This briefing note was commissioned by the Committee for Employment and Learning to provide a discussion of academic research on the effect of free school meals (FSM) on educational attainment.

The paper provides a review of existing research including studies based on Jamie Oliver's "Feed Me Better" campaign, the effects of nutritional intake on children and the economic benefits of introducing healthier meals into schools.

2 Background

A number of studies have been carried out on child nutrition, spurred in part by the work of celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and the television programme "Jamie's School Dinners" highlighting the poor quality of some of the food being provided in school canteens (such as the infamous and now banned "turkey twizzler").

The programme followed Oliver as he tried to convince local councils in England and the UK Government to improve the quality and nutritional content of school meals.

Whilst Jamie Oliver did not take the most scientific of approaches during the programme, it did highlight the importance of good quality food being available in schools. The campaign resulted in a number of schools across the UK altering their canteen menus to improve food quality with moves to expand the provision and quality of school lunches across the UK and highlighted the potential importance of good nutrition at an early age.

In 2009 the Labour Government introduced the Healthy Lives, Brighter Futures strategy which launched a series of initiatives on child development[1].

The strategy paid particular attention to health including developing healthy opportunities. In terms of school meals, the strategy wanted to increase the uptake of healthy school meals via:

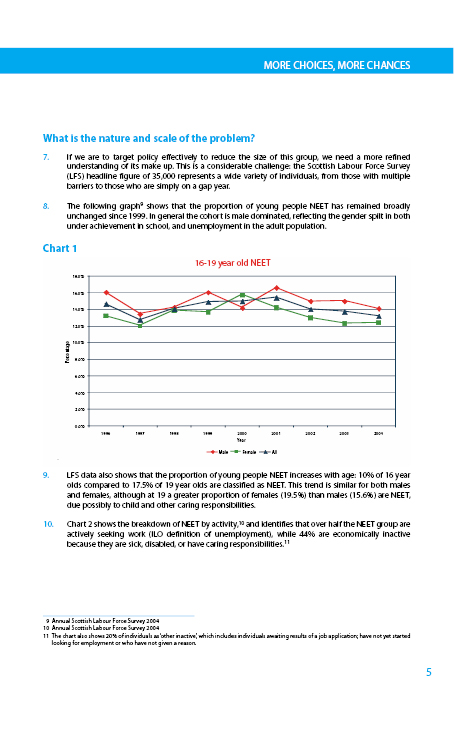

- The Department for Children, Schools and Families and the Department of Health have initiated pilots to test the health and educational outcomes expected from introducing FSM for all Primary pupils. The pilots also test extending FSM eligibility to a wider group of low income families than current rules allow;

- The pilots are to run for 2 years to July 2011. The Departments will set up a joint fund of £20 million to implement and evaluate the pilots, which will be matched by £20 million from local authorities and Primary Care Trusts (PCTs); and

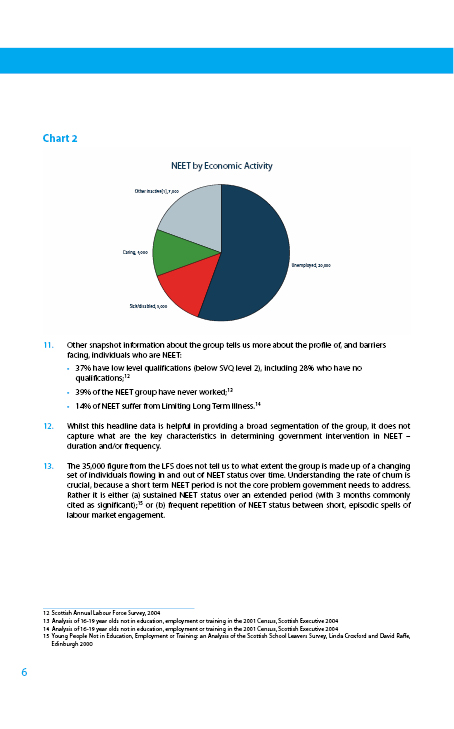

- The government stated they will consult on whether to change the law to allow those local authorities and schools that wish to develop different approaches to offering subsidised meals to do so.

- One year on from the publication of this strategy it was reported by the Department of Health that three pilots were underway on extending FSM, with more to follow. In addition there was a proposed extension to FSM eligibility which would increase the number of primary pupils able to receive FSM by 500,000. This project was expected to commence in September 2010.

3 Northern Ireland's Current FSM System

In Northern Ireland FSMs are not universally available to school pupils. Suitability is determined via means testing of the child's parent's income and whether or not they are in receipt of any benefits.

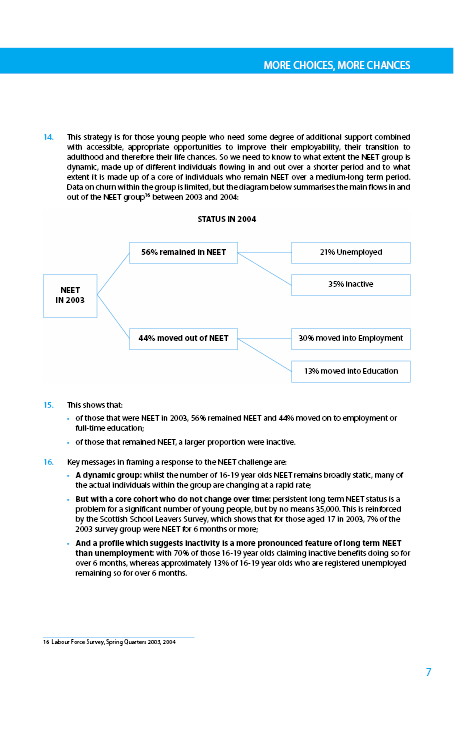

Pupils are eligible to Free School Meals if[2]:

- the parent/guardian is in receipt of Income Support, Income-Based Jobseeker's Allowance, Income-Related Employment and Support Allowance, or if a pupil claims Income Support in their own name; or,

- the parents receive the Child Tax Credit; and are ineligible for the Working Tax Credit because they work less than 16 hours per week; and have an annual taxable income of £16,190 or less; or,

- the parents receive Working Tax Credit; and have an annual taxable income of £16,190 or less and whose child/children are born on or after 2 July 2002 and attends full-time nursery school, primary school or special school; or

- he/she has a statement of special educational needs and is designated to require a special diet; or

- he/she is a boarder at a special school; or,

- he/she is the child of an asylum seeker supported by the Home Office National Asylum Support Service (NASS); and

- the parent receives the Guarantee element of State Pension Credit.

Education and Library Boards are responsible for administering the award of FSM.

The Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) developed a ten year strategy for children and young people in Northern Ireland[3]. Part of this strategy is the:

…development of a new policy framework for health promoting schools to assist schools to make effective arrangements for supporting the health and well being of pupils and staff.

In addition, the strategy intends to develop a major initiative to improve the quality of food provision in schools.

4 Scotland's Current FSM System

The Scottish Government has introduced a number of initiatives regarding school lunches, starting in 2003 with 'Hungry for Success'.

Since this programme began, a number of Acts and Regulations have been passed to promote healthy eating in schools, with the focus on getting the balance right regarding meals and encouraging pupils to make informed choices.

In Scotland free school meals can be claimed if a parent/guardian is receiving[4]:

- Income Support (IS);

- Income based Jobseekers Allowance (JSA);

- Child Tax Credit (CTC) but not Working Tax Credit and your income is less than £16,190 (with effect from April 6 2010); and

- Both maximum child tax credit and minimum working tax credit and your income is below £6,420 (with effect from April 6 2010).

Legislation was passed in November 2008 to enable local authorities to provide free school lunches to all Primary 1 to 3 pupils from August 2010. However, as a result of the increased strain on the public sector caused by the financial crisis this will be phased in, with schools that are in the 20 per cent most deprived communities in a Council area being targeted as a priority. Councils will subsequently work towards providing a nutritious free meal to all children in Primaries 1 to 3.

Discussions with Scottish civil servants found that regulations regarding the food and drink provided in Primary Schools were only introduced in 2008 and for Secondary Schools in 2009. As such no studies have yet been carried out by the Scottish government on the effect these guidelines have had on children's educational attainment or eating habits.

