| Homepage > The Work of the Assembly > Committees > Employment and Learning > Reports > Report on the Employment (No 2) Bill | ||||||||||||

|

Mr Tom Evans |

Department for Employment and Learning |

1. The Chairperson (Mrs D Kelly): The next item is a briefing from DEL officials on the Employment (No. 2) Bill. This session is being recorded by Hansard. I welcome Tom Evans, employment relations, policy and regulation division; June Ingram, director of strategy and employment relations division; and Alan Scott, whose title I do not have to hand.

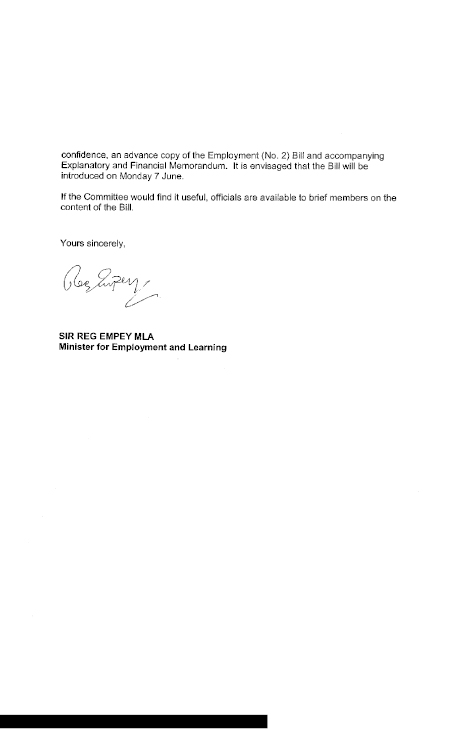

2. The Committee has worked with the Department over the last two years to bring the Bill to this stage. During the pre-legislative scrutiny phase, members already received evidence from a number of key stakeholders. The Committee produced a report of those evidence sessions in June 2009. No amendments to the Bill have been introduced at this stage. I now hand over to the officials for the presentation.

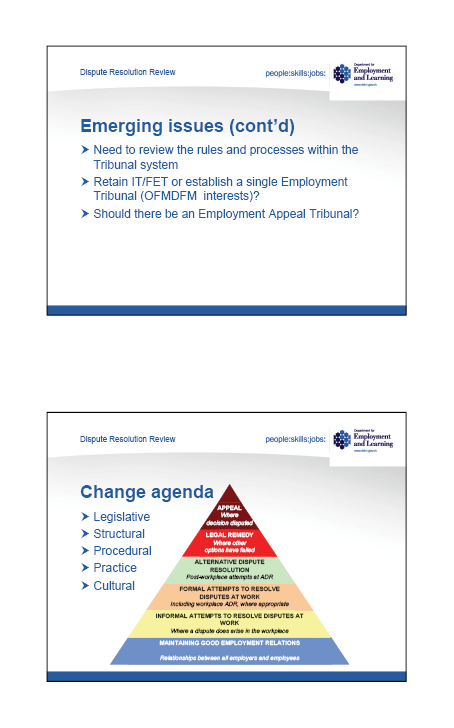

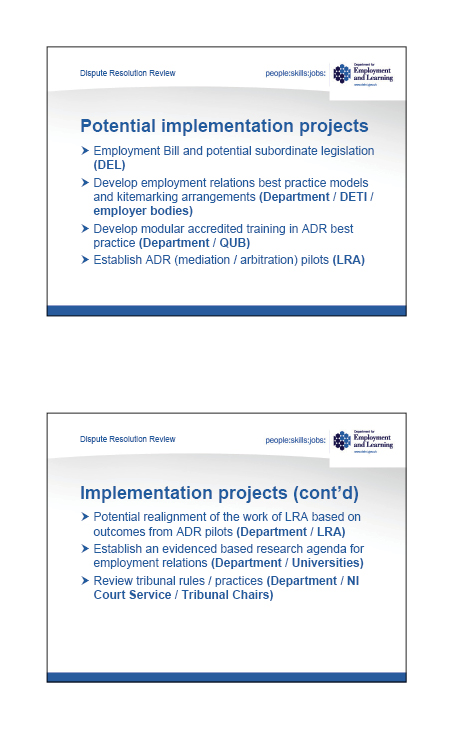

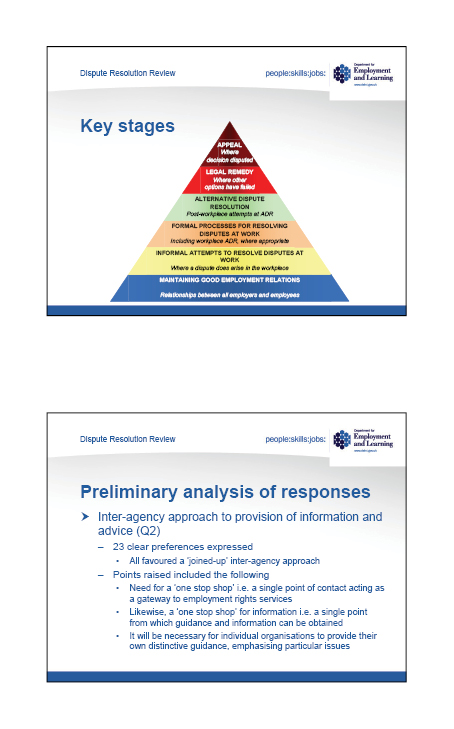

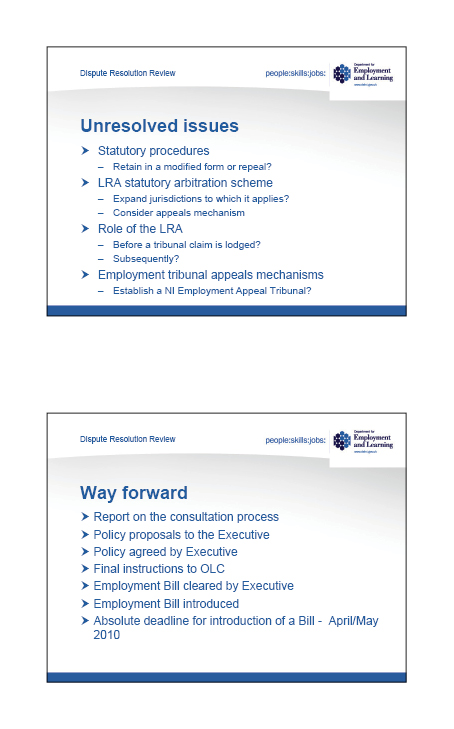

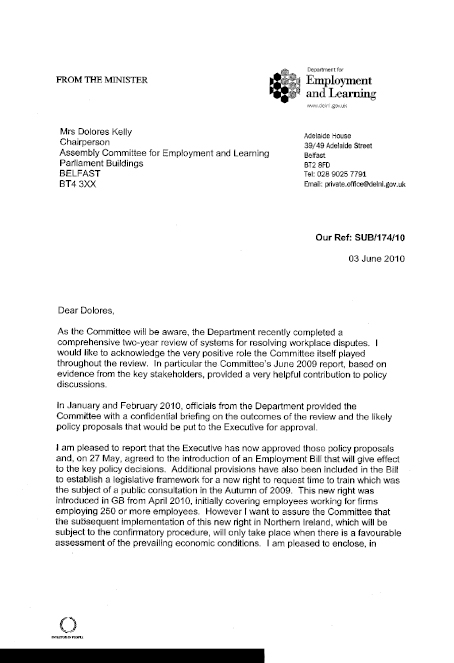

3. Ms June Ingram (Department for Employment and Learning): The Department appreciates the opportunity to present to the Committee the detailed provisions of the Bill. We will explain what it is intended to achieve. It looks to deliver on the policy proposals that were approved by the Executive following the completion of the dispute resolution review. The main provisions will be familiar to the Committee because they largely mirror the policy issues that the Committee surfaced during its consideration of the current arrangements for resolving workplace disputes. I will offer a quick overview of the key areas before a detailed run through the clauses.

4. The Bill is intended to establish a less legalistic framework for raising workplace grievances, while leaving intact a minimum legal standard for disciplinary and dismissal situations. It will repeal the conclusive provisions that link grievance and disciplinary processes to industrial tribunals and fair employment tribunal time limits. It will enable the Labour Relations Agency (LRA) to exercise greater discretion in offering its assistance to resolve disputes, while removing time restrictions for LRA conciliation. It will amend industrial tribunals’ powers to reach a determination without a hearing when the parties consent. It will enable the fair employment tribunal to hear aspects of cases that currently require a separate industrial tribunal hearing; and it will introduce the legislative framework for the right to request time to train.

