Session 2007/2008

First Report

Assembly and Executive review committee

Report on the Inquiry

into the Devolution of

Policing and Justice Matters

Volume 2

Written Submissions, Other Correspondence ,

Party Position Papers, Research Papers, Other Papers

Ordered by the Assembly and Executive Review Committee to be printed 26 February 2008

Report: 22/07/08R (Assembly and Executive Review Committee)

REPORT

EMBARGOED UNTIL

Commencement of the debate in Plenary on Tuesday, 11 March 2008

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Powers and Membership

Powers

The Assembly and Executive Review Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Section 29A and 29B of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and Standing Order 54 which provide for the Committee to:

- consider the operation of Sections 16A to 16C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and, in particular, whether to recommend that the Secretary of State should make an order amending that Act and any other enactment so far as may be necessary to secure that they have effect, as from the date of the election of the 2011 Assembly, as if the executive selection amendments had not been made;

- make a report to the Secretary of State, the Assembly and the Executive Committee, by no later than 1 May 2015, on the operation of Parts III and IV of the Northern Ireland Act 1998; and

- consider such other matters relating to the functioning of the Assembly or the Executive as may be referred to it by the Assembly.

Membership

The Committee has eleven members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson with a quorum of five. The membership of the Committee since its establishment in May 2007 has been as follows:

| Rt Hon Jeffrey Donaldson (Chairperson) | Mr Danny Kennedy |

| Mr Raymond McCartney (Deputy Chairperson) | Mr Nelson McCausland |

| Mr Alex Attwood | Mr Ian McCrea |

| Ms Carmel Hanna | Mr Alan McFarland |

| Ms Carál Ní Chuilín | Mr John O’Dowd |

| Mr George Robinson |

Contents

Volume 1

Executive Summary

Summary of Recommendations

Introduction

The Committee’s Approach

Issues, findings, recommendations and conclusions

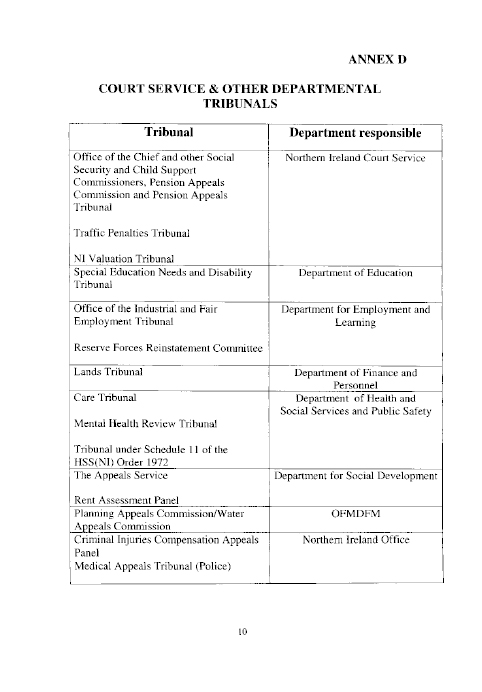

Annex A – Summary of what will devolve and what will not devolve

Appendicies

Appendix 1 – Minutes of Proceedings relating to the report

Appendix 2 – Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3 – Papers from the NIO

List of Witnesses

Volume 2

Appendix 4 – Written Submissions

Appendix 5 – Party Position Papers

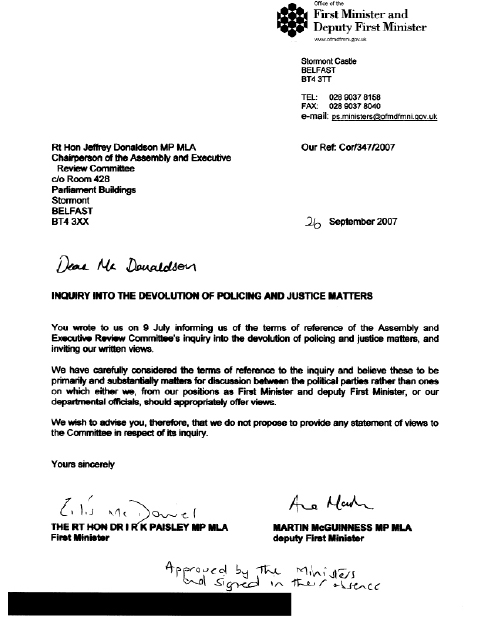

Appendix 6 – Other Correspondence

Appendix 7 – Research Papers

Appendix 8 – Other Papers

Appendix 4

Written Submissions

_fmt.jpeg)

Mr Stephen Graham

Clerk to Assembly and

Executive Review Committee

Room 428

Parliament Buildings

Stormont Estate

Belfast

BT4 3XX

Tel: (0)28 9052 1784

Fax: (0)28 9052 5917

Email: stephen.graham@niassembly.gov.uk

9 July 2007

Dear Sir/Madam

Inquiry into the devolution of policing and justice matters

The Northern Ireland Assembly has requested that the Assembly and Executive Review Committee should report on the work which needs to be undertaken in accordance with Section 18 of the Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006 in relation to the transfer of policing and justice matters. The Committee determined that it would proceed with this work by conducting a formal inquiry. The terms of reference for the inquiry are:

Terms of Reference

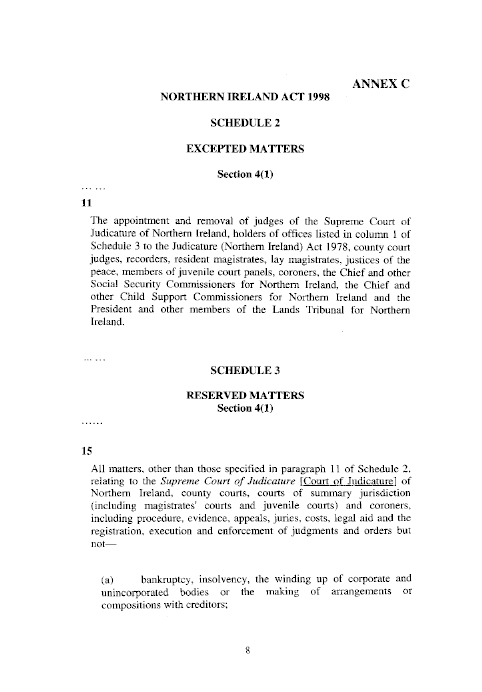

1. To identify those policing and justice matters which are currently reserved matters under Schedule 3 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (the 1998 Act);

2. To consider which of these matters should be devolved and the extent to which they should be devolved;

3. To identify the preferred ministerial model and procedures for filling the ministerial post/posts for the new policing and justice department;

4. To identify what preparations need to be made by the Northern Ireland Assembly to facilitate the devolution of policing and justice matters and what preparations have been made;

5. To assess whether the Assembly is likely to make a request under section 4 (2A) of the 1998 Act before 1 May 2008, as to which policing and justice matters should cease to be reserved matters; and

6. To report to the Assembly by 29 February 2008.

The Committee agreed as well as inviting submissions from organisations with a specific interest in policing and justice matters, your organisation might be interested in making a written submission which addresses the terms of reference outlined above. Should you wish to do so, please submit your response by e-mail to: committee.assembly&executivereview@niassembly.gov.uk.

Alternatively, as specified in the guidance enclosed 15 hard copies of your submission should be sent to The Committee Clerk, Mr Stephen Graham, Room 428, Parliament Buildings, Stormont, BT4 3XX.

The deadline for receipt of written submissions has been extended to 26 September 2007. Please note that any submissions received may be included in the Committee’s final report.

