| Homepage > The Work of the Assembly > Committees > Environment > Reports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Volume 1Committee for the EnvironmentReport on the

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Question | Yes / No | ARC21 Response Comments |

| Chapter 2 – | Planning Policy | |

| Question 1 - Do you agree that, in future, Planning Policy Statements should provide strategic direction and regional policy advice only, which would then be interpreted locally in Development Plans? | Yes |

|

| Question 2 - Do you consider there are any elements of operational policy which should be retained in Planning Policy Statements? | Yes |

|

| Chapter 3 – | Towards a More Effective Development Plan System | |

| Question 3 - Do you think it appropriate to commence a ‘plan led’ system in advance of the transfer of the majority of planning functions to district councils under the Review of Public Administration? |

|

|

| Question 4- Do you agree that the objectives contained in paragraph 3.6 are appropriate for local development plans? | Yes |

|

| Question 5 - Do you agree that the functions contained in paragraph 3.7 are appropriate for local development plans? | Yes |

|

| Question 6 - What are your views on the proposal that a district council’s statement of community involvement must be in place before any public consultation on the local development plan? |

|

|

| Question 7 - What are your views on the proposal for a programme management scheme? |

|

|

| Question 8 - Do you agree that a preferred options paper should replace the issues paper? | Yes |

|

| Question 9 - Do you agree with the proposal to introduce a local development plan process that comprises two separate but related documents to be published, examined and adopted separately and in sequence? | Yes |

|

| Question 10 - What are your views on the proposal to deal with amendments to the local development plan? |

|

|

| Question 11 - What are your views on the proposal that representations to a local development plan will be required to demonstrate how their proposed solution complies with robustness tests and makes the plan more robust? |

|

|

| Question 12 - What are your views on the proposal that representations to a local development plan will be required to demonstrate how their proposed solution meets the sustainability objectives of the local development plan? |

|

|

| Question 13 - Should the Department give the examiner(s) the power to determine the most appropriate procedures to be used in dealing with representations to the local development plan? | No |

|

| Question 14 - Do you agree that the representations to the plan should be submitted in full within the statutory consultation period, with no further opportunity to add to, or expand on them, unless requested to do so by the independent examiner | Yes |

|

| Question 15 - What are your views on the proposals for counter representations |

|

|

| Question 16 - Do you agree that the basis for examining plans should be changed from an objection-based approach to one which tests the ‘robustness’ of plans? | Yes |

|

| Question 17 - What are your views on the recommended approach for examining local development plans? |

|

|

| Question 18 - What are your views on the proposals to ensure regular monitoring and review of local development plans? |

|

|

| Question 19 - Do you agree with the proposed content of local development plans as set out in paragraph 3.44? | Yes |

|

| Question 20 -Do you consider that the topic areas contained in paragraph 3.46 are appropriate for inclusion in local development plans? | Yes |

|

| Question 21 -Do you agree that district councils should be required to prepare sustainability appraisals as part of their local plan preparation process? | Yes |

|

| Question 22 - What are your views on the proposal that the Department should have the powers to intervene in the making, alteration or replacement of a local development plan by the district council? |

|

|

| Question 23 a) Do you agree that district councils should be given the power to make joint local development plans if they so wish? b) Do you consider that such powers would adequately deal with instances where neighbouring district councils would consider it beneficial to work together? | Yes |

|

| Question 24- What are your views on the proposed transitional arrangements for development plans? |

|

|

| Chapter 4 – | Creating a Streamlined Development Management System | |

| Question 25 - Do you agree with the proposed introduction of a new planning hierarchy to allow applications for the three proposed categories of development to be processed in proportion to their scale and complexity? | Yes |

|

| Question 26 - Do you agree with the 3 proposed categories of development (regionally significant, major and local) and their respective definitions? | Yes |

|

| Question 27 - In relation to applications for regionally significant development, do you consider that the 4 legislative criteria (see paragraph 4.14), in association with a pre-application screening requirement, are sufficient to identify relevant potential developments? | Yes |

|

| Question 28 - Do you have any comments on the proposed thresholds for the different types of development categories, particularly in relation to the classes of major development described in table 2? |

|

|

| Question 29 - Do you agree with the proposed approach to urban/rural variation in setting the proposed housing thresholds for major development? |

|

|

| Question 30 - Do you agree that performance agreements should be in place before the submission of regionally significant applications? | Yes |

|

| Question 31 - What are your views on the suggested elements contained within a performance agreement, and setting a timescale specific to each individual application? |

|

|

| Question 32 - Do you agree that this should be a voluntary (i.e. non-statutory) agreement? |

|

|

| Question 33 -Do you agree that developers should hold pre-application consultation with the community on regionally significant developments? | Yes |

|

| Question 34 - Do you agree pre-application community consultation should be a statutory requirement? | Yes |

|

| Question 35 - Do you have any views on what the form and process for verifying and reporting the adequacy of pre-application consultation with the community should involve, particularly in relation to the elements indicated above at paragraph 4.32? |

|

|

| Question 36 - Do you agree with introducing the power to decline to determine applications where pre-application community consultation has not been carried out or the applicant has not complied with the requirements of pre-application community consultation? | Yes |

|

| Question 37 - Do you agree that the Department should determine applications for regionally significant development in association with the proposed statutory screening mechanism? | Yes |

|

| Question 38 - Do you agree with the proposal to designate a district council as a statutory consultee where it is affected by an application for regionally significant development? | Yes |

|

| Question 39 - Do you agree with the proposed notification and call-in mechanism, including the pre-application and application stages indicated in diagram 2, for applications for regionally significant development? | Yes |

|

| Question 40 - Do you agree that if the Department decides not to call–in a notified application it should have the option to return the application to the district council, either with or without conditions, for the district council to grant permission subject to conditions that may be specified by the Department? | Yes |

|

| Question 41 - Do you agree with the proposal giving the Department the option to appoint independent examiners to hold a hearing or inquiry into applications for regionally significant development? | No |

|

| Question 42 - Do you agree that the Department should prepare hearing and inquiry procedure rules for use by independent examiners? | No |

|

| Question 43 - Do you agree that the processes for performance agreements should also apply to applications for major development? | No |

|

| Question 44 - Do you agree that the processes for statutory pre-application community consultation should also apply to applications for major development? | Yes |

|

| Question 45 - Do you support a power for district councils to hold pre-determination hearings, with discretion over how they will operate, where they consider it appropriate for major developments? | Yes |

|

| Question 46 - Do you consider that there are other circumstances in which district councils should have the scope to hold such hearings? | Yes |

|

| Question 47 - Where a performance agreement has not been reached, do you consider it appropriate to extend the non-determination appeal timescale for applications for major development to 16 weeks? | Yes |

|

| Question 48 - Do you agree that district councils, post-RPA, shall be required to introduce schemes of officer delegation for local applications? | Yes |

|

| Question 49 - Do you agree that, post-RPA: a) the list of statutory consultees should be extended and b) categories of development, linked to the development hierarchy, that require consultation (including pre-application consultation) before applications are determined by the planning authority, should be introduced? | Yes |

|

| Question 50 - Do you agree, post-RPA, that statutory consultees should be required to respond to the planning authority within a specified timeframe? | Yes |

|

| Question 51 - If so, what do you consider the specified timeframe should be? |

|

|

| Question 52 - Do you agree that the existing legislation should be amended and clarified to ensure that anyone wishing to demolish any part of an unlisted building in a conservation area/ATC/AVC requires conservation area consent or planning permission? | Yes |

|

| Question 53 -Do you agree that the planning authority should be able to require that, where possible, proposed development should enhance the character of a conservation area? | Yes |

|

| Question 54- Do you agree that the normal duration of planning permission and consent should be reduced from five to three years? | Yes |

|

| Question 55 - Do you agree that a statutory provision should be introduced to allow minor amendments to be made to a planning permission? | Yes |

|

| Question 56 - Do you have any comments on the details of such a provision as outlined at 4.101? |

|

|

| Question 57 - Would you be in favour of enabling the planning authority to correct errors in its planning decision documents without the consent of the landowner or applicant? | Yes |

|

| CHAPTER 5 – |

|

|

| Question 58 - Do you agree that the time limit to submit appeals should be reduced? If so, what do you think the time limit should be reduced to – for example, 4, 3 or 2 months? | Yes |

|

| Question 59 -Do you agree: a) that the PAC should be given the powers that would allow it to determine the most appropriate method for processing the appeal; or b) that appellants should be allowed to choose the appeal method? | Yes |

|

| Question 60 - Do you agree that parties to appeals should not be allowed to introduce new material beyond that which was before the planning authority when it made its original decision? | Yes |

|

| Question 61 - Do you agree with the proposal that the planning authority should be able to refuse to consider a planning application where a ‘deemed application’ associated with an appeal against an enforcement notice is pending? | Yes |

|

| Question 62 - Do you agree that the planning authority should have the power to decline repeat applications where, within the last two years, the PAC has refused a similar deemed application? | Yes |

|

| Question 63 - Do you agree that a time limit of 2 months should be introduced for certificate of lawful use or development appeals? | Yes |

|

| Question 64 - Do you agree that the PAC should be given a power to award costs where it is established that one of the parties to an appeal has acted unreasonably and put another party to unnecessary expense? | Yes |

|

| Question 65 - Do you think the new district councils should be able to establish local member review bodies to determine certain local planning appeals? | Yes |

|

| Question 66 - If so, what types of applications should this apply to? |

|

|

| Question 67 - Should provision for third party appeals be an integral part of the NI planning system or not? Please outline the reasons for your support or opposition. | No |

|

| Question 68 - If you do support the introduction of some form of third party appeals, do you think it should an unlimited right of appeal, available to anyone in all circumstances or should it be restricted? |

|

|

| Question 69 - If you think it should be a restricted rights of appeal, to what type of proposals or on what basis/circumstances do you think it should be made available? |

|

|

| Chapter 6 – | Enforcement and Criminalisation | |

| Question 70 - Do you agree that a premium fee should be charged for retrospective planning applications and, if so, what multiple of the normal planning fee do you think it should be? | Yes |

|

| Question 71 - Do you think the Department should consider developing firm proposals for introducing powers similar to those in Scotland, requiring developers to notify the planning authority when they commence development and complete agreed stages? | Yes |

|

| Question 72 - Do you think the Department should consider developing firm proposals for introducing Fixed Penalty Notice powers similar to those in Scotland? | Yes |

|

| Question 73 - Do you think the Department should give further consideration to making it an immediate criminal offence to commence any development without planning permission? | Yes |

|

| Chapter 7 – | Developer Contributions | |

| Question 74 - Do you agree that there is a case for seeking increased contributions from developers in Northern Ireland to support infrastructure provision? | Yes |

|

| Question 75 - If so, should any increase be secured on the basis of extending the use of individual Article 40 agreements with developers on a case by case basis? |

|

|

| Question 76 - Alternatively, should a levy system of financial contributions from developers be investigated in Northern Ireland to supplement existing government funding for general infrastructure needs, e.g. road networks, motorways, water treatment works etc., in addition to the requirements already placed upon developers to mitigate the site-specific impact of their development? |

|

|

| Question 77 - What types of infrastructure should be funded through increased developer contributions, e.g. should affordable housing be included in the definition? |

|

|

| Question 78 - If such a levy system were to be introduced in Northern Ireland should it be on a regional i.e. Northern Ireland-wide, or a sub-regional level? |

|

|

| Question 79 - If such a levy system were to be introduced should all developments be liable to make a financial contribution or only certain types or levels of development e.g. residential, commercial, developments over a certain size? |

|

|

| Chapter 8 – | Enabling Reform | |

| Question 80 - The Department invites views on how we (and other stakeholders) might ensure that all those involved in the planning system have the necessary skills and competencies to effectively use and engage with a reformed planning system. |

|

|

| Question 81 - Post-RPA, do you agree that central government should continue to set planning fees centrally but that this should be reviewed after 3 years and consideration given to transferring fee setting powers to councils? | Yes |

|

| Question 82 - Do you agree that central government should have a statutory planning audit/inspection function covering general or function-specific assessments? | Yes |

|

arc21’s remit is, inter alia, to deliver mission-critical waste infrastructure as set out in its statutory Waste Management Plan. This delivery is critical to the Northern Ireland region in terms of the well-being of the local population, compliance with European legislation, and mitigation of the financial effect of fines for non-compliance.

All of these effects are considered material and it is therefore deemed to be in the public interest to ensure expeditious delivery.

One of the key factors affecting such delivery is securing planning permission for (potentially contentious) waste facilities and it is arc21’s view that the current planning system is not fit for purpose in this regard. Accordingly, we consider that there needs to be radical and progressive change.