5. We recognise that the Committee has a strong interest in these policy areas and that it will want to take further evidence from key stakeholders in its consideration of the content of the Bill. We restate our commitment to support the Committee through its stage of the Bill, and we are available to come back to provide further evidence as the Committee wishes.

6. The Bill is substantial; it has 18 clauses and four schedules. I hand over now to Tom Evans to go through the Bill, clause by clause. Alan Scott, who has also been directly involved in drafting, is also here to answer questions as appropriate.

7. Mr Evans (Department for Employment and Learning): As June has said, the Bill has 18 clauses and four schedules, so it has grown during the time that we have been with the Committee. In their papers, members have a copy of the Bill, and they will see an expanded financial memorandum and also a delegated powers memorandum.

8. I will cover the purpose of each clause and highlight areas where the Bill seeks further delegated powers. We have tried to marshal together some of the clauses where they seek to produce the same policy intent or process improvement. I will go through each clause. I am happy for members to ask questions as they arise or at the end, if they find it helpful.

9. The Chairperson: Yes, that would be helpful. For me, the burning question, besides the improved policy frameworks, is whether any cost savings will be realised.

10. Mr Evans: Yes. The first clause concerns the repeal of the statutory grievance procedures. That is a deregulatory measure that amounts to something in the order of £1·5 million immediately. We have been very conscious of the issues around efficiency, effectiveness and any opportunity to reduce. Deregulation by repealing the statutory grievance procedures will have an immediate net benefit to employers.

11. The Chairperson: Given the time that is in it, that is welcome news to all our ears.

12. Mr Evans: I will take clause 1, the repeal of the statutory grievance procedures, and schedule 1 together. I do not need to say much other than that that will repeal the procedures. The current procedures require an employer to put a complaint in writing before bringing it to tribunal. They also require the adjustment of a relevant award where an employee and an employer have unreasonably failed to participate in a subsequent meeting. That is the current three-step procedure.

13. It is clear from the review — the Committee took its own evidence on this — that the statutory grievance procedures were not welcomed. The procedures were well intentioned but problematic and there is universal consensus that they should be removed. Criticism was not levelled at the statutory discipline dismissal procedures and, therefore, the Bill does not propose to repeal those.

14. Clause 2 — statutory dispute resolution procedures and the effect on contracts of employment — repeals article 16 of the Employment (Northern Ireland) Order 2003, which implies in every contract a duty to observe the statutory dispute resolution procedures in circumstances specified by the Department in regulations. The provision that we propose to repeal was never commenced and there is no demand for it. In reality, it has been repealed in GB. If the provision had been commenced, there may have been increased litigation on process as opposed to on how people are being treated, which would have been similar to some of the problems with the statutory grievance procedures. Therefore, the clause proposes to repeal a provision that was never commenced.

15. Clause 3 concerns statutory dispute resolution procedures and the consequential adjustment of time limits. Currently, where parties comply with the statutory dispute resolution procedures, there is provision for automatic extension by three months of the time for lodging a tribunal claim. Clause 3 repeals the relevant powers. I will go back to the previous position, in which employees had a set period of time, usually three months, in which to lodge their claim with a tribunal. A tribunal had the power to continue to accept claims lodged outside that time where it considered that it was not reasonably practical for the claim to have been presented in time, or in certain jurisdictions where it decided that it would be inequitable to allow the claim. The benefit of the change is that it removes a provision that caused confusion. Through the consultation, we saw that people were confused. Clause 3 sets out the time as three months but states that a tribunal will exercise its discretion when it thinks that it is equitable to do so.

16. I will deal with clause 4 — non-compliance with statutory codes of practice — with schedule 2. Clause 4 amends the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to support the non-statutory approach to grievances that will replace the statutory grievance procedures. The changes will establish the context for a revised code of practice that the Labour Relations Agency will produce, setting good practice standards to which employers and employees will be expected to adhere. Failure to comply with the new code would enable a tribunal that considers that inequitable to increase or reduce a relevant award by up to 50%. The Labour Relations Agency, in consultation with us, has already initiated work on a new code of practice and has, in the past few days, released a draft code. That draft code will now go out for a 12-week consultation and we hope that all key stakeholders will input to that. In the UK, there was some criticism of the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service’s (ACAS) draft code of practice. Therefore, we want the Labour Relations Agency’s code to be fit for purpose and for people to be comfortable with it and believe that it is workable.

17. There are delegated powers. The Bill seeks for the Department to be empowered to modify the list of jurisdictions in schedule 4A that would be covered at a tribunal. That is purely to cover the ability to amend those jurisdictions. Employment law is fairly dynamic and, therefore, if we do not have those powers, we will have to come back on the Bill.

18. That takes us to clause 5, which relates to determination of industrial tribunal proceedings without hearing. The clause specifies that the determination of tribunal proceedings without hearing will be permitted only when all parties to the proceedings consent in writing to that process, or when one of the parties presents no response to the proceedings or does not contest the case. That will enable certain simpler cases to be heard on a fast-track basis where parties agree and facts are not disputed. That is really an efficiency measure. It will be for the tribunal to decide how often that will be used. The Bill does not seek additional delegated powers. In fact, the provision restricts the exercise of the existing powers to authorise tribunal proceedings without a hearing. Therefore, parties must consent in writing, not contest the case, or not respond to the claim.

19. That takes us to clause 6, which relates to restriction of publicity. The clause makes it possible for industrial tribunals to restrict publicity in a wider range of circumstances than are presently available to them. Currently, a restricted reporting order may be made in proceedings involving allegations of sexual misconduct. The clause extends the power to cover individuals in relation to whom the disclosure of identifying matter would be likely to cause risk to themselves or their property, and situations in which the tribunal considers such an order to be in the interests of justice.

20. Extended powers to restrict publicity are required so that individuals are not discouraged. That is about encouraging people to participate fully in tribunal proceedings, particularly in areas where sensitive personal information must be disclosed. Recent case law has highlighted the absence of express powers in that area. There is a very general power, the justification of which requires the tribunal to go into significant work. Clause 6 makes it more explicit where the tribunal can restrict publicity in certain cases.

21. In relation to delegated powers, existing regulation powers allowing for the making of a restricted reporting order are expanded to cover the circumstances that we have just set out in new article 13(1A) of the Industrial Tribunals (Northern Ireland) Order 1996.

22. The Chairperson: We know that in fair employment tribunals, for example, there are compromise agreements, which involve a clause of silence or jeopardise the settlement. There is a no blame culture, but it allows organisations to cover up bad practice. How are you going to ensure that this is explicit?

23. Mr Evans: This is not a tribunal proceeding. The compromise agreement is where the case does not progress finally to a tribunal. The compromise agreement is where there has been an agreed settlement between both parties. The reality is that those compromise agreements are confidential, and it would be remiss of the Department to start in any way to interfere with that process. When the Labour Relations Agency is brought in to conciliate a settlement it is done on a confidential basis, but this is very much about the territory of when a case goes to tribunal proceedings. It is about access to justice. It is about not restricting access because somebody is fearful that if they disclose something in tribunal proceedings it may result in some adverse things happening to them as an individual. Some of these phrases are quite lengthy.

24. The Chairperson: The notes are very helpful.

25. Mr Evans: Clause 7 relates to enforcement of sums payable. Again, that is an efficiency measure. At present, where a tribunal orders a party to pay an award and the party fails to do so, a party seeking enforcement through the courts must first register the matter with the County Courts through the enforcement of judgements office. The County Court will then issue an order for enforcement.

26. This clause removes that unnecessary intermediate step. People have been irked by it, and the message — “This is a quick win; please do it" — came right across the table. This is very much an efficiency measure and a process improvement measure.

27. That takes us to clause 8, and I propose to take clause 12 with it. The same policy intent is behind both. Clause 8 deals with industrial tribunals and clause 12 with fair employment tribunals. Clause 8 is about conciliation before the bringing of proceedings. Currently, where parties to a dispute that could result in a tribunal claim seek assistance from the Labour Relations Agency, the agency has a duty to provide that assistance even if there is no prospect of a conciliated settlement. The clause converts the LRA’s duty to a power, enabling the agency to target its resources more efficiently at cases that are more amenable to resolution. The aim is to enhance the agency’s pre-claim conciliation service, a policy that was very much advocated by stakeholders. That has been the direction taken in GB by ACAS, which piloted pre-claim conciliation. The increased emphasis on pre-claim intervention will benefit everyone. It is about earlier resolution and targeting resources. At a time when resources are at a premium, it is important to give the agency that flexibility.

