| Homepage > The Work of the Assembly > Committees > Health, Social Services and Public Safety > Reports | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Health, Social Services and Public Safety CommitteeReport on the Autism BillTogether with the Minutes of Proceedings, Minutes of Evidence and Ordered by The Health, Social Services and Public Safety Committee to be printed 10 February 2011 Session 2010/2011Third ReportMembership and PowersThe Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 48. The Committee has power to:

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5. The membership of the Committee is as follows: Mr Jim Wells (Chairperson) Mr Mickey Brady [1]With effect from 20 May 2008 Mrs Claire McGill replaced Ms Carál Ní Chuilín. With effect from 15 September 2008 Mr Sam Gardiner replaced Rev Dr Robert Coulter. With effect from 29 June 2009 Mrs Dolores Kelly replaced Mr Tommy Gallagher With effect from 4 July 2009 Mr Jim Wells replaced Mrs Iris Robinson With effect from 14 September 2009 Mrs Iris Robinson replaced Mr Thomas Buchanan With effect from 12 January 2010 Mrs Iris Robinson resigned as an MLA With effect from 15 January 2010 Mrs Carmel Hanna resigned as an MLA With effect from 26 January 2010 Mr Conall McDevitt replaced Mrs Carmel Hanna With effect from 1 February 2010 Mr Thomas Buchanan replaced Mrs Iris Robinson With effect from Monday 24 May 2010 Mr Tommy Gallagher replaced Mr Conall McDevitt With effect from Monday 24 May 2010 Mrs Mary Bradley replaced Mrs Dolores Kelly With effect from Monday 13 September 2010 Mr Mickey Brady replaced Mrs Claire McGill With effect from Monday 13 September 2010 Mr Paul Girvan replaced Mr Thomas Buchanan With effect from Monday 23 November 2010 Mr Pól Callaghan replaced Mrs Mary Bradley Table of ContentsClause by Clause consideration of the Bill Appendix 1:Appendix 2:Appendix 3:Appendix 4:Appendix 5:Appendix 6:Executive SummaryThe purpose of the Bill is to enhance the provision of services to and support for people with conditions which are on the autistic spectrum. It does so by amending the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA) so as to resolve any ambiguity as to whether the term "disability" applies to autistic spectrum disorder (ASD), and by requiring the preparation of a cross-departmental autism strategy. The evidence from the stakeholders was wide-ranging and many different views on the Bill were expressed. Some organisations welcomed the Bill in its entirety, others had concerns with particular clauses, while some groups opposed the Bill completely. The first key issue for the Committee was in relation to clause 1 of the Bill. Clause 1 seeks to amend both the definition of disability as set out in the DDA and the list of "normal day to day activities" contained in Schedule 1 of the DDA. In overall terms, some organizations supported this clause because they took the view that it would enhance the ability of those people with ASD to claim protection under the DDA. However, other groups held the opposite view and argued that any changes to the DDA could potentially exclude those same people from its protection. The Committee suggested to the Sponsor of the Bill, Mr Bradley MLA, that to amend the current definition of disability as a "physical or mental impairment" could in fact narrow the scope of people who could fall within the definition of disability. Mr Bradley accepted the Committee's view and agreed to draft an amendment to leave out clause 1 (2) of the Bill. In relation to clause 1 (3) of the Bill which seeks to expand on the list of "day to day activities" contained in the DDA, the Committee took the view that the Bill was following a similar approach to that contained in guidance currently being consulted upon for the Equality Act 2010. The Committee agreed it was content with this clause as drafted. The second key issue concerned the preparation of an autism strategy. Some stakeholders argued that legislation is required to ensure that all government departments work in a joined up manner to produce a comprehensive strategy to deal with ASD. Other organisations took the view that the current departmental strategies were working well and that a new strategy would result in more bureaucracy. The Committee came to the view that a legislative requirement for all government departments to co-operate in the production of an autism strategy was a positive step forward and would ensure input from all departments. The third key issue concerned the content of the autism strategy. Clause 3 (5) of the Bill requires autism awareness training for civil servants who deal directly with the public. Concerns were expressed by stakeholders that this would have significant cost implications. The Committee suggested that training might be better directed at frontline public sector workers in the fields of health and education rather than at civil servants. Mr Bradley accepted the Committee's view that the clause was problematic and agreed to draft an amendment to leave out clause 3 (5) of the Bill. IntroductionThe Autism Bill (NIA 2/10) was referred to the Committee in accordance with Standing Order 33 on completion of the Second Stage of the Bill on 7th December 2010. The Sponsor of the Bill, Mr Dominic Bradley MLA made the following statement under Standing Order 30: "In my view the Autism Bill would be within the legislative competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly." The stated purpose of the Bill is to enhance the provision of services to and support for people with conditions which are on the autistic spectrum. The Bill will amend the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 and require an autism strategy to be prepared. During the period covered by this report, the Committee considered the Bill and related issues at eight meetings. The relevant extracts from the Minutes of Proceedings for these meetings are included at Appendix 1. The Committee had before it the Autism Bill (NIA 2/10) and the Explanatory and Financial Memorandum that accompanied the Bill. The Committee agreed a motion to extend the Committee Stage of the Bill to 11 February 2011. The motion to extend was supported by the Assembly on 24 January 2011. On referral of the Bill the Committee wrote on 10 December 2010 to key stakeholders and inserted public notices in the Belfast Telegraph, Irish News and News Letter seeking written evidence on the Bill by 6 January 2011. A total of 33 organisations responded to the request for written evidence and copies of the submissions received by the Committee are included at Appendix 3. The Committee took oral evidence from:

