Session 2010/2011

Fourth Report

Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

Report on the

Committee’s Inquiry into Participation in Sport and Physical Activity in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings, Minutes of Evidence,

Memoranda and written submissions Relating to the Report

Ordered by The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure to be printed 1 July 2010

Report: NIA 73/09/10R (Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure)

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the NI Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure and has a role in the initiation, consideration and development of legislation.

The Committee has the power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Barry McElduff (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan (Deputy Chairperson) c, g

Lord Browne of Belmont

Mr Raymond McCartney b

Mr Thomas Burns g

Mr David McClarty h

Mr Trevor Clarke d

Ms Michelle McIlveen e

Mr Billy Leonard f

Mr Ken Robinson a

Mr Kieran McCarthy

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations used in the Report iv

Report

Executive Summary

List of Recommendations

Introduction

1. Current levels of participation

2. Groups which have lower levels of participation within the adult population

3. Barriers to participation

4. Solutions

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2:

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3:

List of Written Submissions to the Committee

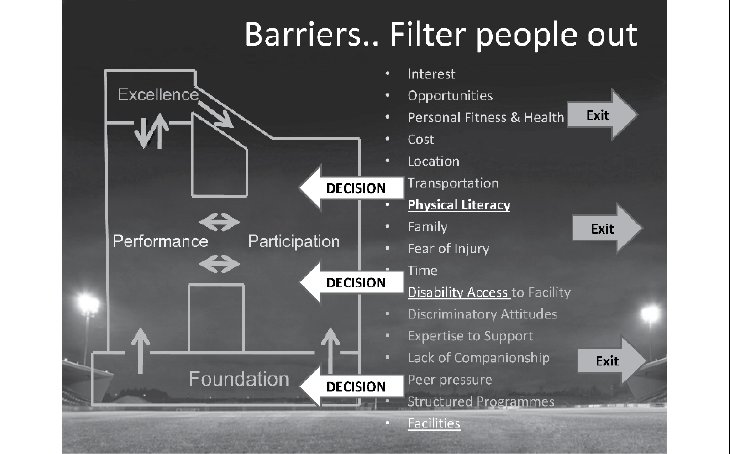

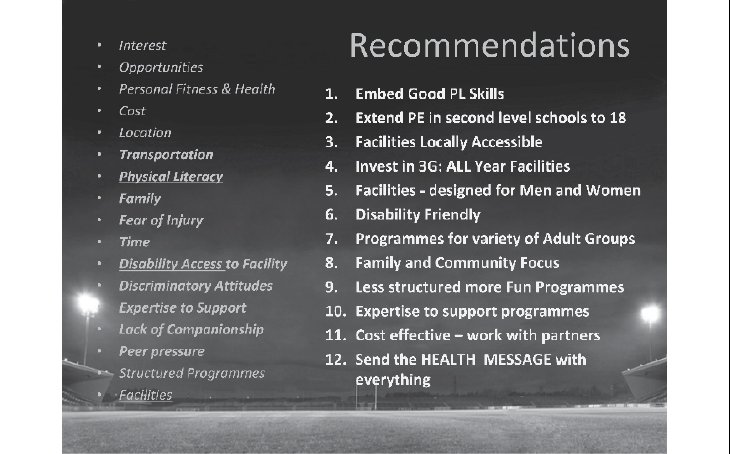

Appendix 4:

Written Submissions to the Committee

Appendix 5:

List of Witnesses who gave Oral Evidence to the Committee

Appendix 6:

List of Research Papers

Appendix 7:

Research Papers

Appendix 8:

List of Additional Information considered by the Committee

Appendix 9:

Additional Information considered by the Committee

Appendix 10:

List of Additional Information from Witnesses

Appendix 11:

Additional Information from Witnesses

List of Abbreviations used in the Report

BIG Big Lottery Fund

BMA British Medical Association

BMFA British Model Flying Association

CHS Continuous Household Survey

DCAL Department for Culture, Arts and Leisure

DOE Department of the Environment

DEL Department for Employment and Learning

DENI Department of Education

DETI Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

DHSSPS Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

DRD Department for Regional Development

DSD Department for Social Development

GAA Gaelic Athletic Association

NICE National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

OFMDFM Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister

RNIB Royal National Institute for Blind People

SNI Sport Northern Ireland

Sport Matters Sport Matters: The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and

Physical Recreation 2009-2019

PE Physical Education

Executive Summary

Purpose of the Report

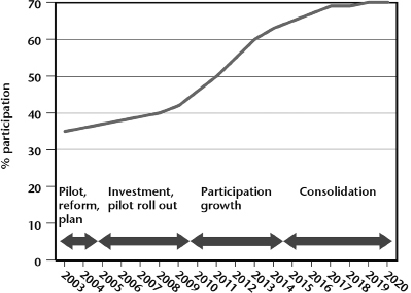

The role of sport and physical activity as an essential part of a healthy lifestyle has been recognised for some time. Recommended levels of participation have been set by the Chief Medical Officer, and in Northern Ireland it is recommended that adults should take 30 minutes of moderate physical activity at least five times a week.