28. Clauses 9 and 13 deal with conciliation after the bringing of proceedings, to either an industrial tribunal or the fair employment tribunal. The Labour Relations Agency has a duty to offer conciliation to parties involved in particular types of industrial tribunal cases, which is currently time-limited to between seven and 13 weeks after a claim has been lodged. More complex cases in both tribunals are not subject to those limits. After the time limit expires in the relevant cases, the LRA is no longer under a duty to offer conciliation, but retains the power to do so. These clauses remove the provisions requiring the LRA’s duty to offer conciliation, and that duty reverts to a power. The original intention of that was to focus the parties’ minds on early resolution, but the review has shown that, in practice, the seven and 13-week time limits were an issue and, to be fair to the Labour Relations Agency, unlike ACAS, it continues to offer a service beyond 13 weeks. We are bringing the legislation into line with the existing practice.

29. We propose to take together clauses 10 and 14, concerning recovery of sums payable under compromises involving the agency. Clause 9 and clause 13 deal with industrial tribunals. This is about compromise agreements relating to cases lodged in both tribunals. The clause has a similar purpose to clause 7, with which I have already dealt. It deals with LRA-brokered settlements of issues that could be determined by tribunals. Where a settlement includes an agreement for one party to pay the other a sum of money, that sum is not paid, and the other party wishes to enforce payment, the clause enables the party seeking payment to pursue the matter through the courts without the need to seek a County Court order for enforcement. Clause 7 is related to that process improvement. The clause applies only in cases where the conciliated settlement simply requires the claimant not to commence tribunal proceedings or where he has begun to end them. Where the conciliated settlement terms are more complex — where, for example, there is a range of conditions — it will not be possible to use that process.

30. The clause removes the paperwork and expenses associated with the current requirement to seek a County Court order for enforcement. Currently, registration of unpaid sums in the County Court carry a small cost so, here again, there will be a small cost saving to the party seeking that enforcement order. The Bill seeks delegated powers whereby the Department may make regulations concerning the time an application may be made to tribunal for a declaration that a compromise sum is not recoverable. Provision is also made by County Court rules on the period during which a sum is not recoverable. This means that either the Department could make regulations on this matter, or the declaration could be made by the County Court. That is to ensure that the provisions are sufficiently comprehensive to cover both situations.

31. Those are very technical issues over which we have laboured to the point that our eyes have sometimes glazed over. However, they are important to improve process, procedure and facilitating administration post the transfer of justice powers.

32. Clause 11 provides powers for fair employment tribunals in relation to matters within the jurisdiction of industrial tribunals. As June Ingram mentioned briefly in her introductory remarks, clause 11 is very much an effectiveness measure in access to justice.

33. Alongside the fair employment aspect of the complaint, the fair employment tribunal currently has the power to hear additional aspects of that claim that relate to other forms of alleged unlawful discrimination where there is a claim of unfair dismissal. Any other aspect of the complaint, such as a claim for unpaid wages or breach of contract must be heard and determined by a separate industrial tribunal. Because all aspects of the claim arise from the same set of facts, it was clear from the consultation that that was seen as an unnecessary duplication and an inefficient way of moving forward.

34. We consulted with the president of the industrial tribunals and the fair employment tribunal, who was encouraged that such an approach would improve the service to the respondents, the employers and claimants — the employees. Therefore, the aim is to amend the existing legislation to remove that anomaly so that the fair employment tribunal and all industrial tribunal aspects of a case can be heard in a single tribunal setting. In reality, many cases in Northern Ireland are not simple; they cover a significant number of jurisdictions.

35. The Chairperson: Is any of this in response to a report stating that the majority of people who put in a claim give up because the process is so elongated, complex and costly that many never get justice?

36. Mr Evans: It was not in response to any particular report or comment from organisations. The Bill is a recognition that, from an employer and an employee’s perspective, the legal system is quite complex. However, in no legal setting other than employment would the same case and set of facts go to two separate tribunals. “No-brainer" is a horrible phrase, but one that jumped out all the time.

37. The Chairperson: Who introduced it to begin with?

38. Mr Bell: Lawyers. [Laughter.]

39. The Chairperson: If it is such a no-brainer, how did it get to be there in the first place?

40. Ms S Ramsey: Civil servants.

41. Mr Evans: The Hansard report may state that there was a pause there. [Laughter.] I think that I have covered that subject enough.

42. That takes us to clause 15, which relates to schedule 3 and deals with the bulk of the Bill’s provisions for dealing with the dispute resolution review. In the debate at Second Stage, we drew the attention of the House and the Committee to the Department’s desire to introduce the right to request time off for training. Clause 15 would amend schedule 3 to enable that.

43. The provisions would allow for the subsequent introduction of a new right for a qualifying employee — somebody with 26 weeks continuous service with their employer — to formally request that their employer give them time away from core duties to undertake study or training. Such an application would have to be for study or training that is intended to improve an employee’s effectiveness at work and the effectiveness of the employer’s business.

44. Under the Bill, employers would be obliged to give serious consideration to such a request and could turn it down only on the basis of one of a specified list of business reasons. That list is comparable to the one that is already provided for in respect of requests for flexible working. The permissible grounds for refusal are listed in schedule 3 of the Employment Rights (Northern Ireland) Order 1996. The provision to request study or training leave is based on those very successful flexible working arrangements.

45. In his address at Second Stage, the Minister gave a commitment that the right would not be introduced until it has been determined that the economic conditions are favourable for such an introduction. The provisions are on the statute book in GB, but, as you mentioned, Chairperson, they are looking at opportunities for deregulation, as are we. We will watch with interest what happens in the rest of the UK.

46. At this stage, it is a right to request time to train, not a right to time to train. It will introduce the powers only. There is no movement, at this stage, to introduce the regulations to commence those powers. The Minister will take a view on that when the economic conditions are right. We will come back to the Committee on that.

47. Ms Lo: It relates to part-time studies. One can say that he or she is going to take a year out to do a master’s degree, for instance.

48. Mr Evans: Yes. It relates to taking time out for training that is relevant to the business and which will improve the employee’s effectiveness and the business’s productivity. There is a range of ways in which people can take training. They can take training through time off, or a part-time Open University degree, for instance. There is a variety of training. There is flexibility on the nature of the training provision, but it is made clear that it must contribute to the employee’s effectiveness, and it must benefit the employer.

49. An individual might say that he or she wants to go away for two years. If that were going to severely impact the effectiveness of the employer’s business in some way, the employer may depend on one of the provisions to turn down such a request.

50. Clause 16 sets out the existing provisions that will be repealed as a consequence of the earlier provisions in the Bill.

51. Clause 17 deals with the commencement of the legislation. It provides for the commencement of the Bill on dates to be specified. We are seeking to try to progress the Bill through its legislative stages so that the provisions will come into effect from April 2011. That would mean that the powers were in place by April 2011.

52. On delegated powers, the Department is empowered to commence the provisions of the Bill on days that it may appoint. We will be working with the Committee to alert it to that, and it is obvious from the debate that we want to commence from April next year.

53. Mrs McGill: I would like some clarification on clause 8, which deals with conciliation before bringing of proceedings. The paragraphs of the explanatory and financial memorandum that deal with clause 8 state that the intention of the amendment is to enable the LRA to prioritise cases where demand for conciliation exceeds available resources. I may have misinterpreted you, but is it the case that if the LRA had sufficient resources, the LRA would proceed?

54. Mr Evans: The intention is to remove the obligation, which is currently required in every circumstance, even when the work that an individual would do would be nugatory and there is no potential for a settlement. Under current legislation, they have to continue to offer that service to anyone who comes along.

55. That is the intention behind it.

56. Mrs McGill: Is that linked with what follows? Are you saying that that is not a reason in itself? Are you saying that where the demand for conciliation exceeds available resources, that is a discrete reason for not continuing?

57. Mr Evans: No.

58. The Chairperson: Are you worried that people will decide not to proceed on the basis of finance?

59. Mrs McGill: I am looking for clarification. Is it because the resources might not be available and the LRA will have difficulties resourcing that kind of service? In my view, that would be a mistake. Is that what it is saying? If so, we need to look at it again.

60. Mr Evans: It is saying that it allows the LRA to target its resources. At the end of the day, all organisations have a finite set of resources, and there is probably an infinite requirement out there. However, regardless of whether 100 people or 20 people approach the agency, there is no added value in providing the service. However, at this stage, there is a duty to do that. The proposal will enable them to take that professional judgement and reallocate their efforts to where they can add value and bring settlements.

