Session 2007/2008

Third Report

COMMITTEE FOR THE OFFICE OF THE FIRST MINISTER AND DEPUTY FIRST MINISTER

Final Report on the Committee’s Inquiry into Child Poverty in Northern Ireland

VOLUME TWO

Written Submissions to the Committee, Witnesses Who Gave Evidence to the Committee, Research Papers, Other Evidence Considered by the Committee and List of Abbreviations

Ordered by The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and

Deputy First Minister to be printed 4 June 2008

Report: 08/07/08R (The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister is a Statutory Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 46. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental Budgets and Annual Plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of relevant primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the First Minister and deputy First Minister.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee is as follows:

- Mr Danny Kennedy (Chairperson)

- Mrs Naomi Long (Deputy Chairperson)

- Ms Martina Anderson

- Mr Tom Elliott

- Mrs Dolores Kelly

- Mr Barry McElduff

- Mr Francie Molloy

- Mr Stephen Moutray

- Mr Jim Shannon

- Mr Jimmy Spratt

- Mr Jim Wells

Table of Contents

Volume One

Section

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

1. Introduction

2. Approach of the Committee and focus of the report

3. Definition and measurement of child poverty

4. The evidence-base for the prevention of child poverty

5. Strategies to tackle child poverty in Northern Ireland

6. Policies to increase income

7. Tackling rising costs and financial exclusion

8. Promoting employment

9. Measures to tackle long-term disadvantage

10. Cross-cutting approaches

11. Conclusions

Appendices

1. Minute of Proceedings

2. Minutes of Evidence

Volume Two

Appendices

3. List of Written Submissions to the Committee

4. Written Submissions to the Committee

5. List of Witnesses Who Gave Evidence to the Committee

6. List of Research Papers

7. Research Papers

8. List of Other Evidence Considered by the Committee

9. Other Evidence Considered by the Committee

10. List of Abbreviations

Appendix 3

List of Written Submissions

Advice NI

Barnardo’s

Belfast Health Action Zone

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust

Children in Northern Ireland

Children’s Law Centre

Citizens Advice in Northern Ireland

Committee for Regional Development

Committee for Social Development

Consumer Council

Council for Catholic Maintained Schools

Craigavon Borough Council

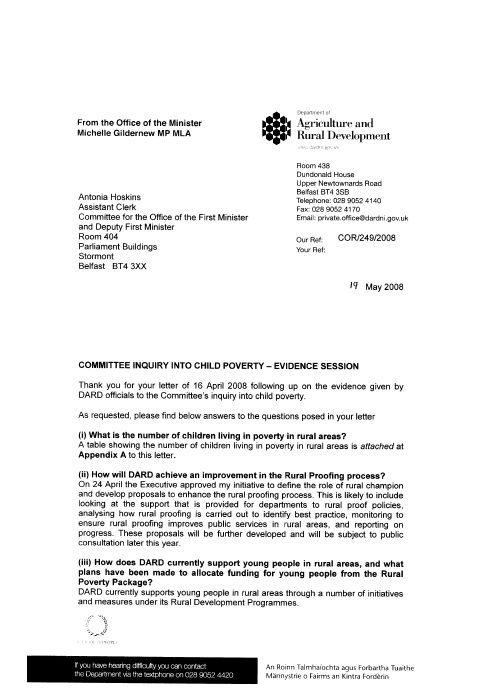

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

Department of Education

Department for Employment and Learning

Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

Department of the Environment

Department of Finance and Personnel

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

Department for Social Development

Derry Children’s Commission

Derry City Council

Disability Action

Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council

Eastern Health and Social Services Board

Equality Commission for Northern Ireland

Institute of Public Health in Ireland

Lisburn City Council

NCH Northern Ireland

New Policy Institute

Newtownabbey Borough Council

North Eastern Education and Library Board

Northern Ireland Anti-Poverty Network

Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People

Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action

Northern Neighbourhoods Health Action Zone

Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister

PlayBoard

Rural Community Network

Save the Children

Shelter Northern Ireland

Southern Area Childcare Partnership

Southern Health and Social Services Board

Voluntary Sector Housing Policy Forum

Western Area Childcare Partnership

Western Investing for Health Partnership and Western Health Action Zone

Appendix 4

Written Submissions to the Committee

Written Submission by:

Advice NI

Background

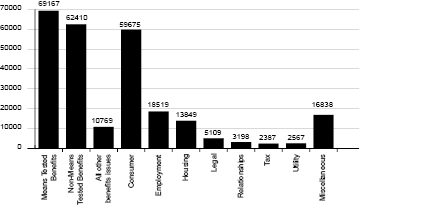

1. Advice NI is a membership organisation that exists to provide leadership, representation and support for independent advice organisations to facilitate the delivery of high quality, sustainable advice services. Advice NI exists to provide its members with the capacity and tools to ensure effective advice services delivery. This includes: advice and information management systems, funding and planning, quality assurance support, NVQs in advice and guidance, social policy co-ordination and ICT development.

2. Membership of Advice NI is normally for organisations that provide significant advice and information services to the public. Advice NI has over 70 member organisations operating throughout Northern Ireland and providing information and advocacy services to over 150,000 people each year dealing with over 237,000 enquiries on an extensive range of matters including: social security, housing, debt, consumer and employment issues. For further information, please visit www.adviceni.net.

3. In relation to child poverty statistics Advice NI would refer to the information produced specifically for Northern Ireland by specialist organisations such as Save the Children[1]. Advice NI members do contribute to the alleviation of child poverty on a daily basis and this response is grounded this work.

Summary

4. There is always a balance to be struck between encouraging families in receipt of social security benefit to move into paid employment and providing adequate support for families while they are in receipt of benefits.

5. In our view the Government has taken a predominantly ‘work focused’ approach, concentrating primarily on ‘making work pay’ and using employment as the principal means of tackling child poverty. However, in taking this approach, there is a concern that families on benefits are being left behind. In the body of this response we have identified some areas where effective action could be taken to address this situation.

6. In general terms, just as Government would urge those on benefits not to have a phobia about working, Advice NI believes that Government itself should not have a phobia about seeking to improve the quality of life for those people and children reliant on benefits.

7. There is also a concern that child poverty remains an issue for the ‘waged poor’, with a particular focus being those in low paid employment. The significant problems being experienced by low income families regarding the administration of tax credits has served to push many families into overpayment situations and hardship through no fault of their own. Advice NI also believes that the rate at which the National Minimum Wage has been set has not lifted working families out of poverty and has contributed to people becoming reliant on a poorly administered tax credits system.

Comments – Support for families on benefit

8. Focussing on families in receipt of social security benefits, there are a number of areas which could be addressed which would impact directly on child poverty.

9. Benefit uptake is obviously an area that requires ongoing attention. The fact that uptake of means tested benefits remains worryingly low means that many families on benefits are actually existing on income which is below the poverty line. Benefit uptake is highlighted within the Programme for Government and Advice NI believes that this is an area where local initiatives can be devised and delivered to maximum effect. Advice NI believes that benefit uptake programmes which depend on the advice sector for delivery must be undertaken at a rate of remuneration which means that the service is deliverable and sustainable over the longer term.

10. In much the same way as winter fuel payments have gone some way to addressing the issue of fuel poverty among older people, there is an opportunity to directly impact upon child poverty by providing financial support at critical times of need. The Social Fund Maternity Grant is an example of this but we feel that this principle could be extended to cover other key life events involving children. Advice NI would advocate the extension of this support to in-work ‘waged poor’ households.

11. Obviously children should be adequately fed and clothed as a minimum requirement. Spending on food can be budgeted on a weekly basis but it is often more difficult for families on benefit to budget for clothing for their children. Clothing can be a substantial expense (particularly in this age of designer labels) and assistance towards the cost of clothing for children would be welcome. There are various options for how this might be implemented including (i) allowance becomes automatically available for all children whose parents are in receipt of the appropriate benefits; (ii) allowance becomes available for children over the age of five years of age whose parents are in receipt of the appropriate benefits; (iii) reduced allowance for younger children to take account of possibility of some clothing being passed from one child to another.