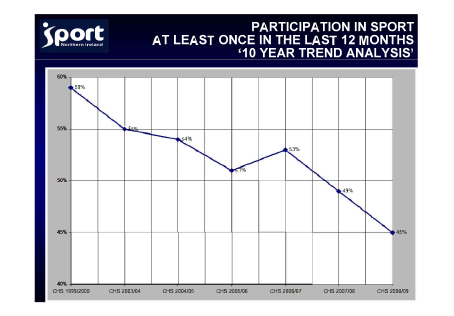

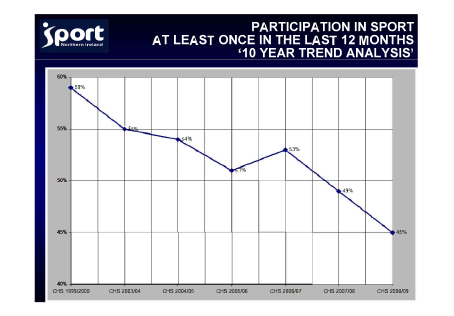

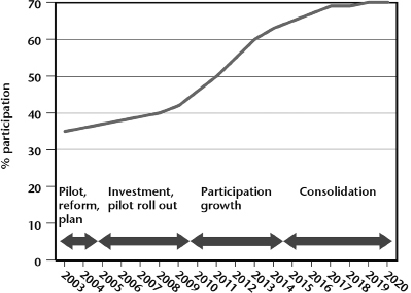

However, statistics show that levels of participation among adults in Northern Ireland have been falling for some time, and as such under the Programme for Government 2008-2011, the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure has a target for halting the decline in adult participation in sport and physical recreation by securing 53% participation.

In this report, the Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure has sought to identify and analyse the barriers to participation, and to consider solutions to increasing participation levels both across the population as a whole and among groups with lower than average participation rates.

Main Findings

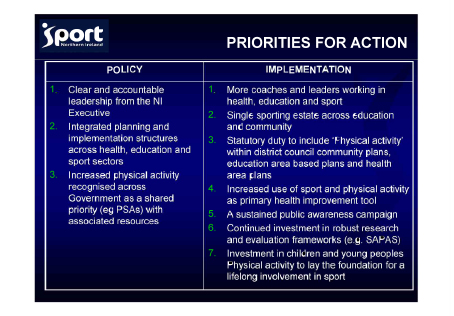

The Committee came to the conclusion that the Executive needs to champion participation in sport and physical activity and ensure that all relevant departments are assigned targets for facilitating participation opportunities under the next Programme for Government. The Committee also recommended that the DHSSPS should invest more of its budget in preventative health measures which involve participation in physical activity.

While the inquiry focused on adults, the Committee recognised that more needs to be done by schools and sports clubs to encourage participation from early childhood until children leave formal education, in order to create the habit for life of participation in sport and physical activity.

In relation to facilities, the Committee came to the view that government departments, local government authorities and sports governing bodies need to maximise the use of land and properties under their control for participation in sport and physical activity.

The Committee recognised that employers have a key role to play in terms of pro-actively encouraging employees to participate in sport and physical activity as part of a wider focus on work/life balance, and that as such DETI should provide advice to employers on such matters.

It is clear that at present the importance of participating in sport and physical activity is not getting through to the majority of the population. Therefore, the Committee is in favour of a government led advertising campaign which contains simple messages as to how people can build either/both organised sporting activity and informal physical activity into their everyday lives.

List of Recommendations

1. We recommend that the Executive prioritises the need to increase participation in sport and physical activity and accordingly provides the necessary funding to implement ‘Sport Matters: The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation, 2009 – 2019’ in the next Comprehensive Spending Review.

2. We recommend to the Executive that the next Programme for Government contains Public Service Agreements for all relevant government departments in relation to actions aimed at increasing participation in sport and physical activity.

3. We recommend that the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) invests more of its budget in preventative health measures which involve participation in physical activity, as a means of reducing obesity related illness and the associated financial cost to the health service over future years.

4. We recommend that the Department of Education is more pro-active in terms of assisting schools to meet the target of providing 2 hours of Physical Education (PE) per week. We recommend that the Department of Education makes it an urgent priority for primary schools to meet this target.

5. We recommend that governing bodies of sport review how they can work more closely with schools to ensure that structures are in place to encourage young people to continue participating in sport and physical activity once they leave formal education.