61. Mrs McGill: I agree that time should be spent wisely, but I need to ask the same question. Could this happen because the LRA will not be resourced properly?

62. Mr Evans: No. It is purely about giving flexibility to the agency. The agency is probably better placed to say this, but it has a helpline that attracts thousands of callers. Given the economic difficulties at the moment, we understand that the helpline has experienced an increased volume. This is about enabling the LRA to target its resources to best help employees who are in difficulties and employers to resolve differences in a fair and equitable way.

63. Ms Ingram: It gives the agency the flexibility to make decisions.

64. The Chairperson: Yes. However, you can see how others could interpret it.

65. Mr Evans: In real terms, it will increase the potential resource by using resources more effectively. It will reduce potential wastage.

66. The Chairperson: Mrs McGill is saying that it needs to be much clearer that it will be determined by that factor rather than by a financial or resource imperative.

67. Mr Evans: When somebody rings the LRA for help and there is no prospect for it to help, it will not say that it cannot help but will, I imagine, modify the level of service.

68. The Chairperson: The LRA will be before the Committee next week, and we can tease that out further. It is a matter of interpretation, and members seem to want the usage to be explicit rather than implicit.

69. Ms Ingram: It is about ensuring that the right legislative framework is in place. The next stage is how to use that.

70. Ms Lo: That is what I was going to say. Clear criteria need to be set out to enable people to understand under what circumstances the LRA will not take a case forward rather than allowing LRA officers to determine that. People need to know which cases are not likely to be accepted. For example, the Equality Commission now makes it very clear that it will not deal with certain cases, and, as a result, people do not bring those cases.

71. Mr Evans: Yes. As regards LRA, the level of service that it can offer will always be a matter for its professional judgement. That will always be its judgement call. I do not believe that the intention was to set criteria because that in itself would create huge problems. To set criteria acts as a kind of benchmarking exercise. At the end of the day, when people ring up, they may or may not know what they need at that stage. I imagine that professionally trained conciliation and helpline staff is a matter for LRA. We never had any intention to set criteria for that. Perhaps, the explanatory and financial memorandum is not helpful. Our main intention was purely to provide the agency with flexibility to deliver its service.

72. The Chairperson: It did not have to continue to flog a dead horse, to use a country expression.

73. Mr Evans: That is absolutely right, Chair. [Laughter.]

74. The Chairperson: Next week, we can tease out the matter of interpretation further with LRA. I understand where you are coming from. Obviously, people are worried about how it might be interpreted in difficult financial circumstances. We can pick that up with LRA.

75. I believe that that is the end of the presentation. Thank you all very much for coming along. The aim is on target to be met. It is worthwhile. Certainly, a great deal of work has been done in advance to get the Bill to this stage. We do not anticipate a great deal of difficulty apart from those levels of clarification that members require.

76. Mr Evans: Thank you.

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mrs Dolores Kelly (Chairperson)

Mr Jonathan Bell (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Paul Butler

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Chris Lyttle

Mr David McClarty

Mrs Claire McGill

Mr Pat Ramsey

77. The Chairperson (Mrs D Kelly): I know that some members are pushed for time. We plan to informally scrutinise the first two sections of the Bill, which includes the first 10 clauses. The Committee will receive two further briefings on the Bill. This is a preliminary and informal scrutiny of those clauses.

78. The Committee Clerk: I want to stress that this is not the river of no return; it is just an informal look. We will try to get through the first 10 clauses, and we will not go any further. Any Bill is fairly hard to read. Therefore, I am going to give the background to each clause, and members can raise any issues that they may have.

79. The first clause is about the repeal of statutory grievance procedures, and it really does just that. It removes the statutory grievance procedures from statute. The current procedures require an employee to put a complaint in writing before bringing a tribunal complaint. They also require an adjustment of a tribunal award where an employee or employer has unreasonably failed to participate in a subsequent meeting or appeal. The removal of those takes that elaborate and deliberate process out of the way. The whole new focus is to try to bring dispute resolution in the workplace to the local level, where you would try to solve the dispute before you got into the whole written procedures and processes. The first clause removes what is already there so that a new system can be put in place.

80. Clause 2 is another repeal clause. It repeals article 16 of the Employment (Northern Ireland) Order 2003, which implies in every contract of employment a duty to observe the statutory dispute resolution procedures in circumstances specified by the Department. Effectively, we have removed the statutory procedure, and therefore we have to remove the instruction to employers that they have to use the statutory procedure.

81. An awful lot of this Bill is about taking away lots of things in different pieces of primary legislation to achieve something simple and straightforward. Unfortunately, that is part of the problem. A lot of laws and other things have to be dismantled before this law can go forward. Clause 2 takes out the mechanism where employers are forced to use the procedure that is being repealed. If, at any point, this becomes nonsensical, please stop me.

82. The Chairperson: It is fair to comment that trade unions and the employers’ organisations largely support the legislation. It should not be controversial.

83. The Committee Clerk: The Committee did about 18 months’ preparatory work before the Bill even came, and it has had sessions with the various groups and stakeholders.

84. There is currently provision for automatic extension, by three months, of time for lodging a tribunal claim where parties comply with the statutory dispute resolution procedures. Clause 3 repeals that. If we lose the procedures, we have to lose all the instructions to employers that go with those procedures. As I said for clause 2, if the procedures no longer exist, you cannot maintain the laws that are telling employers to enforce them. Again, it is just taking that out of law. The process is very technical and detailed but it needs to be done, otherwise we have random bits of law talking about procedures that no longer exist. It is just another clause that takes out those references from employment law.

85. Clause 4 is relevant to schedule 2. It amends the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992, which supports a non-statutory approach to grievances, replacing the statutory grievance process that the previous three clauses have dismantled and taken away. That change will establish the context for a revised Labour Relations Agency (LRA) code of practice that will set out good practice standards to which employers and employees will be expected to adhere. Failure to comply with the new code will enable a tribunal, if it considers it just and equitable to do so, to increase or reduce a relevant award by up to 50%.

86. Really, all that that is saying is that, now we have taken out the existing grievance procedure, this is what is being put in its place: new relationships and codes with the LRA, and also mechanisms to adjust tribunal awards. Those must be put in place because the Bill will remove the old system.

87. Clause 5 specifies that the determination of tribunal proceedings without a hearing will be permitted only when all parties to the proceedings consent in writing to that process, or when one of the parties presents no response at all in proceedings or does not contest the case. This is really trying to simplify the whole process, so that people are all aware of what is going on and are all saying that, at this point, they are ready to participate in the process.

88. Again, that is needed because we have taken away the old grievance procedure and we need something else in its place that everyone is agreeing to, or, through not specifically agreeing, the kind of tacit agreement. That is what we are saying — if they do not present any response, that is taken as tacit agreement. There is really no way round that. If you perpetually expect a written response from someone that is not going to come, it will delay proceedings for an inordinate amount of time. That has been part of the problem with the existing process. This basically means that everybody gets to the point of saying that they are happy to go with it. You are given a certain amount of time to object to it if you are not happy. If you do not object, then that is it; the process goes ahead. That just tightens everything up and makes it that bit faster.

89. Clause 6 is important. Its provisions make it possible for industrial tribunals to restrict publicity in a wider range of circumstances than at present. Currently, a restricted reporting order may be made in proceedings involving allegations of sexual misconduct. Clause 6 extends that power to cover individuals in relation to whom the disclosure of identifying matter would be likely to cause risk to themselves or their property, and situations where the tribunal considers such an order to be in the interests of justice. It just gives greater flexibility in shielding people whose identification in a tribunal case might make them or their property liable to some kind of attack by way of retribution. This really just offers them greater protection. Previously, the only people in that category were those accused of sexual misconduct. This broadens that out to include a lot of other groups.

90. Clause 7 refers to the enforcement of sums payable from a tribunal. At present, where an industrial tribunal orders a party to pay an award and that party fails to pay the award, a party seeking enforcement through the courts must first register the matter with the County Court through the Enforcement of Judgments Office. The County Court will then issue an order for enforcement. This clause amends that, removing the unnecessary intermediate step. Basically you are going straight to the County Court to enforce of the judgement; you do not have to go through the processes in between. The idea, again, is to make everything neater, tighter and faster. One of the major complaints made in the evidence that we took on the existing procedures is that they take far too long. In taking a long time, enforcement was seen to be ineffective. Clause 7 cuts out the middle part of the process by going straight to the County Court, making the enforcement of judgement, theoretically, that bit faster.

