Session 2009/2010

First Report

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Report on the Inquiry

into Public Procurement

in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee relating to

the Report, Written Submissions, Memoranda and the Minutes of Evidence

Ordered by The Committee for Finance and Personnel to be printed 10 February 2010

Report: NIA 19/08/09R

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Finance and Personnel is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department of Finance and Personnel and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has the power to;

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Finance and Personnel.

Membership

The Committee has eleven members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee since its establishment on 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Ms Jennifer McCann (Chairperson)

Mr Peter Weir (Deputy Chairperson)

Dr Stephen Farry Mr Fra McCann

Mr Simon Hamilton Mr David McNarry*

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin Mr Declan O’Loan

Mr Adrian McQuillan Ms Dawn Purvis

Mr Ian Paisley Jnr**

*Mr David McNarry replaced Mr Roy Beggs on 29 September 2008

**Mr Ian Paisley Jnr replaced Mr Mervyn Storey on 30 June 2008

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations and acronyms used in the Report

Executive Summary

Key Conclusions and Recommendations

Introduction

- Background

- Scope and Terms of Reference

- The Committee’s Approach

- Themes from the Evidence

Consideration of the Evidence

The Procurement Environment

- European Legal Framework for Public Procurement

- The Scope of Public Procurement Practice

- Public Procurement Principles

- Organisational structures for the development and implementation of Procurement Policy in Northern Ireland

- Northern Ireland Executive

- Procurement Board

- Central Procurement Directorate

- Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs)

- Procurement Practitioners’ Group

- Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland Procurement Task Group

- Social Economy Enterprise Procurement Group

- Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in Northern Ireland

- Social Economy Enterprises in Northern Ireland

- Number and Value of Awards across the Centres of Procurement Expertise

Improving Policy and Processes

- Framework Agreements and Contracts

- Opportunities to Bid

- Tendering and Delivering

Maximising Social Benefit

Building Capacity for Purchasers and Suppliers

Local Government Procurement

Collaborative Procurement and Efficiencies

Litigation and Lessons Learned

Public Procurement Governance Arrangements

List of Appendices

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3

Written Submissions

Appendix 4

Memoranda and Papers - Department of Finance and Personnel

Appendix 5

Memoranda and Papers - Others

Appendix 6

Research Papers

Appendix 7

Stakeholder Conference Report and Papers

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in the Report

BERR |

Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform |

|---|---|

BiTC |

Business in the Community |

BSO |

Regional Business Support Organisation (DHSSPS) (operational from April 2009) |

CAJ |

Committee on the Administration of Justice |

CBI |

Confederation of British Industry |

CIFNI |

Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland |

CIGNI |

Construction Industry Group for Northern Ireland |

CIPS |

Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply |

CoPE |

Centre of Procurement Expertise |

CPD |

Central Procurement Directorate |

CSR |

Comprehensive Spending Review |

DEL |

Department for Employment and Learning |

DETI |

Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment |

DFP |

Department of Finance and Personnel |

DHSSPS |

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety |

DoE |

Department of the Environment |

DTS |

Delivery Tracking System |

EC |

European Commission |

ECJ |

European Court of Justice |

ECNI |

Equality Commission for Northern Ireland |

EEN |

European Enterprise Network |

ELB |

Education and Library Board |

ESA |

Education and Skills Authority |

EU |

European Union |

FSB |

Federation of Small Businesses |

GB |

Great Britain |

GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

GVA |

Gross Value Added |

HCSA |

Health Care Supply Association |

HSC |

Health and Social Care |

ICAGNI |

Independent Consultant Adviser Group in Northern Ireland |

ICT |

Integrated Consultant Team/Information Communication Technology |

ICTU-NI |

Irish Congress of Trade Unions – Northern Ireland |

IDBR |

Inter-Departmental Business Register |

IoD |

Institute of Directors |

IREP |

Independent Review of Economic Policy |

ISNI |

Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland 2008 – 2018 |

IST |

Integrated Supply Teams |

ITI |

InterTradeIreland |

ITT |

Invitation to Tender |

KTPI |

Knowledge Transfer Partnership Initiative |

LGPG |

Local Government Procurement Group |

MEAT |

Most Economically Advantageous Tender |

MLA |

Member of the Legislative Assembly |

MOD |

Ministry of Defence |

MP |

Member of Parliament |

MSP |

Member of the Scottish Parliament |

NDPB |

Non Departmental Public Bodies |

NGO |

Non-Government Organisation |

NHS |

National Health Service |

NHSSC |

National Health Service Supply Chain |

NI |

Northern Ireland |

NIAO |

Northern Ireland Audit Office |

NICS |

Northern Ireland Civil Service |

NICVA |

Northern Ireland Council on Voluntary Action |

NIFHA |

Northern Ireland Federation of Housing Associations |

NIHE |

Northern Ireland Housing Executive |

NILGA |

Northern Ireland Local Government Association |

NIPS |

Northern Ireland Prison Service |

NIW |

Northern Ireland Water |

ODA |

Olympic Delivery Authority |

OFMDFM |

Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister |

OGC |

Office of Government Commerce |

OJEU |

Official Journal of the European Union |

PAC |

Public Accounts Committee |

PfG |

Programme for Government |

PPG |

Procurement Practitioners’ Group |

PPP |

Public Private Partnership |

PQQ |

Pre-Qualification Questionnaire |

PR |

Public Relations |

PSA |

Public Service Agreement |

PTG |

Procurement Task Group |

PwC |

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC |

QPANI |

Quarry Products Association Northern Ireland |

RICS |

Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors |

RoI |

Republic of Ireland |

RPA |

Review of Public Administration |

RSUA |

Royal Society of Ulster Architects |

SBS |

Small Business Service |

SCA |

Special Contract Arrangements |

SEE |

Social Economy Enterprises |

SEN |

Social Economy Network |

SI |

Statutory Instrument |

SIB |

Strategic Investment Board |

SLA |

Service Level Agreement |

SME |

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises |

SPAP |

Sustainable Procurement Action Plan |

SROI |

Social Return on Investment |

SRPP |

Socially Responsible Public Procurement |

UCIT |

Ulster Community Investment Trust |

UK |

United Kingdom |

VAT |

Value Added Tax |

VCO |

Voluntary and Community Organisation |

VCS |

Voluntary and Community Sector |

VfM |

Value for Money |

WIN |

Western Innovation Network |

USEL |

Ulster Supported Employment Ltd. |

Executive Summary

Public procurement is an important element of the economy in Northern Ireland, with central and local government spending upwards of £3 billion annually on the purchase of supplies, services and construction works. This level of expenditure offers real potential in terms of maximising the economic and social outcomes for the local community.

The strategic direction of public procurement policy in Northern Ireland is set by the Executive; with the Procurement Board, chaired by the Minister of Finance and Personnel, overseeing the development and implementation of this overarching policy, supported by the Central Procurement Directorate within the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Executive’s Programme for Government 2008-11,Building a Better Future, highlights the positive role that procurement has in furthering cross-cutting sustainable development and socio-economic objectives. The Executive has also placed an emphasis on “growing the private sector including small and medium enterprises" and on “developing the social economy". Whilst the predominance of smaller enterprises in the local economy is widely acknowledged, there is also now a growing awareness of the valuable role for social economy enterprises, in terms of operating a commercial business model for social, community or ethical purposes.