6. We recommend that sport governing bodies put in place structures to facilitate lifelong participation in sport and physical activity for their members. The Committee points to the good work being done in this area by the GAA as a model of best practice.

7. We recommend that local government authorities conduct an audit of the sport/physical activity facilities currently in their area and develop plans to maximise their use, as well as identifying any gaps in current provision.

8. We recommend that all government departments and their agencies maximise the use of land and properties under their control for participation in sport and physical activity. This includes provision of safe bicycle parking facilities.

9. We recommend that the Department of Education makes school facilities more available to local communities at evenings, weekends and during school holidays.

10. We recommend that the Department for Regional Development (DRD) and local government authorities continue to develop safe walk and cycle paths to encourage more people to take part in informal physical activity and to encourage active travel.

11. We recommend that DRD reduces the speed limits on roads which form part of the National Cycle Network and/or increase signage for motorists in the interests of safety.

12. We recommend that sport governing bodies maximise the facilities under their control to encourage complementary physical activity participation opportunities. For example, the Committee welcomes the creation of flood-lit walkways around sports pitches which provide a safe walking environment.

13. We recommend that local government authorities review changing facilities provision at leisure centres with a view to accommodating both single sex and family changing areas.

14. We recommend that Sport NI sets targets for sport governing bodies to increase their participation rates as part of grant funding packages.

15. We recommend that Sport NI continues to work with other partners to promote programmes which combine physical activity with healthy eating.

16. We recommend that the Executive provides funding on an ongoing basis for advertising campaigns to promote the health benefits of participation in sport and physical activity. Such campaigns should be targeted at the population as a whole and focus on simple messages as to how people can build either/both organised sporting activity and informal physical activity into their everyday lives.

17. We recommend that public and private sector employers pro-actively encourage employees to participate in sport and physical activity as part of a wider focus on work/life balance.

18. We recommend that the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI), provides advice to employers as to how they can collaborate with sport/leisure service providers regarding the provision of participation opportunities for employees.

19. We recommend that DETI provides advice to employers as to how they can facilitate more active travel to work, for example through the provision of bicycle storage and changing facilities.

20. We recommend that Sport NI, local authorities, other public sector funders and sports governing bodies fund programmes which provide opportunities for families to participate as a unit in sport and physical activity.

21. We recommend the expansion of specific programmes aimed at increasing participation among women, people with disabilities, older people, people from low income groups, and people from ethnic minorities.

22. We recommend that local government authorities explore ways of encouraging more people with childcare responsibilities to use their leisure facilities.

23. We recommend that local government authorities explore ways of encouraging more people on lower incomes to use their leisure facilities.

24. We recommend that local authorities enhance training for staff at leisure centres on how to best provide services for women, people with disabilities, older people, people from low income groups, and people from ethnic minorities.

Introduction

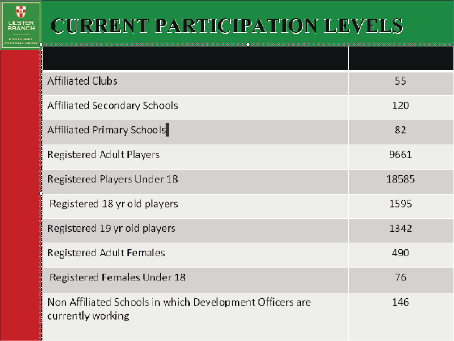

Inquiry Terms of Reference

1. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure agreed to conduct an inquiry into participation in sport and physical activity in Northern Ireland on 10 December 2009. The terms of reference for the inquiry were agreed at the Committee meeting on 7 January 2010.

Terms of Reference for the Inquiry

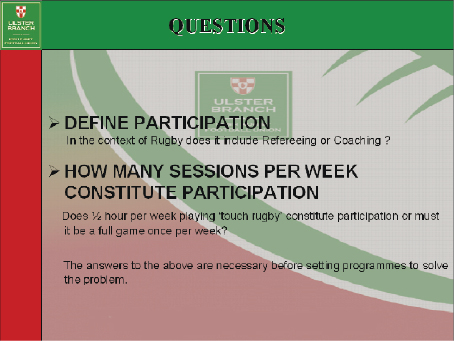

2. The Committee sought to identify, analyse and consider solutions to the ongoing decline in adult participation in sport and physical activity as evidenced in the NI Continuous Household Survey.