5 England and Wales Current FSM System

In England and Wales, as with the other regions, parents do not have to pay for school lunches if they receive any of the following:

- Income Support;

- income-based Jobseeker's Allowance;

- income-related Employment and Support Allowance;

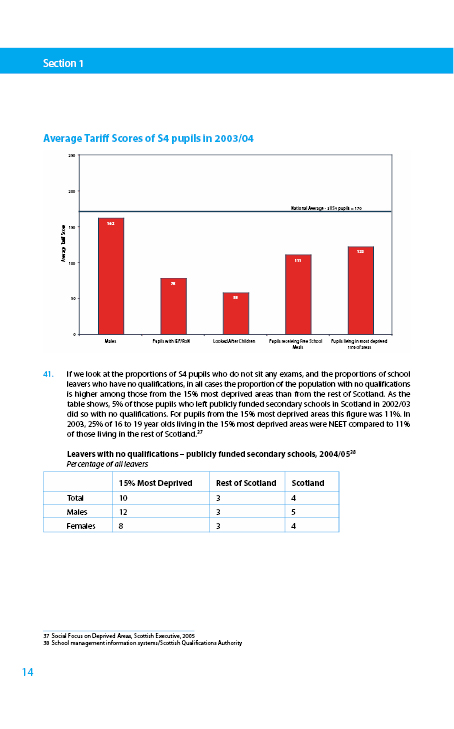

- support under Part VI of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999;

- the Guarantee element of State Pension Credit;

- Child Tax Credit, provided they are not entitled to Working Tax Credit and have an annual income (as assessed by HM Revenue & Customs) that does not exceed £16,190; or

- Working Tax Credit during the four-week period immediately after their employment finishes or after they start to work less than 16 hours per week.

Children who receive any of the qualifying benefits listed above in their own right are also eligible to receive free school meals.

The School Food Trust carried out a review of school meal take up in England for the year 2009 – 2010[5].

It found that the take up of school meals rose by 2.1 per cent from 39.3% in 2008 – 09 to 41.4% in 2009 – 10 for Primary Schools. In real terms, the number of pupils taking school lunches rose by 321,000 with just under half of this increase receiving FSM.

Reasons cited by LAs for the increase include:

- School policy on food;

- Marketing of meals to pupils, parents and head teachers (in the Primary sector);

- Increased eligibility and take up of FSM;

- Stay on site policies in Secondary Schools;

- Static and better attitudes to healthier meals; and

- Positive support (or a neutral attitude) to the provision of school meals on behalf of head teachers, governors and local councillors.

As stated in the report:

This represents a substantial change since the Jamie Oliver broadcasts in 2005, and a growing awareness that the quality of school food has improved dramatically.

The study identified issues still needing to be addressed within the sector:

- Poor kitchen and dining facilities;

- Reluctance by some pupils, parents and head teachers to engage with the healthy eating agenda;

- The need for longer lunchtimes balanced with the needs for physical activity; and

- The wider environment around schools.

- The study sums up by stating:

It will require further research outside the scope of this survey to evaluate the impact of healthier eating at school on the health, well-being, behaviour and attainment of children in England.

- It must be noted that following the recent change in the UK Government, Education Minister Michael Gove has announced plans to axe free school meals for half a million primary school children from low income families[6] in England.

6 Studies on School Meals and Nutritional Content

One of the larger studies conducted on the impact of school meals on academic achievement was completed in 2006 by the Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits for Learning[7]. The review asked two main research questions:

- How does nutrition impact upon health outcomes in children?; and

- How can the health outcomes that manifest as a result of nutrition impact upon school life experiences and outcomes?

To answer these questions the study's authors carried out an extensive literature review. The literature review examined research that looked at areas such as nutrition, socio-economic background of parents, breastfeeding and other variables which may have an impact on a child's academic achievement.

The study made a number of key findings:

- There is a complex interrelationship between nutrition, health, education, social and economic factors;

- Nutritional deficiencies prior to school entry have the potential to impact upon cognition outcomes in school age and adolescent children;

- Children with nutritional deficiencies are susceptible to moment to moment metabolic changes that impact upon cognitive ability and performance of the brain. Treatment with nutritional supplements can result in improved performance;

- Maintaining adequate levels of glucose throughout the day contributes to optimising cognition, suggesting nutritional intake should be designed to sustain an adequate level of glucose and to minimise fluctuations between meals;

- Nutrition, especially in the short term, is believed to impact upon individual behaviour (for example a lack of vitamin B has a causal relationship with aggressive behaviour and personality changes in teenagers);

- The development of food preferences in children depends on a range of biological and social factors;

- Food preferences in children are largely determined outside school (i.e. via parents, advertising and marketing);

- The constraints of low income create practical barriers to healthy eating. Additional socio-economic factors reinforce the effects of deprivation; and

- Obesity has adverse health implications but there are also important social repercussions of obesity experienced in youth.

The study went on to make the following recommendations;

- It may be helpful to have curriculum developed that incorporate children's understanding of nutrition and thus be more likely to encourage change;

- There may be a need to adopt a collaborative approach between schools and parents to address children's nutritional choices;

- There is an opportunity to capitalise on initiatives such as the extended schools policy, which have created an opportunity for schools to engage with parents and local communities, to improve diets and promote healthy eating among children; and

- It may be appropriate to consider changes to the structure of the school day, to improve the maintenance of glucose levels and promote better cognition among students.

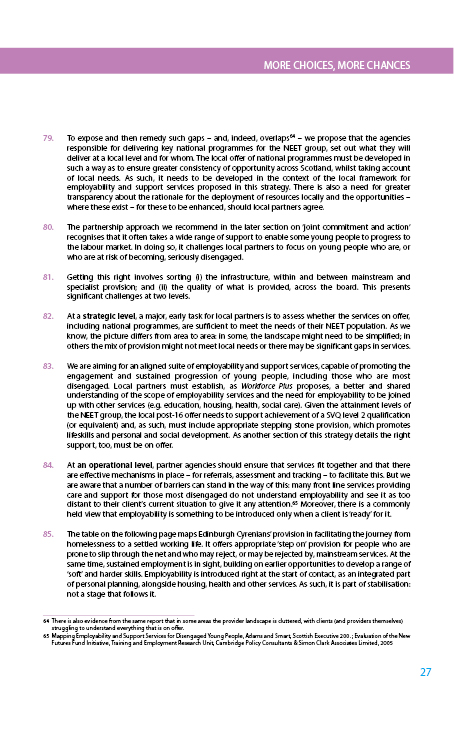

A study carried out by the University of Teesside and the Food Standards Agency in 2006 involved a review of research on the effect of nutrition and dietary change on learning, education and performance of children[8].

The study was unable to draw any firm conclusions as a result of the variety of research methods used and inconclusive results, stating that:

The findings from this report suggest that currently there is not enough evidence to show that diet / nutrition effects education, learning and performance of school aged children. This report is important, as it will inform policy makers and practitioners of the need to carry out more research (particularly within the UK) before any decisions can be made with regard to the role of nutrition in education.

In addition, a number of the studies reviewed failed to take account of factors such as socio-economic background, poverty rates of individual maturation and neurodevelopment, all of which have implications on cognition[9].

The School Food Trust carried out an overview of research in the UK on the link between child nutrition and health. The review identified and summarised recent and ongoing research relevant to the remit of the Trust[10].

It reached conclusions in three areas:

- Diet and food choice;

- School based research and school food; and

- Food related research associated with health and cognitive function.

In terms of results relevant to this paper, the review found that:

- There is limited evidence to conclude that the introduction of breakfast clubs has a positive influence on nutrient intake, behaviour or academic attainment; and

- More research is needed to provide evidence of the relationship between a healthy diet and subsequent physical and mental well being. Developing collaborative research programmes and working with partners will strengthen messages about the need for healthy eating and tackling obesity.

The review concludes by stating:

Limited research activities investigating the impact of diet and nutrition on health, behaviour and academic achievement highlights the need for continuing research activities to build a robust evidence base that supports the case for change.

