to the Committee

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 3

Written Submissions

Airtricity

20th February 2009

The Committee Clerk

Environment Committee Office

Room 245

Parliament Buildings

Stormont

BT4 3XX

Dear Mr McGarel

Thank you for the opportunity to contribute to the Northern Ireland Assembly Environment Committee Enquiry into Climate Change. We have attached 2 documents. The first sets out Airtricity’s views on the threats and the opportunities arising from the challenge of climate change. The second attachment sets out what we believe to be the targets Northern Ireland should meet in terms of renewable energy and the barriers that need to be overcome to achieve them.

In either instance, I would be more than happy to give evidence to the committee in person and explain further the content of our presentations.

Yours sincerely

Mark Ennis

Director of Communications & Strategy

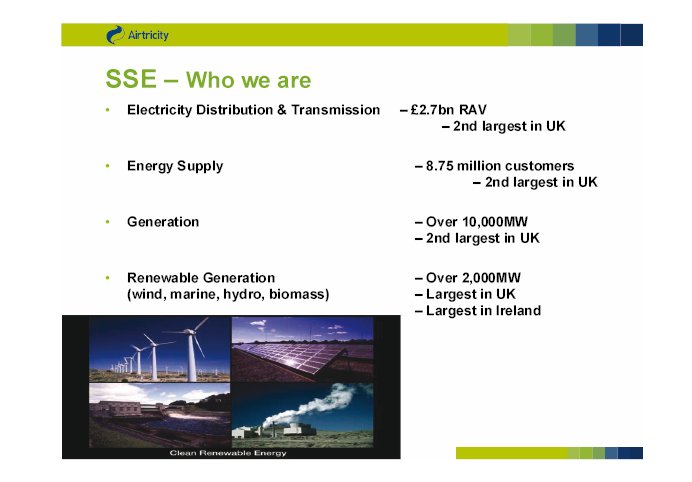

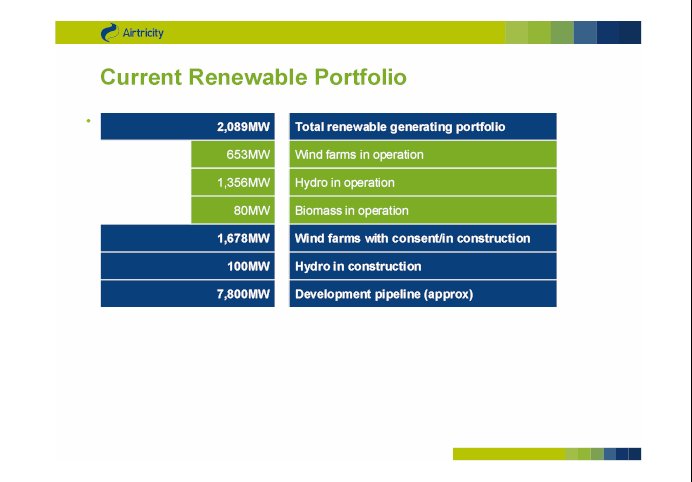

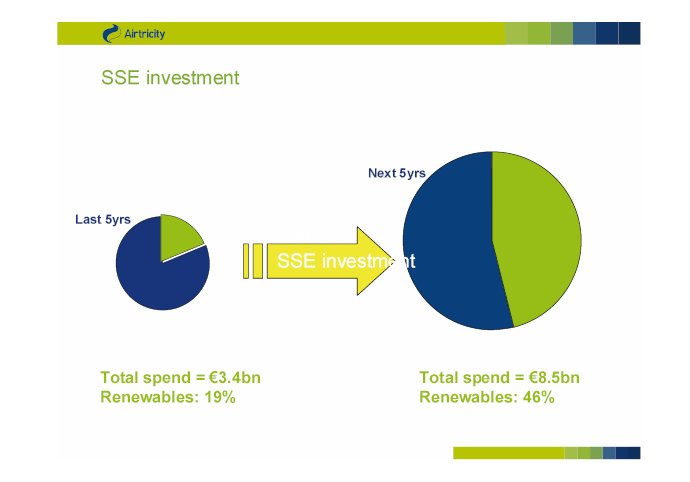

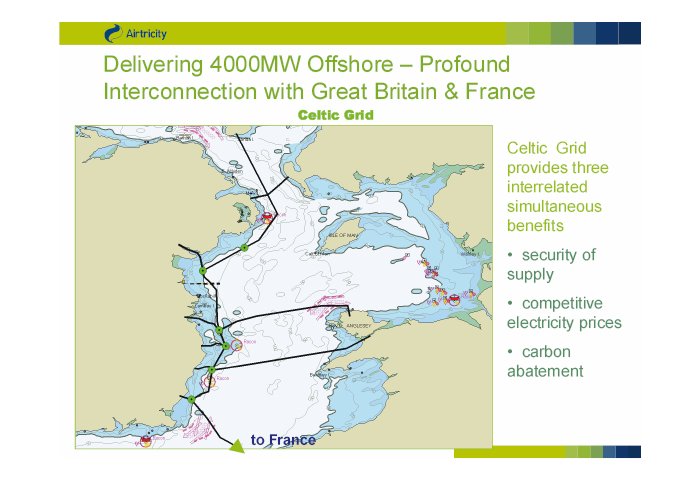

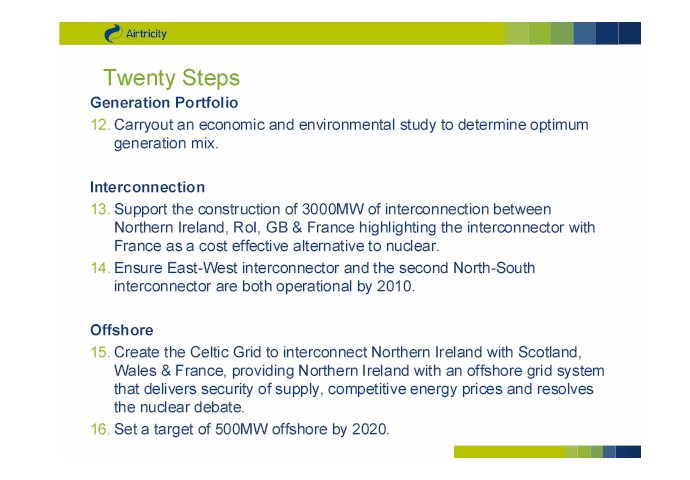

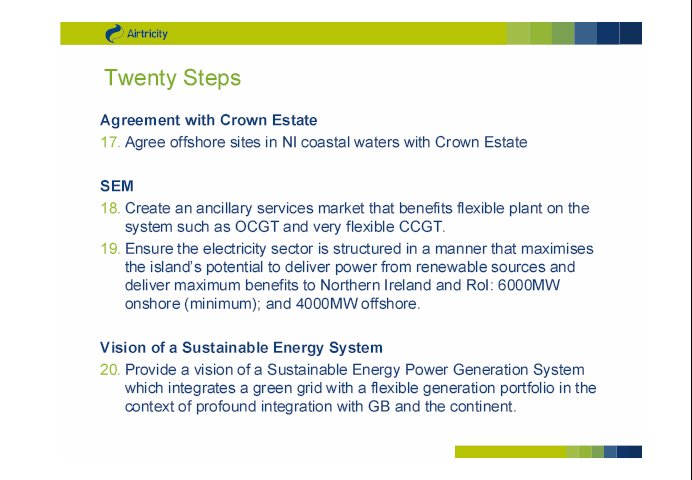

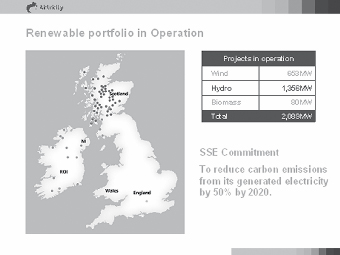

Airtricity is the renewable energy development division of Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE). We are the UK and Irelands second largest utility with over 9 million customers and 10,000 MWs of generation capacity Importantly we are the UK and Irelands leading renewable generator with over 2000MWs of renewable generation (both wind and hydro) in operation and a further 1500MWs in the course of construction. We take climate change and the need to develop a sustainable future seriously. As proof of this we have made a public commitment to reduce the carbon emissions from our electricity generation fleet by 50% by 2020.

