| Homepage > The Work of the Assembly > Committees > Education > Reports > Inquiry into Successful Post-Primary Schools Serving Disadvantaged Communities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Volume 1Session 2010/2011First ReportCommittee for EducationInquiry into Successful Post-Primary Schools Serving Disadvantaged Communities

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School Name | Coláiste Feirste |

| School Sector | IM Post-Primary |

| Location - Rural/Urban | Independent Maintained |

| Boys/Girls/Mixed | Mixed |

| Your Name and Contact details | Micheál Mac Giolla Ghunna |

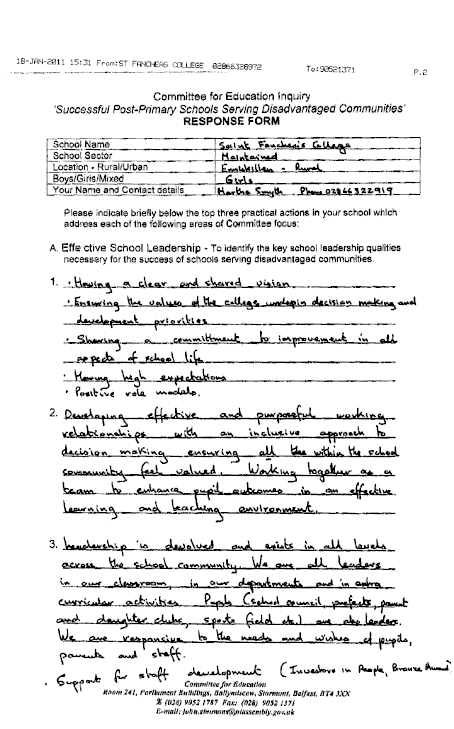

Please indicate briefly below the top three practical actions in your school which address each of the following areas of Committee focus:

1. We have agreed and articulated a clear ethos (Irish language) and vision (the needs of the individual pupil) in order to motivate, energise and direct school improvement work. We regularly review this ethos and vision against school improvement plans.

2. We have developed a culture of school self-evaluation as the basis for planning school improvement. This has helped to build leadership and organisational capacity in the school, particularly middle leadership who lead much of our self-evaluation activities.

3. We restructured and expanded our senior leadership team to include Key Stage Coordinators, an Information Systems Manager and a non-teaching SENCo. We have distributed leadership to various teams focusing on particular school improvement projects.

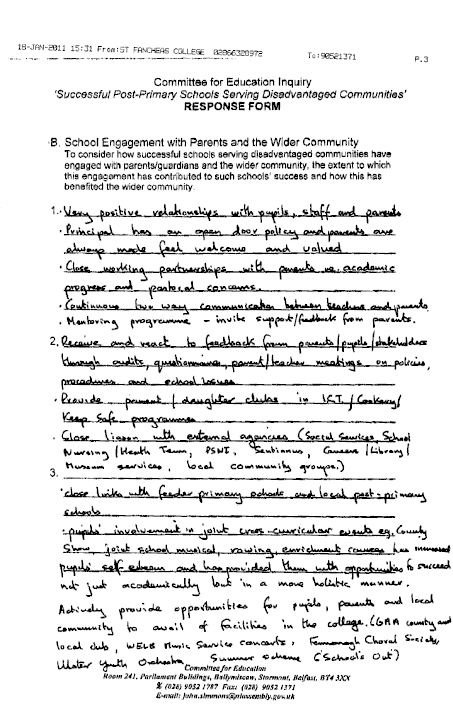

To consider how successful schools serving disadvantaged communities have engaged with parents/guardians and the wider community, the extent to which this engagement has contributed to such schools' success and how this has benefited the wider community.

1. We developed high quality communication with parents and opportunities for involvement in their child's education, particularly in exam classes. We see parents as playing a key role as motivators, organisers and mentors for their children.

2. We appointed a fulltime Extended Schools Corodinator with a community development approach: (i) to develop relationships with community groups in order to give pupils alternative learning opportunities and also to facilitate pupil engagement in community initiatives; and (ii) to attract funding for particular projects such as parental support, learning support, healthy living and creative arts – which build pupils confidence and sense of belonging.

3. We developed opportunities for pupils to engage in community work: for example through NOCN Level 1-2 in Youth Work; NOCN Certificate in Community Development; Certificate in Personal Effectiveness; Gaisce –The President's Award. Pupils also run an Irish language group "An Cumann Gaelach" and assist other community Irish language groups. Pupils gain confidence, positive attitudes, leadership and organisational skills. The community develops a valuable human resource for community regeneration.

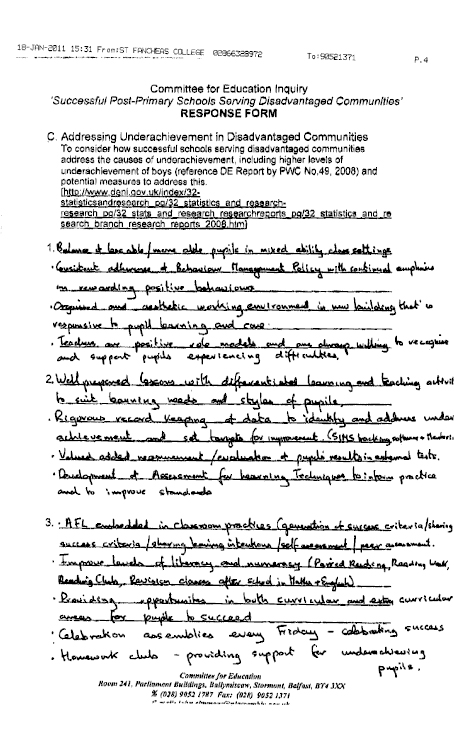

To consider how successful schools serving disadvantaged communities address the causes of underachievement, including higher levels of underachievement of boys (reference DE Report by PWC No.49, 2008) and potential measures to address this.

[http://www.deni.gov.uk/index/32-statisticsandresearch_pg/32_statistics_and_research-research_pg/32_stats_and_research_researchreports_pg/32_statistics_and_research_branch_research_reports_2008.htm]

1. Clear school ethos: the Irish language ethos in the school helps to develop high aspiration, self-belief and a positive identity for pupils. This encourages them to relate better to the school and to engage more positively in the learning process.

2. Pastoral system: we have created a family-type climate which is nurturing and gives pupils a sense of belonging. For example we work hard at maintaining positive and informal relationships; all teachers and pupils use first names; many teachers live in the area or are former pupils.

3. We focus on the needs of the individual pupil. We have a broad range of curriculum choices which meet individual needs, abilities and aspirations; we have invested heavily in learning support resources tailored to individual and additional needs, for example through our Learning Support Centre.

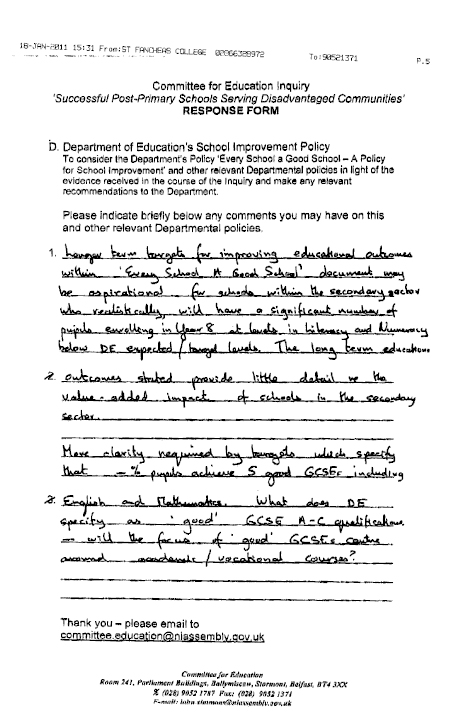

To consider the Department's Policy 'Every School a Good School – A Policy for School Improvement' and other relevant Departmental policies in light of the evidence received in the course of the Inquiry and make any relevant recommendations to the Department.

Please indicate briefly below any comments you may have on this and other relevant Departmental policies.

1. We agree that the four main threads of ESaGS are central to school improvement and therefore pupil attainment.

2. In terms of the Entitlement Framework, the Department's policy mentions the post-primary Irish-medium sector in passing. It does not consider the specific circumstances of the sector and the lack of partners for curriculum collaboration. Coláiste Feirste offers 25 subjects at GCSE and 17 'Level 3' courses post16. We have to carry the financial and other resource costs by ourselves. In addition the 24/27 requirement is irrelevant to the curriculum choices and opportunities of our pupils. What is relevant is that we plan for and deliver a broad range of courses which meet the needs and aspirations of every current pupil.

3. The Department's policy of not funding 'Level 2' courses post16 contradicts the spirit of the Entitlement Framework. Coláiste Feirste offers 5 'Level 2' courses post16 based on the needs, ability and aspirations of particular pupils and aimed at facilitating them to progress to 'Level 3' courses post 18. In addition some courses cannot be studied at 'Level 3'.

Thank you – please email to committee.education@niassembly.gov.uk

As a result 80% of pupils stay on at school after Year 12 and are supported in developing the skills, attitudes and self-belief to pursue successful careers after Year 14.

Three pronged approach to support system:

1. Core learning. The high support class in Year 08 and Year 09 is sub-divided and pupils are taught all of their core subjects in the centre. This reduced ration allows for a greater absorption of learning.

2. Small groups are taken from Year 08-Year 10 classes for group work on English literacy, on Irish literacy and on numeracy work.

3. All Year 08 and Year 09 pupils attend a Literacy Support lesson with a LSC teacher.

Pupils with a statement of special educational need or a diagnosis of ASD (Asperger's to ADHD) are supported. SENCo co-ordinates the support given by appointed classroom assistant to a child. We have a team of 13 classroom assistants who provide support not only for their appointed children, but to individual children who may have been referred by teachers. We support students who have difficulty in completing homeworks or organising themselves for school. Classroom assistants are assigned to pupils for help in class, also.

A number of our pupils may have SEB (Social, Emotional, Behavioural) difficulties at times and the nurturing environment within the centre is key to their emotional adjustment. The centre acts a haven to pupils who cannot cope with their school/home environment.