7 Studies on School Meals and Academic Achievement and Behaviour

Studies on academic achievement and behaviour in school are relatively limited, with the focus generally around health outcomes rather than educational. However, a few studies do focus on this area.

A study by Feinstein et al[11] in 2008 tested the impact of diet at several points in childhood on children's school attainment. The study, using longitudinal data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)[12], examined differences between children who used packed lunches and those who ate school meals. It also took into consideration children's diet before they started school.

The study used three measures of attainment:

- School entry assessments at ages 4-5;

- Key Stage 1 tests at ages 6-7; and

- Key Stage 2 tests at ages 10-11.

Diet and achievement are influenced by a number of socioeconomic, demographic and lifestyle factors. In order to ensure these did not influence the outcome of the study, controls were applied in order to remove any confounding bias.

The study found that a child who eats a higher level of junk food at age 3 than their peers are associated with lower test scores at Key Stage 2. For children with a 'health conscious diet' it was found that they had higher test scores at Key Stage 2.

However:

Although there was a negative association between early 'junk food' consumption and later attainment scores, the estimated effect was small, suggesting that nutrition may have a diminishing role in attainment as children grow older…This may indicate a developmental period or stage where children are more susceptible to the long term cognitive impact of poor nutrition.

Feinstein et al identified policy implications for the study, stating that it:

…highlights the importance of diet before entry into formal education for later school attainment and calls for a concerted effort between schools, families, government departments and other agencies to improve the nutritional intake of children.

The School Food Trust is a non-departmental public body created by the Department for Education and Skills in 2005 to promote the education and health of children and young people by improving the quality of food supplied and consumed in schools.

It has carried out a study on school lunches to determine if the introduction of healthier food has a positive impact on learning behaviour in primary schools[13].

The study involved six primary schools over a twelve week period with four intervention schools and two control schools.

The four intervention schools had a variety of food interventions, such as new menus compliant with food based standards, health eating workshops and providing better marketing materials (such as menus with pictures of the meals). The schools also had changes made to the dining environment such as alterations to the layout, the queuing system and the redecorating of the dining room.

In order to test changes to pupil behaviour, students were initially observed prior to the beginning of the 12 week period to establish a baseline and again at the end of the intervention.

Behaviour was observed in three ways:

- Pupil-teacher interaction;

- Pupil-pupil interaction; and

- Working alone.

- Behaviour was determined as either on-task (pupils level of concentration) or off-task (pupils were disengaged and/or disruptive). They study found that following the intervention, pupils were 3.4 times more likely to be on task in pupil-teacher interaction compared with pupils from the control schools. Conversely, pupils from the intervention schools were 2.3 times more likely to be off task in pupil-pupil interactions than in the control schools.

- The study concluded that:

This study provides some objective evidence that an intervention in primary schools to improve school food and the dining environment has a positive impact on pupils' alertness and their ability to learn in the classroom after lunch. However, if this raised alertness is not appropriately channelled and supervised, it may result in increased off-task behaviour when pupils are asked to work together.

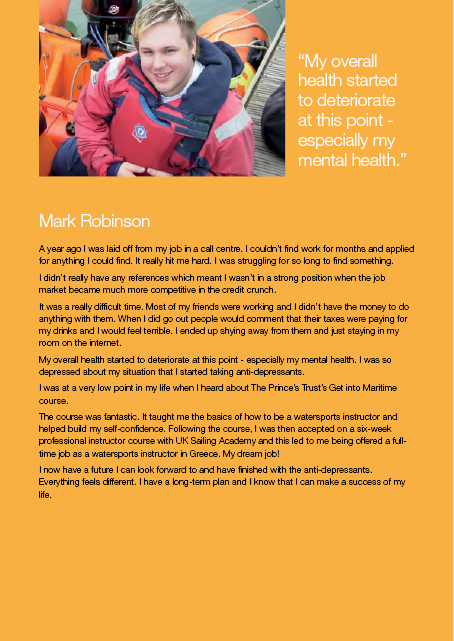

A recent study by Belot and James (2009)[14] used the "Jamie Oliver Feed Me Better" campaign as its source material. As the campaign focused on a specific area (the Greenwich Borough in London, England) it was possible to conduct a before and after study on the pupils of schools who joined the project.

The study used pupil and school level data from the National Pupil Database and School Census. It subsequently compares educational outcomes (at Keystage 2, which has three main components – English, Maths and Sciences) before and after the reform with neighbouring Local Educational Authorities (LEAs) acting as control groups.

Belot and James investigated three outcome variables:

- Educational Outcomes;

- Take-up Rates; and

- Sickness Absenteeism.

- The study found that Key Stage 2 results were significantly improved after the introduction of the improved school meals, with results in English and Science most effected. For English, between 3 and 6% more pupils scored level 4 and between 3 and 8% more pupils gaining level 5 in Science.

- Belot and James concluded that there was no evidence that the campaign helped children who take Free School Meals, with the authors suggesting that it is FSM pupils who would find the change in menu most difficult as:

…these pupils were probably eating the "unhealthy" meals on a daily basis and would therefore maybe the most put off by the change in menus.

In terms of take up rates of FSM, the study found no change.

Absenteeism is divided into authorised and unauthorised absences. Authorised absences are those that are formally pre-arranged with the school and are mostly linked to sickness. The study found that authorised absences dropped by 0.8% which may not seem a significant figure but equates to 15% of the average rate of absenteeism. There was no apparent effect on unauthorised absences.

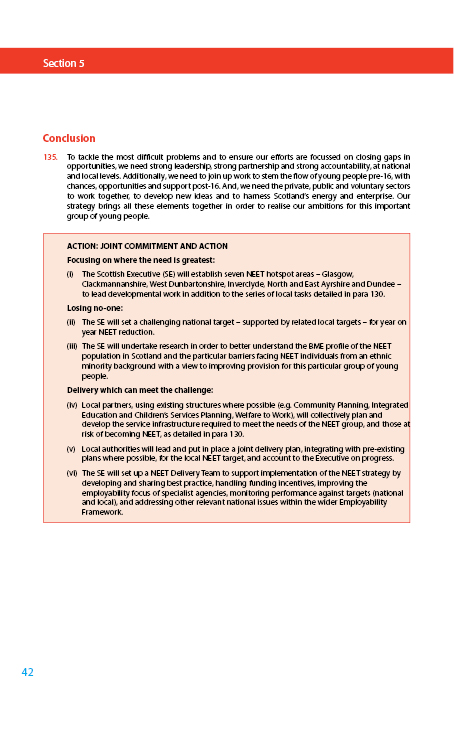

The study also examined the costs and benefits of the project for the schools themselves. By September 2007, 28,000 children from the county benefited from the programme, at a cost of £1.2 million for the council (£43 per child). The majority of these costs were one off and capital based, such as new kitchens and equipment, as many of the schools were simply not outfitted for cooking food from scratch.

Whilst assessing the economic benefits of healthy school lunches, Belot and James used a similar process to that used by Machin and McNally (2008) for their analysis of the benefits of the Literacy Hour introduced to schools in the 1990s. Machin and McNally calculated the overall benefit of the programme in terms of future labour market earnings using the British Cohort Study, that includes wages at age 30 and reading age at 10. Machin and McNally estimated the benefit of literacy hour to be between £75.40 and £196.32 per annum per child, adding up to a lifetime benefit of between £2,103 and £5,476.

Belot and James state that:

The effects we have identified are comparable in magnitude to those estimates by Machin and McNall.

8 Studies on School Meals and Economic Benefit

It is important to consider the economic implications of nutritious school meals and academic achievement. As seen above in the Belot and James study, it can be suggested that pupils that achieve better through primary and secondary school will provide additional benefit to the economy.

A study by Shemil et al[15] evaluated school breakfast clubs and identified three areas where the introduction of clubs could have an economic impact:

- Individual (children, parents, school based staff);

- Institutional (school, family, service provider); and

- More widely (government, employers, etc).

The study examined four lines of enquiry:

- Description of financial structures and costs;

- Description of resource inputs and estimation of associated costs;

- Estimation of cost consequences that may result from the effects of clubs on schools, children, their families and communities; and

- An analysis of relationships between the net costs of implementing and maintaining the clubs and observed benefits of the clubs.