Moreover, it is internationally recognised that benefits can accrue for both the public sector and the economy as a whole, by increasing the involvement of small and medium enterprises in the government supply chain, including better value for money, business growth and innovation. Also, for social economy enterprises, access to a large and stable market provides a stronger basis from which they can deliver important social policy outcomes.

Mindful of these benefits and of the potential to use public procurement strategically, as a tool for supporting the longer-term economic and social well-being of Northern Ireland, the Committee for Finance and Personnel agreed, in November 2008, terms of reference for this Inquiry into Public Procurement Policy and Practice in Northern Ireland. Given the many facets of government purchasing, the Committee chose to focus on specific aspects of policy and practice, including the experience of small and medium enterprises and social economy enterprises in tendering for and delivering public contracts; and the ways in which the social and economic benefits of procurement can be maximised.

Following a call for evidence, the Committee received written submissions from a wide range of stakeholders and a number of these organisations subsequently provided oral evidence. Given the breadth of issues raised and the variety of interests, the Committee also hosted a Stakeholder Conference, which represented a new approach to gathering inquiry evidence. This event was highly interactive and included breakout sessions, inputs from procurement commentators from other jurisdictions, plenary discussions and digi-voting on priorities and recommendations. The Committee also received academic opinion on the output from the Conference, which further informed the evidence base for the Inquiry.

Arising from the Inquiry, the Committee has made a number of key findings and recommendations, which it considers will help to achieve priorities within the Programme for Government and will benefit the public sector, business and the third sector respectively.

Key Conclusions and Recommendations

The Procurement Environment

1. The Committee recognises the business opportunities presented to indigenous enterprises by the substantial expenditure on public procurement in the Northern Ireland, all-island, Great Britain and wider European Union markets. However, the Committee is also mindful that the Northern Ireland business economy overwhelmingly comprises smaller enterprises, many of which consider that the public procurement process requires more time, effort and cost than business would allow. As such, the Committee considers that it is incumbent upon the Executive and the Assembly both to create a public procurement environment that facilitates our smaller enterprises in realising their full potential and which maximises the economic and social impact from expenditure on procurement. (Paragraph 41)

2. The Committee believes that the implementation of the recommendations arising from this Inquiry will help to achieve key objectives of the Executive’s Programme for Government, not least the emphasis on “growing the private sector including small and medium enterprises" and “developing the social economy". As a prerequisite, however, the existing drivers for public procurement will need to be realigned in support of the Executive’s economic, social and environmental priorities. In particular, this will require a more balanced application of the twelve guiding principles governing the administration of public procurement in Northern Ireland, which, in turn, will help achieve “best value for money". (Paragraph 57)

3. The Committee recommends that the Procurement Board, in conjunction with the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment, considers refining the definition of small and medium sized enterprises in the Northern Ireland context, paying particular attention to those currently identified as small, or micro-businesses, when exploring ways of boosting access to procurement opportunities by local businesses. (Paragraph 71)

4. The Committee believes that a “win-win situation" will arise from increasing the number of indigenous smaller enterprises competing in the public sector supply chain. For the public sector there is the potential for better value for money, better levels of service and more innovative business solutions. For the smaller enterprises there is the benefit of access to a large and stable market. The Committee also believes that increased participation by indigenous small enterprises in providing services, supplies and works to government in Northern Ireland could encourage their growth and participation in public procurement markets elsewhere, with the added benefits of boosting employment and of raising the level of productivity/Gross Value Added within Northern Ireland. (Paragraph 79)

5. In light of the potential benefits, the Committee calls on the Executive to develop a strategic policy for using public procurement, as far as is permitted under the legislation, as a tool for supporting the development of our smaller enterprises and for stimulating economic growth in the longer term. The Committee considers that the implementation of such a policy will require further culture change on the part of government purchasers, which sees a stronger focus on “growing the economy" and creativity in developing procurement solutions which are sensitive to the needs of the economy, whilst also ensuring legal compliance. (Paragraph 81)

6. The Committee calls on the Procurement Board to ensure that the necessary data capture and management information systems are put in place across all the Centres of Procurement Expertise to enable the impact of procurement policy on the small business and social economy sectors to be monitored effectively. The Committee further recommends that the criteria used in the accreditation of Centres of Procurement Expertise should take account of the robustness of the data systems in this regard. (Paragraph 92)

Improving Policy and Processes

7. Whilst accepting that the Central Procurement Directorate and the other Centres of Procurement Expertise must comply with both European Union and United Kingdom legislation, the Committee is of the view that the Procurement Board should reconsider the distribution of risk within the procurement process and bring forward a policy on risk sharing, which takes account of the barriers to smaller enterprises accessing the supply chain. (Paragraph 115)

8. The Committee recommends that large-scale framework agreements should not be used in future unless the Procurement Board can first establish a robust evidence base for following such practice in the Northern Ireland context. (Paragraph 116)

9. The Committee recommends that the Procurement Board gives careful consideration to a procurement policy that advocates breaking contracts into lots as the first recourse of any procurement tender. The intention of such action should not be to avoid the application of the appropriate public procurement regulations, but rather to make a conscious effort to reduce barriers to access for small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises. (Paragraph 123)

10. The Committee recommends that, when using framework agreements, the Central Procurement Directorate and the other Centres of Procurement Expertise develop frameworks reflecting various sizes of contracts and opportunities and, where appropriate, give consideration to regional contract variations to increase access to opportunities for smaller enterprises. (Paragraph 127)

11. The Committee recommends that the Procurement Board gives careful consideration to the full range of methods of procurement, including the use of alternatives to frameworks agreements and traditional contracts where appropriate. In particular members are keen to see a flexible approach taken to contract variance. (Paragraph 131)

12. The Committee recommends that the Procurement Board takes steps both to consolidate all Northern Ireland public sector procurement opportunities within the remit of thee-SourcingNI web portal, including local government tender notices, and to integrate tendering opportunities in Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. (Paragraph 148)

13. The Committee recommends that the provision of timely and accurate information on the e-SourcingNI portal and the Investment Strategy Northern Ireland Delivery Tracking System should be written into both the business plans of each Centre of Procurement Expertise and the personal performance agreements of the responsible officials. Moreover, Centres of Procurement Expertise should also be required to publish their annual procurement plans on the e-SourcingNI portal to assist small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises in forward planning. (Paragraph 151)

14. Notwithstanding the need for improved data collection by Centres of Procurement Expertise, the Committee believes that the Executive should keep under review the option of setting targets for increased participation by small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises in the public sector supply chain, for possible future use in the event that the other identified policy interventions do not have sufficient impact. (Paragraph 155)

15. The Committee recommends that the Central Procurement Directorate encourages local small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises to collaborate, where appropriate, by highlighting the benefits of such initiatives and by providing guidance on the legal and practical implications of joining consortia to facilitate joint tendering. In noting the ongoing work by the Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland on collaborative bids in relation to the construction sector, the Committee recommends that the Procurement Board considers the potential application of this model to also cover supplies and services and its extension to all Centres of Procurement Expertise. (Paragraph 160)

16. The Committee considers that purchasers should give more consideration to the overall supply chain when awarding contracts and calls on the Procurement Board to examine the scope for government to take greater control of sub-contract arrangements in public contracts, with a view to ensuring more open competition and added transparency. (Paragraph 167)

