Session 2007/2008

Third Report

COMMITTEE FOR THE OFFICE OF THE FIRST MINISTER AND DEPUTY FIRST MINISTER

Final Report on the Committee’s Inquiry into Child Poverty in Northern Ireland

VOLUME ONE

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE

RELATING TO THE REPORT AND THE MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

Ordered by The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and

Deputy First Minister to be printed 4 June 2008

Report: 08/07/08R (The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister is a Statutory Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 46. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental Budgets and Annual Plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of relevant primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the First Minister and deputy First Minister.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee is as follows:

- Mr Danny Kennedy (Chairperson)

- Mrs Naomi Long (Deputy Chairperson)

- Ms Martina Anderson

- Mr Tom Elliott

- Mrs Dolores Kelly

- Mr Barry McElduff

- Mr Francie Molloy

- Mr Stephen Moutray

- Mr Jim Shannon

- Mr Jimmy Spratt

- Mr Jim Wells

Table of Contents

Volume One

Section

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

1. Introduction

2. Approach of the Committee and focus of the report

3. Definition and measurement of child poverty

4. The evidence-base for the prevention of child poverty

5. Strategies to tackle child poverty in Northern Ireland

6. Policies to increase income

7. Tackling rising costs and financial exclusion

8. Promoting employment

9. Measures to tackle long-term disadvantage

10. Cross-cutting approaches

11. Conclusions

Appendices

1. Minute of Proceedings

2. Minutes of Evidence

Volume Two

Appendices

3. List of Written Submissions to the Committee

4. Written Submissions to the Committee

5. List of Witnesses Who Gave Evidence to the Committee

6. List of Research Papers

7. Research Papers

8. List of Other Evidence Considered by the Committee

9. Other Evidence Considered by the Committee

10. List of Abbreviations

Executive Summary

Purpose of the Report

Eliminating child poverty is one of the principal long-term objectives of the Executive and the Committee commends the Executive for adopting child poverty as a priority in the Programme for Government. In this report the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister has sought to develop a detailed understanding of child poverty in Northern Ireland and to use this understanding as the basis for the development of constructive suggestions to assist the Executive, and indeed future administrations, in developing a robust strategy to eliminate child poverty.

Child Poverty in Northern Ireland

A lack of money and low levels of income are at the core of child poverty. The most widely accepted measure of poverty is a measure of relative low income. Children are identified as being in relative income poverty if household income is less that 60% of the median household income in the UK. However, child poverty is about more than just a lack of money. Living in poverty has the potential to limit the aspirations and expectations of children and thereby contribute to a renewed cycle of poverty.

The Committee found that although levels of child poverty did fall in the late 1990s and in the early part of this decade, there has been no significant decrease in levels of child poverty during the past three years and there are still more than 100,000 children living in relative income poverty in Northern Ireland.

Tackling Rising Costs

The Committee is extremely concerned that, in the short-term, as a result of the rising cost of basic necessities such as food and fuel (the cost of a typical fill of home heating oil has risen to almost £600), there is the potential for levels of child poverty to rise over the next few years. The factors behind current economic challenges and such rising costs are in many ways outside the control of Government. Nevertheless, the Committee urges the Executive to apply pressure to the UK Government to provide further support to low income families to assist them in coping with the rising costs of basic necessities. The Committee welcomes the initiative to establish a taskforce to make recommendations on tackling fuel poverty and recommends that the Executive allocates specific resources to address the immediate crisis being faced by low income households.

Promoting Employment

The Committee was provided with evidence of the groups at most risk of child poverty and commissioned research into best practice in tackling child poverty. Not surprisingly, having a job is the factor that most protects families from poverty. A child in a workless household has a 58% chance of being in poverty compared with a risk of poverty of 14% for a child when one or both of their parents is working. However, the Committee was surprised to find that although employment significantly reduces the risk of poverty, almost half of children in poverty live in a household with at least one working parent. The significance of this finding is that it emphasises the importance of ensuring that economic development and employment strategies focus on increasing the quality of jobs that are created, as well as on the number of jobs.

The Committee identified that one of the most significant barriers to employment for low income families is the lack of availability of good quality, affordable childcare in Northern Ireland. This is particularly the case for lone parent families and families with a child who has a disability and is also a specific problem in rural areas. The Committee is of the view that childcare provision in Northern Ireland is woefully inadequate, recommends immediate action to resolve the dispute over responsibility for school aged childcare, and calls on the Executive to commit to the early development of a Childcare Strategy for Northern Ireland.

Policies to Increase Income

Evidence considered by the Committee highlighted the importance of policy in relation to taxation and benefits in tackling poverty. Countries with the lowest rates of children living in poverty (like those in the Nordic region) allocate the highest proportion of their gross national product to social expenditure, particularly family and other related social transfers. Some of these matters are outside the control of the Executive, but research considered by the Committee emphasised that the manner in which policies are implemented can have a significant impact on their effectiveness. For example, delivery systems for benefits can have a particularly significant impact on levels of severe poverty, as benefit levels are in fact set above the threshold for severe poverty. The Committee is therefore recommending that the Executive should develop a cross-departmental Benefit Uptake Strategy to assist low income families to obtain their full benefit entitlement.

Measures to Tackle Long-term Disadvantage

In the long-term, improving the health and well-being and educational outcomes of families in poverty has a critical role in helping to address the cycle of deprivation. The Committee recognises the successes that there have been over the past decade in improving overall educational outcomes and in increasing life expectancy and reducing levels of preventable illness. However, the gaps in educational and health outcomes between children living in poverty and children from more affluent backgrounds remain stubbornly unaffected. The Committee is convinced of the importance of early intervention and family based approaches in seeking to break the cycle of poverty and wishes to see the Executive establishing specific objectives to increase the level of investment across government in early years services and to increase the number of places provided within Sure Start. The Committee has also identified the need for legislation relating to the planning of children’s services to be reviewed to ensure that there is a truly joined-up approach to children’s services planning in Northern Ireland.

Overall Strategy to Tackle Child Poverty

The Committee has come to the conclusion that the development of a robust, properly resourced, implementation plan, supported by effective arrangements to ensure that all departments deliver on their child poverty commitments is critical if the Executive is to achieve its targets to reduce child poverty and eliminate severe child poverty. The Committee recommends the establishment of an independent expert panel that would examine and report to the First Minister and deputy First Minister on the contribution of the Programme for Government, Budget, Investment Strategy and associated delivery plans, to tackling child poverty. In addition, the Committee is proposing that the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) and the Department of Finance and Personnel should consult on the introduction of a system of financial incentives and penalties in relation to the delivery of cross-departmental priorities, such as child poverty.

Collective Commitment to Eliminating Child Poverty

Eliminating child poverty will require leadership and political will. The Committee believes that, in unanimously agreeing the recommendations in this report it has demonstrated that the political will exists to tackle child poverty in Northern Ireland. The Committee is of the view that a collective approach to the elimination of child poverty in Northern Ireland, which involves all political parties, and key public, private, voluntary and community partners, can be constructed. The starting point for a consensus on child poverty would be a comprehensive response to this report and its recommendations, in terms of a properly resourced, robust anti-poverty implementation plan.

Summary of Recommendations

Definition and Measurement of Child Poverty

1. We recommend that the Executive should, when defining, measuring and tackling child poverty, take account of the importance of ensuring that children and young people retain an expectation of achievement.