1. Distributed and Inclusive and Autonomous Leadership based on an agreed and shared vision for the school which fully recognises the characteristics of the school including the social profile of the intake, the place of the school within its community and the disposition of the pupils and parents towards achievement. The span of leadership should extend to Governors and community based organisations, particularly those linked to 'Extended Schools'. Leadership should be strategic, should reflect on the quality of governance, learning and teaching, pastoral care, extra-curricular/enrichment activities and work with other schools and external agencies.

2. Evidentially Supported School Development Plan based on a thorough analysis of relevant data and contextual information matched to a realistic, shared vision for the school. Clear challenging but achievable targets should be set and agreed with effective interrogation of outcomes. Whole school and sectional priorities will always be shared and understood by all relevant stakeholders and progress on these will be monitored. The focus will be on the learning and development of each young person including those with special needs, from other communities and cultures and those with unique gifts. The stable but evolving staff will fully embrace a culture of collaborative professional development and partnership with parents and other relevant agencies.

3. Leading a school is leading a community, particularly in areas of high social deprivation which are mainly in urban settings. In those schools with the best outcomes leadership is motivated to make a difference through engagement, openness and commitment to high standards. The professionalism of all leaders will influence its culture, ethos and strategic direction of the school challenge impediments to success and provide creative solutions to complex issues. The school is characterised by its commitment to learning in all its forms embracing pupils, staff, governors, parents and the wider school community. The school will have a clear focus in preparing young people to make a full contribution to an emerging economy and society.

To consider how successful schools serving disadvantaged communities have engaged with parents/guardians and the wider community, the extent to which this engagement has contributed to such schools' success and how this has benefited the wider community.

1. A purpose of the school is to support families to help children achieve improved learning outcomes. Schools in areas of social disadvantage which have achieved better outcomes have tended to have in range of parent/family/community focussed activities in place, usually established over a period of time. These schools would be recognised as being part of the community and of adding value to that community. Parents will feel welcomed, will respect but not fear or resent teachers and teachers will know the child and the parent and provide support and guidance to them as parents but also as fellow educators. Some of these aspects are harder to achieve in post-primary settings.

2. Communication and Collaboration with the school community and with other schools, organisations, businesses and individuals. This will include exploiting the links established through the cluster of 'Extended Schools' to raise standards. Effective relationships and curricular links with feeder primary schools can enhance this transition and ensure continuous learning. Full implementation of the Entitlement Framework is difficult for schools serving disadvantaged communities, particularly if they are small. It is therefore essential that in addition to relevant, motivating and viable courses, effective arrangements are established with other schools, FE College and training organisations to ensure the provision of appropriate courses.

3. The school can be a focal point for the re-engagement of the community in education through an understanding of the shared role of the parent and the teacher in the education of the child. While predicted around learning the activities can extend to healthy eating, behaviour management, remedial therapies, sporting or cultural activities. A particular feature of successful initiatives has been the use of ICT and sports to get fathers/male partners involved with the school, particularly to encourage boys. The Full Service and Extended Schools have a specific role in some of these approaches.

To consider how successful schools serving disadvantaged communities address the causes of underachievement, including higher levels of underachievement of boys (reference DE Report by PWC No.49, 2008) and potential measures to address this.

1. CCMS subscribes to the principle of 'proportionate universalism' which underpins the entitlements of all children but modifies the extent and nature of support provided to the level of need and the resources available. Children living in disadvantaged communities need greater levels of support than others from more supportive environments. When a school has a critical mass of its enrolment from disadvantaged backgrounds the extent of support and intervention needed multiplies. Unless there have been successful interventions with the family through Sure Start and Nursery some children arrive at school when they are not 'school ready' and the school has a significant role in integrating them to a learning environment. It is likely that the issue of parental confidence will need to be addressed in recognition of the powerful influence of family and community where the child spends 85% of her/his time. Successful schools use every option to address this. If those difficulties are not address in primary school the capacity of the young learner to benefit from intervention in post primary deminishes but some schools have 'broken the cycle' in some ways.

2. Underachievement is best challenged through high quality teaching supported by learners who have a clear understanding of need and a vision and strategy to address it. Success is inspired by enjoyment of learning which is a response by the child to learning that is motivating, generally reflective of knowledge by the teacher of the child's preferred learning style and the availability of appropriate stimuli and resources. This differentiated learning reinforces positive behaviours and attitudes through teachers who are skilled at managing negative behaviours and are empathetic to needs. In successful situation teachers have a desire to work in that environment rather than simply being there by the circumstance of the 'first job to come along'.

3. All children learn at their own pace but boys tend to follow in the wake of girls, particularly during the primary years. Good teachers take the child from where he or she is rather than forcing situations. This means reinforcing positive dispositions to learning and using these to extend learning, particularly in literacy. Expectations need to be managed and parents engaged in understanding reactions and choosing the appropriate response. Successful schools actively involve parents and a range of external resources, including counsellors to explore the trigger points which motivate learning and manage the barriers to learning. This becomes more challenging as children grow older, particularly where key learning thresholds have not been achieved reinforcing again the critical importance of early intervention and prevention.

To consider the Department's Policy 'Every School a Good School – A Policy for School Improvement' and other relevant Departmental policies in light of the evidence received in the course of the Inquiry and make any relevant recommendations to the Department.

1. CCMS broadly supports ESAGS, however, it would make a number of points to contextualise its position and propose what ought to be done.

Impediments: There are structural/legislative barriers to learning and which contributes to the perpetuation of underachievement including;

2. Lack of Policy Coherence: CCMS believes that ESAGS should be DE core policy with all other policies aligned to it. This is not currently the case. Key support policies are LMS formula, 0-6/Literacy and Numeracy/Special Needs, some aspects of School Development Planning, Sustainable Schools Policy, 'unsatisfactory' procedures, governance and inspection regimes. The Council believes that a policy on 'Earned/Accountable' autonomy should be introduced to promote self-evaluation and self-improvement. There is also a need to look at teacher terms and conditions of service and a greater alignment in the working of the ETI, Employing Authorities and CASS with respect to targeting support to under performing schools.

3. Broader Policy Alignment: Education needs to sit at the centre of Executive thinking particularly on the economy and this needs to be reflected in the next Programme for Government. There needs to be a long term strategy to re-balance the economy through education from early years (0-3) to the range of economically focused, applied courses as part of the Entitlement Framework. Cultural change is needed in society to embrace the mindset of the private sector over the perceived security of (mainly) public sector focussed public sector employment aspirations including the traditional ' professions' . There needs to be a greater cohesion between the formal school system and the economy and a recognition of the positive potential of a range of agencies and communities working together to improve society.

CCEA's responsibility is to provide advice to the Department of Education on matters related to curriculum, assessment and qualifications and to support schools in these areas. Although CCEA is a key stakeholder and part of the education support service it is not directly involved in managing school performance, target setting or performance intervention.

A relevant curriculum, with literacy and numeracy at its core, fit for purpose assessment arrangements and meaningful qualifications can help support strategies for raising standards and closing the achievement gap that we know exists in Northern Ireland. However, addressing poor or underperformance of individuals and schools is dependent on key factors of;

In their study of 'How the world's best performing school systems come out on top' (McKinsey & Company 2007) Mckinsey recognise that although education systems around the world have striking differences, there are a number of fundamental similarities between the highest performing systems;

These principles apply to school leadership, ensuring that the right people are selected to become leaders and that they are developed and supported. In doing so, these individuals can take ownership of policy, make it relevant in their schools, develop their staff and manage performance to ensure every pupil can reach their full potential.

Policies alone cannot improve standards and opportunities for children and young people. It is the way in which policy is implemented that makes a difference. We know that some schools serving disadvantaged communities perform very well, adding considerable value to the life chances of their pupils. Others in similar circumstances do less well.

The factors relating to improving standards of literacy and numeracy identified by ETI all relate to effective school leadership having a focus on school improvement and the ability of leaders to put in place strategies to improve learning and manage performance.

Societal influences have a major impact on pupil achievement; therefore attention should be given to parental involvement and community engagement. This is not without its challenges. For example, many parents do not engage with education because of their own poor literacy and numeracy skills, so this deficit should be considered. Consideration should also be given to communication with parents. However, 'one size does not fit all' and while the system may be able to define the vision, aims and objectives that should be incorporated, principals and teachers may be best placed to decide on the appropriate communication strategy with the parents of their school.

If communities are to value the contribution of education in improving life chances, then schools need to be perceived as being at the heart of their communities and meeting the needs of those communities. The promotion of initiatives such as Extended Schools may be beneficial in this regard. The Extended Schools policy is intended to support those schools that draw pupils from some of the most disadvantaged communities to provide a range of services and programmes outside the traditional school day to help meet the needs of pupils, their families and wider communities. 0-3 are critical years and much could be gained by supporting parents, providing motivation and building self confidence working in communities.

Consideration should be given to the findings and recommendations of the PWC Report on Literacy and Numeracy in Northern Ireland (2008). In particular, that the factors impacting on attainment are complex and interactive (including management type, socio-economic context and gender) and that generalisation is therefore difficult.' It is evident therefore that no one initiative or intervention is a 'cure-all' and that there are no instant solutions. Indeed, the education sector by itself cannot effect major changes without taking socio-economic factors into account.

However, it is evident that there is variety of provision in schools and, based on its international literature review and fieldwork, the PWC report identifies a number of factors at a school level which may help improve pupil attainment, such as:

These factors also underpin the school improvement agenda of Every School a Good School and its associated Literacy and Numeracy Strategy. It is therefore vital that this is seen as a policy priority and that there is a coherent and unified strategic approach to supporting schools in this key area. This will enable schools to focus on ensuring that their pupils have the best provision possible according to their needs.

Research in Germany (EURYDICE at NFER, 2007) shows that deficits not compensated for before school entry may lead to school failure; therefore, it is crucial that children receive the best start possible and that early intervention is provided which may prevent the need for later remediation. These interventions need to be developed locally to meet the specific needs of parents and children. Provision of pre-school places staffed by qualified teachers with SEN expertise could be considered.