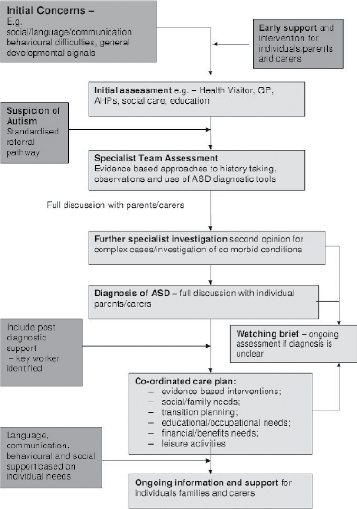

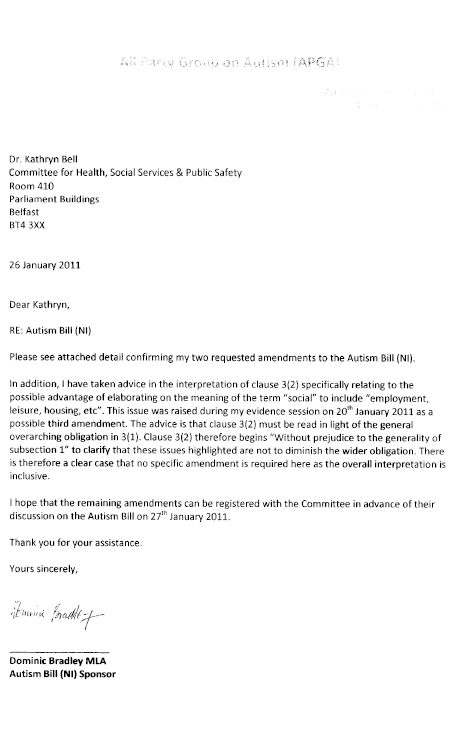

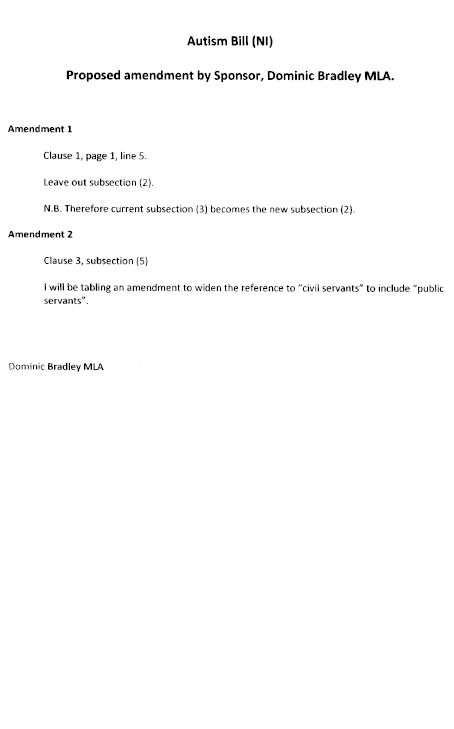

The Minutes of Evidence of these sessions are included at Appendix 2. The Committee carried out clause by clause scrutiny of the Bill on 27 January 2011. At its meeting on 10 February 2011 the Committee agreed its report on the Bill and that it should be printed. Consideration of the Bill by the CommitteeBackgroundAutism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex developmental condition that essentially affects the way a person communicates and relates to people. People with autism generally experience three main areas of difficulty, which are commonly referred to as 'the triad of impairments'.