2. We support the decision by OFMDFM to adopt the 3-tiered approach to the measurement of child poverty used by the UK Government. In addition to measuring both absolute and relative low income, the Executive must ensure that material deprivation is also measured.

3. We recommend that OFMDFM and the Executive carefully consider the extent and distribution of poverty, including rural poverty, across Northern Ireland when developing their approach to tackling child poverty and when planning new investments and services. The Committee also recognises the importance of identifying and tackling smaller areas of deprivation, which are often masked by more affluent surrounding districts. It is vital that the Executive’s strategies and plans are based on a robust assessment of objective need.

4. We commend the Executive for adopting its target to work towards the elimination of severe child poverty. However, if this is to represent a meaningful commitment and not an aspiration, the Executive must establish, in advance of reviewing the Programme for Government, a baseline and system of measurement for the new severe poverty target.

Strategies to Tackle Child Poverty in Northern Ireland

5. We recommend that OFMDFM should move quickly to adopt the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy as the framework for its work to tackle poverty and social exclusion. Critically, this will allow OFMDFM to focus on remedying some of the deficiencies within the Strategy through the development of a properly resourced medium-term action plan, which includes SMART intermediate objectives and targets capable of delivering the Executive’s child poverty targets.

6. Following extensive deliberations, and taking particular account of the fact that the target to reduce child poverty by 50% by 2010 is a UK-wide target, the Committee has decided, on balance, to support the retention of the current target and to recommend that it be reviewed following publication of the 2006/2007 data later this year.

7. We accept that the Executive’s Anti-Poverty Strategy will have a critical role in filling many of the gaps in the current policy framework, but remain of the view that the Programme for Government and related PSAs need to be significantly strengthened if they are to ensure that resources and actions are effectively directed by departments towards the elimination of child poverty. As an immediate step, the Committee recommends that the First Minister and deputy First Minister:

- Establish target dates for the adoption of the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy and for the publication of a 3-5 year regional anti-poverty and social exclusion implementation plan, which should include the supporting objectives, targets and programmes for the delivery of the PSA targets to eliminate child poverty and severe child poverty.

- Re-establish the Ministerially led Poverty and Social Inclusion Stakeholder Forum.

- Establish a target date for the adoption of a regional Children and Young People’s Action Plan.

8. We recommend that that during the first review of the Programme for Government specific targets should be included in relation to:

- the level of additional investment across government in early years services over the Budget period;

- the number of additional places to be provided within Sure Start during the period covered by the Programme for Government;

- the number of high quality affordable childcare places to be created during this Programme for Government, including the % of such places that are to be created in areas of deprivation;

- a timeframe for implementation of recommendations arising from the taskforce established by the Minister for Social Development to reduce the impact of rising fuel costs on families on low income;

- the establishment of a pilot project in Northern Ireland which will reassure long term recipients of benefits that if they enter full-time work they will have an in work income better than they receive from their out of work benefits;

- the completion of a review, involving other relevant departments, to consider the issues addressed by the package for disabled children’s services in England, in relation to the provision of short breaks, accessible childcare, transition support and parents’ fora;

- the development of a cross-departmental Benefit Uptake Strategy.

9. We recommend that OFMDFM should insist on the inclusion within Programme for Government Delivery Agreements of a short-list of the changes to be introduced by each department to contribute to the objective of a shared and better future and that this should include measures which contribute to the reduction in levels of child poverty.

10. We wish to encourage the Committee for Social Development to carefully monitor the delivery of the commitment in the Investment Strategy to deliver 10,000 new social and affordable houses by 2013.

11. We consider the development of improved spatial information to be key to the Investment Strategy’s contribution to tackling weaknesses in infrastructure and to the Strategy’s capacity to take account of objective need. The Committee will therefore expect to receive an update on the progress made by the Strategic Investment Board, and departments, to develop such information within Investment Delivery Plans, during evidence sessions to follow-up the Committee’s report on the Programme for Government and Investment Strategy.

12. We recognise the particular role of the Committee for Finance and Personnel in monitoring compliance with the guidance on the role of procurement in contributing to the socio-economic and sustainability objectives of the Executive and recommend that all statutory committees examine their department’s compliance with the guidance when scrutinising Investment Delivery Plans.

13. The Executive must quickly distance itself from the approach of direct rule Ministers to the production of ambitious strategy documents which are then supported by unambitious action plans, which act more as a statement of existing departmental action than as a real plan for change. The Lifetime Opportunities implementation plan must focus on identifying the intermediate, 3-year outcomes that need to be achieved to deliver each of the long-term poverty reduction and social exclusion targets, detail the additional or changed outputs that are planned to achieve such outcomes, explain the timeframe for delivery and how the outputs are to be resourced.

14. We call on OFMDFM to ensure that the inclusion of narrative and descriptions of existing departmental activity is minimised within Implementation Plans supporting the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy.

15. We welcome the recognition of tackling poverty and disadvantage within the public expenditure planning process and ask OFMDFM and the Department of Finance and Personnel to ensure that this remains a feature in future Budget rounds.

16. We welcome the proposal to establish a sub-group of the Executive to identify the key actions that are required to deliver on the commitments in the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy. However, it is likely that this process will take some months and the Committee remains of the view that OFMDFM should have a role in challenging departmental Delivery Agreements to ensure the relevance and robustness of departmental targets and actions designed to contribute to the cross-cutting theme of a shared and better future.

17. We recommend that OFMDFM and the Department of Finance and Personnel should consider, following consultation with this Committee and the Committee for Finance and Personnel, the introduction of a system of financial incentives and penalties in relation to the delivery of cross-departmental priorities, such as child poverty.

18. We recommend that, in addition to the introduction of new performance management arrangements for the Programme for Government and the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy, OFMDFM should establish an independent panel of experts to report to the First Minister and deputy First Minister on the impact of the Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy and associated delivery plans, on families in poverty or at risk of poverty.

19. We wish to encourage other statutory committees, as part of their work to scrutinise the Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy, to challenge departments to identify the principal measures being introduced to reduce poverty and to set out how these measures are being resourced.

20. We wish to encourage leaders within local government, OFMDFM and the Department of the Environment to take account of the potential role of local government in tackling child poverty when developing new systems for community planning and during the development of agreements on funding and priorities between central and local government.

Policies to Increase Income

21. We recommend that, following a review of initial benefit uptake programmes, consideration should be given by the Department for Social Development to the establishment of longer-term benefit uptake contracts and the adoption of alternative methods to try to contact hard to reach families living in poverty.

22. We recommend that the Department for Social Development brings forward legislative proposals which would enable information to be shared with other government agencies to enable more effective approaches to be developed to encourage benefit uptake.

23. We recommend that, as a first major initiative in seeking to eliminate severe poverty, the Executive should commit to the development of a cross-departmental Benefit Uptake Strategy.

24. We consider that, given the similar challenges faced in seeking to reduce child poverty, the Executive should seek to ensure that policy on poverty reduction continues to be a matter for co-operation and information sharing on both a North/South and East/West basis.

25. The Committee calls on Ministers to lobby the UK Government for the reopening of an office dealing with tax credits in Northern Ireland and for improvements to verification procedures and the administration of the tax credit system.

Tackling Rising Costs and Financial Exclusion

26. The impact of fuel bills that are quite literally rising by the week is so significant that we believe OFMDFM, and indeed the wider Executive, must develop a specific plan of action to deal with the issue of rising costs for people on low income.

27. We urge the Minister for Social Development to ensure that the Fuel Poverty Taskforce considers all practical options, including options for additional payments or special tariffs for vulnerable groups. The Committee believes that in the current climate all options must be considered.