12. The list of exclusions for which a Community Care Grant application can be made, should in our view be reviewed, with a view to allowing access for assistance with educational need. At the very least there needs to be co-ordination between the educational authorities and Social Fund in order that sufficient resources are available for the poorest children in order that they can meet basic educational requirements for example in terms of a school uniform.

13. Advice NI has already engaged with the educational authorities in Northern Ireland regarding the take-up of both school uniform grants and free school meals for school age children. Advice NI advocates that free school meals should be available to all children –mindful that this approach would guarantee that all children receive an adequate diet; remove any stigma regarding means testing of school meals provision and maximise take-up.

14. The function of Budgeting Loans should be reviewed. Budgeting Loans can be offered to applicants and, as opposed to Community Care Grants, these Loans require repayment via deductions from benefit. These deductions further reduce the families already restricted income, therefore any family repaying a Budgeting Loan fall below the minimum standard set by government, namely the Income Support level. Whilst these Loans do provide financial support at zero per cent interest, the deductions can have a significant impact on the budget of these low income families.

15. The amounts awarded by the Social Fund should be reviewed. Where these amounts are insufficient to meet the full costs of the item in question, applicants can be forced to seek money from other sources to meet their needs particularly at key times of the year including Christmas and birthdays. Due to problems accessing credit, these can be disreputable sources such as money lenders, who can charge excessive interest.

16. The issue of lone parents aged 16 – 18 in receipt of Income Support requires attention in our view. The personal allowance for the claimant is reduced by up to £23.50. A similar situation exists for couples where one or both are aged under 18. In our view the allowance should be comparable to that of lone parents aged over 18 / couples aged over 18. Any differentiation is bound to impact upon the child/ren, particularly considering the amounts of money involved.

17. This issue is in relation to young parents, and surely such young people should be given as much support as possible, and not penalised for having children.

18. Benefits sanctions, for example failure to carry out a job seeker’s direction, impacts upon the whole family and again there needs to be a balance between ‘encouraging’ people to move into employment and ensuring that these people are adequately supported while on benefit. Previous Advice NI Social Policy Papers (‘New Deal for Disabled People’; ‘The Contributory Principle – On the Agenda or in the Firing Line’ and ‘Welfare Reform: Challenges, Choices and International Insight’ available on www.adviceni.net) indicate that the focus may be too heavily weighted in favour of moving people off benefits rather than firstly ensuring that people are adequately provided for on benefit. In our Welfare Reform paper we highlighted the plight of so-called floundering families in the USA:

“Welfare reform was successful because the US economy was good and because in-work supports – child care and health insurance – helped make work pay. With the downturn in the economy, problems with the US approach were highlighted as being the difficulty for welfare recipients to secure continuous employment (often a focus on ‘take the first job’ and not the ‘best job match’). There was also a very significant issue related to ‘floundering families’ – with a significant increase in single mother households without work and without access to welfare (number has almost doubled since 1990).”

19. We would argue that often the issue is not as straight forward as moving people into employment. There needs to be an acceptance that some people will need further assistance and support to gain the skills necessary to move into employment and that there should be a ‘job match’ between the job and the potential employee.

Comments – Support for working families on low incomes

20. The introduction of tax credits for working families has not been without significant problems and has pushed many families into debt and hardship due to creating overpayment situations. Advice NI has facilitated an online eConsultation on the issue of tax credits (http://www.adviceni.net/econsultation/default.asp) and produced a report with a number of recommendations to improve the situation. Whilst improvements have been made, there remains a significant amount of work to be done. In terms of families living in Northern Ireland, Advice NI believes that there should be local contact points within HMRC in order to resolve any problems that arise for tax credit claimants.

21. From a Northern Ireland perspective, Advice NI would summarise the ongoing tax credit issues as follows:

- Although the implementation of the Paymaster General’s Ministerial Statements in 2005 does seem to have had some effect, tax credit difficulties and in particular overpayments continue to occur. Advice NI believes that the tax credit system is generally difficult for most people to comprehend and that overpayments remain an inherent risk within the tax credit system.

- Advice NI continues to advocate that the system for disputing the recovery of tax credit needs to be overhauled. HMRC are the judge and jury in relation to making decisions on tax credit overpayments. There needs to be impartiality and independence in the handling of tax credit overpayment disputes. If not there may well be the potential for legal challenge under Human Rights legislation (right to a fair trial) but aside from the legalities the lack of independence contributes to a continuing lack of confidence in the process for disputing the recovery of tax credit overpayments.

- Advice NI is concerned that there is no local point of access to highlight NI-specific cases and issues. The centralisation of tax credit overpayments processing to GB and the removal of any ‘local point of access’ is frustrating for advisers and clients alike. Advice NI has representation on the Tax Credit Consultation Group but this forum is not ideal as meetings take place in London, the agenda is very full and it is not particularly responsive to the needs of NI advisers and clients.

- Advice NI believes that the communication / information flow between HMRC and Northern Ireland organisations could be improved. Generally speaking, Advice NI has had no little contact with HMRC on providing updates, news relating to tax credit developments and NI-specific statistics regarding uptake. This perceived communication vacuum may be a side-effect of the centralisation highlighted above, although Advice NI would acknowledge funding provided by HMRC in order to promote the take-up of tax credits in NI.

- Advice NI welcomes the funding streams made available by HMRC to reach out to the ‘hard to reach’ vulnerable customers and in particular people from Black and Minority Ethnic communities. However from a purely Northern Ireland position, Advice NI would underline HMRC’s equality duties under Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. This comment is made in the context of the ongoing debate around integration of people from BME communities, including migrant workers, and where responsibility lies in terms of the responsibilities of the state and responsibilities of the individual. Advice NI believes that care must be taken to ensure that a balance is struck and that HMRC continues to meet it’s statutory equality duties in terms of providing either direct or indirect information and support to people from BME communities.

22. Obviously the impact of making work pay would have a greater impact with a higher National Minimum Wage and such a step would not only make work more attractive, but might also directly reduce Government spending by reducing spending on tax credits, Housing Benefit and could indirectly reduce social security spending by making work a more attractive option.

23. In relation to child poverty, a move into paid employment can have a positive impact. However, where there are children in the household, the issue of affordable childcare provision is obviously important. It might be argued that where one partner is working the other partner could look after the children but this may not necessarily be possible: (i) in lone parent situations; (ii) the other partner may wish to move into employment; (iii) Government policy is now focussing on moving both benefit claimants and their partners into employment. The provision of affordable childcare is obviously an area where local initiatives could be developed – which could directly impact on the child poverty issue.

24. Linked to the childcare issue, there may be a real opportunity for individuals to set themselves up as childcare providers – from a ‘start your own business’ perspective. With this in mind, there should be a review of the process for registering childcare providers. A more straightforward process might have the two-fold impact of (i) increasing childcare provision and (ii) being a business opportunity for families on benefit.

Child Support Agency reforms

25. In relation to child maintenance, the introduction of the proposed Child Maintenance and Enforcement Commission (C-MEC) may provide the opportunity for children to become the focus of attention. In the past the issue of child maintenance was viewed with scepticism by both parents-with-care and non-resident parents. Parents-with-care on benefits saw their benefits reduce when they pursued child maintenance leading them to believe that the Government was only interested in reducing benefit expenditure rather than supporting children in any meaningful way. The new arrangements may address this issue but as yet there is no detail as regards any proposed maintenance disregard.

26. The issue of C-MEC delivery mechanisms raises issues similar to those around the centralisation of the tax credit system. Advice NI believes that local delivery mechanisms in terms of information provision, collection and debt recovery may maximise the effectiveness of the proposed Child Maintenance and Enforcement Commission.