The Autism Bill was proposed by Mr Dominic Bradley MLA, chairperson of the All-Party Assembly Group on Autism which was formed in 2008 to attempt to inform Assembly Members about autism issues. Proposals for the Bill were developed as a consequence of the work of the group and its engagement with stakeholders. The All-Party Assembly Group on Autism decided that it was important to advocate a cross-departmental regional strategy for ASD, linked to, and supported by, legislation. The Bill has 7 clauses and no schedules. Key IssuesClause 1 - Amendment to the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995The Bill's Sponsor Mr Dominic Bradley stated the aim of amending the DDA was to clarify that people with ASD fell within its scope. In his view, there is an ambiguity as to whether those people on the autistic spectrum are current covered by the DDA and this can have a detrimental effect on their ability to access services and benefits. During an oral evidence session prior to the introduction of the Bill on 14 October 2010, Mr Bradley explained the purpose of clause 1 as follows: 'To ensure that ASD is included, it amends the definition of disability in the existing Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995 by inserting: "social (including communication)". The draft Bill, therefore, provides more clarity for the Departments and public bodies that use the DDA definition of disability as guidance when making decisions, for example, on disability living allowance (Appendix 2)'. A number of organisations supported Mr Bradley's stance on the need to amend the DDA including Autism NI, the Human Rights Commission, Autism Initiatives, Action for Children and the Parent's Autism Lobby (PAL). However, other groups held the opposite view and argued against any changes to the DDA. These groups included the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), the Regional Autism Spectrum Disorder Network (RASDN), the Reference Group of RASDN, the Health and Social Care (HSC) Board, Aspergers Network, the Equality Commission, a number of the Education and Library Boards, Carers NI, the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, the Royal College of General Practitioners, and a number of the (Health and Social Care) HSC Trusts. Many of these groups were of the opinion that ASD was already covered by the DDA and that amending the DDA would not have the desired effect of increasing access to social security benefits. During oral evidence on 20 January 2011 the DHSSPS stated: 'The Department believes that autism is covered by the current DDA, which is evidenced by case law, and I am happy to talk about case law if you want me to. The Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister guidance on the existing DDA clearly states that autism is covered (Appendix 2)'. Similarly, oral evidence from the Regional Autism Spectrum Disorder Network on 16 December 2010 supported this view: 'Our perception is that the Children Order and the DDA are all-encompassing. It is of concern to us that the focus would be on specific conditions rather than on the broad spectrum of people with a disability. We should look across our services — universal services as well as specialist services — to support people with disabilities who live in our communities. We contest the notion that not including autism in the DDA creates inequalities (Appendix 2)'. At its meeting on 20 January 2011 the Committee considered a research paper (Appendix 4) which indicated that the term 'physical or mental impairment' had intended to be all encompassing when the DDA was originally introduced. The paper also noted that a view had been put forward in other jurisdictions that to amend the term "physical or mental impairment" could in fact narrow the scope of people who could fall within the definition of disability. When the Committee took evidence from Mr Bradley on the Bill, it raised the issues of concern relating to clause 1. Mr Bradley advised the Committee that he had further considered the issue of amending the definition of disability and had come to the decision leave out clause 1 (2) from the Bill. The Committee welcomed Mr Bradley's amendment to the Bill. The need to legislate for an Autism StrategyMr Bradley stated that there is a lack of co-ordination currently between the Department of Education and Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety in terms of delivering strategies to address the needs of people with ASD. In his view legislation is required to ensure that all government departments work in a joined up manner to produce a comprehensive strategy to deal with ASD. This position was supported by Autism NI, the College of Occupational Therapists, Autism Initiatives, Action for Children, Carers NI and the Parent's Autism Lobby. For example Autism NI stated during oral evidence on 16 December 2010: 'We believe that the legislation can only strengthen and empower that which is already happening. At the moment, there is limited buy-in from other Departments. The DHSSPS ASD strategy relies on a medical model, not a social model. The balance of resources has gone into diagnosis and not into early intervention or family support (Appendix 2)'. Likewise, Autism Initiatives indicated during oral evidence on 13 January 2011 that it supported an autism strategy across the full range of Government departments and activities: 'There is a level of co-operation, but, particularly at a time of acute financial difficulty, it is much easier for other Departments to prioritise other areas or reduce services in some areas. A legislative commitment would make it more difficult for that to happen. That is one of the main reasons why we support that approach (Appendix 2).' However, other groups expressed concerns about the legislative requirement for an autism strategy including the DHSSPS, RASDN, the HSC Board, the Human Rights Commission, The Parent Carers' Council on Disability, a number of the Education and Library Boards, the Equality Commission, and a number of the HSC Trusts. For example, during oral evidence on 16 December 2010 the Regional Autism Spectrum Disorder Network indicated that co-operation between agencies already existed without the need for legislation: 'The board believes that integrated planning across agencies and Departments is critical to meeting the wide-ranging need of anyone with a disability, including people with autism, as a principle. An example of that is through children's services planning, which is a mechanism that we employ. Currently, there is no statutory duty to co-operate under children's services planning, but we have an effective, multi-agency planning system that has been running for nearly 12 years (Appendix 2)'. The Regional Autism Spectrum Disorder Network Reference Group supported this view and in its written submission stated: 'The Department has already carried out an Independent Review of Autism Services and is a year into implementing the Review's recommendations. It is, literally, involving parents, carers and users at Trust level in all aspects of service provision including 'commissioning'' (Appendix 3). After considering the evidence the Committee came to the view that a legislative requirement for all government departments to co-operate in the production of an autism strategy was a positive step forward. It was the Committee's view that without legislation it would be difficult to ensure that departments other than health and education fully participated in the strategy. Cost of an Autism StrategyIn terms of the content of the autism strategy, a number of stakeholders raised concerns in relation to the potential financial implications. The DHSSPS had specific concerns regarding the costs associated with clause 3 (5) which deals with the provision of autism awareness training for civil servants who deal directly with the public. The Department indicated in its written submission: 'Training for civil servants brings a potential cost of some £1.8m (based on circa 25,500 civil servants at £65 per head)' (Appendix 3). Likewise, the Minister for Finance & Personnel raised the matter of cost in his written submission which stated: ' I share Mr McGimpsey's concerns particularly about the lack of information on costs and the absence of a finance clause taking account of direct and wider impacts on funding (Appendix 3)'. Similarly, the Aspergers Network in its written evidence stated: 'No financial effects are available, and considering the Bill requires public servants, who deal with the public are to be trained; at what cost. Will these costs be removed from the recent increase in Trust services for families? Or would there be a decrease in the new Autism related jobs within Trusts? (Appendix 3)'. However, other groups such as Autism NI made the counter argument and suggested that a cohesive autism strategy may reduce costs: 'With an effective cross-departmental strategy, with good strong leadership at the head, the potential for cost saving through reduction of duplication is incredible (Appendix 2)'. During his oral evidence on 20 January 2011, Mr Bradley disputed the Department's estimate of the cost of training civil servants: 'I presume that some of that cost is already being met by the system, because public servants in the Department of Education and the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety already receive some autism training. A level of training is probably provided by other Departments, such as the Department for Social Development, although that may not be sufficient. That might be the global figure for the overall costs, but, as I said, some of that is already being incurred by Departments. There may be an extra cost, but it would not be at the level of £1·8 million (Appendix 2)'. Mr Bradley further indicated during his evidence on 20 January 2011 that he was considering an amendment to change the reference from "civil servants" to "public servants". In response, the Minister for Health, Social Services & Public Safety wrote to the Committee in a letter dated 27 January 2011 to express the following concerns: 'My Department does not hold figures for public servants for the whole of NI; however for health and social care, there are approximately 71,300 public servants (at 31 December 2010). This proposed amendment would, therefore, increase this potential cost to circa £4.6m for this Department alone; this takes cognizance of the fact that some staff have already been trained in autism awareness. This does not include, PSNI, Council workers, teachers, bus drivers etc. who would be included in the figures from other Departments' (Appendix 4). When Mr Bradley was made aware of these concerns he subsequently wrote to the Committee to advise that he intends to withdraw clause 3 (5) from the Bill completely (Appendix 4). The Committee was content with this amendment. Summary of EvidenceGeneral CommentsIn considering the Bill, the Committee took account of the written and oral evidence received from the range of stakeholders who responded to its call for evidence. It also took oral evidence from the Sponsor of the Bill, Mr Dominic Bradley MLA, who provided additional information and clarification on the points raised in the submissions received. The evidence received and considered by the Committee was wide-ranging and the views of organisations differed considerably towards the Bill. Many organisations welcomed the Bill in its entirety, however others had concerns with particular clauses, while some groups opposed the Bill completely. Clause 1: Amendment to the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995A broad spectrum of evidence was received on clause 1 of the Bill which seeks to amend both the definition of disability as set out in the DDA and the list of "normal day to day activities" contained in Schedule 1 of the DDA. In overall terms, some organisations supported this clause because they took the view that it would enhance the ability of those people with ASD to claim protection under the DDA. However, other groups held the opposite view and argued that any changes to the DDA could potentially exclude those same people from its protection. The groups which supported clause 1 included Autism NI, the Human Rights Commission, Autism Initiatives, Action for Children and the Parent's Autism Lobby (PAL). Their view was that the addition of the words "social (including communication)" to the existing definition of disability as a "physical or mental impairment" would allow more people with ASD to be recognized as having a disability, and that this would enhance their access to services and benefits. Likewise, they believed that the extension of the list of "normal day to day activities" would help resolve any ambiguity as to whether the DDA covers people with ASD. These stakeholders explained to the Committee that in their experience some government agencies relied on the DDA when assessing whether a person with ASD was entitled to various benefits, including Disability Living Allowance (DLA). The feeling was that the DDA in its present form does not provide sufficient clarity to decision makers on whether ASD falls within it. The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission came at the issue from a slightly different position. They supported the amendment to the definition of disability to include social and communication impairments. It was their view that given that the state has endorsed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability's use of the social model of disability, the statutory definition should also reflect this position. However, other organisations expressed serious concerns about the changes proposed to the DDA in the Bill. These included the DHSSPS, RASDN, the Reference Group of RASDN, the HSC Board, Aspergers Network, the Equality Commission, a number of the Education and Library Boards, Carers NI, the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, the Royal College of General Practitioners, and a number