The reform proposals are therefore a welcome initiative, but arc21 would seek to make the following comments:

The Reform agenda should not be seen as a “big bang" solution. There is a need for progressive and prompt enhancement of the process to protect the public interest in Northern Ireland.

We have concerns about the formulaic nature of the consultation document which tends to focus responses in ways which could potentially restrict a wider perspective by consultees.

We have concerns that the proposals don’t adequately consider in a joined-up way the strategic context of the post-RPA landscape, particularly around well-being and community planning.

The proposals would benefit from more thinking around implementation, resourcing and transition arrangements. We consider that there are a number of important strands still being considered we would have concerns that the outcome of these will emerge too late to inform the current process. These include issues such as community planning and wellbeing which are the subject of different RPA related work-strands.

As an organisation responsible for the delivery of infrastructure we have a vested interest in a robust performance management regime and agree with it in principle. However, we have concerns around the detailed implementation, particularly in relation to the effect of statutory, community and other consultees to the process and how this could impact on timescale, in the absence of robust control mechanisms.

We have concerns about the extent to which local government has been engaged in a process to date. Given the sector’s remit post RPA, it is critical that this engagement from now on is timely and meaningful.

Ards Borough Council actively engages in the strategic planning process as evidenced by its actions and co-ordination roles in matters such as the Ards and Down Area Plan 2015 and the imminent Public Inquiry into retailing for Newtownards (February 2011).

It acknowledges the clear relationship between spatial planning, community planning and cohesion, and sensitive and sensible development of the natural environment, together with urban and rural communities.

Ards Borough Council is corporately supportive of major reform of the planning process in Northern Ireland and commits to providing strategic input into this reform, as well as to assisting in the delivery of a new planning model for all of Northern Ireland.

It notes the gravity and implications of the Bill’s proposed transfer of function and liability of the majority of the planning function, save for general policy, developments of regional significance, development orders, aspects of the statement of community involvement, of section 72 Orders, of planning zone schemes and particular planning controls.

As such, it vehemently requests that the Planning Bill is developed rather than enabled in view of the fundamental central, local government and inter-agency negotiations that are required in order to construct the necessary time, resources, performance, monitoring and policy issues required to develop a planning function which is efficient, effective, accountable and sustainable.

Ards Borough Council wishes to be a willing partner in the development of the Bill and the emerging planning process but has major concerns in regard to the resourcing and management of the proposals expressed in the Bill. In particular it rejects the punitive measures proposed in the Bill in regard to the Department enforcing as it sees fit a timetable and a community consultation process for local development plans (part 2, pages 3,4 et al) if Council processes are not deemed to be appropriate for such local development plans. “The Council must comply with this direction" is a regularly cited phrase which Ards Borough Council considers inappropriate and inequitable. The content of the Bill, the Council would suggest, is wholly premature in as much that until such times as a substantial and equal partner negotiation takes place in regard to the planning function and the associated transfer of responsibilities, assets and liabilities takes place, the external stakeholder consultation process is largely a bureaucratic, time and money exhausting exercise.

Ards Borough Council approves of a sub regional approach to planning administration linked to a central policy unit for all of Northern Ireland. It supports the role of Councils in regard to being the key agency for delivering and accounting for Local development plans. It wishes to see the integration of community, area and master plans and the associated transfer of resources required from DSD, and the DoE. It does not support the transfer of the local planning function to local authorities until such times as the equal party negotiations referred to above take place, with the requisite transfer of resources and assets and the right as a local authority to deliver a proposed statutory service within local authority performance management standards.

The Council respectfully and firmly requests that its interim response to the Bill is cross referenced by the Committee with the Council’s previous response to the Planning consultations during 2010. This response is attached.

Finally, Ards Borough Council seeks immediate and clear assurances from the Committee and the DoE that the transfer of functions and the associated Bill will not be put into effect until proper and meaningful negotiations occur as mentioned above, in order to ensure a democratic, professional and value for money outcome for ratepayers and the wider public.

Director of Development, On behalf of - Ards Borough Council

January 2011

Armagh City and District Council (the Council) welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Call for Evidence on the Planning Bill. The Council is concerned that such a short turnaround period was given to respond to the consultation which is of paramount importance to the Council and the Local Government Sector as a whole.

There are a number of key strategic issues that will be central to the Council’s ability to deliver an effective planning function when it is transferred to us. These are outlined below.

2.1 There is concern that the Planning Bill is being progressed ahead of the Local Government Reform Policy and Proposals. It would be more appropriate for the two pieces of legislation which specify significant changes in the future delivery of local government to be consulted on at the same time and in conjunction with each other.

2.2 It is considered critical that appropriate accountability and governance arrangements including those currently being consulted on in the local Government Reform Policy and Proposals are in place prior to the transfer of Planning to Councils. It is critical that the following issues are fully thought through, consulted on and implemented prior to the transfer of the function to Councils:

2.3 The Council is concerned that the resources required to deliver the planning function effectively have not been adequately assessed. A full analysis needs to be undertaken to assess the resources required to deliver the development planning, planning control, enforcement and other functions outlined in this bill.

2.4 The funding structure of the planning function needs to be clarified, including a clear breakdown of which planning functions should be covered by planning fees and which functions are currently funded through central government or other means. The burden of the planning function should not be put onto the ratepayers, therefore the Council must be assured that the full resources required to deliver an effective planning service will be transferred to the Council. Of particular concern to the council are the following resource issues:

2.5 Staffing levels. It is well known that due to financial constraints, there has been a transfer of staff out of planning service in recent months and further rationalisation is expected. This has resulted in higher case loads per officer which may have a detrimental impact on service delivery. A detailed analysis of the estimated future case load in all aspects of the planning function is required to ensure that the service is adequately staffed at the time of transfer to local councils, both in terms of numbers of staff and levels of expertise.

2.6 Local Development Planning. The Local Area Plan covering the Armagh City and District Council area is long overdue, as are plans for many other areas in Northern Ireland. The Council welcomes the fact that it will have a role in developing a Local Area Plan and believes that it is right that the local authority should be responsible for this function, however there is great concern that the resources and expertise required to deliver this function will not be available to Councils. In particular the requirements to undertake a survey of the district and to undertake annual monitoring will require additional resources including expertise in Strategic Environmental Assessment and Appropriate Assessment. The Council seeks assurance that an adequate resource to carry out this activity will be transferred to the Council with the function.

2.7 Management Information Systems. Clarity needs to be provided as to the future use of Epic and other IT systems within the planning service. The Council requires clarification as to how this would work and the future investment that may be required to ensure that management information systems are effective.

2.8 Accommodation. Clarification needs to be provided as to the provision of accommodation for the planning function.

2.9 Compensation. There are grave concerns regarding Part 6 of the Bill which outlines the transfer of payment to Councils of compensation relating to the revocation or modification of planning permission. The Council requests that the information is provided on the extent of compensation payments made in the past by the Planning Service or Department. It is critical that funding for this eventuality is also provided by central government so that it does not become a burden on the rate-payers of the District. The Council is particularly concerned that there should be no liability on the Council for retrospective claims on decisions made prior to the transfer of planning to the Council or in the case where claims result from subsequent changes to legislation which is outside of the Council’s control.

2.10 The Council recognises that, as this is a new function transferring to Council, there will be a steep learning curve and therefore some oversight by the Department is to be expected. However, we consider that the oversight provisions laid out in this Bill are extreme. In all aspects of the Bill, the Department has retained the right to intervene in the process whether that be to; call in, monitor, assess, report and/or give directions to Councils in relation to the delivery of this function. There is no right of appeal for the Council should they disagree with a decision of the Department. The Council will seek to develop a productive working relationship with the Department to ensure that the transfer of planning is as seamless as possible and that the subsequent delivery is as effective as possible, however we consider that the level of control and potential intervention by the Department as laid out in the Bill, could be counterproductive and is contrary to local accountability arrangements.

2.11 Planning Policy in Northern Ireland has not kept pace with England, Scotland and Wales. The absence of detailed policy, for example in relation to issues such as pollution and land contamination, makes development control decisions more difficult and time consuming. We would wish to see significant progress in addressing gaps in planning policy, or in the absence of this, guidance for Councils in setting local policies to ensure consistency of approach.

2.12 It is important to ensure that there is sufficient capacity to deliver the planning functions within local government. The capacity issues which need to be addressed include:

| Part 2 – Local Development Plans | ||

| 3 – Survey of District | Details how a Council must keep under review the matters which may be expected to affect the development of the District or the planning of the development. Also that a Council may keep under review and examine matters in relation to any neighbouring district and must consult with the council for the neighbouring district in question. | The Council supports the need for district councils to keep under review matters which are likely to affect the development of its district including matters in any neighbouring district under review. The resource implications need to be fully assessed. The Council will be dependent on a number of government agencies for information and input into the process however, the bill does not detail the mechanism to oblige the relevant government agencies to work with local councils. In addition, the resources to carry out this function adequately need to be assessed and provided for. |

| 4 – Statement of Community Involvement | Council must prepare and agree with Department | The Council welcomes the principle of community involvement as it should result in early efforts being made to address local concerns. However clarification is required as to how the Statement of Community Involvement would work in practice and the impact that this would have on the processing of applications. For the council to do this will require guidance, expertise and resources, especially as in subsection (4) the Department may direct that the statement must be in terms specified and (5) The council must comply. Moreover (6) The Department may prescribe – (a) the procedure…(b) form and content of the statement. Guidance will be required in terms of provision of a process and template that would be acceptable to the Department. |

| 5 – Sustainable Development | Must exercise function with this objective | In subsection (1) the Bill requires that cognisance is taken of contributing to the achievement of sustainable development. Conditions in this regard are specified thereafter, but sustainable development is, in itself, a matter that is capable of various interpretations. Care must be taken that the provisions of this Bill correlate with the sustainable development duty contained within the Northern Ireland (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2006. |

| 6 – Local Development Plan | Development Plan documents are (a) the plan strategy and (b) the local policies plan | The introduction of Local Development Plans is welcomed. The Council notes that there is no mention of the integration of Community Planning with the development of Local Development Plans. It is considered important that these two local planning responsibilities are closely integrated and that environmental and health and wellbeing issues such as Local Air Quality Management, Land Contamination, Obesity Prevention and Physical Activity are considered in Local Development Plans. The Council seeks assurance that an adequate resource to carry out this activity will be transferred to the Council with the function. The Council believes that it is important that appropriate transition arrangements are put in place to facilitate a seamless transition from central to local government? |

| Any determination under this act, regard is to be had to the local development plan, the determination must be made in accordance with the plan unless material considerations indicate otherwise. | ||

| 7 – Timetable | Must be prepared | The procedure to be undertaken between the Council and the Department to agree the terms of the timetable of the Council’s local development plan requires clarification. As the Planning Bill is currently proposed all power rests with the Department to dictate the final terms of the Council’s local development plan. It is noted that the Department has the legislative capacity to disagree with the Council on the timetable and to proceed in requiring the Council to adhere to their direction on the timetable. This role by the department has not been qualified by the Planning Bill. Further clarity on this issue is required and justification for the default role/ power of the Department to direct and control the preparation of the timetable of the Council Local Development Plan. |

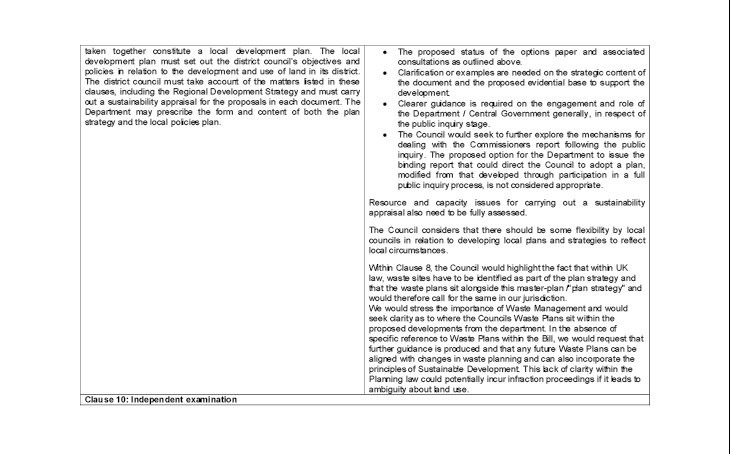

| 8 & 9 – Plan Strategy and Local Policies Plan | Clauses 8 and 9 impose a statutory duty on the district council to prepare a plan strategy and a local policies plan. These documents taken together constitute a local development plan. The local development plan must set out the district council’s objectives and policies in relation to the development and use of land in its district. The district council must take account of the matters listed in these clauses, including the Regional Development Strategy and must carry out a sustainability appraisal for the proposals in each document. The Department may prescribe the form and content of both the plan strategy and the local policies plan. | It is recognised that the preparation of the ‘Plan Strategy’ will be a critical plan making function of the Council and as such clarification is required as to the anticipated form and content of the strategy. Whilst there is reference to this matter at (8(3)) ‘Regulations under this Clause may prescribe the form and content of the plan strategy’, there is no commitment made or timescale suggested for the preparation of such ‘Regulations’. Clarification is required regarding the scope of ‘other matters’ (8(5) (c)) which the Department may prescribe or direct and the required ‘appraisal of the sustainability of the plan strategy’. (8(6)(a)). Clarification is required to the aims and definition of ‘sustainability’ 8 as this can mean different things in different contexts. Resource and capacity issues for carrying out a sustainability appraisal also need to be fully assessed. The Council considers that there should be some flexibility by local councils in relation to developing local plans and strategies to reflect local circumstances. |