27. As a general point in terms of consultation, Advice NI would ask OFMDFM to consider using the tried and tested Advice NI eConsultation service. Clients who have used the service to date include the Department for Social Development (Advice & Information strategy), Department for Social Development (Housing Affordability), the Consumer Council (Bank Charges) and the Oireachtas (Joint Committee on Communications, Marine & Natural Resources). The benefits of the service include:

- Maximise participation;

- Ongoing two-way communication;

- Comprehensive engagement;

- Embracing online technology;

Further information on the Advice NI eConsultation service can be found at

http://www.adviceni.net/econsultation/default.asp.

15 November 2007

[1] http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/en/docs/ni7_ACPR07.pdf

Written Submission by:

Barnardo’s NI

Introduction

Barnardo’s NI is the largest children’s charity in Northern Ireland. In addition to policy influencing, we also provide over 45 distinct services in NI, last year working with a substantial number of children and their families in communities across Northern Ireland. We work with disabled children, young people who are at risk of offending, children in care and families in need of support.

Barnardo’s vision is that the lives of all children and young people should be free from poverty, abuse and discrimination. We therefore welcome the opportunity to contribute to the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister’s Inquiry into Child Poverty.

1.0 The extent, intensity and impact of child poverty in Northern Ireland

While we recognise the need for further evidence in relation to the persistence of poverty in Northern Ireland, the extent and impact of child poverty throughout the UK have been well documented within a broad range of statistical and research publications[1]. Government must improve practices of producing and maintaining up-to-date data, however the considerable research activity in recent years has aimed to address the general lack of statistics and other data on child poverty in Northern Ireland. Therefore, rather than reiterate much of this information of which the Committee is no doubt aware, it is Barnardo’s intention for the purposes of the current inquiry to focus on three key areas in which we believe child poverty should be tackled more effectively and where there is a significant impact on children and young people.

1.1 Early Years

The disparity in educational attainment throughout primary and secondary schooling between children and young people with more affluent status compared to those from poorer backgrounds has been clearly demonstrated in research carried out by the Department of Education[2]. However this educational disadvantage is also apparent from an early age in that pre-school children with a lower economic status have less cognitive and behavioural abilities[3] than pre-school children from higher socio-economic backgrounds[4].

Considering the links between poor education and unemployment with poverty, Barnardos believes that in order to effectively address social inequality it is vital that government supports families and agencies working with pre-school children by demonstrating an increased commitment to early years intervention. This is even more important given that social and emotional skills learned between birth and the age of five years affects subsequent performance in both the school and workplace[5].

Furthermore, the key finding from brain research is that the brain is uniquely constructed to benefit from experience and from positive care giving during the first years of life[6]. Significantly, the brain develops earlier than the rest of the body;

- 50% of its’ adult weight in the first six months;

- 75% of its’ adult weight by age two and half years;

- 90% of its’ adult weight by age five years.

By age three the brain has formed 1,000 trillion connections; about twice as many as adults have.

Early experience determines how the neural circuits in the brain are connected. (Bertenthal and Campos, 1987) and children who are played with, spoken to and allowed to explore stimulating surroundings are more likely to develop improved neural connections which aid later learning (Kurr-Morse and Wiley, 1997)[7]. These recent findings from brain research emphasise how crucial the first five years of life are. In this time neural pathways are formed and disposition toward learning is established. French and Murphy (2005) comment:

‘Sylva (1993) having reviewed the evidence about the impact of early learning on children’s later development, concluded that the impact of early education is found in all social groups but is strongest in children from disadvantaged backgrounds’[8].

It is therefore Barnardo’s view that rather than waiting for children to reach school age, it is essential that, from birth, children receive the best possible start in life. Indeed by investing financial resources in programs for very young children, including interventions such as the Perry Preschool program, research suggests that society benefits in the long term through an increase in skilled workers, and a reduction in crime, violent activity and poverty[9]. The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study, for example, published its research spanning 40 years in November 2004 in which the measured benefits of the programme are highly significant[10]. This long term study shows the effects of a high quality early years care and education programme with children and their parents on low income three and four year old children. At age 40, adults who had participated in the High/Scope programme were shown to have higher earnings, be more likely to stay in employment, have higher academic achievement and to have committed fewer crimes than those in the non-programme group. Although schools and teachers are important, early and ongoing engagement with parents is the key to successful interventions and subsequent changes in society[11].

Government must also consider the important role of play for children’s social, emotional and physical development, especially in their very early years. Through our many services, Barnardos continually provides play opportunities and promotes the value of play in many areas, for example in early years settings, a range of parent education and parent support services including parents from minority ethnic backgrounds, parents in prison and school aged and other young mothers, and for children with disabilities and complex health care needs. Unfortunately, current play and leisure provision for children and young people in Northern Ireland is generally inadequate and often inaccessible, particularly for children experiencing poverty[12].

Good Practice

At Barnardos, we know that young children learn from direct experience. In order to affect change for children we need to support parents in the parenting role. It is important, however, that alongside working with parents, every effort is made to ensure young children do not lose out on positive experiences at this crucial stage in their development. Barnardo’s Northern Ireland has been providing services to the youngest and most disadvantaged members of our society for over thirty years. These services provide a wide range of experiences for young children.

High/Scope Approach

Throughout all early years work in Barnardo’s Northern Ireland the High/Scope Approach discussed above in relation to Early Years is implemented. Using this Approach ensures positive outcomes for children both in the short and long term. In addition to parents, High/Scope provides valuable training for early years teachers, pre-school practitioners, Sure Start projects, those working with under-threes, foster carers, and childminders.

Barnardo’s believes that the High/Scope approach is a valuable tool in helping combat poverty and promoting social inclusion in the most disadvantaged communities of Northern Ireland and would recommend its implementation on a broader scale. The following two examples give an indication of the current range of early years work in Barnardo’s Northern Ireland and we would warmly welcome Committee representatives to visit these and any of our other services.

Travellers Pre –school

Barnardo’s NI has long acknowledged the particular difficulties experienced by the Traveller community, including poor living conditions, inadequate housing, long term unemployment, poor health and poor educational attainment. We have provided an early years service to the Traveller community in Belfast since 1990 of which the main aim of the Traveller’s Pre-School is to promote the inclusion and integration of Traveller children into mainstream education. As a formal recognition of the high quality service being delivered to children and their families within the Traveller community, Traveller’s Pre-School has recently achieved High/Scope Accreditation from the High/Scope Ireland Institute, the first early years service in Barnardos NI to receive this award.

Parent & Infant Project (PIP)

The PIP model was built on key evidence about childhood development that linked factors such as the early development of language, development of social and personal skills and infant mental health. The overall aims of the service are to enable young children to achieve their potential according to their abilities and develop socially, emotionally, physically and intellectually; and to establish an environment where parents will be facilitated in recognising and meeting the needs of their children. With a central ethos of early intervention, the main objectives of this outreach based project are to promote and support very early learning in children aged 0-3 years; to offer parent support and education; to help parents to recognise and meet the needs of their children; to increase parents’ confidence in their own knowledge; and to improve the self esteem of the adult and child through enabling and valuing the proficiency of both.

1.2 Disability

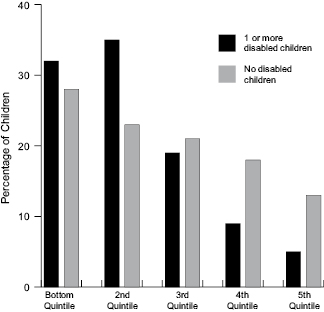

In Northern Ireland, 21% of adults have at least one disability and 6% of children are affected by a disability, of which almost 4% are living with two or more disabilities[13]. Current poverty statistics, which underestimate levels of poverty in households affected by disability, indicate that over a million children living in poverty in the UK are affected by disability while a quarter of all poor children have a disabled parent[14].

There is evidence to suggest that families affected by a disability, whether of a parent or child, are at greater than average risk of persistent poverty. Research shows that disabled children and their families in the UK experience particularly high levels of economic and social disadvantage[15]. It is estimated in the region of 55% of families with a disabled child are either living at or on the margins of poverty and have more chance of living in poverty than other disadvantaged social groups, including lone parent families[16]. The risk of poverty is especially high for the half a million children who live in households that contain both disabled adults and disabled children[17].