28. The Fuel Poverty Taskforce should consider how, in addition to potential investments by the public sector to increase levels of energy efficiency, the private sector, including the regulated utilities and major fuel companies, could more effectively contribute to minimising fuel costs for people on low income. The powers of the regulator to incentivise and enforce such an approach should also be considered. At a more local level, policies relating to the fuel choices of low income families may need to be reviewed and serious consideration should be given to how people on low income could be assisted to minimise costs though the creation of cooperatives, thereby enabling the bulk buying of fuel at a reduced price.

29. We recommend that the Executive prioritises the issue of high fuel costs during monitoring rounds and looks creatively at other options that could be used to finance the recommendations that emerge from the Fuel Poverty Taskforce.

30. The Committee asks the relevant departments and committees with responsibility for rates and water charges to ensure that, in developing measures to protect people on low income from further hardship, proper account is taken of the reduced incomes available to many vulnerable groups.

31. We recommend that within the Lifetime Opportunities Implementation Plan a new objective should be included to seek to minimise the impact of rising costs on low income households. As part of this objective, specific consideration should be given to the development of measures that minimise the cost to families on low income of government services. The principles of free education and free health care at the point of delivery must be at the heart of proposals to minimise the cost of services to families on low income.

32. We welcome the recognition by OFMDFM of the role of financial inclusion in tackling poverty and would wish to see this reflected in the Lifetime Opportunities Implementation Plan. We are aware that the Committee for Enterprise, Trade and Investment has launched an inquiry on credit unions and recommend that the Committee investigates whether the direct engagement of credit unions, in the manner employed by the Money Advice and Budgeting Service in the Republic of Ireland, would help to improve the impact of the debt advice service in Northern Ireland.

33. We recommend that the Consumer Council be asked to work with NIHE, the Department for Social Development and insurance companies to investigate low-cost house insurance options, which take account of the levels of home contents insurance required by families on low income.

Promoting Employment

34. We call on OFMDFM to initiate a review, involving other relevant departments, to consider the issues addressed by the package for disabled children’s services in England in relation to the provision of short breaks, accessible childcare, transition support and parents’ fora and, based on the outcome of the review, to make recommendations to the Executive on the development of a resourced programme of action to deliver equivalent improvements in Northern Ireland.

35. We call on OFMDFM, as a matter of priority, to resolve the dispute between the Department of Education and the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety over school aged childcare by assigning lead responsibility for childcare policy to the most appropriate department.

36. We call on Executive Ministers to ensure that before introducing welfare reform programmes which have been developed in other parts of the UK, careful consideration is given to their implementation in Northern Ireland, and, in particular, we recommend that an evaluation is carried out of whether necessary support services, such as childcare, are in place prior to their implementation.

37. We recommend that the Executive should set a date for the development of a long-term, properly resourced Childcare Strategy and take immediate action to resolve the funding crisis for school aged childcare. The Committee recommends that the Strategy should include specific targets to:

- increase the level of good quality, affordable childcare in areas of disadvantage;

- improve the level of appropriate, affordable childcare provision for children with a disability;

- improve access to affordable childcare in rural areas;

- reduce the length of time that it takes to become registered as a childminder;

- reverse the decline in registered childminders that is being experienced in some parts of Northern Ireland;

- enhance the training and development of staff working in early years settings.

38. We recommend that consideration be given to introducing a statutory duty to require sufficient childcare provision to meet the needs of the community in general and in particular those families on lower incomes and those with disabled children.

39. We recommend that specific targets for improving childcare provision in rural areas be included in the Childcare Strategy.

40. We recommend that making work pay should be a specific objective within the Lifetime Opportunities Implementation Plan and that the Department for Social Development, with the support of OFMDFM, should work with departments in the UK on the development of a pilot “Better off in Work” initiative in Northern Ireland.

Measures to Tackle Long-term Disadvantage

41. The Committee considers that more attention needs to be paid to identifying and targeting the population groups at most risk of poor educational or health outcomes with specific, evidence-based strategies that will deliver real improvements for such groups.

42. It is crucial that the Early Years Strategy being led by the Department for Education is properly resourced and is quickly followed by an implementation plan containing SMART targets. We recommend that the Early Years Strategy should include specific targets on:

- the level of additional investment across government in early years services over the Budget period;

- the number of additional places to be provided within Sure Start during the period covered by the Programme for Government;

- the additional support to be made available to help identify the additional educational and support needs of young children.

43. We recommend that OFMDFM and relevant departments and agencies, including, in particular, the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety and the Department of Education, review and update legislation underpinning children’s services planning with a view to:

- extending the duty to develop children and young people’s plans to at least include the Regional Health and Education Authorities;

- linking children’s services plans more directly with the outcomes of the Children’s Strategy, whilst retaining specific recognition in the legislation for children in need;

- strengthen the legislation, or statutory guidance, so that relevant organisations are required to co-operate, rather than participate, in children’s service planning and delivery.

Cross-Cutting Approaches

44. The Committee is of the view that:

(a) Further consideration should be given to how the process of Equality Impact Assessment could better inform policies in relation to their impact on groups at high risk of poverty; and

(b) The Anti-Poverty Unit in OFMDFM, with the support of the Department of Finance and Personnel, should have a role in challenging and reporting on whether key policies have taken adequate account of their impact on groups in poverty or at risk of poverty.

45. We recommend that OFMDFM should consider how to use the outcome of its work on Promoting Social Inclusion to improve understanding among policy makers and service providers of the groups which are most at risk of poverty and social exclusion and the steps that will have most impact in removing such groups from poverty and exclusion.

46. We recommend that the key recommendations from the Promoting Social Inclusion reports are integrated into the planning and implementation processes for the Programme for Government and Lifetime Opportunities Strategy.

47. We wish to encourage the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, in consultation with the Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development, to consider carefully how to utilise the funding package on rural poverty and social exclusion to maximise its impact on rural child poverty over the long-term.

Introduction

Inquiry Terms of Reference

1. At its meeting of 4 July 2007, the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister agreed to conduct its first inquiry into child poverty. The terms of reference for the inquiry were agreed at the Committee meeting on 3 October 2007.

Terms of Reference for the Child Poverty Inquiry

The Committee will examine the current strategic approach to tackling child poverty in Northern Ireland.

Specifically the Committee will:

- Examine the extent, intensity and impact of child poverty in Northern Ireland

- Consider the approach taken when formulating the current strategy including the extent of the engagement with key stakeholders

- Assess whether the existing strategy is capable of delivering the key targets for 2010 and 2020

- Examine whether the implementation mechanisms, resources and monitoring arrangements currently in place are adequate to ensure delivery of the key actions/targets

- Identify and analyse relevant experience elsewhere in terms of policy interventions and programmes

- Consider what further actions could be taken to tackle child poverty with particular focus on those that would be deliverable by the devolved administration

- Report to the Assembly by March 2008

The Inquiry Process

2. The inquiry into child poverty was formally launched on 17 October 2007. Advertisements requesting submissions by 16 November 2007 were placed in the local newspapers on 22 October 2007. In addition, the Committee agreed to write directly to Assembly Ministers and a number of interest groups, to request submissions on each of the matters included within the terms of reference of the inquiry. A list of those organisations and groups that submitted written evidence is attached at Appendix 3.