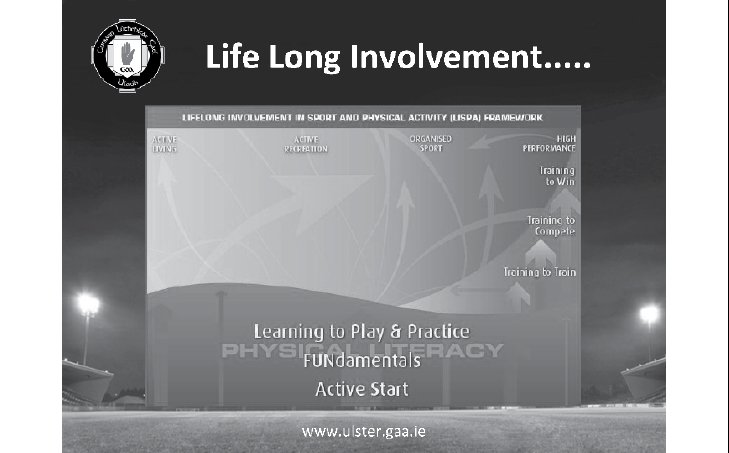

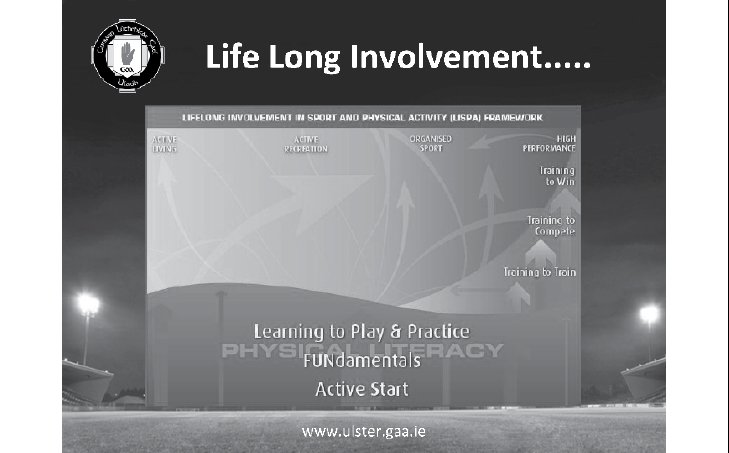

3. Under the Programme for Government 2008-2011, the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure has a target for halting the decline in adult participation in sport and physical activity by securing 53% participation. The Committee is concerned that all steps are taken as necessary to meet that target.

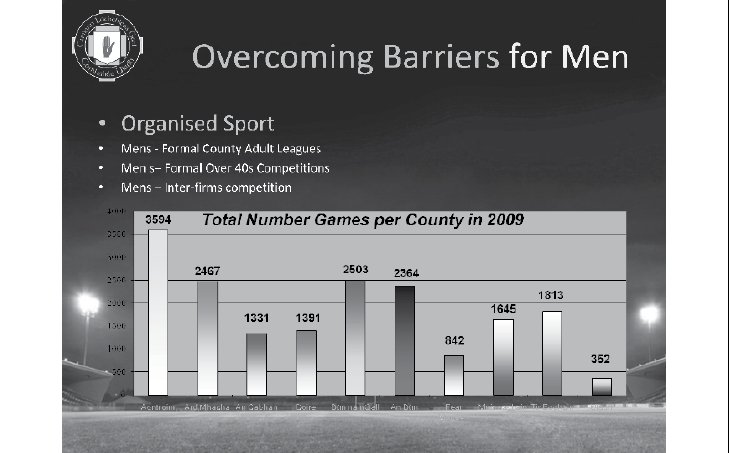

4. Within that framework the Committee sought to:

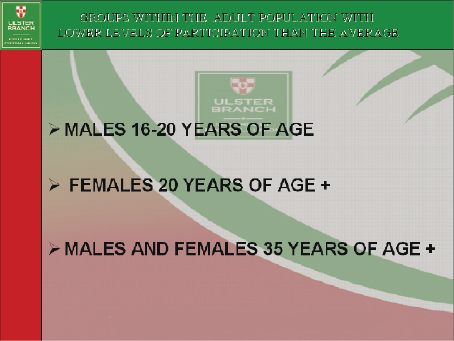

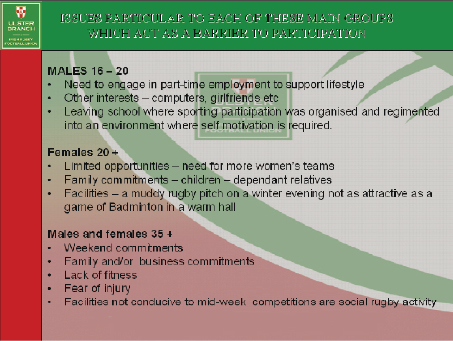

- Identify the main groups within the adult population which have lower levels of participation than the average rate for adults;