There are Early Intervention Strategies running throughout Scotland which are developed by each Local Authority to meet the specific needs of the children in their area. In Glasgow nurture classes/rooms have been developed from pre-school to Year 1 for the most deprived children.

'On average across the OECD area, public spending on children under the age of five represents just 24% of all spending on children up to the age of 18. Increasing spending on our youngest citizens, particularly in the areas of health and education, and especially for disadvantaged children, will help to improve social equity as those children grow up.' (Doing Better for Children: OECD, 2009).

Individual measures if taken in isolation may result in disappointing outcomes. A co-ordinated consistent approach to under achievement is required which focuses on a range of issues including school leadership, school performance, effective teaching and learning intervention, early pre-school investment and parental involvement.

Department of Education School Improvement Policy Every School A Good School seeks to address these issues in a coherent way. It is important that school improvement policy is implemented in a consistent way, taking account of lessons learned from past experiences/other jurisdictions. Greatest consistency can be achieved by a single organisation being responsible and accountable for implementing policy.

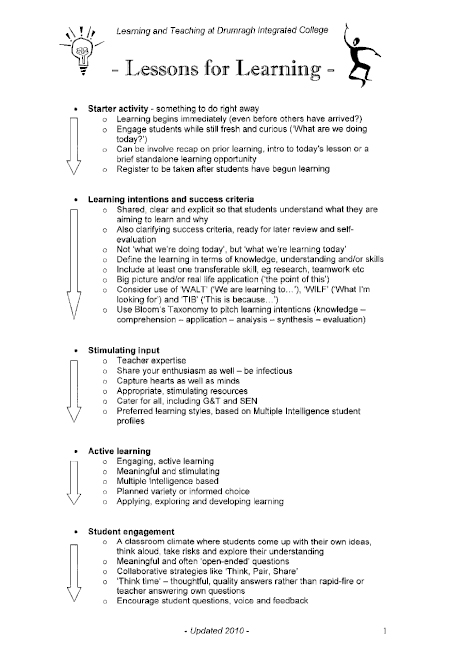

The Revised Northern Ireland Curriculum permits the flexibility for schools to adapt approaches to learning and teaching which suit the individual needs of their pupils. At the same time, there are elements of the NIC which may contribute to meeting the specific needs of pupils as identified in the EDPWC paper. These include:

The requirement to offer greater breadth and balance in the courses and pathways available to young people provides an opportunity for post primary pupils to have a greater choice and flexibility by providing them with access to a wide range of learning opportunities suited to their needs, aptitudes and interests, irrespective of where they live or the school they attend.

The Chief Inspector's Report 2008-2010 identifies three crucial areas for

It is therefore important that there is effective communication and collaboration between those responsible to share information, practice and resources, whether between schools (for example through Area Learning Communities or cross-phase primary and post-primary) or between government departments and support organisations (DE, DEL, DHSSPS etc).

10 December 2010

(Mission statement of the Dean Maguirc College.)

1. The Department is putting in place a range of policies aimed at promoting the raising of standards across the system and enabling every young person to achieve to her or his full potential.

2. 'Every School a Good School – a policy for school improvement' was introduced from April 2009 and is our overarching policy for raising standards. It sets out our very clear commitment to support schools to improve outcomes for pupils and recognises the centrality of classroom teachers, supported by effective school leaders, in helping pupils to reach their full potential. The key underpinning argument behind the policy is that raising achievement is, above all, the responsibility of the school. Self-evaluation, informed by the effective use of data, leading to sustained self-improvement, and with appropriate support, is therefore at the heart of the policy.

3. The policy starts from the basis that there is much good practice within our schools to build on and learn from – the challenge is to ensure that this is spread across all schools. It is recognised that the challenge may be greater for schools who are struggling with the effects of socio-economic deprivation or serving communities where the value placed on education is not as high as it might be. However, the policy stresses the importance of having high expectations for every young person and providing pupils, and schools, with the support they need to overcome any barriers to learning and fulfil their potential.

4. The policy sets out four characteristics of a successful school as:

i) Child-centred provision;

ii) High-quality teaching and learning;

iii) Effective leadership; and

iv) A school connected to its local community.

5. The characteristics are based on inspection evidence and were informed and developed through consultation and wider research evidence. These characteristics are not specific to any particular type of school; rather they apply to all schools. When these characteristics are all present, there is every likelihood of success. Variation among schools in the extent to which these characteristics are present will lead to variation in performance between schools. There may be cases where:

6. The policy sets out ambitious, long term targets for improving educational outcomes, against which we will measure progress in implementation. It also includes an implementation plan, setting out the actions in six key policy areas:

i) effective leadership and an ethos of aspiration and high achievement;

ii) high quality teaching and learning;

iii) tackling the barriers to learning that many young people face;

iv) embedding a culture of self-evaluation and self-assessment and of using performance and other information to effect improvement;

v) focusing clearly on support to help schools improve – with clarity too about the place of more formal interventions where there is a risk that the quality of education offered in a school is not as high as it should be; and

vi) increasing engagement between schools, parents and families, recognising the powerful influence they and local communities exercise on educational outcomes.

7. The school improvement policy includes a requirement to provide focused support for schools which, as a result of inspection, are found to be offering less than satisfactory provision for their pupils. This support is provided through the Formal Intervention Process, introduced from September 2009.

8. Through the Formal Intervention Process, the school receives tailored support from the relevant Education & Library Board, supported where appropriate by the relevant sectoral body. The school commits to working to deliver an agreed action plan, quality-assured by ETI, designed to address the areas for improvement identified through inspection. The focus throughout is on ensuring that pupils receive the highest possible quality of teaching and learning so that they can achieve to their full potential.

9. The school improvement policy will be supported and complemented by other key DE policies, including the removal of academic selection and introduction of Transfer 2010, the revised literacy and numeracy strategy, the revised curriculum and assessment arrangements, the Entitlement Framework, the Review of Special Educational Needs & Inclusion, the Supporting Newcomer Pupils policy and Extended and Full Service Schools.

10. The Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry – Bright Futures programmes were introduced from the 2008/09 school year to specifically address the link between underachievement and social deprivation in Belfast and Derry.

11. The Achieving Belfast programme is targeted at 17 (13 primary and 4 post-primary) of the lowest performing schools in the BELB area. The Board is providing the schools with intensive support for literacy, numeracy and school improvement (including the deployment of 10 peripatetic teachers) and intends to develop this approach to work with other agencies to provide wrap-around support to take account of socio-economic issues.

12. Achieving Derry – Bright Futures encompasses all schools (pre-school, primary and post-primary) in the Derry City Council area, along with youth provision. The WELB is working with partners in health and social services, neighbourhood renewal, and the local business, voluntary and community sectors. The focus is on a whole school approach to meeting the needs of children most at risk of underachievement.

13. Interestingly, the Boards have adopted different approaches and the respective learning will inform discussions and decisions on the most effective interventions in tackling educational underachievement. Both programmes are long-term interventions, therefore it is recognised that there may not be immediate major improvements in educational outcomes achieved by pupils. However, the Department commissioned the Education & Training Inspectorate to carry out a formative evaluation of the programmes to make sure that they are established on sound, evidence-based foundations and that early implementation is planned in a way that will deliver the expected longer term improvements. The ETI report was published in May 2010. The Boards have accepted the findings and are preparing action plans in response to the areas for improvement identified in the report.