3. On 17 October 2007, the Committee decided to produce an interim report on its inquiry for the purpose of influencing the draft Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland. The interim report reflected the Committee’s initial consideration of the research and evidence presented to Members and sought to highlight to the Assembly and the Executive some of the key issues that needed to be taken into account before finalising the Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy. The report was published on 09 January 2008. The Committee did not seek a specific response to the report, rather it was anticipated that the final Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy and related plans would represent the Executive’s response to the interim report. The Committee’s views on the extent to which the final Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy adequately address the challenge of seeking to eradicate child poverty are set out in section 5 of the report.

4. The complexity and cross-departmental nature of seeking to develop robust recommendations on child poverty is reflected by the fact that the Committee received 48 written submissions and considered oral evidence from 28 key stakeholders and 7 government departments. A list of the witnesses who provided oral evidence to the Committee is attached at Appendix 5. Transcripts of the oral evidence sessions are attached at Appendix 2.

5. In addition, following a number of oral evidence sessions, the Committee sought and received additional information, to further inform the Child Poverty Inquiry. Copies of these additional papers are included at Appendix 9.

6. The Committee also commissioned detailed research papers on both the definition and measurement of child poverty, and on potential solutions to child poverty and severe child poverty, from the Assembly’s Research and Library Service. Copies of these papers are included at Appendix 7.

7. On 30 April 2008, the Committee held an informal meeting to review the evidence to the inquiry and received presentations from representatives of Combat Poverty Agency and the New Policy Institute on priorities for tackling child poverty and good practice in the UK and the Republic of Ireland in addressing such priorities. Copies of the presentations received are included at Appendix 9.

8. The Committee was also eager to receive more direct evidence about the experiences of children and young people living in poverty. Save the Children and the University of Ulster therefore provided the Committee with a briefing on 30 April 2008 on a number of research projects, including some as yet unpublished research, which involved children and young people offering their views on the impact of poverty and on potential solutions. A copy of the briefing paper from Save the Children and the University of Ulster is included in the report at Appendix 9.

9. The Committee considered a draft report on child poverty in Northern Ireland at its meetings on 21 May 2008 and 28 May 2008 and on 4 June 2008 the Committee agreed its final report and ordered that the report be printed.

Acknowledgements

10. The Committee for the Office of the First Minster and Deputy First Minster would like to express and record its appreciation and thanks to all the organisations who contributed to the inquiry.

Approach of the

Committee and Focus of the Report

11. Members of the Committee are committed to improving the lives of our most disadvantaged children and young people. This is the reason that the Committee selected the issue of child poverty as the subject for its first inquiry. The Committee considers that it can best deliver on this commitment by paying careful attention to the evidence presented to it and only making recommendations that are clearly evidence-based. The report includes a detailed assessment of levels of child poverty in Northern Ireland, including the identification of groups at most risk of experiencing child poverty. It also seeks to identify the factors that protect against child poverty and draws on research in relation to international best practice in tackling child poverty.

12. The Committee recognises that eliminating child poverty is an extremely challenging target. If we are to have any hope of achieving this target there must be a collective commitment to action across government and indeed throughout society. This commitment will also need to be sustained by successive administrations. The Committee has therefore sought to adopt a constructive approach to the development of the report and in its consideration of evidence has endeavoured to recognise good practice where it exists. The Committee is also realistic about the economic and social challenges facing Northern Ireland over the next few years and has sought to make recommendations which take account of the reality of rapidly rising fuel costs and difficult economic conditions. There can be little doubt that major reforms will be required if we are to be successful in tackling child poverty. Delivering such reforms in current circumstances will require leadership, focus, determination and creativity.

13. All government departments have a contribution to make to tackling child poverty. During the course of this inquiry the Committee has engaged to some extent with all eleven departments and took oral evidence from seven departments. However, it would not have been practicable for this Committee to seek to scrutinise all the policies and programmes in each of these departments which are, or should be, contributing to reducing child poverty. In its report the Committee has therefore sought to focus on the overall strategy to tackle poverty as set out in the Programme for Government, Budget and Investment Strategy and the Lifetime Opportunities Strategy and on the resourcing and delivery of these strategies. In addition, the Committee has identified a number of gaps in the current policies and strategies and has made specific recommendations on how these should be filled.

14. Eliminating child poverty will require a long-term strategy. However, very challenging medium-term targets have been established to reduce child poverty by 50% by 2010 and to eliminate severe child poverty by 2012. The Committee has therefore sought to contribute to short/medium-term solutions as well as offering recommendations on longer term strategies.

15. In commencing this inquiry, the Committee was mindful of the fact that many of the potential solutions to child poverty are not under the control of the Executive. In particular, taxation and tax credits are not devolved and are the responsibility of the UK Government. In addition, whilst benefits are devolved, the provisions of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and the practical implications of operating different benefit systems in Northern Ireland from elsewhere in the UK, limit the Executive’s capacity to introduce changes to the benefit system in the short-term.

16. The terms of reference for the inquiry recognise this difficulty and it was agreed that the inquiry would focus on those [actions] that would be deliverable by the devolved administration and organisations providing evidence to the Committee were encouraged to focus on matters under the control of the Executive. Within this report the majority of the Committee’s recommendations relate to issues for which the Executive has direct control, though, in a small number of instances, the Committee has sought to encourage the Executive to use its influence with the UK government to seek changes to policy on matters, which either are not devolved or are governed by parity provisions.

Definition and Measurement of

Child Poverty

17. The Committee quickly discovered that defining what we mean by child poverty and seeking to establish systems to measure child poverty are very complex. Such is the complexity of this issue that the Committee commissioned three separate research papers on the subject.

Definition of Child Poverty

18. There would seem to be widespread agreement that lack of money and low levels of income are at the core of child poverty. However, the Committee was encouraged to recognise that child poverty is about more than just a lack of money.

19. The Committee research paper on the measurement of severe and persistant poverty[1] advises that there is no straightforward and generally agreed definition of poverty. Poverty is seen today as a multi-dimensional issue and understood by many as the inability to participate in society - economically, socially and culturally.

20. Children’s organisations such as Barnardo’s and Playboard highlighted the impact that poverty can have on limiting the aspirations and expectations of children and young people and expressed the view that these dimensions of poverty should be taken into account when defining and measuring child poverty, but more particularly when seeking to tackle child poverty.

21. The relationship between poverty and exclusion is highlighted in the Irish Government’s definition of poverty[2].

People are living in poverty if their income and resources (material, cultural and social) are so inadequate as to preclude them from having a standard of living which is regarded as acceptable by Irish society generally As a result of inadequate income and other resources people may be excluded and marginalised from participating in activities, which are considered the norm for other people in society.

22. In its written submission to the Committee[3], the Department for Social Development characterises the UK Government’s definition of poverty as being technical, but one that attracts broad agreement at home and internationally.

23. Under this definition, poverty is defined as a household with an equivalised income less than 60% of the UK median equivalised household income. “Equivalised” means that the actual income has been adjusted to take account of the household size and age structure and 60% is a conventional internationally accepted fraction of the median.

24. In 2003[4], in addition to the above measure of relative low income, which seeks to assess whether the poorest families are keeping pace with the growth of incomes in the economy as a whole, the UK government decided that its assessment of child poverty would also seek to measure absolute low income and material deprivation.

Measurement of Child Poverty

25. The research paper[5] considered by the Committee on the measurement of child poverty advised that measurement of poverty is as complex as its definition. This is undoubtedly the case and at times it seemed that the measurement of child poverty required an inquiry in its own right. As well as considering two further research papers which dealt with the measurement of child poverty and severe child poverty, the Committee received a considerable volume of written and oral evidence on the subject.