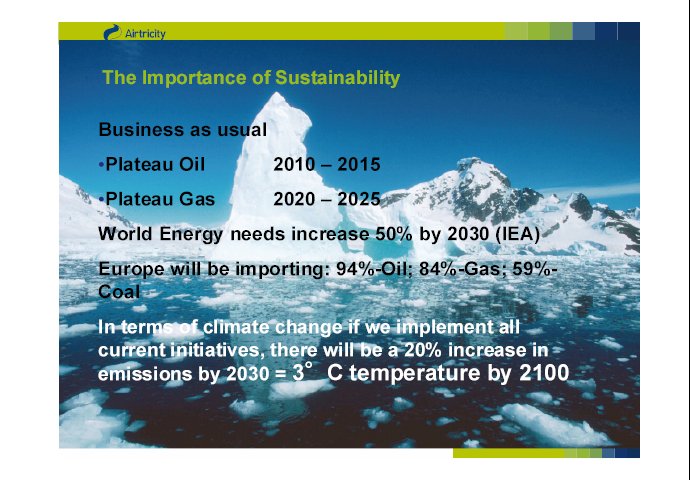

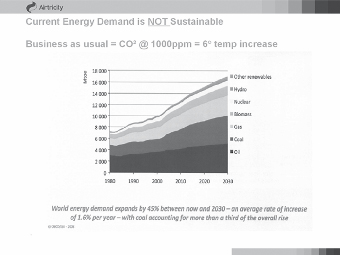

Addressing climate change while at the same time securing our energy supplies represents a huge challenge, and also a huge opportunity for businesses and countries that recognise the issue and are prepared to be part of the solution. Security of energy supply issues are something that all businesses will have to address. Even allowing for the current recession the world energy needs will increase by 45% by 2030 (IEA) While world demand grows Europe’s exposure to fossil fuel shortages will increase Within 20 years Europe will be importing 94% of its oil, 84% of its gas and 59% of its coal. The International Energy Agency has just carried out the most comprehensive study of 700 of the world’s oil fields (the vast majority) and found that they are depleting at a rate of 8% per annum. This means we will have to find the equivalent of 4 Saudi Arabia’s if we are to meet world demand by the middle of the century. The increasing exposure to diminishing fossil fuel supplies will lead to increasingly volatile global prices.

Northern Ireland being on the peripheral of Europe with no natural fossil fuel resources and at the end of a 4000 mile pipeline from Russia the nearest source of gas or oil is particularly exposed. We have only to witness the recent events between Russia and the Ukraine to understand how serious that exposure is. If Russia turned the gas tap off completely it is likely that Northern Ireland would suffer rolling blackouts within 72 hours. No politicians should allow their country to be that exposed.

Climate change represents the biggest threat to humanity today. If the world carries on with business as usual with energy demand fed by fossil fuels it will result in atmospheric CO2 of 1000 ppm which will lead to a 6oC temperature increase by the end of the century.

This would have catastrophic implications for our grandchildren as they would be confronted with a world in which there would be mass migration in search of food. There would be upheaval and anarchy as those faced with starvation, drought, and disease fight with those who still had resources. This is not Africa we are talking about; this will be the western world, as we know it particularly central USA and the Mediterranean regions.

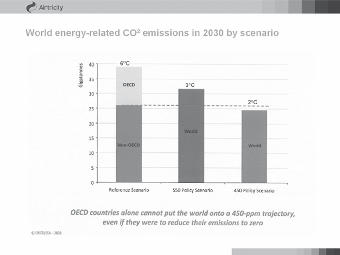

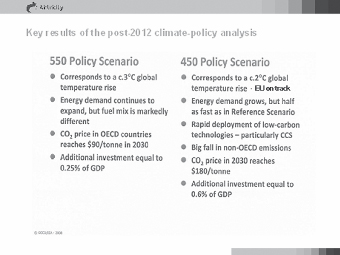

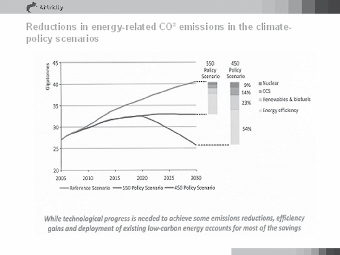

The results of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggest a 450 ppm scenario is necessary to prevent any major tipping points being reached. This would have a corresponding 2 oC temperature increase but would require political leadership, a global approach and rapid deployment of low-carbon technologies. 2 oC could not be achieved by OECD countries alone; it needs to include developing countries especially China and India. The IPCC have produced 2 scenarios, the optimum 2 oC or 450 ppm scenario or the most likely 3 oC or 550 ppm.

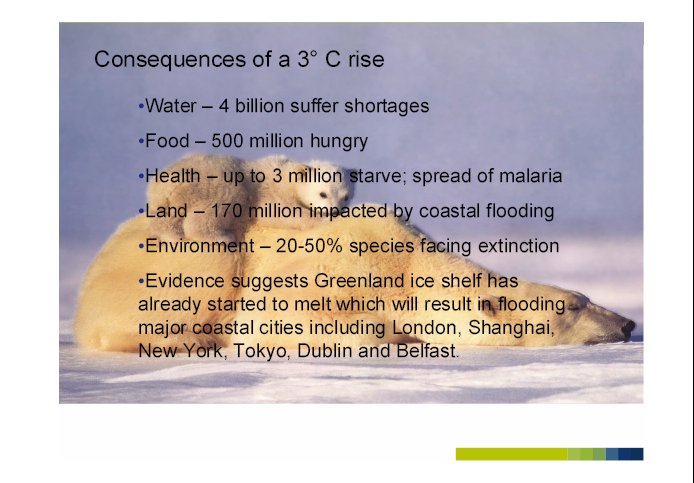

To put these climate change scenarios into perspective, the 550 ppm scenario will result in a 3 oC temperature increase which will lead to 4 billion people suffering water shortages, 500 million going hungry and 170 million impacted upon by coastal flooding, including many in Belfast and Dublin. All leaders across the globe be they in business, politics, science, whatever their field must unite to stop this. Northern Ireland must play its part.

Both scenarios require significant investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies

Those countries that respond to these challenges quickly will not only contribute to resolving the worlds climate change and security of energy supply problems but they will create positions of technological leadership that will create new businesses and wealth which will create employment and improved living standards.

At Airtricity, we see climate change as a business opportunity not a business hindrance! Opportunities will be created in many sectors including energy procurement, waste management, efficient building and insulation technologies, and innovations in transport and engine efficiencies.

Northern Ireland needs to embrace a sustainable future by utilising the skill sets of our bright young people, having industry led research in our universities and exploiting our natural resources for a competitive advantage, i.e.: wind and tidal power. By taking a leadership role we can also benefit from the financial support available from Europe for such activities.

Baglady Productions

28 February 2009

66 Grange Road

Ballymena BT 42 2DU

www.bagladyproductions.org

[028] 25 639609

I, Shirley Lewis, am director of Baglady Productions, a not-for-profit company working to inspire individuals and community to take responsibility for our place on this planet. We have no formal membership, but our message gets out; our website indicates wide support across Northern Ireland, the UK and globally.

I am a member of the Climate Change Coalition [CCC] and have played my part in the discussions about our collective response. My own experience as an environmental campaigner makes enables me fully to endorse the Climate Change Coalition response.

My role is:

(i) to communicate the urgency of action

(ii) to point to the good developments that will accompany this action

(iii) to inspire people in Northern Ireland and around the world to look after this, our beautiful place..

My focus here is, as always, on doing rather than talking. I am always calling for action. We have no time to lose. Not currently employed by government at any level, I am free to say exactly what I think and feel. I continually strive to do so with respect for everyone and everything,

Since my return home to Northern Ireland from Australia in 2002, I’ve been funded 6 times by government*.

In total I’ve managed over £100,000 in cash and a lot more in kind, keeping waste of all kinds to a minimum. I have taken great pleasure in doing much more than was expected at most stages of the 5 years of funding. I knew there was no time to lose.

I’ve visited over 150 schools in Northern Ireland and met hundreds of teachers and thousands of schoolchildren who are bursting with enthusiasm to do something urgent about climate change and other environment issues . They often know, and are prepared to do, much more than their parents.

Their Positive Pester Power [PPP]** skills can get us adults off our proverbials ; through internet and other media they can reach out to other children, and their parents, right around the world. And they can help us make it fun.

I have 7 years experience in living ASAP [As Sustainably as Possible] which means no car, no garage, no oiltank, and much attention to domestic energy saving of all kinds, and means I can make a very strong contribution on all aspects of the spectrum from waste to sustainability. I am writing a play about this.

Response to the terms of reference

(a) To identify initial commitments for Northern Ireland that will ensure it plays a fair and proportionate role as part of the UK in meeting climate change targets.

Baglady comment:

At approx 1.7million people, we in Northern Ireland make up 1/4000th of the world’s population.

Sadly, we use much, much more than our fair share of resources, guzzling up 1000th of what’s available. North and South of the border, our global footprint is about 4 times what it should be [wwf]

[Climate Change Coalition: ‘Northern Ireland’s per capita emissions of 12.83 tonnes compares badly with the UK average of 10.48 tonnes, the global average of 4 tonnes and the global fair share of 1.65 tonnes’]

People somewhere else in the world don’t have enough because of what we’re using and wasting..

This is the true story of climate change - Earth responding negatively to our greed, excess and laziness. Human beings have developed problems of attitude and behaviour which threaten our very existence.

We know we are doing this. Yet we continue to do so, giving all sorts of reasons to justify our failure to change even the most basic of wasteful habits - eg plastic bags, water, energy in all forms, food, paper.... the list is massive and it needs decisive action from the Environment Committee and the NI Assembly.

We can change; we are already changing. It just needs to happen on a broader scale, faster, more efficiently and ideally with a great deal of our fabled Irish creativity and humour. The very smallness of our community, its friendliness and sense of humour all suggest to me that we can quite easily take the lead here. Our children need our support.

I agree with the Climate Change Coalition that:

‘The Assembly should ensure that its voice is heard at the national and international level. It should categorically state its support for an international climate change agreement to limit global warming to no more than 2° Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures (most scientists accept that ‘dangerous climate change’ is much more likely above this temperature increase).

‘The Assembly has accepted that the provisions of the UK Climate Act will be extended to Northern Ireland. [Next, we need] ‘a Northern Ireland Climate Change Act with a legally binding regional target to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050. This is the minimum requirement that will be necessary to play our part in the global attempt to avoid dangerous climate change.’