of the HSC Trusts. The DHSSPS, RASDN and the HSC Board contended that the definition of disability within the DDA already covered people with ASD, and that the term "physical or mental impairment" was intended to be all-encompassing. The Aspergers Network took a similar stance and argued that to alter the definition of disability under the DDA may undermine the legal status of the DDA completely. Likewise, the Equality Commission advised that it was not aware that the definition of disability in the DDA had caused particular difficulties for people with autism accessing their rights under the legislation. The DHSSPS also argued that amending the DDA as proposed by the Bill would not have the effect of increasing access to benefits such as DLA for those people with ASD. A research paper prepared for the Committee provided further information on this issue and made the point that the DDA only provides protection to those people who meet its definition of disability. This definition of disability is not applied within the benefits and tax credits systems (Appendix 4). In terms of the education sector, a number of groups were concerned that clause 1 could give rise to possible conflicts with Special Educational Needs (SEN) legislation. The Department of Education advised the Committee that it was currently examining the potential impact of the Autism Bill on the current SEN legislation in terms of whether the Bill might give priority to children with autism over children with other SEN. However, they did not reach a conclusion on this matter before the completion of committee stage (Appendix 4). The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists objected to clause 1 on the basis that it may further discriminate against individuals with a communication disability who do not have a social communication disability. Towards the end of its period of evidence taking, the Committee considered a research paper which noted that a view had been put forward in other jurisdictions that to amend the term "physical or mental impairment" could in fact narrow the scope of people who could fall within the definition of disability (Appendix 4). In terms of the proposed amendment to the list of "day to day activities", the research paper advised that a consultation document had been published on guidance for defining disability within the context of the Equality Act 2010 (Appendix 4). The consultation paper included the following day to day activity – "Significant difficulty taking part in normal social interaction or forming social relationships". The Committee noted that this wording was very similar to what was being proposed in clause 1 (3) of the Bill. When the Committee took evidence from Mr Bradley on the Bill, it raised the issues of concern relating to clause 1. Mr Bradley advised the Committee that he had further considered the issue of amending the definition of disability and had come to the decision leave out clause 1 (2) from the Bill. Mr Bradley then confirmed his position in writing to the Committee (Appendix 4). The Committee welcomed Mr Bradley's amendment to the Bill. In terms of clause 1 (3) which amends the list of "day to day activities" in Schedule 1 of the DDA, the Committee noted that a similar approach was being taken in relation to the guidance being developed for the Equality Act 2010. The Committee was therefore content with clause 1 (3) of the Bill. Clause 2: Autism StrategyAs with clause 1, opinion was divided amongst stakeholders on the merits or otherwise of legislating for an autism strategy. Those who supported this clause made the general argument that legislation is required to ensure that all government departments work in a joined up manner to produce a comprehensive strategy to deal with ASD. However, other organisations took the view that the current autism strategies being delivered by the DHSSPS and the Department of Education were working well, and that to create a new strategy would result in more bureaucracy. Furthermore, they argued that designing a new autism strategy would be costly in terms of time and money, and that resources would be better spent to provide services for people with ASD. The groups which supported clause 2 included Autism NI, the College of Occupational Therapists, Autism Initiatives, Action for Children, Carers NI and the Parent's Autism Lobby. Autism NI made the point that in relation to the current strategies being delivered by the DHSSPS and the Department of Education, there is limited buy-in from other departments. Autism Initiatives stated that making it a legislative requirement for departments to produce a joined up strategy on autism would be valuable, particularly at a time of public spending cut-backs. PAL stated that currently there was a lack of co-ordination between departments in relation to ASD which has resulted in both duplication and gaps in some services. However, other groups expressed concerns about clause 2 including the DHSSPS, RASDN, the HSC Board, the Human Rights Commission, The Parent Carers' Council on Disability, a number of the Education and Library Boards, the Equality Commission, and a number of the Trusts. The Equality Commission stated that while it is in favour of a cross departmental action plan, with actions, timescales and performance indicators, it is not convinced that there is clear need for the DHSSPS to be placed under a statutory duty to prepare a strategy on autism. Likewise, the BELB and NEELB support the need for interdepartmental and multi-agency co-operation in order to achieve a co-ordinated autism strategy, but were concerned that ASD specific legislation in relation to children could advertently discriminate against all other children with special needs. They suggested that the Bill be restricted to adult services only as has been done with the Autism Act 2009 in England. The DHSSPS argued that from a policy perspective, it remains uncertain what the proposed strategy is designed to do, especially since there is already in place an ASD strategic action plan and an infrastructure to deliver it. This stance was also taken by the HSC Trusts. The Department also pointed to the issue of cost, and stated that it might be argued that the Bill's intent is to improve rights of individuals and their carers to have needs met and that this could not be achieved without significant cost. RASDN made reference to the work it was already carrying out in terms of its ASD strategy and stated that they already work on a multi-agency basis. In their view this is recognised good practice and legislation is not required to force them to do it. The Reference Group of RASDN stated that the current strategy is working and progress is being made. After considering the evidence the Committee came to the view that a legislative requirement for all government departments to co-operate in the production of an autism strategy was a positive step forward. It was the Committee's view that without legislation it would be difficult to ensure that departments other than Health and Education fully participated in the strategy. The Committee agreed that it was content with clause 2. Clause 3: Content of the Autism StrategyAs with the previous two clauses, opinions were divided on clause 3. A number of organisations including Autism NI, Action for Children, the Parent's Autism Lobby, and the National Autistic Society supported clause 3. They argued that it was important that the strategy addresses the needs of people with ASD throughout their lives from childhood through to adulthood. They drew attention in particular to the key transition issues facing people with ASD, when they make the move from childhood towards adulthood and independence. However, other organisations highlighted concerns regarding clause 3 such as the DHSSPS, the College of Occupational Therapists, Education and Library Boards and Autism Initiatives. The DHSSPS stated in their evidence to the Committee that some concern has been expressed that the Autism Bill might possibly be subject to challenge under the European Convention on Human Rights, particularly in relation to individuals and families living with other significant disabling conditions. However, the Department did not provide any further information on what basis it was postulating this view. A number of groups, including the Education and Library Boards, took the view that an autism strategy should only apply to adults. They suggested that if the autism strategy relates to children and young people it may give rise to complexities and possible conflicts with existing SEN legislation. The Committee raised an issue with Mr Bradley in relation to clause 3 (2) in terms of the use of the word "social". The Committee questioned whether the term "social" needed to be expanded upon, to ensure that issues such as the employment or housing needs of people with ASD were covered in the strategy. Mr Bradley wrote to the Committee to advise that he had taken advice on the interpretation of clause 3 (2) specifically relating to the possible advantage of elaborating on the meaning of the term "social" to include "employment, leisure, housing, etc". His advice was that clause 3 (2) must be read in light of the general overarching obligation in 3 (1). Clause 3 (2) therefore begins "Without prejudice to the generality of subsection 1" to clarify that these issues highlighted are not to diminish the wider obligation. In his view no specific amendment is required as the overall interpretation of clause 3 (2) is inclusive (Appendix 4). The DHSSPS also raised the issue of cost and queried the fact that Mr Bradley had stated that the Bill would have no significant costs. The Department pointed to the fact that the cost of formulating a rolling and indefinite autism strategy is not specified, nor is the need to establish extensive monitoring arrangements. The Department of Finance and Personnel also expressed a concern about the lack of information on costs and the absence of a finance clause in the Bill taking account of direct and wider impacts on funding. However, other groups such as Autism NI made the counter argument and suggested that a cohesive autism strategy would not only stop wasteful duplication of some services, but through appropriate interventions and support greatly reduce future costs on society as individuals and families are empowered to support themselves. The DHSSPS had specific concerns regarding the costs associated with clause 3 (4) which requires it to set out proposals for promoting an autism awareness campaign, and clause 3 (5) which deals with the provision of autism awareness training for civil servants who deal directly with the public. The Department advised that it had developed its own indicative costs. In relation to training for civil servants, the Department quoted a potential cost of some £1.8m (based on circa 25,500 civil servants at £65 per head). In relation to the potential cost of public awareness-raising, the Department quoted figures ranging from £25,000 for a small advertising campaign to £235,000 for a wider campaign encompassing limited TV, press, online and radio adverts. Autism Initiatives also had concerns with costs, and stated that they would prefer to see the resources directed at a public awareness campaign and training for civil servants go to frontline services. In their view awareness raising and training could be carried out as part of general disability awareness campaigns. The Committee was concerned with clause 3 (5) in terms of its reference to "civil servants". The view was that there were other public sector workers who delivered frontline services in health and social care and education who would benefit more from autism awareness training than civil servants would. Mr Bradley subsequently wrote to the Committee to advise that he intends to withdraw clause 3 (5) from the Bill completely (Appendix 4). The Committee was content with this amendment. Clause 4: InterpretationThe Committee received few comments in relation to this clause. The Education and Library Boards stated that as the terminology surrounding autism changes and will continue to change over time, the Autism Bill should adopt a similar approach to the Autism Act 2009 by not including the definition of autism in the primary legislation. The Committee agreed it was content with the clause. Clause 5: Regulations and Orders made under this ActThe Committee did not receive any comments in relation to this clause. Clause 6: CommencementThe Committee did not receive any comments in relation to this clause. Clause 7: Short TitleThe Committee did not receive any comments in relation to this clause. Clause by Clause Consideration of the BillThe Committee undertook its clause by clause scrutiny of the Bill on 27 January 2011 – see Minutes of Evidence in Appendix 2. Clause 1: Amendment to the Disability Discrimination Act 1995The Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted subject to the proposed amendment agreed with the Sponsor of the Bill to withdraw clause 1 (2) which amends the definition of disability in the 1995 Act. Clause 2: Autism strategyThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted. Clause 3: Content of the Autism StrategyThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted subject to the proposed amendment agreed with the Sponsor of the Bill to withdraw clause 3 (5) which deals with autism awareness training for Northern Ireland Civil Service Staff who deal directly with the public. Clause 4: InterpretationThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted. Clause 5: Regulations and Orders made under this ActThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted. Clause 6: CommencementThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted. Clause 7: Short TitleThe Committee indicated it was content with the clause as drafted. Long TitleThe Committee indicated it was content with the long title of the Bill as drafted. Appendix 1Minutes of ProceedingsThursday, 14 October 2010

