Session 2009/2010

First Report

COMMITTEE FOR HEALTH, SOCIAL SERVICES AND PUBLIC SAFETY

Inquiry into Obesity

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the committee,

minutes of evidence and written Evidence relating to the report

Ordered by the Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

to be printed 1 October 2009

Report: 10/09/10R (Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

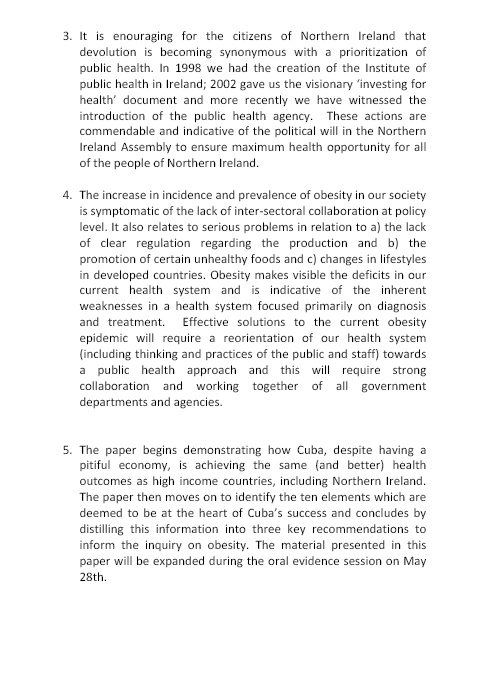

For more information please contact the

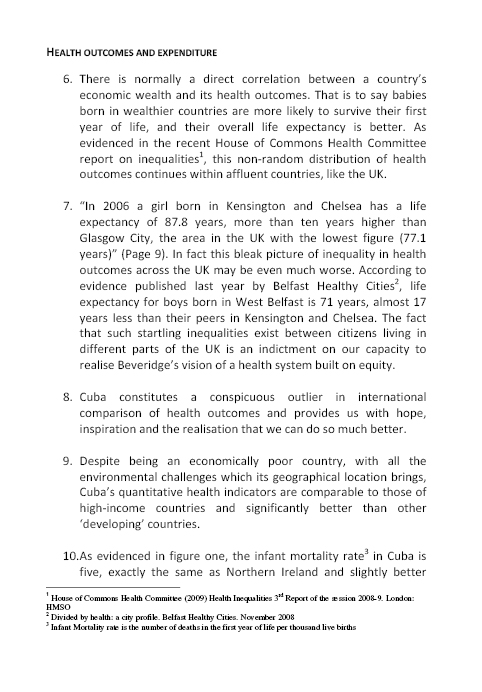

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

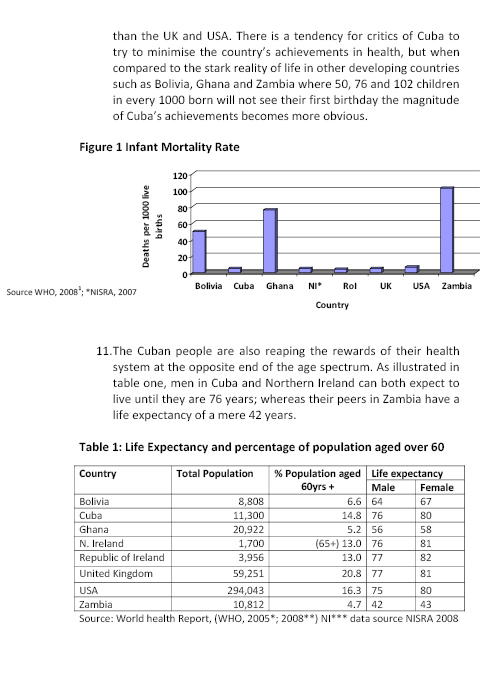

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Committee Powers and Membership

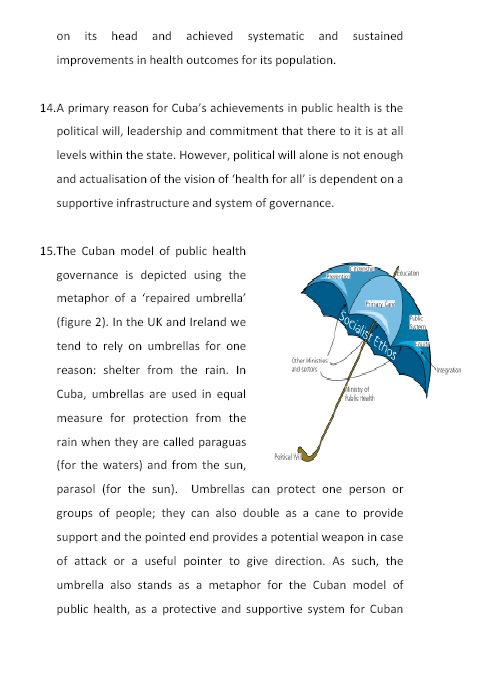

The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 46.

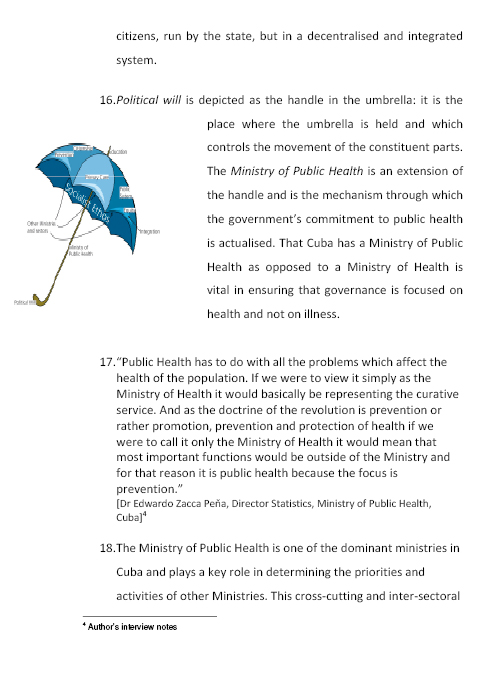

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Consider relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of primary legislation;

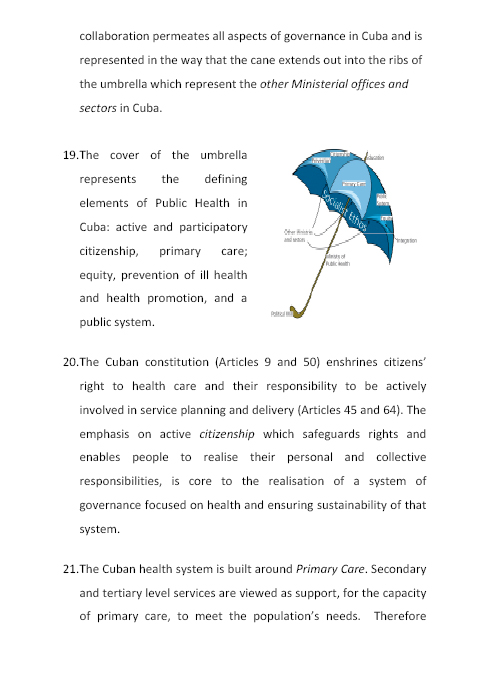

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on any matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee is as follows:

Mr Jim Wells4 (Chairperson)

Mrs Michelle O’Neill (Deputy Chairperson)

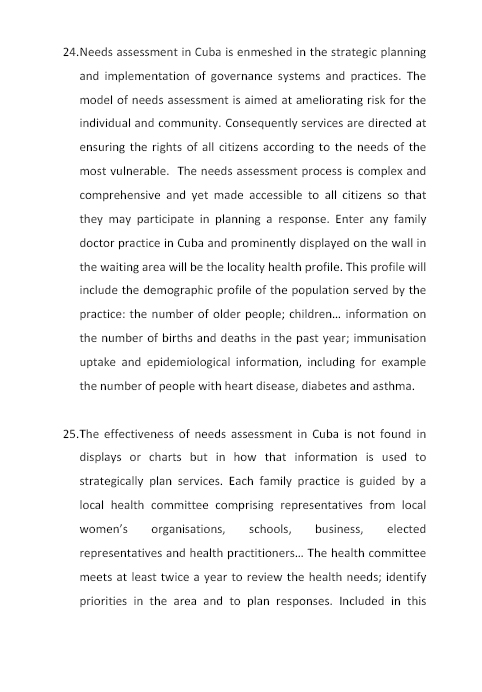

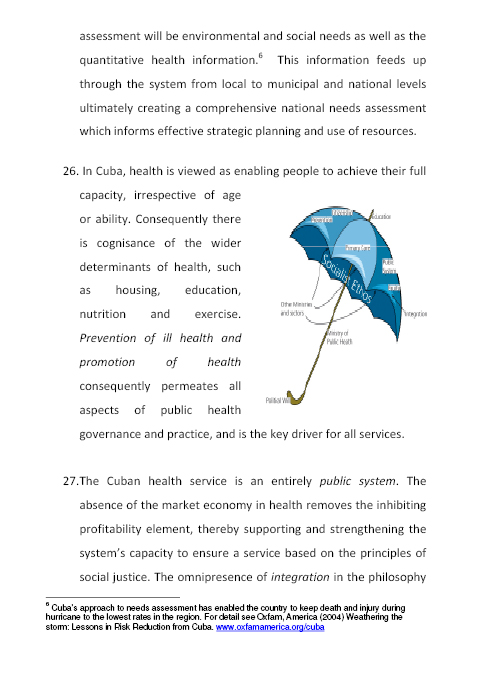

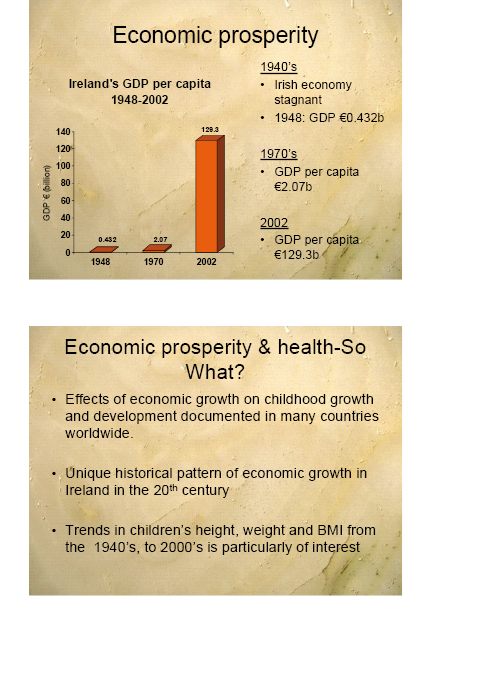

Mrs Carmel Hanna Dr Kieran Deeny

Mr Alex Easton Mrs Claire McGill1

Mrs Dolores Kelly3 Ms Sue Ramsey

Mr Sam Gardiner2 Mrs Iris Robinson MP5

Mr John McCallister

1 with effect from 20 May 2008 Mrs Claire McGill replaced Ms Carál Ní Chuilín.

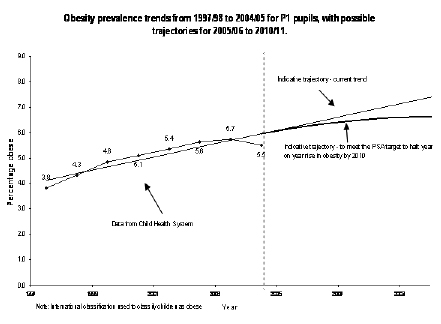

2 with effect from 15 September 2008 Mr Sam Gardiner replaced Rev Dr Robert Coulter.

3 with effect from 29 June 2009 Mrs Dolores Kelly replaced Mr Tommy Gallagher

4 with effect from 4 July 2009 Mr Jim Wells replaced Mrs Iris Robinson

5 with effect from 23 September 2009 Mrs Iris Robinson replaced Mr Thomas Buchanan

Table of Contents

Volume 1

1. Introduction

2. Background

Health Implications

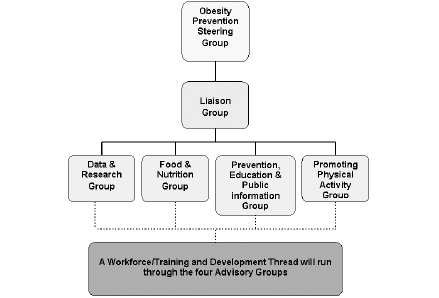

Cost of Obesity

Measuring Obesity (BMI)

Causes of Obesity

3. Trends

A Major Global Health Problem

Obesity Prevalence in the UK and ROI

Obesity Prevalence in Northern Ireland

4. Current Approach

Targets

Funding

Life Course Approach

Leadership

Co-ordinated Approach

Existing Initiatives

5. Weight Management

Primary Care

Secondary Care

Bariatric Services

6. Diet and Exercise

Healthy Eating

Food Labelling

Food Portion Sizes

Mixed Messages

Exercise

7. Role of Other Departments, Bodies and Sectors

Role of Local Authorities

Role of the Media

8. Obesogenic Environment

9. Other Issues

Health Inequalities

Community Approach

Workplace Health

Research

Data Collection

10. Conclusion

Appendix 1:Minutes of Proceedings 49

Appendix 2:Minutes of Evidence 73

Volume 2

Appendix 3:Written Evidence

Appendix 4:Other Evidence considered by the Committee

Appendix 5:Minutes of Evidence Session held on 19th May 2009 699

Appendix 6:List of Witnesses who gave Evidence to the Commitee 797

Executive Summary

Obesity is a major global public health problem. Recent decades have seen a significant rise in levels of overweight and obesity in many countries around the world. In a number of the major developed countries, including the UK and the USA, the rates of obesity have doubled in the last 25 years and this relentless increase is predicted to continue in the decade ahead. The most recent Health and Social Wellbeing Survey in Northern Ireland in 2005 found that 59% of all adults here were either overweight or obese, with 24% of adults obese. Worryingly, data from the Northern Ireland Child Health System in 2004/05 found that 22% of children are either overweight or obese, with more than 5% already obese.

The 2007 Foresight Report, a report complied by a panel of leading experts and commissioned by the UK Government, warned that if trends in overweight and obesity continue to rise, there is a real prospect that by 2050, ‘Britain could be a mainly obese society’. It predicted that by that date, 60% of men and 50% of women in the UK could be obese. The Department’s Investing for Health Strategy in 2002 had estimated that by 2010 the cost of obesity to the NI Economy could exceed £500m per annum.