‘The Executive should set an “intermediate" target for emissions in 2020, a series of legally binding 5 year “carbon budgets" and an annual carbon reduction target at an average of at least 3% per annum. ‘

(b) To consider the necessary actions and a route map for each significant sector in Northern Ireland (energy, transport, agriculture and land use, business, domestic, public sector etc)

Baglady comment:

Action is my forte. It is, oddly enough, the most difficult thing for humans to do - especially in the climate change context.

We now broadly agree: to do nothing is NOT an option. But what to do? and how? how long can we put it off?

We need immediate leadership from our politicians and people at all levels, top to bottom, in government departments.

In my experience, people in political positions and in related government departments often take up their post knowing very little about environment, climate change etc. The knowledge is new, rapidly changing, and highly confronting, eg if you get driven to work in a fuel-inefficient car, like Arlene Foster.

Often by the time these people are fully equipped for the task in hand, they’re moved to a different department. It would be most helpful to ask these people for their insight into how to deal with this information gap.

The people I’ve met with the best skills and least conflict of interest are the scientific community [eg QUB and UU], charities and environment NGOs. They should be trusted more and consulted in greater depth - as you’re doing now.

I personally have access to a wealth of comment on energy, transport etc - and direct experience of living it - it would take weeks or months to tabulate them. Instead, I am finding ways to express what I’ve learned - eg in installing PV cells and thus generating my own electricity to sell back to the grid [!!] - in a way that sucks people in....

(c) To identify the costs associated with meeting these obligations and compare them with the costs that will be incurred if they are not achieved.

Baglady comment: A 12 yr-old boy sees the solar panels on my roof. For weeks, he and his friends plague me with questions about why I have it, what it costs, how it works etc... I tell them all I can; and I add that installing solar panels could be a good, worthwhile and interesting job... this keeps them going for even longer.

Action Renewables: ‘almost 6,000 short term and 400 long term jobs could be sustained in Northern Ireland, exclusively by developing renewable energy within the region.’

Baglady: Our children are almost not needed in a world where machines do most things better, quicker and cheaper than they ever could. Our kids have nothing to do, nothing to look forward to. They become angry, or despairing.

This is costing us huge sums of money in violence, vandalism, medical bills for depression, obesity, prison sentences, the list goes on.

The Climate Change Coalition quotes Northern Ireland’s Chief Medical Officer Michael McBride:

“Current predictions on climate change suggest greater long-term impacts on health than any current public health priority. To preserve health in a changing climate, we need to modify and strengthen the systems we have to adapt to the likely future impacts of global warming. We must tackle this issue on all fronts, reducing our contribution to the problem and responding to the effects of climate change is a shared international responsibility." ‘

Baglady: Meanwhile, my travels around NI show me that it’s in a shocking state of rubbish and waste. We will never have the money to clean it up. But we do have the people. Taking responsibility for our daily life in terms of the basics: shelter, food, water, warmth.... will make a huge difference; and we can measure it.

Further relevant - and encouraging - extracts from the Climate Change Coalition response:

‘The central message [of the Stern Review] is that reducing emissions today will make us better off in the future: one model predicts benefits of up to $2.5 trillion each year if the world shifts to a low carbon path.

‘The renewable sector in Germany supports 170,000 people and existing German government support measures promoting renewable energy could create 130,000 new jobs by 2020 [German environment ministry]

‘Greater than 70,000 jobs could be created in the UK by investing in and developing offshore wind technology. [Carbon Trust]

‘The overall added value of the low carbon energy sector by 2050 could be as high as $3 trillion per year worldwide and... could employ more than 25 million people.’ [Gordon Brown]

‘The Coalition believes that there are strong moral imperatives for Northern Ireland to contribute its fair share of global emissions cuts in order to combat global climate change. Hundreds of millions of people across the globe could lose their lives and livelihoods, up to a third of land-based species may become extinct, immense political instability will occur as people migrate to avoid droughts and floods and compete for scarce resources, and great economic damage will be caused by increasingly extreme weather.

The SNIFFER report on the impacts of climate change on Northern Ireland identified a number of direct effects, mostly negative, on human health, the economy, natural habitats and water resources, for example, the extent of flood risk to existing settlements remains unquantified compared with the situation in Great Britain.

(f) To make recommendations on a public service agreement for the DOE Climate Change Unit’s commitments in the second Programme for Government that will ensure Northern Ireland will meet its climate change obligations.

‘The legal responsibility to deliver the targets set in a Northern Ireland Climate Change Act and through the carbon budgets should fall collectively on the Executive.

Specific responsibilities to deliver the targets set in the Climate Act and in the carbon budgets should be identified in public service agreements for each Northern Ireland department.

A public service agreement should be drafted for the Department of the Environment which would include a commitment to provide information and support to the other departments to help deliver the targets set in a Northern Ireland Climate Change Act and in the carbon budgets. ‘

Baglady comment: The public need to see all government staff, particularly those in the Department of Environment, showing full awareness of their own role and responsibility, in forestalling climate change. Getting rid of the take-away packaged lunches, the heat and light wastage in offices - all these things can be used to build awareness and staff morale.

Individual and group actions in any of these areas needs to be praised and publicised both interdepartmentally and community-wide, so people can learn by example.

Preaching and stats don’t work, how-tos, targets, responses, tables etc do. And always remember: make it fun.

There is huge frustration in the Education Department over Education for Sustainable Development [ESD] Progress there is slowed by steady withdrawal of funding from various bodies specialising in school visits eg Sustainable NI, Action Renewables. Curriculum material appears brilliantly envisaged and practical - but the subject is not examinable. The Sustainable champion in Education has too many other commitments to find sufficent time and energy for this huge job.

I have found that environment in general, and dealing with Climate Change in particular, are very popular subjects with schoolchildren of all ages. Much of the alienation experienced by the less academically promising children vanishes, in the rush to show and share skills acquired in this new and challenging field. Again, it’s fun.

The Climate Change Coalition:

‘The people of Northern Ireland are asking for leadership from the Assembly.

There is a lot of expertise on climate change available in Northern Ireland and many groups are looking to play their part in facilitating moves towards a low carbon economy. The Committee should engage widely and openly.’

Conclusion

September 2009 is a long way away if you consider that we need to reduce our carbon output by 3% per annum. And it’s cumulative; the longer we postpone, the harder it will be to make it up.

Baglady Productions congratulates the Environment Committee on its initiative ini launching this enquiry, and would welcome the opportunity to make a presentation to the Committee if invited.

footnotes:

* first a costs-only Millenium Award, then 2X Ballymena Borough Counci [Environment Weeks 2003,2004] , which led to 2X DoE funding for NEEDabag? campaign with 10 councils [2005] and with 23 councils, 100+ schools and thousands of supermarkets and convenience stores and solid press, radio and TV support. The last funded project, in partnership with jollytv, had us travelling ASAP[ [bus and train where possible] all over N Ireland to film baglady in 16 places. see www.bagladyproductions.org

** Baglady apparently discovered Positive Pester Power in 2006. It was immediately adopted by Down District Council’s Janet McIlvenna and featured on BBC Politics Show. Subsequently praised by Eamon Holmes on BBC Summer Special show 2007

CCC (NI) members:

- ARENA Network

- Baglady Productions

- British Council (Northern Ireland)