Incomes in households with disabled children are likely to be low because these families experience considerable additional costs, face multiple barriers to employment, and problems accessing disability benefits. For example, although the cost of bringing up a disabled child is three times as much as for a non-disabled child, parents in such families are less likely to work and when they do they are more likely to be in low-paid employment. Inaccessible services and poor service provision for families affected by disability compounds problems on a daily basis, and generates high levels of stress and ill-health[18]. The situation is often particularly serious in families affected by disability if it is also a lone parent household and/or there are three or more children.

These are all issues which need to be urgently addressed, especially considering the impacts on child poverty in Northern Ireland which has the highest levels of households with disabled people in the UK. Better administrative processes and increased take up of disability living allowance has been identified as just one measure to improve the lives of disabled children and help reduce child poverty[19]. If the Government wants to ensure that targets to eradicate child poverty are met then it is essential in Barnardo’s view that in addition to greater access to preventative and support services, more must be done to ensure that disabled children and those caring for them receive the disability benefits to which they are entitled. It is also essential that parents who so often act as full-time carers for their disabled children receive appropriate support that enables them to access well-paid and permanent employment.

Disabled children themselves face significant barriers to education, training and employment without the necessary preventative and support services. Recent research on education and employment amongst disabled young people found that despite similar aspirations, the experience of disabled and non-disabled young people diverged sharply in early adulthood[20]. Analysis of the data from studies of children born in 1970 and in the early 1980s revealed that three-fifths of non-disabled young people got the education or training place or job they wanted after finishing compulsory education, whereas just over half of disabled youngsters said the same. As they got older the gap between the proportion of disabled and non-disabled young people out of work widened:

- at age 16/17, disabled young people were about twice as likely as non-disabled to be out of work or ‘doing something else’ (13 per cent compared with 7 per cent);

- by age 18/19, disabled young people were nearly three times as likely to be unemployed or ‘doing something else’ (25 per cent compared with 9 per cent);

- at age 26, young people who were disabled at both age 16 and age 26 were nearly four times as likely to be unemployed or involuntarily out of work than young people who were disabled at neither age (13.8 per cent compared with 3.7 per cent).

Recommendations arising from this research include a focus on transforming the actual opportunities available to disabled young people, for example, through ensuring continuity of support (including funding, equipment and personnel), especially in the transition from secondary to further education; opportunities to return to education, focusing on acquiring higher qualifications, not just basic skills; and work placements related to each young person’s expressed interests.

1.3 Employment and Learning

Young people making the transition from education to employment now face many more challenges and obstacles than ever before mainly as a result of changes in traditional family structures and a rapidly changing labour market. Those young people who do not stay on at school or in further education or training have fewer opportunities than in previous years.

The term ‘NEET’ is now used to describe young people aged between 16 and 18 (inclusive) who are not in education, employment or training, however Barnardo’s discusses this issue as being relevant to young people aged between 16 and 21 years of age. Many of the characteristics associated with poverty are also associated with young people referred to as NEET. These typically include poor educational attainment, persistent truancy, teenage pregnancy, use of drugs and alcohol, looked after children, disability, mental health issues and crime and anti-social behaviour[21]. The proportion of NEETS has increased from 154,000 in 1997 to 206,000 in 2006[22]. In England, 7% of all 16 year olds are NEET, rising to 11% of 16 year olds from the lowest social groups, 13% amongst those with a disability, 22% amongst those excluded from school, 32% among persistent truants and 74% amongst teenage mothers[23]. In 2005, 6.3% of 16-24 year olds in Northern Ireland were classified as being unemployed, however the percentage of young people classified as NEET is estimated as being twice as high[24].

Barnardo’s believes that the massive potential amongst young people who are NEETS is in danger of being overlooked if those responsible for the education and welfare system do not address what is becoming an increasing issue of concern. The Westminster government has recently revealed plans to raise the school leaving age to 18, although there is no immediate intention to introduce this in Northern Ireland. While we can see the obvious benefits in ensuring education, training or apprenticeship for many NEETS, this will only work in practice if it is actually meeting each individual’s need and that other mechanisms are also put in place for those young people that actually want to, or cannot afford not to, go out to work at 16. For various reasons, not all young people within this age group are able to live in a stable and secure family environment and we would have concerns about the poverty implications if they were unable to enter formal employment until the age of eighteen.

Having NEET status not only impacts on young people’s life chances but from a public policy perspective there are also a range of social and financial implications. Young people who are NEET are at risk of poverty and social inclusion but it has also been suggested that being NEET,

‘..may also perpetuate a worklessness culture that can be passed onto future generations of young people and result in NEET status being reinforced in families and communities across generations’[25].

It is therefore crucial that effective strategies are in place in Northern Ireland to ensure young people are in appropriate employment or learning. This age group should also be given priority in the ‘Lifetime Opportunities’ Anti-poverty Strategy, with a very specific focus on targeting those aged between 16-21 years.

As highlighted in the Strategy, employment for people of working age is the best route out of poverty. However, given the high levels of low pay in Northern Ireland alongside the lack of affordable housing, childcare and fuel for heating, it is also important to consider that an increasing number of people experience ‘in-work’ poverty. This is of particular relevance in relation to younger people aged between 16 and 21 years old who are more likely to earn less and for whom the minimum wage is lower than for adults. While we welcome the minimum wage in principle, Barnardo’s believes that this must be regularly reviewed and increased in order to ensure income protection for young people. In our view, it is discriminatory to pay younger people between 16 and 21 years lower wages for doing the same job as someone older, simply on the basis of age. Research has also highlighted the inadequate level of welfare benefits for young people and accessible information in relation to these, and also the need for more effective training of frontline benefits staff[26].

2.0 Consider the approach taken when formulating the current strategy including the extent of the engagement with key stakeholders

Barnardos does not wish to comment other than to welcome the fact that following a fairly lengthy process, the current strategy has been developed into a much more child focused document. However, we have outlined our main ongoing concerns and recommendations throughout this paper.

3.0 Assess whether the existing strategy is capable of delivering the key targets for 2010 and 2020

While Barnardos welcomes the commitment in the Strategy to eliminate poverty, we are concerned that in its current format it will be unable to deliver the key targets within the specified timeframes, and that the targets themselves are limited in their scope. The absence of targets that are generally not Strategic, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant and Timely (SMART) is a notable gap.

We would refer you, for example, to the three areas we outlined at Point 1 in relation to Early Years, Disability and Employment/Learning, which we believe need to be given greater priority within the Strategy if the main target of ending child poverty by 2020 is to be a realistic one.

(1) EARLY YEARS – For example, we suggest that targets and indicators are reworked to include emphasis on universal access to high-quality, creative and innovative early years programmes and pre-school provision; and to include early and ongoing engagement with parents; positive parenting etc.

(2) DISABILITY - With regards to our previous points on disability, we suggest for example, the development of targets and indicators that address welfare benefits access, service provision and the widening gaps between disabled and non-disabled young people’s participation in employment as they move into early adulthood

(3) EMPLOYMENT AND LEARNING – For example, we suggest the development of targets and indicators specific to young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) and aged between 16 and 21 years of age; also to include preventative and support structures - potential young people NEET identified before they leave school; regular review of attendance, behaviour and attainment; monitoring of ‘at-risk’ pupils, for example, looked after children; extended schools activities; counselling and home support services; family learning and parent contact work; use of specialist outreach teams; use of social work and youth and community work staff.

4.0 Examine whether the implementation mechanisms, resources and monitoring arrangements currently in place are adequate to ensure delivery of the key actions/ targets.

Also with reference to our previous points, we have some concerns in relation to the practical and effective implementation of the Strategy. Without appropriately developed targets, action plans or agreed financial resources it is difficult at this stage to assess the adequacy of the implementation mechanisms, resources and monitoring arrangements.