Please note that following receipt of any written submission you might make, you may be invited to present your submission at an oral evidence session with the Committee sometime during September/October/November 2007. Further information on the work of the Committee can be accessed on the following webpage:

http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/assem_exec/2007mandate/assem_exec.htm

If you have any queries, please get in touch with me on 028 9052 1784 or Roisin Donnelly on 028 9052 1845.

Yours faithfully

Stephen J Graham

Committee Clerk

List of Written Submissions

Committee on the Administration of Justice

Compensation Agency

Criminal Justice Inspection Northern Ireland

Disability Action

Down District Policing Partnership

Garda Síochána

HM Revenue and Customs

Include Youth

Legal Service Commission

Lord Chief Justice, Northern Ireland

Methodist Church in Ireland

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee

Northern Ireland Court Service

Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission

Northern Ireland Law Commission

Northern Ireland Office (Mr Paul Goggins MP)

Northern Ireland Policing Board

Northern Ireland Women’s European Platform

Presbyterian Church in Ireland

Probation Board for Northern Ireland

Police Service of Northern Ireland

Public Prosecution Service, Northern Ireland

Robert McCartney Justice Campaign

Serious Organised Crime Agency

The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland

The Irish Congress of Trade Unions

The Law Society of Northern Ireland

The Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform

The Scottish Government

Committee on the

Administration of Justice

Stephen J Graham

Clerk to the Assembly and Executive Review Committee

Room 428 Parliament Buildings

Stormont Estate

Belfast

BT4 3XX

3rd August 2007

Dear Mr Graham

Thank you for inviting the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) to make a written submission to the inquiry into the devolution of policing and justice matters. The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) was established in 1981 and is an independent non-governmental organisation affiliated to the International Federation of Human Rights. CAJ works on a broad range of human rights issues and its membership is drawn from across the community. CAJ’s activities include publishing reports, conducting research, holding conferences, monitoring, campaigning locally and internationally, individual casework and providing legal advice. Its areas of work are extensive and include policing, emergency laws, criminal justice, equality and the protection of rights. The organisation has been awarded several international human rights prizes, including the Reebok Human Rights Award and the Council of Europe Human Rights Prize.

As part of its work around policing and criminal justice, CAJ produced last year a major report on the devolution of criminal justice and policing powers to Northern Ireland. The report looks at models on offer from other jurisdictions and evaluates the advantages and disadvantages associated with each. Moreover, the report looks at other accountability mechanisms that need to be built into any system to ensure that power is administered fairly, effectively and in a human rights compliant manner. In addition, the report looks at the recent changes that have been taking place in criminal justice system in Northern Ireland as regards the impact they could have on devolution of power to the local level. Finally, it examines the issue of the delineation of powers to be devolved or retained at Westminster and the consequences this may have.

As such, we are very well placed to engage in this debate and we believe the content of our report will be extremely pertinent. In particular, chapter 2 on “governmental models for administering justice and policing functions” will be relevant for the discussions under point 3 of the inquiry’s terms of reference.

In relation to points 1 and 2 of the terms of reference concerning identification of matters which are currently reserved under Schedule 3 of the Northern Ireland Act and which of these should be devolved, this is a matter which CAJ believes is of crucial importance. We understand that some work was undertaken in relation to this by the sub-group on policing and justice matters of the Preparation for Government Committee last year. However, we believe that what is needed is a detailed examination of all the legislation that relates to criminal justice and policing matters in Northern Ireland in order to ascertain what power lies where and what exactly would be devolved. The Criminal Justice Review and Patten reports, and the various pieces of enacting legislation arising there from, contain various recommendations and sections imposing obligations and bestowing powers on the local administration, on Westminster and on the local administration post-devolution. The result is a distinct lack of clarity on who does what and when.

To take a concrete example, at the time of the passage of the legislation arising from the Patten report, much parliamentary concern was expressed about the appropriate relationship between the Secretary of State and the Policing Board. The conclusion at that time was that the Secretary of State should be given clear authority to override the decision of the Board in a number of respects.[1] Such primacy for the executive minister in Westminster was seen by many as problematic, but it might appear just as problematic, or even more so, if the “trump card” is in future held in the hands of a single locally elected minister. It is therefore essential that these powers should be re-examined in the context of future legislation to provide for the transfer of justice and policing powers to Northern Ireland.

The need for clarity is an issue that was also raised by the then Justice Oversight Commissioner who commented in his second report that:

“It would be useful for a study to be undertaken in advance of any devolution to identify the precise powers which would be transferred to the Northern Ireland Executive and what arrangements would be needed for their transfer.”

We therefore feel that a useful starting point for the Committee as it embarks on this inquiry would be to request such a detailed breakdown of powers from the Northern Ireland Office.

We enclose for circulation to the Committee copies of this covering letter and of the Executive Summary of this report, as well as a copy of the full report for you. Copies of the full report can be made available to all members of the Committee should you find this helpful. We would also be very keen to testify to the Committee should it decide to receive oral evidence, and we look forward to hearing from you in this regard.

Yours sincerely

Aideen Gilmore

Research & Policy Officer

[1] The Secretary of State can, for example, override a decision by the Board to hold an inquiry if s/he agrees with the Chief Constable that the Board’s request would: (a) interfere with national security interests; (b) relate to an individual and be of a sensitive personal nature; (c) likely to prejudice ongoing judicial proceedings; or (d) prejudice the detection of crime or apprehension/prosecution of offenders. See s. 59(3) and s.60(5) of Police (NI) Act 2000. Elsewhere, in s. 25(1)(a), the Secretary of State has a wide-ranging but relatively undefined power to issue “codes of practice relating to the discharge by the Board of any of its functions.”

Change and Devolution of Criminal Justice and Policing in Northern Ireland: International Lessons

Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ)

January 2006

Summary of Recommendations

1. CAJ takes no position on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and this report therefore takes no formal position on devolution within the UK context, nor does it address a series of issues around an all-Ireland relationship. These questions can and presumably will be addressed in the course of detailed negotiations between the various political parties and the British and Irish governments, in the context of discussions to date in the 1998 Agreement and the subsequent Joint Declaration (2003). At the same time, it is fair to say that the starting premise of this work was that in principle devolution of criminal justice and policing to more localised democratic control was to be welcomed, because it brings crucial decision making closer to those directly affected by those decisions. That said, our primary concern is that any eventual models of devolution be measured against clear human rights criteria, and that assessments of their relative merits and demerits be made on the basis of such criteria.

Any proposed devolution model needs to be assessed for its ability to:

- be open and transparent, so as to secure widespread public confidence;

- ensure an efficient and effective justice system;

- provide legal, democratic and financial accountability;

- represent the diversity that is Northern Ireland, and thereby ensure trust in its ability to work impartially and fairly for all; and

- deliver the administration of justice to the highest standards, as laid down in international and national human rights law.

2. CAJ recommends that the discussion about the appropriate devolution model to adopt should itself be an open and transparent debate, and should not be, or be seen to be, held behind closed doors and the subject to horse trading between different political parties. CAJ believes that the timetable for debate and for decision making is also a matter of public interest, rather than merely party political interest. It is particularly problematic that many changes recommended in the Criminal Justice Review are being treated (unjustifiably in our view) as contingent on devolution. Further foot-dragging of this kind can only fuel speculation that some of the Review recommendations are being held back so as to be treated as “bargaining chips” in the eventual political negotiations around devolution.