91. Clause 8 — and this also deals with clause 12, but we will be doing clause 12 again at a later date — is to do with conciliation before bringing of proceedings. That is effectively what the whole foundation purpose of the Bill was about — to try to localise dispute resolution, rather than getting into an elaborate process that is going to take a very long time.

92. Currently, where parties to a dispute that could result in a tribunal claim seek assistance from the LRA, the agency has a duty to provide that assistance, even if everybody has flagged up the fact that there is absolutely no prospect of conciliation — for example, if the parties involved are taking other action separately and in parallel to that, and it is totally clear that there will be no conciliation. The LRA is currently still forced to seek some resolution, which will tie up resources and time, when it has been clearly shown to have absolutely no meaning and that it is not going to go anywhere.

93. I know that this was an issue when we heard from the Department. I have had a think about it, and I think part of the issue was that the explanatory memorandum that came with the Bill talked a lot about resources, which perhaps made it appear that this clause was actually saying that the agency will do the cases that it can afford to do. That appeared to be the suggestion. The wording of the Bill itself is more specific, and it actually shows that the agency will prioritise the cases where conciliation is possible. At the moment, it effectively has to do each case in order, whether or not there is going to be conciliation.

94. If you think of it in terms of a list of cases — 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 — and it knows that 2, 4 and 7 are not reconcilable, at the moment the agency still has to deal with 2, 4, and 7. This allows the LRA to not deal with those cases where it has had clear indication that there is no conciliation possible, which means that it is likely to be able to deal with more cases in a shorter space of time, because the cases where there is no resolution are taken out of the equation. Where previously the LRA was forced by the word “must" to deal with each case, they are now using this word “endeavour", so that the LRA will only have to deal with the ones where there is a recognised potential conciliation possible. It is not a question of a cut in resources; that is not what is being flagged up here. It is simply that the LRA is saying that this will make its job more efficient and effective, and it will ultimately be able to deal with more cases that actually have the potential to be resolved. Does that make that clearer?

95. Mrs McGill: As you have outlined is, I have to say that you have done a good job in explaining it, and I understand exactly what you are saying. However, the memorandum is clear in what it is saying. It is my view that what is written there contradicts what you have articulated in many ways. It may well be that the intention is as you have outlined — and I accept that it is — but the memorandum states that:

“The intention of the amendment is to enable the LRA to prioritise cases where demand for conciliation exceeds resources available and to relieve the LRA of the obligation to offer conciliation in pre-tribunal disputes where there is no prospect of success."

96. I am aware that the memorandum is not the Bill, and so on, but, having listened to you, I accept what you have said.

97. The Chairperson: It may be the case that the memorandum could be made more explicit.

98. The Committee Clerk: As Mrs McGill has rightly pointed out, the memorandum is not the law; the Bill is the law. The memorandum is theoretically supposed to unpack the Bill and be useful in terms of supporting and interpreting it. In this case, having spoken to the people who drafted the Bill, it seems that the memorandum has interpreted the Bill in a particular way that gives additional meaning. I suggest that the Committee flag that up in its report, and obviously the Department is here and will be aware that the Committee is concerned about this. We also have the LRA coming, and it might be a useful opportunity to clarify with it how it sees this working.

99. The Bill itself does not indicate that it is an issue of resources, so this may be an occasion on which the memorandum has gone too far in interpreting, beyond what the Bill actually says. I have spoken to officials in the Department, and they suggested that the reading that I have given is the right one and that it is not going to be the case that people will not be heard because of lack of money; it is just the way that that was put. I think they were trying to be helpful by suggesting that dealing faster with cases than can be dealt with will ultimately be a better use of resources. They would understand what we are really saying about that being phrased in a clumsy way in the explanatory and financial memorandum, but it is an issue that we will take up with the LRA when we have it as well.

100. The Chairperson: Obviously the concerns that we have highlighted to the Department in the hope that it will perhaps review the form of words in order to make it much more clear in the memorandum.

101. The Committee Clerk: Clause 9 is to be considered in conjunction with clause 13, which we will come back to at a later stage. It is conciliation after bringing of proceedings. Clause 9 deals specifically with industrial tribunals, which clause 13 mirrors in terms of fair employment tribunals.

102. The LRA has a duty to offer conciliation to parties involved in particular types of industrial tribunal case. It is currently time limited to between seven and 13 weeks after a claim has been lodged. More complicated cases, including industrial tribunal and fair employment tribunal discrimination cases, are not subject to those time limits. In relevant cases, after the time limit expires, the LRA is no longer under a duty to offer conciliation, but it can if it wants. It does retain that power to offer conciliation; it is just that no one is saying that it has to by law. However, I think you know that the operation of the LRA has been that, if its services are required, it will step up to the mark and provide them. Clauses 9 and 13 remove the legislative provisions requiring the LRA to offer conciliation, reverting to a power to do so. Basically, what we are saying there is that there is no longer a case of time limits having expired but the LRA still has to do something. It is now the case that the LRA will go ahead and do the job that it would have done before: if its services are required, it will provide those services. The clauses simply take away that legal obligation where it might not necessarily be required, leaving a power to offer that assistance if people need and want it.

103. Clause 10 is to be thought of in conjunction with clause 14. It has a similar purpose as clause 7. It deals with the LRA-brokered settlement of issues that could or otherwise would be determined by a tribunal. Effectively, it is where the LRA can provide that service and things do not have to go to tribunal. Where a settlement includes an agreement for one party to pay the other a sum of money, but that sum is not paid and the other party wishes to enforce payment — we talked about this before with taking out the middle step and going straight to County Court — the clause enables the party to pursue the matter through the courts, without the need initially to seek a County Court order.

104. Clause 10 applies only to cases in which the conciliated settlement simply requires the claimant not to commence tribunal proceedings or, where they have begun to do so, to end them. Where the conciliated settlement’s terms are more complex, it will not be possible to use this process. That could be described as speeding up the process and making it more direct, so you do not have to go and apply for a County Court order; you can take it straight to the court. That reflects what we heard in clause 7 about speeding up the process and taking out the Enforcement of Judgments Office’s need to go to the County Court in between as a step. This just means that you can basically take it straight to County Court.

105. We will leave those there and come back to this at another time. It is a very technical Bill.

106. The Chairperson: I think that members are content that most of the Bill actually makes sense and that it will help to speed up the process.

107. The Committee Clerk: I stress that a huge amount of consultation went into the Bill. Often, Bills are presented to Committees, but the Committee spent a huge number of months before actually coming to this stage. It has had a lot of thought.

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mrs Dolores Kelly (Chairperson)

Mr Jonathan Bell (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Chris Lyttle

Mrs Claire McGill

Ms Sue Ramsey

Mr Peter Weir

108. The Chairperson (Mrs D Kelly): We move to the continuation of the informal clause-by-clause scrutiny of the Employment (No. 2) Bill. The Committee reached clause 10 in its first session, with issues being raised over clauses 8 and 12. The Labour Relations Agency (LRA) will be briefing the Committee on 10 November, and members have its briefing paper. The paper raises the same issues about clauses 8 and 12 that members are already aware of, along with two further issues. A rewording of the explanatory and financial memorandum with regard to clauses 8 and 12 has been tabled.

109. The Committee Clerk: The first item is a rewording of the parts of the explanatory and financial memorandum that refer to clauses 8 and 12, which members had previously drawn attention to, where it mentions “resources" and so on. I met the lead Bill official last week over this, and the Committee has been offered a rewording of those two parts by the Department. Members may want to have a look at those, take them away and consider them. Effectively they are eliminating any reference to “resources".

110. The LRA will be coming to the Committee on 10 November, but we got its paper in advance so that members could have a look at it. It does raise issues that have been flagged up before. It also supports having discretion to prioritise the caseload that it wants to deal with. That may be a way of the Department then being able to say that it can then lower the LRA’s resources. Obviously, that is a speculative feeling — there has been no statement of that from the Department or anything — but that is what the LRA has suggested could happen. That is contained in the briefing document, and it will come and discuss that with members on 10 November. We wanted to raise it at this point because it has been raised by members before.

111. Those papers are there if members want to take them away and consider them. We have the Law Centre in tomorrow; it has raised different, more abstract issues.

112. To continue with the bits of the Bill and —

113. The Chairperson: As members consider the additional information, they should also bear in mind that some of these measures might actually encourage greater efficiency and effectiveness, as well.