- Centre for Global Education

- Chartered Institute of Environmental Health

- Christian Aid

- Concern

- Conservation Volunteers Northern Ireland

- Friends of the Earth

- Green Action

- NICVA

- Northern Ireland Environment Link

- Oxfam Ireland

- RSPB

- Sustainable NI

- Sustrans

- Tearfund

- The National Trust

- TIDY NI

- Tools for Solidarity

- Trocaire

- Ulster Wildlife Trust

- WWF Northern Ireland

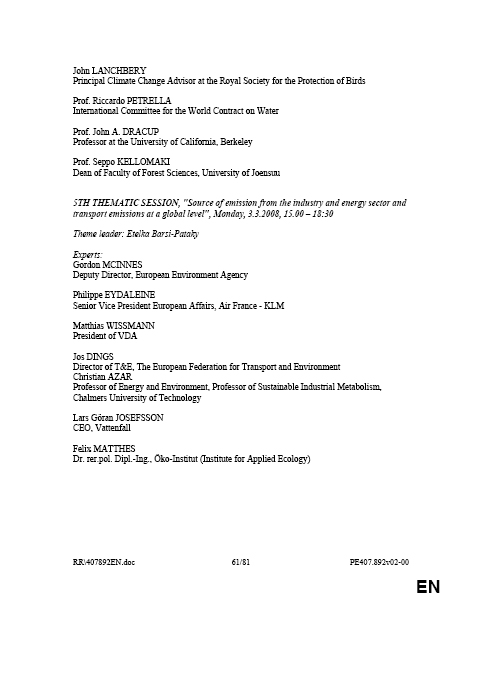

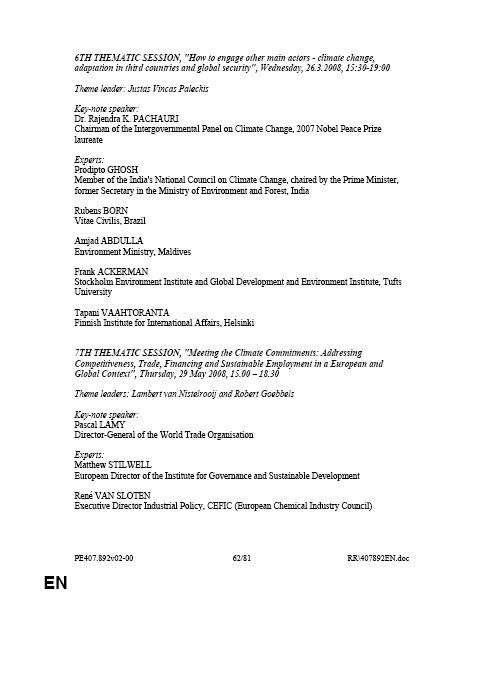

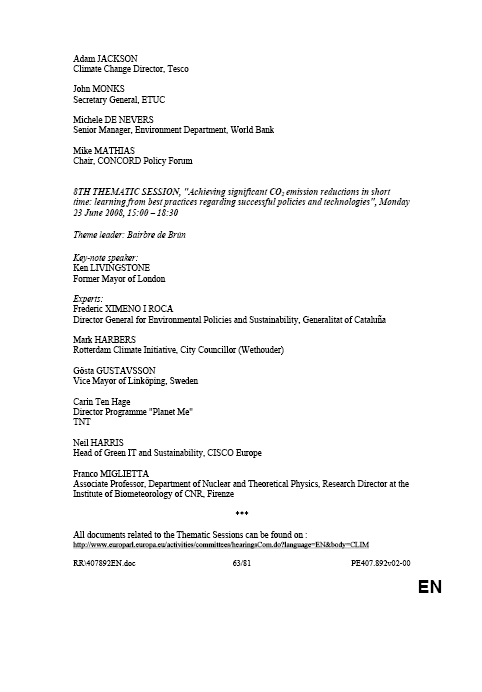

Barbre de Brun MEP

European Parliament

|

2004 |

|

2009 |

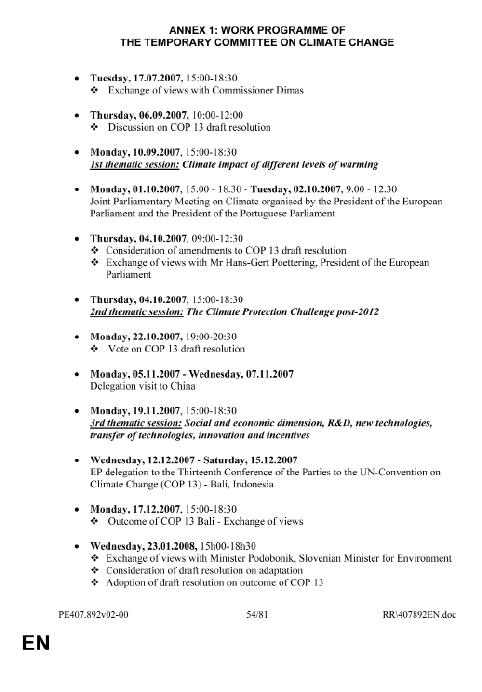

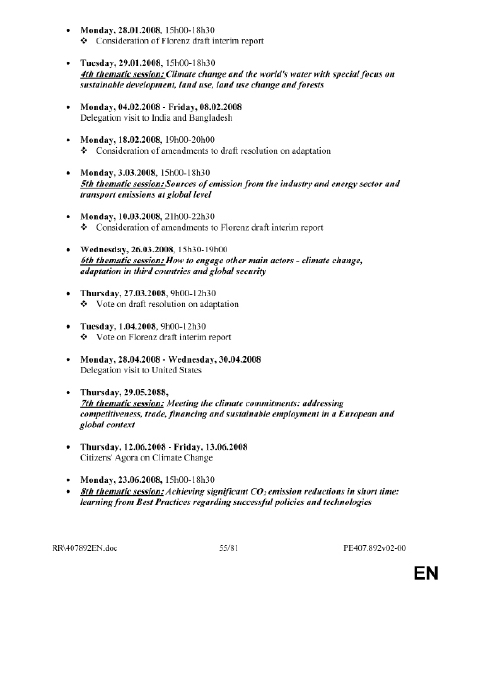

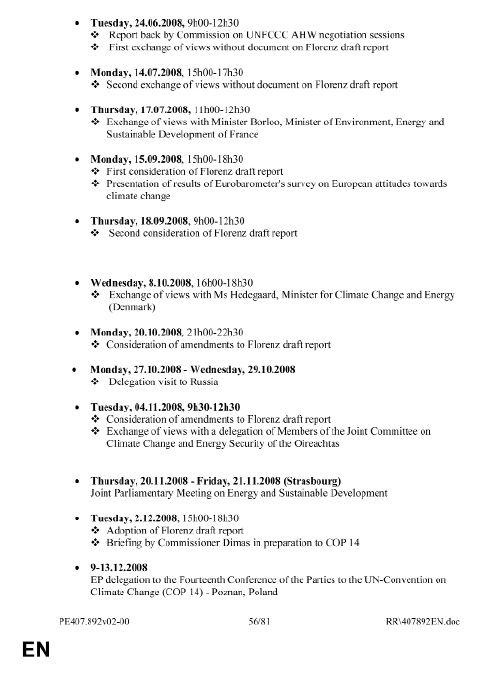

Temporary Committee on Climate Change

14.7.2008

Working Document No. 8

on the 8th Thematic Session “Achieving significant CO2 emission reductions in short time: learning from best practices regarding successful policies and technologies"

Contribution by Bairbre de Brún, Theme leader to the Rapporteur

Temporary Committee on Climate Change

Rapporteur: Karl-Heinz Florenz

Introduction

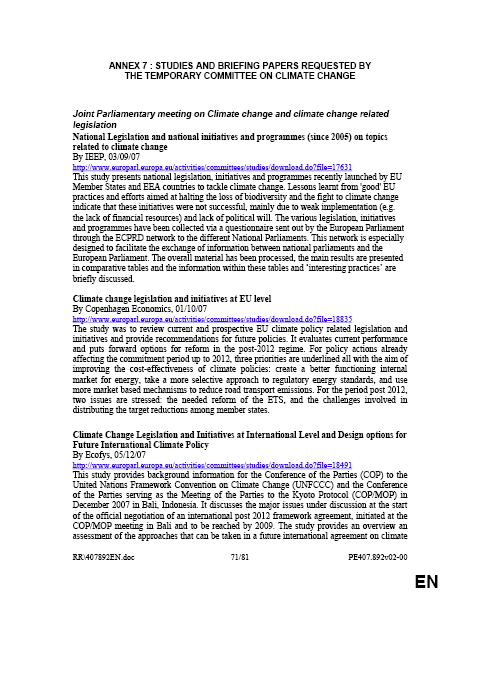

The Temporary Committee on Climate Change (CLIM) held its eighth thematic session on the subject “Achieving significant CO2 emission reductions in short time: learning from best practices regarding successful policies and technologies" on Monday, 23 June 2008, from 15:00-18:30, in the premises of the European Parliament in Brussels, Room PHS 1A 002.[1]

The objective of the eighth session was to gather information on the possibilities to start quickly a coherent policy in order to combat climate change. These policies should not be dependent on R+D nor on possibilities that are not yet available in the market, but focus on existing technology. Together, they should be able to reduce significantly the amount of CO2 emissions.

Opening session and first expert panel

Guido Sacconi, Chairman of the Temporary Committee on Climate Change, opened the event introducing the speakers and the topics to be discussed. Inaugurating the eighth thematic session, the Chairman encouraged the experts to explain the various possibilities concerning the reduction of CO2 emissions.

Karl-Heinz Florenz, Rapporteur for the Temporary Committee on Climate Change asked the experts to deliver solutions that would be immediately applicable and that would produce significant positive results.

Bairbre de Brún, theme leader for the 8th thematic session stated that although climate change is a global challenge, solutions can be found at local level. The successful companies of the future will be green companies. The successful cities will have an urban infrastructure that helps to limit CO2 production.

Key-note speaker and First Expert Panel

Calling climate change “the single biggest problem humanity has faced" the key-note speaker Ken Livingstone said that the tools necessary to halve emissions are already in place. He said that political will and sustainable energy consumption are key requisites and that a successful EU climate change policy will have to involve the pooling of best practices across Europe. In London, said Livingstone, it would be possible to reduce carbon emissions “by 60 percent by 2025 and 80-90 percent by 2050" by using existing technologies.

Ken Livingstone had to convince the British government to change the regulatory framework to locally generated power, because the present mass power generation far from the users creates a waste of energy of 65 % in cooling and transport. When local power stations were used, the heat could also be applied usefully so that only 15 % is lost, which makes 50 % difference or 30 percent of the total.

The other 30 % of gains can come from lifestyle changes: never waste anything: re-use waste, never waste light, use efficient fridges, washing machines and other white goods, and properly insulate homes. If each city advances on every front - accumulating best practices from cities worldwide - the 60% reduction in London could be reproduced all over Europe.

Ken Livingstone when Mayor of London was instrumental in establishing the C40 group of the world’s largest cities, working in partnership with the Clinton Foundation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions among cities. The Clinton Foundation used its bargaining power to negotiate with big companies on the subject of retrofitting buildings. As the number of bigger projects increased, so did demand and thus the whole market, and prices could be brought down. Further there was a negotiation on special financing arrangements. The companies would do the work upfront without charging and would be paid back from 80 % of the energy savings, leaving 20 % for the “clients". The congestion charge was also important as will be the introduction of a low emission zone in London with tariffs on certain lorries not complying with standards.