3. Regarding the appropriate governmental structures in any devolved criminal justice arrangements, CAJ concludes on the basis of its research that:

- a single department/minister may meet concerns about efficiency and effectiveness but may pose concerns around credibility and legitimacy in a politically polarised society like Northern Ireland. If it is determined to pursue a single ministry model, the emphasis will need to be on safeguards (such as those outlined in recommendation 4) that will ensure that the party ‘holding’ the single ministry is behaving in an impartial and non partisan way.

- a two or more departmental model would potentially offer Northern Ireland greater security against charges of ministerial partisanship since the departments can be headed up by members of different political traditions, who could be expected to act as a safeguard upon each other. This model risks being or appearing less efficient, and if pursued, the emphasis would need to be on mechanisms aimed at ensuring coordination, and collaboration across the criminal justice agencies will need to be the primary consideration.

- Northern Ireland already has the experience of the Office of the First and Deputy First Minister, which seeks to bring together cross-community ministerial responsibility within the operation of a single department, and some consideration was given to whether a similar model could be applied to a future Ministry of Justice. In reality, no other country studied had a model of this kind, so comparisons with elsewhere cannot be easily drawn upon. When learning from experience to date in Northern Ireland, it would appear that if this joint-leadership cross-community model were to be applied to criminal justice, it would be important to (i) have a clear delineation of responsibilities between the Minister and Deputy Minister (ii) establish clear protocols governing when joint agreement is needed and/or when a veto arrangement might operate and (iii) introduce a fall back mechanism to resolve any stalemates.

4. No executive governmental model (one, multiple, shared) is going to be self-sufficient in providing safeguards in such a highly contentious and politically problematic area. Northern Ireland should give active consideration to all of the following additional safeguards:

- Constitutional safeguards and Bills of Rights: a strong Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland will be an extremely important element of developing a criminal justice system that is both human rights compliant and sympathetic, and as such has a central role to play as an engine for transformation and change within criminal justice institutions.

- Parliamentary safeguards: tried and tested traditional methods of parliamentary scrutiny such as committees, questions and reporting obligations are extremely effective methods of holding minister(s) to account.

- Inspectorates/oversight mechanisms: such mechanism have already proved essential in monitoring the implementation of change in policing and criminal justice, and more permanent mechanisms should be considered.

- Complaints systems: while these are traditionally more common in relation to policing, the Criminal Justice Review recognised the importance of criminal justice institutions adopting procedures for complaints. Clearly the more independent these mechanisms are the better.

- Effective and independent judiciary: the judiciary must be in a position to rule objectively on the standards and human rights to which a member of the executive must adhere in the exercise of his or her ministerial responsibilities. Its established presence as an impartial and distinct organ of government should be a powerful deterrent to any justice minister who is tempted to act in a way which would be inconsistent with his or her office.

- Scrutiny at the local administrative level: the Criminal Justice Review envisaged a single local entity – building upon the Patten idea of District Policing Partnerships (DPPs) – which would deliver a holistic participatory approach to local policing and community safety. Government’s decision to run two local entities in tandem (DPPs and Community Safety Partnerships (CSPs)), with little coordination, seriously risks undermining the impact either body can hope to have.

- International scrutiny mechanisms: Government policy, the judiciary, the police, and all the criminal justice agencies, are obliged to comply with the international human rights standards that the authorities have freely signed up to.

- Civilian oversight and statutory commissions: bodies such as the NI Policing Board, Judicial Appointments Commission, Police Ombudsman and Criminal Justice Inspectorate will all be extremely important in monitoring the police and criminal justice institutions.

5. CAJ recommends that any major institutional change in criminal justice and policing be built upon a detailed programme of work which ensures that the new arrangements embrace change and commit to the principles such as openness, transparency, accountability and human rights as set out in recommendation 1 of the Criminal Justice Review.

In particular, CAJ notes that a number of the key recommendations from the Criminal Justice Review that are instrumental in bringing about such change have made the least progress in implementation. Institutional resistance to change, and the failure to fully embrace cultural transformation leads to serious questions about the ability of the criminal justice system to transform itself into one which commands the confidence of the community it serves. In particular, this report highlights how recommendations relating to securing a representative workforce, a more reflective judiciary, equity monitoring of those who pass through the criminal justice system, the policy around the giving of reasons for no prosecution, the implementation of complaints mechanisms, codes of ethics and discipline, and the provision of adequate and relevant human rights training have been most protracted in their implementation. CAJ notes that institutional and political resistance to deeper cultural change is evident in relation to these recommendations.

Without pressure for deeper institutional change, rebuilding confidence in the criminal justice system faces a tough challenge. At present it is difficult to see where such pressure exists. Arguably, the devolution of criminal justice and policing powers, and the local scrutiny and accountability that this will entail, could increase such pressure. Equally, however, failure to embrace the real and meaningful cultural change envisaged by the Criminal Justice Review could mean that other recommendations and reforms run the risk of becoming redundant, and indeed the devolution of criminal justice and policing powers would be of limited affect.

6. CAJ recommends that criminal justice only be devolved once there is a clear delineation of the exact powers that are to be ‘devolved’ and those that are to remain ‘excepted’. It is particularly important that there is clarity in the area of emergency powers and national security. There will be arguments as to whether to devolve more or less authority to locally elected bodies in these particularly contentious areas, but this must be determined in advance of the transfer of powers. It is extremely worrying that, despite several requests, the Northern Ireland Office has not complied with requests from CAJ and others to provide a factual list of the various powers, who holds them currently, and which of these powers might or might not be devolved in future. It is CAJ’s view that if there is ambiguity surrounding the nature and extent of authority and powers being transferred from Westminster to Northern Ireland, this would be very destabilising for the peace process, and could seriously undermine the efficiency and legitimacy of the eventual arrangements. Decisions underway currently, for example, regarding the transfer of key intelligence functions from the Police Service for Northern Ireland to MI5 will determine to a great extent the nature of criminal justice and policing powers to be devolved. In the past, problems of communication between internal branches of the police service – Special Branch and the regular units of either the RUC or PSNI – has led to grave errors (see, for example, the Ombudsman’s inquiry into the Omagh bombing). The transfer of some of these functions to an agency outside of the Police Service of Northern Ireland makes the likelihood of such errors more not less likely in future. Very importantly, it removes some key functions – ones which traditionally lend themselves most easily to abuses of human rights – from effective local oversight. A devolution of powers that is seen by people in Northern Ireland to be devolution in name only will only be counter-productive.

For further details or a copy of the report contact: CAJ, 45-47 Donegall St, Belfast, BT1 2BR; tel: 02890 961122; e-mail: info@caj.org.uk

Compensation Agency

17 July 2007

Inquiry into the devolution of policing and justice matters

Thank you for your letter of 9 July asking the Agency to give evidence to the Assembly and Executive Review Committee about the devolution of justice and policing functions. As an Executive Agency, we are part of the Northern Ireland Office and are accountable to Ministers there. As such, any response to your request would issue from NIO Ministers covering all of the Department.

I can, however, confirm that the discussion paper issued by the Government in February 2006 envisaged the transfer to the Northern Ireland Executive of all the functions falling in the reserve field currently undertaken by the Compensation Agency, and that remains our working assumption pending the outcome of the Assembly’s consideration.

I should mention that the Agency currently ministers, amongst its compensation schemes, one covering actions taken under the Terrorism Act. While the Act itself is not to be a devolved matter, I should envisage that the Agency will be asked to continue to administer the applications – which are now at a fairly low level – on the basis of a service level agreement.