5.0 Identify and analyse relevant experience elsewhere in terms of policy interventions and programmes

Considering that the UK figured seventh from the bottom of a league table comparing child poverty across 26 wealthy nations[27], Barnardo’s would strongly recommend that cognisance is paid to the experiences of other nations, including their child poverty national strategies, social policies and other interventions[28].

We also suggest continued monitoring and awareness of how child poverty is being tackled by the Welsh and Scottish governments. Finally, it would be useful to keep appraised of ongoing research in the relevant areas, some of which is cited in the footnotes of this paper, with particular attention paid to findings and recommendations on ‘What Works’ and areas of ‘Good Practice’.

6.0 Consider what further actions could be taken to tackle child poverty with particular focus on those that would be deliverable by the devolved administration.

There are clearly many other areas where action to tackle child poverty is required both outside and inter-related to those that we have chosen to discuss here. We enclose for your information our recent child poverty briefing, ‘It doesn’t happen here: the reality of child poverty in Northern Ireland’, which provides a concise overview of the issues and a number of key recommendations for action by the Northern Ireland Executive.

Concluding Comments

Barnardos welcomes the chance to contribute to the OFMDFM Committee inquiry into child poverty. We would also like to take this opportunity to extend a formal invitation to Committee representatives to visit Barnardo’s services, particularly those relevant to our work in Early Years.

20 November 2007

[1] For example, statistics recently published in a Households Below Average Income report suggest that almost one in three children in Northern Ireland are living in poverty – HBAI 1994/5-2005/6, 18th Edition. See also, Barnardo’s NI (2007), ‘It Doesn’t Happen Here: The Reality of Poverty in Northern Ireland’, Barnardo’s; E. McLaughlin and M. Monteith (2006) ‘Child and Family Poverty in NI’, OFMDFM, NI; and Save The Children (2006) ‘Under the Radar: Severe Child Poverty in the UK’.

[2] www.deni.gov.uk/statisticsandresearch; for example T. Gallagher and A. Smith (2000), ‘Research into the effects of the selective system of secondary education in Northern Ireland; A. Sutherland and N. Purdy (2006), ‘Attitudes of the Socially Disadvantaged towards Education in Northern Ireland’

[3] Common definitions of cognitive abilities refer to thinking and problem-solving skills, e.g. ‘the process of being aware, knowing, thinking, learning and judging’ MedicineNet.Com

[4] E. Melhuish et al (2006), ‘Effective Pre-School Provision in Northern Ireland (EPPNI)’, DENI, Report No.41

[5] James J Heckman and Dimitriy V Masterov (2004), ‘The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children’, Committee for Economic Development

[6] G. French and P. Murphy (2005), ‘Once in a Lifetime: Early Care and Education for Children from Birth to Three’ Dublin. Barnardo’s

[7] Cited in French and Murphy, ibid

[8] Ibid, p.20

[9] L. Schweinhart et al (2005), ‘Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40’, High/Scope Educational Research Foundation; Heckman, op cit n.4; and Alan Sinclair (2007), ‘0-5: How Small Children Make a Big Difference’, Provocation Series, Vol. 3, No.1, The Work Foundation

[10] L. Schweinhart et al, ibid

[11] Sinclair, op cit n.8

[12] U. Kilkelly et al. (2004), ‘Children’s Rights in Northern Ireland’, NICCY

[13] NISRA (2007), ‘The Prevalence of Disability and Activity Limitations amongst adults and children living in private households in NI’, July 2007, Bulletin 1

[14] Gabrielle Preston with Mark Robertson (2006), ‘Out of Reach: Benefits for Disabled Children’, Child Poverty Action Group

[15] Gabrielle Preston with Mark Robertson (2006), ‘Out of Reach: Benefits for Disabled Children’, Child Poverty Action Group; D. Gordon, R. Parker, F. Loughran and P. Heslop, Disabled Children in Britain: A Re-analysis of the OPCS Disability Surveys., London, TSO, 2000; OPCS Surveys of disability in Great Britain Report 5 (1989): ‘The financial circumstances of families with disabled children living in private households’, www.statistics.gov.uk.

[16] Gordon et al, ibid

[17] Preston and Robertson, op cit, n.14

[18] ibid

[19] ibid

[20] Tania Burchardt (2005) ‘The education and employment of disabled young people: Frustrated ambition’, The Policy Press in association with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

[21] Research as Evidence (2007), ‘What works in preventing and re-engaging young people NEET in London’, Greater London Authority

[22] Department for Children, Schools and Families, and Innovation, Universities and Skills

[23] Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (2005) ‘NEET Design Review Presentation’, PMDU, London, cited op cit, n.20

[24] London School of Economics (2007), ‘The Cost of Exclusion: Counting the cost of youth disadvantage in the UK’, Princes Trust.

[25] Op cit, note 20, p.7

[26] U. Kilkelly et al. op cit, n.11

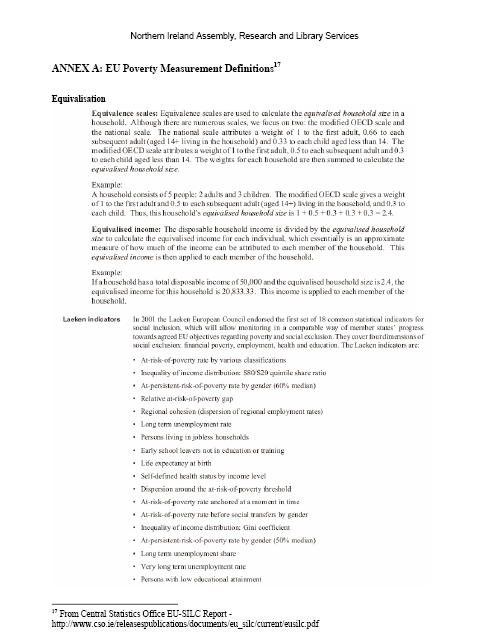

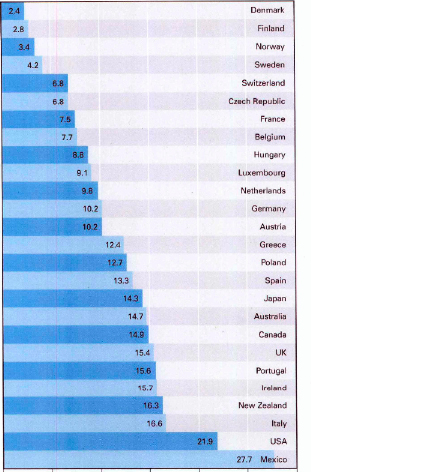

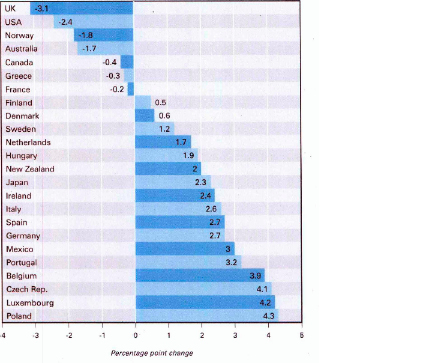

[27] Innocenti Research Centre, ‘Child Poverty in Rich Countries 2005’, UNICEF

[28] Also refer to Mark Greenberg (2007), ‘From Poverty to Prosperity: A National Strategy to Cut Poverty in Half’, Center for Amercian Progress

Written Submission by:

Belfast Health Action Zone

Background

The Belfast Health Action Zone (HAZ) is a partnership of public, private, voluntary and community sector organisations working together to tackle inequalities in health and broader social exclusion. The HAZ functions by:

- Developing effective practice

- Influencing and changing ‘mainstream practice’