114. The Committee Clerk: The Department has said that essentially the clauses are there to give the LRA the discretion to be able to prioritise cases so that it will not be forced to deal with cases that it knows will not go anywhere or where no conciliation is possible. In the words of the Department, it is a measure for effectiveness and greater efficiency. Members need to balance out those two arguments from the Department and the LRA, and you will have a chance to hear them both on 10 November.

115. As for the Bill itself, as the Chairperson said, we had got as far as clause 10. If I proceed with clause —

116. Mrs McGill: The revised wording of the memorandum — as first glance, I have some difficulty with it. We will be coming back to this: “The intention of the amendment is to relieve the LRA of the obligation to offer conciliation".

117. That does not sit easily with me. It may do with the LRA, but —

118. The Committee Clerk: That is the wording that the Department has offered. I have also come up with my own wording, which I can also offer if it is timely and if members like. It is simpler:

“The intention of the amendment is to enable the LRA to prioritise its cases".

If you stop at the word “cases" and take out:

“where demand for conciliation exceeds resources available",

it will then read:

“The intention of the amendment is to enable the LRA to priorities cases and to relieve the LRA of the obligation to offer conciliation".

That still leaves in the word “relieve", which Mrs McGill has flagged up, but it is a simple possible change. It just eliminates an extra sense without putting anything more in, but it does leave that word “relieve".

119. The Chairperson: It was my understanding that it was to allow the LRA, where there were cases that were going to go to tribunal or to court, that there was not a time-wasting aspect to it. If Mrs McGill wants to bring forward a wording that she might be happy with at a future meeting, that might be useful.

120. Mrs McGill: I think that it is important that it be a Committee decision, in the final analysis.

121. The Chairperson: Oh yes, but if you thought that there is something that would assist —

122. Mrs McGill: I just want to make the point at this initial stage, but thank you.

123. The Chairperson: If any member wants to bring forward a suggested wording, it may well be adopted by the Committee.

124. The Committee Clerk: The Department has shown itself more than happy to look at what alternatives the Committee wants to bring forward, so there should not be any kind of problem.

125. Mrs McGill: We will hear the views of the LRA —

126. The Chairperson: And others.

127. Mrs McGill: And others.

128. The Chairperson: We will indeed. OK, members, we will move to the other clauses. I ask members to stay so that we can get this bit of business done. It will be a couple of minutes.

129. The Committee Clerk: There are only a couple of bits left.

130. Clause 11 covers the powers of the Fair Employment Tribunal in relation to matters within the jurisdiction of industrial tribunals. Members are aware that the Fair Employment Tribunal currently has the power to hear, alongside the fair employment aspect of a complaint, additional aspects of the complaint relating to other forms of alleged unlawful discrimination and unfair dismissal. Any other aspects of the complaint, such as a claim for unpaid wages or breach of contract, must be heard and determined as part of a separate industrial tribunal. It is one case, but if there are these additional elements they have to be heard separately, in an industrial tribunal away from the Fair Employment Tribunal.

131. Since all aspects of the claim often arise out of the same original set of facts, this duplication of effort is considered to be administratively wasteful and an unnecessary burden on all of the parties involved. Clause 11 aims to amend existing legislation to remove that anomaly. It means that all aspects of the case may be heard in one go at the Fair Employment Tribunal at the same proceeding, so there is no need to split it up and have two different cases before two different tribunals.

132. The Chairperson: That should make it easier for claimants.

133. The Committee Clerk: It is a slimming-down, administrative-burden-removal exercise.

134. We skip now to clause 15. Clauses 12 to 14 were dealt with previously when we dealt with earlier clauses where there was a tie-up. Clause 15 works with schedule 3. This is what we can effectively describe as the new element of policy being injected into the Bill. This time off to train or study was not an issue that the Committee originally took evidence on when it did the pre-legislative phase of this Bill. It is a new thing that has been brought to the Bill that the Committee will be thinking about during Committee Stage rather than having thought about previously.

135. The provisions introduce a power that will allow for the subsequent introduction of a new right for a qualifying employee who has had basically half a year’s service — 26 weeks — to make a formal request to the employer for time away from core duties to undertake study or training. The application for this study or training must be to improve the employee’s effectiveness at work and the effectiveness of the employer’s business, so there are criteria within which these applications will have to work.

136. The Chairperson: Mutual.

137. The Committee Clerk: It has to be mutually beneficial. Employers will be obliged to give serious consideration to such a request, and can turn it down only on the basis of one of a specified list of business reasons, comparable to a list that is already in place in respect of the right to request flexible working, which, members will be aware, is in separate legislation. The permissible grounds for refusal are listed as schedule 3, and they will be inserted after article 95 of the Employment Rights (Northern Ireland) Order 1996.

138. The very final thing that we look at is the list of delegated powers. I do not propose to go through them in detail, because it is one of those aspects of the Bill that are extremely technical. However, I will give a broad overview of what delegated powers are for. Essentially, delegated powers are put into other legislation by this Bill to allow the Assembly to have elements of control over future legislation. What we do with the delegated powers is forward them to the Examiner of Statutory Rules, who looks at all the statutory rules for us — that is a protocol that the Committees enter into at the beginning of a mandate. The Examiner of Statutory Rules looks at these to see if they give an appropriate level of delegated power. The Examiner of Statutory Rules has looked at these, and at the parent legislation and so on that they will affect, and he believes these all to be an appropriate level of power and control for the Assembly.

139. Unusually for a Bill that is not a particularly big Bill, there are a lot of delegated powers. If members recall, the last time we did the informal clause-by-clause, I flagged up the fact that this Bill slightly modifies a very large amount of existing primary legislation. That is why there are so many delegated powers.

140. That takes us through to clause 16 and schedule 4, the repeals. That is simply a list of parts of legislation that have to be taken out of other primary legislation because of this Bill. Remember that we talked before about removing the old statutory grievance procedure, and so on. This list simply puts in one place all the bits of legislation that must be repealed.

141. Clause 17 is the commencement clause. All it really does is provide for the commencement of the provisions of the Bill on dates that are specified in Orders made by the Department. That is effectively when things will begin and when everything becomes law.

142. That pretty much takes us through, Chairperson. We have the Law Centre coming tomorrow, and we have received a paper. Next week we have the LRA, as I said before, and the Department immediately after that. It will be giving its views on the same clauses that have been flagged up to us.

143. The Chairperson: Well, members, that was only the informal scrutiny. We will be having formal scrutiny, so if there are concerns that members wish to raise —

144. The Committee Clerk: Previously, I used the phrase “it is not the river of no return". Nothing has been decided.

145. Mr Bell: Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

146. The Chairperson: That is correct. The devil is in the detail.

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mrs Dolores Kelly (Chairperson)

Mr Jonathan Bell (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr Chris Lyttle

Mr David McClarty

Mrs Claire McGill

Mr Pat Ramsey

Ms Sue Ramsey

Witnesses:

Ms Liz Griffith |

Law Centre (NI) |

147. The Chairperson (Mrs D Kelly): I welcome Liz Griffith, policy officer, Karen Mercer, employment adviser, and Daire Murphy, employment adviser. You are all very welcome. Thank you very much for your attendance. The usual format is that witnesses take five to 10 minutes to present their briefing, and members are then given the opportunity to ask questions, to make comments or to seek clarification on any of the points raised.

148. Ms Liz Griffith (Law Centre (NI)): Good morning. Thank you very much for inviting the Law Centre to today’s meeting. I work in policy at the Law Centre. We hope that the Committee is by now well aware of the work that the Law Centre has been doing on this matter. I would like to provide you with the briefest of recaps.

149. The Law Centre has two employment advisers, Karen Mercer and Daire Murphy, who provide specialist advice and representation to claimants. We run a daily advice line and receive advice queries from across the voluntary sector and also from the Labour Relations Agency (LRA), solicitors and constituency offices.

150. We have been very pleased to be able to participate in the Department for Employment and Learning’s (DEL) review of dispute resolution, and we commend the Department for its openness and the approach that it has taken to engagement. We have briefed this Committee twice during the process, and we are pleased that it has maintained a close interest in what has been going on.