Department of Education Evidence

1 Introduction

2 The Characteristics of Effective Schooling

3 Addressing Barriers to Learning

4 Promoting the Sharing of Best Practice

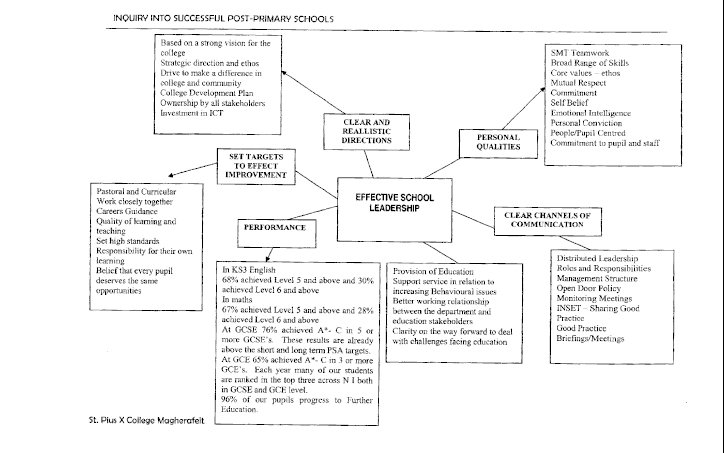

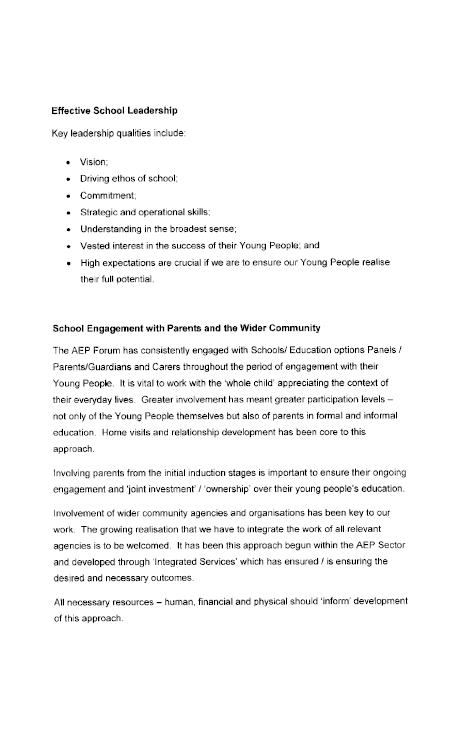

5 Effective School Leadership

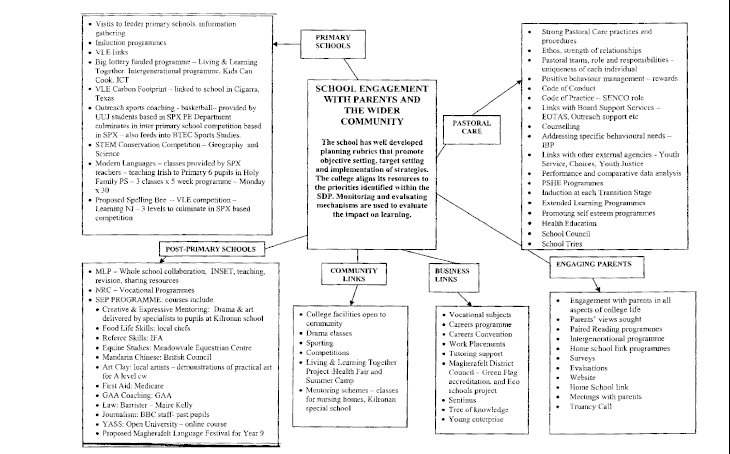

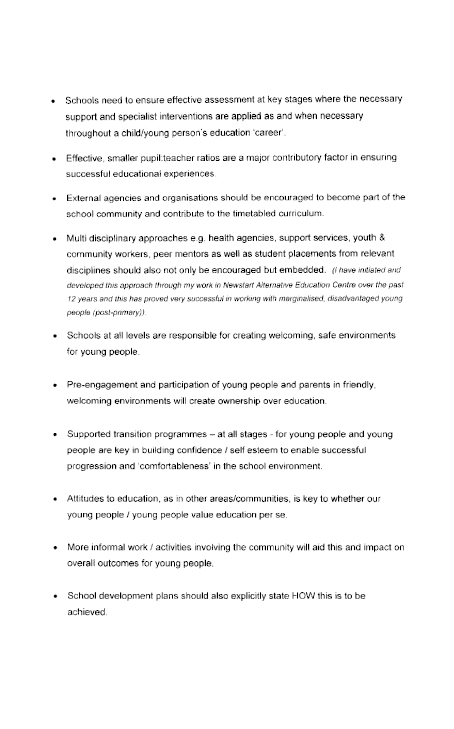

6 School Engagement with Parents and the Wider Community

7 Addressing Underachievement in Disadvantaged Communities

8 Department of Education School Improvement Policy

Annexes:

A ETI's St Colm's High School, Belfast – Report of an Inspection in November 2010

ETI's Edmund Rice College, Glengormley – Report of an Inspection in November 2010

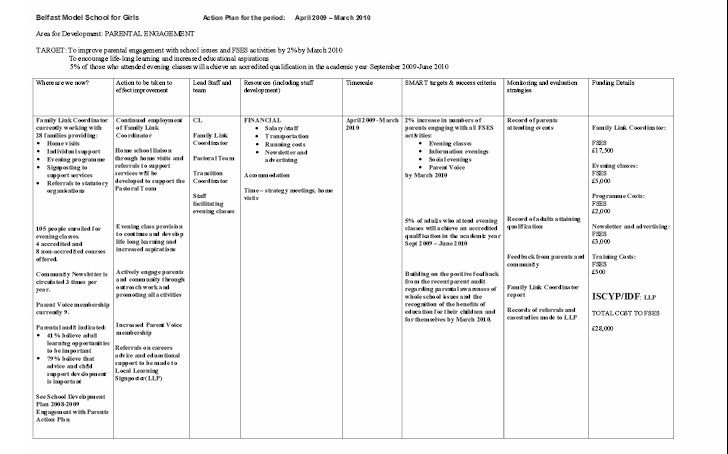

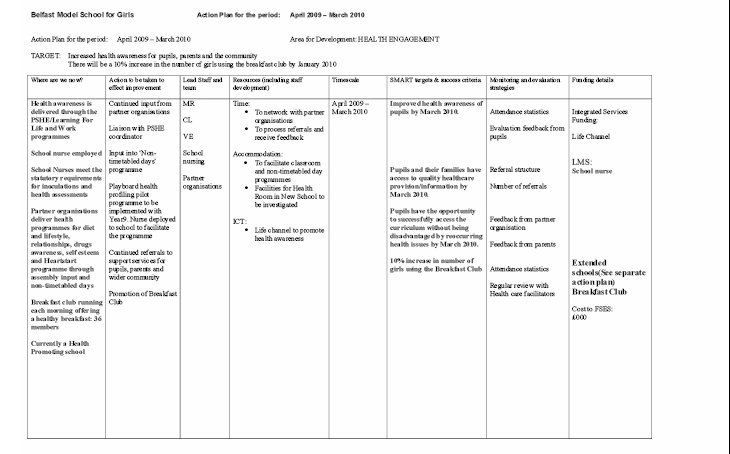

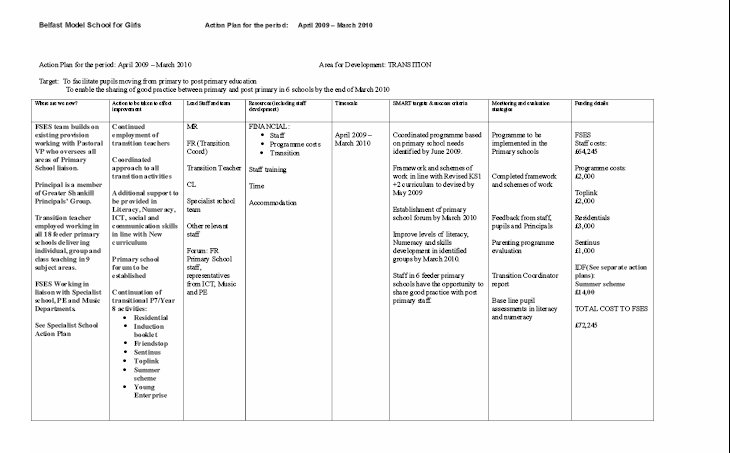

B Examples of good practice from Extended Schools Programmes.

C ETI's Evaluation of Extended Schools July 2010.

D DE Circular On Extended Schools.

E ETI's Evaluation of Literacy and Numeracy in Primary and Post-Primary Schools: Characteristics that Determine Effective Provision 2007-08.

F Full Service Schools Evaluation Reports 2009-10.

G ETI's Evaluation of the Early Progress of the Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry – Bright Futures Programmes May 2010.

1.1 This paper provides the Department of Education's evidence submission to the Committee and follows the Inquiry Aims and Terms of Reference.

2.1 Every School a Good School – a policy for school improvement (ESaGS) is the Department of Education's overarching policy for raising standards across all schools and is based on the premise that raising standards is first and foremost the responsibility of the school; it recognises the centrality of classroom teachers, supported by effective school leaders, in helping pupils to reach their full potential and gives the Department's very clear commitment to support schools to improve outcomes for pupils.

2.2 ESaGS identifies the four characteristics of a successful school, with associated indicators, which are based on research and inspection evidence and developed through consultation. These characteristics apply to all schools and are identified as:

i) Child-centred provision;

ii) High-quality teaching and learning;

iii) Effective leadership and an ethos of aspiration; and

iv) A school connected to its local community.

2.3 ESaGS starts from the basis that there is much good practice within our schools to build on and learn from – but this needs to be embedded across all schools. It is recognised that the challenge may be greater for schools dealing with the effects of socio-economic deprivation or serving communities where education is not as highly valued as it might be. However, we know there are schools in such circumstances achieving very good outcomes for their pupils (there are also schools in much more favourable circumstances where pupils perhaps are not doing as well as might be expected). ESaGS therefore stresses the importance of having high expectations for every young person and providing schools with the support they need to help pupils overcome any barriers to learning and fulfil their potential.

3.1 International research consistently shows that early identification, and the implementation of early, appropriate support interventions, enables children to catch up with their classmates, reducing the risk of long term underachievement and disaffection.

3.2 This whole child approach recognises that the education system has a part to play in:

3.3 Successful schools, working on the underlying principle of inclusion, develop the capacity of the school workforce to understand the learner's needs and adjust the learning environment and teaching strategies to effectively meet those needs.

3.4 The Department has developed or is developing a number of inter-related policies or programmes to support schools in providing the support children and young people need to learn effectively. However, it is important to note that the role of schools in supporting young people is complementary to the role of other sectors, such as health and social services. It is vital that the sectors work together in a multi-disciplinary approach for the benefit of the young people. In education, the ultimate goal is to raise educational standards achieved by the learners so as to prepare them better for life and work. Therefore, policies or programmes are an integral part of the overarching raising standards agenda articulated in "Every School a Good School". The policies are:

4.1 Through inspection, we can identify schools that successfully put the characteristics set out in ESaGS into practice. One example of 'outstanding' and one of 'very good' practice is attached as Annex A.

4.2 The Department is committed to promoting more effective identification and sharing of good practice to embed the four characteristics of ESaGS across all our schools. We have required this to be central to the support provided to schools by the Education & Library Boards and CCEA (and CCMS where appropriate). For example, principals and teachers identified as demonstrating good practice are leading the delivery of professional development events; they are also providing support to schools where areas for improvement have been identified through the inspection process, including schools in the Formal Intervention Process. Personnel from schools which have been particularly successful in supporting pupils with special educational needs will be delivering capacity building programmes for school leaders and teachers in the coming months. The Boards are also developing ESaGS.tv, a web-based platform that will facilitate sharing of best practice and host video case-studies featuring schools identified through inspection as 'outstanding'/'very good' or as having made substantial improvement.

5.1 Effective school leadership has been shown by inspection and research evidence to be central to school improvement. It involves getting the right people to be school leaders, providing them with the right skills, and ensuring their focus is on teaching and learning.

5.2 Successful school leaders will:

5.3 The McKinsey (2007)[1] report commented that: 'essentially all successful school leaders draw on the same repertoire of basic leadership practices.' Research by the National College for School Leadership (NCSL) shows that the core practices of successful schools leaders are:

i) setting direction – from a sense of moral purpose by motivating their colleagues and building a shared vision with high expectations for the school's future;

ii) developing the capacity of people – supporting individuals, giving intellectual stimulation and setting an appropriate example;

iii) (where necessary) redesigning the organisation – building a culture of collaboration, restructuring the way the school works, building productive relationships with families and communities and connecting the school to its wider environment; and

iv) managing the programme for learning and teaching – staffing it appropriately, providing necessary support and resources for staff and pupils.