- Creating links and using practice to influence government policy

The HAZ experience

The HAZ focuses on a broad social model of health based on the twin pillars of partnership and participation. Whilst the title is ‘Health’ Action Zone the practice has been to take an inclusive approach to addressing areas of need. HAZ has sought to focus efforts on issues or settings of greatest need where collaboration can bring greatest benefit (development pathways). Each of these work programmes or ‘development pathways’ is led by a different partner within the HAZ Partnership but engages a wide range of other organisations in the process. Examples relevant to Child Poverty include:

- Developing an integrated approach to tackling the accommodation needs, prejudice and inequality experienced by the Irish Traveller community (led by the NI Housing Executive)

- Changing how services can work together to improve health and education outcomes e.g. Communities in Schools/Extended Schools (led by Belfast Education and Library Board and school principals)

- Integrating services for children and young people (led by area Partnership Boards, communities and schools)

- Contributing new knowledge and learning e.g. labour market analysis, evaluation, needs analysis (led by different partners)

- Creating new approaches to addressing the needs of long term unemployed people and their families e.g. Futures (led by the former North & West Belfast Health and Social Services Trust), and the Employability Access Project (led by North Belfast Partnership Board)

Five Major Challenges

HAZ experience suggests that there is still much work to be done to effectively tackle inequalities in health and that the health and wellbeing of those who are most disadvantaged in Belfast is characterised by five common features:

- A lack of aspiration

- High levels of relative poverty

- Significant underachievement

- Continuing fear for local safety

- Ongoing lack of good relations between communities

Accordingly it is suggested that concerted action is required with commonly agreed goals for the next ten years so we might work toward:

1. Aspiration: Children in disadvantaged areas of Belfast can be shown to exceed their expectations of educational achievement in spite of disadvantage; and, communities’ aspirations can be shown to be more positive.

2. Poverty: A measure of relative poverty is adopted and used to set targets to ensure that people in disadvantaged areas of Belfast can be shown to suffer no greater disadvantage than across Northern Ireland as a whole.

3. Achievement: An increase in the number of school leavers with qualifications in all disadvantaged areas of Belfast can be demonstrated, to equal the average for Northern Ireland as a whole.

4. Safety: Fear of crime can be shown to be significantly reduced.

5. Good Relations: Greater respect and tolerance can be demonstrated within and between communities taking account of the changing nature of the population and including ethnic minority groupings.

Each of these goals will need clear targets. It is recognised that targets can be somewhat narrow and that these measures need to be supplemented by other broader indicators. Shorter-term milestones and indicators for each of these challenges need to be developed and agreed over the coming period.

HAZ suggests that if progress is made in each of these areas there will be considerable improvement in health and wellbeing and a reduction in the wider inequalities gap including poverty.

How will this be achieved?

The experience of HAZ has pointed to the centrality of employment, educational achievement, health and wellbeing and community engagement. It is proposed that work should continue to:

- Seek to align individual partners’ plans and contribution to this approach

- Ask all agencies to align their policies, procedures, practice, investments and plans to help to achieve the agreed targets and goals

- Redesign the way services are delivered

- Expand and develop contracts between the public sector, private sector and community organisations which make a commitment to enhancing employability and employment opportunities

HAZ would also strongly suggest to the Committee that agreed goals to which all Government Departments and their agents are committed to delivering is probably the single most important action that Government could consider.

HAZ recent analysis of need has pointed to the centrality of education as a means of impacting on poverty (copy attached for your ease of reference).

What would improvement look like?

Clearly much work is already underway, however it is also true that we could accelerate effective practice. Improving the impact of resources, money and people could be further demonstrated in a number of areas.

- Enhanced Emphasis on Community Engagement.

One of the major problems in addressing inequalities is engaging those people who are hardest to reach, often also those in greatest need. Strategies for community empowerment have helped give a voice to local communities that feel threatened, vulnerable or disadvantaged and this capacity building should continue to be supported.

Neighbourhood Renewal and Strategic Neighbourhood Action Planning (SNAP) offer a key approach not just to listen to local people but to engage and build up detailed profiles of local needs and aspirations. These initiatives could be drawn together to become more effective.

- Development of New Types of Facilities.

The idea of One Stop Shops can be expanded. Models such as the new Health and Wellbeing Centres which link health and social services with library and leisure services could be enhanced to embrace housing, educational support, welfare rights advice, access to specialist services and so forth. In the future, planning any new public facility could consider multiple users rather than sectoral interests e.g. schools could also incorporate community access to leisure services and health services.

- Development of Integrated Services

A radical shift in how services are developed and delivered as part of a truly integrated process could be expanded so that:

- there is real engagement of the community and service users in the design and delivery of services to ensure their relevance

- there is no duplication of assessment procedures

- services are delivered by multi agency, multi disciplinary teams

- integrated planning happens on both a strategic and local basis

- agencies agree, share and work toward common goals

- there is common (but still protected) information sharing and database

Achieving these aspirations will also require a re-think on how Government departments operate and coordinate with each other as well as a requirement on all agencies to link their working practices and processes with each other.

- A new approach to delivering a more appropriate economic infrastructure.

Although confidence in Belfast is growing and there is an increase in small and medium sized businesses, the economic underpinning that is required to tackle disadvantage is still a long way from being in place.

Although there may be an improving economic climate in the city it is not impacting on those who are suffering the greatest disadvantage. The key to tackling economic change may be a combination of aspiration and education so that citizens can take advantage of the opportunities available in the future.

- A requirement to adopt holistic approaches.

There is a need to develop coordinated approaches for communities and, in particular, families experiencing difficulty. For example, some people face multiple problems such as lack of education and life skills, low self esteem, disjointed personal relationships, lack of opportunity, lack of information and have been affected by the long-term impact of the ‘troubles’. Comprehensive, locally based holistic strategies taking all of these issues into account offer a more effective means of support.

Possible Priorities for Next Phase HAZ Work

A number of priorities are currently under consideration which will build on existing work and will include:

Children and Young People

1. Use schools and communities as settings for development of new services and approaches together with the community and other partners.

2. Strengthen the development of integrated services for children and young people with the lessons examined for relevance to other issues.

Communities and Neighbourhoods

1. Develop an integrated approach to meeting the needs of ethnic minority groups including Travellers.

2. Expand and develop Neighbourhood approaches to local planning and development working closely with local communities.

3. Develop new approaches to families or communities at particular risk, building on the integrated services for children and young people initiative.

4. Seek to build community relations by working with communities and partner organisations to advance joint understanding and practice at local level.

Thematic Approaches

1. Adopt a coordinated approach to thematic areas of work such as mental health (including suicide prevention), sexual health and wellbeing, and drugs and alcohol.

2. Support efforts to develop a coordinated approach to community safety and fear of crime.

Employment & Employability

1. Enhance opportunities for public service providers to address employability through increased access to employment schemes.

There is now a comprehensive consultation process underway to engage in debate about the final shape of any future priorities for the HAZ.

A way forward

We believe that there has never been a more appropriate time to address the challenge of inequality in Belfast - including the challenge of poverty. Reform of the public sector and local government, together with new local political governance, presents an unparalleled opportunity when all of the key players, embarking on a change process, can embrace a radical new approach. Leadership will be central at such an exciting time.

Belfast is a great city - it can be an even better place to live. It has marvellous natural resources of which the greatest is its people. HAZ has had nine years of experience of practice in this endeavour. Some of this has been successful, but a great deal is still to be done. Child poverty, like inequality is a complex issue with multiple contributing factors. The answer lies in a holistic, joined up approach with agreed targets across Government monitoring to chart progress over time, a clear accountability mechanism, and integrated delivery of programmes on the ground.