17. The Committee recommends that the Central Procurement Directorate and the other Centres of Procurement Expertise consider the scope both for greater use of up-front and interim payments, within the constraints of government accounting rules, and for the introduction of a requirement on main contractors to pay sub-contractors within 10 days of receipt of valid invoices, with a view to increasing the borrowing potential and/or easing the cash flow pressures on small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises. (Paragraph 172)

18. The Committee recommends that the Minister of Finance and Personnel, in conjunction with the Minister of Enterprise, Trade and Investment, gives careful consideration to the establishment of a public procurement brokerage service as identified by the Ulster Community Investment Trust, which could also act as a “one-stop shop" for the social economy sector in terms of availing of public procurement opportunities. (Paragraph 176)

19. The Committee recommends that the Central Procurement Directorate reviews existing procurement guidance, in conjunction with local stakeholders, with a view to ensuring that it is fit for purpose and brought together as a central online resource for public sector procurement, which is linked to the eSourcingNI web portal. (Paragraph 184)

20. Whilst acknowledging that, whenever public funds are at stake, proper audit, monitoring and accounting arrangements are an unavoidable necessity, the Committee recommends that the Department of Finance and Personnel, in conjunction with the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment, takes steps to ensure that proportionate monitoring arrangements are applied, which are sympathetic to the ethos and needs of the social economy sector. (Paragraph 188)

21. The Committee is strongly of the view that pre-qualification processes and criteria should not be so burdensome as to deny both small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises the opportunity to develop their business and thereby benefit the local economy. As such, the Committee recommends both that the principle of proportionality (i.e. the resources required to bid should be proportional to the size of contract) should be embedded into all public procurement tendering exercises and that the next review of Centres of Procurement Expertise, due to take place in 2013, places a particular focus on progress in improving pre-qualification processes. (Paragraph 198)

22. The Committee welcomes the development of a standardised pre-qualification questionnaire for works contracts, which is currently being taken forward by the Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland. The Committee recommends that, once an agreed approach has been established, the Procurement Board considers its application to all procurement sectors and across all Centres of Procurement Expertise. (Paragraph 200)

23. In noting that the Construction Industry Forum for Northern Ireland is actively considering the weighting of relevant experience in the assessment process for works contracts, the Committee recommends that the Procurement Board considers the potential for applying any lessons arising from this work across the other Centres of Procurement Expertise and to supplies and service contracts. (Paragraph 204)

24. The Committee recommends that feedback mechanisms across all the Centres of Procurement Expertise are standardised and aligned with good practice, with greater monitoring to ensure effectiveness. (Paragraph 208)

25. The Committee recommends that the Central Procurement Directorate provides specific guidance and support to government purchasers in relation to the social economy, including on Special Contracts Arrangements. Also, as more social enterprises enter the procurement market, tailored advice should be available to those organisations that would be eligible for supported status (i.e. where more than 50% of employees are registered as severely disabled). (Paragraph 212)

Maximising Social Benefit

26. The Committee senses a reticence amongst local commissioners and purchasers to pursue social benefit through procurement, which may be linked to a need for greater clarity both on the Executive’s policy intention in this area and on the definition and measurement of ‘social value’. (Paragraph 244)

27. The Committee recommends that the Executive translates its Programme for Government/Public Service Agreement commitments in this area into a clear policy directive on procuring social benefit, which sets out the priorities that should be pursued by the Procurement Board, the Centres of Procurement Expertise and individual commissioners and purchasers. The Committee further recommends that this policy directive, which should be underpinned by the necessary legal guidance, is reflected, as appropriate, in departmental business objectives, in the forthcoming Northern Ireland Public Procurement Handbook and in the personal performance objectives of commissioners and procurement professionals. (Paragraph 245)

28. The Committee notes the growing body of guidance on procuring social benefit and, in particular, welcomes the practical toolkit which has been published recently on behalf of the Strategic Investment Board. However, the Committee is concerned that this resource will be underutilised without the necessary policy direction from the Executive. (Paragraph 246)

29. In the meantime, and given the positive evaluation of the Procurement Board’s Pilot Project on Utilising the Unemployed in Public Contracts, the Committee recommends the use of clauses setting quotas for employing apprentices and the long-term unemployed in all suitable public contracts. Also, in recognising the need for further empirical evidence on best practice use of social clauses, the Committee recommends that the Central Procurement Directorate makes a rigorous assessment of the social clauses applied in recent construction contracts, with a view to identifying lessons and opportunities for further initiatives in this regard. (Paragraph 247)

30. The Committee is strongly of the view that, in future, value-for-money assessments must strike a balance between short-term monetary considerations and longer-term economic, social and environmental costs and benefits. This is especially important in the context of the constrained public expenditure environment, when departments must not lose sight of the Executive’s strategic priorities. As such, the Committee calls on the Department of Finance and Personnel to put in place a suitable model for systematically measuring, evaluating and incorporating wider social value considerations within economic appraisals and business cases, and which will inform public procurement processes. Moreover, the Committee recommends that socially responsible procurement should be included as a scored criterion in the next Centre of Procurement Expertise accreditation exercise. (Paragraph 253)

Building Capacity for Purchasers and Suppliers

31. The Committee is conscious that capacity building for both purchasers and suppliers will also be vital to maximising the outcomes from public procurement. The Committee is mindful that, whilst the Department of Finance and Personnel, through the Procurement Board, must take the lead in developing the capacity of purchasers, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment has lead responsibility in terms of the small business and social economy sectors. (Paragraph 258)

32. The Committee urges the Procurement Board to consider the possibilities for introducing licentiate arrangements for procurement professionals across the public sector, with a view to ensuring greater uniformity in the professional competencies of purchasing staff. In addition, the Committee considers that it is essential that the continual professional development of procurement personnel should include awareness of the benefits of doing business with both the small business and the social economy sectors. (Paragraph 265)

33. The Committee calls on the Minster of Finance and Personnel to liaise with the Minister of Enterprise, Trade and Investment to ensure that sufficient funding is in place for measures to build the capacity of smaller enterprises to access the public sector supply chain. The Committee sees a vital role for the Central Procurement Directorate in contributing to procurement training and development for both small and medium sized enterprises and social economy enterprises and will wish to be apprised of plans for taking this forward. (Paragraph 274)

34. The Committee endorses the concept of a “Procurement Exchange Programme" and urges the Procurement Board to bring forward options on how this might be developed so as to facilitate cross-sectoral training and knowledge transfer across the public sector and the private sector. (Paragraph 277)

Local Government Procurement

35. In welcoming moves towards a more collaborative approach to local authority procurement, the Committee considers that, in the event of the proposed new local authority Centre of Procurement Expertise being established, then appropriate linkages should be developed with the central government procurement structures. Whilst recognising the independence and autonomy of local councils, the Committee urges greater synergy between central and local government purchasing policy and practice, with a view to achieving consistency in the application of good practice procurement across the public sector. (Paragraph 287)

Collaborative Procurement and Efficiencies

36. The Committee concludes that there is scope for more strategic co-ordination of the public procurement landscape in Northern Ireland to realise efficiencies, not only between central and local government but also in terms of arms-length public bodies. Moreover, the Committee proposes that the Executive explores opportunities to achieve additional efficiencies through collaborative government procurement on a North-South and East-West basis. (Paragraph 295)