Qualitative data gathered from the study found that participants frequently suggested that improvements in attendance, punctuality, behaviour and concentration were attributable to the presence of a club and had improved the marginal efficiency of resources allocated to teaching and learning.

In addition, several parents who were questioned as part of the study stated that where breakfast was provided for free at school there was a reduction in household food costs, which could make a considerable financial contribution for the family. Other benefits include a reduction in childcare costs and increased opportunities for parents to work or study.

- The study's authors stated:

This factor would not only impact directly at the level of the family economy, but would also, from a societal perspective, precipitate changes in the indirect costs associated with the value of production.

However, the study concluded that:

The costs of a school breakfast club appears to be associated with some weak benefits (as well as some unmeasured societal benefits linked to employment and family economy) but it is not possible to conclude whether or not this initiative was the best way to use the available funding.

9 Summary

Consideration of the studies discussed in this paper has highlighted a number of key points:

- Nutrition has an effect on academic achievement and behaviour in children, however, the extent and duration of this effect is still unclear, although one study found an improvement in Key Stage test results following the Jamie Oliver Feed Me Better Campaign was introduced to schools in England;

- Junk food can have a negative impact on learning for children aged 3;

- Diet before entry into formal education has an impact on later school attainment;

- Interventions to improve school food and the dining environment can have a positive impact on pupils alertness, behaviour and their ability in the classroom; and

- There may be potentially significant long term economic benefits from improving the nutrition of school meals.

Whilst there is a body of evidence surrounding the effect of healthy school meals on children, it must be noted that a number of studies highlighted the need for more research in this area. Importantly, with regional governments rolling out FSM to more schools and greater numbers of children, the opportunity for research into its effects is improving, although these studies will by the nature of the topic being examined, necessitate longitudinal studies.

[1] Department of Health and the Department for children, schools and families, Healthy Lives, brighter futures: The strategy for children and young people's health http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_094397.pdf (first accessed 16th July 2010)

[2] Education Support for Northern Ireland Benefits, Free School Meals http://www.education-support.org.uk/parents/benefits/free-school-meals (first accessed 27th July 2010)

[3] OFMDFM, 2006, Our Children and Young People – our pledge: A ten year strategy for children and young people in Northern Ireland 2006 - 2016

[4] Scottish Government, School Lunches, www.scotland.gov.uk/topics/Education/Schools/HLivi/schoolmeals

[5] School Food Trust, Nelson et al July 2010, School Lunch take up in England 2009 – 2010

[6] The Guardian 22nd June 2010 Free school meals: Health professionals join the backlash over cuts http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2010/jun/22/free-school-meals-health-backlash-cuts (first accessed 21st July 2010)

[7] Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits for Learning June 2006 Sorhaindo, A and Feintstein, L What is the Relationship Between Child Nutrition and School Outcomes

[8] University of Teesside and Food Standards Agency, April 2006 A systematic review of the effect of nutrition, diet and dietary change on learning, education and performance of children of relevance to UK schools http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/systemreview.pdf (First accessed 19th July 2010)

[9] Please note, the University of Teeside review was carried out on research conducted mainly in the USA and all papers discussed were pre 2006. Of the 29 papers considered in detail, 15 were on breakfast, 6 on sugar and ADHD, 5 on fish oil and 2 considered vitamin supplements. The final study examined good diet but was dropped due to poor quality.

[10] School Food Trust The Link Between Child Nutrition and Health: An Overview of Research in the UK

[11] Journal of Epidemiol Community Health 2008 Feinstein et al Dietary Patterns Related to Attainment in School: The Importance of Early Eating Patterns

[12] ALSPAC is an ongoing population based study designed to investigate the effects of environment, genetics and other influences on the health and development of children and has 13,988 participants born between 1 April 1999 and 31 December 1992.

[13] School Food Trust School Lunch and Learning Behaviour in Primary Schools: An Intervention Study www.schoolfoodtrust.org.uk/download/.../sft_slab1_behavioural_findings.pdf (first accessed 23rd July 2010)

[14]Institute for Social and Economic Research, January 2009, Belot, M and James, J Healthy School Meals and Educational Outcomes http://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/files/iser_working_papers/2009-01.pdf (first accessed 23rd July 2010)

[15] Childcare, Health and Development, September 2004 Shemil et al A National Evaluation of School Breakfast Clubs: Where Does Economics Fit in?

Northern Ireland Adviser on Employment and Skills

Department of Education

Committee for Employment and Learning

Room 283,

Parliament Buildings,

Stormont,

Ballymiscaw,

Belfast BT4 3XX

Telephone: (028) 9052 0379

Fax: (028) 9052 1433

E-mail: cel@niassembly.gov.uk

Caitriona Ruane MLA

Minister of Education

Department of Education

Rathgael House

Balloo Road

Bangor

BT19 7PR 2nd July 2010

Dear Caitriona,

Re: Bus passes for students who undertake study at more than one school

As you are aware, the Committee for Employment and Learning is currently undertaking an Inquiry into young people (16-24) who are not in education, employment or training (NEET). The Committee wanted to ensure that Members heard the views of rural people and decided it would be useful to ask the principal of a rural school what methods are available to attempt to ensure that pupils are less likely to find themselves NEET. Mr Errol McMaster, Principal of Glastry College on the Ards peninsula recently briefed the Committee on this issue.

The Committee was impressed by much of what Mr McMaster said about the issue of young people who are NEET. Members were particularly interested in the collaboration between Mr McMaster's school and other schools in the area under the North Down and Ards Collaborative Group. This group, amongst other things, allows schools to band together to provide a wider range of subject choices to pupils, particularly at A Level. Mr McMaster indicated a range of benefits provided by this collaborative approach and the Committee believes that it is a useful way to increase choices for young people in rural (and urban) areas which may contribute towards ensuring that they remain engaged in full-time education or training.

Mr McMaster indicated that the difficulty with this collaboration is bus passes. The Committee understands that currently students' bus passes will take them from their home bus stop to the school or college at which they are registered, but not to other schools or colleges where they may be studying and starting their day. The passes really only apply to a single route. Mr McMaster highlighted that this has caused significant problems. I understand that Mr McMaster and colleagues at St. Columbanus College in Bangor have already flagged this issue up to your officials and those of the SEELB.

The Committee agreed that I should write to you to ask you to examine this issue. It would seem that there should be a straightforward and practical solution to this issue.

I will be writing in similar terms to the Regional Development Minister as transport sits within his remit.

Yours sincerely,

Dolores Kelly MLA

Chairperson

Committee for Employment and Learning

Room 283,

Parliament Buildings,

Stormont, Ballymiscaw,

Belfast BT4 3XX

Telephone: (028) 9052 0379

Fax: (028) 9052 1433

E-mail: cel@niassembly.gov.uk

Dolores Kelly MLA, Chairperson

Committee for Employment and Learning

Caitríona Ruane MLA

Minister of Education

Department of Education

Rathgael House, Balloo Road, Bangor

BT19 7PR 10th September 2010

Dear Caitríona,

Re: Bus passes for students who undertake study at more than one school

Many thanks for your response of 25th August with regard to the above. The Committee considered your response at its meeting on 8th September and agreed that I should write to you again to seek greater clarification.

In your response you indicate that it would be "…both difficult and costly…" to make changes to the bussing system even if the change was just for the buses to and from schools at the beginning and end of the day. The Committee would be interested to know if any analysis of the costs involved in making the pupils' bus passes more flexible at the beginning and end of the day has actually been undertaken and, if so, what level of increased cost is involved.

The evidence submitted to the Committee thusfar, with respect to its Inquiry into young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET), is very supportive of Area Learning Community (ALC) concept, which you mention in your response. The ALCs are a positive and progressive innovation and the Committee has firsthand experience of this model working very well in other jurisdictions to help combat the rise in the number of young people who are NEET and increase the options open to them. The Committee would be keen to hear more about your ideas around using the ALCs to resolve transport issues and issues surrounding the broadening of the curriculum.

The Committee is very supportive of this mode of working and looks forward to sharing the findings of its Inquiry with you. Members are committed to working in co-operation with other Committees and Executive Departments on the NEETs issue and greatly appreciate your assistance in achieving this end.