Obesity has been variously described to us as a ‘well established epidemic’, a ‘tsunami’, a ‘crisis’ and a ‘population time bomb’. It is a problem that will have an enormous impact, not just on the health of the population, but something that threatens to engulf the entire health service and it will have a very serious impact on society and the economy. For many people obesity is seen primarily as a vanity or aesthetic issue. However, it has very serious and life-threatening health implications through a wide range of conditions, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, some forms of cancer, and high blood pressure. We were told that obesity could cause the present generation growing up to have a shorter life span than their parents.

In this report the Committee looked at both the current strategic approach to the prevention of obesity and the availability of weight management or other services to deal with obesity related ill health.

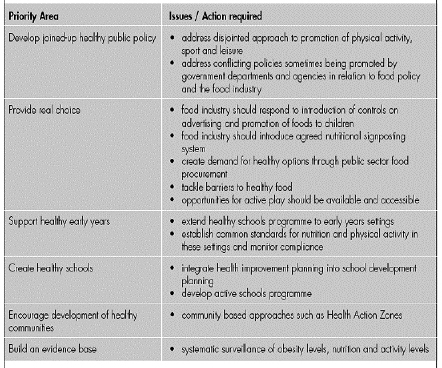

Prevention

To date, no country in the world has been able to develop an overall strategic approach that has significantly reduced obesity prevalence. However, the recent development of the Healthy Weight, Health Lives strategy in England, represents the first national population-wide strategy but it is too early yet to judge its effectiveness. It is clear that obesity levels have increased steadily over many years and it will take a long-term response to reverse this trend.

In Northern Ireland the Department of Health has moved away from the Fit Futures initiative, which focussed on tackling obesity in children and young people, and has begun to develop a whole life course approach, similar to the Healthy Weight, Health Lives strategy in England. While we support the development of the life course approach we have concerns that the Fit Futures initiative has not been formally signed off and implemented.

All Departments and sectors have a crucial role to play in tackling obesity and all need to be involved and committed to the development of the new life course strategy. We recommend that the strategy should be jointly led by the health and education Departments, as has happened in England. There must be single strong effective leadership to drive the strategy forward and, given the potential for significant cost benefits and the consequences of failure to invest, it needs to be provided with significant resources.

Most Departments outlined the action they currently undertake relating to obesity. As identified in the Fit Futures initiative the importance of working with children and young people on nutrition and exercise cannot be over emphasised. The Department of Education has a particularly crucial role in this and, while we welcome the action being taken on nutrition in schools, we call on that Department to make PE in schools compulsory and subject to regular monitoring.

We recognise the potential for the draft 10 year Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation in Northern Ireland, developed by the Department for Culture, Arts and Leisure in 2007/08, to contribute to a reduction in obesity and we call for it to be resourced and implemented without further delay.

While the cause of obesity can be described in simple terms as an imbalance between the amount we eat and the level of exercise we undertake it cannot be solved by individuals alone. There are many and varied environmental factors, from the accessibility and marketing of food, to transport, planning and other issues that dissuade a healthy diet and physical exercise and these must be tackled. Referred to as the ‘obesogenic environment’, its influence and impact is not widely understood or adequately addressed.

Other issues dealt with in the report include, the role of the new Public Health Agency, the role of local authorities, the potentially positive and negative roles of the media, as well as the need for a community approach and the need to tackle health inequalities. We also identify the need for better co-ordinated research and more representative and reliable data collection.

Weight Management Services

We are very concerned to learn about the current levels of obesity related ill health throughout Northern Ireland and particularly by the number of severely obese patients for whom lifestyle and drugs have failed. These patients now face the prospect of bariatric surgery and the subsequent need for lifelong medical follow-up treatment. We are gravely concerned at the dearth of services at primary and secondary level to deal with those who have serious medical conditions related to severe obesity and the absence of any services to prevent further weight gain in patients with lower degrees of overweight.

We witnessed the frustration of frontline clinicians who told us that services designed to address specific clinical conditions, such as diabetes, cannot adequately address the needs of obese patients. The absence of effective interventions for children with obesity was also highlighted to the Committee.

It is estimated that as many as 50,000 people in Northern Ireland may be eligible for bariatric surgery and this service is currently not provided within Northern Ireland. Last year around 80 people were referred for bariatric surgery to Great Britain. It has been estimated that the cost of treating just 1,000 patients and providing the necessary medical follow-up could be around £10 -£15 million.

On the positive side we recognise that small weight losses do produce health gains and research shows that even a modest reduction in weight of 10% can have a significant impact on a patient’s health. Further delay in providing a comprehensive range of appropriate weight management services will result in greater long term costs. An urgent review to develop such a range of services must be undertaken now.

Summary of Recommendations

1. Obesity is the most serious and most challenging public health issue that we face at this time and it is also one of the most complex. There is therefore an urgent need to develop and implement a comprehensive and robust strategy to address the issue. (Paragraph 49)

2. We share the deep concern of those who expressed regret that the Fit Futures Implementation Plan has not been formally signed off and implemented. The failure to do so has, we believe, created uncertainty and a potential hiatus until a full strategy is in place. (Paragraph 50)

3. We welcome and support the plans by the Department to develop a life course strategy however we fully recognise that tackling obesity effectively is not solely a matter for the health service. We note that the Fit Futures Report contained a joint target with the Departments of Education and Culture, Arts and Leisure. We strongly recommend that the new life course strategy be developed jointly in partnership with other departments, particularly the Department of Education, as has happened in England. (Paragraph 51)

4. Growing levels of obesity will continue to generate enormous costs to society, particularly the health and social care sector in the years ahead. Given this and the potential for significant cost benefits, we belief it is imperative that substantial and sustained resources are provided to implement the new life course strategy. We would urge that this funding be ring-fenced for at least the first phase of implementation (3-5 yrs) to ensure that it is not impacted by other acute and emerging priorities.(Paragraph 52)

5. It is very clear that single strong effective leadership is crucial in tackling obesity but the exact locus of that leadership has been the subject of debate. We recommend that the question of who provides overall leadership be considered in depth during the development of the Life Course Strategy and widely consulted upon before reaching a decision. (Paragraphs 57-58)

6. We recognise that the establishment of the new Public Health Agency provides a unique opportunity to develop a joined-up approach across all Government Departments, public sector agencies including local authorities, the private sector, and the voluntary and community sectors to tackle obesity. We advocate that the Agency make this issue a top priority and we urge all departments to play their part in delivering a concerted long-term response. (Paragraph 62)

7. We recommend that the Department commission an urgent audit of existing obesity-related initiatives so that the need for evaluation or further research can be identified and examples of good practice can be rolled out more widely. We recommend that the Public Health Agency, perhaps in conjunction with the planned All-island Obesity Observatory, develops and maintains a central data base of projects and develops standardised evaluation tool kits. (Paragraph 70)

8. We recommend that the Department, in conjunction with the Health and Social Care Board, develops a range of evidence-based referral options for use by primary care practitioners. (Paragraph 82)

9. We urge the Minister to exert influence at a national level to introduce the allocation of Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) points for positive obesity management rather than simply for maintaining a register of obese patients. (Paragraph 83)

10. We call on the Minister, as a matter of urgency, to undertake a comprehensive review of weight management services at all levels for adults and children. The review must address the need for dedicated obesity clinics and a separate bariatric service for Northern Ireland, including the provision of bariatric surgery and the lifelong medical follow-up for individuals required following such surgery. The review should also consider the merits of adopting examples of good practice from elsewhere, such as the Counterweight programme in Scotland and the Carnegie Weight Management programme in England. (Paragraph 100)

11. We urge the Department and the Food Standards Agency to continue to work with manufacturers and to exert pressure at a national and European level to introduce regulatory controls on the levels of salt and saturated fat in manufactured foods. (Paragraph 108)

12. We fully support the calls for a single, consistent food labelling scheme using the traffic light system and urge the Minister and the Food Standard Agency Northern Ireland to consider whether such a system could be made mandatory on all food retail products. We also call for more action to enforce a similar clear and simple nutrition labelling system at non-retail outlets, such as restaurants and catering establishments. (Paragraph 114)

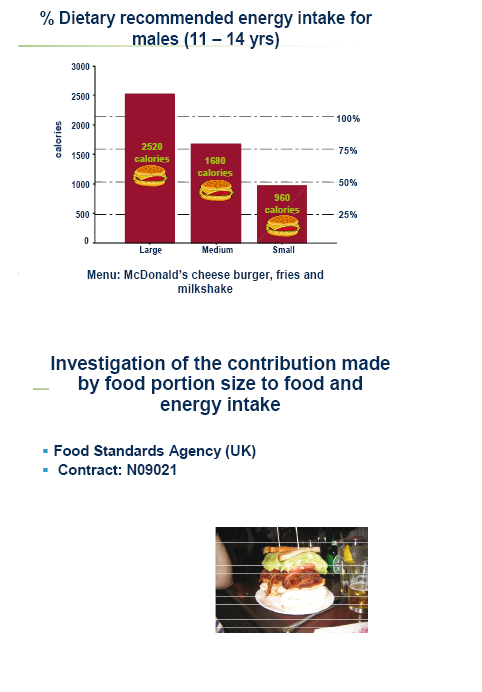

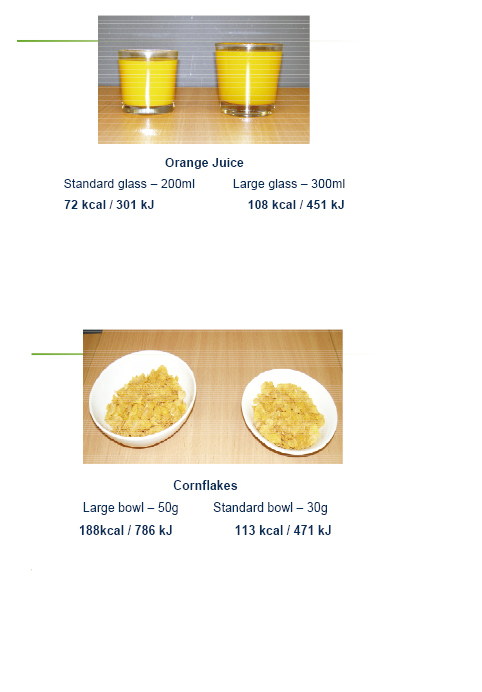

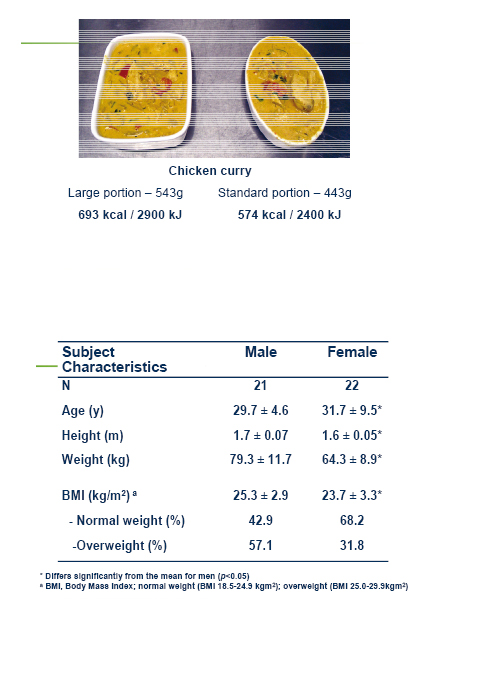

13. While recognising the difficulty in regulating food portion sizes in catering and similar settings, we urge the Department and the Food Standards Agency Northern Ireland to examine how issues like food promotion and pricing impact on portion sizes and how they might be influenced. (Paragraph 118)

14. We believe there is confusion over what exactly constitutes ‘five portions of fruit and vegetables a day’ and particularly around the size and content of a portion. We urge the Public Health Agency to examine how greater clarity and understanding about this health message, and how it might impact on levels of obesity, can be achieved. (Paragraph 120)

15. We call on the Executive to ensure that the Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation in Northern Ireland is properly resourced and implemented without further delay and that this work dovetails with the development of the life course obesity strategy. (Paragraph 128)

16. We urge each and every Department to recognise that they have a crucial role to play in responding to the obesity epidemic either through direct action or through policies and practices that impact on the obesogenic environment. (Paragraph 135)

17. We call on the Department of Education to make at least 2 hours of PE in schools compulsory and subject to regular monitoring by the Educational and Training Inspectorate. (Paragraph 142)

18. We urge the full involvement of local councils in developing the new life course strategy. (Paragraph 147)

19. We urge the Minister to work with colleagues throughout the UK to explore the feasibility of banning the advertising of food and drink products that are high in fat, salt or sugar before the 9 pm watershed. (Paragraph 152)

20. We call on the Minister to develop a comprehensive media approach as part of the life course strategy and to consider, for example, how new and emerging media such as text and Twitter could be used to engage with young people. (Paragraph 153)

21. We call on the Executive to fully recognise the potential impact of the obesogenic environment on the health and wellbeing of the population and to consider the merits of introducing a system whereby the impact of all major policy decisions are subject to an obesity proofing exercise. (Paragraph 162)

22. In developing the Life Course Approach we urge the Department to take account of health inequalities and particularly the need to address the higher levels of obesity in areas of social deprivation. (Paragraph 171)

23. We recognise the benefits for both employers and employees of promoting healthy lifestyles in the workplace and we urge all employers to consider initiatives that promote healthy eating and greater levels of exercise in the workplace. (Paragraph 176)

24. We urge the Department to examine how data collection can be improved through reform and better funding of the Child Health System. This should facilitate extending BMI measurements beyond Primary One children. Enhanced funding should also facilitate better collection of adult data based on actual BMI measurements rather than self-reporting. (Paragraph 187)

Introduction

1. Obesity is a complex condition which poses a serious threat to health and well-being on a global scale and, to date, no country in the world has been able to develop an effective overall approach to successfully address the issue. The Committee is conscious that within Northern Ireland around 60% of the adult population and 25% of children are either overweight or obese and this is predicted to grow significantly over coming years. The Committee recognises that action must be taken now to prevent the cost to the health service and to society generally from escalating out of control.

2. This report sets out the results of the Committee examination of the current strategic approach to tackling obesity and its impact on health and well-being. In particular the Committee has looked at:

- the scope and appropriateness of the current approach to the prevention of obesity and the promotion of lifestyle change;

- the availability of weight management or other intervention services to tackle obesity related ill health; and

- what further action is required, taking account, of the potential to learn from experience elsewhere.

3. The Committee invited written submissions from a wide range of organisations and groups both within Northern Ireland and further afield and placed notices in the main newspapers. As with many public health issues the Committee recognised that tackling obesity is not just a matter for the health Department and, accordingly invited views from all Departments and Assembly Statutory Committees. The Committee took formal evidence from seventeen separate organisations over a four month period from February to June 2009. Recognising the importance of research into methods of tackling obesity and the need to incorporate that research into policy and practice, the Committee organised a Research Round-Table Event in Parliament Buildings involving a number of eminent academic experts in the field from throughout the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland and a small number of key stakeholders.