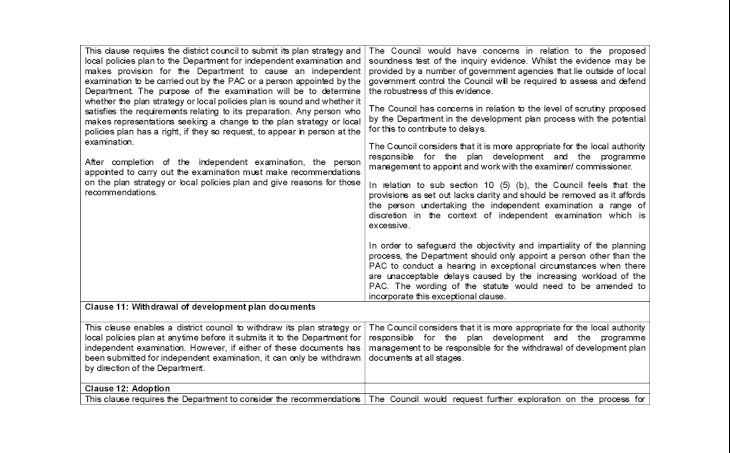

| 10 – Independent Examination | Local Development Plan must be submitted to Dept when ready for examination | There are some concerns as to why the Bill allows for an alternative to the PAC for this function. The Council seeks assurance that the process for appointing such a person will be standard and that the Council will be consulted prior to the appointment of such a person. |

| 11 – Withdrawal | By Council prior to submission to Dept and by Dept after | |

| 12 - Adoption | Dept directs Council to adopt / modify/withdraw the development plan document and give reasons. Council must comply within time period. | |

| 13 - Review of LDP | By Council at such times as Dept may prescribe and report to Dept. | |

| 14 - Revision | Council may revise plan strategy or local policies plan if it thinks it should or Dept directs it to do so. | |

| 15 – Intervention by Department | Before LDP is adopted Dept may direct the Council to modify document | Council seeks a definition of the term ‘unsatisfactory’ in relation to development plan documents as referred to at 15(1) |

| 16 – Department’s Default Powers | If a council is failing or omitting to do anything it is necessary re the preparation or revision of LDP the Dept may prepare or revise the document but must give reasons. The Dept must cause an independent examination to be carried out by the planning appeals commission or a person appointed by the Department. The Council must reimburse Dept for any expenditure in relation to this. | The level of intervention proposed by the Department is extreme. Emphasis should be on a support and assistance on the development plan process. |

| 17 – Joint Plans | Two or more Councils may agree to prepare a joint plan strategy (and joint local policies plan) | The Council welcomes the opportunity to work jointly with other Councils on local development issues and feel that this could be strengthened if the ability to liaise with Councils on a cross-border basis was provided for, as is the case in the Regional Development Strategy. The Council considers that the decision on the joint plan strategy process should be made by the relevant local authorities. |

| 18 – Power of Dept to direct Councils to prepare joint plans | Dept may give direction to do this, councils must comply. | The power that the Department has to give direction in this regard removes autonomy and the decision making powers from local councils on the future development of their local areas. |

| 19 – Exclusion of certain representations | Re new Towns Act 1965, part 7 of the Planning @Order 1991, an order under A14 or 15 of Roads Order 1993, a simplified planning zone scheme or an enterprise zone scheme. | |

| 20 – Guidance | Dept, DRD or OFMDFM guidance must be followed by Council | |

| 21 – Annual Monitoring Report | From each Council to Dept | |

| 22 - Regulations | The Dept may make provision in connection with the exercise by an person of functions under this Part….. | Council requires clear commitment regarding the making of ‘Regulations’ and the detailed requirements therein. The omission of such commitments and any associated timescale undermines the ability of the Council to comment on an informed basis on the provisions of Part 2 of the Planning Bill. |

| Part 3 - Planning Control | ||

| 23 – Meaning of “development" | Means the “carrying out of building, engineering, mining or other operations in, on, over or under land, or the making of any material change in the use of any buildings or other land. Further definitions and exclusions provided. | |

| 24 – Development requiring planning permission | Required for the carrying out of any development of land. | |

| 25 – Hierarchy of Developments | Splits into “Major developments" and “Local Developments". The Department must by regulations describe classes of development and assign each class to one of these categories. Dept may direct a particular local development to be dealt with as major. | Council requires clarification on the types of development that will be assigned as ‘local developments’ and ‘major developments’ and would have preferred that such details would have been available for review at the same time as the legislation is being reviewed. Council is in favour of allowing flexibility in the applications of thresholds in situations where the Department and Council are in agreement. The Council wishes to maintain autonomy over its planning making decision powers insofar as is possible The Council seeks a definition of the term ‘class’ as referred to in 25-(2). The Council seeks clarification as to the provision of 25-(3) where the Department may direct that a ‘local’ development is to be dealt with as if it were a ‘major’ development. |

| 26 – Department’s jurisdiction in relation to developments of regional significance | A person who proposes to apply for permission for any major development (except s209) must…. enter into consultations with the Department. Relates to significance to the whole or substantial part of NI or have significant effects outside NI, or involve a substantial departure from the LDP for area. Must apply for planning permission to Dept. Dept must serve notice on council. Further detail on national security applications, public local inquiries etc. | The Departments definition of what constitutes regional significance must be clearly defined. |

| 27 – Pre-appliciation community consultation | For major developments applicant must give 12 weeks notice to Council before submitting application. Within 21 days the Council may notify the applicant that notice to additional persons is required and that additional consultation is required as specified. | |

| 28 - – Pre-appliciation community consultation Report | Applicant has to prepare report to demonstrate compliance with 27. | |

| 29 – Call in of applications, etc to Department | Dept may give directions requiring applications for pp made to a council or applications for the approval of a council of any matter under a development order, to be referred to it instead of being dealt with by Councils. Further detail provided. | This power afforded to the Department is over and above the legislative measures outlined in Part 3 Clause 25 of the Planning Bill. In the context of the legislative measures already afforded to the Department in the development management process this could be considered excessive. Department needs to outline clearly the criteria which could make an individual application subject to “call in" It would be preferable to ensure the PAC is fully resourced and able to deal with all relevant planning applications, as required. |

| 30 – Pre-determination Hearings | Council to give applicant and any person so prescribed or specified an opportunity of appearing before and being heard by a committee of the council. Procedures for this to be set by council. Right of attendance as considered appropriate by Council. | |

| 31 – Local developments: Schemes of delegation | A Council must prepare a scheme of delegation by which any application for planning permission for a development within the category of local developments …. is determined by a person appointed by the council. Where an application fails to be determined by a person so appointed the council may if it thinks fit, decide to determine an application itself which would otherwise fall to be determined by a person so appointed. | It would be helpful if the Department could set out in guidance a number of process models for the Council to consider in relation to setting up Scheme of Delegation. |

| 32 – Development Orders | The department must by order provide for the grant of planning permission. A development order may either itself grant planning permission for development specified in the order for development of any class so specified or in respect of development for which planning permission is not granted by the order itself, provide for the grant of planning permission by a council. May be made either as a general order to all land, or as a special order applicable only to such land as specified in the order. May be subject to conditions or limitations. May be for use of land on a limited number of days. Further detail provided | Council seeks a detailed definition of ‘development order ‘as referred to at Part 3, Clause 32. |

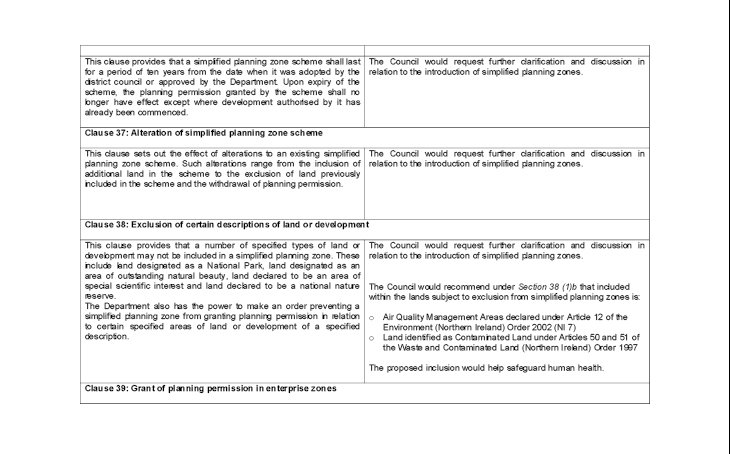

| 33 – 38 - Simplified Planning Zones | SPZ is an area in respect of which a simplified planning zone scheme is in place – has effect to grant planning permission for development specified in the scheme or for development of any class so specified. Council may make or alter within its district. Must take account of Regional development strategy, Departmental policy, guidance etc. Excludes conservation area, national park, areas of outstanding natural beauty, special scientific interest, national nature reserves. | We would request further clarification and discussion in relation to the introduction of simplified planning zones. In principle the planning reform proposal should result in a more effective and speedier planning process which would eliminate the need for simplified planning zones. The granting of Simplified Planning Zones needs careful site-wide consideration prior to their establishment. Much of the development within urban areas will be brownfield development therefore there will need to be express provision to provide the necessary soil investigation reports prior to such designation. We would recommend under Clause 38(1)b that included within the lands subject to exclusion from simplified planning zones is: Air Quality Management Areas declared under Article 12 of the Environment (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 (NI 7) ; Land identified as Contaminated Land under Articles 50 and 51 of the Waste and Contaminated Land (Northern Ireland) Order 1997 (when commenced). The proposed inclusion would help safeguard human health. |

| 39 – Grant of planning permission in enterprise zones | 1981 Order – effect to grant planning permission for development specified. Department may direct that the permission shall not apply in relation to a specified development or specified class of development or a specified class of development in a specified area within the enterprise zone. | |

| Planning Applications | ||

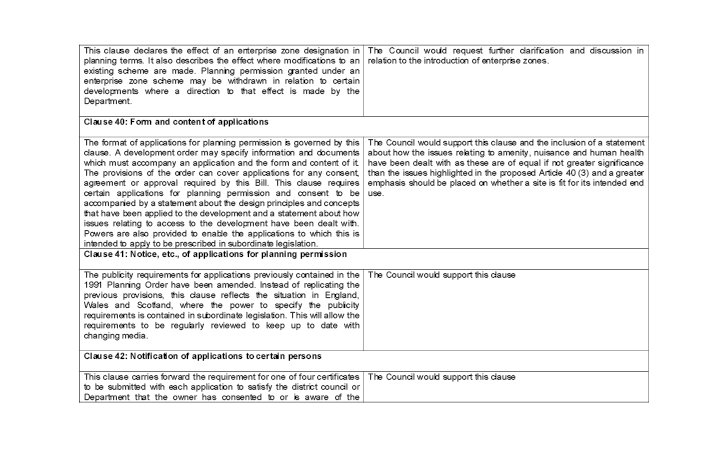

| 40 – Form and Content of applications | The Council requests that consideration be given to introducing more robust Validation Procedures (as is the case in GB) for applications to ensure that only complete applications are accepted, thus speeding up the processing of applications. Consideration should be given to the inclusion of issues relating to amenity, nuisance and human health.as an additional sub-paragraph under 40 (3) | |

| 41 – Notice of applications | ||

| 42 – Notification | Certificates must accompany applications re ownership of land, notice given etc Excludes: NIHE in pursuance of redevelopment scheme approved by DSD or proposed by the Executive; electricity lines; gas pipes; water/sewerage pipes. | |