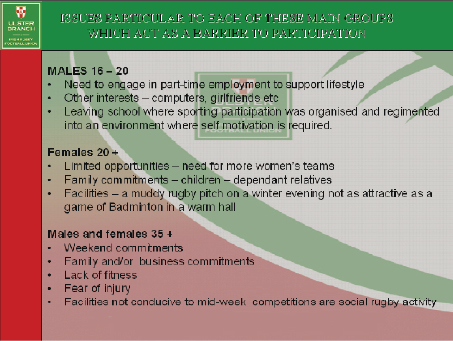

- Identify and analyse the issues particular to each of these main groups which act as a barrier to participation;

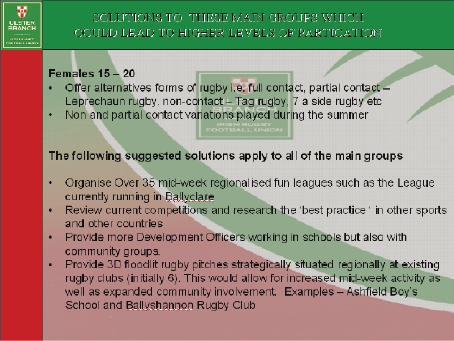

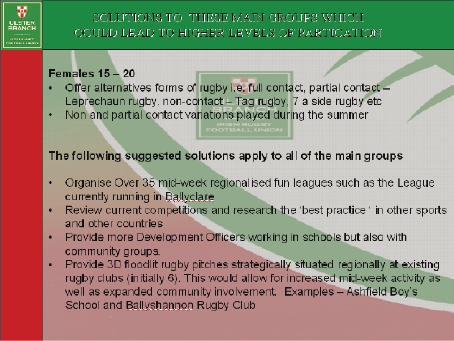

- Consider solutions particular to each of these main groups which could lead to higher levels of participation, including considering examples of best practice from other countries and regions;

- Report to the Assembly; making recommendations to the Department and/or others.

The Inquiry Process

5. The Committee made the decision to hold an inquiry into participation in sport and physical activity in Northern Ireland in December 2009. Advertisements requesting submissions by 12 February 2010 were placed in the local newspapers. In addition, the Committee agreed to write to 122 individuals and interest groups, to request submissions on each of the matters included within the terms of reference. A list of those individuals and groups that submitted evidence is attached at Appendix 3.

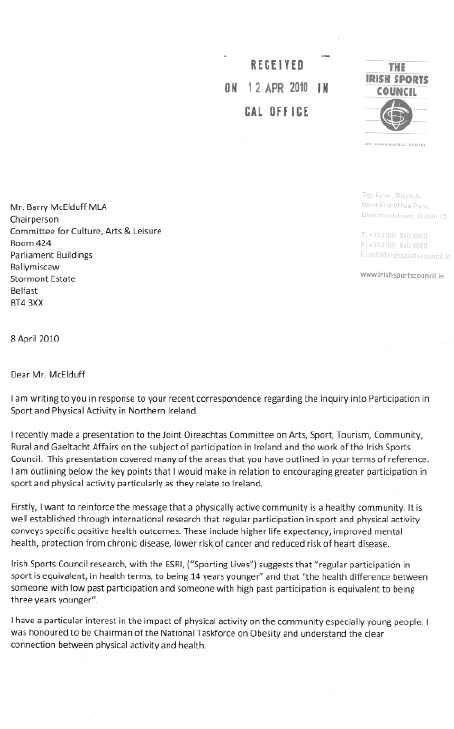

6. The Committee received 36 submissions and considered oral evidence from 10 key stakeholders, including the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. A list of witnesses who provided oral evidence to the Committee is attached at Appendix 5. Transcripts of the oral evidence sessions are attached at Appendix 2.

7. The Committee received additional information to further inform the inquiry. A list of the additional information considered by the Committee can be found at Appendix 8. Copies of these additional papers are included at Appendix 9.

8. The Committee also commissioned 6 research papers on participation in sport and physical activity.

- The first paper entitled ‘Background information into participation in sport and physical activity’ provides an overview of the main issues in relation to the inquiry.

- The second paper entitled ‘Barriers to sports and physical activity participation’ examine a range of barriers and how they affect specific socio-cultural and socio-economic groups.

- The third paper supplements the paper ‘Barriers to sports and physical activity participation’ and provides further information on education as a determinant of activity levels among adults.

- The fourth paper entitled ‘EU perspectives on sport and physical activity’, provides an insight into sport and physical activity promotion throughout the EU, with a particular focus on Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK.

- The fifth paper entitled ‘GP exercise referral schemes’ analyses the strengths and weakness in the referral of patients by GPs to voucher-based exercise schemes.

- The sixth paper is a submission matrix which analyses all written submissions received in relation to the inquiry.

9. Copies of these papers are included in Appendix 7.

10. During the month of March 2010 Assembly Research Services personnel met with 5 school groups who were on routine visits to the Northern Ireland Assembly. A discussion was facilitated on what both motivates and acts as obstacles to young adults participating in sport and physical activity. A series of questions were put to each of the 5 groups and a report on the findings is at Appendix 9.