4. We are grateful to all those who helped us with this Inquiry, including those who provided oral or written evidence and those who participated in the Research Event. We are particularly grateful to those from outside Northern Ireland who came and shared their expertise and experience with us.

Background

Health Implications

5. The Department defined obesity as “a condition where weight gain has got to the point that it poses a serious threat to health".[1] The severity of that risk to health from being overweight or obese does not appear to be widely recognised or understood. The Executive Director of the Northern Ireland Food and Drink Association reminded the Committee that only 6% of people understand the risks of being overweight. He said “Obesity is seen as a vanity rather than a health issue, and we must change that mindset".[2] The British Medical Association put it very starkly saying that obesity “is a population time bomb that will, perhaps, cause the generation growing up to have a shorter lifespan than their parents".[3] The Public Health Agency pointed to recent studies which “suggest that the risk of premature death in people with obesity is similar to that seen in people who smoke more than 10 cigarettes a day. Obesity is therefore not an aesthetic issue – it shortens life and increase the risk of a range of conditions".[4]

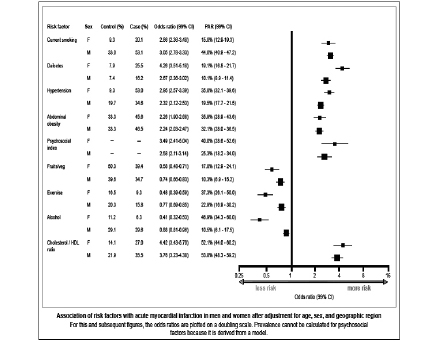

6. The Department in its evidence listed ten serious conditions associated with obesity and added that, “evidence also indicates that obesity can reduce life expectancy by approximately 9 years; and can impact on emotional/psychological well-being and self-esteem, especially among young people."[5] The British Medical Association listed the four most common health problems associated with obesity as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthritis.[6]

7. The British Heart Foundation Northern Ireland pointed out that, “heart and circulatory disease is Northern Ireland’s biggest killer – responsible for more than one in three deaths each year"[7]. The Foundation stated that, “obesity is, in itself, an independent risk factor for heart disease, but it can also be seen as an accumulator, in that it has an effect on other risk factors including diabetes and hypertension, which is also linked to stroke".[8] The British Heart Foundation Northern Ireland referred to the INTERHEART study which estimated that 63% of heart attacks in Western Europe are caused by abdominal obesity[9].

8. Mr Iain Foster, Diabetes UK, explained the impact of obesity as a significant factor in the number of those suffering from type 2 diabetes in Northern Ireland. He stressed the importance of getting beyond the misconception that diabetes is a mild condition. He said, “It is not mild; it is a chronic condition that has no cure. Type 1 diabetes will take up to 20 years off a person’s life expectancy. Type 2 diabetes will take up to 10 years off a person’s life expectancy." Mr Foster stressed that while obesity has no connection to type 1 diabetes “weight contributes to around 80% of cases of type 2 diabetes".[10] Dr Michael Ryan, a frontline clinician, estimated that “about 90% of the patients that attend my diabetes clinics have weight-related issues". Dr Naresh Chada, DHSSPS, pointed out that 65,000 to 70,000 people suffer from type 2 diabetes and said that, “if we do not halt the year-on-year increase in obesity, we could have another 10,000 to 15,000 people with diabetes in Northern Ireland by the early to middle part of the next decade."[11]

9. A Report by the Northern Ireland Audit Office into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes in Northern Ireland[12] confirms that weight gain is a major influence on the prevalence of type 2 diabetes which is the most common form of diabetes. The Report also highlighted the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in younger people, partly due to lifestyle factors such as diet, lack of physical activity and obesity. This supports the statement by Dr Ryan who said that, “When I was training, type 2 diabetes was called ‘maturity-onset diabetes’. Nowadays, I see 18 and 19-year-old people with that condition, and paediatricians are seeing it in the under 16s. That was unheard of."[13] The Health Minister, in a debate in the Assembly on diabetes, acknowledged that, “the Health Service as we know it will be overwhelmed in twenty years time if we do not tackle diabetes, obesity, and lifestyle. Hospitals are filled with people, who, had they made different lifestyle choices 20 or 30 years ago, would not be there."[14]

10. The link between obesity and cancer is perhaps not so widely recognised. However, Dr Chada, DHSSPS, warned that, “Cancer — particularly gynaecological cancers — are also associated with obesity. I refer to cancer of the uterus, cervix and ovary. Men may be affected by bowel and prostate cancer. A certain proportion of cancers can be attributed to obesity."[15] Action Cancer highlighted that, “two thirds of cancer can be prevented through lifestyle changes, such as more exercise and a change in eating habits"[16] while the British Medical Association pointed out that “obesity increases the likelihood of developing cancers such as breast, colon, endometrial, oesophageal, kidney and prostate cancer by up to 33%"[17].

11. The Royal College of Psychiatrists argued that, “people with mental illness and those with learning disabilities are more likely than the general population to be obese, to have physical health problems arising from this, and to have difficulty managing weight." The Royal College suggested that the reasons for this are complex and could include living in an area of social deprivation, inactivity, medication factors, emotional eating, as well as a reluctance of medical practitioners “to raise the issue of weight with a person who is already vulnerable"[18]. The Belfast Health and Social Care Trust Physiotherapy Service agreed that, “people with mental illness are predisposed to the development of obesity by the nature of their illness; the situation is however made worse by the fact that the medication prescribed for the treatment of their condition does in fact further increase their likelihood of developing obesity".[19]

12. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy suggested that, “The incidence of falls is another factor that has an impact… an obese person’s muscles become weaker — their muscle tone lessens and their balance reduces; therefore, the risk of falls or of osteoporosis from not doing weight-bearing exercises is increased."[20]

13. Nevertheless, the British Medical Association and others stressed to the Committee “there is nothing about this problem that is inevitable"[21]. Dr Ryan agreed, saying that, “The impact of obesity and overweight is worse than all the cancers put together, on an epidemiological basis, and yet we can intervene, and it can be prevented if caught early enough."[22] In his written evidence Dr Ryan stated that, “there is incontrovertible evidence that weight reduction, however achieved, is effective in reducing morbidity and prolonging life".[23] The Belfast Health and Social Care Trust Physiotherapy Service referred to the Crest Guidelines which “highlight the fact that even a 10% reduction in weight can induce up to a 50% reduction in obesity related cancer deaths, up to a 50% reduction in the development of diabetes as well as having a significant positive impact on lowering blood pressure and cholesterol levels."[24]

Cost of Obesity

14. In addition to the serious health implications for individuals, policymakers are increasingly concerned that the growing obesity problem will place a substantial financial burden on their respective health finances. This is particularl y pertinent within the four universal, tax-funded health systems of the NHS. According to the 2007 Foresight Report in the United Kingdom “by 2050, 60 per cent of males and 50 per cent of females could be obese, adding £5.5 billion to the annual cost of the NHS, with wider costs to society and business estimated at £49.9 billion."[25]

15. Many of the submissions to the Inquiry pointed to the enormous social and economic costs of obesity, not only for the health and social care service, but for the overall economy and wider society. Belfast City Council pointed out that, “the social and economic costs of obesity are enormous and have the potential to increase significantly over the coming years."[26] The Institute of Public Health told us that, “The loss of productivity and the costs of care and treatment of obesity and related conditions have serious effects on the economy and threaten to engulf the health service. Obesity is estimated to cause 450 deaths per year, £14.2 million in lost productivity and £90 million cost to health and social care."[27]

16. The Northern Ireland Audit Office Report[28] concluded that in Northern Ireland the cost attributable to the lack of physical activity includes over 2,100 deaths each year but it found that no robust estimate of the overall health care costs of treating diabetes was available from the Department. Sustrans reminded us that the Department’s Investing for Heath Strategy back in 2002 had estimated that obesity caused over 450 deaths per annum; equivalent to over 4,000 expected years of life lost; 260,000 working days lost each year; and the approximate cost to the economy of £500 million.[29] The British Medical Association suggested that, “tackling obesity could save the health service in Northern Ireland £8.4 million, reduce sickness absence by 170,000 days and add an extra ten years of life onto an individual’s life span."[30]

17. There were also warnings that things could get worse. Professor McCartan, Sport NI, said that, “One of our concerns is that, if we do not act quickly, the problem will simply get bigger. That is why we are saying that Government must act now. The longer we delay, the more it will cost in future and the bigger the problem will be when we finally decide to act."[31]

Measuring Obesity (BMI)

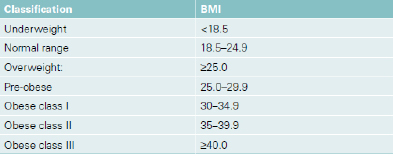

18. One of the key methods used to measure obesity prevalence around the world is Body Mass Index (BMI). BMI is a simple index of weight-for-height and is recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the most useful mechanism in providing a population-level measurement of overweight and obesity. Adults with a BMI of 25-30 are classified as being overweight and those with a BMI of 30 or more are classified as obese. However, it is also recognised that there are certain limitations associated with BMI while recent research has advocated the measurement of waist circumference as being more closely associated with mortality and morbidity than BMI.[32]

19. The Obesity Management Association, for example, argued that, “BMI as a benchmark is outdated and restrictive – it does not allow all health factors to be taken into account."[33] Dr Ryan said, “I accept that the BMI is an imperfect measure. I have been waiting for 20 years for the perfect measure. The difficulty is that meanwhile, patients are dying. We cannot wait for the perfect measure".[34]

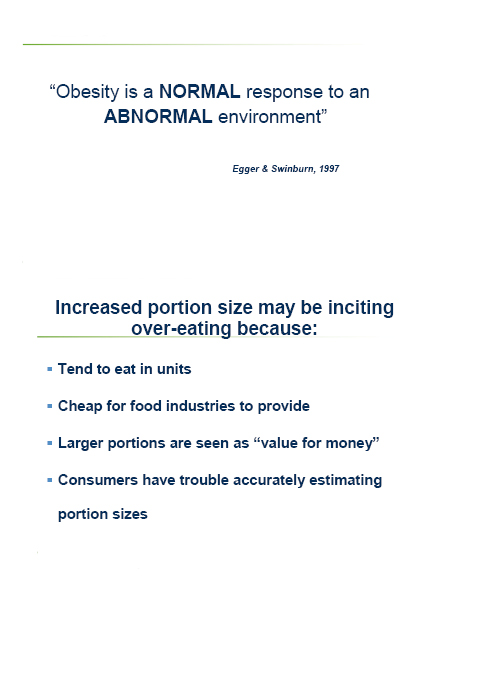

Causes of Obesity

20. Historically, obesity had been thought of as a simple matter of an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure or, in other words, an imbalance between the amount we eat and the level of physical activity we undertake. However, many of the submissions to the Inquiry were keen to point out that the cause of obesity is often a complex mix of genetic, physiological, behavioural and environmental factors. Although the specific causes of obesity at an individual level are varied it is accepted that, “at the heart of obesity lies a homeostatic biological system that struggles to maintain energy balance to keep the body at a constant weight. This system is not well-adapted to a fast-changing world, where the pace of technological progress has outstripped human evolution."[35]

21. The South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust suggested that, “obesity should be understood in a wider context than simply a lifestyle choice concerning nutrition or physical activity. Obesity is often combined with issues of mental health, self esteem, isolation, family support and emotional wellbeing."[36] Ballymena Borough Council argued that, “One school of thought would suggest that obesity is due entirely to personal lifestyle and diet choices. Another however is that people today generally do not have less willpower nor do they eat more than previous generations and that it is important to look beyond the obvious and to accept that society has radically altered over the last 5 decades, with major changes in work patterns, transport, food production and sales. It is thought that these changes have exposed a common underlying biological tendency to both put on weight and retain it.[37]

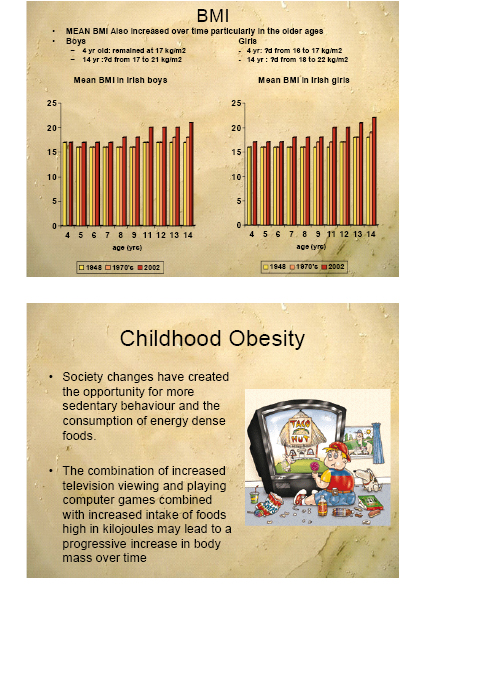

22. Action Cancer pointed out that, “it is important to remember that nobody chooses to be overweight. People choose certain behaviours that have poor health consequences."[38] Conservation Volunteers argued that, “It is recognised that the fundamental causes of obesity are lack of physical exercise and poor diet. A number of other factors are also being taken into consideration, such as increased consumption of high calorie energy dense foods, increased levels of TV watching, use of games consoles, advertising and promotion of unbalanced diet, availability of convenience food, cost of healthy food options, inadequate cooking skills, and transport and planning decisions."[39] It is also clear that there are definitive links between poverty, poor diet and obesity – see paragraphs 163 et seq.