Yours sincerely,

Dolores Kelly MLA

Chairperson

Fastrack to IT Northern Ireland

Queens University/Princes Trust/Save the Children

Childhood in Transition

EU Commission

Brussels, 15.9.2010

COM(2010) 477 final

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions

Youth on the Move

An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union

{SEC(2010) 1047}

An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union

1. Introduction

The Europe 2020 Strategy sets ambitious objectives for smart, inclusive and sustainable growth. Young people are essential to achieve this. Quality education and training, successful labour market integration and more mobility of young people are key to unleashing all young people's potential and achieving the Europe 2020 objectives.

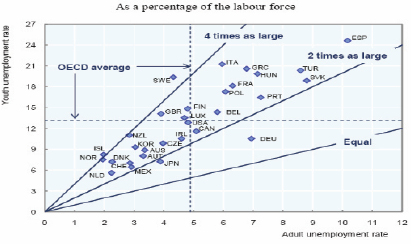

Europe's future prosperity depends on its young people. There are close to 100 million in the EU, representing a fifth of its total population[1]. Despite the unprecedented opportunities which modern Europe offers, young people face challenges – aggravated by the economic crisis - in education and training systems and in accessing the labour market. Youth unemployment is unacceptably high at almost 21%[2]. In order to reach the 75% employment target for the population aged 20-64 years, the transition of young people to the labour market needs to be radically improved.

By 2020, it is estimated that 35% of all jobs will require high-level qualifications, combined with a capacity to adapt and innovate, compared to 29% today. This means 15 million more jobs requiring high-level qualifications[3]. An increasing number of jobs require e-skills, but the EU economy is hampered by a shortage of highly qualified ICT practitioners[4]. Fewer than one person in three in the EU (31.1%[5]) has a higher education degree compared to over 40% in the US and over 50% in Japan. The EU has a lower share of researchers in the labour force than its competitors[6]. The Europe 2020 Strategy has agreed the EU headline target that by 2020, at least 40% of 30-34 years olds should have completed tertiary or equivalent education.

Too many young people leave school early, increasing their risk of becoming unemployed or inactive, living in poverty and causing high economic and social costs. Currently, 14.4% of 18-24 years old in the EU have less than upper secondary education and are not in further education and training[7]. The EU benchmark is to reduce early school-leaving to 10%. Europe also has to do better on literacy – 24.1% of 15-year olds are low performers in reading literacy and this share has increased in recent years[8].

The implementation of national strategies for lifelong learning remains a challenge for many Member States, including developing more flexible learning pathways to allow people to move between different education levels and attract non-traditional learners.

1.1. Focus of the initiative

Youth on the Move is the EU's flagship initiative to respond to the challenges young people face and to help them succeed in the knowledge economy. It is a framework agenda announcing key new actions, reinforcing existing activities and ensuring the implementation of others at EU and national levels, while respecting the subsidiarity principle. Candidate countries should also be able to benefit from this initiative, through the appropriate mechanisms. It will harness the financial support of the relevant EU programmes on education, youth, and learning mobility, as well as the Structural Funds. All existing programmes will be reviewed to develop a more integrated approach to support the Youth on the Move initiative under the next Financial Framework. Youth on the Move will be implemented in close synergy with the "Agenda for New Skills and Jobs" flagship initiative, announced in Europe 2020.

Youth on the Move will focus on four main lines of action:

- Smart and inclusive growth depends on actions throughout the lifelong learning system, to develop key competences and quality learning outcomes, in line with labour market needs. Europe needs to extend and broaden learning opportunities for young people as a whole, including supporting the acquisition of skills through non-formal educational activities. Youth on the Move will support these actions, inter alia, by proposing a Council Recommendation to encourage Member States to tackle the high level of early school leaving, through the 2011 European Year of Volunteering and with a Council Recommendation on the validation of non-formal and informal learning. The Commission is also promoting apprenticeship-type vocational training and high quality traineeships as workplace learning experiences, building bridges to the labour market.

- Europe needs to raise the percentage of young people participating in higher education or equivalent to keep up with competitors in the knowledge-based economy and to foster innovation. It also needs to make European higher education more attractive and open to the rest of the world and to the challenges of globalisation, notably by promoting student and researcher mobility. Youth on the Move will seek to improve the quality, attractiveness and responsiveness of higher education and promote more and better mobility and employability, inter alia by proposing a new agenda for the reform and modernisation of higher education, including an initiative on benchmarking university performance and a new EU international strategy to promote the attractiveness of European higher education and to foster academic cooperation and exchanges with world partners.

- The EU's support for learning mobility through programmes and initiatives will be reviewed, expanded and linked up with national and regional resources. The international dimension will be reinforced. Youth on the Move will support the aspiration that by 2020 all young people in Europe should have the possibility to spend a part of their educational pathway abroad, including via workplace-based training. A Council Recommendation aimed at removing obstacles to mobility is proposed as part of the Youth on the Move package, accompanied by a 'Mobility Scoreboard' to measure Member States' progress in this regard. A dedicated website on Youth on the Move giving access to information on EU mobility and learning opportunities[9] will be set up and the Commission will propose a Youth on the Move card to facilitate mobility. The new intra-EU initiative "Your first EURES Job" will support young people to access employment opportunities and take up a job abroad, as well as encouraging employers to create job openings for young mobile workers. The Commission will also consider transforming the preparatory action "Erasmus for young entrepreneurs" into a programme to promote entrepreneurs' mobility.

- Europe must urgently improve the employment situation of young people. Youth on the Move presents a framework of policy priorities for action at national and EU level to reduce youth unemployment by facilitating the transition from school to work and reducing labour market segmentation. Particular focus is put on the role of Public Employment Services, encouraging a Youth Guarantee to ensure all young people are in a job, in education or in activation, creating a European Vacancy Monitor and supporting young entrepreneurs.

2. Developing Modern Education and Training Systems to Deliver Key Competences and Excellence

There is a need for better targeted, sustained and enhanced levels of investment in education and training to achieve high quality education and training, lifelong learning and skills development. The Commission encourages Member States to consolidate and, where necessary, expand investment, combined with strong efforts to ensure the best returns to public resources. In a climate of pressure on public funds, diversification of funding sources is also important.

In order to reduce early school leaving to 10%, as agreed under the EU 2020 Strategy, action should be taken early, focused on prevention and targeting pupils identified as being at risk of dropping-out. The Commission will propose a Council Recommendation to reinforce Member State action to reduce school drop-out rates. The Commission will also establish a High-Level expert Group to make recommendations on improving literacy and will present a Communication to strengthen early childhood education and care.

Young people are confronted with an increasing number of educational choices. They need to be enabled to take informed decisions. They need to get information about education and training paths, including a clear picture of job opportunities, to lay the basis for managing their career. Quality career guidance services and vocational orientation need to be further developed, with strong involvement of labour market institutions, supported by actions to improve the image of sectors and professions with employment potential.

High quality learning and teaching should be promoted at all levels of the education system. Key competences for the knowledge economy and society, such as learning to learn, communication in foreign languages, entrepreneurial skills and the ability to fully exploit the potential of ICT, e-learning and numeracy[10], have become ever more important[11]. The Commission will present a Communication on competences supporting lifelong learning in 2011, including proposals to develop a common language between the world of education and the world of work[12].

The demand for qualifications is being driven upwards, including in low-skilled occupations. Projections foresee that around 50% of all jobs in 2020 will continue to depend on ediumlevel qualifications provided through vocational education and training (VET). The Commission has underlined in its 2010 Communication on European cooperation in VET[13] that it is vital for this sector to modernise. Priorities include ensuring that pathways and permeability between VET and higher education are facilitated, including through the development of national qualifications frameworks, and maintaining close partnerships with the business sector.

Early workplace experience is essential for young people to develop the skills and competences required at work[14]. Learning at the workplace in apprenticeship-type training is a powerful tool for integrating young people gradually into the labour market. The provision and quality of apprenticeship-type training greatly varies among Member States. Some countries have recently started to set up such training schemes. The involvement of Social Partners in their design, organisation, delivery and funding is important for their efficiency and labour market relevance. These actions should be further pursued in order to increase the skills base in vocational pathways, so that by the end of 2012 at least 5 million young people in Europe should be able to enrol in apprenticeship training (currently, the figure is estimated to be 4.2 million[15]).