26. The research paper[6] on the measurement of severe and persistent poverty described in detail the approach of the UK Government to the measurement of child poverty. It contains three elements:

Absolute low income: This measure seeks to evaluate whether the poorest families are seeing their incomes rise in real terms. It determines the number of children in families with incomes below a defined ‘fixed’ monetary value or ‘threshold’. Government maintain that this measure will help to ascertain whether the poorest families are experiencing a rise in income in real terms.

Absolute low income is measured using a fixed or set poverty line. For example, the fixed poverty line for a couple with two children was set at £210 per week which was 60% of the ‘average’ (or median) weekly income in 1998/99. The fixed poverty line does not move from year to year - it is held constant in real terms.

Relative low income: This measure seeks to determine whether the poorest families are keeping pace with the growth of incomes in the economy as a whole. As outlined above, this measure assigns a monetary value or ‘threshold’ as a cut off point below which people or families are deemed to be living in poverty. The difference between this measure and the last is that the threshold can change from year to year - as the population becomes better (or worse) off. The official UK ‘relative threshold’ for child poverty is 60 per cent of the ‘average’ or ‘typical’ household income for that year (before housing costs).

In real terms this means that in 2005/06 people are considered to be in poverty if they have an income (before housing costs) of:

- £108 per week for a single adult

- £186 per week for a couple with no dependent children

- £223 per week for a single adult with two dependent children

- £300 per week for a couple with two dependent children

Material deprivation and low income combined: This new measures seeks to provide a wider measure of people’s living standards. It examines the circumstances of children living in low income households (below 70 percent of contemporary median equivalised income) - which are also materially deprived. The material deprivation information is collected through the Family Resources Survey which asks parents a series of questions about the goods, services and household items available to the children and themselves. If they do not have these items, they are asked whether this is because they do not want them or because they cannot afford them.

27. In its written submission to the inquiry, the Committee for Social Development[7] advocated the importance of measuring deprivation as well as income.

The Committee does not believe that an income only measure gives an accurate account of the levels of child poverty or severe child poverty and would wish to see a mixed measure employed to include relevant deprivation measures.

28. During the inquiry the Committee’s attention was drawn to a number of alternatives to the UK model for the measurement of child poverty. For example, in the Republic of Ireland, child poverty is measured using a mixed measure based on less than 60 per cent mean household income plus enforced lack of at least one of eight indicators of ‘basic’ deprivation. The Bare Necessities report[8] which specifically examined poverty and social exclusion in Northern Ireland, also looked at a combination of income and deprivation, but in this case, a survey was carried out to ascertain the items and activities felt to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living, as the basis for devising a consensual mixed poverty measure.

29. In Europe, the Laeken indicators[9] are a set of relative poverty indicators commonly agreed and used within the European Union to monitor progress in this area. The relative threshold is set at 60 per cent of median income. This allows comparable statistics on poverty and social exclusion to be published for every EU country. Eurostat, however, goes beyond the 60 per cent threshold and publishes a range of poverty thresholds – for example at 40, 50, 60 and 70 per cent - of both median and mean income.

30. In 2006 a study by two Northern Ireland academics[10] evaluated a number of national and international measures of child poverty. The study considered the importance of choice of measure and made some recommendations about how poverty rates in Northern Ireland should be measured and reported in the future. The study advised that:

- It is better to report and utilise a number of measures of poverty

- Longitudinal data is better than cross sectional data for the measurement of persistent poverty

- Where the government’s new ‘tiered’ measure is concerned – this will produce poverty rates ranging from 14 to 40 per cent depending on the tier being used – however what is important is not so much the measure used but that it is applied consistently over time points.

31. In a written submission[11] to the Committee, OFMDFM advised that it proposes to use the UK Government’s 3-tiered approach to the measurement of child poverty, though it was noted that information is not yet available in Northern Ireland on the mixed measure of income and deprivation. There was also significant support among organisations that gave evidence to the Committee for adoption by the Northern Ireland Executive of the approach used by the UK government, on the basis that it allows direct comparison with other European countries and takes account of absolute poverty and material deprivation, as well as relative poverty.

32. The Committee is of the view that lack of money and low incomes are key components of poverty. However, poverty also has the potential to have life-long and indeed generational impacts. The Committee therefore recommends that the Executive should, when defining, measuring and tackling child poverty, take account of the importance of ensuring that children and young people retain an expectation of achievement.

33. The Committee supports the decision by OFMDFM to adopt the 3-tiered approach to the measurement of child poverty used by the UK Government. The Committee is of the view that in addition to both absolute and relative low income the Executive must ensure that material deprivation is also measured. This is likely to be particularly important in the next few years, as it is the combined measure of low income and deprivation which is most likely to reflect the impact of rising costs on families in poverty.

34. In the Committee’s interim report[12] it was noted that there are two different approaches to measuring relative income poverty; before housing costs or after housing costs are taken into account12. Where possible in this report the Committee has utilised child poverty figures calculated before housing costs are taken into account. The Committee adopted this approach as it is the standard methodology for comparing poverty levels across Europe. In addition, in its submission to the Committee, Save the Children[13] argued that the After Housing Costs Measure does not provide an appropriate comparison with GB, as the housing costs in NI have (in the past) tended to be lower than GB, while most other costs have been higher, including food, fuel, childcare and clothing.

Child Poverty in Northern Ireland

35. OFMDFM, in its evidence to the Committee[14], advised that the main vehicle for measuring child poverty in Northern Ireland is the Family Resource Survey (FRS) and the related publication, Households Below Average Income Series (HBAI) Northern Ireland.

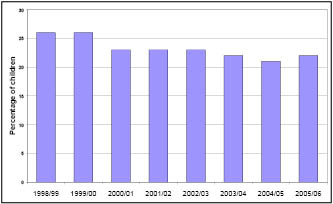

36. In the rest of the UK the FRS has been in place since the mid 1990s. The UK Government has determined that poverty levels in 1998/1999 provide the baseline for its target to half child poverty by 2010 and levels of relative income have been published for every year since 1998/1999. Figure 1 outlines the trend in child poverty levels in the UK as measured by relative income.

Figure 1 ‘Relative’ poverty line measure - UK

Source: Households Below Average Income 2005/06

37. The FRS only commenced in Northern Ireland in 2002. As a result, in order to determine progress in Northern Ireland against the target to reduce child poverty by 50% by 2010, it has been necessary to estimate child poverty levels for the years 1998/1999 to 2001/2002. OFMDFM presented a detailed paper[15] to the Committee at the end of January 2008 describing how it has calculated child poverty levels in Northern Ireland. The table below sets out the results of these calculations.

Table 1 Relative income child poverty in N. Ireland

|

Year |

Number of children in poverty |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

1998/1999 |

135,000 |

29 |

|

1999/2000 |

134,000 |

29 |

|

2000/2001 |

121,000 |

26 |

|

2001/2002 |

118,000 |

26 |

|

2002/2003 |

116,000 |

26 |

|

2003/2004 |

113,000 |

26 |

|

2004/2005 |

106,000 |

24 |

|

2005/2006 |

110,000 |

25 |

38. The results in both the UK and Northern Ireland indicate that the proportion of children living in households below the relative poverty threshold declined gradually between 1998/1999 and 2004/05 – an overall reduction of five percentage points- and then increased slightly in 2005/2006 by 1% point.

