Session 2007/2008

First Report

The Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Report into Renewable Energy and Alternative Land Use

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee relating

to the Report, Minutes of Evidence and written submissions

Ordered by the Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development to be printed 24 June 2008

Report: 39/07/08R (Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development)

PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY

BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development is a Statutory Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 46. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department for Agriculture and Rural Development and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental Budgets and Annual Plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of relevant primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for Agriculture and Rural Development.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five members. The membership of the Committee is as follows:

Dr William McCrea MP MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr PJ Bradley

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Thomas Burns

Mr Trevor Clarke

Mr Willie Clarke

Mr Pat Doherty *

Mr William Irwin

Mr Francie Molloy

Mr George Savage

* Mr Pat Doherty replaced Mr Gerry McHugh with effect from the 21st January 2008.

Table of Contents

Report

Inquiry Aim and Terms of Reference

Approach

Summary of Recommendations

Findings and Recommendations

Statutory Progress

Dard Renewables Action Plan

Opportunities For Farm And Rural Businesses

Market Certainty

Business Market Focus

Non-Wind Renewable Energy

Anaerobic Digestion

Strategic Support

Cross-Departmental Monitoring

Additional Recommendations

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3: Written Submissions

Action Renewables

Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute

Allied Biodiesel Industries

B9 Organic Energy

Carbon Trust

Committee of Culture, Arts and Leisure

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

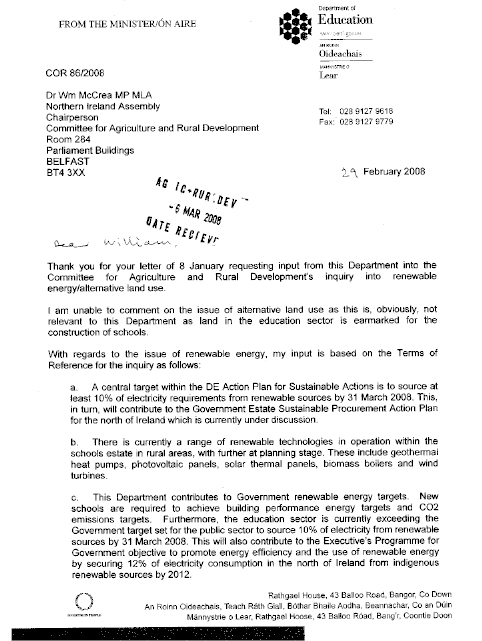

Department of Education

Department for Employment and Learning

Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

Department of Environment

Department of Finance and Personnel

Farm Woodlands

Green Energy Ltd

Home Energy Conservation Authority

Mr JWI Duff

Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulator

Northern Bio Energy Ltd

Northern Ireland Energy Agency

Northern Ireland Environment Link

Powertech Ltd

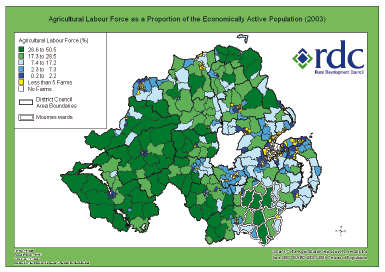

Rural Development Council

Rural Generation Limited

Sustainable Energy Association

Ulster Farmers’ Union

Woodland Trust

WWF Northern Ireland

Inquiry Aim and Terms of Reference

1. The Committee agreed the aim and terms of reference at its meeting of 29 November 2007 in the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise, Enniskillen Campus. These were agreed as follows:

Aim

“To establish the potential economic benefits Northern Ireland family farm and rural businesses could derive from renewable energy and alternative land uses relative to existing land use and agricultural practices, the potential agricultural and environmental effects of any such changes and to what degree renewables should become a focus of DARD resourcing relative to other agri-rural objectives.”

Terms of Reference

a) The recent and current policy framework for the development of renewable energy in Northern Ireland, focussing on but not limited to those policies developed and implemented by DARD;

b) The range of renewable technologies currently in operation or planned in rural communities, taking into account, as appropriate, similar projects elsewhere;

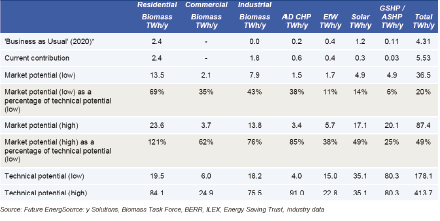

c) The relative importance in terms of contributing to Governments renewable energy targets, of heat from renewable sources, electricity from renewable sources and fuel from renewable sources, and how relevant each could be to the NI economy;

d) The range of support available to renewable initiatives at local, national and European levels;

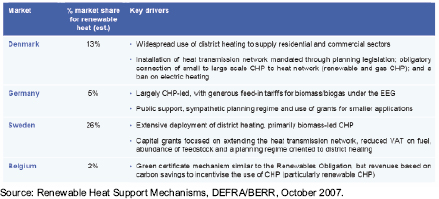

e) To compare the range of fiscal and other incentives offered elsewhere to support the development of a renewable energy industry and the infrastructure to support it;

f) The potential role of farm and rural businesses and rural communities in the delivery of a renewables programme which contributes to the sustainability of those business and the wider community; and

g) The ways by which the Department for Agriculture and Rural Development could implement and resource a renewable energy programme in a manner which contributes to the sustainability of the agricultural/rural sector and contributes to Northern Ireland’s renewable energy targets.

Approach

2. The Committee agreed to the placing of a public advertisement on 29 November 2007. In total, the Committee was pleased to receive 26 written submissions to the inquiry. These are contained in Appendix 3.

3. The Committee also agreed that a special advisor should be appointed to aid the Committee in its considerations of the subject area. Mr Jim Kitchen, Head of Sustainable Development Commission NI was appointed following the Committee meeting of 26 February 2008.

4. Following consultation with the special advisor, the Committee agreed on 8 April 2008 to receive oral evidence from the following 11 contributors:

- Action Renewables

- Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (Hillsborough)

- Carbon Trust

- Department for Agriculture and Rural Development

- Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

- Mr Ian Duff

- Northern Ireland Energy Link

- Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulator

- Sustainable Energy Association

- Ulster Farmers Union

- World Wildlife Fund Northern Ireland

5. The Committee received evidence from the above over three full days, including one held at the Agri-Food and Biosciences site at Hillsborough, Co. Down.

6. The Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development would wish, at this stage, to record their thanks to all those who participated in the inquiry through the provision of written and oral evidence.

Summary of Recommendations

7. The Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development makes the following recommendations:

(a) On publication of the Department for Enterprise, Trade and Investment Bio-energy report, both DETI and DARD should examine it along with this report for areas of complementarity;

(b) Government needs to seriously address the actions needed in order to achieve the PSA target of 12%. This should be addressed urgently;

(c) The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development should devise realistic timelines for the implementation of the Renewables Action Plan. This timeline should include key challenging and measurable targets for the achievement of outputs;

(d) The Department should address, as a matter of urgency, the legal status of the Agri-Food Waste Challenge Fund and the match funding element of the £10 million renewables programme. The Department should also exploit potential funding available through the European Union;

(e) The Department needs to identify and communicate specific renewable energy funding programmes available through the Northern Ireland Rural Development programme rather than generic measures that may or may not provide funding. Again, this should be undertaken as a matter of urgency;

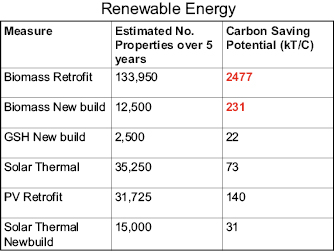

(f) The Executive should increase the use of biomass as an energy source, introducing a hierarchy of its use. There is widespread agreement that the best use of biomass is for heating, replacing fossil fuels. Below that in the hierarchy comes electricity generation and finally liquid bio fuels, the least carbon-efficient use of biomass;

(g) Public sector procurement should favour biomass heating solutions, helping to create the market demand to stimulate the industry. Such a commitment would be aligned with the Government’s climate change and sustainable development objectives;