37. The Committee reiterates its call for a new target to be set for achieving further efficiencies from public procurement, to include a monetary value and baseline for such savings, with an associated implementation plan which links to individual departmental efficiency delivery plans. (Paragraph 296)

38. In calling for a further efficiency drive through collaborative procurement, the Committee emphasises the need for such collaboration to be co-ordinated at a strategic level by the Procurement Board to avoid counterproductive localised efficiencies being pursued which have an adverse effect on the efficiency of the wider public sector and/or are detrimental to the local economy. (Paragraph 297)

39. The Committee recommends that, in reviewing the data capture and management information systems within Centres of Procurement Expertise, the Procurement Board also considers the position more widely across departments to ensure that robust systems are in place to facilitate evidence-based decision making in terms of the identification and monitoring of procurement efficiencies. (Paragraph 298)

Litigation and Lessons Learned

40. Given the cost of litigation and the associated disruption to capital projects and other procurement exercises, the Committee believes that a conciliatory approach is needed in resolving procurement conflicts and considers that the absence of an independent mediator between purchaser and supplier is a key deficiency within the procurement process in Northern Ireland. As such, the Committee recommends that the Procurement Board urgently examines the possibility of providing for a “Supply Chain Ombudsman" function in Northern Ireland, which would, amongst other things, fulfil this important mediation role. The Committee also believes that the proposal for licentiate arrangements for procurement professionals could help to reduce the level of litigation arising from failure to meet legal obligations. (Paragraph 312)

Public Procurement Governance Arrangements

41. The Committee calls on the Procurement Board to bring forward options for strengthening and formalising the relationship between the Central Procurement Directorate and the other Centres of Procurement Expertise, with a view to ensuring consistency in applying good practice procurement in support of the Executive’s key priorities. (Paragraph 319)

Introduction

Background

1. The Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) has a lead role in public procurement, with the DFP Minister chairing the inter-departmental Procurement Board, and the Department’s Central Procurement Directorate (CPD) supporting the Board in the development and implementation of new procurement policy. CPD also provides a centralised professional procurement service to the Northern Ireland (NI) public sector and monitors and mentors the work of seven other Centres of Procurement Expertise (CoPEs).

2. Expenditure on public procurement by CPD and the other CoPEs represents approximately £2.4 billion[1] per annum, nearly 25% of the Executive’s budget. The services, supplies and works which are subject to the procurement process are also wide ranging. Government contracts include catering, transport, banking, construction, printing, telecoms, ICT (hardware), travel, vehicle maintenance, advertising, stationery, furniture/office equipment supply, security, messenger services, economic/research consultancy, staff recruitment, PR and event management, clinical and laboratory products, environmental monitoring equipment, and even helicopter hire.

3. In addition to the Executive’s annual expenditure of £2.4bn, the NI public procurement market also includes an estimated spend of £300m per annum on local government purchasing.[2] In terms of the all-island context, the combined procurement market is worth around €19 billion (£15.2 billion).[3] The potential is even greater in terms of the opportunities for NI enterprises to also engage the Great Britain (GB) public procurement market, estimated at over £175 billion,[4] and the wider European Union (EU) market which is estimated at € 2000 billion (£1600 billion) in 2007.[5]

4. The Committee recognises that, given the profile of the local business sector, it can be expected that Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) will win the majority of public sector contracts in NI. However, as the Inquiry report will demonstrate, a sound rationale exists for encouraging new entrants into the procurement market from the small and micro enterprise sector and for enabling such firms to compete for higher value contracts. The Inquiry found that evidence exists internationally in support of this rationale. For example, the European Code of Best Practices Facilitating Access by SMEs to Public Procurement Contracts[6] highlights the benefits of increasing SME involvement in public purchasing, commenting that it will “result in higher competition for public contracts, leading to better value for money for contracting authorities. In addition to this, more competitive and transparent public procurement practices will allow SMEs to unlock their growth and innovation potential with a positive impact on the European economy."[7]

5. The Committee notes that a 2008 consultation on the Small Business Act for Europe[8] suggested that the most important problem that European SMEs are facing, and which prevent their growth, is access to public procurement. Also, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI) Matrix report has noted that across the EU, initiatives to encourage or facilitate the participation by small companies in government procurement in general have been very limited.[9]

6. The Minister of Finance and Personnel, in a document entitled Northern Ireland Public Procurement Policy, highlighted that “public procurement expenditure can be used to best effect to maximise the outcomes for the people of Northern Ireland".[10] The Committee for Finance and Personnel concurs with this view.

7. The public procurement process is complex and heavily regulated. Procurement law is driven by European directives, which are implemented in NI through regulations, including the Public Contracts Regulations 2006.[11] The regulations apply to all public bodies which are largely owned, managed or financed through public funds. This includes government departments and their agencies, non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs), hospitals and health sector purchasers, housing associations, education boards and institutions, various non-government organisations and district councils.

8. Other organisations in receipt of government sponsored funding for more than 50% of a project may also fall under the regulations for public procurement. For example, a community organisation seeking to build new premises must undergo a procurement process if government grant aid makes up more than half of the required funding package.[12]

9. Following an initial consideration of public procurement policy and practice the Committee identified a range of concerns. These included issues regarding the robustness of the process; compliance with legal requirements; the extent to which government contracts make provision for social clauses; the scope for increasing the capacity of SMEs and Social Economy Enterprises (SEEs) to compete for public contracts; and the consequences of undue delays in progressing procurement contracts, especially in terms of the impact on the construction sector of delays in planned capital expenditure.

Scope and Terms of Reference

10. At its meeting on 19 November 2008, the Committee agreed its terms of reference for an Inquiry into Public Procurement Policy and Practice in NI. Given the range and scale of public procurement, members chose to focus on specific aspects of the policy and process. Therefore the Inquiry terms of reference emphasise the end-user experience of SMEs and the social economy sector.

11. The Committee sought to:

a) examine the experience of SMEs and SEEs in tendering for and delivering public contracts;

b) consider the nature, extent and application of social clauses within public contracts;

c) identify issues to be addressed and which are within the remit of DFP;

d) assess progress by DFP in achieving associated objectives and targets, including those contained in the Programme for Government (PfG) and related Public Service Agreements (PSAs); and,

e) make recommendations to DFP for improvements to public procurement policies and processes, aimed at increasing access to opportunities for SMEs and SEEs and maximising the economic and social benefits for the local community, whilst taking account of the principles governing public procurement.

12. The Committee therefore expects that the recommendations arising from this Inquiry report will help to realise additional economic and social benefits for the local community from the public procurement process.

The Committee’s Approach

13. As a starting point, to inform its deliberations, the Committee received an introductory briefing from CPD officials at its meeting on 1 October 2008. At the same meeting, members also heard from Capita and the Ashton Community Trust, on the use of social clauses within procurement contracts, and the positive impact these can have on local communities. These evidence sessions informed the Committee’s terms of reference for the Inquiry.

14. The Committee issued a public call for written evidence in local newspapers and a total of 35 submissions were received by 27 February 2009. These reflected the broad spectrum of stakeholders involved in a variety of procurement processes throughout NI including SEEs, SMEs, construction companies, professional bodies and representative organisations. These submissions are included in the report at Appendix 3.