39. Research[16] considered by the Committee reported that the proportion of children below the absolute low income threshold also moved downward over time - from 26% in 1998/1999 to 13% in 2005/2006. The rate of change was greatest between 1998/99 and 2001/02, and slowed thereafter.

40. Dr Stephen Donnelly, Head of Research in OFMDFM, summarised recent trends in relation to child poverty in Northern Ireland[17].

Absolute low income is defined as the income of people on low wages, and whether their real incomes increase faster than the rate of inflation. OFMDFM has measured that, and results indicate a very positive trend — people who are on absolute low incomes are better off today, in real terms, than they were three or four years ago. Since 2003, the levels of relative income poverty have levelled off for working households and those with children, and they have increased to a certain extent for pensioner households. As a whole, poverty levels in Northern Ireland seem to have plateaued, but the absolute poverty levels are increasing over time.

41. Save the Children[18], in their evidence to the Committee emphasised the relative lack of progress that there has been in recent years.

What is clear from the figures is that the child poverty rate has not decreased over the past four years in which it has been measured in Northern Ireland. That is, obviously, an issue of real concern.

42. During the evidence session with OFMDFM, Members expressed real concerns that the current levels of child poverty may indeed be considerably worse than in the reports before the Committee. This was accepted by Dr Donnelly, who offered the following response[19] to Members’ concerns that the recent doubling in the cost of home heating oil would not have been not reflected in the poverty levels being reported to the Committee.

The problem is that our figures are about a year out of date and much of the upward pressure that will undoubtedly push up poverty levels has not been reflected in the statistics yet.

43. On the basis of the Committee’s concerns, Dr Gerry Mulligan, Head of the Equality/Rights and Social Need Division in OFMDFM, agreed to undertake modelling work to assess the potential impact on poverty levels of various assumptions about the rising costs of essential items such as fuel and food. The results of this work were provided to the Committee on 12 May 2008[20] and are reported in the section of the report dealing with the achievement of child poverty targets.

44. Whilst welcoming the reduction in child poverty levels between 1998/99 and 2004/05, there can be no doubt that poverty levels are still far too high in Northern Ireland. Having more than 100 000 children living in poverty in the 21st century is totally unacceptable.

45. The Committee is very concerned that there has, at best, been a levelling off in child poverty levels in recent years and is very apprehensive about the impact of the current economic climate and rising costs on poverty levels in Northern Ireland.

Comparison of child poverty levels in Northern Ireland with UK regions, the Republic of Ireland and Europe

46. A 2006 report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation[21], ‘Monitoring poverty and social exclusion in Northern Ireland’, concluded that Northern Ireland stands out from Great Britain in the following ways:

- The high number of people receiving out-of-work benefits, in particular: the 19% of working-age people receiving one of the key out-of-work benefits, the 13% of working-age people receiving one of the key out-of-work sickness and disability benefits.

- The high number of disabled people, especially related to mental health, reflected in the 9% of working-age people receiving Disability Living Allowance and the 3% of the whole adult population receiving that benefit for mental health reasons.

- The extent of low pay among full-time employees, reflected in the 22% paid less than £6.50 an hour and the high numbers receiving in-work benefits (19% of working-age households receive working and/or child tax credits). By contrast, the 43% of part-timers who are paid less than £6.50 an hour is below the Great Britain average.

- The high numbers without paid work, specifically the 31% of people aged 16 to retirement lacking paid work, alongside the very low proportion (7%) of people in that age group wanting paid work.

- The very high fuel poverty rate, with 24% of households unable to afford to heat their home to an adequate standard – although the proportion of homes lacking central heating is actually much lower than in Great Britain.

47. It is not therefore surprising that relative income poverty in Northern Ireland is higher than in other parts of the UK, with 25% of people in Northern Ireland considered to be in relative income poverty compared with 22% in the UK. Table 2[22] indicates that when calculated before housing costs are taken into account, the levels of child poverty in Northern Ireland are higher than in England, Scotland and Wales.

Table 2: Number and % of children in poverty by UK nation and English regions,

presented as 3 year running average (2003/04-2005/06), before housing costs.

|

Nation/Region |

Risk of poverty (%) |

Numbers |

|---|---|---|

|

England |

22 |

2,376,000 |

|

North East |

28 |

140,000 |

|

North West |

24 |

360,000 |

|

Yorkshire and the Humber |

25 |

275,000 |

|

East Midlands |

23 |

207,000 |

|

West Midlands |

26 |

312,000 |

|

Eastern |

16 |

192,000 |

|

London |

26 |

416,000 |

|

Inner London |

35 |

175,000 |

|

Outer London |

21 |

210,000 |

|

South East |

13 |

221,000 |

|

South West |

17 |

170,000 |

|

Scotland |

22 |

220,000 |

|

Wales |

24 |

144,000 |

|

Northern Ireland |

25 |

100,000 |

Source: HBAI 1994/95-2005/06

48. The levels of relative income child poverty in Northern Ireland for 2003/04- 2005/06, if calculated after housing costs are taken into account, are lower than in England, but higher than in Scotland and Wales, though these figures were produced in advance of the steep rise in housing costs that has been experienced in Northern Ireland over the past few years[23].

49. The research considered by the Committee demonstrates the complexity of comparing child poverty. However, its conclusion is that the level of child poverty in Northern Ireland would appear to be above that in Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland and well above the EU average.

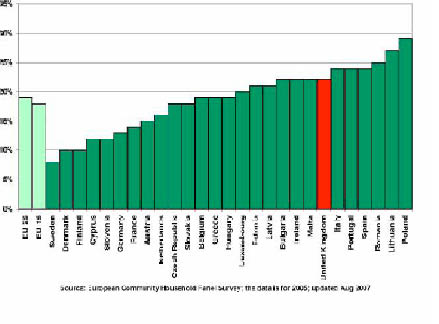

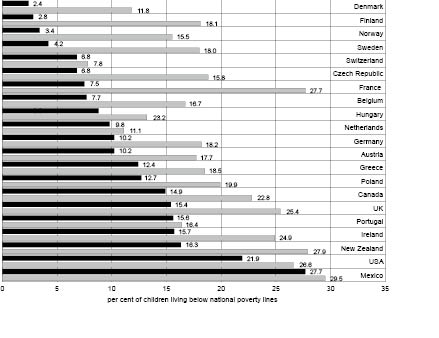

50. The percentage of children in households under the 60% median income threshold before housing costs for EU countries is presented in Figure 2 below[24].

Figure 2 International Comparison of child poverty using 60% of median income

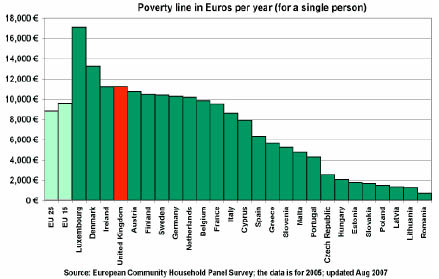

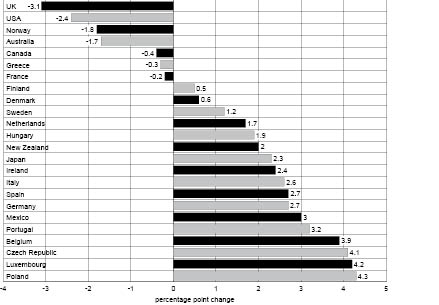

51. Figure 2 demonstrates that child poverty levels in both the UK and Ireland are well above the European average. It is however, worth noting that, as demonstrated by Figure 3[25], the poverty line is drawn at a much higher level in richer countries such as the UK and Ireland.