5.4 The qualities required of school leaders are reflected in the following indicators of effective practice:

5.5 Successful leaders see pupil achievement as having behavioural, academic, personal, social and emotional dimensions, reflecting the four characteristics of ESaGS; their strategies to combat underachievement will reflect this and their selection and combination of leadership practices will depend on the context in which they are working. Successful leaders working in disadvantaged communities may make greater efforts to effect improvements across these inter-connected areas, especially through the leadership they provide and the culture and aspirations they foster (reflected in the school's ethos, pupil behaviour, motivation and engagement).

6.1 Research shows the powerful influence that effective engagement with parents, and the community served by the school, can have on the outcomes achieved by its pupils.

6.2 This underpins DE's Extended Schools (ES) programme, which has a clear focus on improving educational outcomes, reducing barriers to learning, and providing additional support to help improve the life chances of disadvantaged children and young people. Over 70 post-primary schools received Extended Schools funding in 2010/11. Successful extended schools act as hubs of their local community; they:

Examples of good practice are attached as Annex B.

6.3 The Education & Training Inspectorate (ETI) published An Evaluation of Extended Schools July 2010, (see Annex C), which found that:

"in almost 90% of cases where Extended Schools are serving disadvantaged communities effectively, significant improvements are evident in the educational outcomes and the personal and social well-being of pupils. Extended Schools activities are frequently improving the lives of parents and helping them re-engage with education following their own, often poor experiences and perceptions of schools".

6.4 The Report identifies the key characteristics of effective practice, based on inspection evidence from visits to 20 Extended Schools (including 10 post-primaries). It also includes case studies illustrating how schools are successfully delivering on the aims of the ES programme. The Report informed DE's Circular 2010/21, which provides updated guidance for schools on the Extended Schools programme (Annex D).

7.1 There are complex and interacting factors contributing to pupil achievement. However, ESaGS sets out the key, and interdependent, factors for raising standards and tackling underachievement in all our schools, including those serving disadvantaged communities (child-centred provision, high quality teaching and learning, effective leadership and an ethos of aspiration, and strong links between schools and their communities).

7.2 The ETI has published An Evaluation of Literacy and Numeracy in Primary and Post-Primary Schools: Characteristics that Determine Effective Provision 2007-08 (Annex E). The report was based on inspection visits to a sample of schools with a high proportion of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, some with strong performance and others with poor performance. It explains how schools serving disadvantaged communities provide high quality teaching and support for pupils to enable them to achieve good outcomes in literacy and numeracy.

7.3 Inspection and research evidence clearly shows the central role of the class or subject teacher in supporting each child to fulfil their potential. The class teacher should have high expectations for each child and provide high quality teaching and learning experiences. Teachers should employ a range of strategies that are engaging and appropriately tailored to meet the differing needs and learning styles of pupils. Teachers also need to monitor the progress of individual pupils and intervene early to provide appropriate support to overcome any difficulties pupils may be having.

7.4 We are still dealing with the legacy of the transfer test. We know how important it is for young people to master the basics from an early age. Yet for too long, the primary curriculum was distorted by preparation for the tests. Those not entered for the tests were often given 'filler' exercises, while efforts focused on preparing those entering for the tests. Non-selective post-primary schools had to invest significant efforts in boosting the self-esteem of those pupils branded as 'failures' by the test before they could even begin the important work of further developing their literacy and numeracy skills.

7.5 In addition to high quality teaching and learning, successful schools put in place effective arrangements to support pupils to overcome any barriers to learning they may face and achieve good outcomes in literacy and numeracy (e.g. arrangements to support those with special or other additional educational needs or with needs for additional pastoral care). This often involves working in partnership with other organisations, such as health agencies or community and voluntary groups. Extended Schools (see section 5 above) work in partnership with families and the community to provide this support for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

7.6 The Department is working through the Belfast Education & Library Board to pilot Full Service provision in two areas which suffer from high levels of socio-economic deprivation, in one with support from the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools. The two pilots are:

a) Full Service Schools at the Boys' and Girls' Model Schools in North Belfast; and

b) Full Service Community Network (FSCN) in Ballymurphy.

7.7 Full Service provision goes beyond extended school programmes by offering substantial additional programmes and activities to help tackle barriers to learning and support children to achieve their full potential. It enables key statutory and voluntary agencies and community groups to come together and deliver comprehensive and cohesive services to meet the educational, health and well-being, and employability needs of pupils, parents and the whole community. Further information on the Full Service programmes are included in their 2009/10 annual report, attached as Annex F.

7.8 The Department has also commissioned programmes to address the link between underachievement and social deprivation in Belfast and Derry, namely Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry – Bright Futures, introduced from the 2008/09 school year. Achieving Belfast is targeted at 17 (13 primary and 4 post-primary) of the lowest performing schools in the BELB area. The BELB is providing the schools with intensive support for literacy, numeracy and school improvement (including the deployment of 10 peripatetic teachers). Achieving Derry – Bright Futures encompasses all schools (pre-school, primary and post-primary) in the Derry City Council area, along with youth provision. The WELB is working with partners in health and social services, neighbourhood renewal, and the local business, voluntary and community sectors. The focus is on a whole school approach to meeting the needs of children most at risk of underachievement. The ETI published An Evaluation of the Early Progress of the Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry – Bright Futures Programmes in May 2010 (see Annex G).

7.10 Decisions on future funding for programmes such as Extended and Full Service Schools, Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry – Bright Futures cannot be taken until after the final Budget has been agreed by the Executive. The Executive launched a draft Budget, providing draft Departmental spending plans over the next four years, for consultation from 15 December 2010 to 9 February 2011. Following the consultation, the Executive will meet to consider and agree a final Budget. In the interim, the Minister will be considering the implications of the draft Budget for education and will publish details of her spending proposals on the Department of Education's website. In drawing up these proposals the Minister has made it clear that she will seek to drive out inefficiencies, cut bureaucracy and protect frontline services as far as possible. All decisions will also be based on the key principles of identified need and equality.

8.1 DE has put in place its own arrangements to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the school improvement policy. These include monitoring progress against targets for improving educational outcomes and evidence from ETI inspections on the overall quality of provision in schools. The Department holds the Boards to account for the outcomes achieved by schools in their areas and the support provided by the Board. The Department has also published an implementation plan, detailing actions being taken to give effect to the policy. The Department has published its first annual report on progress made against the action plan (for the 2009/10 year) on its website and a copy of the report was sent to the Committee on 28 September 2010.

8.2 The Department will consider any recommendations made by the Committee as a result of its Inquiry in relation to the school improvement policy.

[1] Barner, M. & Mourshed, M. (2007). 'How the world's best-performing school systems come out on top.' McKinsey & Company

Several of the documents submitted by the Department for Education can be found at the following websites:

Post primary inspection St. Colm's, Twinbrook, Belfast

http://www.etini.gov.uk/index/inspection-reports/inspection-reports-post-primary/inspection-reports-post-primary-2010/standard-inspection-st-colms-high-school-twinbrook-belfast.htm

Post primary inspection Edmund Rice College, Glengormley

http://www.etini.gov.uk/index/inspection-reports/inspection-reports-post-primary/inspection-reports-post-primary-2011/standard-inspection-edmund-rice-college-glengormley.htm

An Evaluation of Extended Schools July 2010

http://www.etini.gov.uk/index/surveys-evaluations/surveys-evaluations-post-primary/surveys-evaluations-post-primary-2010/an-evaluation-of-extended-schools-july-2010-post-primary.htm

DE Circular: Extended Schools – Building on Good Practice

http://www.deni.gov.uk/extended_schools_circular_2010.pdf

An Evaluation of Literacy and Numeracy in Primary and Post-Primary Schools: Characteristics that Determine Effective Provision

http://www.etini.gov.uk/index/surveys-evaluations/surveys-evaluations-post-primary/surveys-evaluations-post-primary-2008/an-evaluation-of-literacy-and-numeracy-in-primary-and-post-primary-schools-characteristics-that-determine-effective-provision-post-primary.htm

An Evaluation of the Early Progress of the Achieving Belfast and Achieving Derry Bright Futures Programmes

http://www.etini.gov.uk/index/surveys-evaluations/surveys-evaluations-post-primary/surveys-evaluations-post-primary-2010/an-evaluation-of-the-early-progress-of-the-achieving-belfast-and-achieving-derry-bright-futures-programmes-post-primary.htm

Examples of Good Practice in Extended Schools (Post-Primaries)

Extended Schools demonstrating good or best practice:

The examples of good practice provided below, while not attributable, illustrate some of the benefits and positive impacts of extended schools programmes. These are based around the two themes of Engagement with Parents and the Wider Community and Addressing Underachievement and have been evidenced from each school's Extended Schools Annual Reports for the 2009/10 year.

Further good practice examples can also be accessed via the Northern Ireland Extended Schools Information System www.niesis.org

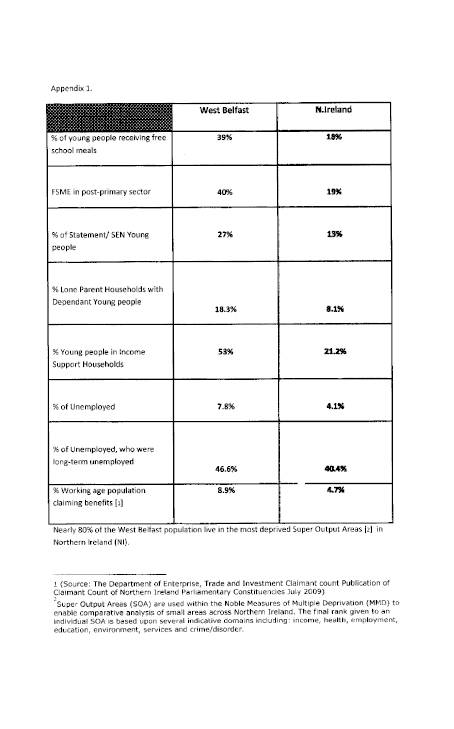

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 37%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 88%

Extended Schools activities

In 2007-08, the school created a new Pastoral Support Centre including the appointment of a dedicated Parent Support Officer to work in that centre alongside key members of the existing Pastoral Support Team. The school also participates in the Greater Falls Extended Schools Cluster and the Full Service Community Network.