15. Following consideration of the submissions to the Inquiry, the Committee identified a number of organisations which were invited to provide oral evidence, and these evidence sessions took place between May and October 2009. The Official Reports of evidence sessions are included at Appendix 2, while other memoranda and papers from key stakeholders are included at Appendix 5.

16. At various stages throughout the Inquiry the Committee requested both written and oral evidence from officials in CPD. The Official Reports of these oral evidence sessions are also included at Appendix 2, while written papers and memoranda are available at Appendix 4. The Committee acknowledges the constructive engagement with CPD officials throughout the course of the Inquiry and understands that several of the issues raised are already being considered by them, in conjunction with industry groups. In addition to the written and oral evidence, the Inquiry was underpinned by a literature review of good practice procurement, including international examples where appropriate.

17. Given the wide range of stakeholders involved in the procurement process in NI and the breadth of issues raised in the oral and written evidence, the Committee agreed, at its meeting of 17 June 2009, to host a Stakeholder Conference. Following a procurement process, the Social Research Centre was appointed to facilitate the event.

18. The Conference, Maximising the Economic and Social Benefits from Public Procurement in Northern Ireland, was designed to supplement the Inquiry evidence base by:

- gathering further evidence to assist the Committee in prioritising the key issues to be addressed;

- generating further ideas for improving access for SMEs and SEEs to the public procurement market and in terms of achieving social aims; and,

- testing stakeholder opinion on the ideas put forward through an active consultation process.

19. Held on 21 October 2009, the Conference represented an additional and alternative approach to gathering inquiry evidence from the usual process of taking written submissions and holding oral hearings. The format included breakout sessions, short inputs from recognised procurement commentators and digi-voting[13] on priorities and recommendations. The Committee would like to thank Eileen Beamish of the Social Research Centre for facilitating the design and delivery of the Stakeholder Conference, which added value to the evidence base of the Inquiry.

20. Around 100 participants attended the conference, representing government purchasing bodies, SMEs, SEEs and umbrella bodies. Several “procurement commentators" also contributed, including: Paul Davis, Dublin City University; Professor Andrew Erridge, University of Ulster; Jenni Inglis, Social Return on Investment Network; Frank McGlone, Procurement Adviser; Dr Gordon Murray, Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA); and Martin Sykes, Chief Executive of Value Wales. They highlighted best practice and learning from other jurisdictions, whilst also challenging the practices and perceptions of both suppliers and purchasers. The Committee acknowledges the contribution and insight which each of the commentators has brought to this process.

21. The Committee invited two leading academics, Professor Chris McCrudden, Professor in Human Rights Law, Lincoln College, University of Oxford; and Dr Aris Georgopoulos, Lecturer in Law, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Nottingham, to comment on the output from the Stakeholder Conference. The Committee welcomes these contributions which have been included, along with the full Conference Report, at Appendix 7 and referenced in the body of the Inquiry Report as appropriate.

22. Assembly Research also assisted the Committee by providing a number of research papers on a range of pertinent issues raised, in addition to background briefing. All Assembly Research papers relating to the Inquiry are available at Appendix 6.

23. The breadth and range of issues brought to the attention of the Committee reflects the broad reach and impact of procurement policy and practice throughout NI. The Committee extends its gratitude to all those from across the spectrum of the procurement community for giving evidence, both oral and written, participating in the Stakeholder Conference, and assisting in the Inquiry process.

24. In welcoming the constructive way in which stakeholders have contributed to the Inquiry and the positive proposals that have been suggested, the Committee also acknowledges that there may have been organisations reluctant to provide evidence, to avoid a perception of companies “biting the hand that feeds them". The Committee anticipates that the views of such businesses, however, have been reflected in the submissions, both written and oral, from the various umbrella and industry organisations working in this area.

Themes from the Evidence

25. The ‘Consideration of the Evidence’ section of the report reflects the themes emerging from the Inquiry evidence and discussions at the Stakeholder Conference. Much of the evidence can be grouped under the following themes:

i. Improving Policy and Processes

This includes concerns about the use of frameworks; onerous application processes often involving duplication of information; sourcing opportunities to bid; pre-qualification criteria; exclusion from contracts; and, complex tendering procedures. Given the broad scope of issues raised, this theme can be further broken down into the following areas:

a) Framework Agreements and Contracts

b) Opportunities to Bid

c) Tendering and Delivering

“Improving Policy and Processes" is discussed at paragraphs 93 – 212.

ii. Maximising Social Benefit

A key Inquiry aim was to consider the nature, extent and application of social clauses within public contracts. This brought responses from all stakeholders and included issues around definition; monitoring and evaluation; and, policy direction. “Maximising Social Benefit" is discussed at paragraphs 213 – 253.

iii. Building Capacity for Purchasers and Suppliers

Although not directly highlighted in the Inquiry terms of reference, building capacity for both purchasers and suppliers was an important issue emerging from the evidence. This included the need for cultural change within purchasing bodies, but also a call for local SMEs and SEEs to develop the appropriate skills necessary to compete for government contracts. This area is considered further at paragraphs 254 – 277.

26. These three broad themes informed the structure and content of the Stakeholder Conference (see Programme and Report at Appendix 7). The format of the Conference allowed the Committee to learn about further issues of concern to the local procurement community and also to hear suggestions for improvements.

27. A survey commissioned by the FSB during the course of the Committee Inquiry indicated that the majority of SMEs who responded, bid for contracts below £50k, and this mostly originates from local government.[14] While not directly within the remit of the Committee, a recurrent theme throughout the Inquiry has been the Review of Public Administration (RPA) and the potential impact on procurement policy and practice at local government level.

28. Given that the Inquiry terms of reference determined that the Committee would “make recommendations to DFP for improvements to public procurement policies and processes", it is appropriate for the Committee to consider the potential role of local government purchasing amongst the other concerns that have arisen. The Inquiry findings relating to local government procurement will be communicated to the Department of the Environment (DoE), via the respective Assembly committee, and to the Northern Ireland Local Government Association (NILGA) for consideration. Discussion on procurement and local government can be found at paragraphs 278 – 287, with an Assembly Research paper included at Appendix 6. The case for collaborative procurement and the scope for further efficiencies is examined at paragraphs 288 – 298.

29. Of particular concern to the Committee during the course of the Inquiry was the number of procurement exercises that are the subject of legal proceedings. Members received updates from CPD officials on the nature and progress of these cases, including lessons learned. This area is dealt with in the report at paragraphs 299 – 312.

30. Finally, the wider role of CPD in relation to public sector procurement was an issue brought to the attention of the Committee throughout the Inquiry. While CPD primarily has an advisory role, it appears that there is scope for greater consistency across public sector procurement processes. Further consideration of governance issues is discussed at paragraphs 313 – 319.

31. Before discussing the main themes from the evidence, however, it will be helpful to consider the context of the Committee Inquiry, in terms of the wider public procurement environment.

Consideration of the Evidence

The Public Procurement Environment

European Legal Framework for Procurement[15]

32. The rules governing EU public procurement directly affect how public bodies can purchase supplies, works and services. Such purchases by public bodies represent about 16% of the EU’s total gross domestic product (GDP) and in 2007 the value was estimated at €2,000 billion (£1,600 billion) (including procurements both above and below thresholds), while in 2006 nearly 32,000 contracting authorities published contracts worth €380 billion (£304 billion). Procurement is therefore regarded as a key single market issue.