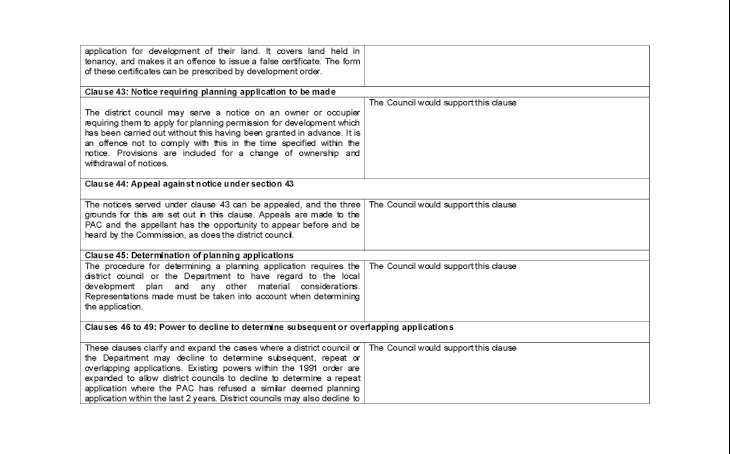

| 43 – Notice requiring planning application to be made | If development already carried out without pp/approval under a development order the Council may issue a notice requiring the making of an application within 28 days. Limit 4 years from development was begun if section 131 or 10 yrs for other development. Offence not to comply with notice, subject to conviction – level 3 daily fines. | |

| 44 – appeal against notice under s 43 | To planning appeals commission | |

| Determination of planning applications | ||

| 45 – Determination of planning applications | Council / Dept must have regard to LDP and to any other material considerations and may grant planning permission, either unconditionally or subject to such conditions as it thinks fit; or may refuse planning permission. A development order may provide that a Council or the Department must not determine an application for planning permission before the end of such period as may be specified by the development order. Council or Dept must take into account any representations relating to that application which are received by it within such period as may be specified by a development order. Must notify those who make representations. | |

| 46 – Power of Council to decline to determine subsequent application | May decline if no significant change since: Within period of two years since similar application refused / conditions is that in that period the planning appeals commission has dismissed an appeal / council has refused more than one similar application and there has been no appeal to pac against such refusal or appeal has been withdrawn. Further instances provided. | |

| 47 – Power of Department to decline to determine subsequent application | Dept may decline to determine an application within 2 yrs of refusal and no significant change, relevant considerations including LDP. | |

| 48 – Power of council to decline to determine overlapping application | May decline if made on same day as similar application or made at a time when any of the conditions applies: similar application under consideration by the Department or PAC under s58/59 Further detail provided. | |

| 49 - Power of Dept to decline to determine overlapping application | Similar to 48 | |

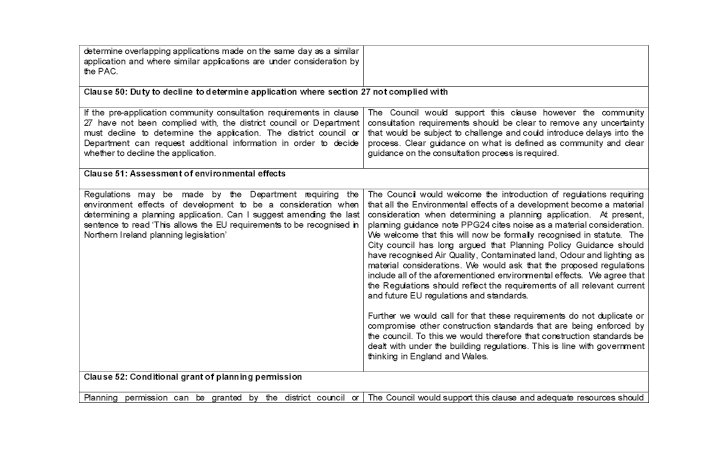

| 50 – Duty to decline where s27 not complied with | Additional information / notice/consultation etc | |

| 51 – Assessment of environmental effects | Dept may by regulations make provision about the consideration to be given to the likely environmental effects of the proposed developments | |

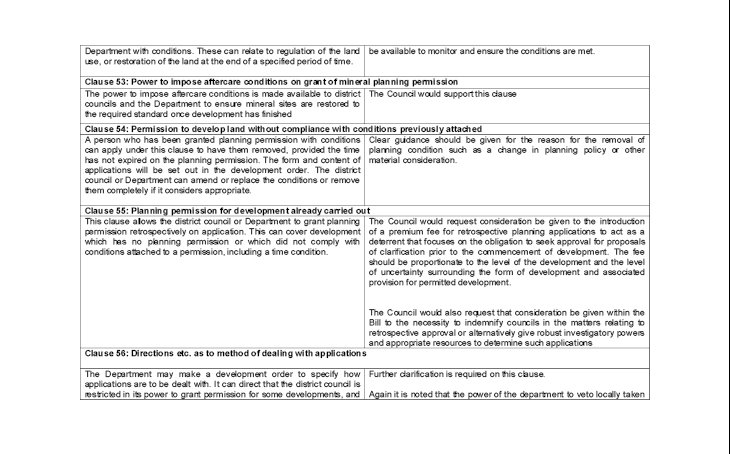

| 52 – Conditional Grant of Planning Permission | Planning permission can be granted by the district council or Department with conditions. These can relate to regulation of the land use, or restoration of the land at the end of a specified period of time. | The Council would support this clause and adequate resources should be available to monitor and ensure the conditions are met. |

| 53 – Power to impose aftercare conditions on grant of mineral planning permission | Conditions requiring site to be restored may be imposed Further detail provided | |

| 54 – Permission to develop land without compliance with conditions previously attached | Applies to applications for the development of land without complying with conditions subject to which a previous planning permission was granted. A development order may make special provision with respect to the form and content of such applications and the procedure to be followed. Details what must be done in order to grant pp in this case. | Clear guidance should be given for the reason for the removal of planning condition such as a change in planning policy or other material consideration. |

| 55- Planning Permission for development already carried out | This clause allows the district council or Department to grant planning permission retrospectively on application. This can cover development which has no planning permission or which did not comply with conditions attached to a permission, including a time condition. | The Council would request consideration be given to the introduction of a premium fee for retrospective planning applications to act as a deterrent that focuses on the obligation to seek approval for proposals of clarification prior to the commencement of development. The fee should be proportionate to the level of the development and the level of uncertainty surrounding the form of development and associated provision for permitted development. The Council would also request that consideration be given within the Bill to the necessity to indemnify councils in the matters relating to retrospective approval or alternatively give robust investigatory powers and appropriate resources to determine such applications |

| 56 – Directions etc as to method of dealing with applications | Provision may be made by a development order for regulating the manner in which applications for planning permission to develop land are to be dealt with by Councils and the Department and in particular (a) for enabling the Department to give directions restricting the grant of planning permission by a council…. (b) For enabling the Department to give directions to a council requiring it to consider imposing a condition or not to grant pp without satisfying the dept that such a condition will be imposed or need not be imposed. (c) For requiring that councils must consult with such authorities or persons as specified by the Order. (d) For requiring the Department to consult with the Council in which the land is situated and others specified. (e) For requiring a Council (or dept) to give any applicant for pp within such time as may be specified such botice as to the manner in which the application has been dealt with. (f) For requiring a Council to give consent agreement or approval required by a condition imposed on a grant within such time as specified. (g) For requiring a council to give to dept and other persons specified such info as may be specified… | |

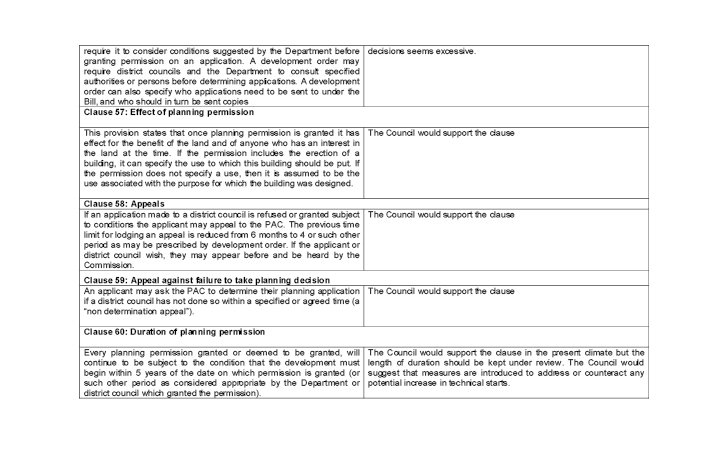

| 57 – Effect of Planning Pemission | Permission shall have effect for the benefit of the land and all persons having an estate therin. Permission for erection of building for purpose specified or if not specified for purpose for which it is designed | |

| 58 - Appeals | Notice in writing to planning appeals commission within 4 months from date of notification of decision. . | |

| 59 – Appeal against failure to take planning decision | If no decision can appeal as if refused | Council seeks clarification on the period (as may be specified by a development order) for determining applications and the responsibility for prescribing the period. |

| 60 – Duration of Planning Permission | Development must be begun within 5 years of date on which permission is granted or such other period as the authority considers appropriate having regard to LDP and other considerations. Exclusions given. | |

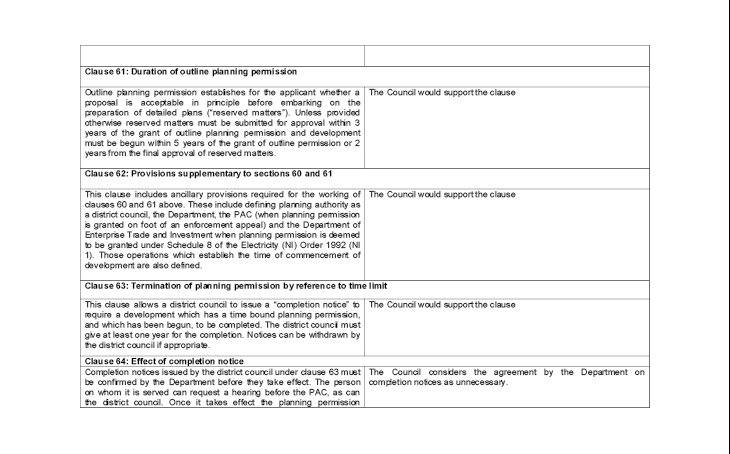

| 61 – Duration of Outline Planning Permission | Application within 3 years in case of reserved matter Development begun by later of 5 years from grant of OPP or 2 yrs from final approval of reserved matters. | |

| 62 - 63 | Further detail on duration / termination due to time limit, including completion notices to be served. | |

| 64 - Effect of Completion notice | Department must confirm and can change details. | |

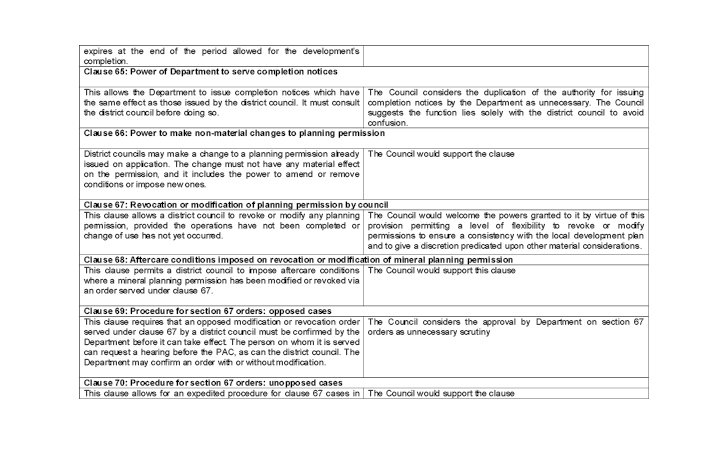

| 65 – Power of Department to serve completion notices | Dept can serve but must consult council. | Council seeks justification as to the provision at 65-(1) for the Department to serve a completion notice itself instead of the Council serving the notice under Clause 64. Council notes that the Department shall consult with the Council if the Department is serving a completion notice; Council seeks clarification as to which authority has the final say on the serving of a completion notice under Clause 65. |

| 66-71 – Changes, revocation or modification of Planning Permission | Details given on when/how this can be done by Council and Department | |

| 72 – Orders requiring discontinuance of use or alteration or removal of buildings or works | If it appears to a council that it is expedient in the interests of the proper planning of an area within its district (including the interests of amenity) regard being had to the local development plan and to any other material considerations that any use of land should be discontinued or that any conditions should be imposed on the continuance of a use of land; or that any buildings or works should be altered or removed; the council may by order require the discontinuance of that use within such time as may be specified in the order, or impose such conditions as may be so specified or require such steps to be taken for the alteration or removal of the buildings or works as the case may be. An order may grant pp for any development of the related land subject to conditions specified… The pp which may be granted under this includes the development carried out before the date on which the order was submitted to the Dept under S73, with effect from date development carried out or end of limited period. Council makes the order. | |