(h) Measures in the three axes of the North Ireland Rural Development Programme should be used to facilitate the establishment of ESCOs (or similar vehicles). The NIRDP could also support training in the necessary business practices to set up the companies, develop proposals, negotiate contracts with end users and promote the widespread adoption of successful small-scale RE business models;

(i) The Committee believes that the Executive should be pro-active in its support for low-carbon innovation, being prepared to challenge its own aversion to risk in its support for the development of renewable energy schemes The Executive should review current funding schemes and consider successor funding to ensure the ongoing development of the non-wind renewable energy sector;

(j) The Committee recommends continued and, where necessary, enhanced support for research on farm-scale anaerobic digestion trials. In addition, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development and the Department of the Environment should explore whether the use of anaerobic digestion could be used as support for a case to extending the derogation on the Nitrates Directive and as a positive means of achieving compliance with the Directive;

(k) The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development should establish a (virtual) Centre of Renewable Energy Excellence to capture the benefits of the work being undertaken in Northern Ireland and to introduce best practice within a rural context. This could also include a non-food crops centre for Northern Ireland to link research to production and on to market;

(l) The cross-Departmental group on bio-energy, led by DETI, should report on a quarterly basis on its progress and that of the Executive in making progress towards its targets on the adoption of renewable energy. The Executive may also wish to consider establishing an external monitoring group, like the NI Biodiversity Group, to monitor progress;

(m) A key objective for DARD should be to increase the exploitation of RE opportunities;

(n) Northern Ireland has enormous potential to participate in the RE sector, especially by the agricultural industry. This potential should be exploited;

(o) There should be a review of the Northern Ireland energy strategy, including a legal regime for heat;

(p) Short Rotation Coppice Willow is a very effective crop for bio-remediation, which also makes its production economically attractive. The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development, and other relevant Executive departments, should develop the mechanisms to deliver planned production;

(q) Northern Ireland building regulations should be revised to promote the use of renewable energy technologies in all buildings;

(r) Planning Service needs to be more facilitative of small-scale planning renewable energy technologies; and

(s) Energy is a legitimate concern of many Assembly Committees and should not be reserved by the ETI Committee.

Findings and Recommendations

Statutory Progress

8. The Committee Inquiry coincided with a period that has seen fuel costs escalate to all-time highs and with the threat of prices increasing by up to 40% over the next year. It has also coincided with a period that has seen sustained pressures on the agricultural sector that have been exacerbated by high energy costs.

9. Overall, the Committee was pleased with the standard of the majority of the presentations. It was disappointed, however, that the statutory sector had not made the progress it would have hoped, with the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment Bio-energy study, originally scheduled for March 2008, now not available until the later summer. Recommendations have been made, therefore, in the absence of this report and the Committee recognises that the outputs deriving from the study may well have an impact on these.

10. The Committee noted that the government departments participated in a number of cross-sectoral working groups. However, the Committee was concerned that these groups appeared to prefer establishing research into renewable proposals rather than endorse actions to implement them. The Committee would be concerned that, as a result of this perceived inaction, the Executive targets of 12% of energy deriving from the renewable sector will not be achieved.

Recommendation

On publication of the Department for Enterprise, Trade and Investment Bio-energy report, both DETI and DARD should examine it along with this report for areas of complementarity.

Government needs to seriously address the actions needed in order to achieve the PSA target of 12%. This should be addressed urgently.

DARD Renewables Action Plan

11. The Committee was particularly disappointed with the oral presentation provided by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD). Whilst the Committee recognises and encourages the research being undertaken by the College for Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) and at the Agri-food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) at Hillsborough, the Committee was disappointed to learn that the Department’s Action plan had not progressed in the first 15 months of its existence. The Department also apprised the Committee that they were “still establishing whether, under current legislation, it has permission to legally create the [Agri-Food Waste] challenge fund”[1]. This despite having announced the fund some 15 months previously.

12. Additionally, the Committee learned that the £10 million renewables programme announced by the Department had not progressed at all. Indeed, there was the belief that this had actually retreated whenever the Department apprised the Committee that the match funding element for the programme, £5 million, had only recently been applied for and had not, at the time of writing, been secured. The Committee was extremely disappointed to learn that the only substantive bid for resources actually secured was for £2.55 million from DFP for the next three years under the Chancellor’s innovation fund.

13. The Committee also heard that funding for renewable energy projects was available under the Northern Ireland Rural Development Plan 2007 – 2011.[2] However, it was not evident under which measures this funding was available. Unfortunately, the delay in actually progressing the renewable energy action plan is replicated by delays in implementing the Rural Development Programme.

Recommendation

The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development should devise realistic timelines for the implementation of the Renewables Action Plan. This timeline should include key challenging and measurable targets for the achievement of outputs.

The Department should address, as a matter of urgency, the legal status of the Agri-Food Waste Challenge Fund and the match funding element of the £10 million renewables programme. The Department should also exploit potential funding available through the European Union.

Finally, the Department needs to identify and communicate specific renewable energy funding programmes available through the Northern Ireland Rural Development programme rather than generic measures that may or may not provide funding. Again, this should be undertaken as a matter of urgency.

Opportunities for Farm and Rural Businesses

14. The Committee found that there was a lack of focus on the opportunities for family farms and rural businesses in the development of renewable energy with most of the attention, investment and fiscal support being for large-scale wind developments. DETI’s Bio-Energy research may lead to a policy change which will begin to address this imbalance, which will be necessary in meeting their non-wind component of their 2012 target. Locally produced Bio-energy can only ever produce a small (but significant) proportion of Northern Ireland’s energy needs.