33. Government purchasing bodies must consider three aspects of the EU legal framework when conducting procurement exercises, including primary and secondary legislation and case law. The primary law is essentially the EC Treaty within which the following three basic principles (sometimes referred to as the ‘fundamental principles’) are enshrined:

i. Openness and transparency of award procedures;

ii. Genuine competition in the award of contracts; and

iii. No unlawful discrimination on the grounds of nationality.

34. 34. One of the main consequences of these fundamental principles is that EU member states are not in a position to favour indigenous business over companies from elsewhere in the EU. Member states must be careful that social or ethical considerations do not operate as a disguised barrier to the free movement of goods and become a form of protectionism. This has recently been reiterated by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the Rüffert case[16]. Contracting authorities must pay particular attention to this, or risk a legal challenge.

35. Secondary law relates to European directives which must be transposed by member states into national law. The most relevant of these is Directive 2004/18/EC of the European Parliament and Council of 31 March 2004, on the co-ordination of procedures for the award of public works contracts, public supply contracts and public services contracts. This was transposed in NI through the Public Contracts Regulations 2006 (Statutory Instrument 2006 No.5).[17] The aim of the legislation is to reduce the administrative burden and associated costs, make procurement systems more transparent and easier for SMEs (in particular) to access, and encourage the use of IT systems to simplify the tendering process.

36. The regulations apply to all public sector bodies which are largely owned, managed or financed through public funds. This includes:

- All central government departments (including Executive Agencies)

- District Councils

- Various Non-Government Organisations (NGOs)

- Housing associations

- Hospitals and health sector purchasers

- Educations bodies including: Boards, Secondary, Further and Higher institutions

- Grant-aided procurement (projects in receipt of public funds over 50%).

37. Thirdly, there is the case law of the European Courts. The introduction of the ‘Alcatel’ 10-day mandatory standstill period following a contract award is one of the more recent cases. Following this ECJ ruling a contracting authority must allow at least 10 days between the date of despatch of information to all bidders relating to the award decision, and the date on which it proposes to enter into the contract, or conclude the framework agreement. Unsuccessful bidders then have an opportunity to receive feedback and, if appropriate, query the decision of the contracting authority.[18] This has now been superseded by the ‘Remedies Directive’[19] which came into force in December 2009 and places greater emphasis on the standstill period.

The Scope of Public Procurement Practice

38. As already indicated, in 2008-09 expenditure on public procurement in NI accounted for approximately £2.4 billion of supplies, services and construction works in 2008-09 representing nearly 25% of all public expenditure.[20]

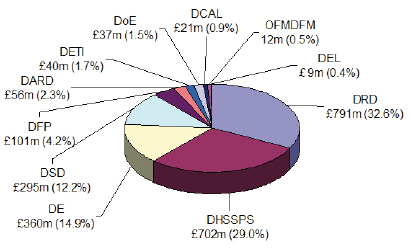

39. Figure 1 highlights the spread of procurement spend across all Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) departments in 2008-09. This does not include local government spend which is accounted for individually by councils and is not monitored by CPD.

Figure 1: Expenditure on public procurement across Northern Ireland Civil Service Departments[21]

40. The three largest spending departments are Regional Development, Health and Education. This reflects expenditure not only on large infrastructure projects but also on supplies and services. The research paper Public Procurement and the Social Economy included at Appendix 6, highlights the range of procurement expenditure incurred by Departments, Agencies and NDPBs from 2005 -2008. A comparative table on procurement spend across Departments over those three years is included in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Public Procurement Expenditure incurred by Departments, Agencies and NDPBs by Category 2005 – 2008[22]

| Category | 2005/06 £m |

2006/07 £m |

2007/08 £m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction/Maintenance Services | 794 |

711 |

897 |

| Medical/Surgical Equipment and Supplies | 187 |

186 |

235 |

| Consultancy Services | 121 |

102 |

115 |

| Energy | 100 |

125 |

140 |

| Public Utilities | 77 |

71 |

|

| Transport and Travel Services | 53 |

63 |

72 |

| Repair/Maintenance Services | 53 |

60 |

67 |

| Plant and Machinery (including tools and equipment) | 45 |

43 |

59 |

| Facilities Management | 44 |

52 |

63 |

| Rental, Leasing or Hire Services | 42 |

24 |

54 |

| Office Machines and Supplies | 41 |

72 |

99 |

| Transportation Equipment | 30 |

61 |

78 |

| Postal and Telecoms Equipment and Supplies | 29 |

35 |

36 |

| Food Stuffs | 27 |

27 |

37 |

| Chemicals/Reagents | 23 |

21 |

21 |

| Financial Services | 22 |

17 |

21 |

| Furniture and Fittings | 13 |

17 |

19 |

| Printing/Reprographic Services | 13 |

14 |

14 |

| Environmental Services | 11 |

10 |

14 |

| Publications | 10 |

14 |

24 |

| Clothing and Accessories | 7 |

7 |

8 |

| Land | 19 |

||

| Advertising | 16 |

||

| Recruitment and Personnel Services | 15 |

||

| Research and Development | 8 |

||

| Public Relations (including events/conferences) | 6 |

||

| Other Expenditure | 70 |

162 |

65 |

|

Totals |

1812 |

1895 |

2202 |

41.The Committee recognises the business opportunities presented to indigenous enterprises by the substantial expenditure on public procurement in the NI, all-island, GB and wider EU markets. However, the Committee is also mindful that the NI business economy overwhelmingly comprises smaller enterprises, many of which consider that the public procurement process requires more time, effort and cost than business would allow.[23] As such, the Committee considers that it is incumbent upon the Executive and the Assembly both to create a public procurement environment that facilitates our smaller enterprises in realising their full potential and which maximises the economic and social impact from expenditure on procurement.

Public Procurement Principles

42. In its evidence, CPD explained that the administration of public procurement in NI is governed by twelve guiding principles agreed by the Executive. These are:

i. Accountability,

ii. Competitive Supply,

iii. Consistency,

iv. Effectiveness,

v. Efficiency,

vi. Fair-dealing

vii. Integration,

viii. Integrity,

ix. Informed decision-making,

x. Legality,

xi. Responsiveness, and

xii. Transparency.

The Executive considers that these principles reflect the statutory obligations relating to equality of opportunity and sustainable development and link to the PfG. More information on the twelve principles can be found at Appendix 4.[24]

43. The Committee has been advised that the roles and expectations on commissioners and purchasers which arise from the twelve principles will be further clarified in the “Northern Ireland Public Procurement Handbook", currently being developed by CPD. The Committee welcomes this initiative as it believes that, given the aspirational terms in which the principles are cast, purchasers could find them difficult to interpret and implement without more specific instruction.

44. The Committee notes that the CPD guidance defines “best value for money" as “the optimum combination of whole life cost and quality (or fitness for purpose) to meet the customer requirements". More particularly, the guidance states that:

“While ‘best value for money’ is the primary objective of procurement policy, this definition allows for the inclusion, as appropriate within the procurement process, of social, economic and environmental goals, the three pillars of sustainable development".[25]

Also, the Committee notes with interest that the CPD guidance advisesthat when the twelve guiding principles“have been satisfied to an acceptable level then best value for money can be said to have been achieved".[26]

45. As outlined later in the report, evidence presented to the Committee during the course of the Inquiry suggests that, in comparative terms, public procurement practice in NI has a predominant focus on compliance (i.e. the Legality principle) and on narrow value-for-money considerations. While these considerations are undoubtedly important, the Inquiry report highlights the need for further development in good practice, which will see more weight given to some of the other guiding principles. In terms of the external perception, in its submission to the Inquiry, CBI highlighted the results of a survey which it carried out of 157 NI-based suppliers in 2008, which showed that 61% of respondents did not think that public procurement is resulting in value for money, compared with 16% who did. Some 64% felt that further fundamental changes are required.