Extended Schools funding was used towards a variety of activities during 2009/10 including:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 36%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 91%

Extended Schools activities

This school is part of the Greater Falls (GF) Cluster and participates in the Full Service Community Network. The school's ES co-ordinator is the Irish Medium representative on the GF Cluster Steering Group and West Belfast Neighbourhood Renewal Partnership Board Education Sub-group.

Extended Schools funding in 2009/10 was used towards:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 23%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 70%

Extended Schools activities

This school participates in a cluster with 2 other schools including a maintained post-primary with whom they collaborate on cross community projects. Extended Schools funding in 2009/10 was used towards the running of various activities including:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME – 37%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11 - 62%

Extended Schools activities

This school is a member of an ES Cluster working in partnership with 2 other local post-primaries. The school has its own multi-function fitness suite, which is used by members of the community on a daily basis. Extended Schools funding is being used towards the running of various activities including:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 22%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 58%

Extended Schools activities

The school is a member of the Inner East Belfast Cluster with 2 other post-primaries and 5 local primary schools. Extended Schools funding is being used towards a wide range of activities including:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 53%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 88%

Extended Schools activities

The school works alongside 4 other post-primaries and the Brandywell and Bogside Health Forum as part of their Extended Schools Cluster and provides a wide range of Extended Schools activities to address underachievement and overcome barriers to learning for their pupils. The main elements to this programme include the Saturday school which operates throughout the year every Saturday morning. Over 110 pupils regularly attend and this programme is linked to a local controlled co-educational no-selective school. An Easter Study camp takes place over the Easter break every year and gives exam students additional support with study during this critical preparation period. The school also provides Microsoft Academy training courses for parents and the community in the evenings.

Other Extended Schools activities on offer include:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 34%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 66%

Extended Schools activities

The school is a member of the Newry and Mourne Extended Schools Cluster and collaborates with 1 other post-primary, 7 primaries and 1 Special School in the local area. Extended Schools funding is being used towards the running of various activities including:

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

School Demography

5 Year Average FSME: 34%

Pupils enrolled from an NRA/30% most disadvantaged wards 2010/11: 77%

Extended Schools activities

In 2009/10, the school worked in partnership as part of a cluster with 2 local Primary Schools. Extended Schools funding in 2009/10 was used towards the running of various activities including:-

Impact of activities funded through Extended Schools (source: the school's 2009/10 Extended School report)

Gerard Mc Mahon

Project Manager

June 2010

It is with great pleasure that I introduce the Annual Report for the Full Service Community Network (FSCN). The report highlights the activities, outcomes and priorities as represented in the action plan agreed by the project board.

The FSCN seeks to enhance life chances for all our young people by ensuring educational attainment through addressing the needs of the children, their families and the local community in the area served by the West Belfast Partnership Board and specifically those areas bounded by the Neighbourhood Renewal Areas of Upper Springfield and Greater Falls.

The overall strategic model utilised by the network serves to consolidate existing government strategies and improve education policy coherence by working with and through other statutory, voluntary and community organisations.

Full Service Community Network is focused around six key themes:

It delivers these themes through a series of objectives. Comprehensive family support services address education, health and well-being and employability needs which are being delivered through integrated and improved connected working across a range of statutory and voluntary agencies and community groups. Using this pilot approach, the project is developing the network as a model of good practice for 'Full Service' provision. FSCN seeks to fundamentally challenge and change (for the better) the way that services are delivered by providers and used by our clients.

In the year 2009/10 the FSCN has demonstrated that it has acted as a catalyst to bring the resources of other organisations to the point of need rather than acting as a fund holder.

In this year the project has been successful in continuing to promote and build a 'Team of Teams' approach, working through a range of agencies based on agreed shared outcomes and aspirations. The aim is to create a pathway of care and to support educational development and aspiration for children, their families and the community.

I hope you find the report interesting, informative and most of all challenging in both the objectives of the FSCN and its methodologies.

Chairman

In this, the first Annual Report of the Full Service Community Network (FSCN), the project board presents the background to the FSCN, a summary of the FSCN's spend for the year to 31 March 2010, and some key metrics, indicating the FSCN's progress towards its objectives, again in the year to 31 March 2010.

As this is the first Annual Report, it is important to establish the context leading into 2009/10. While 2009/10 was a significant period in the life of the FSCN, the focus in the preceding year was on the appointment of staff, induction and initiating the operational and strategic processes that would take the project forward.

During that time relationships and trust with partners were nurtured and cultivated in advance of the official launch in April 2009. The tender for primary school counselling was progressed through the auspices of the Belfast Education and Library Board, with Barnardo's NI the successful applicant. This service would eventually prove to be the cornerstone of the need-based provision that is delivered through the FSCN.

Also at this time, the final members of the team were recruited, namely the two educational development workers and the two 'transition workers', and a process of team management was being devised. The intention was to create a structure that would bring together existing strategies (such as Extended Schools and Achieving Belfast) with policies and initiatives from other organisations in the statutory, voluntary and community sectors. While it was important to have a particular project identity it was equally important that the members of the FSCN team worked with and through other teams from other organisations. The specific aim was to create a culture of a "team of teams" with the common purpose of supporting children and families to raise academic achievement through specific activities in the action plan.

From the beginning of 2009/10 programmes of work for the educational development workers and the transition workers were being delivered through schools and community groups. The role of the Extended Schools' cluster co-ordinators was important as they eased the way for the workers into the various schools associated with each cluster. While specific services were being delivered at the point of need by the workers it was equally vital that they drew in other services to support families. These new contacts and connections are a crucial part of the FSCN: particularly as many of them are resourced by other organisations and are not a draw on the FSCN budget. There are many examples of how the team has identified a need, sourced the service and brought the service to the point of need. It is hoped that this will be positively reflected in the on-going evaluation process.

It is important for the purpose of this report to focus on some activities and outcomes of the workers, to this end a series of key metrics are presented in sections 4-12. All of the activities and outcomes listed are referenced to the project's themes and objectives.

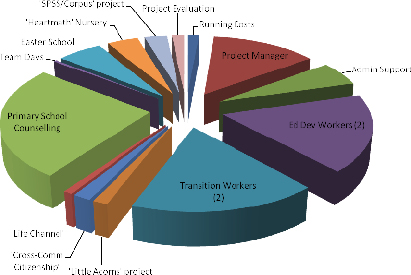

The diagram below summarises the distribution of actual project costs for the financial year. Further detail on this spend, including actual costs, is available at Appendix 1, however a number of key points can be highlighted here. Firstly, the total budget allocated to the FSCN was £350,000 for the year to 31 March 2010, and the project board has reported a small overspend of just under 1%. Secondly, it is clear from the diagram that our key areas of spend were in primary school counselling and in the provision of educational development and transition workers, the need for which had been previously identified through the Extended Schools clusters and other action plans in the local area. Thirdly, in addition to these key areas of spend the board was able to respond to identified needs and fund additional projects, including 'Heartmath' and 'SPSS/Corpus'. It should be noted that all salary costs are inclusive of all contributions.

Project Themes 1,2,4,5 Objectives 4,5,7

The aims of the transition workers are to engage young people, families and statutory, voluntary and community organisations in a co-operative and collaborative way to support the successful social and emotional transition from pre-nursery to nursery school, nursery school to primary school, and primary school to post-primary school.

| Sub-Project | Activities and Outcomes to 31 March 2010 |

|---|---|

| Transition Work in Greater Falls | |

| Early Years Programme in Greater Falls Extended Schools Cluster | 208 children received 4 sessions (in 2 nurseries and 1 primary school) 208 families received the resource pack 10 families were involved in group work |

| Using Home as a Learning Environment | Contact with 208 families, presentation and follow-up |

| Moving to Big School: Drama/Music Workshops | 208 children participated |

| Individual 1:1 support for pupils | 6 children involved |

| P7 Transition Drama Workshops | 6 primary schools, 255 children participated |

| P7 Transition Targeted Group Work | 35 children took part |

| Post-Primary Transition Group Work | 50 young people participated |

| Transition Mentor Group | Contact time with 25 young people |

| Training: Learning and Teaching Styles, Self-motivation, Motivating Children & Working Creatively with Children | 26 classroom assistants and other school support staff took part |

| Transition Work in Upper Springfield and Whiterock | |

| P7 Transition Work | 207 children participated |

| P7 Transition Group Work | Contact time with 7 children |

| Nursery Work with Parents | 16 parents received 4 x 2 hr sessions |

| Primary Parents: Motivating Children, Homework Routines and Reducing Stress | 16 parents participated |

| Individual Parents' Support in Transition Issues | 8 parents took part, across 4 schools |

Project Themes 1,2,3,4 Objectives 4,7

The educational development workers support the educational development of children, young people and their families within the Greater Falls and Upper Springfield areas of West Belfast. Their work is often varied due to the nature of the differing needs identified in the process of this work.

| Sub-Project | Activities and Outcomes to 31 March 2010 |

|---|---|

| Greater Falls Extended Schools Cluster | |

| Work with individual children and families with specific learning difficulties | Contact with 7 children |

| Group work with children, language and literacy support, speech development and behaviour support | 92 children participated, across 7 groups |

| Work with families in the home on specific needs | 13 families took part |

| Parent Groups | 36 families, in 5 groups, took part |

| Workshops in reading, talking and listening | 75 children in 3 groups x 4 sessions |

| 'Achieving Beechmount'multi-disciplinary group | Monthly meetings and follow-up activities |

| Upper Springfield and Whiterock Extended Schools Cluster | |

| Group work with children on a range of needs as agreed with the school | 7 primary schools involved, 23 groups and 160 children |

| Work with families including home visits | 5 families, in addition to 3 parent groups involving 17 parents |

| Work with individual children on specific learning difficulties | 3 children |

| P3 Talking and Listening | 20 children, 1 school over 4 sessions |

| Nursery storytelling workshops | 20 parents participated |

| Linguistic phonics | 21 attendees including parents and community |

All of the above contacts are documented and recorded and are available from the team manager on request.