23. It is also accepted that the pattern of growth during early life is one determinant of the future risk of obesity. “A baby’s growth rate in the womb and beyond is in part determined by parental factors, especially with regard to the mother’s diet and what and how she feeds her baby".[40] The period soon after birth is believed to be a time of ‘metabolic plasticity’ and while there is less evidence of a link between actual birth weight and obesity, it is weight gain in early life that appears to be the critical issue. Breast-fed babies show slower growth rates than formula-fed babies and this may contribute to the reduced risk of obesity later in life. It appears that low birth weight babies may be susceptible to a catch-up rapid weight gain while other babies may experience this as a direct result of their diet.[41]

24. Research published recently also suggested that there is a strong link in obesity between mothers and daughters and fathers and sons, but not across the gender divide. The study concluded that, “Childhood obesity today seems to be largely confined to those whose same-sex parents are obese, and the link does not seem to be genetic. Parental obesity, like smoking, might be targeted in the interests of the child."[42]

25. Dr Jane Wilde, Institute of Public Health in Ireland, summed it up saying, “At the heart of the problem is the imbalance between what we take in and what we put out — in other words, the energy we expend. All the studies that have examined the issue from a scientific angle say that the problem will not simply be solved by individuals … we really must take a wider view and see the problem in a social, environmental and economic context."[43] The recognition that obesity is a complex issue therefore means that it requires, as the Public Health Alliance pointed out, “integrated cross-cutting solutions and involve much more than interventions and services aimed at addressing lifestyle and behaviours".[44]

Trends

A Major Global Public Health Problem

26. In recent decades, there has been a significant rise in levels of overweight and obesity in many countries around the world. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), excess body weight poses one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century.’[45] According to the WHO’s latest projections, globally, in 2005 there were approximately 1.6 billion adults (15 years and over) overweight and at least 400 million obese. Twenty million children under the age of 5 years were overweight globally in 2005. Furthermore, the WHO projected that by 2015, there will be approximately 2.3 billion overweight adults and more than 700 million will be obese.[46] In Europe alone, it is projected that the rapidly increasing prevalence of obesity will include 150 million adults and 15 million children by 2010.[47]

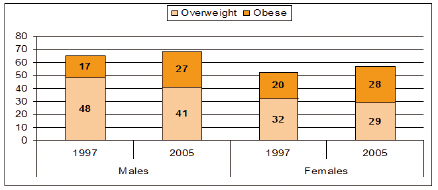

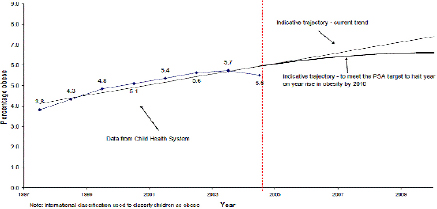

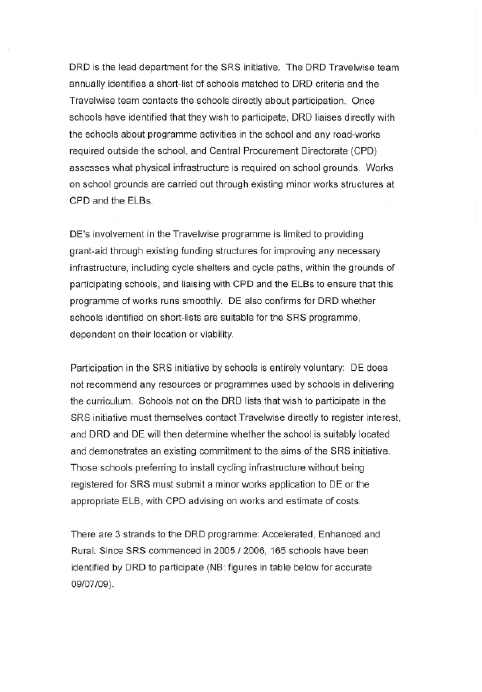

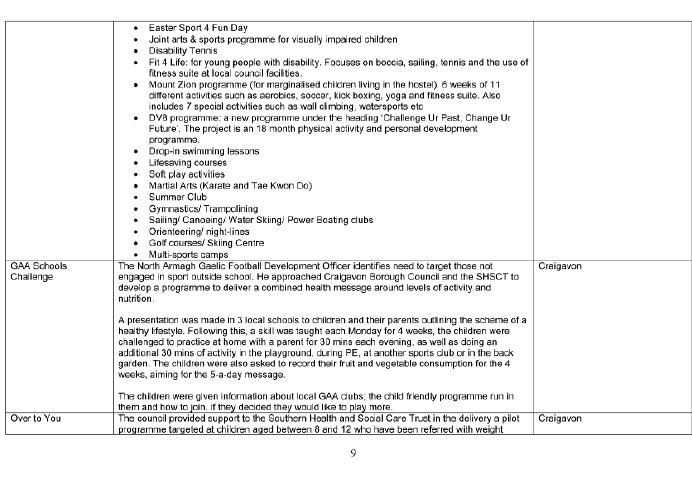

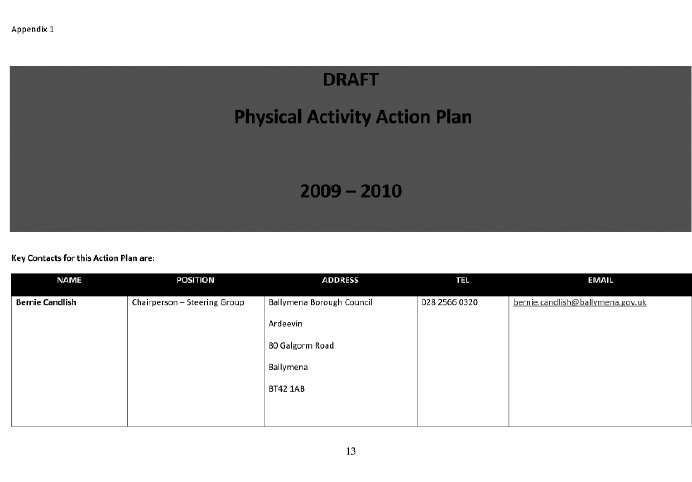

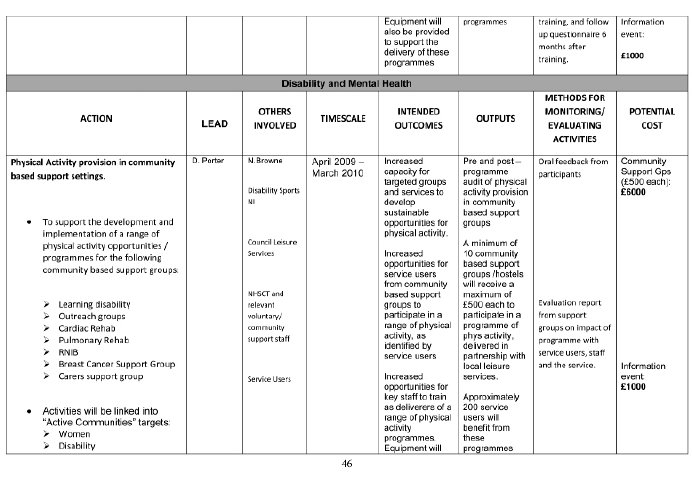

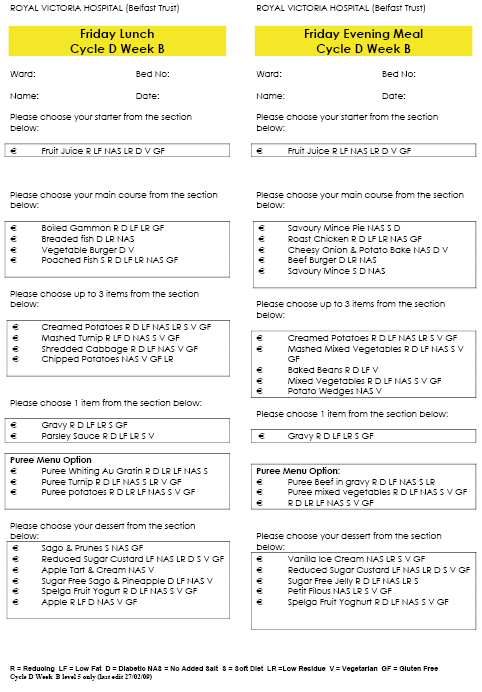

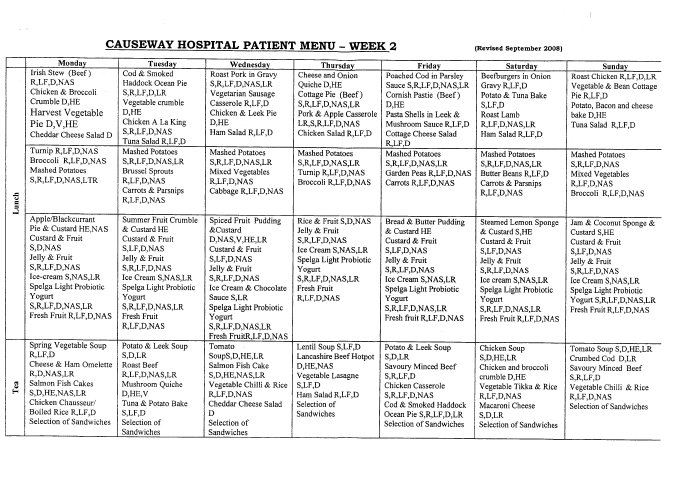

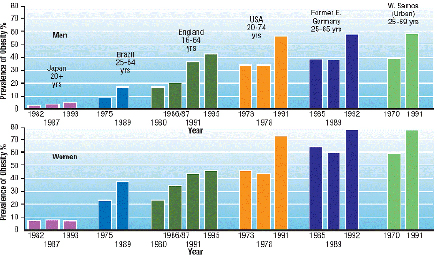

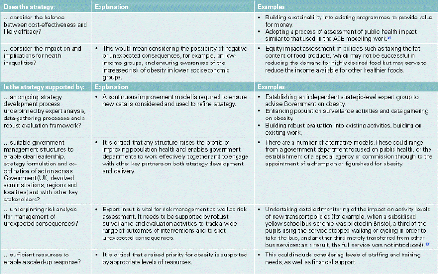

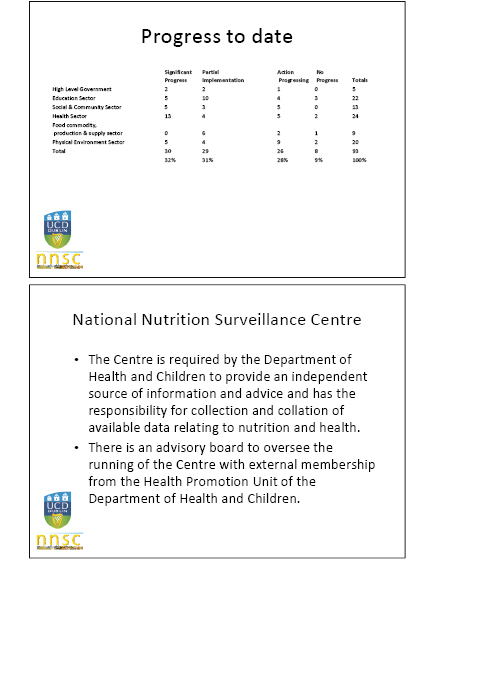

Figure 1: Percentage of the adult population assessed as obese in a selection of countries from around the world (Obese defined as BMI = 30kg/m2)[48][49]

27. A substantial body of research and empirical evidence in recent years highlights the continuing rise in overweight and obesity within both industrialized and developing/low income countries around the world. In a number of the major developed countries including the UK and the USA, the rates of obesity have doubled in the last 25 years. An OECD report published in 2009 analyzing past and projected future trends in a number of selected member countries concluded that prevalence rates of obesity and pre-obesity have been continuing to increase relentlessly in recent decades and will continue to do so in the decade ahead. The report states that, “projected trends in adult overweight and obesity (15-74 years) over the next 10 years…predict a progressive stabilization or slight shrinkage of pre-obesity rates in many countries with a continued rise in obesity rates."[50] This statement correlates with the percentage of obese adults within many of the industrialized countries around the world, including within the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland as illustrated in Figure 1. While specific figures for Northern Ireland are not included in Figure 1, levels of overweight and obesity continue to rise with around a quarter of the adult population in Northern Ireland classified as obese (see below). This follows a similar trend in other parts of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

Obesity Prevalence in UK and ROI

28. Overweight and obesity prevalence rates among children and adults throughout the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland have continued to rise in recent decades to the extent that the scale of the problem is increasingly recognized as having become an ‘epidemic’. Available data for the four jurisdictions of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland show significant prevalence rates for obesity and overweight. According to the Foresight report[51], in 2003/2004, the mean body mass index (BMI) of men and women in the UK general population was 27kg/m2, which is outside the healthy range of between 18.5-25 kg/m2. Significantly, the Foresight report warned that if trends in overweight and obesity continue to rise, there is a real prospect that by 2050, ‘Britain could be a mainly obese society’. According to the report, the rates of obesity are estimated to rise by 2035, to 47% of men and 36% of women in the UK. The headline figure that emerged from the report is that by 2050, 60% of men and 50% of women in the UK could be obese.[52]

29. Meanwhile, in the Republic of Ireland, the 2007 Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition in Ireland (SLAN) reported that 39 per cent of the adult population were overweight and 25 per cent were obese. Following a similar trend in the UK, overweight and obesity levels in the Republic of Ireland have continued to rise or remained the same over the period of the previous two surveys in 1998 and 2002. Obesity levels based on self-reported data have increased over the period of the three surveys, from 11% in 1998 to 15% in 2002 and levelled off at 14% in 2007. Overweight levels have increased between 1998 (31%) and 2002 (33%) and increased again in 2007 (36%).[53] While these figures do not include measured BMI of individuals and are reliant on self-reported data through completion of questionnaires, the data indicates there has been a significant rise in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Republic of Ireland in the last decade.

Obesity Prevalence in Northern Ireland

30. Like other parts of the United Kingdom, levels of overweight and obesity have risen significantly throughout the population of Northern Ireland in recent years. On 13 November 2008 at the opening of the All-Island Conference on Obesity (‘Obesity: weighing up the evidence’), Health Minister, Michael McGimpsey, acknowledged that “There is no doubt that the obesity time bomb in Northern Ireland is ticking louder than ever. Our level of obesity, especially amongst our children is incredibly worrying."[54]

31. At the same conference, Dr Brian Gaffney, chief executive of the former Health Promotion Agency, citing figures from Northern Ireland’s 2002 public health strategy Investing for Health stated that an estimated 450 deaths a year are attributable to obesity and that obesity costs the local economy approximately £500 million per year. Investing for Health predicted that if the upward trend in the rising obesity levels continued ‘by 2010, 23% of women and 22% of men will be obese’. The extent and seriousness of the obesity problem in Northern Ireland is reflected in the fact that figures predicted in Investing for Health were already surpassed by the figures to emerge from the 2005/06 Health and Social Well-Being Survey. According to the survey, 25% of men and 23% of women in Northern Ireland were identified as having a BMI of 30 or over and therefore classified as obese.