| 73 – Confirmation by Department of S72 Orders | Don’t take effect unless confirmed by the Department. Council must serve notice on the owner and occupier and any other person affected. Must specify time period to give person opportunity to appear before and be heard by pac. | |

| 74 - Power of Dept to make section 72 Orders | Detail given | |

| 75 – Planning Agreements | Any person who has an estate in land may enter into an agreement with the relevant authority facilitating or restricting the development or use of land in any specified way; requiring specified operations or activities to be carried out in, on, under or over the land; requiring the land to be used in any specified way; requiring a sum or sums to be paid to the authority / NI Dept on specified dates; Can be subject to conditions / timescales Dept must consult the Council Further detail given on breaches to planning agreements etc. | Council notes that Council will be the ‘relevant authority’ in relation to all ‘planning agreements’ except those relating to applications where the Council has an estate in the land and those applications made to the Department (the Department must consult with the Council on all planning agreements for development within the Council area). |

| 76 – Modification and discharge of planning agreements | By agreement. Dept must consult council. Person can apply for modification. Relevant authority must determine and give notice of determination within prescribed period. | |

| 77 - Appeals | If relevant authority fails to give notice in 76(8) or determines that a planning agreement shall continue to have effect without modifications the applicant may appeal to PAC. | |

| 78 – Land belonging to councils and development by Councils | Applications to be made to Department. | This is typical of a section where clarification as to the intention and implications of the Bill would be helpful |

| Part 4 – Additional Planning Control | ||

| Chapter 1 Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas | ||

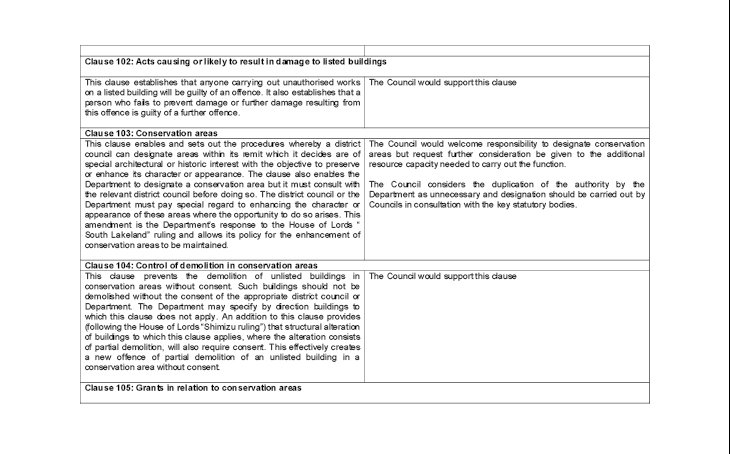

| 79 | Department to compile lists etc | |

| 83 | Council can serve building preservation notices etc on non-listed buildings | The Council welcomes additional measures to protect the built environment but further consideration must be given to the additional resource capacity needed to carry out the function. |

| 84 | This clause provides that carrying out unauthorised works on a listed building will be an offence, and sets out the penalties and the circumstances when works on a listed building may be defended from prosecution. It further establishes when works for demolition, alteration or extension are authorised and excludes ecclesiastical buildings from the workings of this provision. | The fine of £30,000 does not seem a sufficient deterrent to prevent the unauthorised demolition of listed buildings, notwithstanding the possibility of imprisonment for the offence. |

| 85 | Applications to Council for Listed buildings consent | Council seeks clarification of the circumstances whereby an application for listed building consent would be referred to the Department instead of the Council. |

| 88 | Council receives applications but must notify dept. | Clarity on role of Council and Department required |

| 89 – Decision on application for listed building consent | Council role (can be dept depending on circumstances) Can be refused or granted either conditionally or subject to conditions. | Further consideration be given to the additional resource (expertise) capacity needed to carry out the function. |

| 91 – 92 – Power to decline subsequent / overlapping applications | ||

| 103 – Conservation Areas | A council may designate areas of special architectural or historic interest within its district the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance. Dept can also determine areas within council districts. | Council welcomes the provision for Councils to designate areas of special architectural or historic merit (103) but seeks clarification of the circumstances (103(2)) whereby the Department may designate a conservation area. And also requests further consideration be given to the additional resource capacity needed to carry out the function. The council would also welcome further provisions in relation to the enhancement to conservation areas, listed buildings and the like by the introduction of a section similar to Section 215 of the Town and Country Planning Act, England and Wales. This provision would allow the Council to designate protected areas within Armagh City and District Council. Areas such as arterial routes, investment zones and gateways to the city, by appropriate enforcement powers on property owners. |

| 104 – Control of demolition in conservation areas | Council role, or for Council buildings the Dept. | |

| 105 – Grants in relation to conservation area | Dept may make grants or loans for the purpose of preservation or enhancement | |

| 106 – Application of Chapter 1 to land and works of councils | Shall have affect subject to such exceptions and modifications as may be prescribed. | |

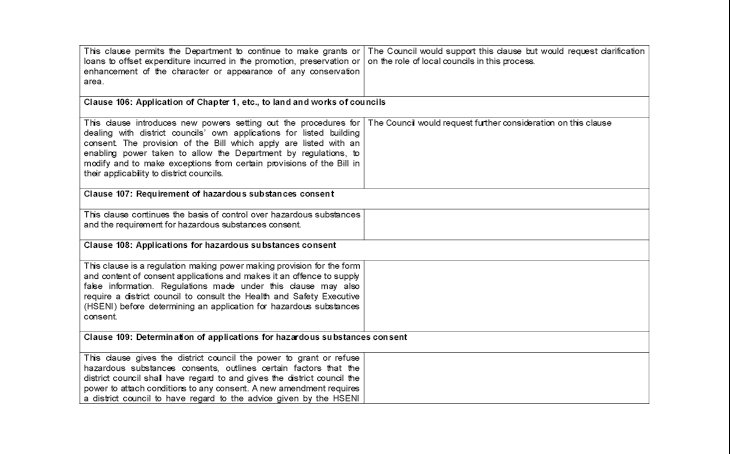

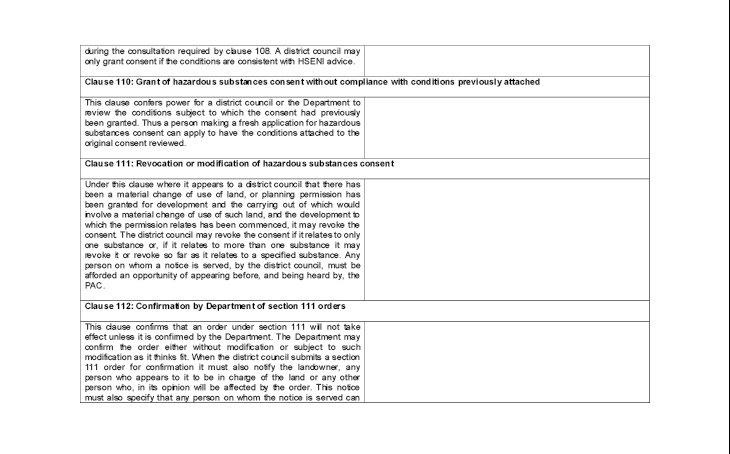

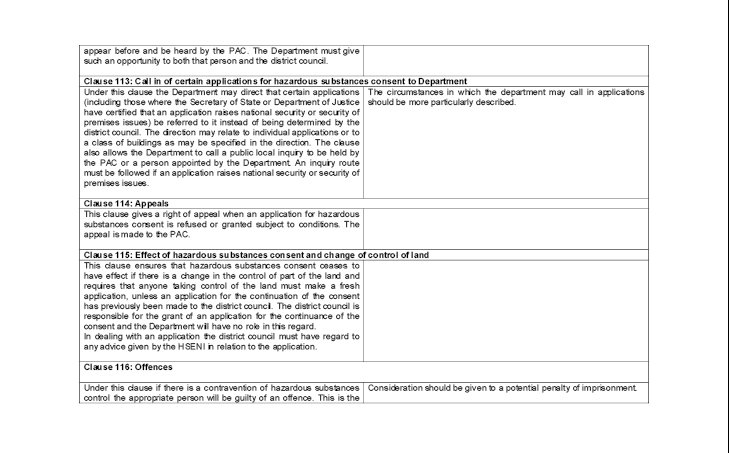

| Chapter 2 Hazardous substances | ||

| Council consent required Dept to specify substances that are hazardous | The Council would welcome the clause but request further consideration be given to the additional resource (specialist Knowledge) capacity needed to carry out the function. | |

| Offences subject to fine up to £30,000 | The fine of £30,000 does not seem a sufficient deterrent | |

| Chapter 3 Trees | ||

| Duty of a council and the department to ensure wherever it is appropriate that in granting planning permission for any development adequate provision is made by the imposition of conditions for the preservation or planting of trees; and make such orders | The Council would welcome the clause but request further consideration be given to the additional resource (specialist Knowledge) capacity needed to carry out the function. | |

| Tree preservation orders – can be made for preservation of trees or woodlands For prohibiting cutting down, topping, lopping, uprooting, wilful damage or wilful destruction of trees except with the consent of council For securing the replanting of woodland which is felled in the course of forestry operations permitted by or under the order | ||

| Chapter 4 Review of Mineral Planning Permissions | ||

| A development order may make provision - mining operations of deposit of mineral waste | This Clause replaces provisions introduced by the Planning Reform (NI) Order 2006. This is anticipated to be a significant new area of work and we believe its implementation has been delayed due to lack of resources. Clarity is sought on how the current centrally held expertise located within Planning Service HQ which deals with most mineral, waste and wind farm applications will be equitably made available to all councils at time of function transfer. It is also noted that the review of mineral planning permissions may introduce compensation liabilities for councils should working rights be restricted. It would be envisaged that as many of the environmental impacts associated with mineral operations are directly related to Environmental Health functions, such a noise and dust control, that considerable resource input would be required on this function. It is not known how many sites are likely to be subject to review, however, it is known that a number of locations across Northern Ireland are likely to require detailed consideration due to the very close proximity of dwellings to mineral operations. The lack of adequate planning guidance in relation to the environmental impacts of mineral operations will make these reviews much more difficult. We would recommend that adequate policy and guidance is developed prior to the commencement of this function. | |

| Chapter 5 Advertisements | ||

| Display, dimensions, appearance, sites etc – consent required from council | ||