Acquiring initial work experience through traineeships has gained importance for young people in recent years, allowing them to adjust to labour market demands. Some Member States have also set up work experience schemes in response to reduced job openings for young people. These schemes should be accessible to all, of high quality and with clear learning objectives and should not substitute regular jobs and probation periods.

Unemployment among graduates from different levels of education and training is increasingly a cause for concern. European systems have been slow to respond to the requirements of the knowledge society, failing to adapt curricula and programmes to the changing needs of the labour market. The Commission will propose an EU benchmark on employability in 2010 in response to the Council request of May 2009.

Youth on the Move should also aim to expand career and life-enhancing learning opportunities for young people with fewer opportunities and/or at risk of social exclusion. In particular, these young people should benefit from the expansion of opportunities for nonformal and informal learning and from strengthened provisions for the recognition and validation of such learning within national qualifications frameworks. This can help to open the doors to further learning on their part. The Commission will propose a Council Recommendation to facilitate the validation of this type of learning[16].

Key new actions:

- Propose a draft Council Recommendation on reducing Early School leaving (2010): The Recommendation will set out a framework of effective policy responses related to the different causes of high school drop-out rates. It will focus on pre-emptive, preventive as well as remedial measures.

- Launch a High Level Expert Group on Literacy (2010) to identify effective practice in Member States to improve reading literacy among pupils and adults and formulate appropriate recommendations.

- Raise the attractiveness, provision and quality of VET as an important contribution to the employability of young people and the reduction of early school leaving: The Commission, together with Member States and the social partners, will re-launch cooperation in the area of VET, at the end of 2010, and propose measures at national and European level.

- Propose a quality framework for traineeships, including addressing the legal and administrative obstacles to transnational placements. Support better access and participation in high quality traineeships, including by stimulating companies to offer traineeship places and be good host enterprises (e.g. through quality labels or awards), as well as through Social Partner arrangements and as part of a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policy.

- Propose a draft Council Recommendation on the promotion and validation of non-formal and informal learning (2011) to step up Member State action to promote recognition of skills acquired through these learning activities.

3. Promoting the Attractiveness of Higher Education for The Knowledge Economy

Higher education is a major driver of economic competitiveness in the knowledge-driven economy, making high quality third-level education essential in achieving economic and social objectives. With an increasing number of jobs requiring high-level skills, more young people will need to enter and complete higher education in order for the EU to reach the Europe 2020 target of 40% attainment of higher education or equivalent. In addition, research should attract and retain more young people by providing attractive employment conditions. Realising these objectives will require a multi-faceted approach, aiming at modernising higher education, ensuring quality, excellence and transparency and stimulating partnerships in a globalised world.

Some European universities are amongst the best in the world, but are hampered in realising their full potential. Higher education has suffered a long period of under-investment, alongside major expansion in student numbers. The Commission reiterates that for a modern and well-performing university system, a total investment of 2% of GDP (public and private funding combined), is the minimum required for knowledge-intensive economies.[17] Universities should be empowered to diversify their income and take greater responsibility for their long-term financial sustainability. Member States need to step up efforts to modernise higher education[18] in the areas of curricula, governance and funding, by implementing the priorities agreed in the context of the Bologna process, supporting a new agenda for cooperation and reform at EU level and focusing on the new challenges in the context of the Europe 2020 Strategy.

Maintaining a high level of quality is crucial for the attractiveness of higher education. Quality assurance in higher education needs to be reinforced at European level, by supporting cooperation among stakeholders and institutions. The Commission will monitor progress and set out priorities in this field in a report to be adopted in 2012, in response to a Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council[19].

In a more global and mobile world, transparency regarding performance of higher education institutions can stimulate both competition and cooperation and be an incentive for further improvements and modernisation. However, existing international rankings can give an incomplete picture of the performance of universities, over-emphasising research, while excluding other key factors that make universities successful, such as teaching quality, innovation, regional involvement and internationalisation. The Commission will present in 2011 the results of a feasibility study to develop an alternative multi-dimensional global university ranking system, which takes into account the diversity of higher education institutions.

Europe's innovation capacity will require knowledge partnerships and stronger links between education, research and innovation (the 'knowledge triangle'). This includes fully exploiting the role of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) and the Marie Curie Actions, while drawing out the lessons learned in both. In this context, the Commission will reinforce and extend the activities of the European platform for dialogue between universities and business (EU Forum for University Business Dialogue), with a view to increasing the employability of students and to developing the role of education in the 'knowledge triangle'.

Higher education is becoming increasingly internationalised. More mobility, international openness and transparency are needed to attract the best students, teachers and researchers, to create and reinforce partnerships and academic cooperation with universities from other parts of the world. This will require a specific emphasis on reinforcing international cooperation, programmes and policy dialogue in higher education. A Communication setting out the key challenges and actions needed for higher education in Europe in a 2020 perspective will be presented in 2011, including an EU internationalisation strategy[20].

Key new actions:

- Support the reform and modernisation of higher education, by presenting a Communication (2011), which will set out a new reinforced agenda for higher education: This will focus on strengthening the employability of graduates, encouraging mobility, including between academia and industry, promoting transparent and high quality information on study and research possibilities and the performance of institutions. It will also focus on opening up opportunities to non-traditional learners and facilitating access for disadvantaged groups, including through adequate financing. The reinforced agenda will also propose an EU internationalisation strategy, promoting the attractiveness of European higher education.

- Benchmark higher education performance and educational outcomes: The Commission will present the results of a feasibility study in 2011, to develop a multi-dimensional global university ranking system, taking into account the diversity of higher education institutions.

- Propose a multiannual Strategic Innovation Agenda (2011), defining the role of the EIT in Europe's multi-polar innovation context and laying down priorities for higher education, research, innovation and entrepreneurship over the next seven years.

4. Supporting A Strong Development of Transnational Learning and Employment Mobility for Young People

While mobility among the overall population in the EU is not particularly high, studying and working abroad is particularly attractive for young people. The majority of 'mobile' people in the EU are between 25 and 34 years old. This age group tends to have better knowledge of languages and fewer family obligations. Increased mobility is also due to increasingly open borders and more comparable education systems. This trend should be supported by providing young people with access to more opportunities for enhancing skills or finding a job.

4.1. Promoting learning mobility

Learning mobility is an important way in which young people can strengthen their future employability and acquire new professional competences, while enhancing their development as active citizens. It helps them to access new knowledge and develop new linguistic and intercultural competences. Europeans who are mobile as young learners are more likely to be mobile as workers later in life. Employers recognise and value these benefits. Learning mobility has also played an important role in making education and training systems and institutions more open, more European and international, more accessible and more efficient[21]. The EU has a long and successful track record of supporting learning mobility through various programmes and initiatives, of which the best known is the Erasmus programme[22]. Future schemes, such as the creation of the European Voluntary Humanitarian Aid Corps foreseen by the Lisbon Treaty, could also contribute to this process. Some Member States also use the Structural Funds, particularly the European Social Fund, for transnational learning and job mobility. Mobility and exchanges of higher education staff and students between European and extra-European universities is supported under the Erasmus Mundus and Tempus programmes.

The Commission's aim is to extend opportunities for learning mobility to all young people in Europe by 2020 by mobilising resources and removing obstacles to pursuing a learning experience abroad[23].

The Green paper on Learning Mobility (July 2009)[24] launched a public consultation on how best to tackle obstacles to mobility and open up more opportunities for learning abroad. This led to over 3,000 responses, including from national and regional Governments and other stakeholders[25]. These show a widespread wish to boost learning mobility in all parts of the education system (higher education, schools, vocational education and training), but also in non-formal and informal learning settings, such as volunteering. At the same time, the responses confirm that many obstacles to mobility remain. Therefore, in conjunction with this Communication, the Commission is proposing a Council Recommendation on Learning Mobility, as a basis for a new concerted campaign among Member States to finally remove obstacles to mobility. Monitoring of progress will be reflected in a 'Mobility Scoreboard', which will provide a comparative picture of how Member States are progressing in dismantling these barriers.