Recommendation

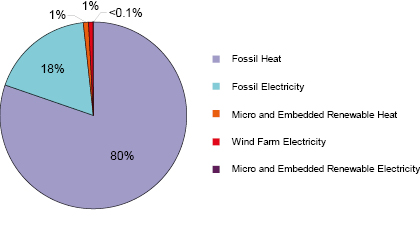

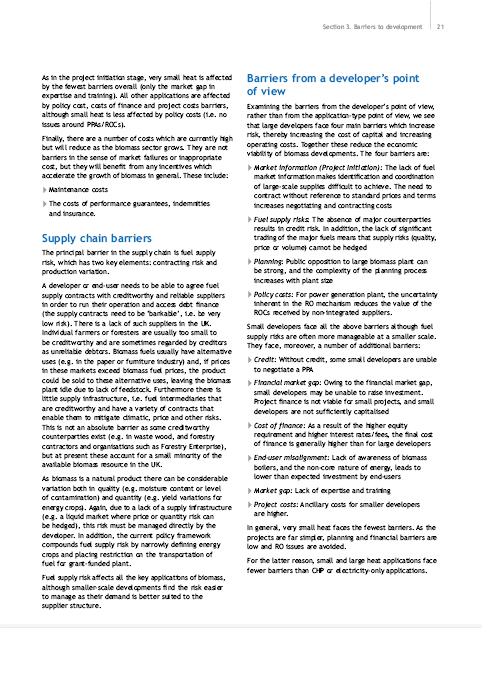

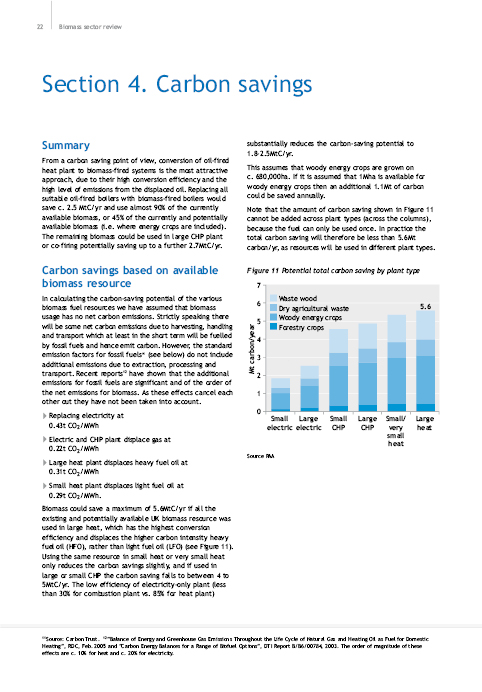

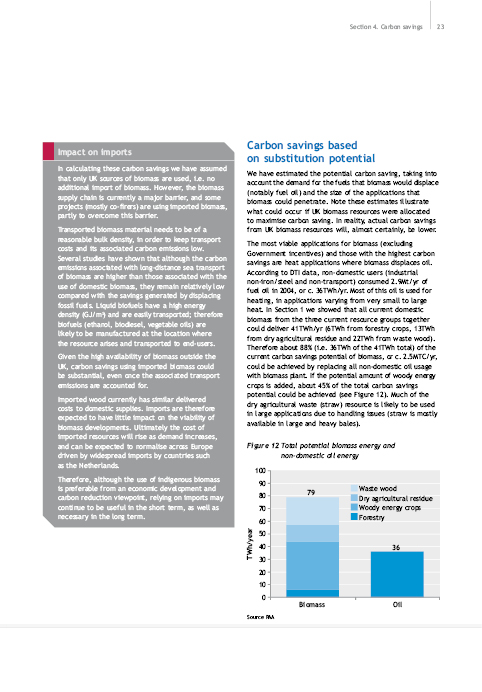

The Executive should increase the use of biomass as an energy source, introducing a hierarchy of its use. There is widespread agreement that the best use of biomass is for heating, replacing fossil fuels.[3] Below that in the hierarchy comes electricity generation and finally liquid biofuels, the least carbon-efficient use of biomass.

Market Certainty

15. Rural businesses need more certainty of the market if they are to invest in the bio-energy sector; lack of confidence in the supply chain is a major barrier in the renewable energy sector. Farmers’ long-term commitment to energy crops needs the support of secure market demand.[4]

Recommendation

Public sector procurement should favour biomass heating solutions, helping to create the market demand to stimulate the industry. Such a commitment would be aligned with the Government’s climate change and sustainable development objectives.[5]

Business Planning Focus

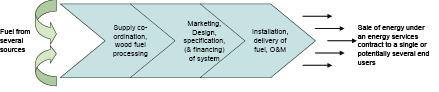

16. Small renewable energy enterprises should focus their business planning towards the goal of delivering heat, not biomass, moving their production up the value chain. This may best be delivered by groups of farmers, rather than an individual, by creating Energy Supply Companies (ESCOs) or ‘heat entrepreneurs’.[6] The Department is asked to note that Action Renewables has submitted a report on the establishment of ESCOs to the Department for Enterprise, Trade and Investment.

Recommendation

Measures in the three axes of the North Ireland Rural Development Programme should be used to facilitate the establishment of ESCOs (or similar vehicles). The NIRDP could also support training in the necessary business practices to set up the companies, develop proposals, negotiate contracts with end users and promote the widespread adoption of successful small-scale RE business models. [7]

Non-Wind Renewable Energy

17. Non-wind renewable energy generation is an immature industry, at its earliest stages in Northern Ireland. In time, it is likely to develop through market demand, when consumers have confidence in the technologies and as fossil fuels rise in price and decline in availability. Experience from the wind industry demonstrates the importance of Government subsidies and support in the early stages of development and, indeed, the Stern Review highlighted the role of publicly-funded research and development. The Committee received a variety of proposals in submissions, ranging from changing the Renewables Obligation Certificates system, through establishing a low-interest community loan system, to introducing renewable heat grants. It was not possible for the Committee to determine the relative merits of these proposals without much more detailed consideration. There was, however, widespread support for the re-establishment of the discontinued Reconnect programme of DETI’s Environment and Renewable Energy Fund.

Recommendation

The Committee believes that the Executive should be pro-active in its support for low-carbon innovation, being prepared to challenge its own aversion to risk in its support for the development of renewable energy schemes The Executive should review current funding schemes and consider successor funding to ensure the ongoing development of the non-wind renewable energy sector.[8]

Anaerobic Digestion

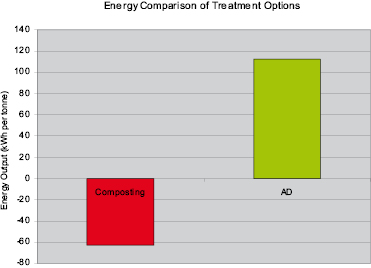

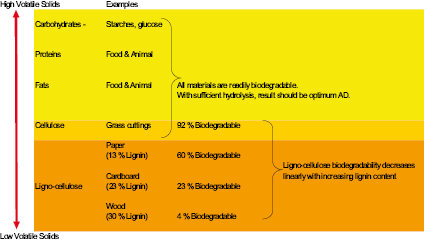

18. Anaerobic digestion is a specific technology offering potentially significant benefits to rural business. It may help to solve the problem of excessive amounts of nutrient-rich farm waste, while generating useful dispatchable energy. The evidence was divided on whether the best way forward was for a limited number of centralised plants[9] or a dispersed regime of farm-scale digesters.[10] One larger-scale plant is likely to open by the end of 2009.

19. The evidence received by the Committee suggests that more research is necessary on the likely costs and benefits of farm-scale digesters in Northern Ireland. DARD’s proposed Agri-Food Waste Challenge Fund may help to stimulate further work on anaerobic digestion (see para. 13).

Recommendation

The Committee recommends continued and, where necessary, enhanced support for research on farm-scale anaerobic digestion trials. In addition, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development and the Department of the Environment should explore whether the use of anaerobic digestion could be used as support for a case to extending the derogation on the Nitrates Directive and as a positive means of achieving compliance with the Directive.

Strategic Support

20. The immaturity of the development of many of these renewable energy technologies suggests that it may be some years before their commercial application is taken up by many small businesses, other than the few early-adopting ‘pioneers’ in Northern Ireland. Nevertheless, that suggests a role for the Government in redoubling its efforts to provide strategic support for this embryonic industry. There is much of value on which to build – some world-class research at the universities and at AFBI, a range of commercial companies investing in the sector here and a budding demand for some of the technologies, as demonstrated by the high demand for EREF Reconnect funding.

Recommendation

The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development should establish a (virtual) Centre of Renewable Energy Excellence to capture the benefits of the work being undertaken in Northern Ireland and to introduce best practice within a rural context. This could also include a non-food crops centre for Northern Ireland to link research to production and on to market.[11]

Cross-departmental Monitoring

21. As previously stated, the Committee was concerned at the perceived lack of progress being made by government bodies. There was a perception among stakeholders that working groups established by government were little more than “talking shops” and that no real actions were being delivered or communicated.

Recommendation

The cross-Departmental group on bio-energy, led by DETI, should report on a quarterly basis on its progress and that of the Executive in making progress towards its targets on the adoption of renewable energy. The Executive may also wish to consider establishing an external monitoring group, like the NI Biodiversity Group, to monitor progress.[12]

Additional Recommendations

22. The Committee also received a number of suggested actions from witnesses which the Committee believes merits inclusion and which it recommends to the relevant bodies for consideration and implementation. These are detailed below.