Gareth Johnston

Chief Executive

Criminal Justice Inspection

Northern Ireland

Disability Action

Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

Disability Action’s Response

August 2007

Any enquiry concerning this document should be made to the

Office of the Chief Executive

Disability Action

189 Airport Road West

Belfast BT3 9ED

Tel: 028 90 297880

Fax: 028 90 297881

Textphone: 028 90 297882

Introduction

1 Disability Action is a pioneering Northern Ireland charity, working with and for people with disabilities. We work with our members to provide information, training, transport, awareness programmes and representation for people regardless of their disability; whether that is a physical, mental, sensory, hidden or learning disability.

2 More than one in five (300,000) people in Northern Ireland has a disability and the incidence is higher here than in the rest of the United Kingdom. Over one quarter of all families here are affected.

3 As a campaigning body, we work to bring about positive change to the social, economic and cultural life of people with disabilities and consequently our entire community.

4 Our range of services is provided from a Head Office based in Belfast and three local offices, with 85 staff and 250 volunteers.

5 Disability Action welcomes the opportunity to respond to this draft and to aid our response has put the relevant page/paragraph of the draft in brackets at the end of our comments.

General Commentary

2.1 Disability Action has recently established a Centre on Human Rights for Disabled People. The aim of the Centre is to secure the human rights of people with disabilities in Northern Ireland. Details of the Centre are enclosed for your perusal.

2.2 Disability Action welcomes the opportunity to make a written submission to the Northern Ireland Assembly Inquiry into the devolution of policing and justice matters. Disability Action is concerned with the interests of people with disabilities who whether they are victims of crime or perpetrators of crime.

3.0 The Rights of People with Disabilities

3.1 Disability has, until fairly recently, been an overlooked or ‘forgotten’ dimension of human rights[1]. Despite the existence of various human rights instruments at regional, European and international levels, people with disabilities continue to experience marginalisation, exclusion, disadvantage, and discriminatory assumptions about their quality of life. That is, people with disabilities are often subject to extensive human right violations.

3.2 The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (hereafter referred to as the Convention), and its optional protocol, was adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in New York on 13 December 2006. This Convention was signed by both the United Kingdom and Ireland at UN Headquarters on 30 March 2007, and is currently awaiting ratification by both States.

3.3 The international convention provides a major boost for disabled people’s human rights. The Convention obliges signatory States, which now include the UK and Ireland, to “promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.”

3.4 Disability Action wishes to direct the attention of the Executive to a number of articles contained within the Convention on the Rights of Disabled Persons which we feel are of particular significance to the present Inquiry:

- Article 5 requires States Parties to promote equality and prohibit all discrimination on the basis of disability

- Article 8 requires States Parties to foster respect for the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities and combat stereotypes, prejudices and harmful practices

- Article 10 requires States Parties to guarantee that persons with disabilities enjoy their inherent right to life on an equal basis with others

- Article 12 requires States Parties to ensure that persons with disabilities: have the right to recognition as persons before the law; that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life; and that State Parties take appropriate measures to provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity.

- Article 13 requires States Parties to ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others, including through the provision of procedural and age-appropriate accommodations, as witnesses, and in all legal proceedings, including at investigative and other preliminary stages. Article 13 further requires State Parties to promote appropriate training for those working in the field of the administration of justice, including police and prison staff.

- Article 15 requires States Parties to guarantee freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

- Article 21 requires States Parties to ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas on an equal basis with others and through all forms of communication of their choice

3.5 Disability Action urges the Executive to consider the forthcoming Convention as part of its Inquiry to ensure that, when ratified, Government’s obligations under the new Convention will be fully met.

4.0 Specific Commentary

4.1 There are currently no national statistics which can be drawn upon in relation to this issue. However, evidence, which we have outlined below, suggests that people with disabilities are more likely to be victims of certain crimes and anti-social behaviour compared to non-disabled people. Disability Action encourages the Executive Review Committee to actively address these issues when considering matters relating to the transfer of policing and justice.

4.2 The PSNI Statistical report shows that there were 70 incidents with a disability motivation reported to the PSNI, with 38 of these incidents recorded as crimes during the period 1 April 2005 – 31 March 2006. Twenty of the crimes recorded against disabled people during this period involved woundings or assaults. Criminal damage to property accounted for 9, theft 5, intimidation or harassment 3, and one recorded as ‘other violent crime’. There was little difference between urban and rural areas in terms of the types of crimes perpetrated apart from theft where there were 4 incidents recorded in urban areas compared with 1 in a rural area.

4.3 A study of 904 people with learning disabilities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, ‘Living in Fear’ ( Mencap 1999) found that nine out of ten respondents reported being bullied, harassed or intimidated and of these, almost a quarter reported physical attack. There have been incidents of attacks on people with disabilities that have attracted media publicity, but it is widely estimated that there is serious under-reporting of such crimes as disabled people believe their complaint will not be taken seriously by the authorities or by society in general.

4.4 A more recent survey of disabled people in Scotland found that 47% or respondents had experienced hate crime because of their disability and 31% of these people experience incidents regularly; at least once a month.[2] Where disabled people may have become accustomed to enduring verbal abuse on a regular basis, they may not be aware that they can, or should, report the incident to the PSNI. They may be so accustomed to such behaviour that they have almost ‘normalised’ it as part of their day to day experience and would not expect the PSNI to take the incident seriously.

4.5 In addition, disabled people, particularly those with learning disabilities or visual impairments, may also have difficulty identifying and giving evidence against their attacker. In some cases, disabled people see these attacks as extensions of society’s view of them as second-class citizens.

4. 6 Research by Mencap in 2002 shows that disabled people are four times more likely to experience sexual abuse than non-disabled people, and people with learning disabilities are particularly likely to experience this type of abuse.[3]

4.7 Children and young people with disabilities can experience bullying, intimidation and verbal abuse.

4.8 Under-reporting has repercussions. When incidents go unreported, the perception in society is that they are not taking place. To believe this is more ‘comfortable’ than the realisation that ‘this does happen here’ and that it needs to be addressed. Also, there is the danger that the perpetrators of hate crimes will believe their actions are acceptable if they are not being highlighted or condemned.

4.9 People with disabilities may also interact with the Criminal Justice System as prisoners, people who are on probation, on bail, or attending court or police stations. That someone has a disability does not mean they should not have the same rights and entitlements as people without disabilities.

4.10 A study by the Prison Reform Trust (2006) found that 70% of prison staff felt that they were not adequately trained to handle prisoners with disabilities, nor did they have enough time or staff.[4] The report also identified grave concerns about many prisoners’ lack of understanding of court proceedings and the prison system.

4.11 In Northern Ireland, the Bamford Report (2006) highlights the inadequacy of the existing criminal justice system in relation to treatment for people with a mental health disability.[5]

4.12 It is vital that people with disabilities who are in contact with the criminal justice system have access to accessible legal advice and representation. Disability Action is concerned that some people with disabilities experience extensive marginalisation and isolation in detention facilities due to a lack of accessible facilities, activities, and education programmes.

4.13 Lack of awareness of disabled people’s needs, and ineffective and unskilled communication with disabled people, further combine to exacerbate the social isolation and mental health issues that people with disabilities in the criminal justice system can experience.

4.14 Disability Action strongly recommends that the Executive acknowledge and address the following:

Limited knowledge of what constitutes a hate crime;

- Lack of accessible information;

- Lack of specialist support for victims;

- Lack of specialist support for perpetrators;

- Mistrust of the Criminal Justice System;

- Fear of intimidation;

- Fear of not being seen as a credible witness; and

- Lack of understanding of disability.