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mr Dominic Bradley MLA |

All-Party Assembly Group on Autism Secretariat |

1. The Chairperson (Mr Wells): With us today are Dominic and Arlene, both of whom have been before the Committee on several occasions. Although Dominic Bradley needs little introduction to anyone in the room, he is an MLA for Newry and Armagh and chairperson of the all-party Assembly group on autism (APAGA). Arlene Cassidy is a member of the group's secretariat. As is usual, Dominic, you have 10 minutes in which to make an opening presentation, after which I will invite members to ask questions on the draft private Member's Bill.

2. Mr Dominic Bradley (All-Party Assembly Group on Autism Secretariat): Thank you for the opportunity to present evidence to the Committee on the draft autism Bill for Northern Ireland. We have been before the Committee on one previous occasion, and I am pleased to say that we have advanced the proposed Bill since then. The Committee has a copy of the draft Bill, and we intend to make few further changes to it. A single word or phrase here and there might change, but any further changes will be minimal.

3. I am the proposer of the draft Bill on behalf of the all-party group on autism. Arlene Cassidy is the chief executive of Autism NI and provides secretarial services to the group. Some members of the Committee, including Michelle O'Neill, are also members of the group. We sent a copy of our presentation to the Committee earlier, and it illustrates the tension between the unprecedented and rapid rise in the prevalence of autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) and the limited resources that are available to meet the resulting needs.

4. The case that I wish to put to the Committee today is that the historical failure to prioritise autism appropriately is compounded by the failure of existing legislation to recognise the disability. The draft Bill addresses that anomaly. To ensure that ASD is included, it amends the definition of disability in the existing Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995 by inserting: "social (including communication)". The draft Bill, therefore, provides more clarity for the Departments and public bodies that use the DDA definition of disability as guidance when making decisions, for example, on disability living allowance.

5. The measure will profoundly affect families because it will accord recognition to a challenging condition that has been low in the hierarchy of disability in our society. When implemented across public bodies, it has the potential to improve the public understanding of issues that face individuals with ASD, such as access to services and buildings. Significantly, it will signal the beginning of the end of discrimination against individuals with ASD who have an IQ of above 70.

6. The draft Bill directs the establishment of a cross-departmental approach to ASD by requiring the development of a cross-departmental or government strategy for autism led by the Health Department. As I said, the historical failure to recognise ASD has resulted in a legacy of underfunding across Departments, and, as the amendment to the DDA takes effect, all Departments will, inevitably, have to address the impact of legislative change to their policies, practice and provision. Clause 2 creates the requirement to undertake that exercise together in an effort to minimise duplication and maximise effectiveness. I presume that there is consensus on the view that the development of a single departmental ASD strategy by the Health Department and, more recently, by the Education Department stands in sharp contrast to the joined-up realities of life as one transition leads to another across home, education, employment and community.

7. Given the climate of economic constraint, it is incumbent on all of us to plan smartly for future challenges. A cross-departmental commitment to joint planning for ASD is not only good practice, it also provides an opportunity to look afresh at existing resources and how they could be used or redeployed. It also challenges Departments to work innovatively with the voluntary sector to maximise the accountability, flexibility and creativity of all sectors.

8. The draft Bill addresses the issue of scrutiny. Just as there is an equality and financial balance to be struck between the entitlement to services and their cost, so there is a balance between the processes of accountability and bureaucracy. That clause recognises that challenge by placing a duty on the Minister of the designated lead Department to report to the Assembly every two years on the progress of the autism strategy.

9. The proposal to establish an autism advocate has been withdrawn, but it can be introduced in the future should the need arise. The withdrawal of the autism advocate from the Bill is a decision that we made in light of the present pressures on resources. The current accountability mechanisms, including this and other statutory Committees, along with the requirement of the Minister to report to the Assembly biennially will ensure accountability for the strategy. In light of the huge pressures on resources, the decision to withdraw the autism advocate is a responsible one.

10. After the all-party group's previous evidence session to the Committee on 17 September 2009, representatives from the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety raised concerns about the proposed legislation when they gave evidence on 1 October 2009. Their concerns focused on the perceived cost of the implementation of an autism Bill and on the impact that such legislation would have on other disability groups. It is our duty to listen to all views, as has been the policy of the all-party group since its inception in 2008, which was in response to the campaign led by families committed to change.

11. More recently, the consultation on the proposed legislation was conducted across a wide range of statutory and voluntary agencies and resulted in a positive rating of between 70% and 80%. Follow-up meetings were held with the Equality Commission, the Children's Commissioner and Disability Action. Those meetings resulted in agreed positions on the potential benefits attached to the introduction of the legislation in providing and enhancing clarity. In addition, the Northern Ireland Local Government Association (NILGA) and most of the 26 local councils passed unanimous motions in support of the draft Bill.

12. It is our position that the all-party group has, therefore, addressed the concerns expressed by the Department of Health, Social Services and Public safety and that the proposed autism Bill is deserving of support. We welcome the opportunity to present to you, and we would also welcome feedback from Committee members. I will finish there, and, once again, thank you for the opportunity to present our case.

13. The Chairperson: Thank you, Dominic, for your extremely helpful presentation. I would like clarification on a few points. Initially, there was a discussion about ring-fencing funding for those who have autism and those who care for them. That does not seem to feature in this draft. Was that an idea that was floated but did not come to anything? What is the position on funding?

14. Mr D Bradley: I will ask Arlene to respond to that.

15. Mrs Arlene Cassidy (All-Party Assembly Group on Autism Secretariat): Thank you. I remember the issue of ring-fenced funding as one of the three key messages of the political lobby that was led by Autism NI. In 2006, the three key aspirations of the political lobby were ring-fenced funding for autism, a cross-departmental strategy and an impact on legislation. Those were the aspirational goals of a political lobby; they were not signed up to per se by the all-party group.

16. The Chairperson: Does this draft Bill still leave it in the Minister's power to allocate funding for autism services as he deems appropriate?

17. Mr D Bradley: It will be the Minister's duty to co-ordinate the strategy across several Departments. Naturally, the Minister would not have power over any Department other than his own, but there would be a duty on him to provide the best possible services through the strategy and to meet the needs of those services with appropriate resources.

18. The Chairperson: Does any provision enable the Minister to do something that he cannot do currently should he so wish?

19. Mr D Bradley: Yes. At present, the Minister would probably find it difficult to formulate a cross-departmental strategy, as it would depend on the willingness of other Ministers to participate in and agree to it. From that perspective, the draft Bill gives the Minister added strength. It means that he does not have to depend on the goodwill of other Ministers, but that other Ministers are obliged to co-operate with him in formulating the strategy. From the point of view of the Health Minister, the draft Bill adds something to his armoury in relation to co-operation and linkages with other Departments.

20. Mr McCallister: Welcome, Dominic and Arlene. The Chairperson made a point about co-operation between Departments, and it will be no great surprise to the two of you, or to anyone around the table, to hear of my concerns about Middletown. How do you envisage the Minister linking into such a situation? It could almost be said that there is a divergence between the health and education policies on an autism strategy. This draft Bill does not give the Minister the power to intervene or to obtain resources from another Department. That concern is linked to some of the Chairperson's concerns about what the legislation will enable the Minister to do that he cannot do now. Even under the provisions of the draft Bill, he could not develop a strategy or demand resources if his plan was at odds with what the Minister of Education wanted to do.

21. Mr D Bradley: The Minister will outline what he believes to be an effective strategy, and the onus will be on other Departments to provide the resources to implement it.

22. Mrs Cassidy: If it is to be a cross-departmental strategy with a required sign-up by the other Ministers, all resources and plans would have to be reconciled. The other Ministers would be accountable to the Assembly should they not progress that strategy.

23. Mr McCallister: There could be potential difficulties with that because the structure of government means that all the Ministers might change next May. However, there the divergence in policy may remain, which could result in a worse position in which nothing happened. If the consensus that is required between Departments cannot be achieved, we could be left with a situation in which little or nothing happens, or, indeed, with a strategy that is weaker than what exists at present.

24. Mr D Bradley: That is probably the worst-case scenario. I do not choose to look at it that way. If that is an issue that needs to be addressed, we will certainly consider it. The Bill is still in draft form, and if there is a mechanism to overcome that scenario, we would welcome your views on it. All legislation must take account of the worst-case scenario and ensure that all possible loopholes are closed. I welcome the fact that you have apprised us of the issue.

25. The Chairperson: You have deleted the reference to an autism advocate, but left the door slightly ajar in the sense that it could be reconsidered. Would that require primary legislation, or does any provision in the draft Bill enable that to happen by way of a statutory rule or subordinate legislation?

26. Mr D Bradley: There is no such provision in this draft. You raised a good point; perhaps we need to consider including a reference to the autism advocate in the draft Bill. We did not do so because we considered that the accountability mechanisms in the Assembly should be strong enough to ensure the implementation of the strategy. Nevertheless, I note your point, which is useful, and we will consider it further.