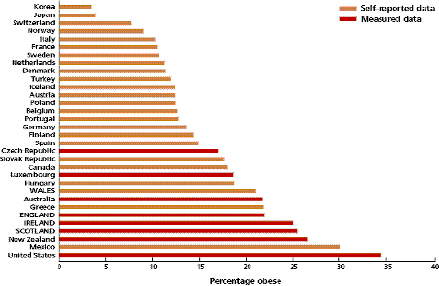

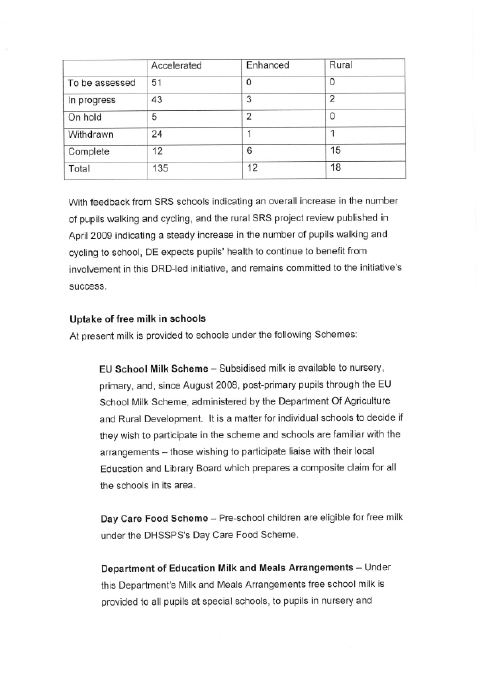

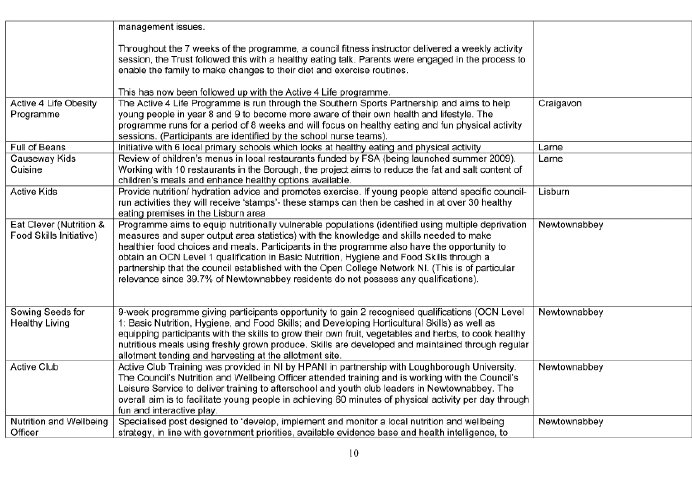

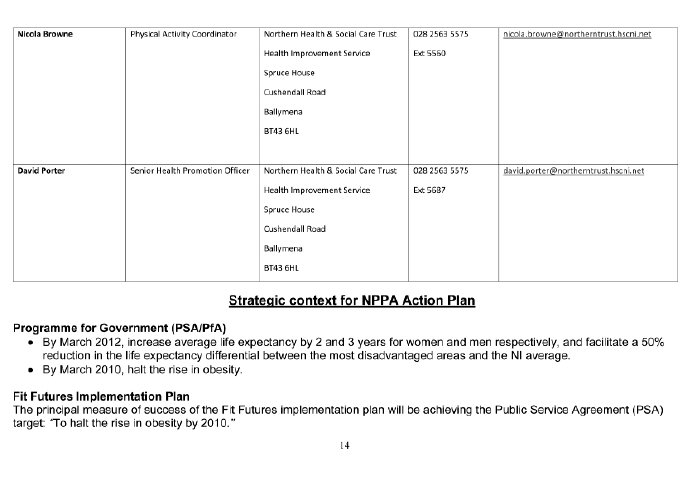

Table 1: Proportion of Adults in each Health and Social Services Board areas who were overweight or obese by gender (2005-2006)[55]

| Overweight | Obese | |||||

| HSSB | All | Male | Female | All | Male | Female |

| Eastern | 32% | 36% | 29% | 21% | 21% | 21% |

| Northern | 37% | 38% | 35% | 26% | 27% | 24% |

| Southern | 35% | 41% | 29% | 28% | 27% | 28% |

| Western | 36% | 44% | 28% | 23% | 26% | 21% |

| NI | 35% | 39% | 30% | 24% | 25% | 23% |

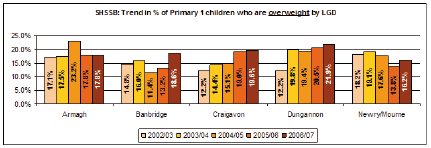

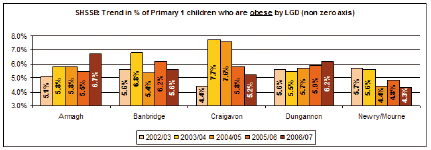

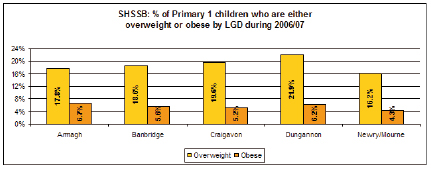

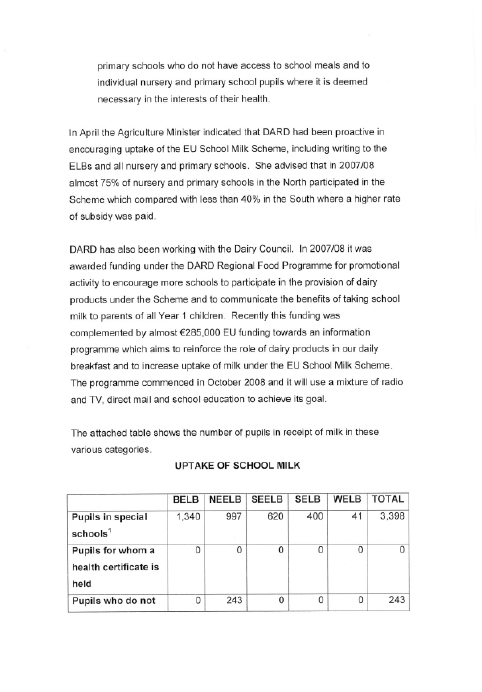

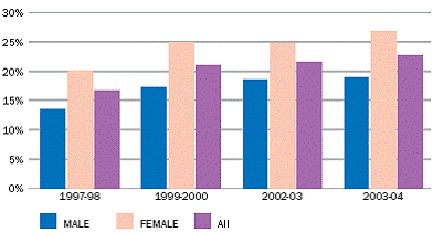

32. According to the Child Health System (managed by the former four Health and Social Services Boards) in 2003-04, one in four girls and one in five boys in Northern Ireland were found to be overweight or obese in Primary One. The percentage of children classified as obese in Primary One has increased year on year since 1997. More recent data from DHSSPS shows that the level of obesity in Primary One has declined slightly since 2003-04 from 5.7% of the age group to 5.1%. Moreover, the Young Hearts study of 12 to 15 year olds living in Northern Ireland reported that levels of overweight and obesity increased in the decade 1990-2000.[56]

33. In September 2007, the DHSSPS provided additional funding across the former four Health and Social Services Board areas to collect and record BMI measurements of all Year 8 and Year 9 pupils. In their submission to the Inquiry, the Southern Health and Social Services Board noted that, ‘To date, 89% of Year 8 pupils [have had] their weight recorded and this indicates that 11% of children weighed fell into the obese category and 1% in the underweight category’.[57]

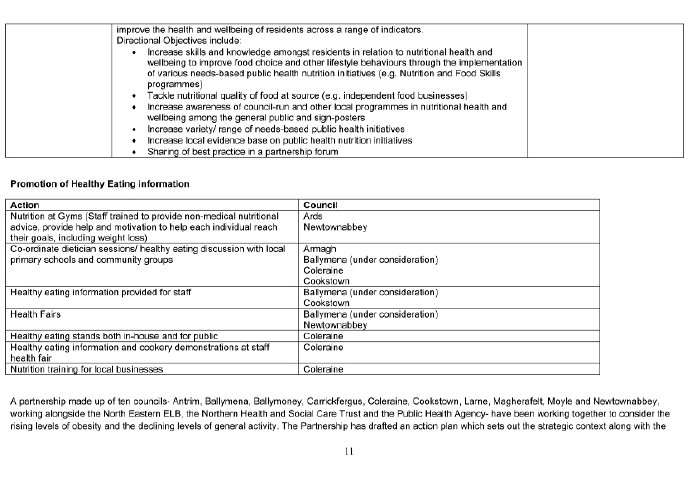

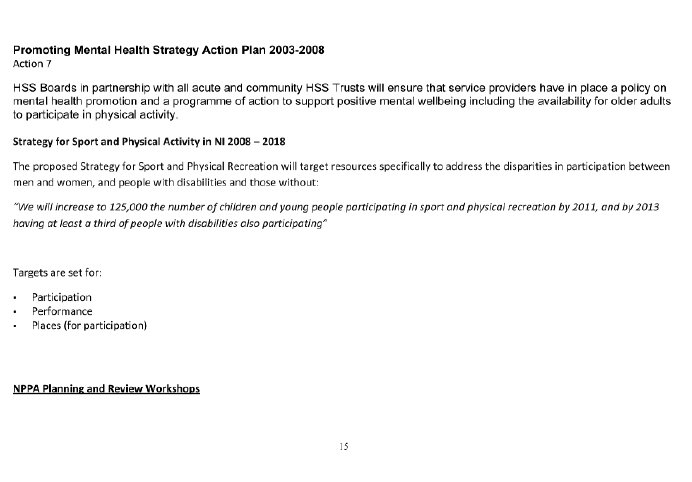

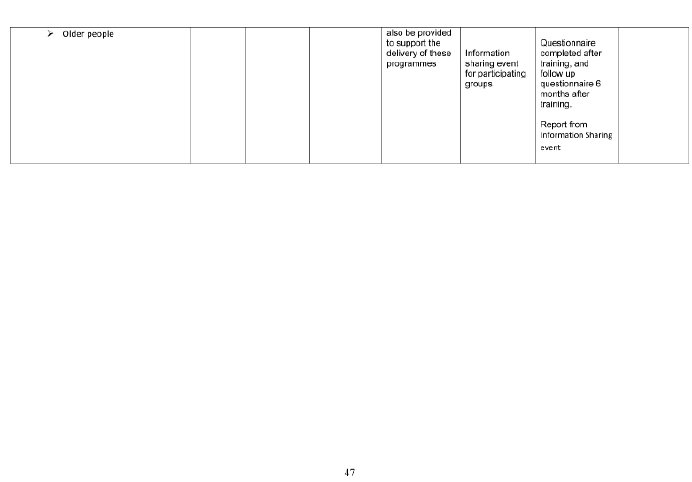

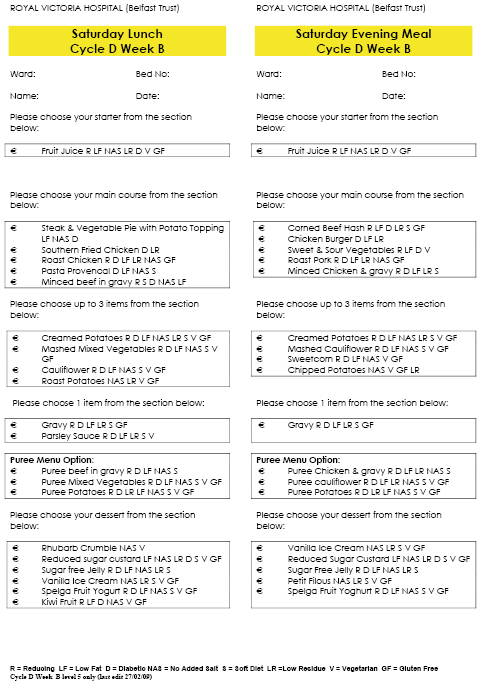

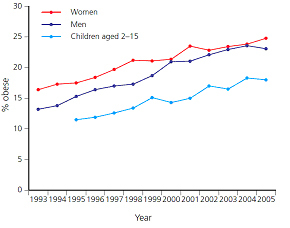

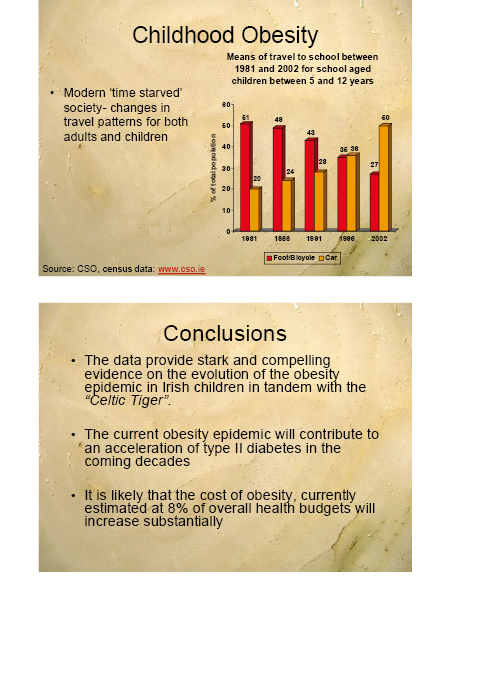

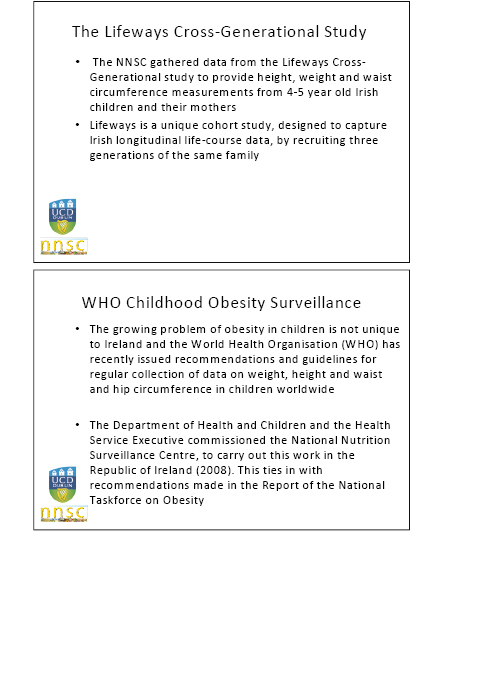

Figure 2: Obesity prevalence trends in Northern Ireland from 1997/98 to 2004/05 for P1 pupils, with possible trajectories for 2005/06 to 2010/11[58]

34. In her review of the comparative analysis of anti-obesity policies in operation throughout the devolved regions, Musingarimi[59] highlights a number of points which currently undermine the comparative analysis of the prevalence rates across the UK. Firstly, she points to the fact that in the UK data on health (including overweight and obesity) are collected separately in the devolved regions and currently there is no single UK-level obesity surveillance survey undertaken. Musingarimi argues that the employment of different methods of data collection within the UK undermines the quality of data available ‘which inhibits any truly reliable comparison of obesity prevalence rates in the four countries’. For example, data for measuring levels of obesity and overweight in England and Scotland is collected using actual measurements of height and weight, whereas in Wales and Northern Ireland less reliable self-administered questionnaires are used. Secondly, Musingarimi concludes that there are ‘critical issues’ particularly in Wales and Northern Ireland relating to the availability of reliable and accurate data on the prevalence rates of obesity

Current Approach

35. The Department in its written submission explained the development of policy over recent years in relation to tackling obesity.[60] The Department referred to the publication of the Investing for Health Strategy in March 2002 which set out how the commitment of ‘working for a healthier people’ in the Programme for Government would be achieved.