Figure 3. Poverty line in Euros per year (based on 60% median income for a single person)

52. Also, whilst child poverty levels in the UK are well above the EU average, it is important to recognise that international research of poverty in rich countries found that the UK leads the rest of the countries in its overall reduction in the level of child poverty[26]. Using the measure of relative income poverty it has been estimated that in the UK approximately 600,000 children have been lifted out of relative poverty between 1998/99 and 2005/06. In Northern Ireland, OFMDFM has estimated that approximately 25,000 children have been lifted out of poverty since 1998/99[27].

Variation in Levels of Child Poverty

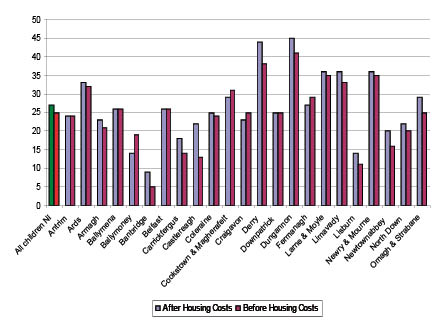

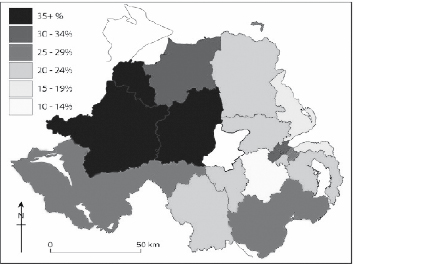

53. Child poverty is a reality in all parts of Northern Ireland, but poverty levels in Northern Ireland vary significantly. The geographic spread of child poverty in Northern Ireland (based on the 60% median threshold before and after housing costs) is shown in Figure 4[28].

Figure 4: Percent of children living in household below 60% of median income by Local Government District (based on average of latest three years of data, with some LGDs combined due to small numbers)

54. Research indicates that poverty levels are higher in Western areas of Northern Ireland, as well as in parts of Belfast.

Figure 5 Child Poverty by Parliamentary Constituency

Source HBAI 2004/2005

55. In its submission to the Committee, the Children’s Law Centre[29] emphasised the intensity of poverty in some areas of Northern Ireland.

Poverty in Northern Ireland is considerably more concentrated than in Britain. 25 out of 566 wards (4.4%) have concentrations of child poverty in excess of 75% compared to 180 out of 10,000 wards in Britain (1.8%) with child poverty rates of 50% to 70%.

56. The Committee was surprised to hear from the Rural Community Network (RCN) of the extent of poverty that exists in rural areas. In correspondence with the Committee, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development provided the following table comparing child poverty levels in rural and urban areas within Northern Ireland.

Table 3: Children in Poverty by Urban Rural Group, 2005/06

|

|

Before Housing Costs |

After Housing Costs |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of Children in Poverty |

% of Children in Poverty |

No. of Children in Poverty |

% of Children in Poverty |

|

|

BMUA |

26,400 |

20% |

31,200 |

23% |

|

Urban East |

11,600 |

21% |

13,700 |

25% |

|

Urban West |

28,700 |

33% |

31,500 |

36% |

|

Rural East |

16,300 |

27% |

17,100 |

28% |

|

Rural West |

25,400 |

28% |

28,600 |

31% |

|

NI |

108,400 |

25% |

122,100 |

29% |

Source: Family Resources Survey NI, 2005/06, DSD

57. Perhaps less surprising was the evidence[30] presented to the Committee by the Western Investing for Health Partnership that rural communities suffer particularly in relation to access to services.

Rurality has a huge impact on poverty and Belleek and Boa ward in Fermanagh ranks as the most deprived ward in N.I in terms of the proximity to Services Domain.

58. The Committee recommends that OFMDFM and the Executive carefully consider the extent and distribution of poverty, including rural poverty, across Northern Ireland when developing their approach to tackling child poverty and when planning new investments and services. The Committee also recognises the importance of identifying and tackling smaller areas of deprivation, which are often masked by more affluent surrounding districts. It is vital that the Executive’s strategies and plans are based on a robust assessment of objective need.

Measurement of Severe Poverty

59. In its interim report the Committee welcomed the Executive’s commitment in the Programme for Government to work towards the elimination of severe child poverty by 2012 and called on OFMDFM to ensure that adequate resources are available to properly measure and assess progress towards this target.

60. It would seem that whilst the target to work towards the elimination of severe child poverty has been retained, OFMDFM is not yet in a position to advise how it proposes to measure progress towards this target. In correspondence to the Committee[31], OFMDFM advised that Junior Ministers have sought advice on indicators and measures in relation to severe child poverty and work is continuing on this.

61. In recognition of the absence of an agreed definition of severe child poverty, the Committee commissioned specific research on options for the measurement of severe child poverty. This research[32] identified that whilst the Measuring Child Poverty paper of 2003 refers to the use of low income thresholds for measuring depth of poverty, the UK Government does not specifically define severe child poverty in this paper or elsewhere. The research therefore considered a number of independent studies of severe child poverty.

62. In 2007, Save the Children published a study which aimed to identify its own measure of severe child poverty using a combination of existing UK government indicators. Children are classified as being in “severe” poverty if they are in households with very low income (i.e. below 50 per cent threshold), in combination with material deprivation (deprived of both adult and child necessities, at least one of which shows some degree of severity, i.e. two or more items). Those in households below 70 per cent of median income, in combination with some form of adult or child deprivation are classified as being in non-severe poverty. The remainder are classified as not being in poverty.

63. The study found that 10.2% (1.3 million) of children in the UK are classified as being in severe poverty. The study revealed very high levels of severe poverty in London and Wales, and a relatively high rate of 9.7% in Northern Ireland. This research estimated that 44,000 children under 18 were living in severe poverrty in Northern Ireland while an earlier study in 2004 put the figure at 8% or 32,000 children under the age of 16. The Northern Ireland Anti-Poverty Network[33] reported to the Committee that in Northern Ireland 2% of people are living on less than £100/week before housing costs and 5% after housing costs.

64. In considering the severity of poverty, consideration may need to be given to not only the depth of poverty but also its duration.

65. The UK government publishes figures on persistent low income[34], with low income being defined as below 60 per cent of median income. Persistent low income is defined as being in a low income household in at least three of the last four years. The table below shows that small reductions in persistent low income have occurred over the period 1991 to 2004, although the extent of persistent low income amongst children in GB remains relatively high at 13% before housing costs and 17% after housing costs.

Table 4 Percentage of children living below 60% of median income in at least 3 out of 4 years, GB

|

Year |

Before Housing Costs |

After Housing Costs |

|---|---|---|

|

1991 to 1994 |

20 |

25 |

|

1994 to 1997 |

17 |

24 |

|

1997 to 2000 |

17 |

22 |

|

2000 to 2003 |

15 |

19 |

|

2001 to 2004 |

13 |

17 |

Source: HBAI 1994/95-2005/06

66. A recent study in Northern Ireland[35] sought to track a fixed group of individuals or households over time and thereby help to explain movements in and out of poverty. The survey tracked the same respondents over a four year period and, in the analysis, children were defined as belonging to one of the following five groups:

- No poverty – not in poverty in any of the four years

- Short-term no severe poverty – in poverty in either one or two of the four years but no severe poverty

- Short-term and severe poverty – in poverty in at least one or two of the four years and at least one year in severe poverty

- Persistent no severe poverty – in poverty in at least three of the four years but no years in severe poverty

- Persistent and severe poverty – in poverty for at least three years and at least one year in severe poverty

67. Early results from this research provide new evidence of the prevalence of persistent and severe poverty in Northern Ireland. Table 5 below reveals that relatively large proportions of children in Northern Ireland have experienced severe and persistent poverty.