European legislation is helping local government work more in a more environment-friendly way. Without regulation in the EU, the slowest would even be slower.

Frederic Ximeno i Rocca, Director General for Environmental Policies and Sustainability, Generalitat of Cataluña, spoke on the experiences of Catalonia, and in particular on the hugely participatory process that led to the development of their 2008-2012 Catalan Plan to Mitigate Climate Change. The aim of the government of Catalonia is to prevent the emission of 5.33m tonnes of CO2 equivalent on a yearly average during the Kyoto protocol period.

A Catalan office for combating climate change was created and citizens were invited to take part in the Catalan Convention on Climate Change. More than 800 people and around 500 different organisations were involved. More than 1000 proposals were examined, many of them highly developed. They adopted a structured approach involving not only meetings but also internet and media programmes, integrating all sectors of the government as well as civil society and resulting in clear objectives. The focal point of the plan’s efforts is on mitigating emissions from sectors not included in the EU’s Emissions Trading Directive, and which contribute 65% of emissions including mobility, waste, agriculture, the residential sector, retail, construction, industry and energy. The plan also includes a programme for the sectors covered in the directive, as well as a programme of actions aimed at driving research, awareness-raising and participation. The government of Catalonia considers that the participatory process has helped particularly to increase awareness, motivation and support by the population for the climate programme.

Mark Harbers, City Councillor (Wethouder) of Rotterdam, presented the Rotterdam Climate Initiative, which intends to achieve a 50% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2025, compared with the level in 1990. This initiative was partly inspired by Rotterdam’s participation in the international climate program of former US president Bill Clinton. Within this programme, Rotterdam leads the way in the subprogramme focused especially on world ports. Both the government and the corporate sector are represented in the Rotterdam Climate Initiative. This concerted approach allows rapid progress and it has created enormous action power.

Innovative entrepreneurs come up with clever ideas for alternative sources of energy. Sizeable transport companies, such as TNT, the Rotterdam taxi centre, and the municipal transport company all contribute their own programmes to enhance the sustainability of their fleet. Companies that emit a lot of CO2 capture this CO2 and transport it to the greenhouse district nearby, the Westland, where market gardeners use it to grow tomatoes. Housing associations are working hard to enhance the sustainability of their housing stock, and more and more property developers decide to build only sustainable buildings from now on.

The municipality, therefore, mainly needs to serve as a catalyst, a booster, a trailblazer. They remove barriers, for instance by helping to provide new forms of financing to improve the possibilities for sustainability investments. They detect initiatives and movements, identify frontrunners, place good examples on display for everyone to see, and bring parties together. They have reached agreements with developers, building contractors, architects and investors on sustainable construction in Rotterdam. Together with forty other large port cities they will conclude agreements on cleaner forms of shipping. They are conducting experiments concerning the possibilities of introducing LED lighting in the city centre of Rotterdam. And they invest in innovation, for instance in the further development of Formula Zero (cars running on hydrogen), as well as new types of wind energy. Last winter, they arranged for the delivery to over 300,000 homes, of two low-energy light bulbs. All of these low-energy light bulbs together result in a total saving of 50,000 tons of CO2.

Gösta Gustavsson, Vice Mayor of Linköping in Sweden talked about the initiatives and best practices in his city, including best practice transport initiatives, promoting public transport and halving the transport of goods through pooling. Linköping applies climate and environmental requirements to all purchases and communicates climate issues to employees, elected representatives, residents and businesses in the municipality. Bicycle traffic amounts to 30% of all traffic and there is more than 40km of pedestrian and bicycle paths.

Linköping is today one of Europe’s leading biogas cities and has fifteen years of experience of the processing, production and development of bio-methane, from organic matter such as waste from slaughterhouses and household food waste, which is used in city buses, refuse collection vehicles, almost all taxis, and the municipal car pool. There are three production plants, thirteen public fuelling stations, and one bus depot. Bio-methane sales represent 6% of the total vehicle fuel volume in Linköping. Bio-fertilizer is sold to farmers and replaces fossil fertilizers. Linköping will also try to run a train on biogas. Organic waste is turned to biogas with the advantage of a reduction of weight and volume of the “waste mountain".

Other initiatives mentioned include the district heating and cooling grid, a sorting plant/recycle station, landfill elimination and initiatives that seek to involve all citizens and the private sector. Linköping’s economic track record shows that the municipality and society has benefited. There must be long term targets and rules because companies and citizens must trust the city. That is the secret and the EU has, until now, been very helpful in creating this stable set of conditions.

In the discussion after the first expert presentations the following Members took part: Riitta Myller, Roberto Musacchio, Karl-Heinz Florenz, Catherine Guy-Quint, Vittorio Prodi, and Guido Sacconi. The discussion focussed on an eventual binding target for increased energy efficiency, the input of the non-used electrical power into the public grid, the stimulating power of European rules, the use of waste and the effects of measures on transport and mobility.

Key note speaker Ken Livingstone answered that there are still problems of congestion but that there is a shift away from cars usage to public transport and cycling. There are 50 % more bus passengers and many more buses. Incineration must be skipped in order to use more efficient ways of getting rid of waste. EU regulations always worked best and Ken Livingstone asks the Members to be tougher.

Frederic Ximeno I Roca mentions that Spain has not yet achieved its goals on CO2 reduction. EU regulation helps to put environmental objectives into mainstream SMEs take many initiatives in Barcelona because there is now more awareness. There are seventy-three measures to reduce pollution. Although drivers did not react well to 80 kilometres per hour speed limit, there are fewer accidents, less petrol use and less CO2-emissions.

Mark Harbers states that there is a very good information-exchange including the communication of experiences. Bigger companies know that it is in their economic interest to invest in CO2 reductions but SMEs are somewhat lagging behind. In the field of heat-power and residual heat there are extensions of district-heating. EU regulation is very important to make progress and Mark Harbers advocated regulation on the waste of heat, particularly because heat is not an unuseful waste.

Gösta Gustavsson. said that in Linköping there is no incineration of what can be re-used or recycled. A municipal company is responsible for district-heating. If you start with biogas you need to have it, you need to have the infrastructure and the users, and all that at the same time.

Second Expert Panel

Guido Sacconi welcomed the second expert panel consisted of Carin ten Hage, director of “Planet me" (the environment programme) within TNT, Neil Harris, Head of Green IT and Sustainability, CISCO Europe and Franco Miglietta, Associate Professor, Department of Nuclear and Theoretical Physics, Research Director at the Institute of Biometeorology of CNR, Firenze.

Carin Ten Hage stated that the overall ambition of TNT is a continuous reduction of the carbon intensity of operations through a three stage procedure. The first Count Carbon is to count carbon and integrate carbon management in business processes, measuring the impact of initiatives, setting targets, improving internal carbon reporting, developing a framework for effective carbon management and providing accurate CO2 information to customer level. The second part Code Orange touches on every aspect of business, including aviation, buildings, business travel, company cars, green investment, operational vehicles, procurement and partnering with customers. The company builds and implements a global fuel and energy efficiency programme, develops a subcontractor strategy, and purchases green electricity for TNT’s European operations. TNT will include CO2 among the principal criteria in their budget and investment process. They will also implement a green company car fleet and introduce an additional cash incentive for employees who choose cars that produce less than 120g/Co2 per kilometre. The company’s trucks and vans generate some 23% of total emissions and they are running a number of projects for the use of alternative fuels such as the use of electric lorries, pure bio diesel lorries, hybrid trucks, and even in bio diesel-blend trucks in India. The third part Choose Orange is a voluntary programme that aims to engage all employees and their extended family by educating, engaging and motivating employees on fuel efficient driving through the “Drive me" challenge, for example and through educating the next generation through the Planet Me Game.

Neil Harris, Head of Green Technology and Innovation for CISCO Europe says it is the responsibility of every industry to be greener. The Cisco green programme will by 2012 result in a 25 % reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Cisco is a partner in the Clinton Global Initiative. ICT technologies account for a very small part of the world’s technologies, but they can provide solutions to help other technologies work more effectively. Cisco works to curb its own company’s greenhouse gas emissions through an eco drive that includes the measurement of energy flows, allowing machines to shut down when not in use and recycling material consumed in offices. The process to find the necessary reductions is to monitor, manage and reduce, as for electricity use in offices, appliances in homes, or traffic flows in cities. Other solutions for customers can include ICT and Ethernet to the factory floor for heavy industries such as steel work and cement factories and Smart grids for power generation and transmission. ICT solutions use energy but can also avoid the use of energy through the use of collaboration technology such as TelePresence software to allow for telecommuting thus reducing the need for business travel by employees, partners and customers. Connected Urban development is a Cisco initiative working with cities on urban design for better sustainability. It began in three cities San Francisco, Seoul and Amsterdam with a total Cisco investment of $15m and expanded to Birmingham, Hamburg, Lisbon and Madrid. The Amsterdam project alone is to save 76 thousand tonnes of CO2 over five years.