27. Mrs O'Neill: I declare an interest as a member of the all-party group on autism. Another possibility is that there would be nothing to stop the Department, as part of the overarching strategy, proposing an advocate to oversee that strategy.

28. The Chairperson: However, for that person to be at the level of, for example, a commissioner would require primary legislation. We cannot simply decide that there will be an older people's commissioner or a children's commissioner; we have to go through all the required legal procedures. Bills were required to establish both of those posts.

29. Mr D Bradley: That is one reason why we have not included the advocacy role at this stage. The start-up costs would be considerable, and it would probably take a year or more to establish the office of advocate and its operation. As I said, we have not ruled out completely the role of advocate, and I take your point, Chairperson, that if consider it to be a future possibility, it may be judicious to include some opening in the draft Bill to facilitate it.

30. The Chairperson: That is a double-edged sword, because some people are keen on the idea of an advocate, and others are concerned about it. Its inclusion in the draft Bill as a potential option for the future may cause difficulties for some people, particularly given the current economic situation.

31. Mr Easton: As you know, I support a Bill for autism. I am not having a go at you, but I am a wee bit disappointed that it has been watered down, although, to an extent, I understand why. Was it watered down to heal the relationship with the Department, which was unhappy at the prospect of an autism Bill?

32. I am pleased that the Departments will be forced to work together to come up with strategies. However, I am disappointed that extra funding may not be forthcoming from those Departments, because I believed that we would force them to contribute. Therefore, although I am happy that the Departments will work together, I am disappointed that there will be no additional funding and that the advocate idea will not be progressed. Nevertheless, I will continue to support you.

33. Mr D Bradley: To a large extent, I share your disappointment. The dilution or watering down of the draft Bill was not a result of interaction with or feedback from the Department. We took the temperature of some of the parties, and the feedback was that resource implications might make it difficult to move the legislation through the Assembly should it include the position of advocate or commissioner. We thought that such an inclusion would, perhaps, lead to the proposed Bill's not becoming an Act. Although we regretted doing so, we had to balance one element against another, and, with the support of the all-party group, we decided that it would be better to progress the key elements of the legislation and that the advocate's position should be held in reserve for the future.

34. Mr Easton: I suppose that it is better to bank what we can now and work towards achieving more later.

35. Mrs O'Neill: As you know, I strongly support an autism Bill. When the Committee wrote to the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) about changing the DDA to include social communication disability, its response was that there was no need to do so. Looking ahead to the Committee's scrutiny of the legislation, I assume that officials of OFMDFM and the Health Department will attend as witnesses. Will you explain why the DDA needs to be changed and why people with a social communication disability are not protected by it at present?

36. Mr D Bradley: One practical reason is that Departments use the DDA as guidance when, for example, awarding disability living allowance. Consequently, people with autism have not benefited from the guidance. Arlene will expand on that point.

37. Mrs Cassidy: I have a list of issues that may be useful in helping people to get their heads round the implications of amending the DDA. The systematic education of the public that would flow from the adaptations to public spaces and facilities; the emotional hook of ASD being recognised in law would bring a level of validity regarding a condition that is still treated with suspicion and ignorance by some professionals and agencies; and clarity in law is a practical benefit that would guide decision-making on benefit entitlement. I will elaborate on the third point: some DLA adjudicators have disallowed benefits because a child's condition of autism did not fit with the definition of disability that appears in the DDA. We can present such decisions as evidence in support of our case. Such legal clarification will also lead to the updating of disability action plans for public bodies and an improvement in access to equality legislation. Families will have a reference point for entitlement to services, such as those for people with autism whose IQ has been assessed as 70 or above. Finally, the physical adaptations to public buildings will assist not only those with ASD but the wider disabled community.

38. Mrs O'Neill: I am on board with the change to the DDA. I thought that it would be useful for the Committee also to be aware of the implications, because we will have to deal with the counter-arguments. The fact that a commissioner, or whoever was involved in the tribunal process, refused someone a benefit because autism did not fit is a powerful argument and just what we need to drive through the legislation. You mentioned that you have evidence of such cases. It would be great if you could provide that to the Committee.

39. Another issue is that the Health Department might say that it already has a strategy in place. Will you comment on how your strategy will differ?

40. Mr D Bradley: The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety has an action plan on autism, and the Department of Education is formulating a strategy on autism. In a way, that illustrates the need for strategies to be streamlined between Departments. Indeed, some Departments that need such a strategy do not have one at all.

41. We welcome the Health Department's action plan. It can fit into and become part of the legislation. The draft Bill does not negate that action plan, but encourages its integration with strategies in other Departments. In that way, the services that people with autism receive can be streamlined between Departments and between the various transitional stages of their lives.

42. Mrs Cassidy: I noted a few points that might be helpful to the Committee. By recognising in law the requirement for cross-departmental planning, buy-in and synchronicity, an autism Bill will make a real difference to families. As Dominic indicated, the strategy will assure families that government recognise the lifelong and whole-life reality of autism. Through shared funding initiatives across Departments, it also assures the potential for service development during harsh economic times. The strategy identifies autism is a shared responsibility in our community. It means that duplication and confusion can be addressed and transitions, which are uniquely distressing for individuals with autism, can be better planned and resourced.

43. The Chairperson: I may be playing devil's advocate again, but why do other conditions, which are sometimes complex and have implications that cross several Department, not demand a similar Bill and treatment?

44. Mr D Bradley: Perhaps some of them do. The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety considers that autism requires an action plan. Indeed, it has formulated such an action plan and set up original reference groups to deal with that. That Department agrees that there is a need to focus on autism and to undo its history of neglect. The Department of Education also set up a task force on autism, yet it did not establish a task force on any other disorder or disability. It is also formulating a strategy on autism and agrees that action must be taken to tackle the ignorance that surrounds autism and to undo its historical neglect.

45. The Health Department and others argued that it was wrong to focus on one particular disorder or disability. However, both the Health and Education Departments have adopted a focus on autism.

46. Mr McCallister: My question about the potential risk was on the same lines as that of the Chairperson. Given your reply to the Chairperson, is there any risk involved in having an autism Bill? The Health Department has, for example a stroke strategy, but we do not legislate for that. I also have concerns about autism and any sort of special need that is difficult to identify in young children. I have dealt with some statementing issues in my constituency. Will legislation take autism to a level at which it is almost advantageous for a child to have had the condition diagnosed when attempting to acquire a statement of educational need? Do you regard that as a risk inherent in setting autism on a different level from other conditions or needs?

47. Mr D Bradley: No. You described a scenario in which parents might regard a diagnosis of autism as a means of obtaining a statement of educational need. I do not consider that to be a danger connected to the legislation. Most parents to whom I have spoken, and I am sure that you have spoken to many in your constituency office, do not rejoice when their child receive a diagnosis of autism. In fact, some of them go into denial. Parents say that they wish that their child did not have autism and had been diagnosed with a less challenging condition. No parent wants a child to receive an inaccurate or irrelevant diagnosis of autism. Based on our evidence of parents' reaction to such a diagnosis, that is not the case.

48. Mrs Cassidy: That goes back to the core issue of an autism Bill, which is the amendment to the Disability Discrimination Act. The current definition refers to disability as physical or mental, and, under the latter, to learning disability and mental illness. As autism is none of the above per se, but can be any of the above, it is not included. As I said earlier, much flows from its non-inclusion. That is a fundamental flaw in our system, and we hope that other equalities will flow from its redress to afford autism equality with other disabilities. We want equality for autism, not for it to be regarded as something special or above other conditions.