23 November 2007

Health Action Zone Council Members

Belfast City Council |

Mr Richard Black OBE |

Independent Chairperson |

Belfast City Council |

Ms Marie Therese McGivern |

Director of Development |

Belfast City Council |

Ms Suzanne Wylie |

Head of Environmental Health |

Belfast Education & Library Board |

Mr David Cargo |

Chief Executive |

Belfast Health & Social Care Trust |

Mr William McKee CBE |

Chief Executive |

Belfast Metropolitan College |

Ms Joanne Jones |

Principal Lecturer |

Belfast Metropolitan College |

Mr Brian Turtle |

Director |

Belfast Regeneration Office |

Ms Elaine Wilkinson |

Director |

Business in the Community |

Mr John McGregor |

Director |

Council for Catholic Maintained Schools |

Mr Jim Clarke |

Deputy Chief Executive |

Department for Employment and Learning |

Ms Harriet Ferguson |

Regional Manager, Belfast Area |

Department for Social Development |

Mr Declan McGeown |

Director, North Belfast Community Action Unit |

East Belfast Partnership |

Ms Maggie Andrews |

Partnership Manager |

EHSSB/ Health & Social Care Authority |

Ms Anne Lynch |

Director of Planning |

Greater Shankill Partnership |

Mr Jackie Redpath |

Chief Executive |

North Belfast Partnership Board |

Mr Murdo Murray |

Chief Executive |

Northern Ireland Housing Executive |

Ms Mary McDonnell |

Housing & Health Coordinator |

Probation Board for Northern Ireland |

Mr Andrew Rooke |

Assistant Chief Officer |

Queen’s University, Belfast |

Dr Mike Morrissey |

Researcher |

Social Security Agency |

Mr Mervyn Adair |

Director of Operations |

South Belfast Partnership Board |

Ms Anne McAleese |

Chief Executive |

University of Ulster |

Vacant |

Vacant |

West Belfast Partnership Board |

Mr Noel Rooney |

Chief Executive |

Written Submission by:

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust

Children’s Social Services

Relative poverty is associated with lack of choice and opportunity. Children in households which experience persistent or intermittent episodes of relative poverty face substantial barriers to a realisation of their potential in both social and economic terms.

This is particularly evidenced in the fields of education and health. As a consequence of their material disadvantage, children face major potential. All the key educational indicators evidence the link between relative poverty and poor outcomes.

As a result, an intergenerational disinvestment in the value of education is woven into the value-base of individual families and given expression in a cultural marginalizing of educational achievement across communities.

While Children from poor families do achieve educationally, their numbers relative to more affluent sectors of the population are significantly small.

Education in this context incorporates both academic and non-academic attainments. The hierarchical infrastructure underpinning selection has critically impacted upon the status of vocational education. Children from poor families are doubly disadvantaged. Their potential is not realised within an educational framework which promotes academic excellence and undervalues vocational skills.

As society becomes increasingly individualised and success calibrated in terms of material measures, the cycle of advantage and status is reinforced.

For poor children ambition is subsidiary to need. Children internalise the importance of pragmatism and shape their horizons within parameters which are constrained by the imperatives of little money. Within communities in which the relatively poor merge with more affluent neighbours and in which corporate values and experiences are no longer shared, poor children experience the realities of difference and attendant detachment.

The sense of failure experienced by cohorts of children in relative poverty merges with disengagement and marginalisation for those without sufficient resilience or whose individual family circumstances compound a predisposing vulnerability.

In those communities which are universally disadvantaged their perception of exclusion is confirmed in structural deprivation which contributes to immobilising apathy, fatalism and powerlessness.

The links between dysfunctional parenting and relative poverty are complex and not transparent. While relative poverty compounds individual disadvantage and undermines coping resources and resilience, there is no absolute connectivity.

Relatively poor parents are neither dysfunctional nor inadequate. They have ambition and hopes for their children but are unable to provide financial supports or to access the informal social and employment networks which provide mediating pathways and opportunities for more affluent families.

Poor children are neither deviant nor failing. Their circumstances in many instances inhibit their potential and ambition.

Relative poverty erodes choice, inhibits capacity for innovation and initiative undermines resilience and compromises personal responsibility and accountability.

Services to support those in relative poverty need to promote user involvement, resilience, esteem self-worth, personal responsibility, empowerment and choice. They should be targeted while non-stigmatising, encouraging education and training and maximising community and informal networks.

Maternity Services

The Royal Jubilee (RJMS) and Mater Maternity Services are part of the Belfast HSC Trust. The RJMS provides tertiary referral obstetric, gynaecology and neonatal services for the population of Northern Ireland and, with the Mater Maternity Unit, a full range of services for the local population of Belfast including a fully integrated maternity service. We welcome the opportunity to contribute to this consultation process.

For the majority of women in Northern Ireland pregnancy and childbirth are normal life events. The impact of poverty however on women during their pregnancy is well documented with the associated detrimental impact on outcomes for both the mother and baby. The incidence of teenage pregnancy is higher in this group. Women living in disadvantaged or minority groups are less likely to access maternity services early, or maintain contact throughout their pregnancies and subsequently this impacts on the ability of the service to respond to their needs. This may be further complicated by the raising numbers of families moving to Northern Ireland from other countries e.g. Eastern Europeans, with a limited command of the English language and a poor knowledge of how to access services.

The health of the mother herself may have been adversely affected during her own life, from conception through to adulthood. Poor housing, poor diet, increased incidence of smoking, drugs and alcohol abuse all contribute to increase in premature labour, and higher than average perinatal and infant mortality rates. Increasing numbers of women accessing services are known to social services. Domestic violence and disruptive relationships are also linked to the spiral of poverty. Mental health problems are often manifested during pregnancy or following birth.

The levels of breastfeeding among women from socially disadvantaged groups are lower. The outcomes for their own and their children’s health are worse than for the population as a whole.

Midwives, doctors and other professionals working in maternity services have to consider and plan for the effects these problems may have on the woman’s ability to care for her baby. A Multidisciplinary team approach, during the antenatal and postnatal periods is essential to provide basic care and support for the mother and family. Accurate and prompt communication is a key factor in the provision of maternity services with emphasis on the needs of the vulnerable and disadvantaged women with a clearly documented care plan, which should be developed with the woman.

Several of the maternity units in Northern Ireland have established Maternity Services Liaison Committees (MSLCs) where service commissioners, providers and users work together to plan a comprehensive range of services that will meet the needs of women in their area. These partnerships include other organisations and voluntary groups including for example, Sure Start, Women’s Aid, Northern Ireland Council for Ethnic Minorities (NICEM), Tiny Life, National Childbirth Trust, the Stillbirth & Neonatal Death Society (SANDS), the Twins and Multiple Birth Association (TAMBA), the Miscarriage Association, the Association for the Improvement in Maternity Services (AIMS) and others. It is only through ensuring there is real multi agency working that the risks can be mitigated.

Children with Disability

The Bamford Review clearly highlights and illustrates the correlation between social deprivation and the prevalence of mental health difficulties. People with mental health problems consistently identify personal finances as a major source of difficulty and distress. Amongst the issues highlighted are the impact of poverty and social exclusion on mental health and well being and the ways in which stigma, discrimination and the impairments experienced by people including children and young people with mental health problems impact on access to and management of personal finances.

The Review also highlights that those living on incomes below the average wage are twice as likely to develop mental illness as those on average or higher incomes. Surveys of adults and children with mental health problems confirm that the majority of individuals live in households with low incomes.

As Northern Ireland has a higher level of socio economic deprivation there is evidence which the Trust’s experience would confirm that the prevalence of mental health problems and disorders in children and young people is greater than in other parts of the United Kingdom. There is also clear evidence that children with a physical disability are at a significantly higher risk of developing mental health problems.

The experience of professional staff working within the Trust providing Mental Health and Disability Services to children and adolescents also endorses the evidence that such problems and disorders are clearly linked to deprivation and poverty. Such children are often exposed to a wide range of problems associated with social and educational disadvantage and experience would suggest that Looked After Children and abused children are particularly vulnerable. This is borne out by caseloads within Child & Adolescent Mental Health and Disability Services.

It is also evident that young people requiring Mental Health or Disability Services can experience varying degrees of social exclusion and often do not enjoy the same opportunities as others in relation to services such as education, training, employment and resources. This, from our experience, can perpetuate the cycle of deprivation and poverty and its consequences.