5.0 Conclusion

5.1 Disability Action has welcomed the opportunity to make a submission. Disability Action looks forward to continued dialogue on this and other issues of major significance to people with disabilities throughout Northern Ireland.

[1] R. Daw (2005) Human Rights and Disability: The Impact of the Human Rights Act on Disabled People, DRC/RNID

[2] Hate Crime Against Disabled People in Scotland – a survey report (2004) Capability Scotland and Disability Rights Commission.

[3] Behind Closed Doors (2002) Mencap: London

[4] Talbot, J. (2007) No one Knows: Identifying and supporting prisoners with learning difficulties and learning disabilities, Prison Reform Trust.

[5] Forensic Services (2006), The Bamford review of Mental Health and Learning Disability (Northern Ireland)

Down District Policing Partnership

In response to your letter regarding this issue please see the following response from Down District Policing Partnership;

- From a pragmatic point of view Down District Policing Partnership believes that all Justice and Policing Matters should be transferred to the Local Assembly

- The Ministerial Post involved should rotate between the Parties and should ensure the inclusive view-point of all opinion in Northern Ireland

- The Powers of the Minister should relate only to Long Term Strategic Decisions based on Patten and the follow-up to Patten

- The Devolution of the Ministerial Post should not in any manner interfere with the operational efficiency of Policing and Justice

If you should require any further clarification of DDPP Members views please do not hesitate to contact me at 028 44 610857 or by email at alan.mccay@downdc.gov.uk

With Regards

Alan McCay

Policing Partnership Manager

Garda Síochána

HM Revenue and Customs

Include Youth

Written Submission to the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive Review Committee Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

Table of Contents

Written Submission

Recommendations

Written Submission to the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive Review Committee Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

August 2007

Introduction

1. Include Youth promotes best practice with young people in need or at risk. We achieve this through the development and promotion of resources, the provision of training, information and support of practitioners and organisations. We also undertake activities aimed at influencing public policy and public awareness - locally and nationally.

2. Include Youth promotes the development of positive choices and opportunities for vulnerable and challenging young people in the community, residential care or custody. Include Youth promotes the use of community alternatives to care and custody for children and young people.

3. Amongst the young people at risk with whom, and on whose behalf, Include Youth works are young people from socially disadvantaged areas, those who have been truanting, suspended or expelled from school, those from a care background, young people who have committed or are at risk of committing crime, misusing drugs or alcohol, undertaking unsafe sexual behaviour or other harmful activities, or of being harmed themselves.

4. Include Youth runs the Young Voices project, which is a participation project for young people who have had experience of the criminal justice system, with the aim of supporting these young people to become involved in decision-making processes which impact upon their lives. Currently the Young Voices project supports young people in two groups – one drawing its members from the Greater Belfast area, and the second based in the Juvenile Justice Centre, Bangor.

5. In addition, Include Youth runs the YOYO Practitioners Forum, which draws together professionals from a range of statutory, voluntary and community organisations working directly with young people in need or at risk, and meets on a quarterly basis.

General Comments

6. Include Youth very much welcomes the opportunity to make written submissions to the Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters. Include Youth has a considerable track record of over 28 years working closely with all the relevant systems which engage with children at risk and in need. We have a sound understanding of child welfare, education and youth justice law, policy, practice and service delivery in Northern Ireland. We have a dedicated policy / advocacy role where we work to address all relevant issues concerning children and young people in conflict with the law. This work is informed by our work with young people, with practitioners as well as relevant human rights instruments and best practice evidence. As an organisation working to make children’s rights a reality in the most challenging of circumstances Include Youth is committed to working in partnership with all stakeholders in all settings.

7. Include Youth wishes to outline a number of general points in relation to the terms of reference. However, our submission focuses mainly on policing and justice matters and their impact on children and young people. We believe this Inquiry provides the Committee members with the opportunity to engage with the debate concerning children and young people at risk, particularly those in conflict with the law, in a positive and progressive way. This engagement should have significant positive impact on the lives of children, their families, the communities within which they live, together with the wider society.

Include Youth’s Vision for Youth Justice

8. Include Youth is currently working on producing a Vision for Youth Justice in Northern Ireland. Our intention is to provide a Framework for the development of a system for dealing with children in conflict with the law that is practical, realistic, achievable and children’s rights compliant. This Framework will focus on both ‘early intervention’ and the ‘formal youth justice system’. We intend to finalise this document early in the autumn and are keen to share it with members of the Committee. We believe it will be of significant assistance to members in their important deliberations regarding the devolution of policing and justice, especially where these issues relate to children and young people. However, we include below some initial findings from our work.

Terms of Reference

1. To identify those policing and justice matters which are currently reserved matters under Schedule 3 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (the 1998 Act);

9. We recognise that this is a broad and complex area which is demonstrated by the wide-ranging findings of previous reviews (e.g. Criminal Justice Review and the Patten Commission) and resulting legislation and reforms.

10. For the purposes of this submission, Include Youth will primarily address the reserved matters listed at Section 9, Schedule 3 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 in respect of how these impact upon children and young people.

11. One practical issue requiring clarification concerns where responsibility lies for the treatment in the community of children who offend (i.e. supervision of court ordered community sentences). At present there exists duplication of the roles of the Youth Justice Agency and Probation Board for Northern Ireland. As a matter of urgency Include Youth recommends the Committee seeks to resolve confusion over role of Youth Justice Agency and Probation Board for Northern Ireland regarding treatment in the community of children who offend.

2. To consider which of these matters should be devolved and the extent to which they should be devolved

12. Include Youth appreciates that devolving powers in respect of justice and policing matters is controversial and divisive. It will be essential to ensure that agreed measures will secure confidence of all sections of society. We welcome the Inquiry as an important step towards devolution of powers, as we believe that local democratic control brings crucial decision making closer to those directly affected by policy decisions and interventions. Within this context of democracy and devolution, it is imperative that proposed models of devolution are measured against unambiguous human rights criteria, and comply with international human rights and children’s rights standards.

13. Include Youth believes that youth justice should be devolved as soon as possible. Should the decision be taken to phase-in devolution of particular justice and policing powers, Include Youth strongly recommends that youth justice is processed in the first phase. In particular, we refer to the Youth Justice Agency of Northern Ireland (YJA) and its’ supporting NIO functions. Include Youth works closely with the YJA and in our view, there is nothing within its organisational structure to prevent early devolution. In our opinion the agency is professionally and ethically closer to (devolved) childcare systems than to any part of the criminal justice system. We believe that current administrative partnership arrangements with such bodies as the Public Prosecution Service or Northern Ireland Court Service could be maintained effectively should youth justice be devolved before other justice functions.

14. The majority of YJA staff are qualified as social workers, youth workers or teachers, and work from a child-centred value base. Moreover, the YJA is represented on a range of regional and sub-regional multi-agency forums that address issues relating to children at risk or in need. This recognises that children in conflict with the law are often also at risk in other contexts. As recent debates have highlighted[1], responses to young people in conflict with the law cannot be considered without recognising the broader circumstances of their lives; in particular, their social and economic situation, educational experiences and attainments, family life and alternative care, physical and mental health. Internationally it is recognised that children and young people at risk of committing crime or participating in anti-social behaviour are often those who leave school early, have a disability or special needs, live in poverty, have truanted or been excluded from school, have spent time in residential care or have experienced poor parenting.[2]

15. We recommend that the Committee requests access to as yet unpublished research into these issues. The research was commissioned by DHSSPS and NIO in 2005, entitled Pathways into Secure Care and was conducted by Independent Research Solutions.