49. Mr McCallister: If I may widen the scope, autism is a developmental illness that does not fit neatly into any category.

50. Mrs Cassidy: As you know, autism involves social and communication impairment, and the intention is to include wording to reflect that in the amendment to the DDA. There is a precedent for the DDA being amended, as it was to include conditions such as cancer and HIV. We are bringing the DDA up to date to make it relevant to today and to what we know about autism.

51. Dr Deeny: I have a couple of questions, the answers to which might not be a simple yes or no. Does autism require a specific Bill? The Chairperson asked why we should not have specific Bills for other conditions. Is legislation for autism required because of the problems that have arisen from it not falling directly under a single remit but crossing the remits of health and education?

52. Arlene, GPs see a wide range of ASD in their practices. A couple of patients in my practice are highly autistic, and it would take a specialist to tell that others are autistic at all. Is the width of the spectrum a problem?

53. You mentioned that people with autism who have a high IQ are excluded from gateway services.

54. Mrs Cassidy: The issue of the IQ level is a current one. The situation is that a child with autism who has a co-existing learning disability can access services through the learning disability services. Children with autism who do not have a learning disability cannot access child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) if their IQ is 70 or above, unless they have a co-existing mental illness. The Southern Trust has made some strides in that respect, but I know from parents' experiences in many other trusts, an IQ of 70 or below was required to access the gateway to services.

55. Dr Deeny: Does an IQ of above 70 exclude children from access to those services?

56. Mrs Cassidy: Yes.

57. Dr Deeny: Does that tie in with the severity of ASD? Some people with autism are severely affected, and, in many cases, their IQ cannot even be assessed.

58. Mrs Cassidy: I can give only my perspective. As recently as 15 years ago, many people believed that someone with autism also had a learning disability. The statistics were that 75% of people with autism had a learning disability and 25% did not. We now know that the true position is exactly the reverse, and we have a better understanding of what life is like for those individuals who have an IQ of above 70. Many people consider that those with an IQ of above 70 cope better, but their families have to deal with a different set of severe difficulties.

59. In answer to your other question, the width of the autistic spectrum has become an issue as our understanding has grown over the years. An autism Bill aims to bring us up to speed. Our knowledge of autism and its prevalence have shot through the roof. The current system is creaking in an attempt to meet the accelerating need. The legislation aims to create a foundation on which we can build.

60. Mr Gallagher: I support the draft Bill and acknowledge the work that has gone into it. We are trying to achieve a seven-year strategy that will be published by the Department. The idea is that the trusts will feed into the strategy and provide the resulting data to the Department. Arlene, you said that autism rates are rising and rising. Do you envisage the trust providing that data every seven years or annually? Have you decided on that yet? Everyone agrees that the rate of autism is rising? Have you considered whether that data should be collected by the trusts every seven years, or should that be done every year so that the Department has the up-to-date data on its desk?

61. Mrs Cassidy: Data collection for planning purposes has to be done annually. The education and library boards collect data on school-age children with autism. A couple of weeks ago, at an event here, a colleague from the Belfast Education and Library Board told me that the prevalence rates that Autism NI was quoting, of one in a hundred, were out of date. I said that I knew that they were conservative but that we did not want to send out the message that the condition is more prevalent than it is. He quoted a rate of one in fifty in Northern Ireland, and we are now seeking to confirm that.

62. The cross-departmental issue of data collection in the draft Bill focuses more on synchronising the data collection of the Health and Education Departments. The Department of Education has a track record in data collection, but the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety has not and is addressing that in its action plan. I cannot report to the Committee on how far that work has progressed, but data collection has been flagged as an issue. The aim is to synchronise such effort to improve cross-departmental planning.

63. Mr D Bradley: If Tommy was suggesting that it would be useful for information to be updated much more regularly, I agree. It is hoped that the strategy will not remain static over the seven years, but that it will be sensitive and adjusted in response to information fed back from the statistical report.

64. The Chairperson: Any autism Bill will undergo a Committee Stage, so we will have plenty of opportunity to scrutinise it then.

65. Thank you very much, Dominic and Arlene, for your evidence. The Committee will probably see a great deal of you in connection with the legislation over the next few weeks and months.

66. Mr D Bradley: I thank the Chairperson and Committee members for engaging with us today. Although some of the points raised were quite challenging, they were useful and constructive. They will be helpful to us as our work on the draft Bill continues.

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Jim Wells (Chairperson)

Mr Pól Callaghan

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Tommy Gallagher

Mr Sam Gardiner

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr John McCallister

Witnesses:

Dr Maura Briscoe |

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety |

67. The Chairperson (Mr Wells): We have with us representatives of the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. Some of the faces will be familiar to the Committee. Dr Maura Briscoe is the mental health and disability policy director, and has been before us on several occasions to address various issues; Dr Ian McMaster is a medical officer in the Department; Dr Hilary Harrison is a social services officer in the Department; and Peter Deazley is from the Department's learning disability unit. Please give the Committee a 10-minute presentation on the Department's position on the Bill.

68. Dr Maura Briscoe (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety): Thank you very much, Mr Wells. Good afternoon, everyone. We fully recognise the importance of autism. We have, through various mechanisms in the Department, tried to promote and enhance autism services for children and adults, particularly over the past few years, and we will continue to do so. Therefore, on that basis, we believe that legislation is unnecessary at this time. I will drill down into the detail of why we think that it is unnecessary. Before I do that, however, I highlight that there has been substantial investment over the last comprehensive spending review (CSR) period. There have been a number of successes, including the formation of the regional autism spectrum disorder (ASD) network group, a significant reduction in waiting times for children for assessment and diagnosis, and the launch of a children and young people's assessment and diagnostic care pathway. The Committee will have heard the recent announcement about investment in adult autism services.

69. I do not propose to go into the detail of service provision. Rather, I will concentrate on the legislation and why the Department does not support it at this time. Members will see that the Autism Bill seeks to unilaterally change the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA) to include terms such as "social interaction (including communication)" and "social relationships". As the Committee knows, England has an Autism Act and a Bill is proceeding through the Scottish Parliament. No other jurisdiction has sought to change the UK/Westminster-enacted legislation to put in place a very broad definition in the Disability Discrimination Act.

70. Members will have seen the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) guidance for Northern Ireland on the Disability Discrimination Act. It is quite clear, and there are specific examples under DDA on autism. That is supplemented by recent case law that makes clear that autism is covered by the Disability Discrimination Act. It is unclear why the very broad definition of "significant difficulty" as:

"(i) taking part in normal interaction; or

(j) forming social relationships"

71. is being proposed to amend UK-wide legislation unilaterally in Northern Ireland. Clearly, there is a cost in doing that in respect of legal opinion, consultation, and reissuing and redeveloping guidance. There may also be challenges from individuals, for example in relation to workplaces or schools, etc, with a resultant potential cost. Given that there is already clear guidance, it is unclear why there is a proposed unilateral change in definition in the DDA.

72. The Bill also seeks to change the definition of autism. Members will note that no other UK jurisdiction has sought to define autism in primary legislation. Indeed, the Committee will have noted that Scotland considered it disadvantageous to do that because research and understanding of autism and the range of the spectrum will change over time. Therefore, that was not put in legislation. In addition, the inclusion of any pervasive disorder that is not otherwise specified in the legislation would have the potential to widen the scope of autism and, therefore, may include individuals who would not generally be considered to have autism. That may, over time, have an impact on prevalence data and the labelling of individuals with autism.

73. One of the main provisions of the Bill relates to the autism strategy. That is not in any other legislation, it is an indefinite autism strategy, and it is mandatory. That would place the Health Department in the lead position in respect of the future production on an indefinite basis of an autism strategy. Minister McGimpsey made it clear that he does not need legislation to effect change and improve ASD services. Indeed, a new strategy with a new bureaucratic infrastructure to monitor it could slow down progress in moving forward with our enhancements for ASD services.