Project Themes 1,2,3,4,5 Objectives 2,3,5,6,7

The parents' groups of Harmony Primary School, Glencairn, and St. Paul's Primary School, Beechmount set out to undertake a cross-community leadership programme. The aims include developing cross-community and interdenominational links; promoting tolerance and acceptance of diversity and promoting political reconciliation between the parents' groups. Local politicians from Belfast City Council, the Northern Ireland Executive and Dail Eireann took part in the programme. Five parents from St. Paul's Primary School and three parents from Harmony Primary School have been involved in this project.

Project Themes 1,3,6 Objectives 4,6,8

The FSCN has become a partner in the delivery of the long-established Easter School, an organised revision course for approximately two hundred young people across West Belfast, with the aim of improving on the predicted grades of students not expected to attain higher grades at GCSE.

Project Themes 1,3,5 Objectives 5,6

Three large television screens have been placed in public areas of Corpus Christi College providing information on the promotion of health and well-being and other school events. It is expected that students will see at least one of the screens each day, with the aim of improving pupils' knowledge and understanding of health-related issues.

Project Themes 2,3,4,5,6 Objectives 2,3,5,6,7,8

An invitation was extended to the project managers of various services coming into the area to meet and share information. Outcomes of the day included:

Project Themes 1,3,4,5 Objectives 4,5,6,7,8

Primary school counselling provides individual and group counselling to children in their own school. The counsellors also work with parents, carers and teachers to help everyone understand the child's feelings and behaviour and to support the child in developing effective ways of coping. Together, these different aspects of work help provide a counselling service that is child-centred, context-focussed and based on the strengths of the child and their caring family/school contexts. This service was commissioned through tender, and is delivered by Barnardo's NI.

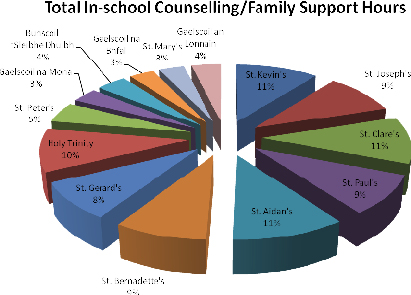

The diagram below represents the total number of hours of in-school counselling and family support in percentage values by school. Details of these percentage and absolute values for the year 2009/10 are available at Appendix 2.

In the second quarter of the year a predicted underspend was identified. The project board approved a proposal to use the money to promote the following initiatives.

Project Themes 1,3,4,5 Objectives 2,3,4,5,6,7

The personal development programme for pupils of the college was aimed at augmenting the service provided by the BELB Secondary Pupil Support Service (SPSS) available to the post-primary schools. Concern was raised at the 'Achieving Beechmount' cluster that a growing number of pupils would not receive the support they required which would, as a consequence, create more serious problems for the children and their families.

It was proposed to the SPSS and the school that the FSCN would support the training of a teacher and a classroom assistant to support the SPSS service presently in the school. Before the programme began, SPSS were working with 12 pupils and had a waiting list of 19 pupils. Since the introduction of the programme, which included a Youth Intervention Worker at no cost to the FSCN, a total of 60 pupils have received a minimum of 6 sessions each. The role of the FSCN was to initiate the project, provide 'pump-priming' funds and step back from the process. A key outcome is that the school has decided to continue the service in the next academic year at its own expense.

Project Themes 1,2,3,4 Objectives 2,4,5,7

Following the successful introduction of this initiative into local primary schools in the Extended Schools clusters of Upper Springfield and Greater Falls, it was decided to extend the programme into local nurseries and community groups. The programme uses the innovative 'journey to my safe place' to help reduce stress; raise academic performance and improve classroom behaviour.

In total 27 schools and 6 community organisations have participated in the programme, while 144 members of staff have received training in its delivery. By the end of March 2010, 1800 children and young people in both clusters were practising the 'journey to their safe place' on a regular basis. An evaluation report for 2008-09 of the work in the Greater Falls is available on request.

The role of the FSCN was again to identify the gap and bring service to the point of need. There is no recurrent expenditure in the 2010-11 budget.

The programme of evaluation commenced during 2009/10 following a tendering process managed by the project board and the procurement section of the BELB. FGS McClure Watters were successful in bidding and the process began in November 2009. The team of evaluators provided the project board with a Project Initiation Document in December 2009 and followed this up with an update on the 8th June 2010. An interim report is due at the end of June with a final draft report scheduled for the end of December 2010. Consultation with partners and stakeholders is on-going.

In January 2010 the project board approved planning for a conference in association with Barnardo's NI. The aims of the conference were:

a) To demonstrate the importance and impact of DE policy coherence.

b) To showcase the work of the FSCN workers and the role of Barnardo's NI and other partners in this work.

c) To demonstrate the impact of early intervention on children, young people and families in the area around Corpus Christi College.

d) To provide information on the full range of on-going collaborative activities and signpost other projects being planned.

e) To provide those present with an opportunity to consider and comment on the evidence presented.

The conference was subsequently held on 13th May 2010 at the Beechlawn Hotel Belfast. The project board was delighted to welcome Minister Caitriona Ruane and thanked her for her very supportive comments when opening the conference. Other speakers at the conference included Linda McClure, Director of Operations, Barnardo's NI, who addressed delegates on the 'Power of Partnership'. Although officially 110 delegates attended, informal headcounts on the day put the number at approximately 140. Each delegate was provided with a pack of information (available on the website www.fscn.co.uk) and greeted by a 'village' of information stalls manned by 16 service providers.

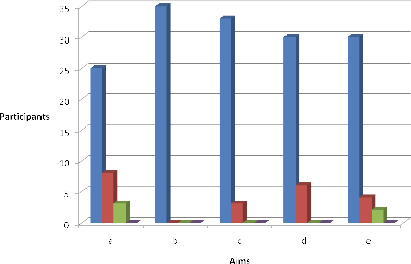

Participants at the conference were asked to consider the extent to which the conference met the above stated aims. Participants could score the aims from 1 to 4, with 1 indicating high achievement and 4 indicating low achievement. In all 36 evaluation forms were returned, and the results are summarised below:

As can be seen in the above diagram, conference participants were in strong agreement that the aims of the conference had been met. Moreover, delegates were also generous in their praise in additional comments on their returned forms, and these comments are available at Appendix 3.

The table below shows actual spend for the period 01 April 2009 – 31 March 2010, summed and compared to budget. These values correspond to the distribution of spend, summarised in Diagram 1.

| Actual Spend to 31 March 2010 | Cost £ |

|---|---|

| Running Costs | 5,000 |

| Primary School Counselling | 90,014 |

| Educational Development Workers (2) | 62,343 |

| Transition Workers (2) | 62,343 |

| 'Little Acorns' project | 5,000 |

| 'Cross-Community Citizenship' | 6,000 |

| 'Life Channel' | 3,000 |

| Team Days | 1,500 |

| Easter School | 20,000 |

| Project Manager | 47,500 |

| Administrative Support | 19,992 |

| 'Heartmath' Nursery | 14,000 |

| 'SPSS/Corpus' project | 10,000 |

| Project Evaluation | 6,000 |

| Total Spend 2009/10 | 352,692 |

| Budget as approved by DE | 350,000 |

| Overspend 2009/10 | 2,692 |

Activity Summary: Time 4 Me, April 2009 - March 2010

The table below represents the total number of hours of in-school counselling and family support in absolute and percentage values, as summarised in Diagram 2.

| Name of School | Total In-school Counselling/ Family Support Hours | As a Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| St. Kevin's | 131.5 |

10.66% |

| St. Joseph's | 116.5 |

9.44% |

| St. Clare's | 132 |

10.70% |

| St. Paul's | 112.5 |

9.12% |

| St. Aidan's | 131 |

10.62% |

| St. Bernadette's | 107 |

8.67% |

| St. Gerard's | 106 |

8.59% |

| Holy Trinity | 121 |

9.81% |

| St. Peter's | 59.5 |

4.82% |

| Gaelscoil na Mona | 41 |

3.32% |

| Bunscoil tSleibhe Dhuibh | 48 |

3.89% |

| Gaelscoil na Bhfal | 40 |

3.24% |

| St. Mary's | 40 |

3.24% |

| Gaelscoil an Lonnain | 48 |

3.89% |

1234 |

100.00% |

2009-2010

The Belfast Boys' Model and the Belfast Model School for Girls serve communities in North and West Belfast which have suffered more than most during the last 30 years. There exists within the area, some of the most disadvantaged wards in Northern Ireland and such high levels of social deprivation and disadvantage present a challenging environment in which to deliver "achievement for all".

Those involved in leading, delivering and supporting education in the city agree that high quality educational achievement for all pupils is dependent upon high quality teaching and learning within the classroom, coupled with high quality support beyond the classroom.

The Full Service Schools' Project provides such holistic support to young people in the pursuit of raising levels of achievement for all. This report outlines the range of services and activities provided during and beyond the school day which:

The emphasis of the project is on outcomes; challenging targets are set together with established benchmarks for measuring success. An evidence based approach has been adopted where programmes and activities are developed in the light of identified need.

Much of the success highlighted in this report is due to the leadership of the principals of both schools, allied to the hard work and dedication of staff and co-ordinators in both schools.

The report presents clear evidence that the Full Service Schools' Project is achieving its objectives and disadvantage and underachievement are being tackled in a pro-active way. It is vital that policy makers continue to support and sustain this approach.