Recommendations

A key objective for DARD should be to increase the exploitation of RE opportunities.[13]

Northern Ireland has enormous potential to participate in the RE sector, especially by the agricultural industry. This potential should be exploited.[14]

There should be a review of the Northern Ireland energy strategy, including a legal regime for heat. [15]Short Rotation Coppice Willow is a very effective crop for bio-remediation, which also makes its production economically attractive. The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development, and other relevant Executive departments, should develop the mechanisms to deliver planned production.[16]

Northern Ireland building regulations should be revised to promote the use of renewable energy technologies in all buildings.[17]

Planning Service needs to be more facilitative of small-scale planning renewable energy technologies.[18]

Energy is a legitimate concern of many Assembly Committees and should not be reserved by the ETI Committee.[19]

Renewable Energy schemes must be based on sound science, sustainable and carbon-justified, as well as economically viable.[20]

[1] Official Report, 24th April 2008

[2] http://www.dardni.gov.uk/index/publications/pubs-dard-rural-development/

[3] Carbon Trust, NI Authority for Utility Regulator, DETI, DARD, WWF et al

[4] AFBI, Ian Duff, Carbon Trust, Sustainable Energy Association et al

[5] Carbon Trust, DARD, Ian Duff et al

[6] AFBI, Action Renewables, Ian Duff et al

[7] Action Renewables, AFBI, Ian Duff , WWF et al

[8] Action Renewables, NI Authority for Utility Regulator, Sustainable Energy Association, WWF et al

[9] B9, Carbon Trust

[10] AFBI, , the Ulster Farmers Union, WWF et al

[11] Ulster Farmers Union

[12] Ulster Farmers Union

[13] DARD

[14] NI Authority for Utility Regulator

[15] NI Authority for Utility Regulator

[16] AFBI

[17] Action Renewables

[18] Sustainable Energy Association

[19] NI Environment Link

[20] AFBI

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

of the Committee Relating

to the Report

Thursday 29 November 2007

Conference Room, Cafre, Enniskillen

Present:

Dr William McCrea MP (Chairperson)

Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Thomas Burns

Willie Clarke

Trevor Clarke

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Jim Beatty (Assistant Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Kathy Neill (Clerical Officer)

Apologies:

William Irwin,

Gerry McHugh

The meeting opened at 1.04pm in Public Session.

1. Apologies

As above.

2. Committee Inquiry

The Committee agreed the aims and Terms of Reference, a Forward Work Programme for delivery of the inquiry and a press notice which will also be inserted into periodicals as well as the local newspapers. It was agreed that the Committee would use the services of a specialist advisor, if necessary.

The meeting was adjourned at 4.00pm.

[Extract]

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Tuesday 26 February 2008

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Dr William McCrea MP (Chairperson)

Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Thomas Burns

Trevor Clarke

Willie Clarke

Pat Doherty

William Irwin

Francie Molloy

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Kathy Neill (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: None

The meeting opened at 1.30pm in Public Session.

1. Apologies

As above.

2. Committee Inquiry

The Committee agreed that Mr Jim Kitchen, Head of Sustainable Development Commission NI, would be appointed as the Committee’s Special Advisor into their inquiry into Renewable Energy and Alternative Land Use.

The meeting was adjourned at 4.15pm.

[Extract]

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Tuesday 8 April 2008

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Dr William McCrea (Chairperson)

Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Trevor Clarke

William Clarke

Pat Doherty

William Irwin

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Andrew Dibden (Clerical Officer)

Apologies:

Thomas Burns

The meeting opened at 1.35pm in Public Session.

1. Apologies

As above.

2. Committee Inquiry

Jim Kitchen, the Committee’s Specialist advisor, joined the meeting at 4.25pm and briefed the Committee on all written submissions for the Committee’s inquiry into ‘Renewable Energy and Alternative Land Uses’. He then gave his recommendations on which groups should be called for Oral Evidence. The Committee agreed to his recommendations and he left the meeting at 4.35pm.

The meeting was adjourned at 4.38pm.

[Extract]

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Thursday, 24 April 2008

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Dr William McCrea MP (Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Trevor Clarke

Willie Clarke

William Irwin

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Jonathan Young (Clerical Officer)

The Chairperson opened the public meeting at 10.15am.

1. Evidence Session with Ulster Farmers’ Union.

The representatives joined the meeting at 10.15am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Graham Furey, Michael Harnett and David McIlrea, representatives from the Ulster Farmers’ Union. A question and answer session followed

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation.

PJ Bradley joined the meeting at 11.15am

The representatives left the meeting at 11.15am.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 11.15am.

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 11.20am.

2. Evidence Session with the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

The officials joined the meeting at 11.20am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Dr John Speers, Joyce Rutherford and Martin McKendry, officials from the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. A question and answer session followed

The Chairperson thanked the officials for their presentation.

The officials left the meeting at 12.30pm.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 12.30pm.

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 1.40pm.

3. Evidence Session with Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulator

The representatives joined the meeting at 1.40pm.

George Savage joined the meeting at 1.46pm.

The Committee took oral evidence from Iain Osborne and Sarah Brady, representatives from Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulator. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation.

The representatives left the meeting at 2.30pm.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 2.30pm.

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 2.50pm.

4. Evidence Session with Mr Ian Duff.

Ian Duff joined the meeting at 2:50pm.

The Committee took oral evidence from Mr Ian Duff. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked Mr Duff for his presentation.

Ian Duff left the meeting at 3.35pm.

5. Date, time and place of next meeting.

The next meeting will be held on Thursday 1st May in Room 144.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 3.37pm.

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Thursday, 1 May 2008

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present:

Dr William McCrea MP (Chairperson)

Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Thomas Burns

Trevor Clarke

Willie Clarke

William Irwin

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Lindsay Dundas (Clerical Officer)

Jim Kitchen (Special Advisor)

The Chairperson opened the public meeting at 10.00am.

1. Evidence Session with Action Renewables.

The representatives joined the meeting at 10.05am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Dr Andy McCrea, Terry Waugh and Jonathan Buick, representatives from Action Renewables. A question and answer session followed.

Tom Elliott joined the meeting at 10.10am.

William Irwin joined the meeting at 10.16am.

Thomas Burns joined the meeting at 10.19am.

Thomas Burns left the meeting at 10.53am.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation.

The representatives left the meeting at 11.18am.

2. Evidence Session with the Northern Ireland Environment Link

The officials joined the meeting at 11.19am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Professor Sue Christie, Pauline Mackey and Dr Peter Christie, representatives from Northern Ireland Environment Link. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked the officials for their presentation.

The officials left the meeting at 12.15pm.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 12.15pm.

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 1.39pm.

3. Evidence Session with World Wildlife Fund for Northern Ireland.

The representatives joined the meeting at 1.40pm.

The Committee took oral evidence from Malachy Campbell and Dr Alex McGarel, representatives from WWF Northern Ireland. A question and answer session followed.

Thomas Burns joined the meeting at 1.45pm.

P J Bradley left the meeting at 1.52pm.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation.

The representatives left the meeting at 2.21pm.

The Chairperson suspended the meeting at 2.21pm.

The Chairperson reconvened the meeting at 2.37pm.

4. Evidence Session with Mr Ian Duff.

The representatives joined the meeting at 2.37pm.

Tom Elliott joined the meeting at 2.42pm.

The Committee took oral evidence from John Hardy, Ruth McGuigan and Paula Keelagher, representatives from Sustainable Energy Association. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation.

The representatives left the meeting at 3.38pm.

5. Date, time and place of next meeting.

The next meeting will be held on Thursday 22 May in AFBI, Hillsborough.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 3.38pm.

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Thursday, 22 May 2008

Agri-Food And Biosciences Institute, Large Park, Hillsborough, Co Down

Present:

Dr William McCrea MP (Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Thomas Burns

Willie Clarke

William Irwin

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Jonathan Young (Clerical Officer)

Jim Kitchen (Special Advisor)

The Chairperson opened the public meeting at 10.04am.

1. Correspondence Issued

The Chair briefed the Committee on Correspondence issued regarding the Inquiry since the last inquiry meeting which was held on the 1 May 2008.

2. Correspondence Received.

The Chair briefed the Committee on Correspondence received regarding the Inquiry since the last inquiry meeting which was held on the 1 May 2008.

3. Committee Business – SR The Financial Assistance for Young Farmers Scheme

(Amendment) Order (NI) 2008

Question put and agreed.

That the Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development has considered the Financial Assistance for Young Farmers Scheme (Amendment) Order (Northern Ireland) 2008 and, subject to the Examiner of Statutory Rules report has no objection to the rule.

4. Evidence Session with The Carbon Trust.

The representative joined the meeting at 10.07am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Geoff Smyth, a representative from The Carbon Trust. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked the representative for his presentation.