Child Health

In relation to child health it is essential we raise awareness of child poverty amongst professionals and ensure they have adequate skills to recognise signs of poverty and to signpost families to assistance. This would span all areas of acute and community child health and all professionals therein. We have an opportunity to highlight concerns about families within our daily business to ensure children reach their development potential unhindered by poverty.

We don’t only look at the health issues but the holistic issues of child development within a social context, and this is all our responsibility not social services alone .Our service group in the Belfast Trust will promote this as a core principle.

15 November 2007

Written Submission by:

Children in Northern Ireland

1. Summary

- The targets to end child poverty in the draft PfG and draft PSA Framework must be backed by a commitment of significant resources to enable actions and activities which can begin the process of tackling child poverty.

- The NICCY Research on Public Expenditure on Children and Young People[1] (2007) highlighted significant disparity in spend on children’s personal social services. The DHSSPS must explicitly demonstrate in its final budget outcome the steps which it is taking to address the level of underspend on children’s personal social services in NI.

- The Executive’s commitment to tackling child poverty would be fundamentally undermined should any vital children and young services disappear post March 2008. The Committee must act now to protect, maintain and further development existing early intervention and prevention initiatives which are already showing positive indications of their contribution to tackling child poverty in NI.

- The OFMDFM Junior Ministers with responsibility for children’s issues must actively ‘champion’ the government commitment to end child poverty. There is a real need for a high profile public awareness raising and education campaign to highlight the reality of child poverty in NI.

- The Ministerial Sub-Committee for Children should be re-convened as expediently as possible to consider and agree on the cross-government action that is needed to meet the targets set in the draft PfG.

- The Committee should urge the Junior Ministers to lobby their Executive colleagues to set up a cross cutting ring-fenced package that would allow for the development and piloting of creative, innovative evidence based approaches to tackling child poverty. Successful approaches should then be mainstreamed across departmental baseline budgets.

- 29% or 122,000 children live in poverty in NI. 10% of children in NI or 44,000 children live in severe poverty.

- The largest gap in information about child poverty is the voice of children themselves. The Participation Network is a vital resource in supporting and enabling Government and its agencies to effectively engage with children and young people experiencing poverty when taking forward work to advance the development and implementation of a comprehensive strategic approach to tackling child poverty.

- A strategic approach to tackling child poverty must include additional support for poor children and families to access mainstream universal services and targeted action directed toward groups of children whose experience of marginalisation makes them particularly vulnerable to experiencing poverty.

- The link between child poverty levels and the absence of accessible, quality, affordable and age appropriate childcare must be addressed. The Committee should use its influence to ensure that a single department takes responsibility for all aspects of childcare.

- Monies (£11.4m) made available for disabled children’s services under the Barnett Formula must be ring-fenced and an inquiry held to ensure that these monies are spent to best effect in meeting the current gaps in provision for disabled children.

2. Introduction

2a. Children in Northern Ireland (CiNI) is the regional umbrella body for the children’s sector in Northern Ireland. CiNI represents the interests of its 114 member organisations, providing policy, information, training and participation support services to members in their direct work with and for children and young people. CiNI has recently opened up its membership to colleagues in the children’s statutory sector recognising that the best outcomes for children are increasingly achieved working in partnership with all those who are committed to improving the lives of children and young people in Northern Ireland. CiNI is a member of the Child Poverty Coalition lead by Save the Children which has recently formed to campaign for an end to child poverty in NI.

2b. CiNI welcomes this opportunity to submit written evidence to the Committee on its Inquiry into Child Poverty. We would be happy to follow up with oral evidence to the Committee. We would also be keen to facilitate and support relevant members in delivering oral evidence to the Committee.

3. General Comments

Draft Programme for Government and Draft Budget 08-11

3a. CiNI welcomes the Executive’s commitment to take action to tackle child poverty. While we note the targets set - to work towards the elimination of severe child poverty by 2012 and to work towards the elimination of poverty in Northern Ireland by 2020, including lifting 67,000 children out of poverty by 2010 - it is extremely concerning that these challenging targets are not backed by a commitment of significant resources and indeed actions and activities which can begin the process of tackling child poverty.

3b. In fact recent research evidence demonstrates quite starkly the significant level of under investment in local children and young people when compared to children and young people in neighbouring jurisdictions. The NICCY Research on Public Expenditure on Children and Young People[2] (2007) highlighted significant disparity in spend on children’s personal social services. The expenditure per child in Northern Ireland on personal social services in Northern Ireland is £287. In Scotland it is £513; in Wales £429.10; and in England it is £402.

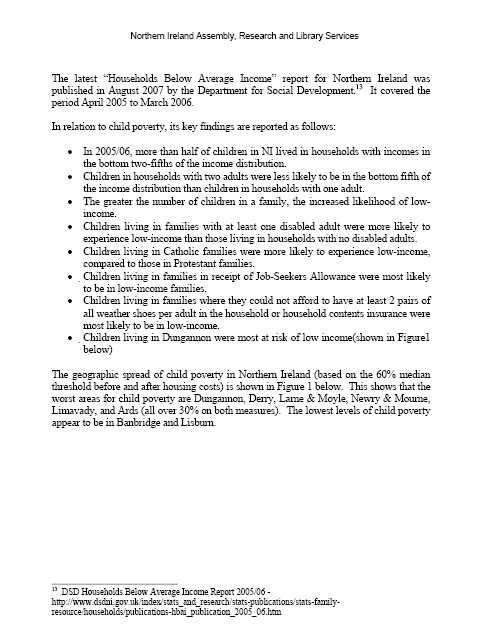

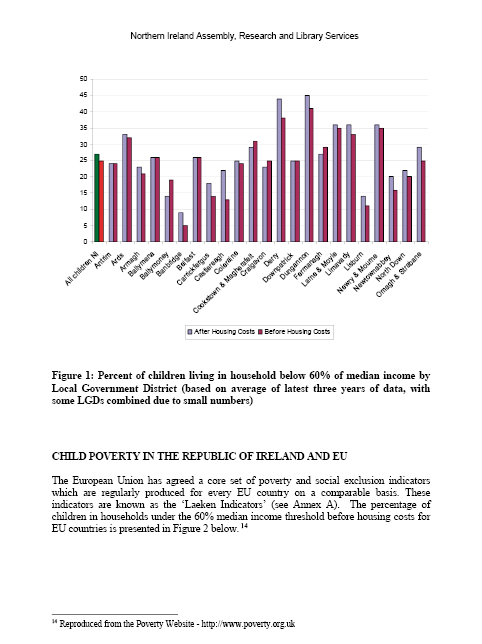

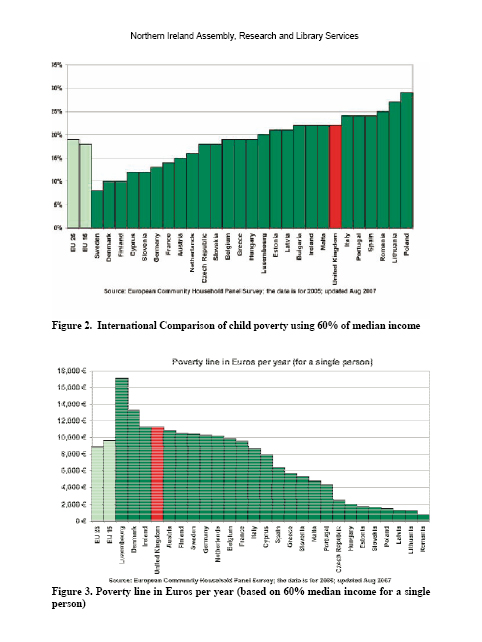

3c. CiNI would strongly advocate that the Executive give due regard to the findings of the NICCY research when making its final budget decisions. We would welcome a formal response from the Executive on the weighting it has attributed to the research findings when making its final budget decisions. Specifically we would urge the DHSSPS to explicitly demonstrate in its final budget outcome the steps which it is taking to address the level of underspend on children’s personal social services in NI.