Franco Miglietta. Associate Professor, Department of Nuclear and Theoretical Physics, Research Director at the Institute of Biometeorology of CNR, Firenze, indicated the obvious problem: we have too much CO2 so the question is of how to make this carbon useful. His speech on “Biochar in agriculture for residue management, energy production and Carbon sequestration: a win to win strategy" intended to find solutions to that problem. Investigators found a dark type of soil in Brazil and this dark soil dates back to pre-colonial times. Charcoal was used as fertilizer, it made the plot very fertile and the result is a remaining black-coloured soil. Biochar is green charcoal. Vegetable charcoal remains in the soils for thousands of years, improves the water dynamics of the soil, remains active as fertilizer and the production by pirolyses/distillation also produces energy . You can make it out of plant waste. There are thus three win situations: substitution of a portion of fertilizers, sustainable land-use and reduction of off-site pollution.

In the discussion after the second round of expert presentations the following Members took part: Riitta Myller, Vittorio Prodi, Karl-Heinz Florenz and Guido Sacconi. The discussion focussed on the package which parliament should give its opinion on, the availability of plant-matter necessary for the production of biochar and other aspects of the production of biochar.

Carin Ten Hage stated that business needs a real value put on carbon emissions because then they will invest in new technologies. ETS must be transparent, must have the same standards for the whole economy. Businesses need consistent and pragmatic policies. Neil Harris answered that in the ICT industry we work a great deal on energy efficiency by ICT and that will contribute to solving the CO2 problem. Franco Miglietta gave an example of a farmer. On 1ha of land the outcome of 1 year could be an emission of 30 tons of CO2.Ten tons would lead to food to be consumed, 20 tons could be included in the waste. This waste should either be burned or it can be used to produce organic charcoal, with all the advantages. It is important that it is used and that there is a legislative framework. One can calculate how much CO2 is taken from the atmosphere. His opinion is that planting trees will create mitigation, but not much. In farming and biochar the result would be easier to calculate and more significant.

Bairbre de Brún, theme leader, stressed that speakers from both the public sector and business are for EU regulation. No sign of fear for employment has been shown, on the contrary the indications were that through the measures to combat climate change a lot of work and thus employment can be created. But the most important conclusion is bringing people with you. Every participant in the thematic session stressed that motivation is a very important factor.

Even though climate change in an urgent issue not many of our cities and governments are sharing the information that is out there.

Karl-Heinz Florenz, rapporteur, pointed out that the ideas of the C40, executed in London and other cities where an innovative financing plan was introduced where the works were done by and financed by industry from future gains were very interesting. They could certainly be more widely applied and might increase demand and thus lead to lower prices of innovative products. Internalization of external cost will lead to fair situation. As far as traffic is concerned, we are close to traffic collapse and ideas must be developed to improve the situation. If you collect and implement best practice from each area of the world you can advance significantly.

Conclusions by the Theme Leader:

On the basis of the presentations and the discussions held at the eighth thematic session the Theme Leader draws the following key conclusions:

1. A sufficient mix of technologies exists to make rapid CO2 reductions possible. EU policies act as a spur to the adoption and use of these technologies and can help on a national, local and regional level to achieve rapid reductions of CO2 emissions.

2. Information on climate issues and climate solutions is all important. Businesses, cities and governments will be inspired to action if they know that what they regard as ‘new’ technologies and policies are already standard practice in other places, and are producing results.

3. An action plan with clear objectives and targets will aid progress, drawing on widespread input from a range of participants and learning from best practices elsewhere. The challenge is global but individual and local actions produce solutions. No place is too small to make a contribution.

4. Motivating citizens, employees, business and other stakeholders is important in getting action and changing habits, attitudes, practices and lifestyles. Networking and information exchange will help local and regional governments in developing the necessary approaches.

5. Initiatives such as the distribution of two energy efficient lightbulbs to every household address mentioned in the presentations can be as important in raising awareness as the use of documents or media advertising campaigns.

6. Amongst the best practices mentioned in the thematic session were efficiency measures such as retrofitting of houses and offices, more sustainable buildings, better traffic planning, more efficient lighting, re-using and re-cycling, more efficient use of water, increased public transport, walking and cycling, use of ICT to reduce travel and to improve the effectiveness of processes in industry, monitoring the carbon footprint of the business or municipality, and a move to renewables. There are administrative and motivational barriers to be overcome, but the overall effect of these measures is a positive financial gain, less CO2 emissions and a significant rise in employment.

7. Sustainability and economic development are not opposing factors; they are opportunities for mutual reinforcement. Quality of life and employment will not suffer from actions to combat climat change.

8. There is a greater willingness to contribute to tackling climate change than is generally thought, including among business. Clear legislation and ambitious long-term emission requirements from the EU aid stability in planning as well as intermediate targets and clear legislation at member state level.

9. Local and regional level governments could set stricter, binding targets than the 20/30 % reduction envisaged by the climate package of the European Commission. However, as cities and regions differ greatly, those targets should be tailored to the regional or urban level.

10. Innovative financing programmes must play a role in order to overcome barriers

11. Waste management and the use of waste are crucial for urban areas. The use of waste in an environmentally sustainable manner can create a supply of biogas, energy, and heat, relatively close to users in the urban area. As examples have shown, waste management can provide financial gains, less CO2 and a positive effect on employment.

12. Large companies can make changes not only to their own practices but, through engagement with subcontractors and suppliers, can influence the behaviour of SMEs also. They can also engage with their employees about lifestyle changes outside the workplace.

[1] Please note that some presentations delivered at the thematic session are available at the CLIM-Webpage at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/comparl/tempcom/clim/sessions/default_en.htm

Bairbre de Brún MEP

February 2009

Overview

Sinn Féin recognises the potentially disastrous impact of climate change on our environment and society. We believe that effectively tackling climate change brings opportunities as well as challenges.

In the Sinn Féin submission to the Programme for Government (PfG) we identified recommendations relating to a number of Departments on how to tackle Climate Change.

The Executive should commit to reducing our emissions by at least 30% from their 1990 level by 2020. The rate of reduction should be at least 3% per annum. There also needs to be periodic targets set by the Executive for the period leading up to 2020, and proposals made to compensate where emissions reductions targets have not been met.

The European Union has introduced a mandatory target of 20% renewable energy-use by 2020, and we should play our part in meeting that target. We believe that Ireland is well-placed to be at the centre of a new, green economy, if the political will exists, because of our potential abundance of wind and wave energy as well as our historic lack of heavy industrialisation compared to other developed countries. Sinn Féin also supports the use of biomass and solar energies as a part of our renewable energy production.

Sinn Féin supports waste to energy solutions where these involve production of electricity from Mechanical-Biological Treatment and Anaerobic Digestion processes in Combined Heat and Power plants, and do not involve incineration or other thermal waste treatment.

Within an all-Ireland framework, Sinn Féin also supports moves towards energy independence and decentralisation in energy production. We believe the Assembly Executive and the Irish Government should put renewable energy production at the heart of all-Ireland economic planning in order to allow a prosperous all-island economy to become a world leader in renewable energy production.

Underpinning this approach should be an integrated strategy across government departments and in conjunction with local councils, accompanied by targets, goals and monitoring mechanisms.

Initial commitments

Climate change is not just the major political challenge of our time; the worst impacts of climate change constitute a great social, environmental and economic threat. We cannot afford to fail in addressing the very real danger of climate change.

While much political attention is rightly focused on bringing down the emissions that cause climate change, we also need to work on adapting to climate change. Even if we agree strict new emission reduction standards, we will still need to deal with changing climate conditions for decades to come. We need to be prepared.

The Assembly has given its consent for the provisions of the Climate Change Act 2008 to apply to the North of Ireland. There is an opportunity through new local legislation and a new integrated Executive policy to take forward a strategic response to setting and meeting specific targets for the North of Ireland on reducing CO2 emissions and responding the economic challenges facing us.

A detailed integrated Executive strategy to setting out how we are going to meet our carbon emissions targets and adapt to Climate Change should spell out how each sector of the economy and society can contribute to reducing these emissions. The Scottish Climate Bill shows the direction that we can and should go, and we should take account of suggestions being made in Scotland for further strengthening of the Scottish legislation.

Sinn Féin believe the Executive could give a greater focus on a number of key areas, including:

- A reduction in energy consumption;

- The development of renewables; and

- Decentralisation of the energy infrastructure.

The Executive needs to reassess its options for tackling rising energy demand, meeting energy efficiency and renewable energy targets and reducing CO2 emissions. A tremendous opportunity exists to put the production and use of renewable energy at the heart of the Executive economic development strategy.

Investing in new technologies and moving much more decisively to renewable energies as well as energy efficiency can create more jobs and lower energy bills. Renewable energy in particular could be developed in an all-Ireland energy market.

The Executive needs to be pro-active in its support for low carbon innovation. Actions can and should be taken across departments, including in the fields of enterprise and job creation, energy, transport, agriculture and land use, waste management, planning, tourism, fisheries and forestry, education and training and finance and investment. Closer co-operation and co-ordination between Departments is needed and between the relevant Assembly Committees.

I also strongly support the call for building regulations here to be revised to promote the use of renewable energy technologies.

International and European context

2009 is a key year in setting out the global response to Climate Change with the UN Conference in Copenhagen at the end of the year due to agree new targets and actions to tackle Climate Change.

The European Parliament Climate and Energy Package has also given effect to the targets set by the EU last year to have 20% renewable energy, 20% energy efficiency and a 20%-30% reduction in emissions relative to the 1990 level by 2020. This represents an unprecedented attempt to tackle the causes and consequences of climate change. Sinn Féin supports all measures at local, national, EU and indeed at global level through the UN climate talks which can set the necessary binding targets for CO2 reductions.