The representative left the meeting at 10.52am.

5. Evidence Session with the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment.

The officials joined the meeting at 10.52am.

The Committee took oral evidence from Barbara Swann, David Sterling and Olivia Martin, representatives from the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment. A question and answer session followed.

The Chairperson thanked the officials for their presentation.

The officials left the meeting at 12.02pm.

6. Evidence Session with Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute.

The representatives joined the meeting at 2.33pm.

The Committee took oral evidence from Dr Lindsay Easson, Dr Alistair McCracken and Dr Peter Frost, representatives from Agri- Food and Biosciences Institute. A question and answer session followed.

William Irwin left the meeting at 3.09pm.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for their presentation and hosting the evidence session for the Committee’s Inquiry.

The representatives left the meeting at 3.20pm.

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Tuesday 24 June 2008

Room 152, Parliament Builidings.

Present:

Dr William McCrea (Chairperson)

P J Bradley

Allan Bresland

Thomas Burns

Trevor Clarke

Willie Clarke

Pat Doherty

William Irwin

George Savage

In attendance:

Paul Carlisle (Clerk to the Committee)

Emma Patton (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mary Hawthorne (Clerical Supervisor)

Jonathan Young (Clerical Officer)

Apologies:

Tom Elliott (Deputy Chairperson)

The meeting opened at 1.39pm in Closed Session.

1. Apologies

As above.

2. Committee Inquiry

Special Advisor, Mr Jim Kitchen presented to Committee the recommendations of the Inquiry. The Committee deliberated the draft report.

The Committee read and agreed the Membership and Terms of Reference.

The Committee read and agreed paragraphs 2-22

The meeting was adjourned at 5.05pm

[Extract]

Dr William McCrea

Chairperson, Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

24 April 2008

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Dr William McCrea (Chairperson)

Mr P J Bradley

Mr Allan Bresland

Mr Trevor Clarke

Mr Willie Clarke

Mr William Irwin

Mr George Savage

Witnesses:

Mr Martin McKendry |

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development |

1. The Chairperson: I welcome the next set of witnesses, who are from the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. I thank you for joining us this morning.

2. The Department’s ‘Renewable Energy Action Plan’ was launched on 29 January 2007. The Committee is interested in exploring what has happened since then. In making your presentation, I ask you to bear in mind the terms of reference of our inquiry into renewable energy and alternative land use.

3. Thank you for the response that you forwarded to the Committee. Please make your presentation, and we will have a question-and-answer session afterwards.

4. Dr John Speers (The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development): I thank the Committee for its invitation to attend the inquiry. My colleagues are Joyce Rutherford, who is head of the Department’s recently created renewable energy policy unit, and Martin McKendry, who is responsible for the renewable programme within CAFRE. We aim to address the inquiry’s aims and terms of reference in our opening statement.

5. DARD acknowledges that the development of renewable energy may open up opportunities to the agricultural community from the production and utilisation perspectives. Specifically, farmers could contribute to the production of energy in Northern Ireland, and the rural community could benefit from localised energy distribution.

6. DARD policy in that area sits within the sustainable-development goal of its strategic plan, the key objective being to encourage the increased exploitation of renewable energy opportunities. We are driving various actions to progress that objective. We are delivering the action plan, which was developed in consultation with stakeholders. We support a dedicated research and technology programme, which will provide an important evidence base for future policy in that area. We are exploiting opportunities to support renewable energy development through the Northern Ireland Rural Development Programme, and we are collaborating with the lead Department on energy issues, DETI, and others to ensure that opportunities for the agriculture sector are included in any wider public policies under consideration in that area.

7. We are conscious that the term “renewable energy” covers many areas. I will take a few minutes to focus on the Department’s approach to those areas.

8. Wind-generated energy is the most prevalent form of renewable energy available in Northern Ireland. Existing technology, in the form of wind turbines, offers a wide range of power ratings, from a few watts to several megawatts. We recognise that farmers can benefit from wind energy generation in a number of ways; specifically, by engaging with energy providers to assist the establishment of large-scale energy generation in the countryside. We can give those providers access to the land, for which the farmer receives an additional revenue stream. From that, there are a decreasing range of scales, down to wind-generated energy for single households or single businesses. To assist with the overall assessment of the current economic potential and the agrienvironmental impact, the Department has erected demonstration wind turbines at the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) campuses at Loughry and Greenmount.

9. I will now turn to biomass production. Short-rotation coppice (SRC) willow is grown specifically as an energy crop in Northern Ireland, mainly to generate heat. The product, in the form of willow chips, is used primarily as a fuel to generate heat in biomass boilers. Studies indicate that the economics of growing SRC willow as a fuel-only crop are marginal. We are aware that, bearing in mind recent energy prices, the economics of SRC willow are looking more attractive for heat production. We are also aware that the additional use of SRC willow for biofiltration has the potential to add value to the product, and, in turn will have a beneficial impact on the economic sustainability of the technology.

10. The constraints around the production of SRC willow in Northern Ireland are focused mainly on the availability of a local end-user, the cost of transport, and the distances travelled, bearing in mind the bulk and low value of willow chips. DARD provides some grant support, which is targeted at the establishment of wood-based SRC crop businesses and farm businesses through the SRC programme and the regional development programme. Linked to that support, under the programme to build sustainable prosperity, the energy from biomass infrastructure development scheme has allocated some £640,000 to 16 projects for the harvesting, drying and storage of SRC willow. CAFRE will continue to provide information by way of technology and knowledge transfer in this area, to assist landowners and farmers in making informed and rational choices about how to manage SRC businesses. DARD-funded work also continues at the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) on the commercial development of SRC willow.

11. The Department is working with AFBI to assess the economic potential and agrienvironmental impact of growing miscanthus, which is also a biomass crop, and a small number of other grasses, which might have the potential to contribute as energy-producing feed stock.

12. Biomass from forestry and sawmill residues are also being examined. Our estimates indicate that publicly-owned forests in Northern Ireland have the potential to generate around 42,000 tons of forest residues a year. For several reasons, however, it is not possible to collect all of that. We recognise that scope exists to promote forestry residues as a renewable energy source. DARD’s Forest Service is working with AFBI and scientists to investigate the commercial viability and economic potential of the recovery and utilisation of forest brash for biomass heating systems. Sawmill residues also provide some potential as a renewable energy source. Indeed, there have been some changes in the market forces around wood-fuel businesses. I have seen sawmill residues being made available for wood-fuel services.

13. There is potential, under the rural development programme’s agricultural and forestry processing and marketing grants scheme, to provide support to forestry-related micro-enterprises for capital expenditure on buildings and new equipment aimed at improving the application of technology in the forestry sector. That support must be made available for renewable energy technologies.

14. Another subject is energy crops for liquid-biofuel production. Bearing in mind that Northern Ireland has one million hectares of land — two thirds of which is less favoured area (LFA) land and only 3% to 5% of which is used for cereal production — oilseed rape is potentially a primary crop for biodiesel production. There are no particular climatic constraints to growing oilseed rape in Northern Ireland, and yields close to those achieved in GB have been recorded. Although there is potential for increased oilseed rape production in Northern Ireland, there are some significant restraints. The crop has a limited place in arable rotation, and, therefore, large-scale biodiesel production in Northern Ireland is unlikely.

15. Another liquid biofuel is the fossil-fuel, petrol substitution bioethanol, which is produced from wheat or sugar beet. In Northern Ireland, wheat is grown in a relatively small area — almost 9,000 hectares, from the June 2007 census — and no sugar beet is grown at all here.

16. Another relevant fact is that Northern Ireland is a grain-deficient region and must import large quantities of grain as feedstuffs for the livestock sector. Therefore, large-scale bioethanol manufacturing in the region is unlikely.