Chief Executive

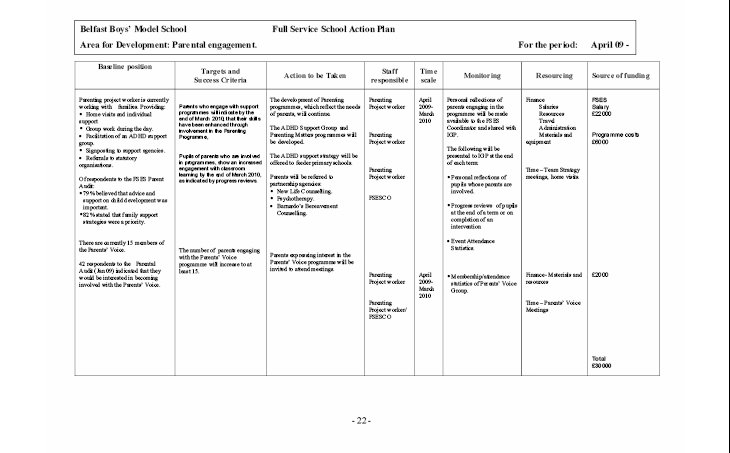

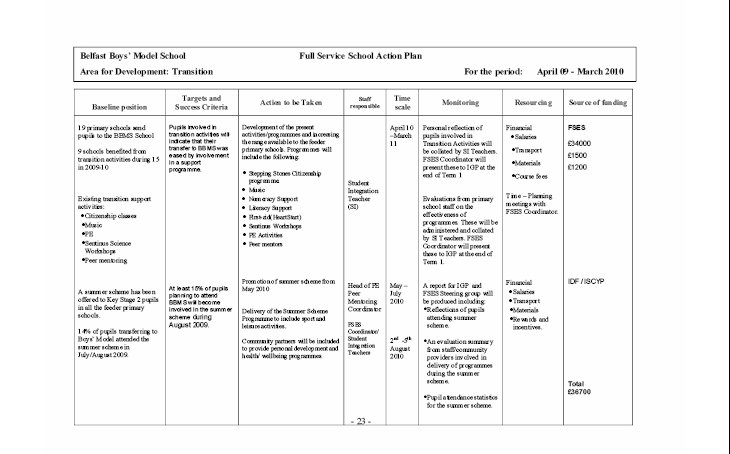

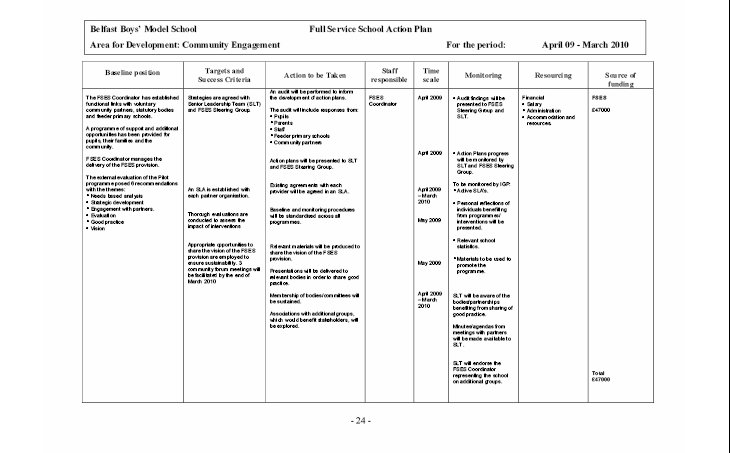

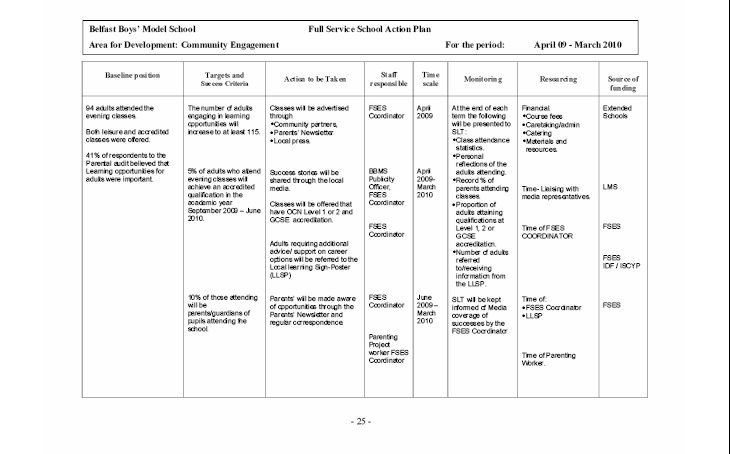

Full Service Extended School Programme

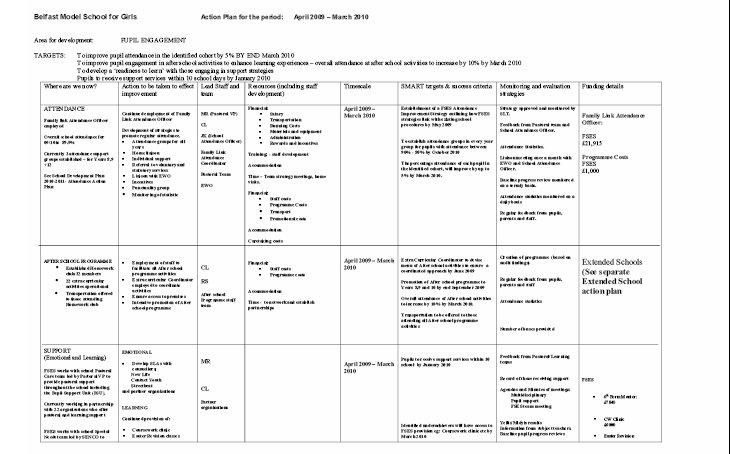

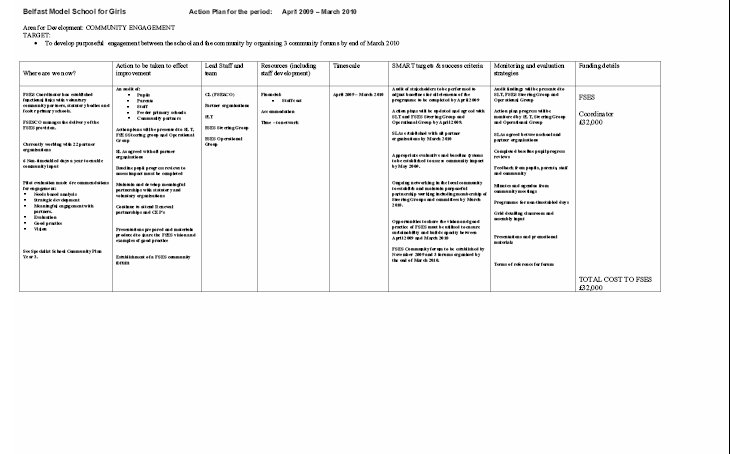

The Full Service Extended School project was initiated in the Belfast Boys' Model and Belfast Model School For Girls in September/October 2006. The purpose was to provide a programme which would integrate services by bringing together professionals for the provision of education, family support, health and other community services. The over-arching target was to raise performance in these Full Service Schools and in feeder primary schools.

The development of the FSES auditing process and the project action plans were informed by the following policies:

A Full Service school focuses on the needs of the whole child – physical, emotional, social and academic – to create the conditions necessary for all children to learn. It is open to young people, families and community members before, during and after school, all year-round. Full Service Schools strive to strengthen families and communities so they are better equipped to support young people.

A comprehensive audit was conducted by the coordinators to ensure that partnerships and initiatives were established to meet the needs of all stakeholders and these were fully integrated into the School Development Plan. With support from the coordinator, families, students, teachers, principals, community residents and partner organisations, decisions are made together to foster a culture of learning and personal development. School and community work together to help young people address barriers to success and reach their potential.

Each Full Service programme will have discrete differences determined by the needs of the community. Some of the responses to these needs include:-

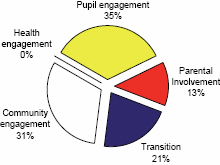

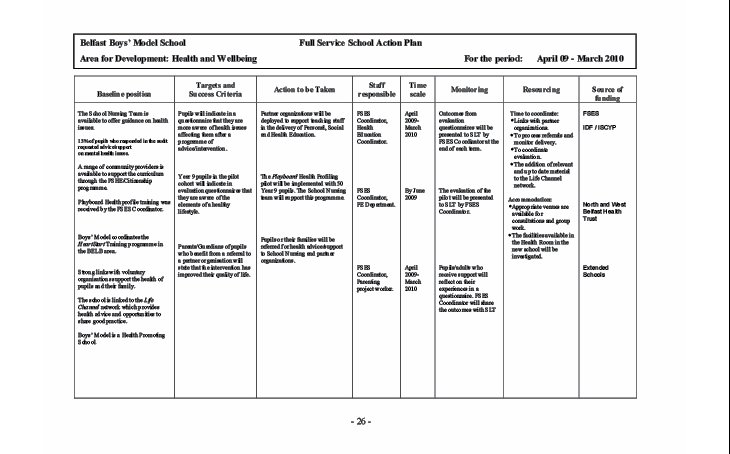

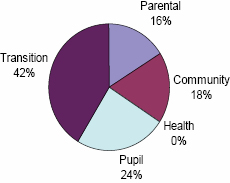

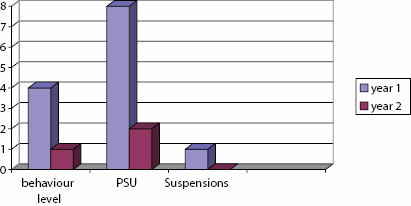

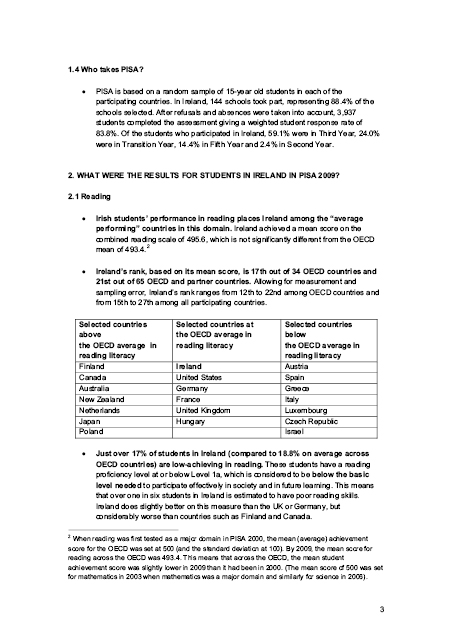

The total Full Service budget allocation for Belfast Boys' Model School for the year ending 31st March 2010, was £175k. The chart above indicates that the majority of resources were allocated to strategies promoting Pupil and Community Engagement.