16. Include Youth considers a holistic approach must be adopted in respect of all children, including those in conflict with the law, to ensure that the numerous and diverse problems they experience in everyday life can be identified, responded to and resolved in the best interests of the child. Central to this will be proper integration of policy, legislation, planning and delivery of services for all children and young people, and an integrated, multi-service approach by government which does not fragment and compartmentalize the lives of children into pre-ordained ‘silos’. Include Youth recommends that the early devolution of youth justice, along with other devolved children’s issues, should be set within the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and other international standards (including the Beijing Rules[3], Riyadh Guidelines[4], Tokyo Rules,[5] and the UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty). It should also take into consideration all relevant recommendations of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child.

3. To identify the preferred ministerial model and procedures for filling the ministerial post/posts for the new policing and justice department;

17. Include Youth is not convinced that placing youth justice within a new department of criminal justice and / or policing is appropriate or in the best interests of children, their families or the communities within which they live. Include Youth recommends that all issues relating to children in conflict with the law would be best located and progressed within an over-arching Department for Children and Young People, with its own Minister/Ministers and developed along a children’s rights - based model. Such a department should adopt an integrated, coherent multi-agency approach dealing with all aspects of children’s lives, including education, mental health, conflict with the law, public health, children requiring alternative care arrangements, anti-social behaviour, age appropriate play space etc. It is our strong view that placing youth justice within the criminal justice framework is ill-advised. It would continue to criminalise and further marginalise children already at risk who experience a range of complex issues and unmet needs as discussed above.

18. Additionally we strongly contend that a shift in emphasis away from criminal justice diminishes public protection. This has not happened in European States where the age of criminal responsibility is higher and the evidence suggests that a social justice emphasis enhances the safety of all citizens. Proper integration of children’s services means that early intervention, family support and preventative services will be better co-ordinated, as will provisions for those children who are deemed in need or at risk in the contexts of education, mental health or care. The Northern Ireland Children’s Strategy: Our Children and Young People – Our Pledge[6] outlines how services will be developed to meet six intended outcomes for all children and young people. These are:

- being healthy

- enjoying, learning and achieving

- living in safety and with stability

- experiencing economic and environmental well-being

- contributing positively to community and society

- living in a society which respects their rights

19. Include Youth asserts that, as these outcomes apply to all children and young people, including those in conflict with the law, they should provide the framework within which mainstream service provision can fulfil these functions.

20. We recommend that current powers within the Office of First Minister and Deputy First Minister should be extended in respect of their oversight function vis-à-vis other government departments obligations and duty of care to children and young people who fall within their jurisdiction, particularly in relation to the Outcomes identified in the Children’s Strategy.

21. With regards to the ministerial model, our preference is to locate all matters pertaining to children and young people within one department. We accept that this may be a long-term objective achieved incrementally. Nevertheless Include Youth believes that the speedy devolution of youth justice will be an important step towards a discrete department better serving the children and young people in NI and their communities. Include Youth would welcome the opportunity to provide further information and evidence to the Committee.

22. In the absence of a discrete Department for Children and Young People, how do we deal with current practicalities? Include Youth believes that structures for the devolution of youth justice - of the Youth Justice Agency - should emphasise the best practice approaches to children in conflict with the law outlined above, including redress to criminal justice systems as a matter of last resort. Include Youth respectfully suggests that the Committee recommends to the NI Assembly that youth justice be decoupled from the adult criminal justice process and located within a Ministry more geared towards the rights, care and welfare of children and young people.

23. In order to determine exactly where to place this brief, for example, within Department of Education, Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety, or OFMDFM – each of which currently has a clear brief in respect of certain aspect of children’s lives – Include Youth recommends that the Committee examines international best practice, including societies emerging from conflict. We believe it is imperative that to inform decisions regarding the devolution of youth justice, members of the Committee and the NI Assembly should have an understanding of the complex and often emotive nature of the key issues in the area of youth justice, alongside evidence of what works.

24. In the broader context of determining a ministerial model for the devolution of justice and policing more generally, we endorse research conducted by colleagues in the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) in 2006 entitled: ‘Change and Devolution of Criminal Justice and Policing in Northern Ireland: International Lessons’. This work examines the (i) single department/minister model, (ii) two or more departmental model or (iii) shared ministry within a single department.

25. As stated above, whichever model is agreed it must ensure compliance with international human rights and children’s rights standards. Crucial to this will be a range of safeguards, many of which have been outlined in some detail in the CAJ research.

4. To identify what preparations need to be made by the Northern Ireland Assembly to facilitate the devolution of policing and justice matters and what preparations have been made

26. Include Youth recommends that in preparation for the devolution of matters pertaining to youth justice, the NI Assembly should engage in a programme of information gathering, outreach and engagement with children and young people, families and communities. It is imperative that a thorough understanding is reached as to why children and young people become involved in offending behaviour which can often have devastating consequences on victims of crime, families, wider communities, not to mention the individual child or young person involved.

27. Whilst we appreciate that elected members spend considerable time speaking to and advocating on behalf of their constituents, we are also aware that many children and young people in conflict with law have had little or no direct experience of their elected representatives.

28. Include Youth’s Young Voices participation project recently underwent a very successful independent Evaluation[7], a copy of which is enclosed for your information, together with a Summary and Recommendations Document. The Evaluation demonstrates that it is possible to engage and enable the active participation of young people at risk, particularly those with experience of the criminal justice system, in public consultation initiatives, with very positive results.

29. Our experience of managing this process is that young people in conflict with the law have considerable, pertinent experience which they are eager to share when they feel listened to, valued and treated with respect. As one Young Voices participant stated: ‘People never listen to me – that’s what makes this different is that people in here listed to me and take on my views and asked me about why I did the things I did’ (page 24).

30. We believe that elected members would benefit significantly through direct engagement with young people in conflict with the law, as very often the prevalent media images of young people in securing eye-catching headlines. Media representation of the lives of children and young people serves to undermine them and their communities. Include Youth would be very keen to work with Committee members, and indeed more widely with colleagues in the Assembly, to help facilitate such a process of engagement through our Young Voices project.

31. ‘Before contact with the likes of Young Voices, we tapped into some groups in schools, community based groups etc. and the make up of these groups would vary – the Young Voices model gives us the opportunity to engage with the most hard to reach young people.’ Agency Representative, page 26

32. Additionally as mentioned above we believe that the Assembly will be assisted in their deliberations by accessing the international and local evidence concerning effective ways of preventing offending by children and young people and structuring services.

5. To assess whether the Assembly is likely to make a request under section 4 (2A) of the 1998 Act before 1 May 2008, as to which policing and justice matters should cease to be reserved matters

33. As stated, Include Youth identifies no barriers to the speedy devolution of youth justice once and appropriate and effective ministerial structure is agreed to ensure the best outcomes for children and young people, their families and communities.

Conclusion

34. Include Youth intends the above as a constructive submission, and we are keen to testify to the Committee should an oral submission be deemed helpful. Include Youth is committed to working in partnership with our colleagues in the NI Assembly. We request that we are kept fully informed of progress in relation to the Inquiry into the devolution of policing and justice matters, and look forward to the issues raised and recommendations made in this response being addressed and progressed.