17. I shall now look at conversion technologies. The Department is examining the potential roles that anaerobic digestion and heat generation might play. The anaerobic digestion of organic waste is a proven, well-tried and tested technology that can be successfully used to produce biogas for combined heat and power. Anaerobic-digestion plant can be designed as small on-farm units to deal with slurry, or as larger units to deal with slurry from several farms. Such plant can also be used for co-digestion with other organic waste.

18. Recent developments using supplements and green crops — such as maize grass or whole-crop silage — as a feedstock in anaerobic-digestion plant can significantly improve the efficiency of biogas production.

19. The total housed, livestock-manure resource here is just less than 10 million tonnes, and, in theory, if all that were used for anaerobic digestion, it could fuel approximately 90 one-thousand-ton-a-year anaerobic-digestion plants with an energy output of 73 MW of electricity and 60MW of heat. However, that potential is unlikely to be fully realised. Obviously, there are alternative uses for manure as a nutrient source — such as on the land — and the location of farms in relation to supplying the grid is a further constraint.

20. In that context, we are exploring the potential for an energy-from-agrifood-waste challenge fund, which could be match-funded through the European Union’s structural fund, and we are proactively progressing the legal basis on which the Department might introduce such a scheme and any state-aid issues that might be relevant to it. We hope to shortly be in a better position to advise the Committee in more detail about that scheme.

21. Biomass heating systems and potential air-source and ground-source heating pumps are being trialled at CAFRE and AFBI, and Martin McKendry will talk about the technology associated with that.

22. Commenting specifically on the terms of reference, concerning the policy framework for the development of renewable energy in Northern Ireland; there are a range of EU-level policy initiatives that are driving the renewable-energy agenda.

23. The Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment holds the energy portfolio for Northern Ireland and takes the lead on all energy-related matters. Within that, DARD’s renewable energy action plan has been a catalyst in providing a focus for the Department’s efforts to identify the activities that support the development of renewable energy in the agrifood sector. The majority of those actions has been implemented, but some are still works in progress.

24. One of the actions to progress the implementation of activities in the renewable energy action plan, and to continue with DARD’s policy development of renewable energy in the agrifood sector, was to establish a unit within the central policy group, which Ms Rutherford heads up. The team was established some six months ago and plays a central role in developing the Department’s future renewable energy policy.

25. Mr McKendry will now say a few words about some current and future renewable energy technologies.

26. Mr Martin McKendry (The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development): It is fair to say that DARD recognises the growing interest in renewables in the agricultural and rural communities. That interest stems from increasing energy costs, increased awareness of climate change and EU targets. Those communities recognise that they have the resources, that is, the land, to provide solutions to some of those problems.

27. The renewable energy technologies that are available include wind, solar, photovoltaics, tidal, wave, and ground- and air-source heat pumps. Some of those technologies will have an impact on the agricultural and rural community, but some will not. However, we wish to concentrate on bioenergy, which includes biogas, biomass and biofuel.

28. There are three opportunities for farm businesses. Before we even address the issue of renewables, we must first address the main issue, which is to reduce energy consumption. There are also opportunities for farm businesses to displace fossil fuel energy in favour of producing their own heat, electricity or even biodiesel.

29. The second option is for farm businesses to produce feedstock from the land or from waste, eg, slurry, and sell or market that commodity.

30. The third option is to work together to market energy and the business opportunities that arise from that — the idea being to move up the supply chain.

31. The environment and renewable energy fund has concentrated on demonstrating existing technologies for farm businesses through AFBI, from a research point of view, and through CAFRE, from a knowledge and technology transfer point of view. We have been involved in a range of technologies, including biomass and wind turbines. There is also a sustainable energy unit, which uses combined renewable technologies such as biomass and solar. At Loughry campus, an air-source heat pump has been installed and land has been allocated so that the potential for non-food crops can be investigated. Non-food crops include biomass and other alternative market opportunities.

32. Our means of disseminating that information to the industry largely came about through a renewable energy open day in August 2007, which we ran in conjunction with the industry and with stakeholder partners. Information was also provided through our training in knowledge and technology transfer.

33. DARD has previous experience from the food side and from the production side of pulling farmers together to meet market requirements. Those transferable skills can also be used for the renewable side in the future.

34. Dr Speers: One of the Committee’s terms of reference relates to the range of support that is available for renewables initiatives, and Joyce Rutherford will talk about that.

35. Ms Joyce Rutherford (Department of Agriculture and Rural Development): Thank you for giving me the opportunity to present evidence to the Committee.

36. John and Martin’s presentations touched on some of the support that is available, but I will summarise it for the Committee. EU aid is available for the establishment of energy crops through a very modest scheme that was set up in 2004 to incentivise the growing of feed stock for bioenergy purposes across the EU.

37. In Northern Ireland, the main crop grown under that scheme is SRC willow, although a very small amount of oilseed rape is grown as well. It is likely that, because the ceiling has been reached on available funding across the EU, and because feed stock has been established, that modest scheme will finish after the next common agricultural policy health check. The Department is not aware of the details of that, but it is a matter of watching this space.

38. Support is available for renewable energy technologies under axis 1 and/or axis 3 of the Northern Ireland rural development programme 2007-13. In particular, under axis 1, agriculture and forestry processing and marketing grants may be able to support renewable-energy technologies. Under axis 3, the farm diversification scheme and the business creation and development programme will support renewable energy projects.

39. As John already highlighted, we are exploring the potential of a fund for the production of energy from agrifood waste, and we hope to be able to come to the Committee later this year with the outcome of that exploration.

40. With regard to the European renewable energy fund, the Committee will be aware that DARD has secured a total fund of £4·2 million. That fund is now closed. Basically, our aim was to secure some funding for research and demonstration purposes in order to prove the concept of some of the technologies that are available and to ensure that they are suitable for the Northern Ireland agenda and environment.

41. To carry on from that, although the EREF is closed, we were able to secure some funding through the Chancellor’s innovation fund to continue with our programme of technology transfer at CAFRE and the renewables research programme at AFBI. Therefore, although the EREF is closed, work is continuing through other funding streams to ensure that renewables are kept firmly on the agenda.

42. I shall now pass the Committee back to John. Thank you.

43. Dr Speers: To conclude, in looking at the terms of reference in relation to the potential role of farm and rural businesses and the ways in which DARD could implement a strategy for renewable energy, we recognise that we now have an action plan. As indicated in that action plan, it will be subject to review this year. That review will set out the strategic direction over the next three years, taking account the work of this Committee and the work of DETI and others as well as the wider energy policy that is developing in Northern Ireland.

44. The Chairperson: Thank you very much John, Joyce and Martin, for your presentation.

45. The Committee has heard evidence from the Ulster Farmers’ Union, and there will be several contributors to its inquiry. People from different Departments will be listening to different parts of the evidence. I and other members of the Committee appreciate all participants’ evidence, but I would be interested to receive representations that comment on, or even challenge, some of the presentations being given, so that the Committee can get an overall view. Each participant gives a presentation, and the Committee interviews him or her on the basis of it.

46. However, it is difficult to have interaction between different participants because the discussion will be wide-ranging. Therefore, I would like to have comments, and even challenges, if that is necessary. If that it not necessary, then, to be honest, we are not looking for a challenge for its own sake.

47. To return to the heart of the matter; namely, DARD’s renewable energy action plan, which has been operating for 15 months; please outline the plan’s achievements during that time?

48. Dr Speers: I shall ask Joyce to provide some of the detail. However, to preface some of her comments, we recognise that this was a new area of work for DARD. We have been investing in increasing our knowledge of the technology and our expertise in this area and in working with various stakeholders and centres to enhance our knowledge.

49. A key development has been to establish the policy unit in DARD to bring together, in a co-ordinated way, efforts across the Department. To that end, part of the unit’s remit is to establish a group of interested parties across the Department. That includes the research at AFBI, the technology work at CAFRE, the support available through our rural development colleagues, and the various interests on the forestry side. Over the past six months the Department has considerably strengthened its focus on renewable energy. The Department is also very aware of the requirement to undertake a substantial review of its action plan.