74. Members will also note that the Department of Education is producing an autism strategy for consultation in the new year. Therefore, there is potential for confusion with the new autism strategy as defined in legislation.

75. We already have a DHSSPS autism strategy, we already have a multidisciplinary ASD regional network group, we already have a reference group that includes 30 parents, carers and service users, along with 10 voluntary organisations. The implementation of the English strategy is not a million miles away from the infrastructure that we had ahead of them.

76. The Bill also states that DHSSPS will be the lead Department responsible for monitoring all other Departments that are required to contribute to the implementation of the strategy. No other jurisdiction has that in its potential legislation. Indeed, the recent Scottish legislation mentions Scottish Ministers — plural.

77. We feel that all of that will involve bureaucracy. The requirement to monitor the rolling indefinite nature of the strategy will cost money that we feel would be better placed in front line service provision. The Bill also asks us to collect prevalence data, but we have already recognised the need to do that. We do not need legislation for that. Members will note that the recent launch of the children's care pathway on assessment and diagnosis is one step in the general direction to ensure streamlining of those services and enhanced data collection.

78. Finally, there is no detail on resources in the financial memorandum, but we feel that costs will arise from a cross-departmental strategy, the consultation process, extensive monitoring arrangements to be put in place, unilateral amendment to the DDA and from potential challenges that might ensue from those changes. Clearly, further guidance will need to be developed on the DDA. Costs will also stem from a public information campaign and to rolling out training for front line civil servants in all Departments. There will be a cost to implementing the actions in the new strategy, and that is not addressed. We would far prefer to see costs and finances going to front line services.

79. In summary, with the combination of the unilateral amendment to the DDA, a wider definition of autism, the costs and bureaucracy associated with the Bill, and the monitoring arrangements that would need to be put in place, we would far prefer to concentrate on areas where we are moving forward in partnership with what has already commenced through the regional ASD network group to improve front line services. Therefore, the Department believes that the legislation is unnecessary.

80. The Chairperson: Thank you, Dr Briscoe. On a procedural point, I may have to nip out at some point, because there is some interest in the issue of waiting lists. The Deputy Chairperson is not here, so we will have to go through the procedure of nominating an acting Chairperson. Do we have any nominations for acting Chairperson?

81. Mr Gardiner: Mr Easton.

82. The Chairperson: Mr Easton will assume that role, as usual.

83. Dr Briscoe, you made the point that, because the rest of the UK does not have such legislation, we should not have it. The view that many people would take is that we in Northern Ireland should be trailblazing, leading from the front, and trying to do our best for our autistic children. Others have not had the pioneering spirit to do this, but does that mean that we should automatically or slavishly agree with them?

84. Dr Briscoe: Not at all. We are potentially ahead of other jurisdictions in having had an ASD network group in place and a strategy in 2009, before England put through its legislation or Scotland initiated its legislation. I emphasise that broad definitions such as "social relationships" and "including communication" will have knock-on effects that will be unilateral to Northern Ireland. They may potentially cause significance, perhaps not this year, but further down the line. Do not forget that the wording is not related to autism, but to broad words such as "social interaction" and "communication", so it has the potential to widen the net.

85. The Chairperson: Autism groups have made the point that, at present, the definition of disability in Northern Ireland, physical and mental, does not necessarily cover every autistic child. The child might be all right physically and be very bright, but have enormous problems.

86. Dr Briscoe: I am happy to accept that point. I refer you to the OFMDFM guidance on the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, which clearly defines disability in the context of impairment. It specifically says that:

"It is important to remember that not all impairments are readily identifiable."

87. It goes on to list a range of them, including:

"learning or developmental difficulties such as autism spectrum disorders, developmental co-ordination disorders or dyslexia".

88. If you read through that guidance, you will see that there are at least two specific examples in relation to autism spectrum disorder. There is also case law that does not support the view that autism is not covered by the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

89. The Chairperson: I have been familiar with these processes for 30 years, Dr Briscoe. I know that there is a world of difference between a definition in legislation, and one in guidance. In legislation, a definition allows a parent to take a judicial review or court action if he or she feels that a child has not been properly dealt with. Guidance is simply that. Therefore, it much more powerful to have a specific reference in legislation that defines what is meant by an autistic child.

90. Dr Briscoe: "Social interaction" and "communication" do not define what is meant by an autistic child. I draw your attention to the fact that there is case law that clearly identifies that ASD is recognised as a disability under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

91. The Chairperson: Parents tell me that inclusion of the word "social" will guarantee that every child in the autistic spectrum will be covered. It is unusual condition: a child could be like Linford Christie with respect to his physical attributes. Some of those children are incredibly intelligent, and the ability of some of those people in maths and drawing is phenomenal but, because of their social abilities, they are different and they have problems in interacting with other children and their peers. That word guarantees that they will be covered. It ensures that no child will fall between two stools. That is what the parents are looking for.

92. Dr Briscoe: If you look at the categories in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, under schedule 2(4), it includes mobility, manual dexterity, physical co-ordination, constant ability to lift, carry or otherwise move everyday objects, speech, hearing, eyesight, memory or ability to concentrate, learn or understand, or perception of the risk of physical danger. This Bill will add underneath that the words in regard to social relationships, and so on. Therefore, only one of those categories needs to pertain, and that opens up the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 potentially much wider than was intended in the Autism Bill.

93. The Chairperson: Some children will tick all of those boxes, but they will still have incredible difficulty interacting with their peers.

94. Dr Briscoe: I draw attention to the fact that that is already covered in the guidance under:

"memory or ability to concentrate, learn or understand".

95. It gives as an example:

"significant difficulty taking part in normal social interaction or forming social relationships".

96. If there is case law and, within the definition of DDA, not only here, but across the water —

97. The Chairperson: It is in the guidance and the case law. Why not beef it up and make it perfectly clear by enshrining it in legislation?

98. Dr Briscoe: That would expand the category much wider than autism and would have potential knock-on effects with regard to protections under the DDA for a range of conditions. There are lots of conditions beyond autism that involve social impairment and social interaction. Can you imagine what that could mean in the workplace if somebody said that his or her difficulties with social interaction and social relationships impaired his or her day-to-day activities?

99. The Chairperson: It could mean that those people's difficulties might be covered by the DDA. I am merely putting the points that have been made to me. Alex Easton will take over the Chair; I will be back in five minutes. I know that members are keen to ask questions on this issue.

(The Acting Chairperson [Mr Easton] in the Chair)

100. The Acting Chairperson (Mr Easton): Does any member wish to ask a question?

101. Mr McCallister: I have a continuing concern about the Bill as it is drafted. We know that the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety has a strategy up and running, and you have said that this Bill could slow down the implementation of that strategy. How far along the track are you with the strategy? How much will it be slowed down? The Department of Education is going to take forward a strategy. There is a Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety strategy and a Department of Education strategy, a plank of which is the centre at Middletown. There is a fair divergence of opinion between the Departments. How will the Bill overcome and deal with the differing strategies of the two Departments?

102. Dr Briscoe: There is a good working relationship in the regional ASD network group between the two Departments. At local level, the regional group comprises people involved in education, and the chairperson of the ASD network, Dr Stephen Bergin, is a member of the education and library boards' inter-board ASD group. There is a good working relationship. I am not here to talk about the Department of Education's ASD strategy; I have no idea what is in it. I cannot talk about that. Our prevalence data on children and the sharing of information will be checked against any prevalence data held in the Department of Education.

103. Therefore we see, again, that on the ground there is already partnership working between health and education at all levels, so having a strategy in legislation is not going to make any difference.