36. The development of policy subsequently included the establishment by the Ministerial Group on Public Health of the Fit Futures Taskforce to examine options for preventing overweight and obesity in children and young people. Considerable consultation and engagement took place leading to the publication of the Fit Futures Report in 2006. Following completion of the report a Fit Futures Implementation Plan was developed and published for consultation in February 2007. However, shortly after publication of the draft Implementation Plan, which focused on children and young people, the Department altered its approach stating that it recognised the need to develop a whole population approach to tackling obesity.

37. The Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People pointed to the fact that, “to date no information is available on the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) website as to the status of the implementation plan… If these actions are fully implemented it will have a positive effect on the health and wellbeing of children, in particular the levels of child hood obesity."[61] The Department acknowledged that the Fit Futures Implementation Plan was not finalised and it sought to reassure the Committee that, “while this implementation report was not formally published by the Department, progress has been, and continues to be, made to deliver on its recommendations and actions at both the regional and local level."[62]

Targets

38. The Department pointed out that the Fit Futures Report “contained a joint target, between DHSSPS, the Department of Education (DE), and the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL), ‘to halt the rise in obesity in children by 2010’"[63]. The Committee also noted that the 2002 Investing for Health Strategy contained a target ‘to stop the increase in the levels of obesity in men and women so that by 2010 the proportion of men who are obese is less than 17%, and of women, less than 20%’.[64] This target will clearly not be achieved and it may be appropriate to question the determination to do so given that the emphasis until recently has been on efforts to reduce overweight and obesity in children. The Committee notes that a review of Investing for Health Strategy is currently underway.

Funding

39. The Department in its submission to the Inquiry stated that it had “allocated £832,000 to the implementation of Fit Futures in 08/09. In addition, a further £550,000 and £300,000 has been allocated for work around promoting physical activity and improving food and nutrition respectively." By comparison the Department noted that in Scotland an additional £40 million has been allocated over a three year period under the Comprehensive Spending Review 2007.[65]

40. The provision of specific funding to address obesity was not identified by respondents as a major issue at this juncture. The Committee recognises that, while it is clear that adequate resources to tackle the problem must be provided, it is difficult to identify the extent of existing resources devoted to the issue. The Committee noted, for example, that the Department was unable to provide the Northern Ireland Audit Office with any robust estimate of the overall health care costs of treating diabetes.[66]

Life Course Approach

41. The Department advised the Committee that as a result of the findings of the Foresight report it decided to develop a life course approach to preventing obesity. As part of this the Department established a cross-sectoral Obesity Prevention Steering Group in February 2008 “to oversee the progress against the Fit Futures recommendations, and lead the development of an overarching policy to prevent obesity across the life course". To support the work of the Obesity Prevention Steering Group four policy advisory sub-groups have been set up to deal with food and nutrition; physical activity; education, prevention and public information; and data and research.[67]

42. In its final evidence to the Committee on 18 June 2009 the Department gave further details of the plans and timescale for addressing obesity across the life course. Officials stressed that the 10-year strategic framework “will be outcome-focused and outcome-based. It will take a thematic approach to the life course." The planned timescale involves the development of the framework between October 2009 and January 2010 and, following public consultation, “we hope to launch the strategy by June 2010".[68]

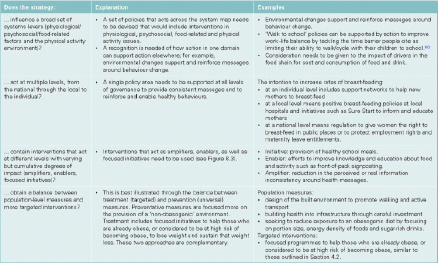

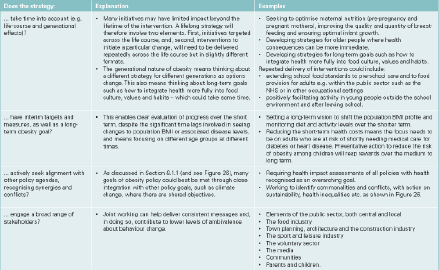

43. The proposed strategy in Northern Ireland is based on the approach adopted in the English obesity strategy Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives launched in January 2008. The English strategy, which is the only population-wide strategy being implemented in the United Kingdom currently, was developed in response to the findings of the Foresight Report.[69] The strategy in England is being taken forward by a Cross-Government Obesity Unit led jointly by the Department of Health and the Department for Children, Schools and Families and reports to a new Cabinet Committee on Health and Well-being. Clara Swinson, Deputy Director of the Cross-Government Obesity Unit in the Department of Health, told the Committee that, “in England, about 60% of adults and 30% of children are overweight or obese. The Foresight expert review, launched in 2007, said that that figure would rise if nothing was done. The experts predicted various stages up until 2050, by which time the majority of adults would be obese and only 10% would be a healthy weight... our strategy is based on the areas that are identified in the Foresight report, which looks at both individual action and the wider environment because of the obesogenic and passive-obesity issues."[70]

44. A number of respondents expressed mixed views on the Department’s current approach. Sustrans stated that, “We believe that policy in Northern Ireland is moving the right way. Fit Futures is offering a vision of joined-up policy on physical activity... However, until recently, there has been little done to actually implement Fit Futures and despite good initiatives by the Health Promotion Agency and the Physical Activity Coordinators the most recent NI Physical Activity Strategy was back in 1998-2002. It is therefore welcome and of the utmost importance, that the DHSSPS is producing an Obesity Strategy for Northern Ireland".[71]

45. However, Belfast City Council argued “that despite the increased focus afforded by government, obesity is becoming more prevalent and the current strategy and target to ‘by March 2010, halt the rise in obesity’ does not yet appear to be delivering significant outcomes."[72] Iain Foster, Diabetes UK said, “Andrew Dougal [NI Chest Heart and Stroke Association] and I sit on the Department’s obesity prevention steering group, and although it is still early days for it, neither of us is overly excited or optimistic about it making one dot of a difference to most people’s lives."[73]

46. Ballymena Borough Council expressed concern that “there appears to be no cohesive strategy available at present for guidance for those with an interest in this issue… This strategy [Fit Futures] remains in draft format although many of the key priorities contained within it are being addressed by various organisations through their own agendas ... This lack of strategic direction has led to a very ‘piecemeal’ approach to the issue of obesity".[74] Banbridge District Council called for a Northern Ireland strategy to tackle adult obesity to be “drafted and implemented as soon as possible."[75]

47. Pauline Mulholland, British Dietetic Association, expressed concern that allied health professionals are not directly involved in the obesity prevention steering group arguing that they have an important role to play on the group. She also pointed out that, “the British Dietetic Association was not invited to sit on the food and nutrition subgroup, even though such matters are our core business" but she acknowledged that this has been rectified and there is now a dietician on the subgroup.[76]

48. In developing its strategy the Department of Health in England has as its ambition “to be the first major nation to reverse the rising tide of obesity and overweight in the population by ensuring that everybody is able to maintain a healthy weight".[77] DHSSPS has also adopted an optimistic approach telling the Committee that, “there are opportunities for Northern Ireland to take a leading role in this worldwide problem by developing and implementing a cross-cutting, comprehensive, long-term strategy that brings together multiple stakeholders. The Department through its development of an Obesity Prevention Strategic Framework is determined to take on this challenge."[78]

49. Obesity is the most serious and most challenging public health issue that we face at this time and it is also one of the most complex. There is therefore an urgent need to develop and implement a comprehensive and robust strategy to address the issue.

50. We share the deep concern of those who expressed regret that the Fit Futures Implementation Plan has not been formally signed off and implemented. The failure to do so has, we believe, created uncertainty and a potential hiatus until a full strategy is in place.

51. We welcome and support the plans by the Department to develop a life course strategy however we fully recognise that tackling obesity effectively is not solely a matter for the health service. We note that the Fit Futures Report contained a joint target with the Departments of Education and Culture, Arts and Leisure. We strongly recommend that the new life course strategy be developed jointly in partnership with other departments, particularly the Department of Education, as has happened in England.[79][100]

66. Dr Wilde, Institute of Public Health in Ireland, took a similar view saying “there are hundreds of small interventions in schools, communities, workplaces, and so forth. That must be set in a regional strategy so that there is some coherence between what happens across Northern Ireland and what happens locally."[101] Pauline Mulholland, British Dietetic Association, concurred saying, “The point is to combine the best examples of what has worked across the region and to roll them out in the mainstream. At the same time, we must consider what has been tried and tested and what fits with a particular local community, because all communities are different."[102]

67. The British Medical Association felt that it was a role for the Public Health Agency to “research what works and what does not work … many people have been working hard in health action zones, and so forth, in communities. … the best practices have not been spread throughout the Province."[103] The British Dietetic Association shared the view that, “the new Regional Agency for Public Health and Social Well-being provides the opportunity to evaluate such schemes across Northern Ireland and to decide which of them to commission to create the best outcomes for the public."[104]

68. This issue was also recognised by the Public Health Agency, as Dr Carolyn Harper told the Committee, “We cannot tackle obesity through single, small-scale interventions. Given the limitations of available funding, that approach has had to be taken. However, we want to take a dual approach. First, we want to draw in additional funding, and, secondly, we want to connect the existing services and programmes not only in the health and social care service but in transport and education to get the most of that resource. We want to take a fresh look at how we connect people to all available services."[105]

69. We found that there are numerous initiatives throughout Northern Ireland aimed at addressing or preventing obesity, which have been developed and implemented by a very wide range of bodies and agencies. However, lots of these initiatives have been developed in isolation and many have not been evaluated to assess their effectiveness. In addition there is no central data collection or inventory of projects and this undoubtedly leads to duplication of effort.

70. We recommend that the Department commission an urgent audit of existing obesity-related initiatives so that the need for evaluation or further research can be identified and examples of good practice can be rolled out more widely. We recommend that the Public Health Agency, perhaps in conjunction with the planned All-island Obesity Observatory, develops and maintains a central data base of projects and develops standardised evaluation tool kits.

Weight Management

71. A major element of our terms of reference is to look at the availability of weight management and other intervention services to treat people suffering from obesity related ill health. We have already seen that around 24% of the adult population are clinically obese and many of them have significant health problems directly related to their obesity. The Department stated that, “Obesity management is integral to the management of other conditions such as coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation and diabetes."[106] Dr Michael Ryan, a consultant chemical pathologist who described himself as a ‘clinician in the front line’, told us that, “90% of the patients [he sees] for diabetes; about 80% who attend cardiac clinics; 70% who attend our gastrointestinal clinics, and about 60% who attend respiratory clinics have significant co-morbidity that is linked to weight and obesity."[107] The Obesity Management Association reminded the Committee that, “Overweight people will become obese, by which time the challenge to provide effective treatment has multiplied… Early medical intervention is essential rather than a last option".[108]

72. Dr Ryan went on to say that, “the difficulty is that there is no service for those patients. A large proportion of the population needs professional help."[109] He argued passionately in written and oral evidence to the Committee that, “the lack of a comprehensive, strategically planned service for the overweight and obese adult is a major shortcoming of the current healthcare system." He suggested that, “The current ‘system’ consists of a wide range of ‘interventions’ championed by enthusiastic and well meaning individuals but the lack of overall co-ordination renders many of the programs difficult to evaluate."[110]

Primary Care

73. The Department in its submission pointed to two elements of the 2004 General Medical Services Contract that provide incentives for GP practices to help improve the quality of care provided to patients with conditions related to obesity.[111] Under the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) GPs receive additional funding based on achievement against a number of indicators. The Department advised that since April 2006 the establishment of a register of patients who have a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 or more has been included as a QOF indicator. The Department explained that the purpose of this was to encourage GPs to “provide interventions, that would, based upon the best available evidence and recommendations by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), reduce the prevalence and severity of conditions linked to obesity".[112] In addition the Department stated that it had provided an additional £800k from 2006 by way of a Directed Enhanced Service (DES) to enable GPs to develop a written protocol for patients with a BMI of 30 or more. Directed Enhanced Services are a series of more specialised services that GPs may choose to provide.

74. The Department reported that all GP practices in Northern Ireland have fully participated in these schemes. However, Abbott, a private global healthcare company, pointed out that points under the QOF scheme are only available for maintaining a register of patients with a BMI of 30 or over and not for providing advice to patients on weight management. Abbott argued that, “allocating QOF points to obesity management, as has happened with smoking cessation, would be an effective way of incentivising better weight management in primary care and improving patient outcomes".[113]

75. Dr Theo Nugent, British Medical Association NI, suggested that GPs are well placed to identify patients with weight management problems and to manage some of the associated health related illnesses but that they “are not terribly well placed to give people good advice on how to control their obesity". He explained that, “there is little problem when someone turns up with a fallout from his or her obesity, such as diabetes. There are services available to help them to deal with that. However, a colossal workload is required when an individual is referred with what the dietetic service term ‘simple obesity’… There is a limit to where we can send people before they develop problems, and it is difficult for GPs to see how they can motivate individuals or encourage self-motivation in families."[114]

76. The British Medical Association and a number of district councils referred to the Healthwise Scheme which is run by councils in conjunction with HSC Trusts and allows participating GPs, nutritionists, physiotherapists and specialist nurses to prescribe exercise to patients they think will benefit from supervised physical activity. However, it is not available in all areas. Katrina Morgan, NILGA, explained that Healthwise, which runs in a number of council areas, “is funded by the Eastern Health and Social Services Board and offers a free 12-week programme. Patients are referred to a leisure centre to participate in the programme, and that referral can be based on anything from weight or obesity problems to general health problems. The participants are evaluated at the end of the 12-week programme."[115] Teresa Ross, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, gave further details saying, “the fitness instructor and the physiotherapist in a leisure centre work in partnership to assess the patient and set up an individual programme for them. The fitness instructor then takes control of the exercise programme."