50. Ms Rutherford: The plan has 35 recommendations for action, of which 27 are under way or have been completed. Some, such as the review of the action plan, will be tackled shortly. Moreover, many of the actions were addressed under the EREF work, such as the technology transfer programme and the installation of demonstration technologies. Work is definitely under way. We have just completed our baseline, and we hope to give that to an industry-led stakeholder group soon, which will re-evaluate the action plan and suggest a longer-term strategy for the next three to five years.

51. The Chairperson: On which of the 35 recommendations has progress been made, and where is the evidence? We have to see, and be able to measure, what had been achieved. A review of the action plan was promised for this month. Is that review continuing? Your comments gave the impression that the review is about to commence.

52. Ms Rutherford: You have asked me a couple of questions, so please let me answer them. Take, for example, recommendation 1 in the action plan, which seeks to further increase the awareness of renewable energy technologies among the wider rural community. One activity that has already taken place was the CAFRE open day. Members may have had the opportunity to attend. There were 500 attendees. The Department has actively raised awareness of renewable-energy technologies among 500 people.

53. The Chairperson: It is not a one-day wonder, Joyce.

54. Ms Rutherford: I understand that. However, it represents an incremental step change for the agricultural community.

55. The Chairperson: There are tens of thousands of farmers. I applaud the occasion that you mentioned. I found it helpful and informative. How can that information reach other farmers?

56. Ms Rutherford: Martin can provide further details on that.

57. Mr McKendry: With regard to the 15-month action plan, the Department has initiated seven technology-transfer projects in CAFRE. We have delivered training, including the open day, to just over 1,500 farmers. That training has been organised specifically by CAFRE. Therefore, in addition to presentations that the Department has been asked to give at other meetings, it has specifically provided training to 1,500 farmers.

58. Those projects have delivered. Fifteen per cent of CAFRE’s heat and 1% of its electricity are now derived from renewable sources. With regard to your question on how awareness is being generated among farmers on the ground, the Department is in the process of spreading it further through training programmes. Last month, 103 dairy farmers participated at five events throughout Northern Ireland on practical ways to reduce their energy consumption. Another 80 attended the first of four SRC workshops. That work brings renewable energy into the training sphere and away from the awareness phase. During the next couple of years, the Department’s work will be to provide much more training to individuals and small groups.

59. Ms Rutherford: Papers are being prepared concerning the formulation of the stakeholder forum that will be set up to review the plan. We hope to make progress on that structure quickly, within the next eight weeks. The time frame has been scoped. We hope that the review will be complete around the end of the year. There is a timing issue because several studies are being carried out. The Department is keen to find out the outcome of this inquiry as well so that all of those considerations can be taken by the stakeholder group that will review the action plan.

60. The Chairperson: It would be difficult to respond to all 35 recommendations. Therefore, please send the Committee the Department’s position and the progress that has been made on each of them. The Committee wants to know about those that the Department cannot or is unable to progress. We do not want to see a flowery picture if there are weeds.

61. Dr Speers: I was going to offer to provide a progress report on the action plan. As you have indicated, the action plan was drawn up some time ago when the renewable-energy sector was in its infancy. Many of the recommendations may have been speculative in nature and have not been progressed for various reasons, including economic ones. The Department will certainly provide a detailed progress report on the action plan.

62. Mr W Clarke: What steps has the Department taken to get other Government Departments to buy into the plan?

63. Ms Rutherford: The Department has representation, through DETI, on a group in which Departments work together on a study to assess the potential market opportunities for renewable energy in Northern Ireland. Several Departments feed into that study. Therefore, there is a degree of cross-departmental co-ordination on the matter.

64. Mr W Clarke: There is co-operation but no action. Officials say that renewable energy has nothing to do with their Department but rather that it is the responsibility of someone else’s — it is like a game of tennis with the issue bouncing back and forth. Instead, officials should take the initiative by forming an action plan and demanding buy-in from all Departments.

65. If the farming community is being asked to grow a raw product, the market for that product must be provided. The Social Development Minister, Margaret Ritchie, and her Department must be asked to ensure that there biomass facilities are used in every new housing estate, and the Environment Minster, Arlene Foster, and her Department must be asked to ensure that biomass facilities are used in every Government building. That seems straightforward to me and that is what officials should be doing.

66. Dr Speers: I share your ambition that the market will be a driver for sustainable business, based on renewable energy, to which many Departments must contribute. That degree of co-ordination is not yet in place.

67. The Chairperson: It is easy to look at what others are doing. As the Committee heard in the first presentation today, promoting sustainable energy affects all Departments, making it vitally important that there is a co-ordinating body, whether it is OFMDFM, to bring them together. However, what is DARD’s target for renewables? Your silence suggests that such targets do not exist.

68. Mr McKendry: The CAFRE estate, which is part of DARD, has clear targets on renewable energy, which I referred to earlier, including a 10% reduction in energy consumption, 15% efficiency saving from renewable heat and 1% from renewable electricity.

69. Mr Chairperson: What is the Department’s PSA target for renewable energy?

70. Dr Speers: I do not have that specific information to hand.

71. The Chairperson: Will the Department provide that information?

72. Dr Speers: Certainly.

73. The Chairperson: I am concerned that on the one hand the Committee is being told that there needs to be a driver to use biofuel because of the economic challenges — profitability, sustainability — that farmers face today, whereas, on the other hand the challenge is rising fuel costs. What steps are the Department taking to: first, help farmers to utilise renewable-energy technology on their land and; secondly, to assure them that their businesses are going to be more profitable than at present? There has to be something to drive the process forward.

74. Dr Speers: There are a number of options available within renewable energy, of which many were outlined in our opening remarks.

75. The Chairperson: Those seem to relate to a long-term approach. How far does that vision extend?

76. Dr Speers: The Department’s approach is based on the view that those technologies — their efficiencies, contributions and sustainability — need to be proven in the Northern Ireland context. For many of those, that has yet to be done. As you indicated, Chairperson, cost infrastructure has changed over recent times. Therefore, before the Department makes commitments and recommendations it needs to ensure that there will be a sustainable market for the outputs.

77. We are all aware of the vulnerability of the food-production market — price reductions and fluctuations — which depends on factors outside our control. We do not want to move into commodity energy production, which would potentially suffer from the same fluctuation in prices.

78. We need to somehow determine where the niche is for Northern Ireland and where the value added is. Given the scale of our operation, we should not be a commodity player.

79. The Chairperson: You say that we have to somehow to arrive at that point, but who is determining where the niche is, and what timescale are we talking about? Is this matter on the long finger? It seems that immediate challenges — indeed, any challenges — are always put on the long finger.

80. Dr Speers: As Martin said, a range of trials are currently under way, and they are very focused and commercially oriented. They are the subject of both technological and economic analysis. The findings of those trials are being rolled out as we speak. They are real live projects that demonstrate the viability of renewable energy technology on farms now.

81. The Chairperson: You said that you are going to present some of that evidence.

82. Mr W Clarke: I want to pick up on a point that you made, Chairperson. It is fair enough to have trials and research and so on, but it seems that that is all that comes from the Department. All we hear is that the Department is looking at this or that, or that it is running a pilot scheme and so forth. All those technologies are proven throughout Europe, and we are playing second fiddle to the rest of Europe. What will happen? We will be passed by — we are that far behind.

83. I do not blame the Department; this problem is a hangover from direct rule. However, a sense of urgency is required. At the minute, as the Chairperson said, people are under immense pressure and are facing fuel poverty, and the Assembly, as an elected body, can do nothing about that. However, it can ensure that renewables are in place in the North of Ireland and Ireland. There should be less testing and more getting on with it.

84. What funding requests for renewables did the Department make to DFP in the last monitoring round?

85. Ms Rutherford: In the last monitoring round, a total of £2·55 million was secured from DFP for the next three years under the Chancellor’s innovation fund.