To improve understanding of the rights of students studying abroad, the Commission is publishing, alongside this Communication, guidance on relevant European Court of Justice rulings. This deals with issues such as access to educational institutions, recognition of diplomas and portability of grants, to help public authorities, stakeholders and students understand the implications of established case law.

The "Bologna" Ministers for Higher Education, representing 46 countries, set a benchmark in 2009 that at least 20% of those graduating in the European Higher Education Area should have had a study or training period abroad by 2020[26]. In response to the Council request of May 2009, the Commission will propose in 2010 EU benchmarks on learning mobility, focusing in particular on students in higher education and VET.

European instruments and tools to facilitate mobility, such as European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning (EQF) and Europass, should be fully implemented in order to provide their full benefit for mobile learners[27]. Virtual mobility, through the use of ICT and e-learning, should be promoted to complement physical mobility. The Commission will develop existing Europass elements into a European skills passport, to increase transparency and transfer of competences acquired through both formal and non-formal learning across the European Union. In this context, it will develop tools to identify and recognise competences of ICT practitioners and users, including a European Framework for ICT Professionalism in line with the EU e-skills strategy[28]. The Commission will also seek to develop a Youth on the Move card to speed up the integration process for mobile learners when moving abroad and provide other advantages in line with national youth or student cards.

EU funding supports student, researcher, youth and volunteer mobility through a number of programmes, although the number of young people who are able to benefit from these remains relatively small at around 380,000 per annum. The Commission will improve the efficiency and functioning of these programmes and promote an integrated approach to support Youth on the Move under the next Financial Framework.

Key new actions:

- Set up a dedicated Youth on the Move website for information on EU learning and mobility opportunities (2010): This website should give full transparency to all relevant EU programmes, opportunities and rights related to learning mobility for young people, and be progressively developed, e.g. linking EU actions to national and regional initiatives, providing information about funding possibilities, education and training programmes across Europe (taking account of ongoing work on transparency tools and the existing PLOTEUS portal), listing quality enterprises providing traineeships and similar.

- Propose a draft Council Recommendation on promoting the learning mobility of young people (2010), addressing obstacles to learning mobility at national, European and international level. This builds on the feedback from the 2009 public consultation on the Green Paper "Promoting the learning mobility of young people". Through regular monitoring, a "Mobility Scoreboard" will benchmark and measure progress in removing these obstacles in the Member States.

- Develop a Youth on the Move card to facilitate mobility for all young people (i.e. students, pupils, apprentices, trainees, researchers and volunteers), helping to make the integration process of mobile learners smoother.

- Publish guidance on the European Court of Justice rulings on the rights of mobile students (2010): This covers issues such as access, recognition and portability of grants.

- Propose a European Skills Passport (2011), based on existing elements of Europass, to record in a transparent and comparable way the competences acquired by people throughout their lives in a variety of learning settings, including e-skills and informal and non-formal learning. This should facilitate mobility by easing the recognition of skills across countries.

4.2. Promoting employment mobility

As underlined most recently in the Monti report[29], even in the economic downturn, jobs remain unfilled in the EU. This is partly due to a lack of labour mobility within the Union. However, a majority of Europeans (60%) think that people moving within the EU is a good thing for European integration, 50% think it is a good thing for the labour market and 47% think it is a good thing for the economy[30].

Working abroad is particularly attractive for young people. Yet there are still many obstacles that, in practice, hinder free movement: these need to be removed to make it easier for young workers to move and work within the Union and acquire new skills and competences. Young people are often willing to work abroad, but do not take up job opportunities in other countries because they are not aware of them, and because of the costs of moving. Advice and financial support to cover the relocation costs of young job applicants in the new country, as well as some of the integration costs usually borne by the employer, could contribute to better matching labour supply with labour demand, while giving young workers valuable experiences and skills.

Young labour market newcomers and businesses often do not connect easily, and Public Employment Services (PES) do not always offer services suited to young people and do not engage companies enough in recruiting young people all over Europe. EURES and the employment opportunities it offers are not fully exploited by the PES, even if 12% of Europeans know about it and 2% have actually used it[31].

Facing future labour shortages, Europe needs to retain as many highly skilled workers as possible and also attract the right skills for the expected increase in labour demands. Special efforts will be needed to attract highly skilled migrants in the global competition for talent. A wide range of aspects beyond traditional employment policy contribute to the relative attractiveness of a work location. As certain professions see too many Europeans emigrating and too few third country immigrants coming in, policies should address this. This includes raising awareness of citizens' rights when moving within the EU, in particular in the field of social security coordination and free movement of workers, simplified procedures for social security coordination taking into account new mobility patterns, reducing obstacles to free movement of workers (e.g. access to jobs in the public sector), improving information to young people about professions in demand, raising the attractiveness of jobs in professions which see brain-drain (e.g. scientific and medical professions) and identifying within the New Skills and Jobs initiative those occupations with shortages to which young talent within and outside the EU should be attracted.

Key new actions:

- Develop a new initiative: "Your first EURES job", as a pilot project (subject to it receiving the required financial support by the budgetary authority) to help young people with finding a job in any of the EU-27 Member States and moving abroad. Looking for a job abroad should be as easy as searching in one's own country: "Your first EURES job" will provide advisory, job search, recruitment and financial support to both young jobseekers willing to work abroad and companies (in particular SMEs) recruiting young European mobile workers and providing a comprehensive integration programme for the newcomer(s). This new mobility instrument should be managed by EURES, the European job mobility network of Public Employment Services.

- Create in 2010 a "European Vacancy Monitor", to show young people and employment advisers where the jobs are in Europe and which skills are needed. The European Vacancy Monitor will improve transparency and information on available jobs for young jobseekers by developing an intelligence system on labour and skills demand all over Europe.

- Monitor the application of the EU legislation on freedom of workers, to ensure that incentive measures in Member States for young workers, including in vocational training, are also accessible to mobile young workers, and identify, in 2010, areas for action to promote youth mobility with Member States in the Technical Committee on the free movement of workers.

5. A Framework for Youth Employment

While all Member States have youth employment policies in place, and many have taken additional action during the crisis - often with close involvement of the Social Partners -, much still needs to be done[32], [33]. Measures for reducing high youth unemployment and raising youth employment rates in times of tight public budgets must be efficient in the short term and sustainable in the longer term to address the challenge of demographic change. They should cover in an integrated manner the sequence of steps for young people in the transition from education into work and ensure safety nets for those who risk dropping out from education and employment. The existing EU legislation to protect young people at work must be implemented fully and adequately[34].

Evidence shows that robust policy coordination at European level within the common principles for flexicurity can make a real difference for young people. Together with stakeholders including Public Employment Services (PES), Social Partners, and NGOs, specific EU and national endeavours are needed. They should be based on the following priority actions to reduce youth unemployment and improve youth job prospects. The priorities for action should be seen as a contribution towards the employment target of 75% set out in Europe 2020.

The lack of decent job opportunities for young people is a widespread challenge throughout the global economy. Raising youth employment in our partner countries and notably in the EU's Neighbourhood will not only benefit them, but also have a positive impact for the EU. Youth employment has come even further to the fore of the global political debate in response to the crisis and recovery, underlining a convergence of policy priorities and stimulating policy exchange. This was highlighted by the ILO Global Jobs Pact, recommendations from the G20 Employment and Labour Ministers, the G20 Global Training Strategy or the OECD Youth Forum.

5.1. Help to get the first job and start a career

After finishing secondary school, young people should either get a job or enter further education - and if not, they must receive appropriate support through active labour market or social measures, even if they are not entitled to benefits. This is important, particularly in Member States with few job openings, so that young people are not left behind at an early stage. A prerequisite is to ensure that young people have wider, earlier access to these measures, even if they are not registered as jobseekers. For young people with a migrant background or belonging to specific ethnic groups, more tailored measures may be needed to improve the progress made by this fast growing youth population, who often experience particular difficulties in starting their career.

Graduates from vocational pathways and from higher education also need support to move as quickly as possible into their first full-time job. Labour market institutions, especially Public Employment Services, have the expertise to inform young people about job opportunities, and to give them job search assistance – but they need to adapt their support to the specific needs of young people, particularly through partnerships with training and education institutions, social support and career guidance services, trade unions and employers, who can also offer this kind of support as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policy.

Employers, when offered a choice between an experienced worker and a novice, will often prefer the former. Wage arrangements and non-wage labour costs can provide an incentive to employ new entrants, but should not contribute to precariousness. Collective bargaining can also play a positive role in setting agreed differentiated entry wages. Such measures should also be complemented by secondary benefits and access to training to help young people remain in a job.

Young workers are very often hired via temporary contracts, which may allow firms to test skills and productivity of workers before offering them an open-ended job. However, too often, temporary contracts are just a cheaper alternative to permanent ones, particularly in countries where the gap in dismissal regulations between these contracts is high (i.e. severance pay, notice periods, possibility to appeal to courts): then the result is a segmented labour market, where many young workers experience a sequence of temporary jobs alternating with unemployment, with little chance of moving to a more stable, open-ended contract and incomplete contributions to pension provisions. Young women are particularly at risk of falling into this segmentation trap. The successive use of such contracts should be limited, since its is bad for growth, productivity and competitiveness[35]: it has long-lasting negative effects on human capital accumulation and earnings capacity, as young temporary workers tend to receive lower wages and less training. Possible ways to tackle this are to introduce fiscal incentives to firms using permanent contracts or for the conversion of temporary contracts into permanent ones. In order to shed further light on this particular context, the Commission will present in 2010 a comprehensive analysis of factors affecting the labour market outcomes for young people and the risks of labour market segmentation affecting young people.

5.2. Support youth at risk

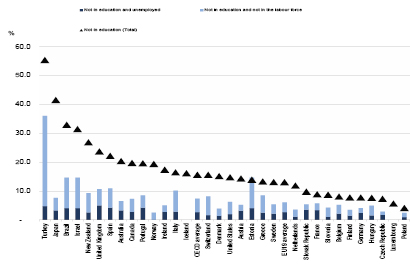

Indicators for youth labour market performance do not fully capture the fact that an astonishing 15% of European 20-24 year olds are disengaged from both work and education (NEET youth: neither in employment, education or training) and risk being permanently excluded from the labour market and dependent on benefits. It is essential, as a first priority, to tackle this problem, to provide suitable pathways for these young people to get back into education and training if needed or to bring them in contact with the labour market. Every effort should also be made to ensure as many young people with disabilities or health problems as possible are in work, to minimise risks of future inactivity and social exclusion. Public Employment Services are crucial to boost and coordinate such efforts. One option is to develop partnerships and agreements with employers who are offered special support for recruitment of youth at risk.

5.3. Provide adequate social safety nets for young people

Active inclusion of young people, with particular focus on the most vulnerable groups, requires a combination of adequate income support, inclusive labour markets and access to quality services[36]. Many unemployed young people, especially if they have never worked, have no access to unemployment benefits or other income support. To address this problem, access to social benefits, where appropriate, should be ensured, and where necessary, expanded to provide income security, while, at the same time, effective and efficient activation measures and conditionality should ensure that benefits are only awarded if the young person is engaged in active job search or in further education or training. This is of key importance to avoid benefit traps. Modernisation of social security systems should address the precarious situation of young people.

A growing number of young people are being moved onto (permanent) disability benefits. While some may not be able to work fully, even with suitably adapted workplaces, others could find a way back to the labour market through well designed activation policies.

5.4. Support young entrepreneurs and self-employment

A life-time job with the same employer is certainly not going to be the norm: most workers will change companies several times, and most current and future jobs are in SMEs and micro-enterprises. In addition, self-employment is an important driver of entrepreneurship and can thus significantly contribute to job creation, especially in the services sector.

Self-employment offers a valuable opportunity for young people to make use of their skills and shape their own job. It is also an option to be considered seriously by those helping young people to plan their career paths. The interest and potential of young people to become entrepreneurs needs to be strongly encouraged by fostering entrepreneurial mindsets and attitudes in education and training. This should be supported by the public and private sectors. To this end, young people need more opportunities to have entrepreneurial experiences, to receive support and guidance on business plans, access to start-up capital and coaching within the starting period. Here also, Public Employment Services have an important role, in informing and advising young jobseekers about entrepreneurship and self-employment opportunities.

Key new actions:

The Commission will:

- In order to address public spending constraints, work with Member States to identify the most effective support measures, including job placement, training programmes, recruitment subsidies and wage arrangements, security measures and benefits combined with activation and propose adequate follow-up actions.

- Establish a systematic monitoring of the situation of young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs) on the basis of EU-wide comparable data, as a support to policy development and mutual learning in this field.

- Establish, with the support of the PROGRESS programme, a new Mutual Learning Programme for European Public Employment Services (2010), to help them reach out to young people and extend specialised services for them. This programme will identify core elements of good practices in Public Employment Services and support their transferability.

- Strengthen bilateral and regional policy dialogue on youth employment with the EU's strategic partners and the European Neighbourhood, and within international fora, particularly the ILO, OECD and G20.

- Encourage the greater use of support to potential young entrepreneurs via the new European Progress Micro-finance Facility[37]. The Facility increases the accessibility and availability of microfinance for those wanting to set up or further develop a business, but having difficulties in accessing the conventional credit market. In many Member States young micro-entrepreneurs who seek funding under the Micro-finance Facility will also benefit from guidance and coaching with the support of the ESF.

In the framework of Europe 2020 and the European Employment Strategy, Member States should focus on:

- Ensuring that all young people are in a job, further education or activation measures within four months of leaving school and providing this as a "Youth Guarantee". To this end, Member States are asked to identify and overcome the legal and administrative obstacles that might block access to these measures for young people who are inactive other than for reasons of education. This will often require extending the support of PES, using instruments adapted to the needs of young people.

- Offering a good balance between rights to benefits and targeted activation measures based upon mutual obligation, in order to avoid young people, especially the most vulnerable, falling outside any social protection system.

- In segmented labour markets, introducing an open-ended "single contract" with a sufficiently long probation period and a gradual increase of protection rights, access to training, life-long learning and career guidance for all employees. Introducing minimum incomes specifically for young people and positively differentiated non-wage costs to make permanent contracts for youngsters more attractive and tackle labour market segmentation, in line with common flexicurity principles.

6. Exploiting the Full Potential of EU Funding Programmes

Several existing programmes already support the Youth on the Move objectives. For education and training, the Lifelong Learning programme (including Erasmus, Leonardo da Vinci, Comenius and Grundtvig), Youth in Action, Erasmus Mundus, Tempus and Marie Curie Actions address specific target groups. Their objectives should be strengthened, rationalised and better used to support the Youth on the Move objectives.

Teachers, trainers, researchers and youth workers can act as mobility multipliers at different levels: persuading young people to participate in a mobility experience, preparing the participants, staying in contact with the host institution, organisation or enterprise. In the next generation of mobility programmes, the Commission will propose a greater focus on increasing mobility of multipliers, such as teachers and trainers, to act as advocates for mobility.

The Commission will examine the possibility to step up the promotion of entrepreneurship mobility for young people, in particular by increasing Erasmus work placement mobility, promoting entrepreneurship education in all levels of the education system and in the EIT, enhancing business participation in Marie Curie actions and by supporting the "Erasmus for young entrepreneurs" initiative.

These programmes alone, however, will not be able to cater for all demands. Hence, there is a need to link up funding from many sources and have wider engagement of public authorities, civil society, business and others in support of the Youth on the Move objectives, to achieve the critical mass required.

The European Social Fund (ESF) provides considerable help to young people. It is the main EU financial instrument to support youth employment, entrepreneurship and the learning mobility of young workers, to prevent school drop-out and raise skill levels. A third of the 10 million ESF beneficiaries supported each year are young people, and about 60% of the entire ESF budget of 75 billion euros for 2007-2013 plus national co-financing benefits young people. The ESF also significantly supports the reforms of Member States' education and training systems and participation in life long learning, contributing 20.7 billion euros.