46. The Committee notes that an underlying theme from the Inquiry evidence suggests that government evaluations and appraisals, including as part of the procurement process, tend not to attach sufficient weighting to longer-term qualitative/non-monetary benefits for the wider economy and society, which can be realised from capital investments and procurement exercises.

47. The Committee is aware that the “Integration" principle advocates that “in line with the NI Executive’s policy on joined-up government, procurement policy should pay due regard to the Executive’s other economic and social policies, rather than cut across them". Moreover, the CPD guidance highlights that one implication of adopting the twelve principles for the Executive’s policy on public procurement will be that “wider economic, social and environmental strategies and initiatives of the Executive should be more closely integrated into procurement policy".[27] However, the evidence presented to the Inquiry leads the Committee to conclude that there is insufficient integration in this regard and that a more strategic and widely defined consideration of “value for money" is needed, which has a focus on longer-term economic and social well-being.

48. In addition to the Integration principle, the Inquiry report will also highlight the need for greater emphasis on Consistency (i.e. to ensure uniformity of approach across CoPEs), Competitive Supply (i.e. greater action to realise benefits of SME involvement), Informed decision-making (i.e. to establish robust management information systems and to take sufficient account of social value) and Responsiveness (i.e. to the needs of SMEs and SEEs).

Organisational structures for the development and implementation of Procurement Policy in NI

The Northern Ireland Executive[28]

49. The development and implementation of procurement policy rests at various levels within government. The NI Executive is responsible for agreeing overall public procurement policy including the adoption of the twelve procurement policy principles. In its Programme for Government 2008 – 2011, Building a Better Future, the Executive highlighted the positive role that procurement has in furthering cross-cutting, sustainable development and socio-economic objectives.

50. The Committee notes that “growing a dynamic, innovative economy" is the cornerstone of the PfG; and, that there is a particular emphasis on “growing the private sector including small and medium enterprises" and “developing the social economy."

51. Within the PfG, the Executive recognises “the important contribution that such local economic activity promotes in both social objectives and in sustainable community development"[29]; and that there is a commitment to ensure that any government reforms and restructuring will be compliant with recognised best practice in social procurement guidelines.

52. The Committee welcomes the recognition within the PfG of the significant role that public procurement policy can play in advancing the overall aims and objectives of government, including achieving policy objectives under the cross-cutting theme of sustainable development[30] and in tackling patterns of socio-economic disadvantage[31].

53. Public Service Agreement (PSA) 11 specifically addresses these issues with its objective to “support the wider Public Sector in taking account of sustainable development principles when procuring works, supplies and services". In its ongoing scrutiny of DFP’s progress against PSAs in the PfG, the Committee will continue to closely monitor those PSAs specifically addressing procurement.

54. Detailed actions include the integration of sustainable development priorities; increasing access to public procurement opportunities for SMEs and SEEs; monitoring and reporting on compliance with guidance on integration of equality and sustainable development priorities within the procurement process; and basic training for all procurement staff in sustainable procurement processes.

55. Other PSAs with a focus on procurement practice include PSA 20 “Improving Public Services" which highlights “improved procurement practice" as a key target within the objective of taking forward the modernisation of the health and social services sector.

56. PSA 21 “Enabling Efficient Government" also impinges on procurement policy and practice in NI, as objective 5 commits to delivering the most economically advantageous outcomes in government procurement.

57.The Committee believes that the implementation of the recommendations arising from this Inquiry will help to achieve key objectives of the Executive’s PfG, not least the emphasis on “growing the private sector including small and medium enterprises’ and ‘developing the social economy". As a prerequisite, however, the existing drivers for public procurement will need to be realigned in support of the Executive’s economic, social and environmental priorities. In particular, this will require a more balanced application of the twelve guiding principles governing the administration of public procurement in NI, which, in turn, will help achieve “best value for money". This will be discussed in more detail later in the report.

Procurement Board

58. A Procurement Board, chaired by the Minister of Finance and Personnel, comprises the Permanent Secretaries of the 11 NI Departments, the Treasury Officer of Accounts, the Director of CPD and two external experts. The Board has particular responsibility in respect of developing overarching public procurement policy for NI Departments, their agencies and other public bodies. The Board is responsible to the Executive and accountable to the NI Assembly.

59. Procurement policy and practice in NI has been under increased Assembly scrutiny in recent months as a consequence of this Inquiry. The Procurement Board will wish to carefully consider the recommendations of this Report and the Committee looks forward to receiving a formal response to the findings and recommendations.

Central Procurement Directorate

60. CPD was established within DFP in April 2002 to support the development and implementation of public procurement policy and provides a centralised professional procurement service to the NI public sector. While CPD is available to local government purchasing bodies for advice and guidance, there is no imperative to engage with CPD during procurement exercises.

Centres of Procurement Expertise

61. In addition to CPD, seven other CoPEs exist to provide a more integrated service to bodies throughout the public sector. These are:

- Roads Service

- Northern Ireland Water

- Health and Social Care Northern Ireland – BSO Procurement and Logistics

- Northern Ireland Housing Executive

- Health Estates

- Education and Library Boards (to be replaced by the Education and Skills Authority).

- Translink[32].

62. Public procurement policy in NI requires that the competency of CoPEs is reviewed by the Procurement Board on a periodic basis. The first review was carried out by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) in 2005 and a second review took place in 2009, also by PwC.[33] The twelve procurement principles are used to assess CoPEs against best value for money in their reaccreditation. This area is discussed in more detail later in the report, under the section on Public Procurement Governance Arrangements.

Procurement Practitioners’ Group

63. There also exists a Procurement Practitioners’ Group (PPG) where representatives from CPD and the other CoPEs meet to inform, test and develop policy and, where appropriate, operational issues.

64. Further information on the relationships and roles of the Executive, the Procurement Board, and the Procurement Practitioners’ Group can be found at Appendix 4.

Construction Industry Forum for NI Procurement Task Group

65. The Committee also notes the work of the Construction Industry Forum for NI Procurement Task Group (CIFNI PTG), which was recently formed in response to the economic downturn. Several principles underpinning the Group reflect the thrust of this Inquiry, including: maximising the opportunities for enterprises to benefit from public sector construction contracts through participation in the supply chain; reducing the cost and timescale of the pre-qualification process; and reducing the costs of tendering.

Social Economy Enterprise Procurement Group

66. The Committee notes from a recent draft of the Social Economy Enterprise Strategy 2010-11, that DETI, supported by CPD, will work with the Social Economy Network (NI) Ltd (SEN) to facilitate two meetings per year of the Social Economy Enterprise Procurement Group.[34] This will aim to increase awareness of the public sector tendering process amongst social enterprises and break down barriers to procurement.

Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in NI

67. SMEs in NI are primarily characterised by staff headcount, although the European Commission publication, The new SME definition: User Guide and Model Declaration,[35] also allows for annual turnover and balance sheet total to be taken into account. The Annual Report on EU Small and Medium Sized Enterprises notes that SMEs range from self-employed bookkeepers without personnel, to fast-growing, innovative and much-internationalised ICT firms with 200 employees, and everything in between.[36]

68. For the purposes of the Committee Inquiry, SMEs have been categorised as follows:

- Micro <10 employees

- Small <50 employees

- Medium <250 employees

69. In its evidence to the Inquiry, the FSB highlighted that public bodies may consider that “they have 100% submission from the SME sector to tender notices, and a 100% success rate of award of contracts to SMEs – given that the standard definition of an SME relates to all businesses employing up to 250 people". During the Inquiry, it became clear that there is a lack of consistency in the definition of an SME used by buyers in the public sector market, an issue that was also highlighted, in terms of the all-island context in the recent InterTradeIreland report.

70. The Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR) – Edition 10 (20 June 2008)[37] shows that, of the 72,550 SMEs in NI, 7,870 businesses had more than 10 employees and, of this figure, only 1,240 employed more than 50 people. The remaining 64,680 (89%) businesses are classed as micro-businesses, employing fewer than 10 people. Fifty percent of all businesses in NI are registered as ‘Sole Proprietors’.[38] Micro-businesses therefore have a particularly prominent place in the local economy.

71. In recognising that nearly 90% of small businesses in NI are micro-businesses, the Committee would wish to highlight the concerns of those who responded to the Inquiry requesting clarity on the definition of SMEs. As such,the Committee recommends that the Procurement Board, in conjunction with DETI, considers refining the definition of SMEs in the NI context, paying particular attention to those currently identified as small, or micro-businesses, when exploring ways of boosting access to procurement opportunities by local businesses.

72. The Committee is aware that the high proportion of small and micro enterprises in the local business sector could be viewed as a structural weakness in the NI economy. Evidence at an EU level, for example, shows that SMEs, especially micro enterprises, have a lower labour productivity than large enterprises and contribute a considerably lower share to value added than to employment. That said, the Committee also notes that, at a UK level, a report from the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform has found that “the small business sector has become more dynamic" and that “productivity growth in small firms has exceeded that in large firms since 1998". [39] Also, the Committee is conscious that the EU research highlights compelling empirical evidence of how SMEs can have a positive impact on economic growth trends, particularly from a longer-term perspective.[40]

73. The Committee notes from this recent EU research that SMEs in general, and micro enterprises in particular, “contribute to the creation of new employment at a much higher rate than do large firms".[41] Also, in the context of developing the “knowledge economy" in NI, the Committee notes that SMEs contribute to the dynamism and innovative performance of an economy by providing the vehicle for “knowledge spill-over entrepreneurship", in terms of implementing and commercialising the new knowledge generated from investment in research at universities and other research institutes.[42]

74. The recent Independent Review of Economic Policy (IREP) indicates that local businesses “will remain the bed-rock of the NI economy."[43] The report also notes that NI is dominated by small firms, primarily due to a large agricultural sector, but also reflecting more small firms than the UK average in construction, retail, transport and extraction. [44] It is the view of the authors of the IREP that “it is important that in practice, public policy interventions/resources are increasingly targeted at overcoming the obstacles to business growth."[45]

75. The Committee is also aware that HM Treasury’s Office of Government Commerce (OGC) has concluded that much could be gained by enabling a greater number of smaller businesses to compete in the public sector supply chain. OGC cites benefits for both the smaller businesses and the public sector. In the case of smaller businesses, they can gain by having greater access to a large and stable market. The benefits for the public sector include: better value for money (i.e. greater competition reduces costs from all suppliers and the lower overhead costs of smaller business can result in lower prices); better quality of service; and innovative business solutions.[46] On the latter issue, both the DETI Matrix Group and Sir David Varney’s Review of the Competitiveness of NI have highlighted how government procurement can play an important role in driving SME innovation and growth.[47]

76. The Committee notes that the aforementioned benefits from greater participation by smaller enterprises in the government supply chain were reiterated in a report on Evaluating SME Experiences of Government Procurement, published jointly by CBI, FSB and the British Private Equity and Joint Venture Capital Association in 2008.[48] Also, the Committee is conscious that, as far back as 2001, the Review of Public Sector Procurement in NI recognised both the benefits of encouraging SME access to public contracts and the associated barriers.

77. In addition to the direct benefits from greater participation by smaller enterprises in the local procurement market, the Committee also understands that wider economic gains, in terms of increased Gross Value Added (GVA) in NI, could accrue from local SME entry into other public procurement markets, including RoI and GB.[49]

78. Given the profile of the local business sector, the Committee would expect that the majority of contracts in NI are awarded to small and micro enterprises. However, as discussed later, it has not been possible to establish comprehensive figures in this regard, including in terms of showing the extent and spread of the indigenous SMEs which are successful in winning government contracts. Nor has it been possible within the timeframe of this Inquiry to undertake a detailed examination of the reasons why some SMEs are successful, while others have either a negative or no experience of the public procurement market. Nonetheless, the Committee sees merit in encouraging new entrants into the procurement market from the small and micro enterprise sector and also in enabling such firms to compete for higher value contracts.

79.The Committee believes that a ‘win-win situation’ will arise from increasing the number of indigenous smaller enterprises competing in the public sector supply chain. For the public sector there is the potential for better value for money, better levels of service and more innovative business solutions. For the smaller enterprises there is the benefit of access to a large and stable market. The Committee also believes that increased participation by indigenous small enterprises in providing services, supplies and works to government in NI could encourage their growth and participation in public procurement markets elsewhere, with the added benefits of boosting employment and of raising the level of productivity/GVA within NI.

80. The Committee notes that, for some years now, the benefits from greater SME access to the public sector supply chain and the barriers to such access have been recognised and documented both locally and internationally. Given the current economic circumstances, the Committee believes that there is now an urgent need for accelerated action in this area. Progress on this front will support the drive for “Competitive Supply", which is included in the twelve guiding principles governing public procurement in NI.

81.In light of the potential benefits, the Committee calls on the Executive to develop a strategic policy for using public procurement, as far as is permitted under the legislation, as a tool for supporting the development of our smaller enterprises and for stimulating economic growth in the longer term. The Committee considers that the implementation of such a policy will require further culture change on the part of government purchasers, which sees a stronger focus on “growing the economy" and creativity in developing procurement solutions which are sensitive to the needs of the economy, whilst also ensuring legal compliance.

Social Economy Enterprises in NI[50]

82. A Social Economy Enterprise (SEE) is defined by DETI as ‘a business that has a social, community or ethical purpose, operates using a commercial business model and has a legal form appropriate to a not-for-personal profit status’.

83. The social economy sector in NI includes a range of organisations such as credit unions, housing associations, local enterprise agencies, community businesses, co-operatives, employee-owned businesses, community development finance initiatives, social entrepreneurs and social firms. Given the relatively low visibility to date and diversity of the sector, no firm, up-to-date, figures are available to quantify its overall size and scale.

84. According to the SEN, the sector in NI is not as well developed as it is in England and Scotland. However a UK-wide survey in 2005 estimated that there were around 600 SEEs in NI, employing in the region of 10,000 people.[51] The Committee welcomes the recent draft of the DETI Social Economy Enterprise Strategy 2010-11, which aims to ensure that the sector is valued, encouraged and supported. [52]