Written Submission to the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive Review Committee Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

Recommendations

1. Include Youth recommends that proposed models of devolution are measured against unambiguous human rights criteria, and comply with international human rights and children’s rights standards.

2. Include Youth believes that youth justice should be devolved as soon as possible.

3. Include Youth recommends that all issues relating to children in conflict with the law would be best located and progressed within an over-arching Department for Children and Young People, with its own Minister/Ministers and developed along a children’s rights - based model.

4. In the absence of the immediate establishment of a Department for Children and Young People, Include Youth respectfully suggests that the Committee recommends to the NI Assembly that youth justice be decoupled from the adult criminal justice process and located within a Ministry more geared towards the rights, care and welfare of children and young people.

5. Include Youth considers a holistic approach must be adopted in respect of all children, including those in conflict with the law, to ensure that the numerous and diverse problems they experience in everyday life can be identified, responded to and resolved in the best interests of the child. Central to this will be proper integration of policy, legislation, planning and delivery of services for all children and young people, and an integrated, multi-service approach by government which does not fragment and compartmentalize the lives of children into pre-ordained ‘silos’.

6. We recommend that current powers within the Office of First Minister and Deputy First Minister should be extended in respect of their oversight function vis-à-vis other government departments obligations and duty of care to children and young people who fall within their jurisdiction, particularly in relation to the Outcomes identified in the Children’s Strategy.

7. Include Youth recommends that in preparation for the devolution of matters pertaining to youth justice, the NI Assembly should engage in a programme of information gathering, outreach and engagement with children and young people, families and communities.

8. As a matter of urgency Include Youth recommends the Committee seeks to resolve confusion over role of Youth Justice Agency and Probation Board for Northern Ireland regarding treatment in the community of children who offend.

9. We recommend that the Committee requests access to as yet unpublished research into youth justice issues. The research was commissioned by DHSSPS and NIO in 2005, entitled Pathways into Secure Care and was conducted by Independent Research Solutions.

[1] Davies, Z. and Mc Mahon, W. (Eds) (2007) Debating Youth Justice: from punishment to problem solving? Centre for Crime and Justice Studies

[2] Farrington, D.P. (2001) Risk-focused Prevention and Integrated Approaches in Pease, K. (Ed.) Reducing Offending. London: Home Office; and Youth Justice Board (2001) Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Youth Crime and Effective Interventions to Prevent It. Research Note No. 5, Chapter 4. Reducing Levels of Risk – What Works. London: Youth Justice Board

[3] United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice

[4] United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency

[5] United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures 1990

[6] OFMDFM (2006) Our Children and Young People – Our Pledge. A ten year strategy for children and young people in Northern Ireland 2006-2016, OFMDFM

[7] Green, R. (2007) Evaluation of Young Voices Project July 2004 – March 2007: ‘A Genuine and Authentic Voice for Children and Young People at Risk’ , Include Youth

Legal Services Commission

S.J. Graham Esq

Clerk to the Assembly and Executive Review Committee

Room 428

Parliament Buildings

Stormont

BELFAST

BT4 3XX

9 August 2007

Dear

Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

Introduction

I am replying to your letter of 9 July to Sir Anthony Holland in his capacity as Chairman of the Northern Ireland Legal Services Commission (the Commission). Sir Anthony’s term of office came to an end on 31 July 2007 and I have been appointed by the Lord Chancellor as the Interim Chairman until the substantive appointment of Chairman is made.

The Commission

The Commission was created on 1 November 2003 through the commencement of the Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2003. It has assumed responsibility for the provision of Legal Aid in Northern Ireland from the Legal Aid Department of the Law Society of Northern Ireland.

The Commission is a non departmental public body sponsored by the Northern Ireland Court Service (NICtS) which is answerable to the Lord Chancellor. The Northern Ireland Court Service funds-

1. the running costs of the Commission through a grant in aid, and

2. the expenditure of the Commission on criminal and civil legal aid through a grant.

Under the present arrangements-

1. the responsibility for policy development for criminal legal aid rests with the Northern Ireland Court Service, although the NICtS works closely with the Commission in developing proposals and administrative arrangements for criminal legal aid; and

2. the Commission has responsibility for administration and reform of civil legal aid and works closely with the NICtS as the sponsoring department in developing civil legal aid policy.

Devolution

The Commission would support the devolution of responsibility for policing and justice issues on a basis that can command respect and support across the community.

It believes that it is important that Northern Ireland has the discretion to develop the approaches to these policing and justice matters that are appropriate to its needs, drawing as is relevant on what happens in other jurisdictions.

If devolution of policing and justice issues is agreed, decisions in respect of legal aid will have to be made about-

1. whether the policy roles currently carried out by the NI Court Service in relation to legal aid should remain with the Court Service or whether these roles should pass to the new Department of Justice;

2. whether responsibility for all aspects of civil and criminal legal aid should be carried by one body, either the Commission or the Department, rather than being split between them; and

3. whether the NI Legal Services Commission should remain as a public body and be accountable to the new Department of Justice, or whether it should cease to be a public body with its responsibilities being taken over by the Department.

The Commission has, of course, a strong vested interest in the outcome and its preferences have to be viewed in that context. However, it offers the following points for consideration-

1. the devolution of responsibility for the core policing and justice responsibilities will be a very testing process for all involved and it might be sensible to minimise the changes on other related fronts;

2. it has been deemed appropriate to keep legal aid at arms length from government in both England and Wales and in Scotland and it would seem prudent to maintain that position in Northern Ireland;

3. the Commission has faced, and continues to face, serious difficulties in taking over responsibilities from the Law Society, improving the delivery of present services, and planning the reform of legal aid; ideally, it should be given the space to continue this work without fundamental disruption; and

4. at some point in time, responsibility for policy and execution in respect of civil and criminal legal aid must be brought together- at present the Commission has responsibility for paying out large sums of money for criminal legal aid without any control over who gets aid and how much; it might be sensible to resolve this at devolution rather than later.

Conclusion

The Commission recognises that, in the overall context of what your committee is considering, legal aid issues may not be a high priority.

However, we think that getting the legal aid arrangements right under devolution is important since-

1. legal aid consumes a lot of resources - the allocated running costs for the Commission in 2007/8 are approximately £7m while £65m is allocated to legal aid;

2. Ministers in a devolved executive will want to be confident that, on the devolution of responsibility,

a. appropriate funding is made available to meet existing and anticipated commitments;

b. legal aid merits this level of funding against all the other competing demands for resources, and

c. the arrangements in place are delivering value for money; and

3. the availability of legal aid is crucial to ensuring that people in need receive the help they need to secure access to justice. .

The Commission would be happy to provide the Committee with any further information in relation to criminal and civil legal aid that it might require to assist with its deliberations.

I hope that this submission is of assistance to the Committee.

Yours sincerely,

R B Spence

Interim Chairman

Legal Service Commission

S J Graham Esq

Clerk to the Assembly and Executive Review Committee

Room 428

Parliament Buildings

Stormont

BELFAST BT4 3XX

18 January 2008

Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

I am writing further to Ronnie Spence’s letter to you of 9 August 2007 about the implications for the Northern Ireland Legal Services Commission (the Commission) of the proposed devolution of policing and justice matters.

The Commission’s views remain as set out in the letter of 9 August. However, following a meeting with the Chair of the Assembly and Executive Review Committee on 10 January 2008, I thought that it might be helpful to draw the Committee’s attention to an additional point.