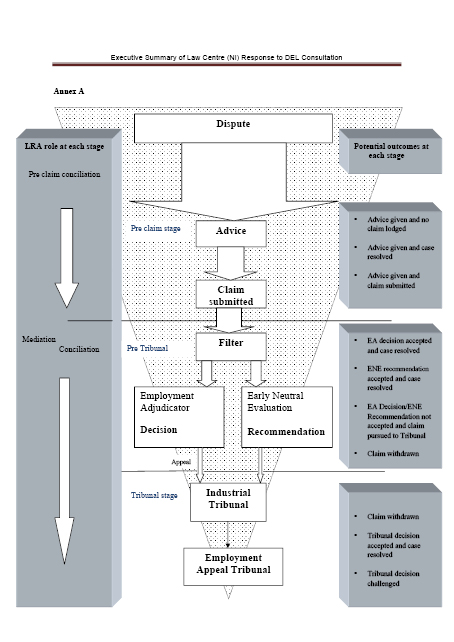

151. Underpinning our involvement in the review is our belief that the current tribunal system contains many major flaws, which means that justice is often inaccessible for claimants. We welcome the Employment (No.2) Bill, but we are anxious to stress that we see it as just one piece of a much bigger jigsaw. We hope that the Committee will play an important role in helping to move towards a systemic reform programme.

152. My colleague Karen Mercer will explain to members why we support a lot of what is in the Bill, after which Daire Murphy will turn to the bigger picture and ask whether the measures in the Bill really mesh together to form a fair and coherent system. Daire will also address the issues that we identified as critical in a briefing paper that I hope the Committee has seen.

153. Finally by way of my introduction, unfortunately, the economic backdrop continues to be sobering. Labour market figures for September showed an increase in the number of claimants receiving unemployment benefits. That reflects our experience at the Law Centre. We have seen an increase in demand for advice, and, specifically, advice relating to dismissals. We noted that a recent report by PricewaterhouseCoopers suggested that up to 36,000 jobs may be lost in Northern Ireland in the coming years. Daire will illustrate what those figures may mean in human terms. We highlight those figures not to be alarmist but to help emphasise that now is a timely moment for reform.

154. Ms Karen Mercer (Law Centre (NI)): Law Centre (NI) welcomes the Employment (No.2) Bill’s repeal of the statutory grievance procedure and its introduction of a code of practice. We congratulate the Committee on finding a Northern Ireland approach to that issue. The grievance procedure has been unduly burdensome and complex for claimants since its inception. It has been a time-consuming and legalistic process that has confused employers, employees and legal representatives. Our experience is that it has acted as a bar on access to justice for claimants.

155. The problems were that claimants were potentially ignorant of the procedure or baffled by its complexity, and that resulted in claims being made at an early stage, which had the impact of preventing claims — even meritorious ones — going forward. The grievance procedure led to formality and legal escalation at the start of the process, which lessened the opportunity for internal resolution. Therefore, we welcome the introduction of a code that is more accessible and less onerous for employers and employees. We hope that that, in turn, encourages greater use of less formal resolution options.

156. We are also pleased to see that the Bill retains the disciplinary and dismissal procedures. Those are established procedures with which employers are familiar. We believe that the three-step process is well-known by employers and is not particularly onerous for them. It offers clarity to employer and employee, in contrast to the grievance procedure, and is relatively simple and straightforward to operate. It assists employees by offering a guarantee of basic procedural fairness when a sanction such as dismissal is being considered. Given the serious consequences of dismissal, we think that it is a reasonable option to ensure that the decision to dismiss should not be taken lightly. The retention of those procedures means that employees in Northern Ireland will continue to enjoy the protection of that unequivocal, statutory right.

157. Our casework contains numerous examples of the importance of the statutory disciplinary and dismissal procedures. Recently, we argued for an employee for whom the dismissal procedure was not followed. That particular employee had been selected for redundancy despite his having the longest service history in the company and a wider range of skills than most other employees. No meeting was held in the company, which did not afford the employee the opportunity to input to the process. As the statutory dismissal procedure had not been followed and the employer had not shown the employee any selection criteria, it was automatically unfair. Had the procedure been followed, the employee would have had the opportunity to input to the process and to challenge his selection for redundancy, and, ultimately, he would not have been dismissed.

158. Cases such as that highlight the importance of the procedures. They are necessary and vital if any level of fairness is to be achieved. They allow the employee to input to a decision that will potentially have a serious consequence for them, to defend their position and, ultimately, to avoid a potential dismissal. Retention of those procedures avoids dismissals that are based on incomplete or incorrect facts, and it also reduces the possibility of unfair dismissal claims against employers.

159. We also welcome the change to the enforcement of sums payable. We believe that the removal of the requirement to seek a County Court order will simplify the process. Currently, the process is lengthy and costly for claimants. It places the burden on the claimants, which, in turn, effectively erodes confidence in the system. By the time that a claimant reaches the end of the tribunal process and is faced with having to pursue their award, a lot of claimants are evidently put off by that process. Therefore, we welcome the simplification of the process, which will put claimants in a more favourable position. Hopefully, offering a more realistic method of enforcing awards will also have the effect of deterring non-compliance in the first place, if it is regarded as a more effective method of enforcement.

160. We also welcome the right to request time to train. That will allow qualified employees the time to study or to train where it will improve performance. It will also assist employers and employees to work together to address skills shortages and to improve skills within the workplace.

161. Mr Daire Murphy (Law Centre (NI)): The consultation that the Department carried out and the response to it were very wide-ranging. As a result, the Bill addresses only a fraction of the outcome of that process. There is a lot of work to be done by the Committee, the Department and interested stakeholders to put flesh on the bones of the remainder of the proposals. We consider that a number of the measures proposed by the Department are in themselves very positive, but we remain concerned that they do not necessarily fit together in such a way as to provide a strategic reform that ensures a fair and coherent system.

162. For instance, a lot of emphasis has been placed on the promotion of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) techniques, such as mediation. We see that as a positive thing, but the Law Centre is very doubtful that that will be an effective panacea in itself for all the ills in the tribunal system. It is far from certain that employers will see a major interest for themselves in engaging in early ADR when the realities of the tribunal system make it so hard for employees to take their cases the whole way through and to win. It is not practical or desirable to make ADR, mediation, and so forth compulsory, but anyone who has experience of employers’ failure to engage with unrepresented claimants in the existing ADR system, which is conciliation, would not necessarily be too confident that that is suddenly going to change by itself.

163. Conciliation operates against a backdrop of an industrial tribunal system in which the deck is very much stacked against the employee, who is most likely to have no professional advice and no representation and who is trying to do their best in an alien environment and is often floundering in that environment. The Law Centre has published a research paper on tribunal reform in conjunction with the University of Ulster and the University of Liverpool, the research for which was funded by the Nuffield Foundation. I understand that that paper was circulated to MLAs; if anyone would like further copies, we can provide them.

164. The legal academics who carried out the research interviewed a wide range of people involved in tribunal systems. One finding was a definite scepticism towards ADR from claimants who had been through the whole process. None of the claimants interviewed felt that the respondents in their cases had attempted to engage in ADR at an early stage. That included those who were in bilateral contact with an LRA conciliation officer. It was felt that the employers preferred to push claimants towards a hearing in the expectation that that would overwhelm them and force them to withdraw and settle for less.

165. Unfortunately, that very much reflects our day-to-day experience as advisers and the responses from a number of organisations. Responding employers are represented by lawyers, and, if the system works in their favour, the lawyers will play that system to maximum advantage. When stringing things out in that way, they are often doing their job well for their client, and it often works. However, against that sort of background, it is difficult to see why employers would suddenly develop an appetite for early ADR unless they were pushed in some way.

166. The other main plank of the Department’s proposals rests on opening up a simpler alternative to the tribunal for disputed cases. It proposes that the current Labour Relations Agency arbitration scheme be expanded to cover all employment law jurisdictions, providing a quicker, cheaper and less legalistic alternative to the tribunal. That sort of forum, where employees can go and present their case themselves and be on more of an equal footing, is what employee representatives have been crying out for for years, but we believe that there is, perhaps, a failure to tie the reform into a coherent system and that that, therefore, could undermine its potential. In the model that we have put forward to DEL, we have pushed for a system in which all appropriate cases would have to go through a simpler, informal, speedy hearing to ensure that the industrial tribunal did not remain as the default setting.

167. In DEL’s model, arbitration remains voluntary, and employers may not see any incentive to participate because, for one thing, they are confident that they can grind the claimant down through the tribunal system. However, we also have a concern, which we have expressed to the Department, that it is clear that employer representatives have strong reservations about an arbitration system with no right of appeal. Under that system, people would simply have to opt for it and to take the outcome. Potentially, that could lead to widespread employer refusal to engage with the system, and, perhaps, that should be looked at again.

168. The researchers who carried out the Nuffield Foundation research on our behalf spoke to one tribunal member, a tribunal judge who had also been an arbitrator in the existing LRA system. That person was quite scathing about what might come out of the consultation and stated that it:

“glosses over the fact that all this was tried before and it failed totally. We had a perfect scheme … it was a shirt sleeves environment. … Nobody wanted to use it. It died simply because of underuse."