There are some very disappointing elements in the EU package such as the possibility for member states to export the majority of their emissions reductions actions to countries outside the EU and the complete failure to stand up to the automobile industry and impose strict reductions in CO2 emissions from passenger cars. On the other hand the measures on renewable energy and on fuel quality and the improvements to the Emissions Trading Scheme represent movement in the right direction.

Efforts to decarbonise the economy will offer significant business opportunities in the time ahead and we should introduce fiscal incentives to develop research into clean technologies.

The European Commission has announced, as part of its European Economic Recovery Plan that it will allow EU funds be used for energy-efficiency projects in low-income housing. This is something Sinn Féin argued strongly for. The Executive should make this part of their strategy to deal with fuel poverty and to tackle climate change.

Sinn Féin also believe that all investments and policies in Europe should be ‘disaster and climate proof’. We have recently seen a stark example of a lack of local disaster-proofing in Stoneyford where a housing estate, built on a flood plain, has experienced repeated serious flooding, making the houses uninhabitable. We have to ensure that preventative measures are in place and that protection structures are well maintained. We also need to have strong policy controls on where building takes place.

In 2007 the European Parliament set up a Temporary Committee on Climate Change, vested with a number of powers including to formulate proposals on the EU’s future integrated policy on climate change. It held a number of thematic sessions, and I was theme leader for the 8th Thematic Session “Achieving significant CO2 emission reductions in short time: learning from best practices regarding successful policies and technologies"

Amongst the best practices mentioned in the thematic session were efficiency measures such as retrofitting of houses and offices, more sustainable buildings, better traffic planning, more efficient lighting, re-using and re-cycling, more efficient use of water, increased public transport, walking and cycling, use of ICT to reduce travel and to improve the effectiveness of processes in industry, monitoring the carbon footprint of the business or municipality, and a move to renewables. There are administrative and motivational barriers to be overcome, but the overall effect of these measures is a positive financial gain, less CO2 emissions and a significant rise in employment.

I attach the report of that session, Working Document No 8 of the Temporary Committee on Climate Change, as an annex to this submission.

The concluding report of the European Parliament Temporary Committee on Climate Change emphasised that tackling climate change will help to create new jobs in new technologies, combat energy poverty and dependency on imported fossil fuel and provide social benefits for citizens. It also calls for a ‘climate audit’ so that EU budget lines can be adapted in line with the requirements of climate policy, as well as tackling the question of allocating unused existing EU funds for climate policies. The report, which has since been adopted by the whole parliament in a somewhat amended form, contains useful suggestions in a range of areas, which could provide a good starting point for discussion and policy-making. I therefore attach a copy of that report also, (Appendix I) the European Parliament resolution of 4 February 2009 on “2050: The future begins today – Recommendations for the EU’s future integrated policy on climate change" (2008/2105(INI) )

Executive Action Plan on Climate Change

Binding domestic legislation which incorporates emission reduction targets can go some way to address the affects of climate change at home and throughout the world. A local Climate Change Bill with annual appraisals that places the emphasis on action at local and all-Ireland level would help deliver long term sustainable environmental development that positions climate change as a priority policy concern. Such a bill could also encourage initiatives involving unions and the workforce in negotiated green workplace agreements to cut carbon footprints.

Engaging with business as well as the public sector makes a lot of sense. Large companies can make changes not only to their own practices but, through engagement with subcontractors and suppliers, can influence the behaviour of SMEs also. They can also engage with their employees about lifestyle changes outside the workplace.

All public sector procurement, especially the Investment Strategy (ISNI) should have robust components built in to underpin targets for reducing CO2 emissions and respond to the impact of Climate Change.

As stated above, actions can and should be taken across departments, including in the fields of enterprise and job creation, energy, transport, agriculture and land use, waste management, planning, tourism, fisheries and forestry, education and training and finance and investment. Closer co-operation and co-ordination between Departments is needed and between the relevant Assembly Committees also.

In terms of adaptation to the climate change we already know will take place, we need to take account of the 2007 report of the Scotland and Northern Ireland Forum for Environmental Research (SNIFFER) ‘Preparing for a Changing Climate in Northern Ireland’

Action needs to happen now and should not be left until the deadline for some of the longer-term targets looms. Actions should be incorporated into the priorities of the Departments and there should be annual assessments made of progress towards reaching those targets.

Targets

Sinn Féin proposes that both governments in Ireland set legally binding targets of reducing CO2 emissions by at least 80% on 1990 levels by 2050. The key to achieving this locally will be an agreed approach across all Stormont departments on how to build a low carbon economy. This will include promoting energy efficiency, better waste management, investing in renewable energy sources such as wind, tidal and solar, and expanding public transport.

Sinn Féin believes that the Executive should commit to reducing emissions by at least 30% from their 1990 level by 2020. The rate of reduction should be at least 3% per annum.

There need to be periodic targets set by the Executive for the period leading up to 2020. There needs to be detail about how we are going to meet carbon emission targets and how this will affect policy in different departments.

The Committee established under the Climate Change Act 2008 should also be asked for advice with regard to targets.

The Carbon Trust has set out a number of areas for action and Sinn Féin would broadly support these; including:

- Investing in industrial energy efficiency

- Transforming building design and construction

- Planning for sustainable housing development

- Decarbonising the electricity supply industry

- Developing the skills base

- Changing attitudes

- Exchanging best practice, solutions and ideas

- Stimulating innovation and product development; and

- Exploring new technology options

There should be a specific target for low carbon, good quality, well-insulated, energy efficient, affordable housing.

We should also use the expertise of other EU member states, through the cross-border, territorial or interregional programmes, through the EU Task Force and through the 2009 regional development OPEN DAYS in Brussels. We should also use the expertise gained to date in this field at local government level through the Interreg programme.

Green Cities

Cities are an obvious place where energy efficiency needs to be secured, and housing is a major area where this efficiency can be maximised. There should be a specific target for low carbon affordable housing, and this should apply to existing as well as new housing. High building standards should be set in regard to building new homes, with energy efficiency at the core. The same high standards should apply to new public buildings and other structures.

Reaching the targets set by the EU, known as the 20/20/20 targets, will require the development of more ‘Green Cities’. 80% of the EU’s population live in cities or urban areas. Sustainable development models need to be applied to all urban planning.

Transport

In transport there area number of necessary shifts in policy which we need to get to grips with. Decades of underinvestment in our transport services mean a culture of car dependency has evolved. This dependency must be broken by providing efficient and sustainable public transport networks in cities, towns and rural areas.

We need to provide accessible, efficient and integrated public transport provision through increased investment in bus and rail network services in urban and rural communities across the north.

Cities and urban areas in the EU produce 40% of the greenhouse gas emissions in transport. Most city dwellers travel only relatively small distances each day yet many travel in private transport based on petroleum fuels. In an effort to reduce transport’s burden on our environment, the EU as part of the climate package, passed a directive which will limit the CO2 emissions from cars.

The EU is also encouraging the use of green procurement with regard to local government vehicles. We must look at ways of facilitating the roll-out of such green procurement here.

A small company in a remote rural area of County Mayo in Ireland developed “Adaptive Intelligent Street Lighting" that allows for remote monitoring of electrical power consumption, individual control and monitoring of each street light and remote dimming capabilities depending on the amount of traffic. These have been installed worldwide, including Oslo, Paris and parts of Asia. Oslo has 10,000 intelligent street lights.

Energy Supply

In terms of energy, the question of security of energy supply is important to any economy and society. Self-sufficiency should be aimed for as much as practicably possible, and we should aim for decentralisation of the energy structure.

In Ireland’s case this means the greatest possible use of our own resources such as solar, wind and tidal power and the development of energy saving, resource-efficient, renewable and low emission technologies.

By helping to meet our share of the European Union target of achieving 20 % of energy from renewable sources such as wind and tidal power as well as solar power, we can boost the local economy, and create jobs while meeting the challenge of climate change. We have wind, wave and tidal resources here and we have some great individual projects. We also have the possibility to work on cross-border projects. The Executive must provide the push and the incentives for the development of renewables on both a small-scale and large scale, and to move beyond individual projects to put the development of renewable energy firmly centre stage in our economic development plans.

We should reject the notion that nuclear energy has any part to play in meeting our energy needs.

In particular the opening up of an all-Ireland energy market could help bring down prices, particularly for electricity. We would also be in a better position to benefit from a new green deal to help re-launch the global economy.

We should also look at some of the work done by DARD and the Agriculture and Rural Development Committee in terms of renewable energy.

Reducing our Carbon footprint

While we are working towards such self sufficiency, we can and should take simple actions in our own lives to reduce our own “carbon footprints" and lead by example - use energy efficient electrical appliances, low energy light bulbs, resist leaving electrical items on standby, shop locally, avoid over packaged goods, have properly insulated homes, move to renewable energy and car share to work where walking, cycling or public transport is not a viable option.

Energy saving through simple steps such as insulating older homes and commercial properties must also be addressed. The ban on incandescent light bulbs should be supported with those on low incomes being supported during the phasing out process. Awareness raising programmes and incentive initiatives for business are to be encouraged and built upon.