77. Ms Ross suggested that this was “a positive way to progress and would allow the health system to target people who are at risk of ill health, as opposed to those who are actually ill. Therefore, it is important to develop the idea of prescribing exercise, and it should be rolled out."[116] Gerry Bleakney, Public Health Agency, confirmed that, “there is a scheme in the eastern area and part-schemes in the southern and northern areas." However, she suggested that “the evidence base to support it is questionable ... Clients from general practice, primary care and secondary care give good reports about the scheme in the east, and we think that it is working. We will continue to assess the scheme because it is an expensive intervention. It is also a potentially very cost-effective intervention given the health outcomes that it creates."[117] The Western Health and Social Care Trust advised that there are three successful GP exercise referral schemes running in the western area.[118]

78. Professor Eamonn McCartan, Sport NI, argued strongly that, “GP referrals can address some of the barriers that prevent people who are not particularly active, who are overweight and who have an issue with their body image from exercising… People need a pathway, encouragement, direction and mentoring. That can be done, particularly for those social groups that cannot see the benefits of physical activity and exercise."[119]

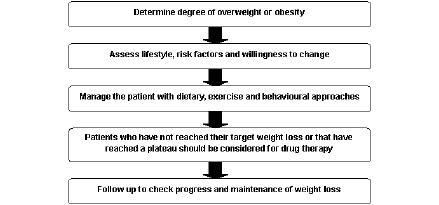

79. The Committee noted that an evidence-based Care Pathway for the management of overweight and obesity in primary care was published by the NHS in England in 2006. For adults, the priority of intervention in primary care is reducing risk factors for the patient “rather than to return them to an ‘ideal’ or healthy weight range".[120] This acknowledges the fact that small weight losses do produce health benefits, while more significant changes result after a loss of 5-10 per cent of body weight. The aim is also to prevent further weight gain in patients with lower degrees of overweight.

80. A good practice example of a Primary Care Specialist Obesity Service, established to treat people with morbid obesity within a primary care setting, is that established by Birmingham East and North PCT. The aim of the service is to provide more intensive specialist support, than would generally be possible in a primary care setting, from a multi-professional team.[121]

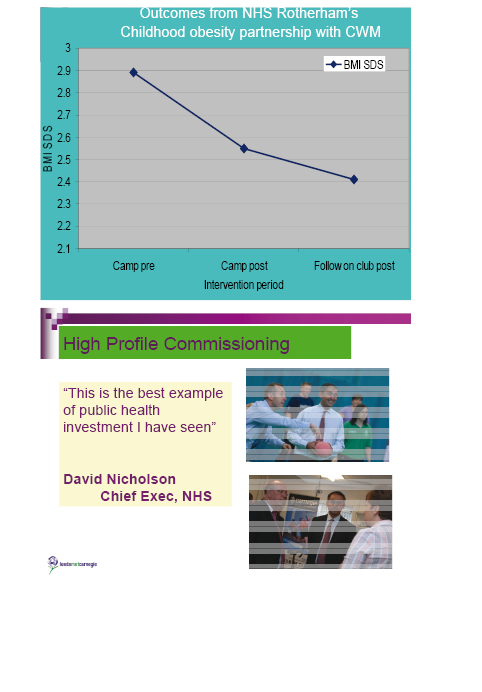

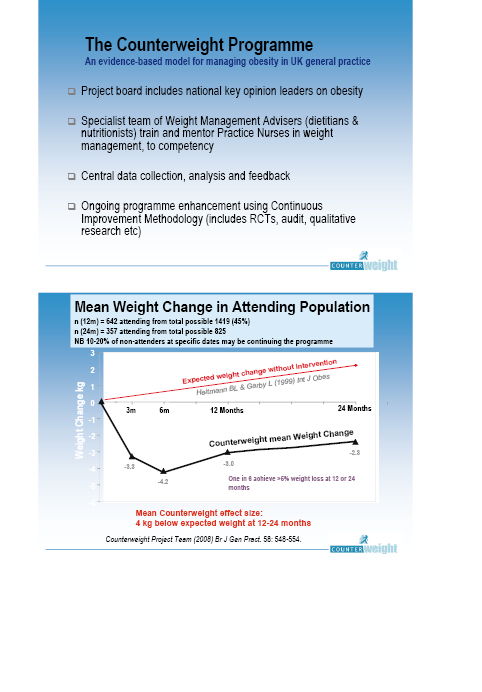

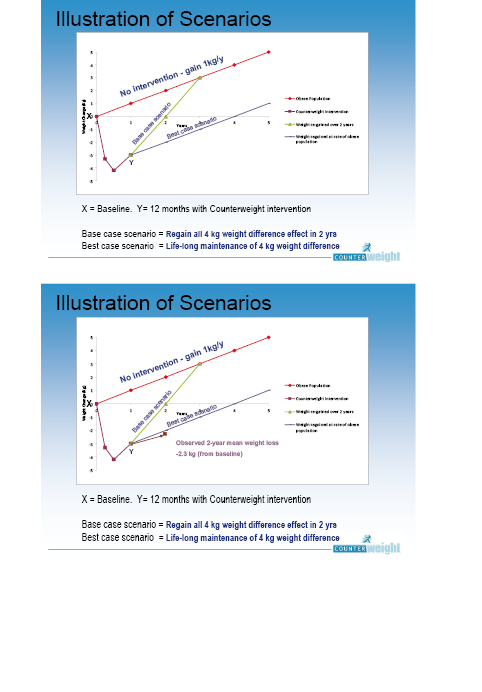

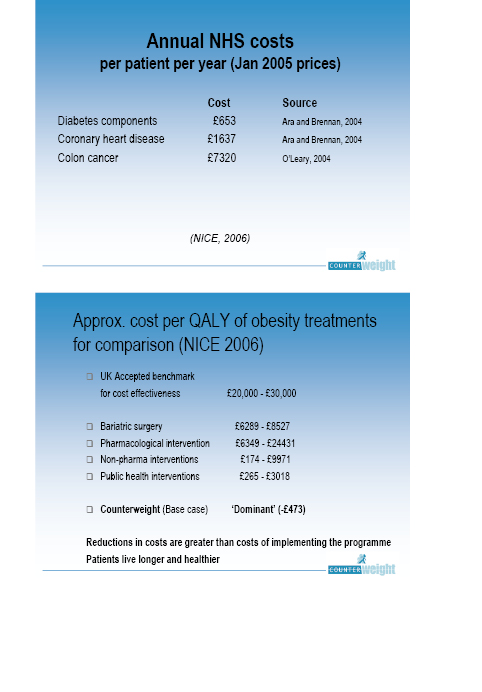

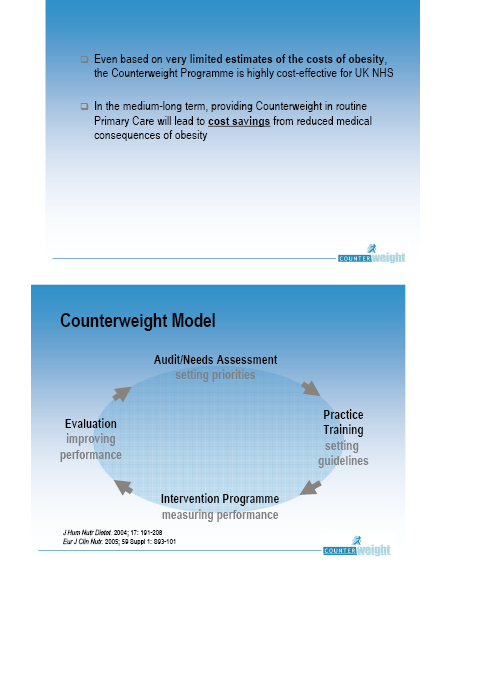

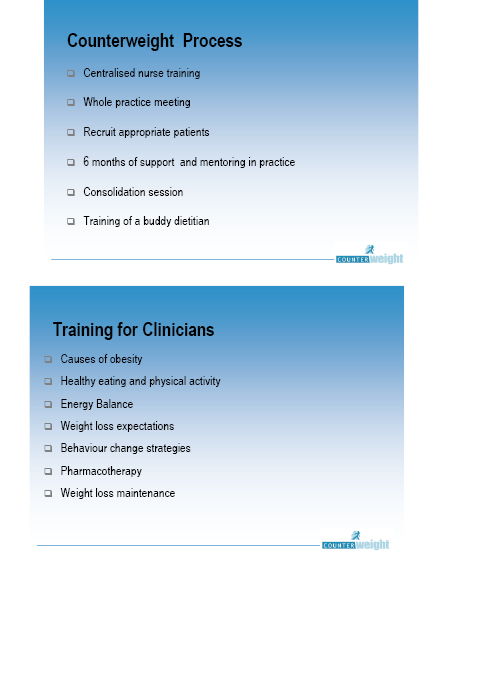

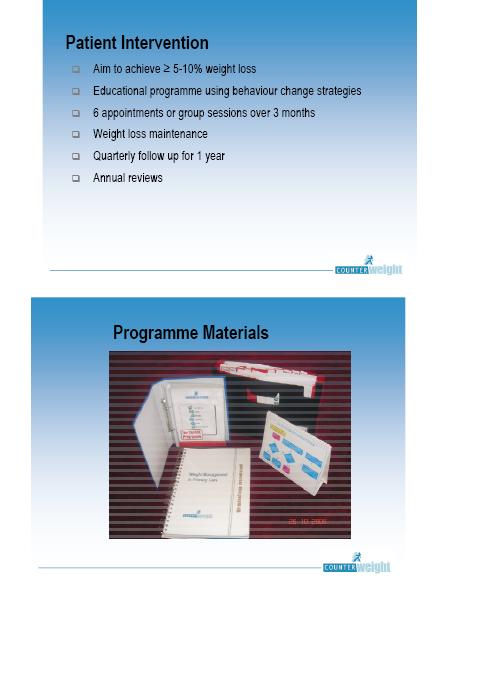

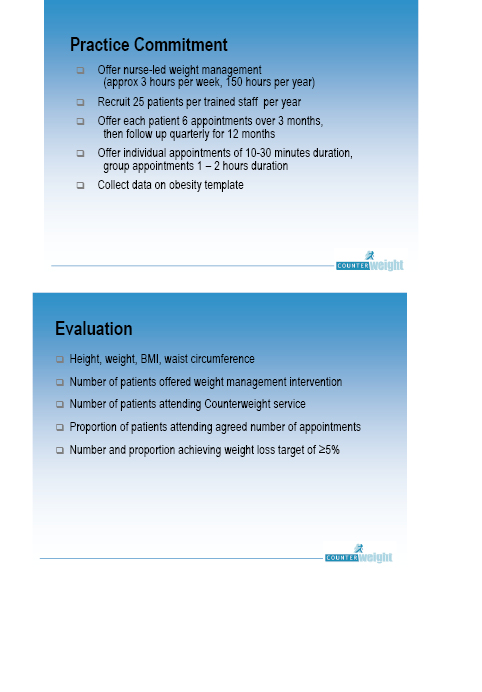

81. Dr Ryan suggested that we adopt the approach of the Counterweight programme used in Scotland. He explained that it “is primary-care based and provides specifically trained staff to deal with obesity. It is rigorously evaluated by the University of York and the University of Aberdeen. Counterweight has produced credible evidence of the cost-effectiveness of that type of programme."[122] Professor Iain Broom, Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen and Chairman of Counterweight, and a colleague Hazel Ross, took part in the Committee Research Event and elaborated on the Counterweight programme and confirmed that it “is the first large scale primary care weight management programme in the UK to show clinically effective weight reduction using a structured approach to care".[123]

82. We are concerned about the lack of clear direction for dealing with obesity in primary care settings in Northern Ireland. We are also concerned that initiatives such as the Healthwise Scheme, whereby supervised physical activity can be prescribed, are not available in all areas. We recommend that the Department, in conjunction with the Health and Social Care Board, develops a range of evidence-based referral options for use by primary care practitioners.

83. We urge the Minister to exert influence at a national level to introduce the allocation of Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) points for positive obesity management rather than simply for maintaining a register of obese patients.

Secondary Care

84. The Department told us that, “Patients with significant weight management/obesity issues which may be directly or indirectly linked to their condition are seen and treated in almost every service within secondary care… Historically it has been the presenting condition that is treated and managed, although obesity issues may be one of a number of contributing factors in the development of the disease/condition."[124]

85. Dr Ryan argued that this was still the case saying that, “Current clinical services, designed to address specific clinical conditions, such as diabetes, cannot adequately address the special needs of the obese patient. Clinical services are becoming effectively ‘silted up’ with patients whose primary cause for attendance is ‘overshadowed’ by the co-morbidity of excess weight. Addressing the obesity can be more beneficial, in terms of health gain for the patient, than dealing with the ‘primary’ cause of attendance."[125] The Department did acknowledge that, “specialist supporting dietetic services need to be further developed to meet current and anticipated future demands. There will need to be additional staff, primarily dieticians and nurses, and training/specialist knowledge enhanced in secondary care."[126]

86. Pauline Mulholland, British Dietetic Association, stressed the key role undertaken by dieticians in the management of clinical obesity and said that, “People aspire to lose a significant amount of weight over a short period, and sometimes that puts them off accessing our services. We need to manage such expectations and promote the message that if individuals can be encouraged to lose 10% of their weight and to maintain that weight loss, they can achieve significant health benefits. The evidence shows that a 10% weight loss will reduce blood pressure and cholesterol, improve the control of blood sugar for people with diabetes, and reduce the death rates for a number of conditions."[127]

87. Dr Ryan argued for the use of a managed clinical network model of services delivery saying that, “it is now well established and has been shown to be an effective means of delivering targeted services for specific reasons. The approach to weight management at all levels of intervention should be supported by the managed clinical network. Much of the cost of such a programme is already embedded in the system".[128]