That is a cautionary note. We believe that any new system has to be fitted into existing processes in a way that ensures that it too does not die in isolation. New reforms and proposals need to be scrutinised to see how they fit in, and incentives and penalties should be considered to get employers and employees to engage with and utilise those alternative systems. That may involve using pilot projects and keeping a close eye on the outcome of those projects.

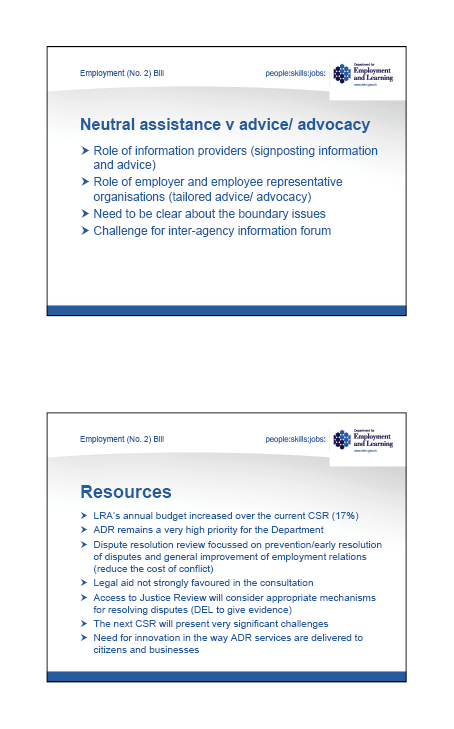

169. The Department’s response also proposes reform for systems of provision of employment advice and information-giving with the establishment of an interagency forum and an information gateway to signpost people to the most appropriate resource. It recognises the distinction between providing information and providing professional or tailored advice, and we welcome that. There is a significant degree of consensus that the Labour Relations Agency cannot offer that sort of advice but can provide the information.

170. It is evident from calls that we have received that a claimant who needs to look elsewhere for tailored advice cannot necessarily receive that from the LRA. We regularly receive callers who are referred to us from the LRA information line, which demonstrates that the agency cannot tackle the problem on its own. In 2008, we received 225 advice calls that had been referred from the agency. So far in 2010, that number has more than doubled to 490. In the past month, advice queries that were referred from the LRA accounted for more than a third of our queries.

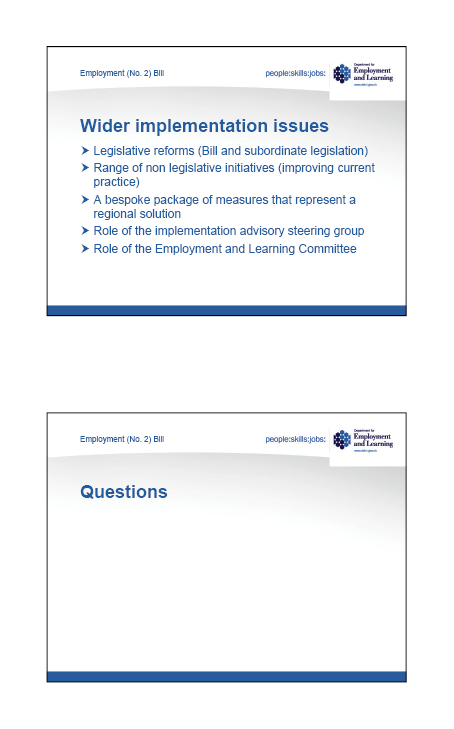

171. Against that background, it is somewhat disappointing that the Department does not intend to provide any additional resources to deliver the advice that is recognised in the paper as being needed. The rationale appears to be that increased uptake of ADR and the impact of the arbitration scheme will be such that it will reduce the need for advice and, indeed, representation. Frankly, we would be delighted if ADR managed to produce those dramatic results, but, for the reasons that we have outlined, we remain doubtful, and rather a lot of eggs appear to be placed in that basket.

172. There remains, in our experience, an acute need for the provision of a proper advice service for workers. Existing structures, including our organisation, are being overwhelmed by the surge in the need for employment advice. The problem with providing a signposting information gateway is that, if you are going to signpost someone somewhere, surely you have to ensure that there is something there when that person arrives. As I said, at the minute, we are being overwhelmed.

173. We are all aware of the effect that economic austerity measures will have here, and I am sure that Committee members are particularly conscious of it. Many more people will lose their jobs, will not be paid their wages and will lose their redundancy payments. Therefore, the number of people who are thrown into contact with the dispute resolution and employment tribunal system is set to rise dramatically. Those people will come from all parts of the country and from all sectors of society, and they will expect a fair and just system to deal with their problem. Therefore, it is more imperative than ever that all stakeholders concerned work to try to give them that. At the moment, such people are likely to feel that they are fighting an uphill and futile struggle without advice or representation, and they can end up feeling disillusioned and resentful. It appears that that could happen to any of us, which might make it easier for us to imagine how we would feel in that sort of situation.

174. We believe that reform of the system must involve a two-pronged approach. First, it must provide a more informal route for resolving disputes through the arbitration system and, crucially, ensure that it is used. Secondly, it must try to make the existing tribunal system fairer and more equal. The single biggest thing that can be done to make the tribunal system fairer, cheaper and more acceptable to the public is to increase the provision of advice and representation for deserving claims. Quite simply, it would level the playing field.

175. It hardly needs to be said that public expenditure is under enormous pressure, but a sound business case can be made that investment in advice and representation can save public money. That is borne out by our experience and by the findings of the Nuffield Foundation research; representation allows cases to settle and shortens hearings.

176. An empirical study, which looked at that issue in detail, was carried out by the central office of Citizens Advice in England in July 2010. We can furnish members with a copy of that study if they want one. It looked at the evidence of the cost benefit and economic value of advice and representation and attempted to quantify the value of that to the state. The study found that, for every £1 spent on employment advice, the state potentially saves £7·13. I am not sure where they got the 13p from.

177. As there is a strong business case for the provision of advice and representation, and it is in the interests of fairness and justice and meets an increasing public need, the issue should be looked at afresh and consideration given to the provision of more resources in that regard.

178. Ms Griffith: I should explain that Daire is a lawyer by trade.

179. We have raised a number of critical issues this morning, which we hope will help to inform the Committee’s approach in the coming months. We ask the Committee to keep the non-legislative proposals, in particular, under review, including the effectiveness of the interagency information and signposting service and the effectiveness of ADR, particularly the arbitration and the uptake of that. We encourage the Committee to have a look at the availability and adequacy of the current advice services.

180. Karen pointed out that there is a lot of common ground between all parties, which is positive. However, I reiterate our view that this is the start of a process to bring about a fairer and more coherent system.

181. The Chairperson: Thank you very much for your presentation. For some time, the Committee has believed that the legislation is a starting point, not the final destination. We are keen to tidy up the Bill as best we can, but to have the Department come back to us with more extensive legislation that will look at the needs of employers and employees. All of us have experience of representing constituents with employment difficulties for whom achieving a resolution was made so long, drawn out and difficult because there was no intention to settle that people just gave up. On a personal level, I am interested in the promotion of social justice and employment law. Trade unions fought too long and too hard to get us some sort of protection and rights for us to give them up too easily. However, there are lessons to be learnt about the problem of lengthy delays and processes that have not had the desired outcome.

182. Do members wish to speak or are we content to note the paper?

183. Mr P Ramsey: I welcome the witnesses and acknowledge the Law Centre’s contribution to the work of Assembly Members. I had two cases at the Derry office last week, not strictly related to employment law — they were more welfare and social security issues — and Danny Breslin was very helpful. We deal with issues across the board with which the Law Centre is more than helpful. At times, it is a lifeline for Assembly Members who are struggling with such matters.

184. We all deal with cases in which people are bewildered by the system and become so frustrated that they want to just pack it in because of the lack of access to precise and specific legal advice. So, there must be signposting, and more so in non-legislative areas. An increase in job losses is expected and with that comes concerns from people about why one person lost their job when someone else did not. I am interested in the resources that the Department currently gives to the Law Centre and others. We are looking at more effective and efficient ways of delivering services. Therefore, if the Law Centre is saying that a business case can be made for an investment that will ultimately save money, the Committee would be keen to hear about how it can assist that when it meets the Department.

185. I am also keen to know the level of advice service being delivered by the Law Centre in each constituency, so that we, at the coalface, know how many people in West Belfast, East Derry or Foyle are being helped. Will you get the Committee some of that information? It may help.

186. Mr D Murphy: If we are able, we would like to try to do that.