11. On 23 March 2010, the Chairperson and secretariat staff participated in an audio conferencing session at Stormont Castle with a Finnish government official from the Ministry of Education. The discussion centred around the strategies adopted by the government in Finland to successfully increase participation in sport and physical activity in their country. A report of the discussion is at Appendix 9.

12. On 25 March 2010 Assembly Research Services hosted a stakeholder conference in the Long Gallery, Parliament Buildings on behalf of the Committee. Twenty-seven delegates from 17 organisations attended, along with Members of the Committee and various topics in relation to the inquiry were discussed across 5 different focus groups. A report on the findings of the conference is at Appendix 9.

13. The Committee considered its draft recommendations on 20 May, 27 May and 3 June. The draft report was considered on 17 June, 24 June and on 1 July 2010 the Committee agreed its final report and ordered that the report be printed.

Acknowledgements

14. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure would like to express and record its appreciation and thanks to all the organisations and individuals who contributed to the inquiry.

Chapter 1 — Current levels of participation

Recommended levels of physical activity

15. The role of sport and physical activity as an essential part of a healthy lifestyle has been recognised for some time. Recommended levels of participation have been set by the Chief Medical Officer, and in Northern Ireland it is recommended that adults should take 30 minutes of moderate physical activity at least five times a week.

16. There are many benefits at both an individual and community level from participating in sport and physical activity. These include enhanced physical and mental well-being, improved productivity at the workplace, social and community cohesion, enhanced educational achievement and positive environmental impacts.

17. In addition sport makes a significant contribution to the economy. Figures from 2006/2007 show that in Northern Ireland spending on sport contributed £452 million per annum to the economy or 2% of GDP. The Northern Ireland Tourist Board estimates that activity tourism contributes £30 million a year to the local economy, and there are approximately 13,700 people employed in sport and physical recreation activities in Northern Ireland.

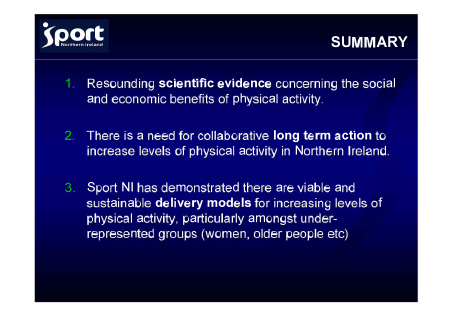

18. In terms of the health benefits which result from participating in sport and physical activity, these are particularly strong. When Sport NI presented oral evidence to the Committee it quoted the Chief Medical Officer speaking in 2005:

The scientific evidence is compelling. Physical activity not only contributes to well-being, but is also essential for good health . . . There are few public health initiatives that have greater potential for improving health and well-being than increasing activity levels.

19. The British Medical Association NI (BMA(NI)) made a similar point when it addressed the Committee:

The British Medical Association has a long-term interest in the health of the public and believes that the most effective way to improve the population’s health is to improve activity levels among inactive people.

The costs of physical inactivity

20. When it is accepted that participating in sport and physical activity is essential in terms of health, it follows that the consequences of low levels of participation are serious.

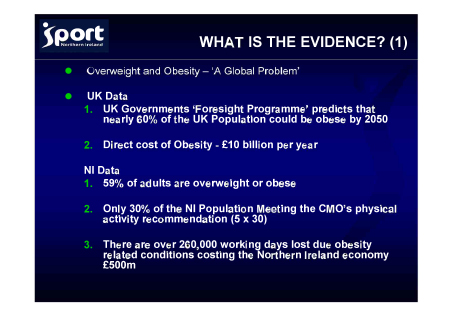

21. Both Sport NI and BMA (NI) referred the Committee to a report by the Northern Ireland Audit Office in 2009 stating that around 2,000 deaths a year in Northern Ireland can be attributed to physical inactivity.

22. BMA (NI) elaborate further on the health-related dangers of physical inactivity:

However, the evidence demonstrates that an inactive lifestyle has a substantial negative impact on both individual and public health and is the primary contributor to a broad range of chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes and some cancers. The high level of individual suffering caused by those diseases, together with the substantial associated financial costs, makes this a major public health issue.