Protecting our Environment

Protecting our natural environment will also pay dividends in the fight to reduce our emissions. Planting trees protecting vital carbon sinks are just two examples. Agriculture also has a part to play and there is a need to find a way to create sustainable livestock production. Biomass and short rotation coppice willow has also made a contribution in some areas.

Both mitigation and adaptation measures need to look very specifically at the question of biodiversity and habitats.

We also need to look at the role of waste management and the contribution that waste prevention, minimisation and recycling can play in reducing emissions.

Working with local government

Local authorities also need to grab hold of this issue as Dublin City Council has done on Sinn Féin’s initiative. Dublin has adopted a Climate Change Strategy with a focus on reduction, reuse and recycling. This type of local action needs to be replicated across Ireland. One of the best aspects of this Strategy is its coherence. Waste management, transport, planning, energy generation and biodiversity are linked within the strategy and not treated as individual phenomena.

This type of joined-up thinking also shows where Assembly strategy and legislation could usefully encourage coordination of policy areas.

Attitudinal change is the most important element required in tackling climate change. This change can come from the bottom-up as was done by Dublin City Council and the many excellent environmental activists and organisations we have but making this change at the very top at government level can only be ensured through legislation that places the emphasis on action at national and local level.

The world economy is moving to meet this challenge and the Executive needs to ensure that we don’t get left behind.

Housing and Planning

There should be a specific target for low carbon, good quality, well-insulated, energy efficient, affordable housing. In this regard we should take account of the 2008 House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee report on Existing Housing and Climate Change.

High building standards should be set in regard to building new homes, with energy efficiency at the core. The same high standards should apply to new public buildings and other structures. This is important for meeting our emissions targets as well as for tackling fuel poverty.

There should also be minimum standards for homes and a major programme of insulation and energy efficiency as a first step. There is a need for a cross-departmental action to ensure greater fuel efficiency in existing homes, including improvements to insulation schemes. Such a strategy could tackle three major issues in tandem - energy efficiency in relation to climate change, fuel poverty and the downturn in the building industry.

Costs

There is undoubtedly a cost to the measures that need to be taken. However the successful economies of the future will be green economies and there will be significant extra cost to our economy if we are left behind. Moreover, the Stern Report indicates that extreme weather could reduce global gross domestic product (GDP) by up to 1% and that a two to three degrees Celsius rise in temperatures could reduce global economic output by 3%

We also need to offset against the cost of measures we take the considerable potential benefits to the local economy in embracing green jobs and technologies. Across Europe this is identified as a key focus for action on climate change and

as part of a wider response to the current financial challenges.

In presenting the proposed Climate and Energy Package to the European Parliament in January 2008, Commission President Barroso described it as “an opportunity that should create thousands of new businesses and millions of jobs in Europe,"

Action Renewables estimated that almost 6,000 short term and 400 long term jobs could be sustained in the North of Ireland, exclusively by developing renewable energy here.

Assembly legislation

The Executive should introduce its own legislation in the form of a Climate Change Act for the North of Ireland that includes a legally binding regional target to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by at least 30% from their 1990 level by 2020 and by at least 80% from 1990 levels by 2050. We should also introduce legislation to include a tax on plastic bags, and also to tackle the problem of packaging waste.

British Wind Energy Association and

Irish Wind Energy Association

20 February 2009

Summary Points

The British Wind Energy Association (BWEA) and the Irish Wind Energy Association (IWEA) welcome the Environment Committee’s Inquiry into Climate Change. The Committee is right to focus its Inquiry at identifying how Northern Ireland can play its part in tackling climate change. The scientific and economic rationales for addressing human impact on climate change is well established and widely accepted. The time for action is now.

IWEA and BWEA represent the interests of the renewable energy industry in Northern Ireland, Ireland and Great Britain. Through this submission, we will demonstrate the necessary role that wind, wave and tidal technologies will be required to play in order to meet existing climate change objectives, and provide guidance as to how the Assembly can facilitate the deliver of renewable energy and climate change targets. We very much welcome the opportunity to submit evidence at this stage and look forward to engaging with you further.

Northern Ireland can positively contribute to both the European and UK Carbon targets in two main ways. Firstly, taking advantage of the natural resources available to Northern Ireland will make an appreciable contribution to these targets. The UK has a rich variety of renewable energy resource, including 40% Europe’s wind resource. Northern Ireland has a significant share of this resource, with one of the greatest wind resources in Europe. As such, Northern Ireland has a real opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to reducing carbon-dioxide emissions through renewable energy, while meeting Northern Ireland’s energy demands and delivering a cleaner local environment.

As the world moves towards a low-carbon economy the price of carbon will increase. Northern Ireland should not be left behind but should embrace this approach; indeed Northern Ireland has the potential to be a world leader in the ever growing green economy. The region has unique access to markets and natural energy resources including wind, marine and geological storage. US president elect Obama has outlined a strategy for developing 5 million new green collar jobs in the US. Based on the relative sizes of the US and NI economies this would be equivalent to over 14 000 new jobs in NI if the region can deliver a similar strategy. IWEA and BWEA believe that Northern Ireland can use its strategic advantages to surpass this level.

We believe that there are four key areas in which the Northern Ireland Assembly can enable the renewable energy sector to realise climate change objectives:

1. Northern Ireland should adopt a target of 42% electricity from renewable sources by 2020.

2. A strategy for investment and development in the Grid infrastructure should be developed.

3. Consistent policy and strategy should be adopted across government. In particular energy and planning policy should be aligned.

4. A roadmap for policy development should be introduced to provide greater investment confidence in all aspects of the renewable energy sector

The need for action

The Committee is right to focus its Inquiry at identifying how Northern Ireland can play its part in tackling climate change. The scientific and economic rationales for addressing human impact on climate change is well established and widely accepted.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a group containing over 2500 scientists, reported in 2007 that ‘warming of the climate is unequivocal’ and that ‘most of the observed increase in temperature is very likely (90%) due to human activity’. The findings of the IPCC are also supported by the Academies of Science of the 11 largest countries in the world, including the Royal Society of London.

The Stern Review calculated that the dangers of unabated climate change would be equivalent to at least 5% of GDP each year. However, when more recent scientific evidence is included in the models, the Review estimates that the dangers could be equivalent to 20% of GDP or more. In contrast, the costs of action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change can be limited to around 1% of global GDP each year. The central message is that reducing emissions today will make us better off in the future: one model predicts benefits of up to $2.5 trillion each year if the world shifts to a low carbon path.

The people of Northern Ireland are asking for leadership from the Assembly. A survey conducted in 2008 by Sustainable Northern Ireland for the Northern Ireland Climate Change Impacts Programme revealed that, “92% of respondents were willing to make changes to their lifestyles, especially if encouraged to do so by strong government leadership." The Committee should provide this leadership.

The industry would welcome the opportunity to make an oral presentation to the Committee Inquiry.

BWEA and IWEA broadly support the views set out by Northern Ireland Environment Link. We have re-iterated some of these points in this response, for the purpose of emphasis. If you would like to discuss these comments we would be delighted to do so.

Submission of Evidence

The comments below relate to the Terms of Reference provided by the Committee, in its call for evidence.

(a) To identify initial commitments for Northern Ireland that will ensure it plays a fair and proportionate role as part of the UK in meeting climate change targets.

The Committee on Climate Change recommended, and the UK Government has accepted that a reduction of 80% by 2050 - based on 1990 emissions levels - would be an “appropriate" UK contribution to global aims to cut emissions by 50%. The Assembly has accepted that the provisions of the UK Climate Act will be extended to Northern Ireland. However, the UK Act does not set specific emission reduction targets for the devolved administrations.

Northern Ireland’s per capita emissions of 12.83 tonnes per annum compares badly with the UK average of 10.48 tonnes, the global average of 4 tonnes and the global fair share of 1.65 tonnes.

The Executive and Assembly should urgently make commitments to introduce a Northern Ireland Climate Change Act with a legally binding regional target to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050. This is the minimum requirement that will be necessary to play our part in the global attempt to avoid dangerous climate change.

To ensure we achieve an immediate and sustained decline in Northern Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions the Executive should set an “intermediate" target for emissions in 2020, a series of legally binding 5 year “carbon budgets" and an annual carbon reduction target at an average of at least 3% per annum. Combining indicative annual milestones with the legal framework of the budget periods should offer flexibility without compromising longer term targets.

The Committee on Climate Change’s role in Northern Ireland should be enhanced to facilitate the setting and monitoring of Northern Ireland specific budgets and action plans. The Committee on Climate Change’s reports on progress and action plans should be delivered to the Assembly and responded to by the Executive.

The Committee on Climate Change should help ensure co-ordination of emissions reduction efforts across the UK. Carbon emissions in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland are closely interlinked. Therefore, provisions to enable joint achievement of emissions reduction goals should be made.

All plans, programmes and policies should be assessed (Climate Impact Assessments) to determine their contribution to or impact on achieving carbon budgets.

(b) To consider the necessary actions and a route map for each significant sector in Northern Ireland (energy, transport, agriculture and land use, business, domestic, public sector etc)

The Committee on Climate Change’s statutory duty to Northern Ireland includes:

To provide advice on the sectors of the economy in which there are particular opportunities for contributions to be made towards meeting the budgets through reductions in emissions.

The Committee on Climate Change’s first report was released in December 2008. It includes an analysis of what opportunities exist for making emission reductions in Northern Ireland. It states Northern Ireland could contribute emissions reductions of over 2MtCO2e (Million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) per year in 2020: