Session 2009/2010

Third Report

Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

Report on the

Committee’s Inquiry into

the funding of the arts in

Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings, Minutes of Evidence,

Memoranda and written submissions Relating to the Report

Ordered by The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure to be printed 12 November 2009

Report: NIA 05/09/10R (Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the NI Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure and has a role in the initiation, consideration and development of legislation.

The Committee has the power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Barry McElduff (Chairperson)

Mr David McNarry (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Dominic Bradley

Mr Kieran McCarthy

Mr PJ Bradley ***

Mr Raymond McCartney **

Mr Francie Brolly

Ms Michelle McIlveen *****

Lord Browne

Mr Ken Robinson *

Mr Trevor Clarke ****

* Mr Ken Robinson replaced Mr David Burnside with effect from 18 June 2007

** Mr Raymond McCartney replaced Mr Paul Maskey with effect from 10 March 2008

*** Mr PJ Bradley replaced Mr Pat Ramsey with effect from 29 June 2009

**** Mr Trevor Clarke replaced Mr Jim Shannon with effect from 15 September 2009

***** Ms Michelle McIlveen replaced Mr Nelson McCausland with effect from 15 September 2009

Table of Contents

Report

1. Per capita spend on the arts – comparisons with other countries/regions

2. Methods for sourcing additional funding

3. Measuring the economic and social benefits of the arts

5. Arts funders – comparisons with other regions

6. Art forms not receiving adequate funding

Appendices

3. List of Written Submissions to the Committee

4. Written Submissions to the Committee

5. List of Witnesses who gave oral evidence to the Committee

8. List of Additional Information considered by the Committee

9. Additional Information considered by the Committee

Executive summary

Purpose of the Report

The arts are one of the key spending areas for the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. However, over recent years there has been a growing concern at the relatively low levels of funding to the arts in Northern Ireland as compared to other countries and regions.

In this report, the Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure has sought to establish how and to what level the arts are funded in Northern Ireland by the public and private sectors, the impact of this funding, and how monies are allocated across the various art forms.

Main Findings

The Committee came to the conclusion that there is a lack of information regarding how much money the public sector invests in the arts. Research is required to ascertain how much government departments, other than the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure, spend on the arts.

In order to increase funding for the arts an inter-departmental approach is required, as the social and economic benefits of the arts meet the objectives of a range of departments.

In relation to allocating existing funding, the Committee came to the view that more money should be spent on community and voluntary arts, given their impact on regenerating communities and providing people with opportunities for participating in arts activities.

The Committee was particularly concerned that arts groups in communities without a history of arts funding should be pro-actively encouraged to access available monies. To this end the Committee recommends that the Start Up programme operated by the Arts Council continues and develops.

List of recommendations

1. We recommend that DCAL undertakes research to ascertain how much money is being spent on the arts by other government departments. This information should be used by DCAL and the Arts Council to gain a wider understanding of where arts funding is currently being targeted and to identify areas which receive little or no funding from any department.

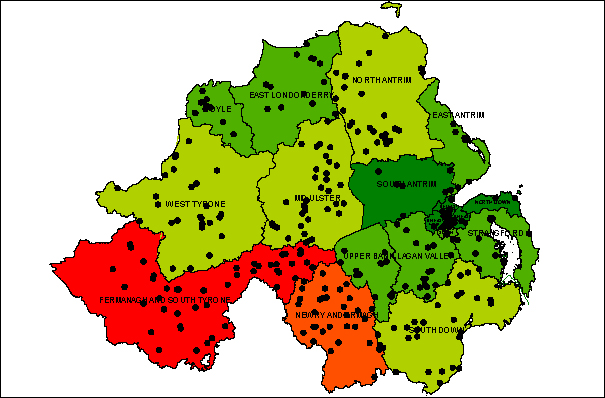

2. We recommend that DCAL works with local councils post-RPA to assist them in reviewing how much they spend on the arts, with a view to ensuring that there is a greater degree of equality in arts provision across the different council areas than exists presently.

3. We recommend that DCAL targets its investment in the arts in such a way as to further embed the arts in people’s everyday lives right across Northern Ireland. The Committee is of the view that greater participation and access to the arts will lead to greater support both among the public and within government for increased funding for the arts.

4. We recommend that DCAL sets up an inter-departmental group on funding for the arts.

5. We recommend that the Arts Council pro-actively seeks out arts organisations that may be eligible for EU funding and assists those organisations in making applications for such funding.

6. We recommend DCAL and the Arts Council work together so that budgets for coming years can be finalised in the January ahead of the new financial year in April, so that arts organisations are given as much prior notice as possible of their funding position.

7. We recommend that DCAL and the Arts Council work with Arts & Business NI to ensure that more support is given to community based arts organisations in terms of accessing private sponsorship.

8. We recommend that the Arts Council increases the level of funding which goes to community arts organisations.

9. We recommend that the Arts Council requires professional arts organisations which it funds to increase the amount of outreach/community work they currently deliver.

10. We recommend that the Arts Council sets up a specific funding programme for community arts organisations that deliver participation opportunities to people living in Super Output Areas ranked in the top 20% of areas of deprivation according to the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure.

11. We recommend that the Arts Council increases the current budget for the Start Up programme which will distribute grants to community based groups which have received little or no previous funding from the Arts Council.

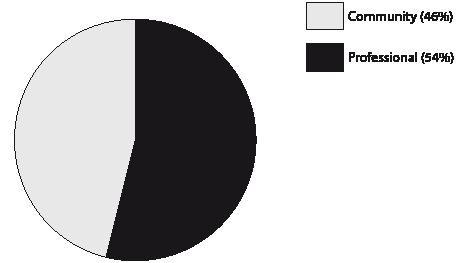

12. We recommend that in distributing these funds, the Arts Council pro-actively identifies groups which may be eligible for this funding.

13. We recommend that given its levels of participation, we recommend that the Arts Council increases the level of funding which goes to voluntary arts organisations, such as those involved in amateur drama or the traditional arts.

14. We recommend that in the interests of transparency and fairness, the Arts Council should establish a feedback process for unsuccessful funding applicants to clarify why they did not receive funding.

Introduction

Inquiry Terms of Reference

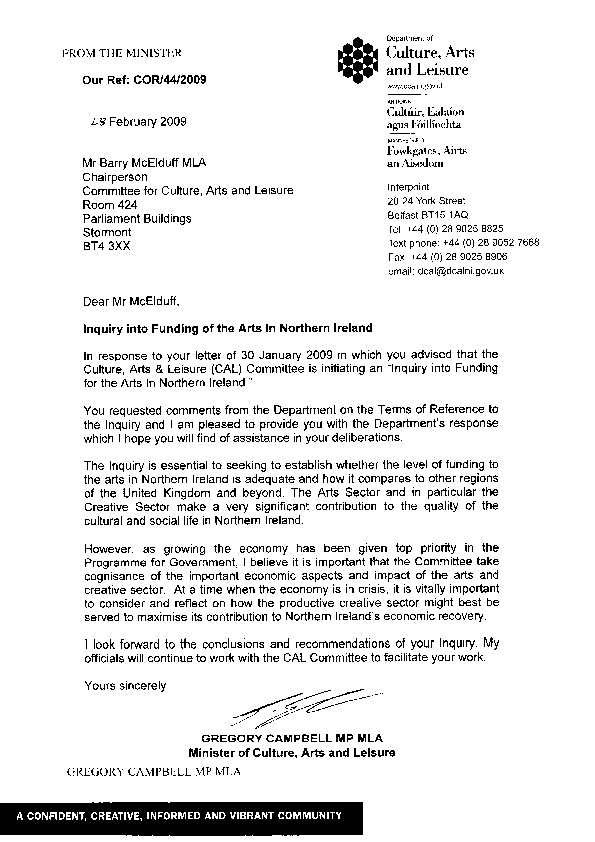

1. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure agreed to conduct an inquiry into the funding of the arts in Northern Ireland on 8 January 2009. The terms of reference for the inquiry were agreed at the Committee meeting on 29 January 2009.

Terms of Reference for the Funding of the Arts

- To compare the per capita spend on the arts in Northern Ireland with that of other European countries/regions, and to establish the rationale which other countries/regions have used in order to increase their spend on the arts.

- To explore innovative approaches of sourcing additional funding across the arts sector, including reviewing models of best practice that exist elsewhere.

- To carry out a stocktake of the research which has been carried out to date, regarding the measurement of the economic and social benefits of investing in the arts.

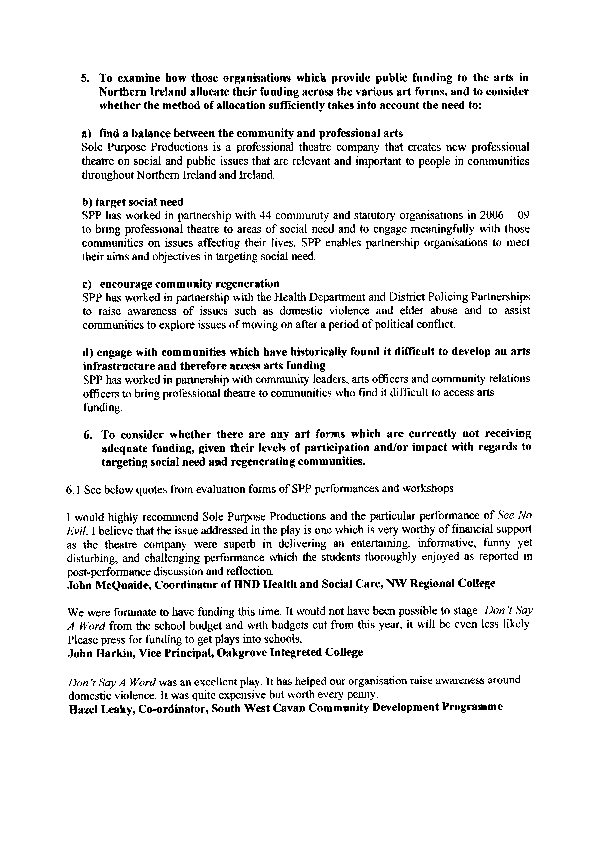

- To examine how those organisations which provide public funding to the arts in Northern Ireland allocate their funding across the various art forms, and to consider whether the method of allocation sufficiently takes into account the need to:

a) find a balance between the community and professional arts sectors;

b) target social need;

c) encourage community regeneration; and

d) engage with communities which have historically found it difficult to develop an arts infrastructure and therefore access arts funding.

- To compare those organisations which provide public funding to the arts in Northern Ireland with similar organisations across these islands, in terms of how they allocate funding across the various art forms.

- To consider whether there are any art forms which are currently not receiving adequate funding, given their levels of participation and/or impact with regards to targeting social need and regenerating communities.

- To report to the Assembly making recommendations to the Department and/or others.

The Inquiry Process

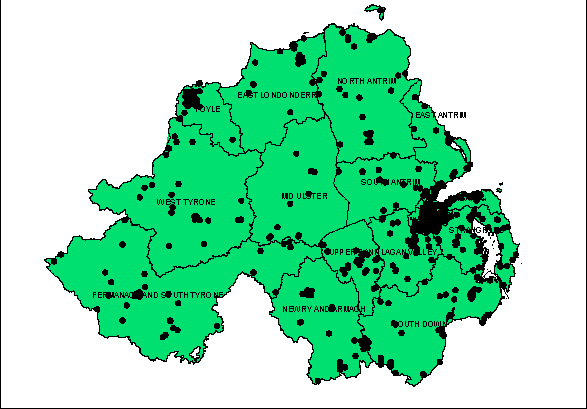

2. The Committee made the decision to hold an inquiry into the funding of the arts on 8 January 2009. Advertisements requesting submissions by 27 February 2009 were placed in the local newspapers on 3 February 2009. In addition, the Committee agreed to write to 134 individuals and interest groups, to request submissions on each of the matters included within the terms of reference. A list of those individuals and groups that submitted evidence is attached at Appendix 3.

3. The Committee received 71 submissions and considered oral evidence from 20 key stakeholders, including the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. A list of witnesses who provided oral evidence to the Committee is attached at Appendix 5. Transcripts of the oral evidence sessions are attached at Appendix 2.

4. In addition the Committee received additional information, to further inform the inquiry. A list of the additional information considered by the Committee can be found at Appendix 8. Copies of these additional papers are included at Appendix 9.

5. The Committee also commissioned 9 research papers on funding of the arts:

- The first paper examined the economic and social benefits that can be derived from sport, arts, museums and libraries in both the UK and USA.

- The second paper outlined the decision of the Project Steering Group in relation to the PricewaterhouseCoopers study to abandon Phase 2 of the research into the economic modeling of quantifiable benefits of the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

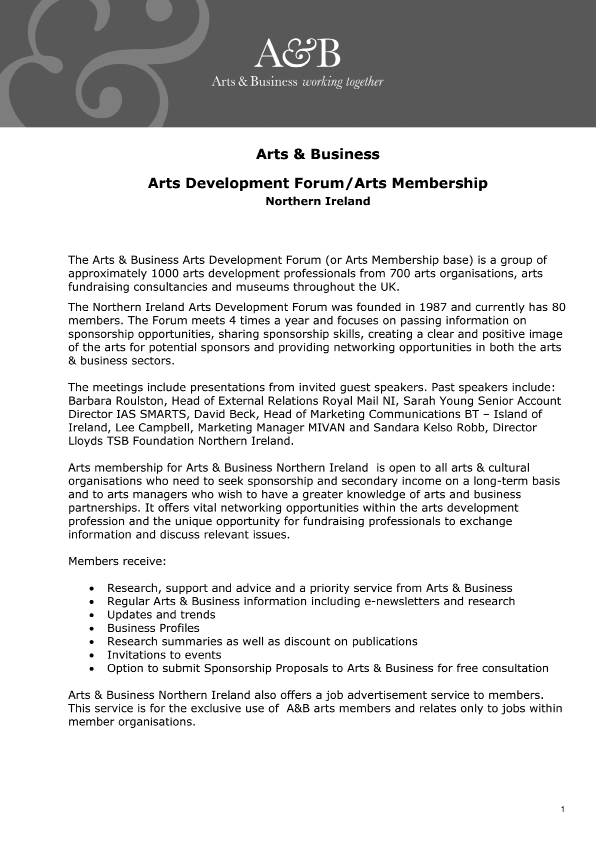

- The third paper looked at the funding relationships between the arts and the business sector throughout the regions in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

- The fourth paper examined the per capita spend on the arts in the UK and Republic of Ireland.

- The fifth paper highlighted the social impacts of the Arts.

- The sixth paper provided details on the levels of funding for arts and culture in various European countries. The paper highlighted individual countries approaches to funding and the mechanisms they use to contribute to the arts and culture.

- The seventh paper addressed further issues regarding per capita spend breakdown in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

- The eighth paper looked at the auditing and monitoring procedures within the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s grant management processes.

- Finally, the ninth paper provided further insight into the social impacts of the arts. It considered health, participation amongst those with a disability, and grants awarded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Copies of these papers are included in Appendix 7.

6. On 17 September and 1 October 2009 the Committee reviewed the evidence to the inquiry.

7. The Committee considered sections of a draft report at its meetings on 8 October, 15 October, 22 October and 5 November and on 12 November 2009 the Committee agreed its final report and ordered that the report be printed.

Acknowledgements

8. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure would like to express and record its appreciation and thanks to all the organisations who contributed to the inquiry.

Chapter 1

Per capita spend on the arts –

comparisons with other countries/regions

Per capita spend figures

9. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (ACNI) has produced per capita arts spend figures for Northern Ireland. The latest figure available is for 2008/2009 and is £7.58. Northern Ireland has the lowest figure for the UK and Ireland. The figures for the other regions are:

- England - £8.47

- Wales - £10.10

- Scotland - £14.04

- Republic of Ireland - €17.92[1]

10. The figure for Northern Ireland is based only on what the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL) spends on the arts, and does not cover capital spend. Funding for the arts from other government departments is not included. The ACNI explained:

For comparative purposes, we agreed with the other arts councils what we would and would not count. None of the other arts councils take into account spend from other Government Departments or local authorities. We are talking about per capita spend from central Government, from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, from DCAL, and from their counterparts in the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly. Those are the figures that we are using for comparison.[2]

11. The per capita figure produced by the ACNI does not include spend on the arts by local government, the private sector or philanthropic giving/donations. The ACNI told the Committee that it could not provide a figure on the spend on the arts by all government departments and by local councils, and that to do so would require an extensive piece of research.[3]

12. However, the evidence submitted by DCAL, both in writing and orally, questioned the per capita figure produced by the ACNI and its usefulness in understanding funding for the arts in Northern Ireland.

13. In his evidence to the Committee, the Minister queried the value of a figure which does not include all public expenditure on the arts:

The first point is about per capita spend on the arts. Currently, there is no universally accepted indicator of that nature, which creates a difficulty. It is vital that any comparisons made are like for like and that they adequately capture all public expenditure on the arts here and in other jurisdictions . . . In Northern Ireland, however, money may well come in from the Exchequer and be directed into another Department, but still end up by an indirect route being spent on the arts. It is important to take all those factors into account when we are looking at figures . . . .[4]

14. DCAL also made the point that Northern Ireland may have different needs than other regions in terms of the level and scale of arts provision. For example, during oral evidence DCAL officials made the point that the per capita figure for spend on the arts in Scotland (£14.04) includes funding for the Scottish Opera, the Scottish Ballet and the National Theatre of Scotland. Similar institutions do not exist in Northern Ireland, and it was the Department’s view that it is not clear whether Northern Ireland has the capacity for such organisations:

For example, Scotland has the Scottish Ballet and a national theatre. We do not have those, and we do not know whether we could sustain them if we did. If a comparison is undertaken, it is important to understand what is being compared and whether a region such as Northern Ireland needs exactly the same investment as other regions.[5]

Comparisons with other countries/regions

15. The ACNI was of the view that comparisons between spend on the arts in Northern Ireland with other European countries/regions were not feasible. They explained:

It is difficult to directly compare spending on the arts in many European countries and regions with that of the UK. That is because of different systems of support for creative and cultural life and the way in which they are defined in different countries and, even, in different regions of the UK. The ranges of legal structures and cultural policies that exist also have an effect . . .Other European countries have different funding models. For example, many countries, instead of having arm’s-length bodies, have ministries of culture that directly fund museums and heritage organisations and perhaps national companies. However, those ministries tend not to fund the independent arts sector, including the community and voluntary sectors. Therefore, it is difficult to draw comparisons with other European countries.[6]

16. The Arts Council of Ireland was of the same view, and made the point that:

To compare the way in which different jurisdictions fund the arts is like comparing apples and oranges.[7]

17. This view was backed up by a research paper commissioned by the Committee. That paper made the point that in most countries spend on culture only refers to contributions made by the culture ministry, and that there is a lack of a coherent definition of culture. Comparisons are further hampered by the fact that most European countries/regions present spend on the arts in terms of a percentage of GDP, rather than by using a per capita spend figure.[8]

18. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee came to the view that there is a lack of clarity regarding the amount of funding which is spent on the arts in Northern Ireland. It is not currently known how much local councils and the various departments spend on the arts. Given that there is considerable variation between local councils in terms of their arts budgets, there is perhaps the opportunity to leverage more funding from the arts through this source. This option could be explored as part of the Review of Public Administration. This point was made by Voluntary Arts Ireland who suggested:

We also recommend that the Department grasp the opportunity presented by the review of public administration (RPA) . . . There may be an opportunity for the Department, when looking at moving funding across to local authorities, to encourage them to match that and encourage some sort of continuity or consistency across the different local authorities, because it will vary. It can be quite random what is done in one area compared to another.[9]

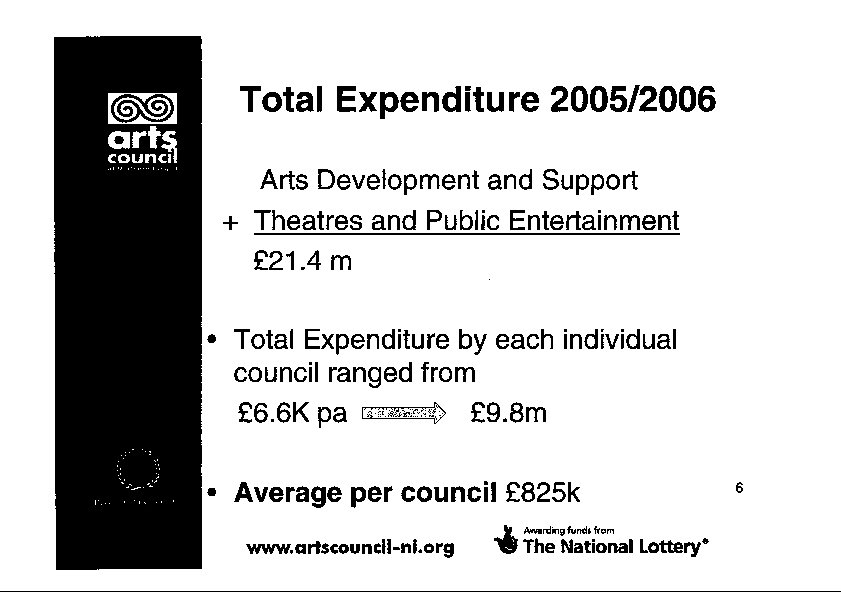

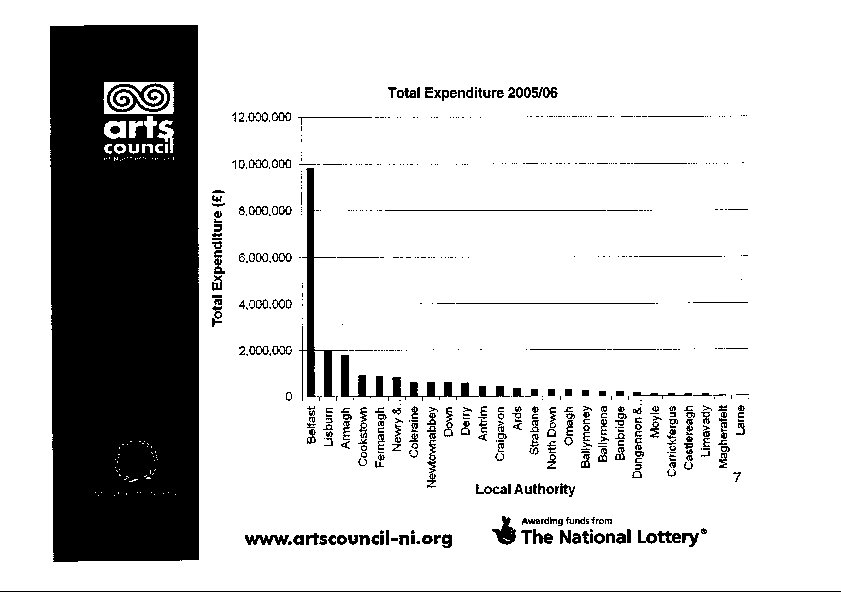

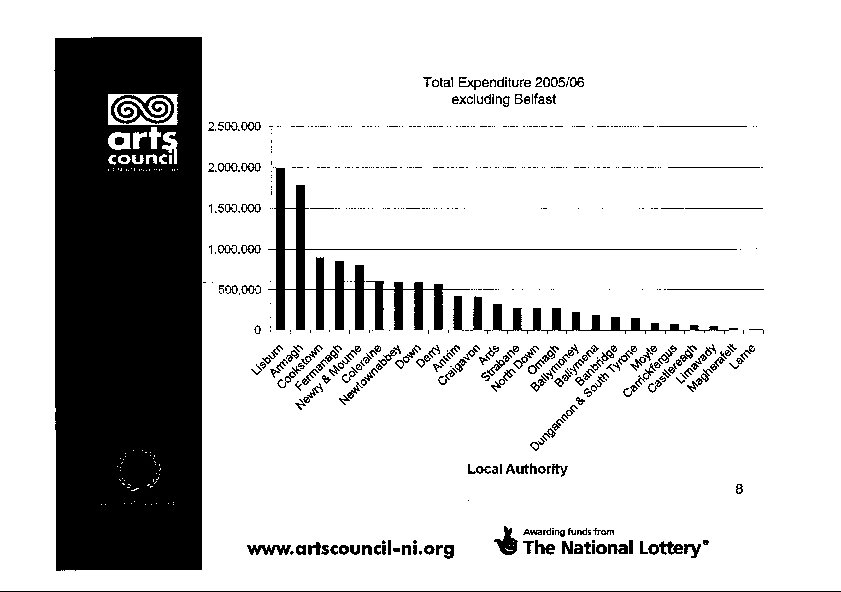

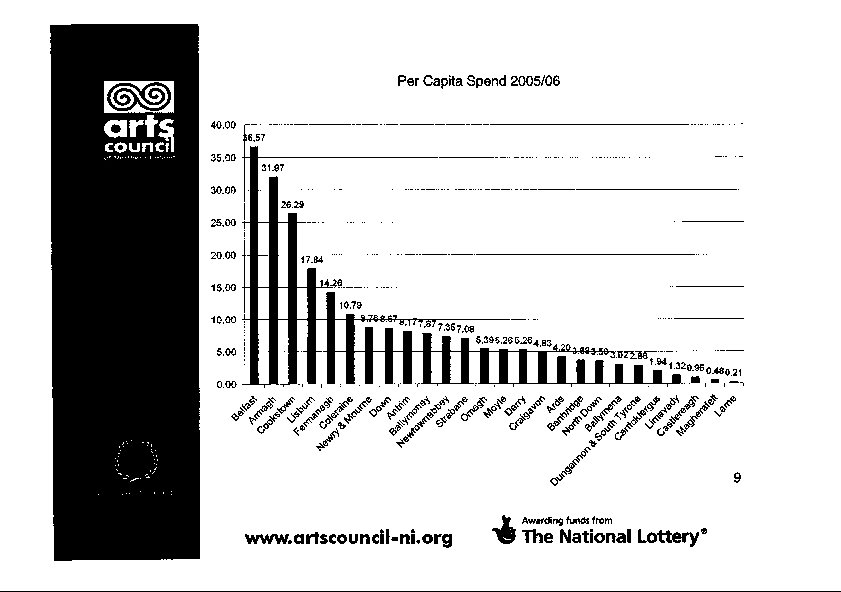

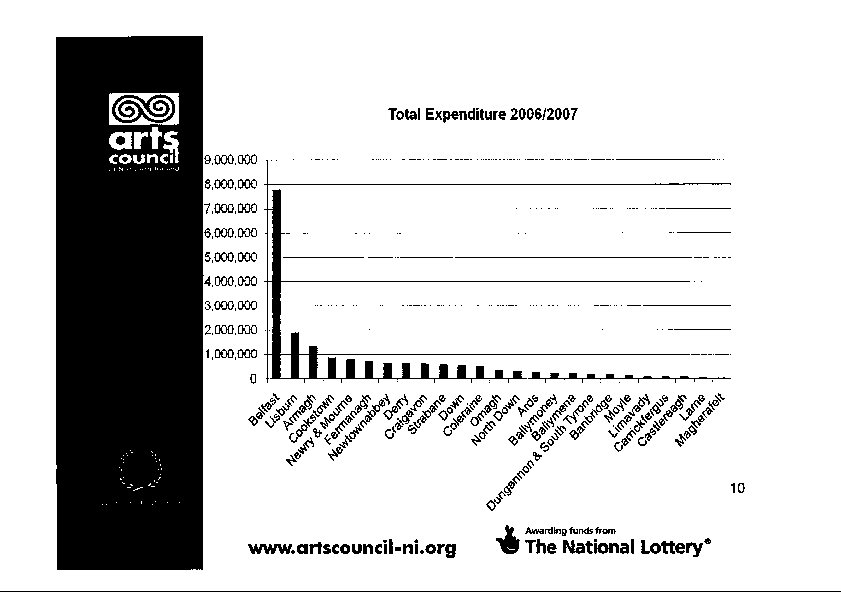

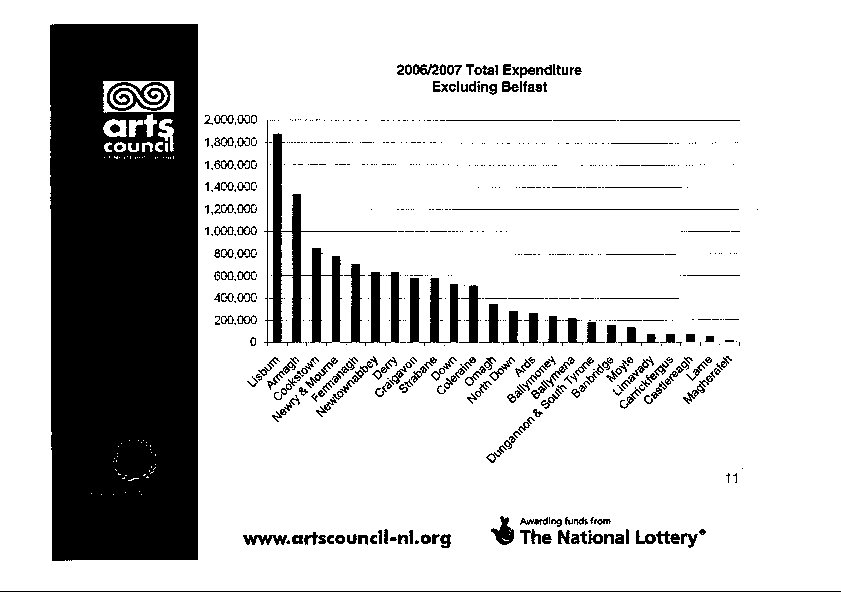

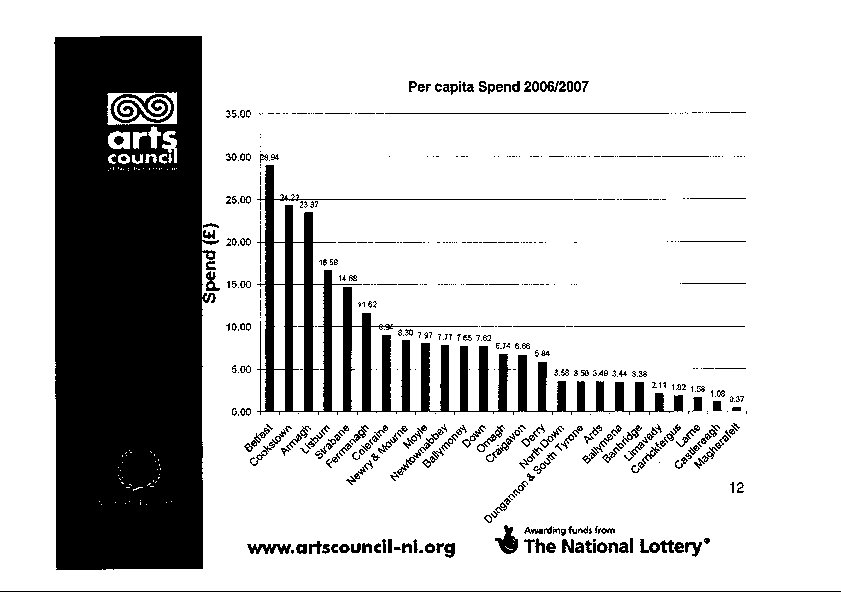

19. The FLGA also drew attention to the variation in spend between the 26, soon to be 11, local councils:

There are 26 local authorities, each of which operates in a different way . . . Some councils do not place as high a value on the arts. I cannot speak for them, but that is an area of concern for all of us and for the Committee . . . Per capita spend ranges from £30 down to 37p in certain areas. The range is colossal.[10]

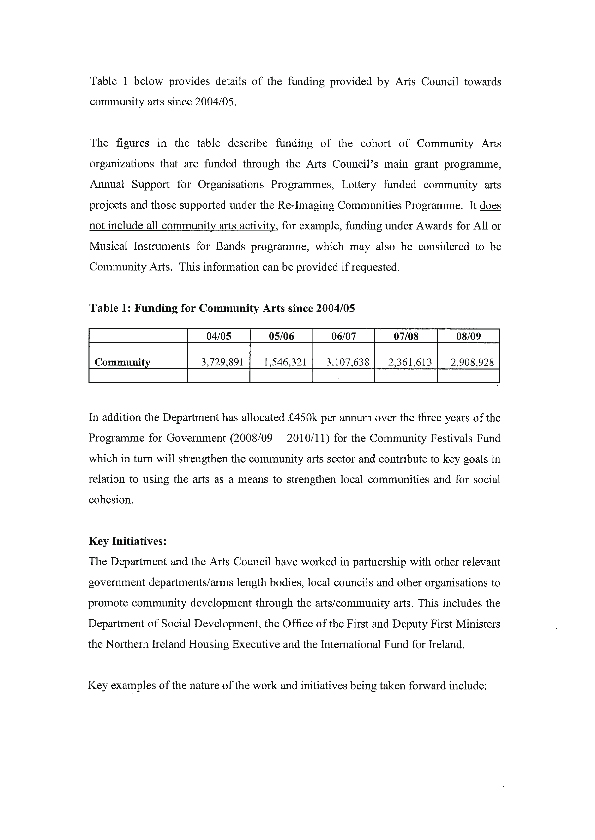

20. The Arts Council provided details of its most recent local authority arts expenditure survey from 2006/2007. The per capita spend per council is set out in the table below:

Council |

Per capita spend |

|---|---|

| Belfast | £28.94 |

| Cookstown | £24.22 |

| Armagh | £23.37 |

| Lisburn | £16.58 |

| Strabane | £14.68 |

| Fermanagh | £11.62 |

| Coleraine | £8.94 |

| Newry and Mourne | £8.30 |

| Antrim | £8.17 |

| Moyle | £7.97 |

| Newtownabbey | £7.77 |

| Ballymoney | £7.65 |

| Down | £7.62 |

| Omagh | £6.74 |

| Craigavon | £6.66 |

| Derry | £5.84 |

| North Down | £3.58 |

| Dungannon and South Tyrone | £3.50 |

| Ards | £3.49 |

| Ballymena | £3.44 |

| Banbridge | £3.38 |

| Limavady | £2.11 |

| Carrickfergus | £1.82 |

| Larne | £1.58 |

| Castlereagh | £1.08 |

| Magherafelt | £0.37 |

21. Based on the evidence presented the Committee makes the following recommendations:

We recommend that DCAL undertakes research to ascertain how much money is being spent on the arts by other government departments. This information should be used by DCAL and the Arts Council to gain a wider understanding of where arts funding is currently being targeted and to identify areas which receive little or no funding from any department.

We recommend that DCAL works with local councils post-RPA to assist them in reviewing how much they spend on the arts, with a view to ensuring that there is a greater degree of equality in arts provision across the different council areas than exists presently.

Rationale used by other countries/regions to increase funding

22. The Committee acquired information on two different regions which have in the recent past increased their funding of the arts. The Committee obtained information relating to the Republic of Ireland from the Arts Council of Ireland, and information on Liverpool through a study visit as part of the inquiry.

23. The Arts Council of Ireland was of the view that in its case, the growth in funding for the arts had resulted from investing in the arts at a grass roots or community level. In the 1980s the Arts Council of Ireland undertook a capital development programme which focused on every town having its own arts centre. In its view this led to a normalisation of spend on the arts, as the arts became embedded in people’s every day lives. It explained:

Back in the 1980s, rather than simply sending the arts on tour by having shows touring around the country, we decided to also build up an indigenous arts community or arts practice in every town and village. That was done so that every county, town or village would have its own artist and its own very particular and distinctive type of artistic impression. That is where it started; I do not think that there have been any simple and immediate, or expedient and pragmatic arguments made. I really believe that the arts must be embedded into the society in which people spend their day-to-day lives.[11]

24. The Arts Council of Ireland further made the point that public support is crucial for the arts to be able to attract funding:

Investment comes from the taxpayer and is guarded and administered by politicians. Investment will not be made unless the body politic really believes that the arts is important to people’s day-to-day lives. Our argument is based on those beliefs and values.[12]

25. In addition, the economic value of the arts in terms of the creative industries, cultural tourism, and their role in attracting foreign investment have also been put forward as reasons to fund the arts in the Republic of Ireland:

. . . the most recent Fáilte Ireland report indicates that that industry is worth €5·1 billion. An industry that is worth €5·1 billion is riding on public investment of about €80 million, which represents very good value for money. Furthermore, such an international reputation brings in foreign investment also . . . It is difficult to measure, but there is no doubt that, according to visitor surveys, it appears that people do not come here for the weather. They come here because they have built up an expectation from the films and television programmes that they have seen. One of the key things about tourism is that it has to deliver on that expectation. Therefore, traditional music sessions — whether in the pub, the club or outdoors — are important. The fact that it is a living tradition is critical . . . As well as making sense for lots of intrinsic reasons, it makes economic sense that, if you want to attract and retain inward investment, culture is one of the pieces of the jigsaw.[13]

26. During its evidence, the ACNI also referred to the economic arguments put forward in the Republic of Ireland for investing in the arts:

Culture was seen as a driver of the wider economy, and the investment that was made in arts and culture was regarded by successive Governments as a proud example of a mature and culturally confident society on a world stage.[14]

27. In the case of Liverpool, the Committee was informed that the impetus behind the city’s bid for the Capital of Culture title 2008, which required a significant expenditure on the arts, was both to boost the economy and tourism, and as a way to regenerate communities. The Lord Mayor of Liverpool quoted research which claims that being capital of culture generates 14,000 new jobs for a city and attracts £2 million in investment.

28. In terms of how more money could be levered for the arts in Northern Ireland, the Minister told the Committee that he recognised the many benefits of the arts:

It is clear that there is much support for the arts sector and a genuine desire to ensure that appropriate levels of funding are allocated to the arts to enable the sector to continue to grow and develop. It is also apparent that there is widespread recognition of the many benefits to be gained from such funding. The arts and creative sectors contribute to the cultural, social and economic life of all the people of Northern Ireland. In addition, the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL) estimates that more than 36,300 people were employed in the creative industries or creative occupations in Northern Ireland in 2007. That equates to 4·6% of the workforce, which demonstrates the significance of the creative sector. It has been recognised for some time that the most prosperous economies are characterised by a strong creative sector. Creativity generates innovation, and the two are inseparable. In turn, innovation drives productivity by introducing new and higher value added products and processes, leading, ultimately, to wealth creation.[15]

29. However, the Minister made the point that resources were limited and that DCAL has to compete against other departments in terms of budgets:

I recognise that we have a responsibility to make the case for the importance of arts funding. However, it would be unrealistic to do so without recognising the very tight public expenditure conditions in which we currently work. We are competing with other Departments for scarce resources and we need to be realistic as to what we can achieve and deliver.[16]

30. On the basis of the evidence presented the Committee makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that DCAL targets its investment in the arts in such a way as to further embed the arts in people’s everyday lives right across Northern Ireland. The Committee is of the view that greater participation and access to the arts will lead to greater support both among the public and within government for increased funding for the arts.

Chapter 2

Methods for sourcing

additional funding

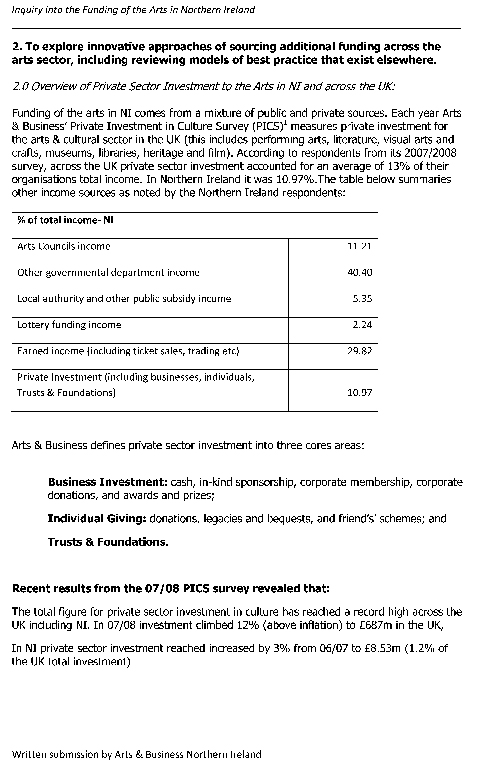

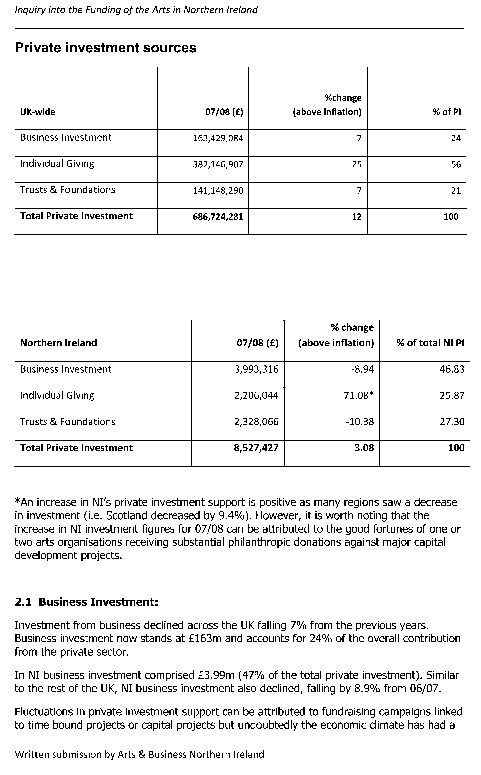

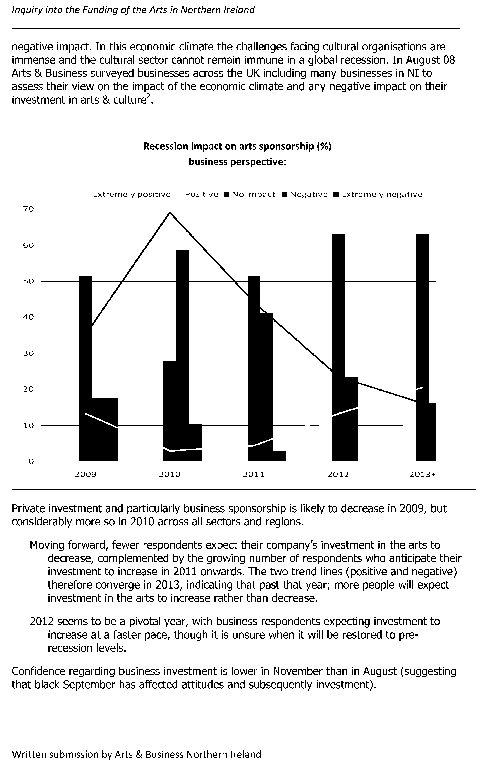

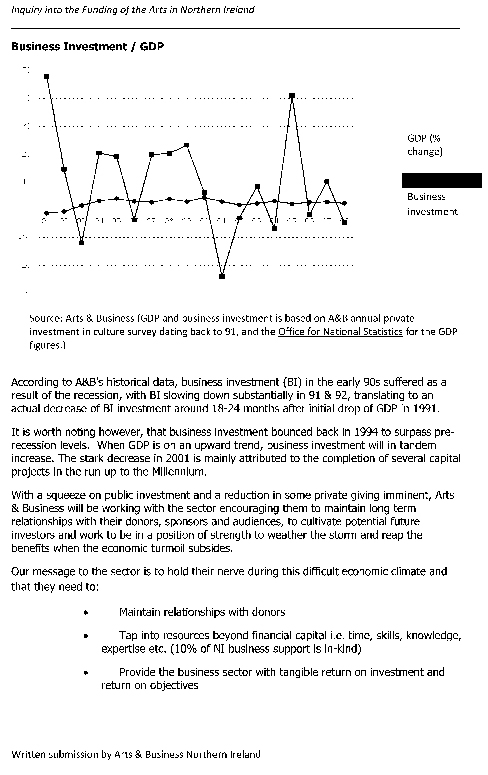

Encouraging more private sector investment

31. During the course of the inquiry the Committee discovered that arts organisations in Northern Ireland are already using a range of different methods to try to obtain funding in addition to what they receive from the public purse.

These methods include:

- Private sponsorship

- Box office income

- Membership schemes

- Fund raising events

- Social enterprise

- Trading

32. Arts & Business NI in their evidence to the Committee made the point that there is the potential to increase the level of philanthropic giving, gift aid, and business support for the arts. However, levering this suppport requires time and resources:

. . . there is definitely an opportunity around trusts and foundations. The key factor in that regard is the lack of staff in Northern Ireland and the lack of time.[17]

33. In relation to community arts organisations, Arts & Business NI were of the view that the opportunities were there:

There is a lot of potential — particularly in community areas — to engage with communities and businesses in those regions. With the right skills, training and resources, arts organisations and community organisations can still get a return.[18]

34. However, community arts groups told the inquiry that they needed more help to access private funding. Such groups usually do not have the staff to be able to devote time to sourcing potential sponsorship. Mid Armagh Community Network explained the difficulties:

Some local businesses may sponsor a cup for a competition, but, beyond that, we have not had a great response from private sponsors.[19]

35. ArtsEkta were of the view that more support was needed from government to help them access private sector sponsorship:

If bodies such as Arts and Business, the Arts Council or DCAL openly acknowledge that some arts organisations are carrying out events that could be of benefit to businesses, that is an endorsement that could possibly lead to arts organisations receiving greater support from the business sector. Arts & Business tends to rely on us doing all the work and it then supports us, but another side to its work should be to present opportunities to businesses.[20]

36. New Lodge Arts were of a similar opinion:

An increase in the lobbying of potential funders might help. Perhaps the Department could meet prospective funders and provide opportunities for them to meet representatives of the sector to find out more about the potential benefits to them. It has been extremely difficult for us as a small organisation.[21]

37. Given the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that DCAL and the Arts Council work with Arts & Business NI to ensure that more support is given to community based arts organisations in terms of accessing private sponsorship.

The need for a cross departmental approach

38. In terms of new ways of obtaining additional funds, many arts organisations suggested that there needed to be more emphasis on departments other than DCAL investing in the arts. A number of organisations made the point that the work they carry out meets the objectives of a range of departments. For example, ArtsEkta said:

As I said, we do all sorts of cultural diversity and section 75 work. It has been quite a challenge for our organisation to go to the racial equality unit here and request core funding. We do not meet its requirements, as it does not fund any arts projects. It pushes us towards the NI Arts Council, which has recently given us project funding.[22]

39. The lack of recognition by other departments of how arts organisations are relevant to their priorities was also mentioned by Féile an Phobail:

There are massive tourism and social-development aspects of our programme, yet we receive little or no support from DSD. We have brought up the matter locally and at MLA level, but we have had no joy in getting what we should receive.[23]

40. Belfast Community Circus School also emphasised the cross-departmental value of its work:

There needs to be connectivity. What we are going to be contributing to Northern Ireland’s economy and society will meet the Department of Education’s objectives for youth work; the Department for Social Development’s objectives for community and capacity building; and tourism objectives. Therefore, responsibility should not fall to simply the Arts Council.[24]

41. There was a strong feeling among those who gave evidence to the inquiry that DCAL should set up an inter-departmental group to encourage other departments to invest in the arts. This point was made by the FLGA, Belfast Community Circus School, Young at Art, New Lodge Arts, the Lyric Theatre, ArtsEkta, Féile an Phobail, and the Community Arts Forum.

42. ArtsEkta were of the view that a cross-departmental strategy or policy could lead to more funding for the arts overall:

Along with the arts sector, the Arts Council could be lobbying for an inter-departmental arts policy across all Departments. If every Department were to have a ring-fenced budget for the arts, that would help to increase the per capita spend on arts in the region.[25]

43. CAF put forward a similar argument:

If there were a cross-departmental policy, such as those of the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), every Department would have some responsibility for the delivery of the arts and for supporting the arts. There should be some acknowledgement and recognition that the arts have an impact on all areas of Government. Therefore, all Departments should have responsibility for the arts, and it should not fall back solely on DCAL.[26]

44. Voluntary Arts Ireland highlighted the fact that other departments have much larger budgets at their disposal compared to DCAL. Therefore, if these departments could be persuaded to spend even a very small percentage of their budget on the arts, this could pay significant dividends:

It is not a magic answer, but, in most cases, the other Departments to which we talk have budgets that are enormous compared to the culture budget. To lever out a small part of such a budget is of benefit to the arts as a whole and to the work of the Culture Department.[27]

45. The Lyric Theatre made the point that a cross-departmental strategy would also help to raise the profile of the arts and embed them in people’s everyday lives:

The Arts Council, the Government and the media need to find a combined approach, through joined-up thinking, and develop a strategy to increase the profile of the arts throughout society. They need to help people to realise how it affects them on every level.[28]

46. When questioned on this topic the Arts Council were not averse to the idea of a cross-departmental strategy for the arts, but cautioned that other departments needed to bring funding to the table:

We believe that the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL), which is our parent Department, should lead the co-ordination of funding. I add a note of caution in that looking at the arts without additional funding may not bring about the result that we need, which is more funding. The establishment of an interdepartmental co-ordinating mechanism needs to come with a commitment to increase funding.[29]

47. The Minister’s view was that although there is no cross-departmental strategy for the arts, DCAL does work with other departments on specific projects:

At present, there is not a cross-departmental or formal strategy for the arts. Having said that, however, as members will be aware, the Department works with other Departments on various initiatives that support the arts sector, an example of which is the Re-imaging Communities programme, in which the Department for Social Development, the Department of Education, the International Fund for Ireland and the PSNI are all involved. There are many examples of cross-departmental working.[30]

48. However, the clear view coming from the arts sector is that they believe a formalised cross-departmental approach to the arts would bring benefits, and that an ad hoc approach regarding certain projects was not sufficient. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee therefore makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that DCAL sets up an inter-departmental group on funding for the arts.

The need for longer funding cycles

49. Arts organisations were of the view that one method of assisting their financial situation would be to change the length of funding cycles. At present funding is awarded by the Arts Council on a 1-year basis, with some organisations being given an indicative budget for 3-years. However, some arts organisations reported that a 3-year cycle was not long enough. Féile an Phobail explained:

Equally, however, Féile an Phobail’s long-term objectives are not helped by the current funding arrangements, which mean that the longest that we can plan to fund certain posts for is three years. That does not help us to achieve a five- or 10-year plan, which féile and other festivals across the city and beyond hope to implement, so that we can help to stimulate tourism and community regeneration.[31]

50. Similarly CAF said:

We also recommend that, in consultation with the arts sector, DCAL and ACNI should develop and implement a long-term funding strategy and introduce appropriate five- to 10-year funding programmes. That would help support stability and sustainability in the sector. Arts Council funding packages are for three years, and, even within that, it is necessary to reapply year on year.[32]

51. Other organisations made the point that although they were awarded 3-year funding in principle, in reality funding was only confirmed on an annual basis. The Lyric explained:

We are part of a three-year funding programme with the Arts Council, but it is three-year funding in name only, because the Arts Council is wholly reliant on funding from the Department that is provided on a yearly basis.[33]

52. The Arts Council’s evidence backed up this point, as they explained:

On the Exchequer side of the house, we admit three-year clients to give them a modicum of stability. We ask for a three-year programme of activity, and each year we ask them to give us the programme for the next year. As the Committee knows, the confirmation of our funding comes on an annual basis only. Often, our funding decisions are not confirmed until February . . . However, the sad reality is that that is the way that Government funding works and we can only pass on what we have. We have tried to move to three-year funding.[34]

53. The Minister confirmed that DCAL can only confirm budgets on a 1-year basis:

The Department is tied into the wider public expenditure process, which means that its budgets are confirmed for one year only and it cannot give formal commitments outside that. I do not know whether there is scope for the Arts Council to do something on the basis of a semi-formal understanding.[35]

54. The Minister also made the point that the downside to a 3-year or longer funding commitment is that there is less flexibility and scope for new organisations to receive funding for the first time:

A difficulty with three-year funding is that it commits large amounts of money and smaller organisations that are trying to get in for the first time can have some difficulty. Longer-term funding has pros and cons that need to be considered carefully.[36]

55. The Committee understood both arts organisations’ frustrations at only being able to plan spend one year ahead, but at the same time is cognisant of the fact that departmental budgets are only confirmed on an annual basis. However, the Committee would like to see DCAL and the Arts Council working together to ensure that decisions on a coming year’s budget are taken at as early a stage as possible. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee therefore makes the following recommendation:

We recommend DCAL and the Arts Council work together so that budgets for coming years can be finalised in the January ahead of the new financial year in April, so that arts organisations are given as much prior notice as possible of their funding position.

Access to EU funding

56. In terms of accessing more funding, some arts organisations were of the view that EU funds were a potential source of untapped resources. However, these organisations stated that they require more assistance and guidance from the Arts Council in terms of accessing this money. For example, Belfast Community Circus School made the following point:

It is rather sad that the Arts Council does not play a proactive role in identifying any funding outside its own remit. Sadly, we have probably missed a lot of boats in respect of European funding. Certainly, if one looks across at Gateshead and Newcastle, their cultural renaissance was brought about through a combination of the National Lottery and Government agencies linking in with European moneys; whereas, over here, we have, apparently, an expert on European funding in the Arts Council, but that has never seen results . . . My point is that, in essence, applying for European funding will be complicated and complex, and, without any support and guidance, scary . . We need someone with expertise to sit down with groups and explain how the application process works.[37]

57. The Committee received correspondence from the Arts Council at a late stage of the inquiry process (29 October 2009) on what it is doing to assist local arts groups access the €400 million EU Culture Programme Fund. The Committee was concerned that the Arts Council had only invited 12 groups to an event on 06 October 2009 promoting the Culture Programme. Given the current constraints on departmental budgets, the Committee thinks it is vital that alternative sources of funding for the arts in Northern Ireland should be fully explored. It therefore makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that the Arts Council pro-actively seeks out arts organisations that may be eligible for EU funding and assists those organisations in making applications for such funding.

Chapter 3

Measuring the economic and

social benefits of the arts

The ValCAL study

58. It is widely accepted that investing in the arts has a range of benefits on very many different fronts. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) in their evidence to the inquiry summarised these impacts as follows:

The arts have an economic development impact through direct employment and income. Earlier, members talked about the spend that is associated with people going out for a night to an arts event, or a community arts festival that brings people together, as a result of which people spend more money in the shops. There is a tourism impact. The arts have the potential to attract visitors to the area, and there is strong evidence that tourists come to Northern Ireland to visit its arts venues and festivals. There is an education impact. The arts contribute to the education sector and therefore, in relation to public spending, save the public purse by adding to the quality of the education system. There is a health impact as well . . . The final area of impact is social inclusion and community cohesion, including, potentially, a reduction in crime.[38]

59. It was against this recognition of the value of the arts, among the other activities funded by DCAL, that the Department commissioned PWC to carry out a study of the social and economic value of its business areas. This study was completed in 2007 and is entitled “Research into the Social and Economic Value of Culture, Arts and Leisure in Northern Ireland" (known as the ValCAL Study).

60. During the oral evidence sessions, PWC explained the background to the study:

The study was trying to see if there is a model that can demonstrate impact. For example, if the Department puts £X million into a particular project or programme, what jobs, employment and income — what economic measurables — will that produce?[39]

61. However, the ValCAL Study did not proceed beyond phase 1 because it became apparent that there was a lack of sufficient data to carry out a meaningful assessment of the economic and social benefit of investment. As PWC said:

We discovered that there is not a lot of information available about some of the economic impacts that would allow us to build a model.[40]

62. Departmental officials in their evidence to the inquiry backed this up, setting out the obstacles as follows:

. . . it was felt from the evidence that was presented in the phase 1 report that there was not sufficiently robust data to allow us to go forward and produce an economic model that we could stand over.[41]

Other evidence

63. In their written submissions, arts organisations referred to numerous studies which attempt to measure or quantify the impact of investment in the arts. For example, the Lyric Theatre referred to economic studies carried out on itself and the Grand Opera House:

KPMG and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland carried out economic studies on both the Lyric Theatre and the Grand Opera House. There is evidence to suggest that every £1 of funding that the Arts Council invests in the Lyric Theatre generates £3·25 in the local economy. That is a significant economic driver. The Grand Opera House is an economic generator, because it contributes more than £5 to the local economy for every pound that it receives in public subsidies.[42]

64. The Lyric Theatre referred to the economic importance of the creative industries:

Of Northern Ireland’s population, 4·6% — about 33,000 people — are currently employed in the creative industries, which puts them on a par with agriculture. That compares with the average of 6·8% for the rest of the UK. In an Assembly debate on 9 October 2007, the then Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure, Edwin Poots, reported that emulation of what was occurring in the rest of the UK could potentially generate the substantial figure of a further 11,000 new jobs in the creative industries in Northern Ireland.[43]

65. The FLGA also flagged up the role of creative industries in the economy going forward:

I notice that the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts has said that the creative industries are predicted to be a major high- growth contributor to the UK economy in the next five years. That information was published on 9 March, so its facts are up to date. That organisation says that, on average, creative industries are set to grow by 4%, which is more than double the rate of the rest of the economy. By 2013, the number of creative businesses is likely to have risen from 157,000 to 180,000, with employment of 1·3 million people, thus outstripping the financial sector.[44]

Difficulties in measuring economic and social benefits

66. Despite the various studies referred to above, it is clear that there are problems in measuring the effectiveness or impact of a particular piece of artistic endeavour. The Lyric Theatre stated:

We achieve a lot, but our achievements are difficult to put down on paper. Nowadays, people require facts and figures. They want to know how many people watched a play, but one cannot make value judgements about how effective a play is or how it affected those who viewed it.[45]

67. Féile an Phobail also referred to the problems of measuring benefits, particular on the individual:

Measuring the exact impact of community events is a grey area. I have not heard of anyone — from here to the States — who has been able to do that. It is hard to measure the social impact of the arts, particularly on individuals.[46]

68. This point was backed up in the research papers provided to the Committee by Assembly Research Services. During an oral evidence session, the researcher explained the problems of quantifying both economic and social benefits:

Impacts such as community cohesion, education, reduction in crime and social inclusion are complicated to quantify. The difficulty with these impacts is their nebulous nature. With many of these impacts, the benefits cannot be measured initially or in financial terms. Any benefits derived are more likely to be seen at a local and community level, rather than providing an overarching regional benefit. It is more appropriate to provide benefit ratios for types of projects and initiatives, but it is not appropriate to estimate the benefit ratio of funding at the individual community and regional levels. The data is either not available or does not lend itself to analysis at those levels.

Economic impact analysis is concerned with identifying and measuring the changes that occur, or would be likely to occur, in an economy as a direct or indirect result of a new public and private initiative. Indirect costs and benefits can prove more difficult to evaluate, particularly if they have no market price. A cost-benefit analysis attempts to determine the value of an activity to society as a whole. That economic methodology sees the social value of an activity as based on individual valuations of that activity, with a focus on economic efficiency.[47]

Lack of resources required to measure impact

69. In addition to the methodological issues, a number of arts organisations made the point that measuring the impact of their activities would require resources which they do not have. For example, the Ulster Orchestra stated:

I can only offer anecdotal evidence. We do not have the resource to follow that up in a scientific way. It would be wonderful to take a large sample of pupils and follow them from Key Stage 1 through to the end of their education and into their working life in order to see how many people stay with us.[48]

70. Féile an Phobail made a similar point:

It is a matter of funding — we would love to do another economic audit of our annual festival programme, but it comes down to whether we put funding towards a festival or towards an economic audit.[49]

71. In his evidence to the Committee, the Minister also referred to the cost of carrying out the necessary research to measure the impact of the arts:

However, there is no commonly agreed approach to the measurement of that, nor is there an accepted multiplier that can easily be applied to capture direct and indirect employment and productivity effects. That lack of a commonly agreed approach has been widely recognised, and to attempt to assess the impact at a Northern Ireland level would require a bank of relevant data to be collected, which would then need to be built up and quality assured. That would take time to construct and would require additional resources.[50]

72. Based on the evidence, the Committee came to the conclusion that there is a lack of specific research about the benefit of the arts in Northern Ireland. However, there are problems both in capturing and analysing the data, particularly in relation to the benefits of the arts at a community or individual level. At the same time, any research which could be produced will be of benefit in terms of making the case, particularly to government departments outside DCAL, of the clear benefits of investing in the arts.

Chapter 4

Distribution of funding

Balance of funding between community and

professional arts

73. Stakeholders made the point that there are overlaps between professional and community arts. Professional organisations do some work in communities, and some community groups would describe their work as highly professional.

74. For example, Voluntary Arts Ireland stated:

. . . as regards the arts in general, there is no clear distinction between the voluntary, community and professional arts. There is a lot of overlap, with the big beasts of the jungle and the insects all totally reliant on each other . . . professional arts could not survive without amateurs. Many professionals start as amateurs and many amateur groups employ professionals. That is an important part of the arts ecology.[51]

75. Similarly, the Ulster Orchestra made the point:

Our prime purpose is to be an excellent classical symphony orchestra and to have excellent access and outreach — one informs the other. We cannot have a true community arch without a centre of excellence.[52]

76. The Arts Council backed up the view that professional and community arts are intertwined:

The reality of artistic practice over the past 20 years or so has meant that the distinctions between the different branches of the arts, including community and professional arts, have lost much of their definition and significance. They are much more fluid. Many practitioners would no longer recognise themselves as belonging to fixed categories of artistic practice.

Many who work in communities describe themselves as highly professional, and that is a view to which we also subscribe. Professional artists of a high calibre also work in various community contexts.[53]

77. Furthermore, the Arts Council were of the view that professional organisations had begun to take a more serious interest in undertaking community based work in the recent past:

Over the past six or seven years, I have discerned a trend of change in the orientation of many arts organisations and a recognition that they need to go in and work in local communities. Education, outreach and access are not simply bolted on by organisations; they take that seriously, and we have encouraged them to do so for a long time.[54]

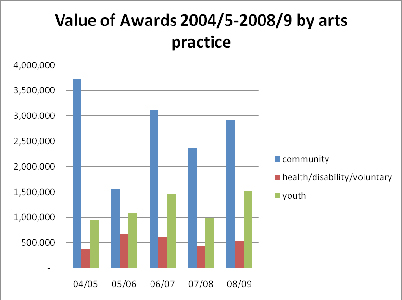

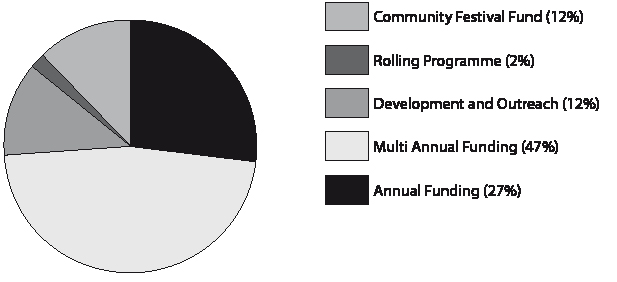

78. In relation to the question of how funding is distributed, the Arts Council told the inquiry that 20% of their funding goes on community art. However, various community arts groups which presented evidence to the inquiry stated that only 9% of the Arts Council’s budget goes towards community arts. The Arts Council provided the following explanation for the discrepancy in the figures:

The Arts Council disputes the figure of 9%. In my role in the Arts Council, I have a portfolio of clients who are classified as community arts clients. That is not to say that other organisations that funded through the arts councils do not carry out community arts activity. I assume that the figure of 9% is drawn from the portfolio that I look after as regards the Annual Support for Organisations Programme. Therefore, the figure of 9% is not a clear one. A number of organisations do not sit in my portfolio for operational reasons but do carry out community arts activity. For example, the Crescent Arts Centre in Belfast, Best Cellars Music Collective, which is based in east Belfast, and the Playhouse in Derry/Londonderry. They would see themselves as delivering community arts activity, but they do not sit in the community arts portfolio. Therefore, the grant, or the moneys, that we award them, would not have been calculated in that figure of 9%.

The figures in that breakdown show that in 2008-09, community arts were receiving around 20% of the grants that we gave out. [55]

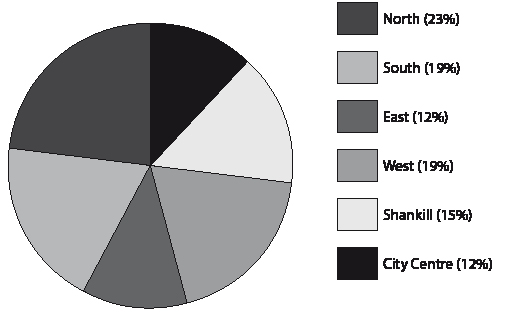

79. In terms of other public funders of the arts, Belfast City Council allocated 46% of its budget to community arts groups:

Some 54% of arts programme funding goes to professional arts organisations, and 46% goes to community-driven schemes, which reach participants on the ground. Therefore, a good balance has been created.[56]

80. However, the community arts organisations which presented evidence to the Committee were strongly of the view that more funding needed to be invested in community arts. This point was made by Greater Shantallow Community Arts, Arts Ekta, and CAF among others who stated that community arts have a tangible outcome in terms of regenerating communities and transforming individuals’ prospects and opportunities.

81. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that the Arts Council increases the level of funding which goes to community arts organisations.

82. When questioned by the Committee, the Minister made the point that because many professional groups in receipt of funding do community work, it is not possible to define spend on community arts as simply money allocated directly to community groups:

However the fusing of these sectors (professional and community arts) means that efforts to assess the actual spend on the community arts sector are more complex than a simple and crude assessment of funding to those organisations formally classified as the community arts sector.[57]

83. The Ulster Orchestra was one of those professional groups who provided information on the community outreach work it is involved in:

Although it is hard to give a number, there are probably 20 people constantly involved in that work. Sometimes we pull in other people for bespoke projects. However, close to a third of the orchestra is heavily committed to that work on an ongoing basis.

Everyone is involved when we stage full orchestra concerts as part of our outreach work for the education boards. However, at the individual level, people must want to do such work and be comfortable doing it. It is not what they were trained to do.

Some years ago, we went down the route of attempting to get everyone to do education work by making it part of the contract. However, someone is employed by the orchestra, in the first instance, because he or she is a wonderful clarinet player or trumpet player. That person might be death in a classroom and not suited to such work.[58]

84. While the Committee welcome the work currently being carried out by professional organisations, it believes there is scope for more initiatives in this area.

85. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that the Arts Council requires professional arts organisations which it funds to increase the amount of outreach/community work they currently deliver.

Funding to target social need

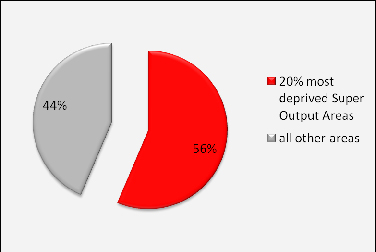

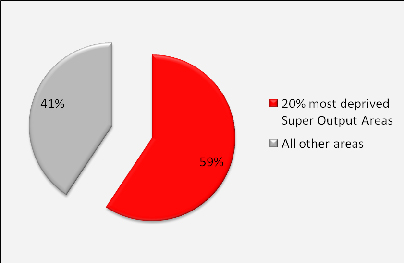

86. In their evidence to the inquiry, the Arts Council stated that they give 56% of their total funding to the 20% most deprived communities in Northern Ireland. In doing so, they claim they are working in such a way as to target social need. They stated:

The Arts Council is conscious of its obligation to target social need, and 56% of its funding goes to the 20% most deprived communities in Northern Ireland.[59]

87. However, a number of groups challenged the figures presented by the Arts Council and claimed that the methodology used to produce them is flawed. The Arts Council confirmed that the figures are based on the postcode of where the organisation in receipt of the funding is located.

88. Belfast Community Circus School made the point that this meant that funding for the Grand Opera House, which is located in a deprived area by postcode, would be included in these figures, despite the fact that its ticket prices would suggest that it is more likely to attract audiences from more affluent areas.[60]

89. Greater Shantallow Community Arts made a similar point in relation to funding for the arts in its area:

As of yesterday, the Arts Council’s website suggested that 97% of funding awarded in the Derry City Council area through the Arts Council’s programmes has gone directly to Londonderry’s most deprived areas. That leads me to ask — is our city centre deprived? It must be, because 97% of funding went to organisations based in the city centre.[61]

90. There did not seem to be any consensus within the arts sector on whether the Arts Council is distributing funding in a way which adequately takes account of targeting social need. While the Arts Council explained that they do give additional scores to applications from organisations who are operating in an area of social need, it does not appear that the Arts Council is actively seeking to fund a certain number of projects or allocate money to groups in areas identified as TSN areas.

91. Based on the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that the Arts Council sets up a specific funding programme for community arts organisations that deliver participation opportunities to people living in Super Output Areas ranked in the top 20% of areas of deprivation according to the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure.

Engagement with communities without a history of arts funding

92. The Committee heard evidence from three groups which reported that communities such as theirs without a history of accessing arts funding had found it difficult to break into the funding world. These groups were Cairncastle LOL, the Mid Armagh Community Network and the Ulster Scots Community Network.

93. Cairncastle LOL reported that until recently they had been unaware that that the Arts Council could fund small organisations like themselves:

We talked to the Arts Council this year, which was the first time. We never realised that the Arts Council could fund us.

It was only through luck that I got on to the Arts Council for Northern Ireland, which does not seem to sell itself. We attended a number of roadshows for funding bodies, but the Arts Council has never been represented.

We had not realised that the Arts Council could fund us. We thought that the Arts Council awarded grants of £50,000, £60,000 or £100,000 and that it was interested only in the more upmarket projects, not the grass roots.

We are just country folk who are trying to find our way. We need an organisation such as the Arts Council to work with us, advise us and point us in the right direction.[62]

94. Mid Armagh Community Network stated that they had found it difficult to build a relationship with the Arts Council, and that they felt that the needs of their group are not understood well:

In the early years, we found that a community group from a Protestant area was viewed with suspicion, because there was no history of community- group organisations in those areas, and that probably hindered us to some degree.

It is important for the organisation that funds any group to keep an eye on what that group is doing. A relationship should grow up between the two and there needs to be familiarity. We have extended invitations for various events at which we performed, including our annual concert. The response of the Arts Council in attending those showcase events was pretty poor.

. . . there is an onus on the Arts Council to be proactive in how it promotes the funding that it can make available, especially to Ulster-Scots groups. Perhaps it is down to a lack of awareness; groups may think that they cannot apply for funding because they do not realise what is there to be attained.[63]

95. The Ulster Scots Community Network supported the view put forward by Cairncastle LOL and the Mid Armagh Community Network that the Arts Council needed to do more to advertise its existence to those groups outside the funding circle. In their view the Arts Council should take a more pro-active strategic role and identify groups who need funding and help them make the applications:

The network receives funding from the Arts Council, but we need a more strategic and proactive approach from the Arts Council. In working with it, we are trying to build that relationship to our mutual benefit.

The major difficulty is that Ulster-Scots community groups have started from a low level . . . The groups lack the capacity, confidence and ability to tackle the major funding streams. The expertise does not exist on the ground to apply for the £30,000, £40,000 and £50,000 Arts Council projects.[64]

96. CAF, which is the umbrella organisation for community arts groups, argued that it is challenging for new groups to obtain funding for the first time because they are competing against well-established groups who know the system. They explained:

I will talk about some of the obstacles that groups face accessing funding. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (ACNI) is the main source of funding for the arts in Northern Ireland. Competition for those funds is very high. It can often be difficult for new and community-based groups to compete for funding with well-established arts groups that have been working for many years.[65]

97. In their evidence to the Committee, the Arts Council said that they recognised the difficulties for new groups, particularly for those who were located in communities without a strong arts infrastructure. In response to this need they have run the Start Up programme:

The STart UP programme was originally funded by DSD under its renewing communities programme, whereby we had £100,000 for a one-year programme; through our officers we provided developmental support and 100% grant aid to local organisations.

DSD funding ceased. However, we have found a small budget from our 2009-2010 resources and intend to resume that funding to seed-fund small organisations, which could move on to other schemes.

During the STart UP programme, we employed officers whose job it was to work in areas that had been identified as receiving low levels of funding. They worked with the community relations officers and local authority arts officers to identify groups that they could contact.[66]

98. The Committee welcomes the Start Up programme and believes it can help address the problem of small community groups being unaware or unable to access arts funding.

99. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

We recommend that the Arts Council increases the current budget for the Start Up programme which will distribute grants to community based groups which have received little or no previous funding from the Arts Council.

We recommend that in distributing these funds, the Arts Council pro-actively identifies groups which may be eligible for this funding.

Chapter 5

Arts funders – comparisons

with other regions

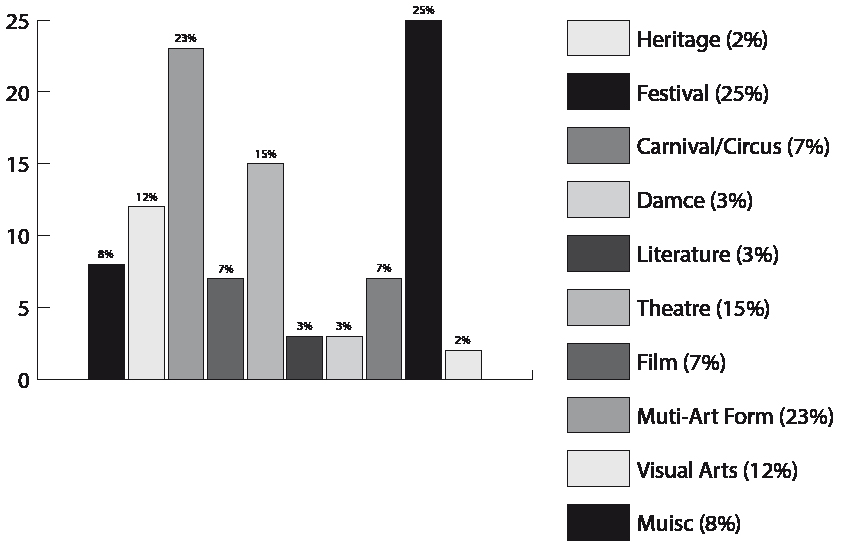

100. As part of the inquiry, the Committee was interested to learn whether data existed which would allow comparison between government funders of the arts across these islands. In particular, the Committee sought information on how the various funding bodies – in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, Scotland and Wales distributed their budgets between different art forms.

101. In its written submission, the Arts Council stated that this sort of information was not readily available:

Arts Councils in each of the UK regions and the Republic of Ireland support artists and arts organisations through Exchequer and Lottery funds. A breakdown across the various art forms for each of the Councils represents a significant piece of research in its own right owing to issues of consistency and comparability between budgets and systems of classification.[67]

102. The Minister made the point in his evidence that while such information would be useful, each region has different needs in terms of how it spends its arts budget:

It is important to understand and, where appropriate, learn from the funding- allocation process used by other organisations that provide public funding to the arts. However, every region is different and Northern Ireland, like other regions, has its own unique cultural demographic and social characteristics that are reflected in the allocation of funds to various art forms.[68]

103. This was backed up by the information provided by Assembly Research Services who pointed to the fact that different regions have their own leanings towards certain art forms, perhaps as a result of their cultural history:

There are differences in preferences among the EU countries in the allocation of public spending on culture. For example, spending on cultural heritage and museums is highly prioritised in Greece, Italy, Malta, Cyprus, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Performing arts, including music, theatre and dance, are primarily subsidised in Austria, Germany, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Denmark, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden.[69]

104. The Committee therefore came to the conclusion that while this kind of comparative data across the regions would be of interest, it may not necessarily be required to assist public funders of the arts in Northern Ireland in allocating their budgets.

Chapter 6

Art forms not receiving

adequate funding

Funding for voluntary arts

105. There are a range of art forms currently funded by the Arts Council and other public bodies and the Committee recognises the value of each of them. The Committee is also cognisant that budgets are currently stretched and that many arts organisations believe that more funding for the entire sector is required.

106. However, during the inquiry the Committee came to the view that voluntary arts is a sector that is underfunded and under-recognised in terms of the opportunities it gives people for participation. Voluntary Arts Ireland made the following point during their evidence:

The voluntary arts also make a key contribution to volunteering, the economy, lifelong learning, mental and physical health, regeneration, community cohesion, etc. Nobody joins an amateur arts group to make a contribution to regeneration or social cohesion. People join because they want to sing, act or dance. However, those community groups create a by-product that affects a lot of those other agendas, many of which pertain to other Departments.

For years, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) in England has had public service agreement targets to raise levels of arts participation, and for years it has singularly failed to meet those targets, largely because it works primarily through Arts Council England, which then charges its regularly funded organisations — about 800 arts institutions — with increasing participation. That is not where participation happens: it happens in small community groups that are not funded through any Government or Arts Council programme.[70]

107. The Committee noted that despite DCAL having Public Service Agreements with targets of increasing the number of people participating in arts activities, the Arts Council does not weight the number of people participating in a project when it is scoring applications:

There is no weighting given for the number of participants/audience as this varies greatly from organisation to organisation and from artform to artform. One of the principal criteria of all Council funding programmes is the artistic quality of the programme. We recognise that innovative/challenging work does not attract huge audiences but should be supported because of its developmental nature. The other principal criterion is that of public benefit which is assessed against the level of interaction with the public.[71]

108. Based on the evidence, the Committee therefore makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that given its levels of participation, we recommend that the Arts Council increases the level of funding which goes to voluntary arts organisations, such as those involved in amateur drama or the traditional arts.

Feedback for unsuccessful funding applicants

109. In terms of how the Arts Council makes decisions on allocating funding, some witnesses expressed a number of concerns about this process. CAF were of the view that some kind of appeals process was required:

In consultation with the arts sector, we would like DCAL and ACNI to develop and implement a transparent policy and procedures for reviewing ACNI decisions. At present, if groups do not receive ACNI funding, there is no appeals process, and that can be frustrating for groups.[72]

110. One such group, New Lodge Arts, spoke of its frustration at not been given a clear reason as to why its application for funding had failed:

A recent attempt by New Lodge Arts to secure Arts Council Annual Support for Organisations (ASOP) funding was unsuccessful, despite scoring highly in the application process. We were told that the application was unsuccessful because of standstill funding within the Arts Council and that funding had to be targeted at organisations that were seen to be more strategically important in the sector . . . I found it frustrating that, although we had scored highly, we did not get that funding . . Perhaps there could be more transparency around which organisations are funded and whether they are funded according to how well they meet the criteria or whether they are deemed to be more strategically important in the sector.[73]

111. Based on the evidence, the Committee therefore makes the following recommendation:

We recommend that in the interests of transparency and fairness, the Arts Council should establish a feedback process for unsuccessful funding applicants to clarify why they did not receive funding.

[1] Arts Council of Northern Ireland written submission, Appendix 4

[2] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[3] Additional Information, Appendix 9

[4] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[5] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[6] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[7] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[8] Research paper, Appendix 7

[9] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[10] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[11] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[12] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[13] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[14] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[15] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[16] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[17] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[18] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[19] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[20] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[21] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[22] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[23] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[24] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[25] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[26] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[27] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[28] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[29] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[30] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[31] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[32] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[33] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[34] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[35] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[36] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[37] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[38] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[39] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[40] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[41] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[42] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[43] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[44] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[45] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[46] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[47] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[48] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[49] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[50] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[51] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[52] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[53] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[54] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[55] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[56] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[57] Additional information, Appendix 9

[58] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[59] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[60] Additional information, Appendix 9

[61] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[62] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[63] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[64] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[65] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[66] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[67] Written submission, Appendix 4

[68] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[69] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[70] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[71] Additional information, Appendix 9

[72] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

[73] Oral evidence, Appendix 2

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Thursday 29 January 2009

Ulster American Folk Park, Omagh

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Dominic Bradley MLA

Mr Francie Brolly MLA

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr Nelson McCausland MLA

Mr Pat Ramsey MLA

Mr Jim Shannon MLA

Apologies: Mr David McNarry MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

In attendance: Dr Kathryn Bell (Clerk)

Mrs Antonia Hoskins (Assistant Clerk)

Mrs Elaine Farrell (Assistant Clerk)

Miss Mairéad Higgins (Clerical Supervisor)

Mrs Angela Aboagye (Clerical Officer)

The meeting opened in public session at 10.48 a.m.

6. Consideration of Draft Terms of Reference for Arts Inquiry

Agreed: The Committee agreed the terms of reference for the inquiry.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the press notice seeking written submissions for the inquiry.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the closing date for written submissions would be 27 February 2009.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the first oral evidence session would be with the Arts Council of Northern Ireland.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the second oral evidence session would comprise a presentation from Assembly Research and Library Services on the VALCAL study and related issues, along with a presentation from the authors of the VALCAL study and the Department.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12.40 p.m.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 5 February 2009

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr David McNarry MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Francie Brolly MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr Nelson McCausland MLA

Mr Pat Ramsey MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Mr Jim Shannon MLA

Apologies: Lord Browne MLA

Mr Dominic Bradley MLA

In attendance: Dr Kathryn Bell (Clerk)

Mrs Antonia Hoskins (Assistant Clerk)

Mrs Elaine Farrell (Assistant Clerk)

Miss Mairéad Higgins (Clerical Supervisor)

Mrs Angela Aboagye (Clerical Officer)

The meeting opened in public session at 10.35 a.m. The Deputy Chairperson took the Chair.

7. Inquiry into the funding of the arts

The Committee noted the outline plan for its inquiry into the funding of the arts.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 1.00 p.m.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 12 February 2009

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr David McNarry MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Dominic Bradley MLA

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr Nelson McCausland MLA

Mr Pat Ramsey MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Mr Jim Shannon MLA

Apologies: Mr Francie Brolly MLA

In attendance: Dr Kathryn Bell (Clerk)

Mrs Antonia Hoskins (Assistant Clerk)

Miss Mairéad Higgins (Clerical Supervisor)

Mrs Angela Aboagye (Clerical Officer)

Ms Meadhbh McCann (Research & Library Services)

Ms Ruth Barry (Research & Library Services)

The meeting opened in closed session at 10.36 a.m.

The meeting moved into open session at 12.45 p.m.

8. Inquiry into the funding of the arts

The Committee noted the response to the inquiry from the Committee for Finance and Personnel.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 1.05 p.m.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 19 February 2009

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)