Table 5 Poverty type over four years, Northern Ireland

|

Poverty type |

% |

|---|---|

|

No poverty |

52 |

|

Short-term no severe |

15 |

|

Short term and 1+ severe |

12 |

|

Persistent no severe |

9 |

|

Persistent and 1+ severe |

13 |

|

Base = 550 |

100 |

Source: NIHPS 2001-2004

68. During the inquiry, the Committee has received convincing evidence of the importance of measuring severe poverty. The Committee was advised that despite the decline in levels of child poverty there is little evidence of a decline in severe poverty. In its written submission to the inquiry, Save the Children[36] highlighted its concerns that the reductions in child poverty in recent years may have been as a result of lifting those closest to the poverty line and therefore the “easiest to reach”, above the poverty threshold.

The intensity of poverty must also be considered. Our report, ‘Britain’s Poorest Children’, found that despite hundreds of thousands of children being lifted out of poverty in Great Britain over recent years, there was little change in the number of children experiencing severe child poverty.

69. The Committee fervently believes that, in taking forward its strategy to tackle poverty in Northern Ireland, the Executive must ensure that the poorest families benefit from the new policies and approaches that are being developed. We therefore commend the Executive for adopting its target to work towards the elimination of severe child poverty. However, if this is to represent a meaningful commitment and not an aspiration, the Executive must establish, in advance of reviewing the Programme for Government, a baseline and system of measurement for the new severe poverty target. The Committee hopes that the research which it has commissioned into the measurement and tackling of severe poverty will be of assistance in this regard.

The Impact of Poverty

70. Much of the Committee’s consideration of child poverty has necessarily and appropriately concentrated on the assessment and evaluation of research and quantitative results on child poverty in Northern Ireland. The Committee, however, recognises that there is a very human side to the issue of child poverty.

71. For some children in the most severe poverty, the impact of poverty is in many ways a typical view of what we mean by poverty. Claire Linney, from Dungannon Borough Council[37], described the position of some families in severe poverty who are being supported by local charities.

In low income households, the priority is rent; the key thing is to keep a roof over one’s head. Charities visit households here and report to us what they find: cupboards with limited food, and food of poor nutritional value. People are reluctant to use energy for light, let alone heat. Even investors have told us that they have had to change heating systems because oil runs out regularly. Having paid such a high rent, people cannot afford the basics of life.

72. However, research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in Northern Ireland[38] indicates that the traditional perspective of child poverty, a child with no winter coat or without well-fitting shoes or eating fewer than three meals a day, although still a reality for some children, is not typical. The research goes on to argue that modern day poverty is in main not about the absence of material things, but rather is marked by real difficulties in paying for essential services or accumulating small financial assets or taking part in activities that the rest of society take for granted.

73. The Committee considered compelling evidence on wide range of impacts of poverty on children, from organisations such as NCH (NI)[39].

Poverty impacts on all aspects of a number of areas in a child’s life including Income (particularly for those living in families dependent on benefits or in low paid employment), Education (the impact of socio-economic disadvantage starts early and may continue throughout the child’s years of education, poor parents struggle to meet additional education costs), Health (along a range of indicators such as diet and nutrition, dental health, physical environment, emotional well being, stress and mental and sexual health), Home and neighbourhood (such as major increases in the number of homeless families presenting to the NIHE and high costs of heating) and Play and social development (going without play and safe places to go impacts on the quality of life of a child or young person).

74. Playboard[40] highlighted the limited opportunities for development through play, with 14% of children being unable to take part in a hobby or leisure activity and outlined the impact of deprivation of this nature on children’s behaviour and mental well-being.

75. Committee members were particularly struck by the evidence of Patricia Lewsley, the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People , in relation to the difficult choices that many poor families have to make[41].

A few weeks ago I met a teenager who was exceptionally good at art. For her mother to afford the art materials, they could either go without food for two days, or do without electricity for a day and a half. That girl had to make the decision. She felt that she could not put her mother in that position; therefore she chose another subject. That young person is subject to a poverty of opportunity.

76. A particular concern for the Committee in this period of rising food and fuel costs is the evidence from the Northern Ireland Anti-Poverty Network[42], that families experiencing poverty also face a much higher cost of living as they cannot access the credit or payment benefits more affluent people take for granted.

77. The Committee received evidence from a range of organisations, including the Southern and Eastern Health and Social Services Boards, the Institute of Public Health in Ireland and the Western Health Action Zone about the impact of poverty on children’s health. The Committee was advised that such impacts are evident even before birth and that the infant mortality rate in the most deprived fifth of local areas is one-third higher than in other local areas. The Committee’s attention was also drawn to the findings of the Bamford Review[43] which clearly highlight and illustrate the correlation between social deprivation and the prevalence of mental health difficulties.

78. The link between poverty and educational underachievement was also drawn to the Committee’s attention, both in the research considered by the Committee and during oral evidence. In written evidence to the Committee, the Department of Education[44] recognised the very powerful association between poverty and educational outcomes.

There is a strong correlation between social disadvantage and educational outcomes. Only 37.6% of school leavers entitled to Free School Meals achieved at least 5 GCSE grades A*-C or higher compared to 70.2% for those school leavers not entitled to Free School Meals. In those wards with high levels of disadvantage and low educational attainment the percentage of pupils achieving at least 5 GCSEs at A*-C can be as low as 23% compared to the average across all areas of 64%.

79. The Committee was keen to hear more directly about the experiences of young people in poverty and Save the Children and the University of Ulster agreed to provide the Committee with a briefing[45] on a number of research projects, including some as yet unpublished research, which involved children and young people offering their views on the impact of poverty on their lives.

80. The views of the young people substantiate much of the research presented to the Committee in that, whilst some children were concerned that families without much money wouldn’t be able to buy food, they also identified a number of wider impacts, including the potential for poorer children to be excluded from normal day to day activities such as after-school clubs, because they can’t afford to pay for them.

81. A very interesting finding from the research was that most of the children did not see themselves or their friends as living in families that ‘don’t have much money’, but they recognise migrant families as living in poverty.

82. The evidence considered by the Committee on the impact of child poverty provides a compelling human, social and economic case for eliminating child poverty to be a top priority for the Executive. In addition to the totally unacceptable reality of some children living in cold homes and unable to afford nutritious meals, there is the much more widespread impact of poverty on children’s health, education and safety and on their expectations and aspirations. Failure to address the impact of poverty on the aspirations and expectations of children has the potential to significantly limit the Executive’s ambitions for a highly educated and highly skilled workforce, supporting a high wage economy.

The Evidence-Base for the

Prevention of Child Poverty

83. In seeking to develop robust recommendations on the actions that need to be taken by OFMDFM and the Executive to deliver child poverty targets, the Committee has sought to develop an understanding of the causes of poverty, the factors that increase the likelihood of poverty, the factors that help to protect against poverty and the population groups at most risk of poverty. The Committee also commissioned research to investigate best practice internationally in tackling poverty and severe poverty.

84. International research[46] conducted by UNICEF identified four common factors which have the greatest impact on child poverty rates: unemployment; low wages; lone parenthood and level of social expenditure.