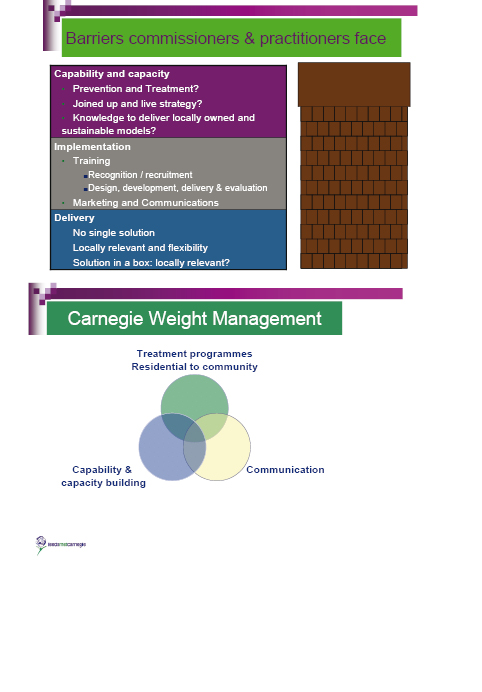

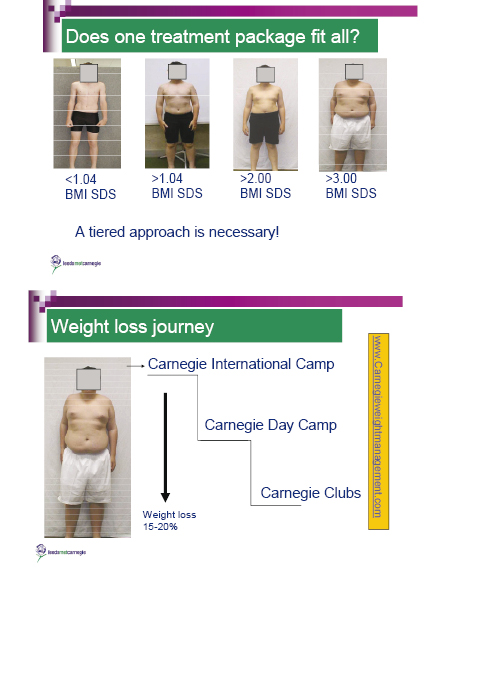

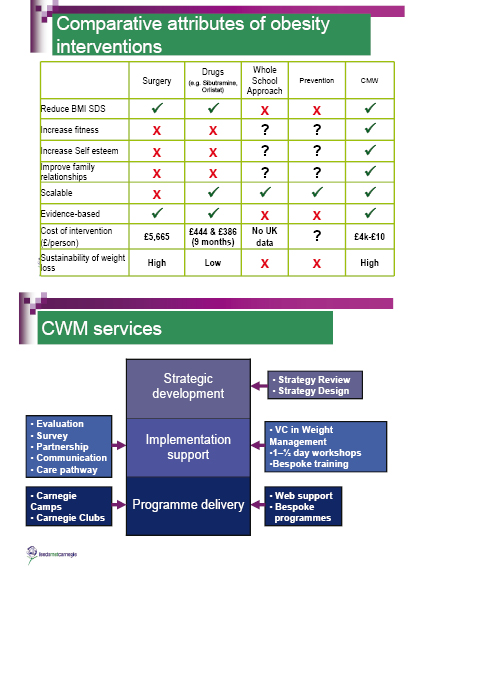

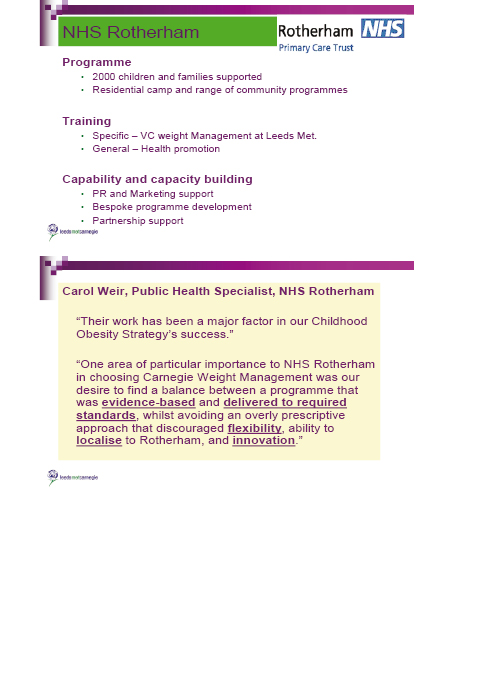

88. The need for effective interventions for children was also highlighted to the Committee. Currently one in four children in Northern Ireland is either overweight or obese and Dr Wilde, Institute of Public Health in Ireland, pointed out that, “The evidence shows that most children who are overweight or obese carry that through the rest of their lives."[129] Dr Mark Rollins, consultant paediatrician, argued that, “there are 400,000 children in Northern Ireland, 100,000 of whom are currently overweigh and obese. Some 60% to 70% of children are going to be obese as adults. That is a fact… In Northern Ireland, we have no intervention programmes at all. We are starting from a complete base."[130]

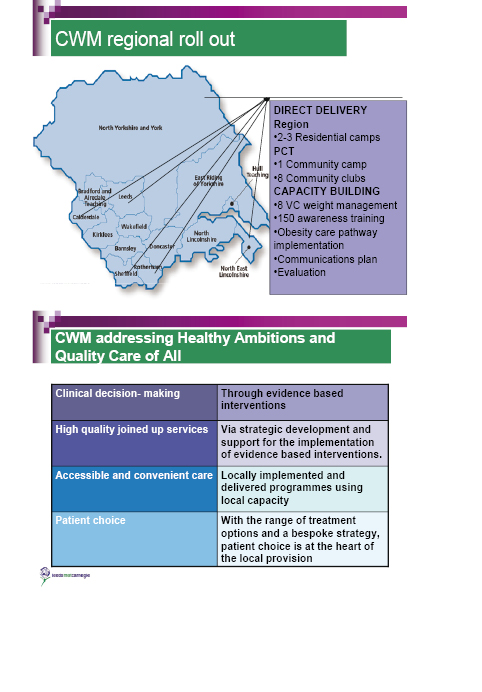

89. At the Committee Research Event Professor Paul Gately, Professor of Exercise and Obesity at Leeds Metropolitan University, spoke about an academic unit called Carnegie Weight Management that he leads. He highlighted a major concern that while “there are 4.5 million children in the UK who are overweight or obese… 70% of parents identify their overweight child as having normal weight".[131] Carnegie Weight Management provides family based multi-disciplinary intervention programmes at a range of levels from after-school activities to a residential camp for severely obese children. The Committee noted ongoing discussion between Carnegie and clinicians in the Northern Health and Social Care Trust and welcomed plans by Helping Hand Ltd to develop five pilot intervention programmes based on Carnegie for post primary children throughout Northern Ireland.[132]

90. The former Southern Health and Social Services Board stated that, “People who are obese are initially provided with advice through primary care services. They can access specialist drug treatments and dietetics advice through this route. NI has high rates of prescriptions of drug treatments for obesity. There is little evidence that attendance at specialist secondary care obesity clinics is more effective in achieving weight loss than interventions in primary care. However, such clinics may have a role in assessing patients who may be eligible for surgical intervention. As NI does not have a surgical treatment programme, there is no specialist obesity clinic in NI at present."[133]

91. The former Western Health and Social Services Board took a different approach arguing that, “while many patients can be managed in a community obesity clinic setting, there is a need for investment in specialist services in secondary care. We acknowledge that physicians in diabetes and endocrinology are appropriate specialists to manage such a service. However, they are already overwhelmed by the demand, as the diabetes epidemic has put additional pressure on the services that they are facing."[134]

Bariatric Services

92. The needs of very severely obese patients often require special services. Tracey Gibbs, College of Occupational Therapists, explained that, “On a day-to-day basis, that has major implications for transporting patients in hospital beds, the use of hoists and porters’ chairs, and for the use of seating in hospitals and in the patient’s home." However, she cautioned that “Although there is a lot of emphasis on the global epidemic of obesity, it is also important to consider the needs of the obese person. It must be ensured that they are treated with respect and dignity and that stigma and discrimination are avoided. A person who is overweight may feel socially isolated or excluded."[135]

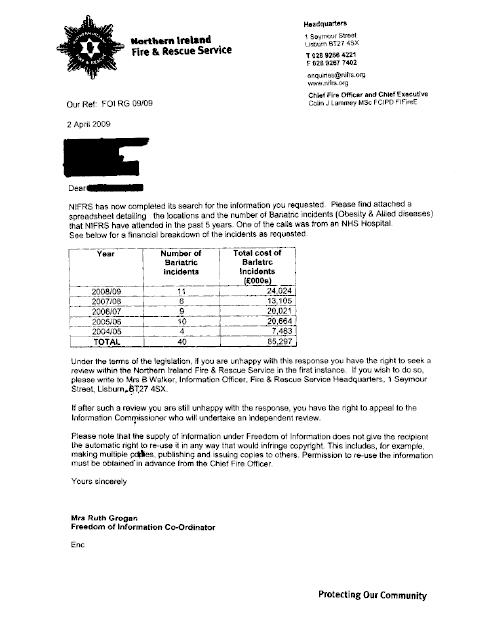

93. In the course of the Inquiry the Committee learned, for example, that the NI Fire and Rescue Service had been called out on 40 occasions over the past five years to deal with bariatric incidents at a total cost to the Fire and Rescue Service of £85,000. These were mainly calls to assist ambulance personnel or other health services staff to deal with severely obese patients.[136]

94. Bariatric surgery has increasingly been used as a method of treating severely obese patients when other approaches fail and research suggests that this type of surgery has increased “more than five-fold within 5 years in most developed countries".[137] Bariatric procedures can be divided into those that reduce food intake (gastric restrictions) and those that reduce food uptake from the digestive tract (malabsorption).

95. Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 2008 recommended that bariatric surgery to aid weight loss should be available to patients meeting certain body mass index (BMI) criteria. The former Southern Health and Social Services Board told us that, “It is estimated that there are more than 50,000 people in NI who could be eligible for bariatric surgery using NICE criteria. This number is expected to rise at a further 5% each year. Although NICE estimate that only 2-4% of these people would come forward for surgery, this is by no means certain. The cost of treating only 2% of the eligible NI population (i.e. 1,000 patients) and providing the necessary long-term follow-up could be in the order of £10 - £15 million."[138] The Board also explained that “a multidisciplinary team assessment is necessary to ensure patient suitability for surgery and the long-term lifestyle changes it requires. In addition, surgeons need to be able to offer a full range of techniques, including laparoscopic surgery, and undertake a minimum volume of procedures to achieve and maintain skills. Appropriate follow up services, including the input of dieticians and specialist physicians, need to be in place. At present not all of these skills are available within NI… In light of the potential numbers of patients in NI who would meet NICE criteria, the current funding position, and the financial consequences of providing treatment for all those who might present, it has been agreed by Boards that, within the current CSR period, bariatric surgery cannot be commissioned routinely for patients meeting the NICE-recommended BMI criteria."[139]

96. The former Western Health and Social Service Board agreed saying that, “There is a lack of funding around bariatric services for patients in Northern Ireland who have persistent obesity when lifestyle and other drugs fail. Bariatric surgery has been shown to reverse diabetes and reduce mortality and there is an issue about equity to services which are available in other parts of the UK."[140]

97. David Galloway, DHSSPS, told us that, while bariatric surgery is not currently commissioned by the health boards in Northern Ireland, “last year, £1·5 million was made available to ensure that some 120 people had access to bariatric surgery from providers in Great Britain. The boards are currently discussing how they might progress that issue in 2009-2010 to ensure that that service is provided to the people who are most likely to benefit from it."[141] The Department subsequently advised that approximately 80 patients had bariatric surgery outside Northern Ireland in 2008/09 and that “for 2009/10 the legacy Health Boards agreed to fund short term bariatric services pilot with a budget of £1.5m and a target of providing treatment in England during the year for between 100 and 150 patients. The Department has no plans at this time to provide this surgery in Northern Ireland."[142]

98. Elsewhere in this report we deal with the need for a strategic approach to the prevention of obesity. However, we are gravely concerned about the extent of existing obesity-related ill health and the distinct absence of appropriate services at all levels. We are shocked to learn of the number of severely obese patients that attend diabetic and other clinics and particularly by the realisation that more than 50,000 people in Northern Ireland may be eligible for bariatric surgery.

99. We highlight the fact that even a modest reduction in weight can have a significant impact on a patient’s health and that addressing obesity may be more beneficial than dealing with the resulting illness.

100. We call on the Minister, as a matter of urgency, to undertake a thorough review of weight management services at all levels for both adults and children. The review must address the need for dedicated obesity clinics and the critical and urgent need for a separate bariatric service for Northern Ireland, including the provision of bariatric surgery and the lifelong medical follow-up for individuals required following such surgery. The review should also consider the merits of adopting examples of good practice from elsewhere, such as the Counterweight programme in Scotland and the Carnegie Weight Management programme in England.

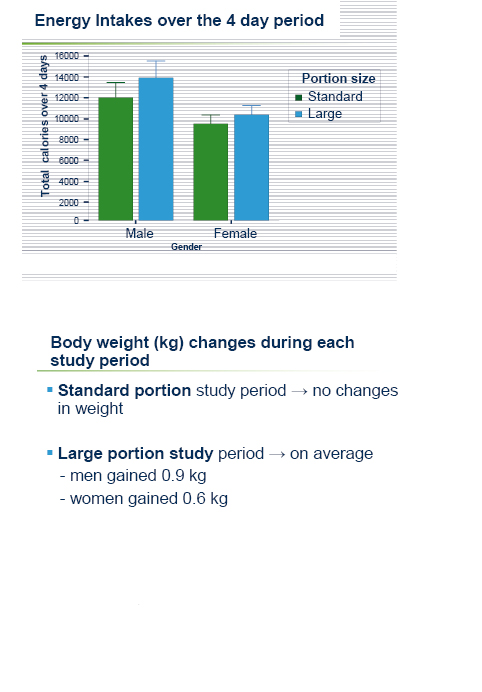

Diet And Exercise

101. While the rapid increase in obesity over recent decades has not simply been down to an imbalance between diet and exercise it is clear that these two issues need to be addressed from a range of perspectives. As Newry and Mourne District Council pointed out “poor dietary habits and decreasing physical activity have become ingrained in the population and it will take a long-term approach involving many organisations to make any substantial changes in this culture".[143] In this chapter we look at what is being done to address these issues and to encourage the adoption of healthier lifestyles.

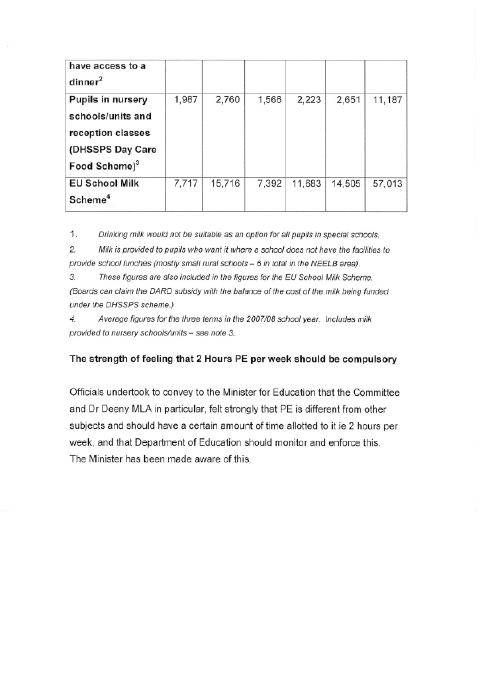

Healthy Eating