We understand that consideration is being given to the position of the Northern Ireland Court Service after devolution and, in particular, to whether it might be an agency of a Ministry of Justice or assume more of an arm’s length relationship with the Executive. This is not an issue on which the Commission wishes to express a view. However, it does have implications for the Commission, itself an “arm’s length” NDPB with the Northern Ireland Court Service as its sponsor department.

In a post devolution scenario we believe that consideration should be given to the Commission having a direct relationship with a Ministry of Justice as its sponsor department rather than with another arm’s length body. There are a number of factors that might support such a view:

- Short and clear lines of accountability.

- Easier to ensure that account is taken of the impact on legal aid (including its cost) when legislative and policy proposals are considered in the justice and other spheres.

- The major funding issues associated with legal aid will be more efficiently addressed if the Commission has a direct link with the responsible department.

- Better scope for developing shared back office services with other “justice” bodies.

On the other hand, the Northern Ireland Court Service has built up considerable expertise on legal aid matters which it would be detrimental to lose. If a decision were taken to shift sponsorship of the Commission from the Northern Ireland Court Service to a Ministry of Justice, then there would be a case for transferring the part of the Northern Ireland Court Service that sponsors the Commission into the Ministry.

I hope that the Committee finds these points helpful in its deliberations.

Yours sincerely

Jim Daniell

Chairman

Lord Chief Justice, Northern Ireland

Sent by e-mail

30 July 2007

Inquiry into the Devolution of Policing and Justice Matters

1. Thank you for your letter of 9 July 2007 to the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Brian Kerr. He has asked me to reply on his behalf. The Lord Chief Justice is grateful for the opportunity to comment on the devolution of those justice matters which impact on the judiciary. In providing his views he has asked me to emphasise that he recognises that, ordinarily, policy decisions are a matter for Government, however, in this case there will be aspects of change which will have such an effect on the judiciary that it is important for his views to feature large in the Committee and Assembly’s thinking. He will, of course, make himself available to meet the Committee if that would be helpful.

2. I should perhaps say at the outset that the Lord Chief Justice does not regard a number of the issues covered by the Committee’s terms of reference to be matters on which he should comment. There are others on which he has little to contribute. For instance on timing he thinks that all parties involved would welcome reasonable notice to enable preparation so that change is made as smoothly and efficiently as possible.

3. The Lord Chief Justice would like to comment on three main areas; safeguarding independence, judicial appointments and certain other matters which will be devolved and, related to the first point, the model for the Northern Ireland Court Service.

Safeguarding independence

4. The Lord Chief Justice became Head of the Judiciary in Northern Ireland, as well as President of the Courts, in April 2006 under Section 12(1) of the Justice (NI) Act 2002 as amended by Section 11 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. The Lord Chief Justice wants to emphasise the importance of judicial independence as a constitutional principle and the need for judges to be outside political influence. The United Nations Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary[1] state:

“1. The independence of the judiciary shall be guaranteed by the State and enshrined in the Constitution or the law of the country. It is the duty of all governmental and other institutions to respect and observe the independence of the judiciary …

4. There shall not be any inappropriate or unwarranted interference with the judicial process …”

5. This principle was recognised in the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 and the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 so that:

“3. Guarantee of continued judicial independence

(1) The Lord Chancellor, other Ministers of the Crown and all with responsibility for matters relating to the judiciary or otherwise to the administration of justice must uphold the continued independence of the judiciary.

(3) A person is not subject to the duty imposed by subsection (1) if he is subject to the duty imposed by section 1(1) of the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 (c. 26).

(4) The following particular duties are imposed for the purpose of upholding that independence.

(5) The Lord Chancellor and other Ministers of the Crown must not seek to influence particular judicial decisions through any special access to the judiciary.

(6) The Lord Chancellor must have regard to-

(a) the need to defend that independence;

(b) the need for the judiciary to have the support necessary to enable them to exercise their functions;

(c) the need for the public interest in regard to matters relating to the judiciary or otherwise to the administration of justice to be properly represented in decisions affecting those matters.

4. Guarantee of continued judicial independence: Northern Ireland

“….1 Guarantee of continued judicial independence

(1) The following persons must uphold the continued independence of the judiciary –

(a) the First Minister,

(b) the deputy First Minister,

(c) Northern Ireland Ministers, and

(d) all with responsibility for matters relating to the judiciary or otherwise to the administration of justice, where that responsibility is to be discharged only in or as regards Northern Ireland.

(2) The following particular duty is imposed for the purpose of upholding that independence.

(3) The First Minister, the deputy First Minister and Northern Ireland Ministers must not seek to influence particular judicial decisions through any special access to the judiciary.”

6. Section 6 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 also provides that the Lord Chief Justice may make representations to Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly. The provision in respect of the Assembly is as follows:

“(1) The Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland may lay before the Northern Ireland Assembly written representations on matters within subsection (2) that appear to him to be matters of importance relating to the judiciary, or otherwise to the administration of justice, in Northern Ireland.

(2) The matters are-

(a) excepted or reserved matters to which a Bill for an Act of the Northern Ireland Assembly relates;

(b) transferred matters within the legislative competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly, unless they are matters to which a Bill for an Act of Parliament relates.

(3) In subsection (2) references to excepted, reserved and transferred matters have the meaning given by section 4(1) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.”

7. This provision will enable the Lord Chief Justice to make written representations on certain matters that relate to the judiciary or the administration of justice in Northern Ireland. The Lord Chief Justice sees this as an important provision given his role as Head of the Judiciary in Northern Ireland.

8. He regards it as essential that Government Departments[2] generally, but especially the new Ministry of Justice (whatever its title), should consult the judiciary (through the Lord Chief Justice’s Office) on any proposals which will have an impact, either directly or indirectly, on the judiciary. The Lord Chief Justice thinks it essential for this message to be emphasised at the outset for the new Ministry.

9. The Lord Chief Justice also anticipates that he and the new Minister(s) for Justice will need to have an effective working relationship which would be supported by periodic meetings. The different roles and responsibilities need to be recognised, and clearly he cannot engage on individual cases, but he is willing to develop such a relationship.

Appointments and other significant issues being transferred

10. Under the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002, as amended, the Lord Chancellor remains responsible for certain issues impacting on the judiciary in Northern Ireland (and England and Wales). These include the determination of judges’ remuneration and other matters concerning terms and conditions of service. Some of his other responsibilities, however, will transfer to the First Minister and deputy First Minister or the Minister of Justice. The principal ones of these which the Lord Chief Justice would like to highlight are judicial appointments, the duty to ensure that there is an efficient and effective system to support the carrying on of the business of the courts in Northern Ireland and that appropriate services are provided for those courts (Section 68A of the Judicature (NI) Act 1978)[3].

11. At present, in most cases, the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission makes recommendations for appointments to judicial offices listed at Schedule 1 to the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002, as amended, to the Lord Chancellor. On devolution of justice these recommendations will be made to the First Minister and deputy First Minister (with some variation of more senior appointments). They must act jointly in considering them. The Commission is also required to give the First Minister and deputy First Minister advice on the procedure to be adopted for appointments of the Lord Chief Justice or a Lord Justice.

12. The Chairman of the Judicial Appointments Commission is the Lord Chief Justice. The Commission itself comprises five independent members, two from the legal professions and five members of the judiciary in addition to the Chairman. It has a statutory duty to make appointments on merit alone, but these should, so far as is reasonably practical, be such that those holding listed judicial offices are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland. The Commission is also required to engage in a programme of action designed to secure, so far as is reasonably practical to do so, that appointments are listed to judicial officers as such that those holding such offices are reflective of the community.