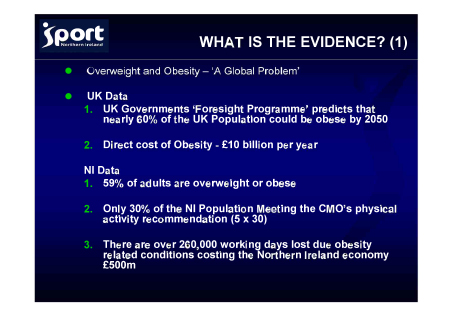

23. The cost of physical inactivity is not only in terms of people’s health, but it also has an economic dimension. It is recognised that physical inactivity is a fundamental cause of obesity and obesity is expensive. Both Sport NI and Belfast Healthy Cities made the point that obesity levels in the UK have doubled in the last 25 years, and in Northern Ireland 59% of adults are either overweight or obese. BMA (NI) provided some stark statistics:

Obesity is estimated to be causing around 450 deaths each year in Northern Ireland with a cost of around £500 million to the economy (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (2002), “Investing for Health”, Belfast, DHSSPS).

It also places additional demands on the health and personal social services. Tackling obesity could save the health service in Northern Ireland £8.4 million, reduce sickness absence by 170,000 days and add an extra ten years of life onto an individual’s life span (Source: DHSSPS Economics Branch (2003), “Unhealthy Living Model 2nd Edition”, Belfast, DHSSPS).

Statistics on current levels of participation in sport and physical activity in NI

24. There are a number of indicators relating to adult participation in sport and physical activity in Northern Ireland.

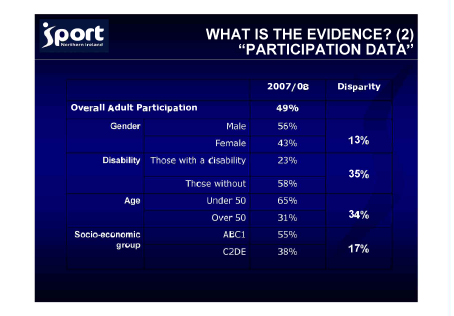

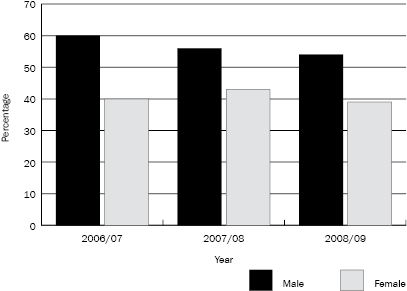

25. Sport NI advised the Committee that the data from the Continuous Household Survey (CHS) revealed that in 2008-2009 only 45% of the adult population had participated in sport once a year. In 2007-2008 the figure was 49% and in 1999-2000 it was 59%. This demonstrates that activity levels have been declining.

26. The figures on the number of people in Northern Ireland meeting the Chief Medical Officer’s recommendations on physical activity levels are also low. Only 30% of adults are meeting the target. As BMA (NI) put it:

In terms of physical activity, the Northern Ireland health and social well-being survey found that only 30% of adults in Northern Ireland meet the 150-minute criterion. Therefore, 70% of people are still inactive or do not take enough exercise to be beneficial to their health.

European context

27. The statistics for Northern Ireland are part of a wider European trend. A recent survey revealed that one in four Europeans are almost totally inactive. It was found that 40% of EU citizens play sport at least once a week and 65% engage in some form of physical activity, while 25% of the respondents declared themselves to be almost completely inactive.

28. However, the figures do fluctuate considerably between the various parts of the EU, with the percentage of people taking regular exercise varying from 72% in Finland to 3% in Greece. Finland (72%), Sweden (72%) and Denmark (64%) all outstrip the EU average of 40% for people exercising once a week or more.