86. Mr W Clarke: That is peanuts. The Department should say to DFP that it needs £30 million.

87. The Chairperson: The Department certainly should not say that if does not have any programmes prepared. There is no use in making demands for money if there is no programme on which to spend it. If a Department is asking DFP or anyone else for funding, it must have a programme to put on the table, and it must be costed. One cannot simply demand £30 million and have no reason for doing so.

88. I am wondering why the Department has not presented DFP with programmes. Why has it not said, “This is exactly where our plans are, and we need finance to put them into operation.” To the best of my knowledge, £10 million was available in the Programme for Government. How much funding has been pulled down from that? How much of the money available from Europe has been secured?

89. Mr W Clarke: That is precisely what I am saying. I could draw up plans for the bids. The Department will never get a better opportunity to act than now. The community is in crisis because of fuel prices, and there will never be a better time for the Department to approach the Executive with a plan to resolve the issues involved. It should be telling them that it can do something about this issue, rather than saying that it cannot do much because of the global markets. This is an opportunity for the Department to take the lead and say that it wants proper measures to be implemented. There must be a cross-cutting approach across all Departments.

90. Mr T Clarke: My question follows on from the member’s question. He asked how much the Department received in the last monitoring round. The Department said that it received £2·55 million, and he said that that was peanuts. How much did the Department bid for?

91. Ms Rutherford: A number of bids were made under various umbrella headings. A bid was placed for money from the innovation fund, which I mentioned earlier, and a bid was made for the potential energy from the agrifood waste challenge fund.

92. Mr W Clarke: You said that the Department received £2·55 million, but how much did it bid for?

93. Ms Rutherford: That was a specific bid, and that bid was met.

94. Mr T Clarke: So the Department asked for peanuts, and it got peanuts. You did not make a substantial bid —

95. The Chairperson: With the greatest respect, we are only talking about peanuts if the bid that is submitted can be sustained. If the bid is not sustainable and cannot be scrutinised in depth, having been presented by the Department, there is no use bidding for money that is not going anywhere. The DARD renewable energy action plan has been in place for 15 months. It is easy to say that direct rule was in operation for part of that time, but we are no longer subject to direct rule. We are a year on from devolution; we cannot hide behind anyone else. We are talking about an action plan. The word “action” is to the forefront here. I am trying to find out exactly what action has been taken, because it is only on action that a bid can be made.

96. Dr Speers: There are a couple of fundamental points to be made. The Chairperson has underlined the importance of having a robust business case in advance of making a bid. One of the most important issues is market demand, which at the moment is unclear. There is no definitive position with regard to market demand. Two research projects, led by DETI, are under way to examine the market for renewable energy in Northern Ireland. That work will provide the information and evidence base against which bids can be made. Coupled with that, we must ensure that we invest in the right technology areas. We have already mentioned how renewable energy embraces a wide range of technology areas from different renewable sources. We must ensure that investment in Northern Ireland is appropriate for us. That is why the trials, the research, the development work and the commercialisation is ongoing at AFBI and CAFRE, so that we have an evidence base on which to base further proposals for —

97. Mr T Clarke: John, with the greatest respect; you said that a wide range of technologies is being developed. Why can we not pick one of those technologies after 15 months? Why are we not at the stage where one of those technologies is up and running? Why are we still talking about what is out there? Willow is not new. I do not know a lot about the technologies, but I have heard enough about them. In your previous presentation you made the point that willow technology is not new in other countries either. Why are we not looking at what everyone else is doing and copying them, as opposed to being left behind, as was said earlier?

98. Mr McKendry: We are at the demonstration phase at the moment, and people are adopting biomass burners.

99. Mr T Clarke: What are you doing to assist those developments?

100. Mr McKendry: Do you mean from the financial perspective, or the knowledge perspective?

101. Mr T Clarke: I mean from the financial perspective.

102. Ms Rutherford: Support is available from the rural development programme and can be applied for. Those have been widely publicised to the agricultural community. Applicants can work with rural connect Advisors to point them in the right direction.

103. Mr T Clarke: What are those?

104. Ms Rutherford: Rural connect Advisors are agricultural Advisors —

105. Mr T Clarke: What support has been widely advertised that we should be aware of?

106. Ms Rutherford: There are measures available under the agricultural processing and marketing grants scheme, particularly in support of forestry renewable technologies. Support is also available for the establishment of SRC willow technology from the woodland grants scheme. Axis 1 funding facilitates groups of farmers who come together to work on renewable energy projects. Support is also available for farm diversification. There is a wide range of measures, but we have to build confidence in the agricultural industry that those technologies can work commercially. DARD is focusing a great deal of effort on raising awareness and training.

107. Dr Speers: If it would be helpful, we can provide a table of the various financial assistances available from DARD for renewable energy technologies.

108. The Chairperson: What is the structure of the grants? Who can apply for the money? There are certain moneys set aside for rural areas. It is questionable how those moneys will be deliverable.

109. Dr Speers: There is scope to provide financial assistance for microbusinesses under the processing and marketing grant scheme and the forestry scheme. It might be helpful to the Committee to have a table of the various financial support measures in place or planned for.

110. The Chairperson: The phrase “planned for” can be a very elastic one. If schemes are opening, then I would like to know exactly when they are opening and how people can apply for grants.

111. Time is passing; and there a number of questions to be asked.

112. Mr Irwin: Given your experience to date, which of the available renewable energy systems offers the greatest potential benefit to rural communities while contributing to the attainment of the Government’s renewable energy targets?

113. Mr McKendry: There are a couple of issues in that question. The first is biomass, and centralised biomass systems. In Northern Europe, there are centralised plants producing hot water and delivering it to houses. Members of the UFU mentioned that earlier. The technology is sound and well proven, and the idea that the farming community would be moving up the supply chain, and would be delivering heat rather than wood chip, is more beneficial.

114. The second issue is anaerobic digestion, which is something that the Department has studied in Europe. We have looked at the economics and feasibility of anaerobic digestion, not only from the perspective of waste usage, the economics of which are marginal, but also from the perspective of production and green-crops, where the economics are much stronger. Those are the two main renewable energy systems in Europe that are well proven and well used and would provide local rural solutions in Northern Ireland.

115. Mr W Clarke: John — you talked about market demand. DARD can help create market demand — it is within the Department’s remit to do so. All schools could have biomass heating systems, and the same could apply to hospitals, museums and social housing. DARD should be talking to the other Departments and saying to them that this is what is being proposed will happen three years from now. Let us look at this matter in a cohesive fashion, and roll it out. This is not rocket science, and I am not shooting the messenger.

116. It is frustrating because this is something that is within the Department’s remit. The forestry industry could be included as well, because it is always being said that there are not enough trees in Ireland — this is a win-win situation. The trees grown do not have to be willow trees — any trees could be used for this purpose. It has been said that there is an investigation into forestry residue and into the recovery of wood residue. What is there to investigate? If there are any fallen trees; take them, chip them, and put them into a biomass burner.

117. Dr Speers: I agree that the concept of creating market demand and discussing the matter with other Departments is something that needs to be addressed pro-actively.

118. We need to have a better understanding of the scale and production of the field stock — and its potential constraints — before we encourage the introduction of a different heating or energy system to schools or hospitals, because the products might be vulnerable to a lack of consistent supply in the future.

119. Mr W Clarke: John — you could get the farmers together through the Ulster Farmers’ Union. You could have the raw materials ready in three years’ time. It is Civil Service jargon to say: “We are doing this, or we are doing something else”. You have admitted that the benefits of the technology have been proven throughout the world. Let us implement it here. If, as a result of this inquiry, we achieve that, then it will have been a success.

120. Dr Speers: I do not disagree. My only note of caution concerns whether a sustainable supply of the field stock required will be available.

121. Mr W Clarke: Grow the trees.

122. Dr Speers: Farmers are businessmen, and they will utilise their land in whatever way necessary to maximise their returns. It would be great if that could be achieved by growing fuel crops, but market dynamics can change. For instance, the cereal market is good at the moment. Market changes have the potential to disrupt supply and the continuity of supply of field stock.