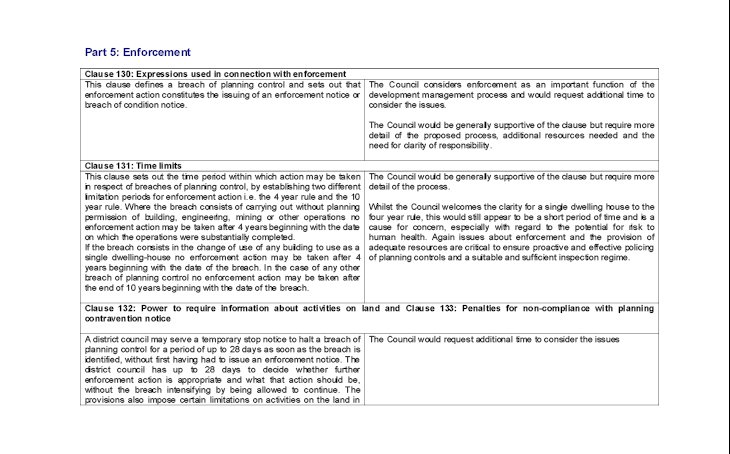

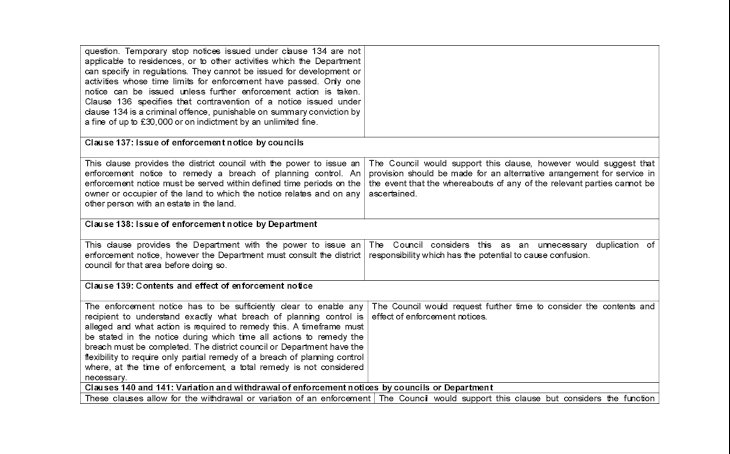

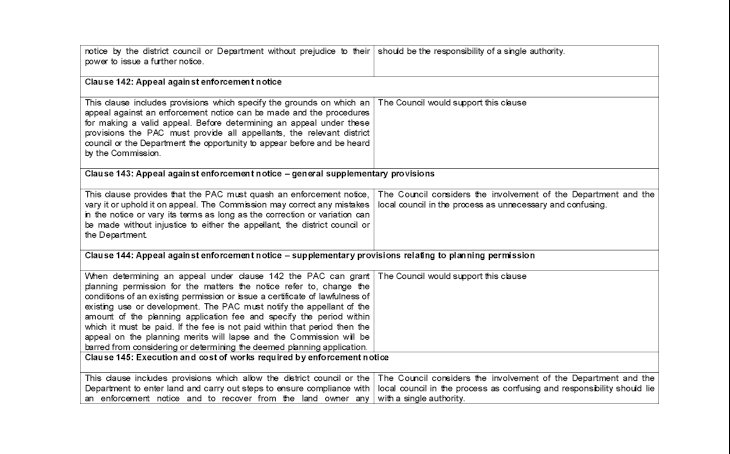

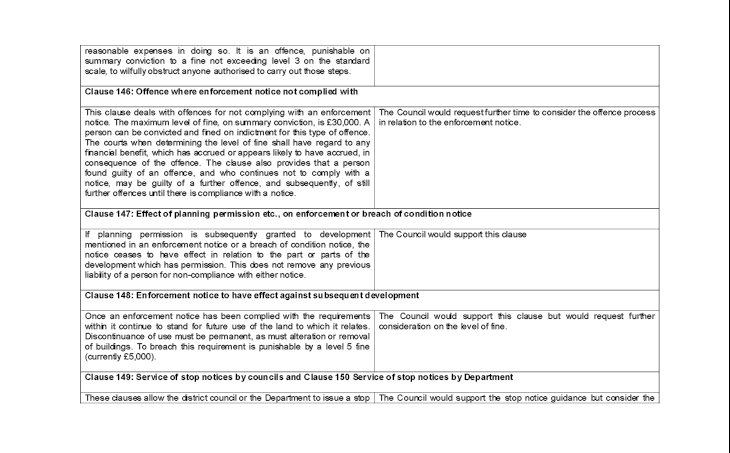

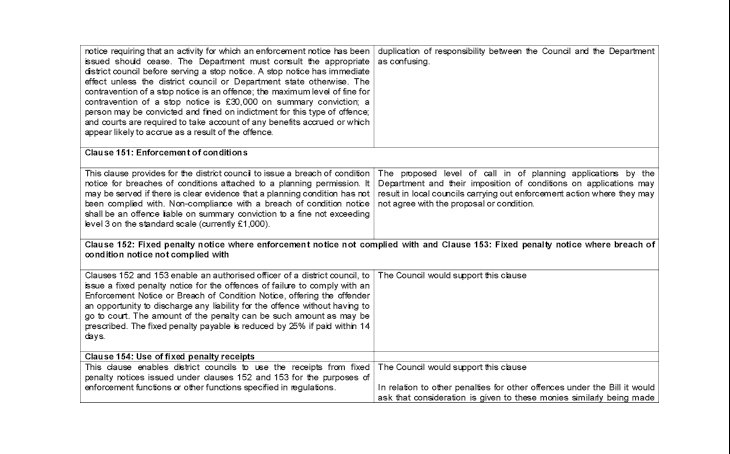

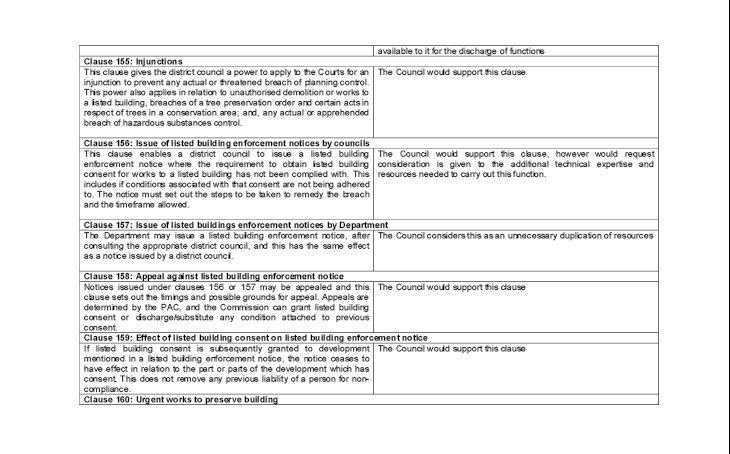

| Part 5 Enforcement | ||

| Clause 130 – 177 | 47 clauses | |

| Includes clauses on the following: | ||

| 131 | Time limits – 4 years for most development | A definition is required for what is meant by ‘substantially complete’ Whilst the Council welcomes the clarity for a single dwelling house to the four year rule, this would still appear to be a short period of time and is a cause for concern, especially with regard to the potential for risk to human health. Again issues about enforcement and the provision of adequate resources are critical to ensure proactive and effective policing of planning controls and a suitable and sufficient inspection regime. It is noted that no provisions have been included which require developers to notify the planning authority on stage completion. We would welcome the introduction of a stage completion requirement as an effective means of ensuring that planning conditions are adhered to within developments. We are aware of the Departments view to evaluate experience in Scotland if similar provisions are commenced. It is recommended that appropriate clauses are included in the primary legislation to accommodate any future decision to introduce this requirement when its value is recognised. |

| 132 | Power to Require information about activities on land | |

| 133 | Penalties for non-compliance with planning contravention notice | |

| 134-136 | Temporary Stop Notices including restrictions and offences | |

| 137-139 | Issue of Enforcement Notices by Councils and Department | |

| 140-144 | Variation / Withdrawal / Appeal of Enforcement Notices | |

| 145 | Execution of works required by enforcement notice and recovery of costs | |

| 149-150 | Service of Stop Notices | |

| 152-153 | Fixed Penalty Notices where enforcement notice not complied with | |

| Use of fixed penalty receipts (council can use for the purposes of htis functions under this part i.e. enforcement) | ||

| 155 | Injunctions | |

| 156-159 | Listed Buildings Enforcement Notices | The Council would support this clause, however would request consideration is given to the additional technical expertise and resources needed to carry out this function. |

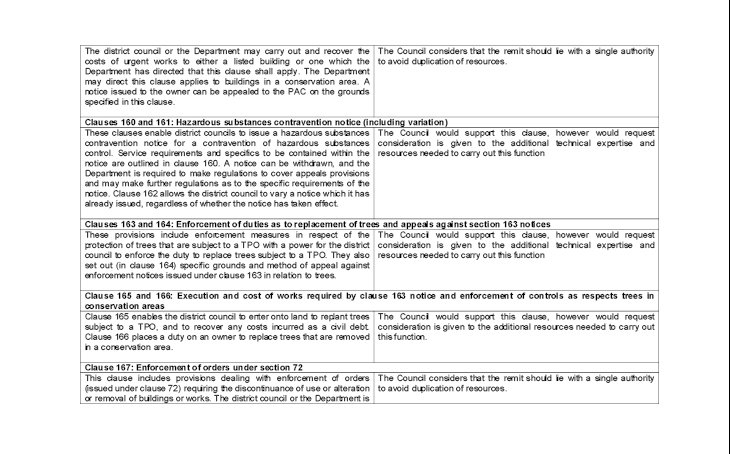

| 160 | Urgent works to preserve building | The Council would support this clause, however would request consideration is given to the additional technical expertise and resources needed to carry out this function |

| 161-162 | Hazardous Substances contravention notices | The Council would support this clause, however would request consideration is given to the additional technical expertise and resources needed to carry out this function |

| 163-166 | Enforcement of duties as to replacement of trees | The Council would support this clause, however would request consideration is given to the additional resources needed to carry out this function. |

| 167 | Discontinuace orders | |

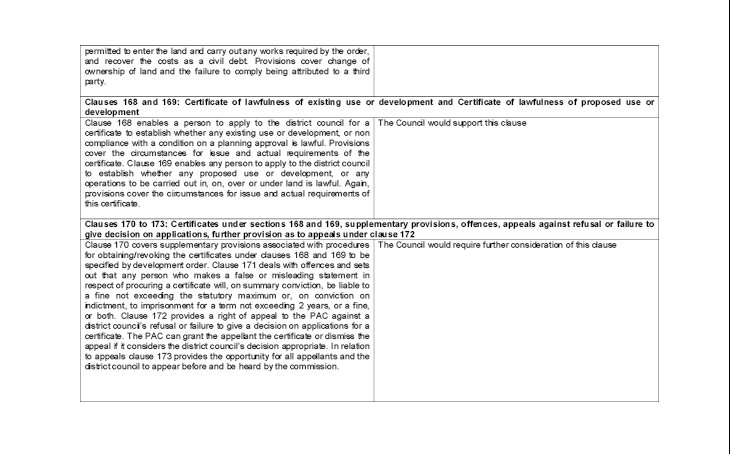

| 168-173 | Certificate of Lawfulness of existing use or development | |

| 174 | Advertisements – enforcement of advertisement control | |

| 175-177 | Right of entry for enforcement | |

| Part 6 Compensation | ||

| Clause 178 -188 | 11 Clauses | |

| Includes clauses on the following: | ||

| 178 | Compensation where planning permission is revoked or modified. The functions exercisable by the Department under the Act of 1965 are hereby transferred to Councils | Council is concerned with the provisions of Clauses 178 – 188 which state that Council must pay compensation associated with a range of circumstances including those in relation to consents which are revoked or modified, and losses due to stop notice and building preservation notices. Council has not been afforded adequate opportunity to consider these provisions which require detailed consideration by the Council’s legal advisors before Council can make a substantive response Councils should be given indications of the potential costs of this measure based on the evidence of Planning Service in its operations |

| 179-188 | Includes compensation relating to minerals, listed building consent, discontinuation of use of land, tree preservation orders, hazardous substances, loss due to stop notices, building preservation notices. | As above |

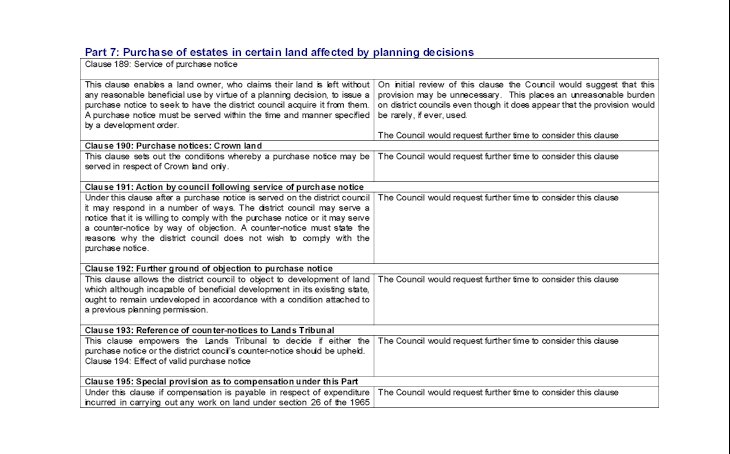

| Part 7 Purchase of Estates in Certain Land Affected by Planning Decisions | ||

| Clause 189 - 195 | 7 clauses | |

| 189 | Where an application for pp is refused or granted subject to conditions and the land owner claims that the land has become incapable of reasonably beneficial use etc, the owner may serve on the council a notice requiring the council to purchase the owners estate in the land. | On initial review of this clause the Council would suggest that this provision may be unnecessary. This places an unreasonable burden on district councils even though it does appear that the provision would be rarely, if ever, used. |

| 191-193 | Actions by Council following service of purchase notice incl objections and referral to lands tribunal | |

| 194 | Effect of valid purchase notice | |

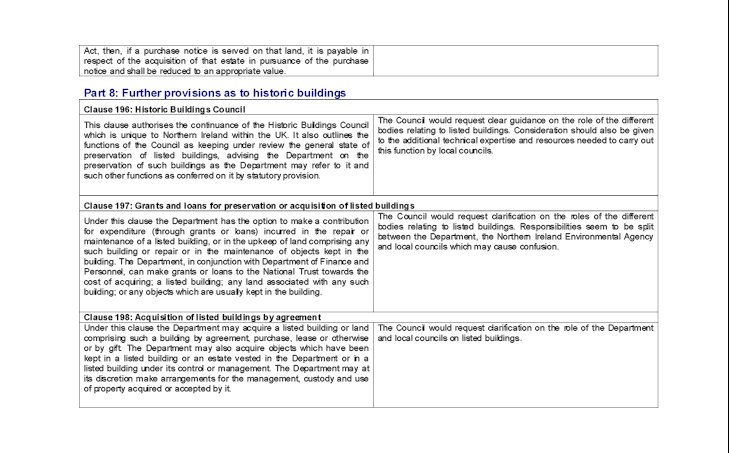

| Part 8 Further Provisions as to Historic Buildings | ||

| Clause 196-200 | Historic Buildings Council will continue to exist | The Council would request clear guidance on the role of the different bodies relating to listed buildings. Consideration should also be given to the additional technical expertise and resources needed to carry out this function by local councils. Responsibilities seem to be split between the Department, the Northern Ireland Environmental Agency and local councils which may cause confusion. |

| Grants and Loans for preservation or acquisition of listed buildings, Endowments of listed buildings, compulsory acquisitions. | ||

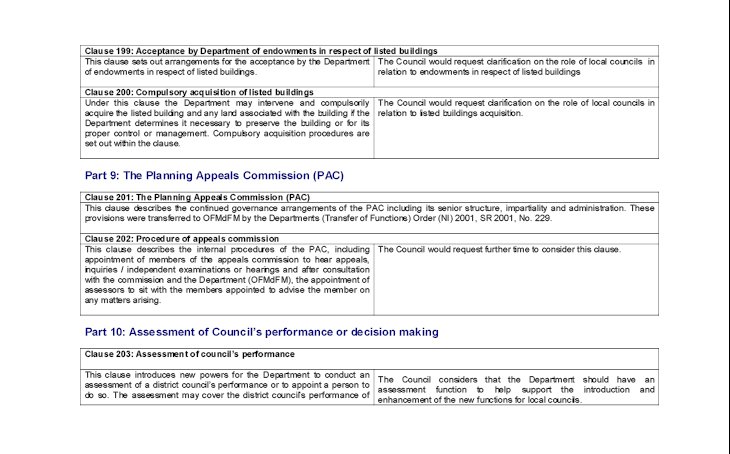

| Part 9 The Planning Appeals Commission | ||

| Clause 201-202 | There shall continue to be a planning appeals commission appointed by FM & DFM | |

| Procedure laid out. | ||

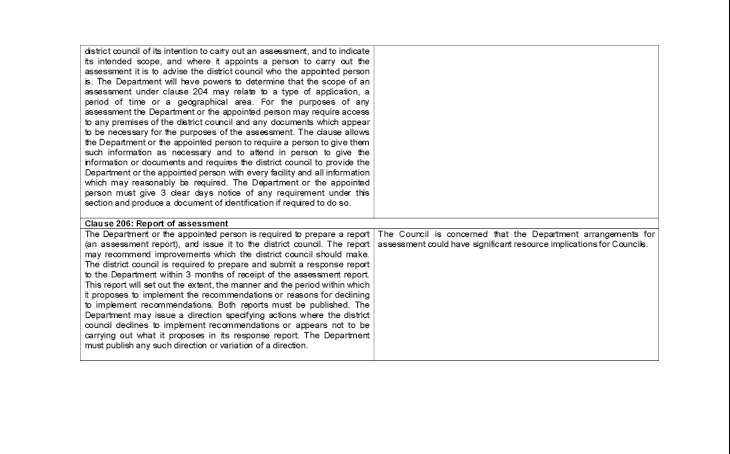

| Part 10 Assessment of Council’s Performance or Decision Making | ||

| Clause 203-206 | This clause introduces new powers for the Department to conduct an assessment of a district council’s performance or to appoint a person to do so. The assessment may cover the district council’s performance of its planning functions in general or of a particular function. | The Council considers that the Department should have an assessment function to help support the introduction and enhancement of the new functions for local councils. The Council would have reservations in relation to the high levels of scrutiny proposed through a number of measures by the bill. The Council considers that the emphasis from the Department should be in providing assistance to local councils in areas of poor performance rather than highlighting poor performance The Council requires clarification on information requirements by the Department for assessment which could have significant resource implications for Councils. The various formal development plan processes and local development management will involve working with external agencies, including the Planning Appeals Commission, which are outside of direct local council responsibility. The Council would suggest that consideration must be given to ensuring their statutory engagement in order to facilitate the effective management and delivery of the local planning process. |

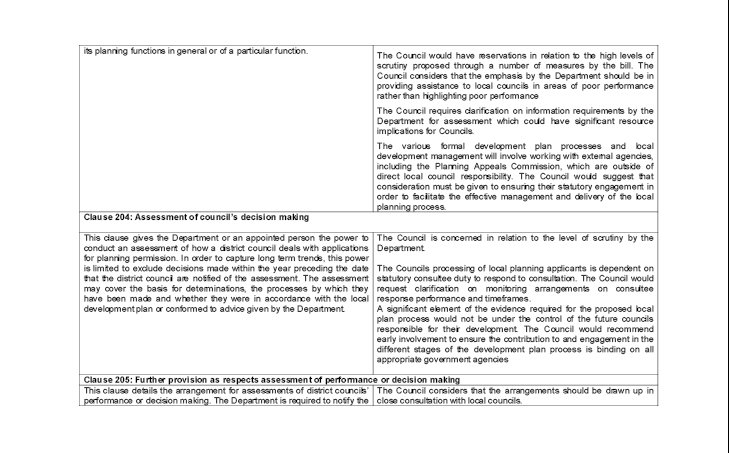

| 203-204 | The Department may conduct or appoint a person to conduct on its behalf an assessment of a council’s performance of its functions under this act or of particular functions. Includes how a council deals with applications for planning permission and in particular as to the basis on which determinations have been made, the processes by which they have been made and whether they have been made in accordance with the local development plan or in conformity with advice given to the council by the Department. | The Council is concerned in relation to the level of scrutiny by the Department. The Councils processing of local planning applicants is dependent on statutory consultee duty to respond to consultation. The Council would request clarification on monitoring arrangements on consultee response performance and timeframes. A significant element of the evidence required for the proposed local plan process would not be under the control of the future councils responsible for their development. The Council would recommend early involvement to ensure the contribution to and engagement in the different stages of the development plan process is binding on all appropriate government agencies Other statutory consultees in the planning process have a key role to play in ensuring the timely delivery of statutory plans and planning application decisions which will ultimately now become a district council responsibility. The Bill could usefully consider the setting of performance standards for these agencies in the form of prescribed response periods which the Department and District Council could jointly monitor and enforce. This would avoid the situation where other consultees set their own pace for responding to a statutory process which the Council will be obliged to deliver timeously and on which we will be assessed. |

| 205-206 | Must notify council and report to council on findings | The Council is concerned that the Department arrangements for assessment could have significant resource implications for Councils. |

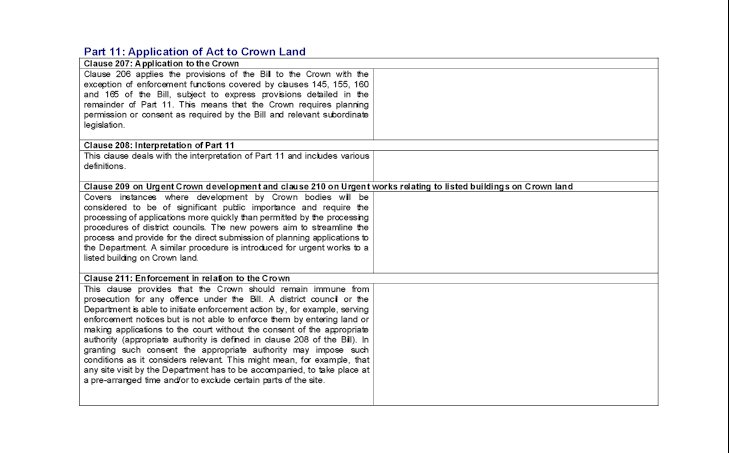

| Part 11 Application of Act to Crown Land | ||

| Clause 207-214 | This Act except s145, 156(6), 160 and 165 binds the Crown to the full extent authorised or permitted by the constitutional laws of NI | |

| Urgent Crown Development – applications to Department | ||

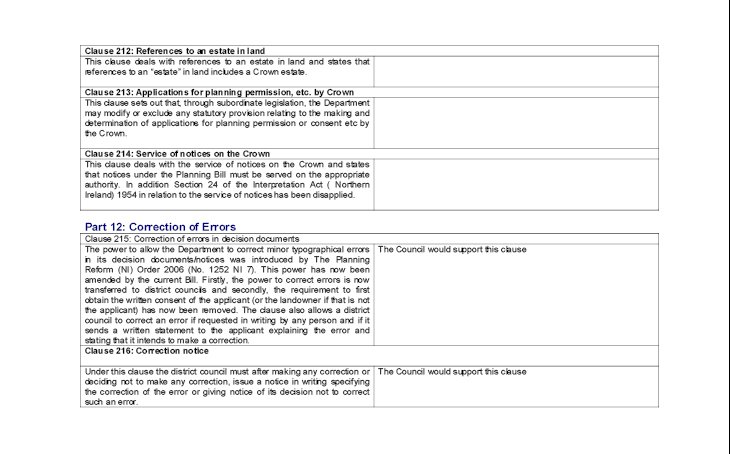

| Part 12 Correction of Errors | ||

| Clause 215-218 | If council or department issues decision document which contains a correctable error they may correct the error in writing. Includes correction notices and effect of correction. | |

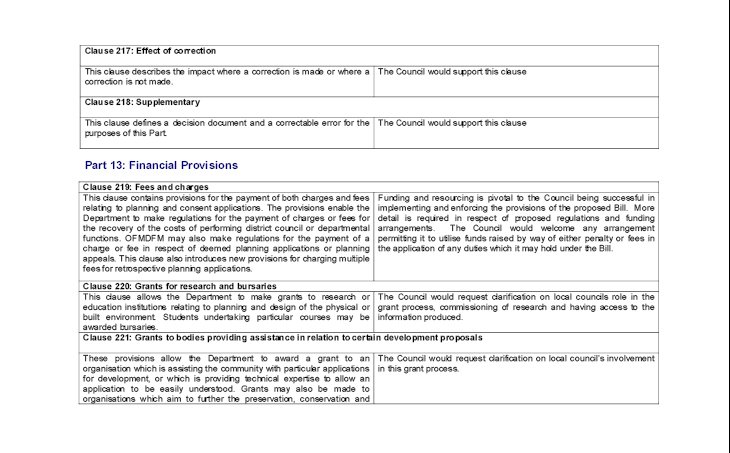

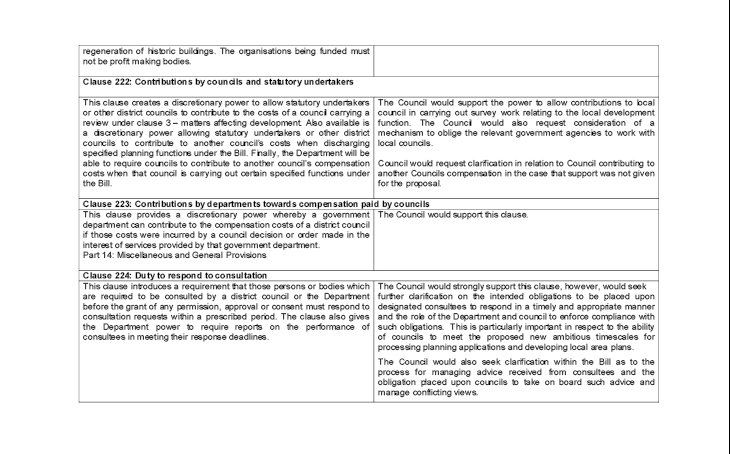

| Part 13 Financial Provisions | ||

| Clause 219 - 223 | The Department may by regulations make such provisions as it thinks fit for the payment of a charge or fee of the prescribed amount in respect of the performance by a council or the Department of any function under this act or anything done calculated to facilitate or is conducive or incidental to the performance of such function. | Funding and resourcing is pivotal to the Council being successful in implementing and enforcing the provisions of the proposed Bill. More detail is required in respect of proposed regulations and funding arrangements. The Council would welcome any arrangement permitting it to utilise funds raised by way of either penalty, fees in the application of any duties which it may hold under the Bill. Should consideration be given to developer contribution as is in the Republic of Ireland? Council seeks clarification on the circumstances whereby Council may be required by the Department to contribute to expenses associated with the functions of another Council. The Council would request consideration of a mechanism to oblige the relevant government agencies to work with local councils. Council would request clarification in relation to Council contributing to another Councils compensation in the case that support was not given for the proposal. |

| Includes grants and bursaries, contributions by councils and statutory undertakers, contributions by departments towards compensation paid by councils. | The Council would request clarification on local council’s involvement in this grant process. | |

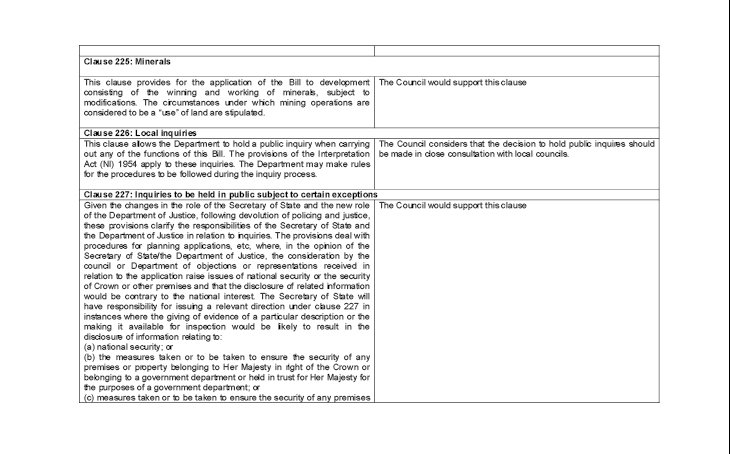

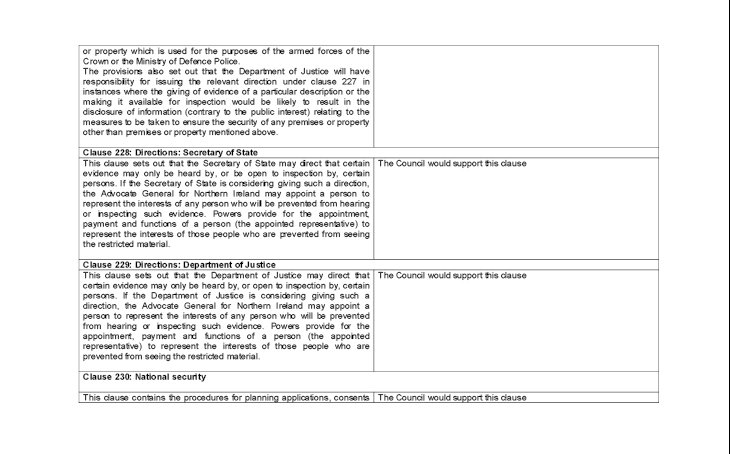

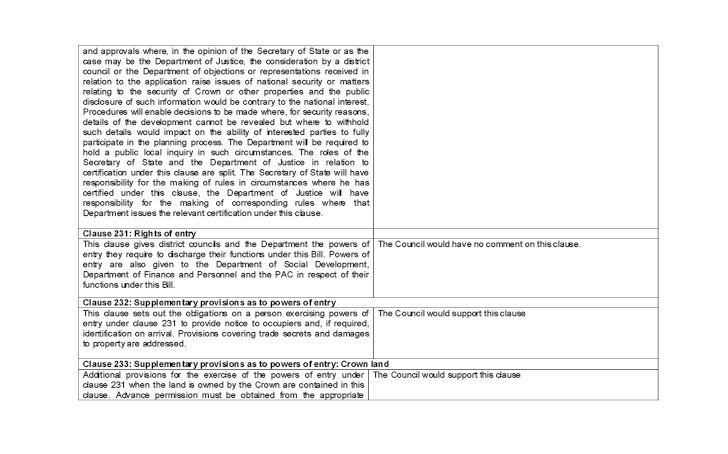

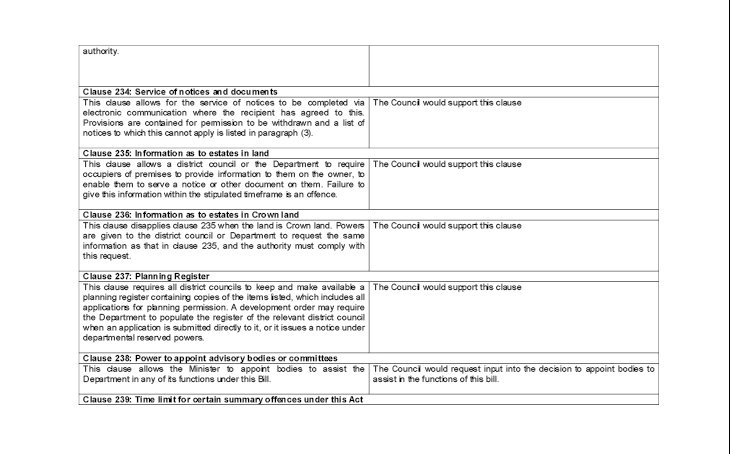

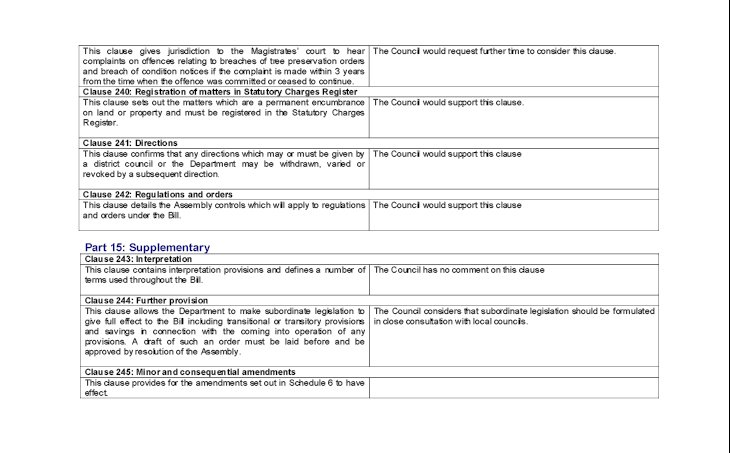

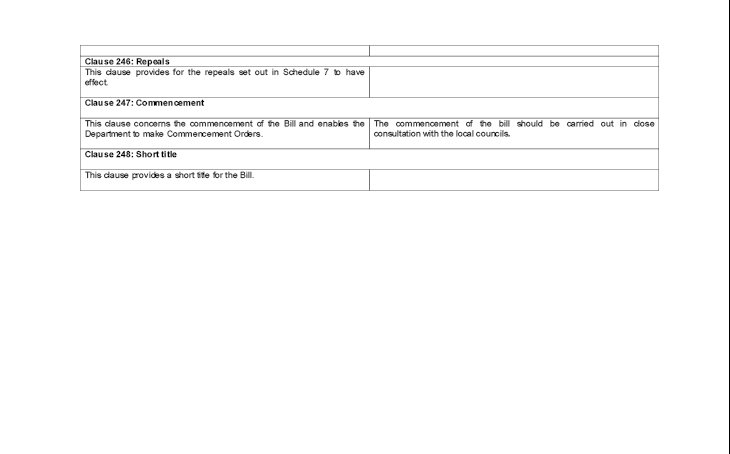

| Part 14 Miscellaneous and General Provisions | ||

| Clause 224-242 | Duty to respond to consultation, minerals, local inquiries, public inquiries, Directions Secretary of State, Directions Department of Justice, National Security, Rights of Entry, Services of Notices and Documents, Information as to estates in land. | The Department may cause a public local inquiry to be held for the purpose of the exercise of any of its functions under the Act. It is not clear who would pay for such an inquiry, and if the costs were to be apportioned, no detail of the various allocations. |

| 237 | Planning Register – Council must keep registers containing listed information | The Council is concerned about the use of the epic system or any other systems required to enable the planning function including the requirements of clause 237 to be met. The Council suggests that the department underwrites potential costs of future development or alterations to the software required. |

Environmental Health comments on the draft Planning Bill

January 2011

Ballymena Borough Council

by the NI Pollution Sub-group. The Environmental Health Department of Ballymena Borough Council wish to endorse the comments of by the NI Pollution Sub-Group for CEHOG in relation to the impacts of draft Planning Bill on the Environmental Health function. Comments are as follows.

It is recognised that many issues regarding the transfer of the development control function to Councils remain to be discussed in detail, not least the resources required to successfully deliver the function. In general terms, however, the principle of a greater role for locally elected members and local government in development control within their area is to be welcomed.

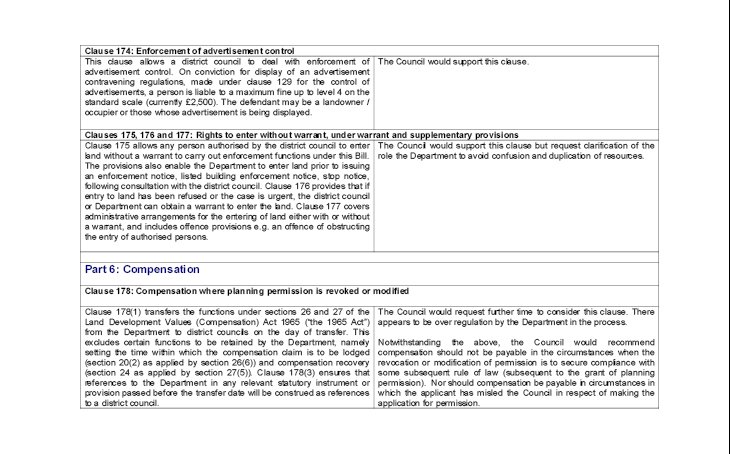

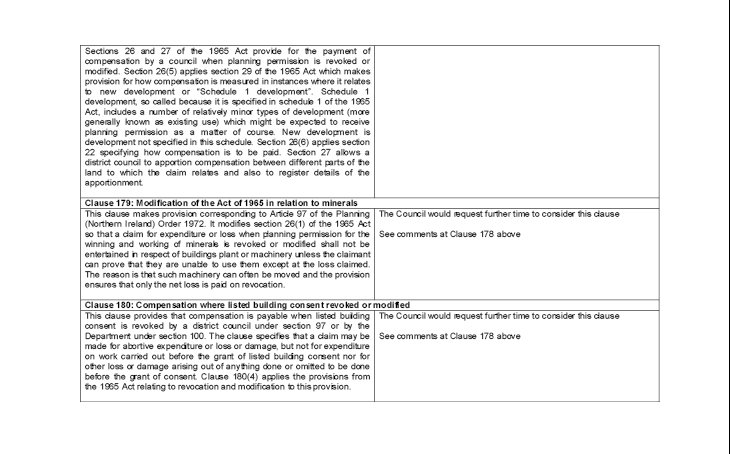

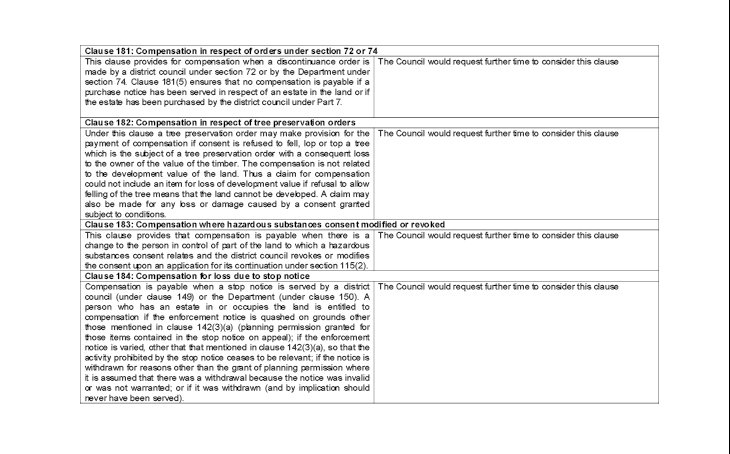

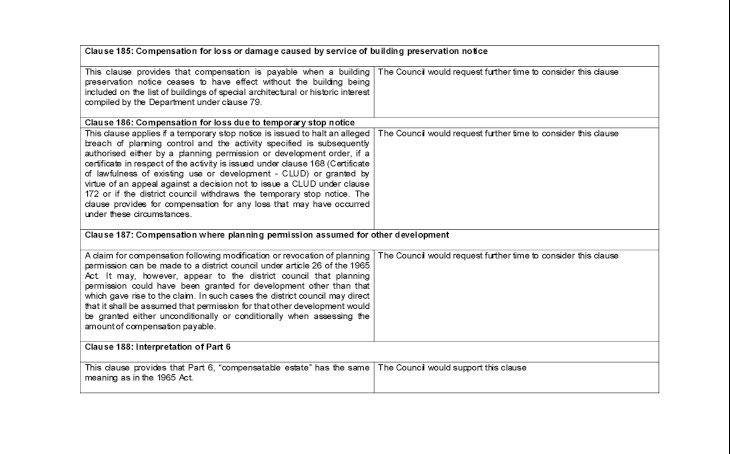

Part 1