Sport NI research on participation levels

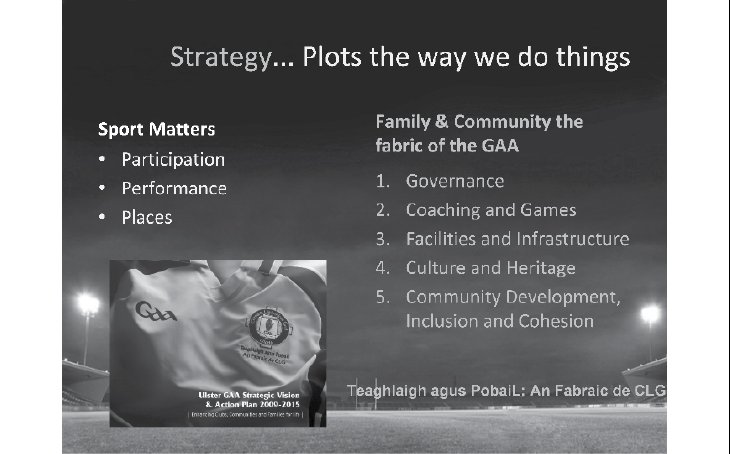

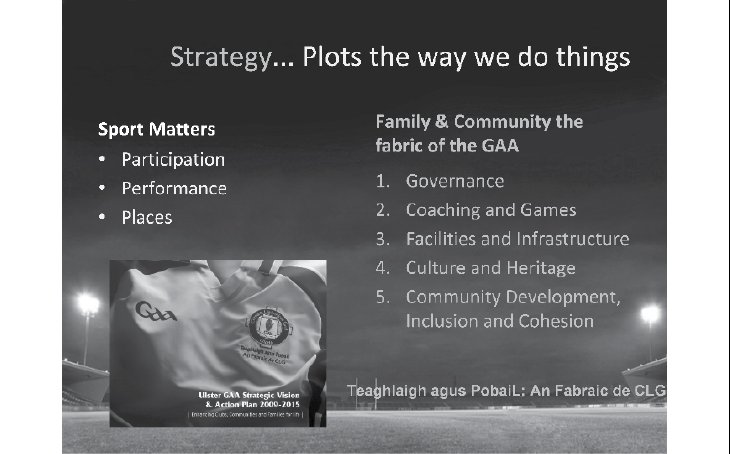

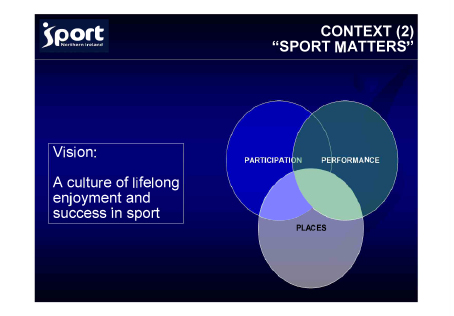

29. “Sport Matters – The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation 2009-2019” was launched by DCAL in May 2010. It focuses heavily on the need to halt the decline and then increase participation levels among adults. Sport Matters contains 26 high level targets across the themes of participation, performance and places. Fourteen of these targets relate to participation.

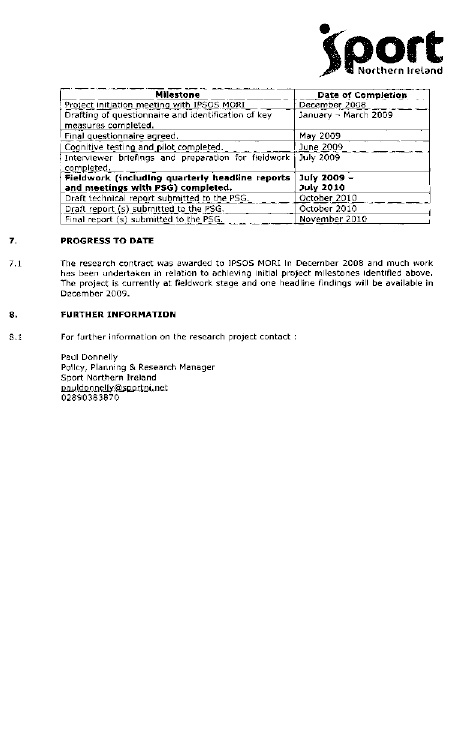

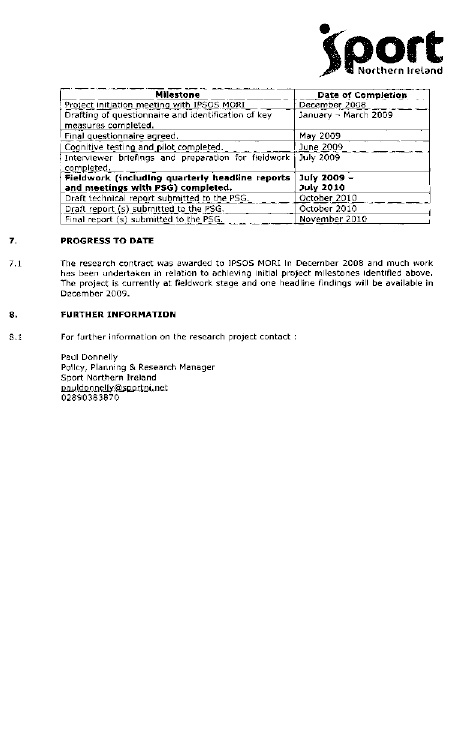

30. In addition Sport NI is currently carrying out research into adult sport and physical activity in Northern Ireland and the final report is expected in late 2010.

31. During its oral evidence to the inquiry Sport NI provided a broad overview of the sport and physical activity survey known as SAPAS:

The survey is the largest that has been commissioned since 1994. It will provide statistically robust data on participation rates, information on club membership, volunteering and coaching in sport, as well as information on many other lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and fruit and vegetable consumption.

We developed a new research instrument because we felt that the CHS did not provide the data that we needed to formulate and implement policy. The sport and physical activity survey (SAPAS) will provide us and this Committee in particular with the information that is needed to get the full picture of what happens with sport.

32. The Committee welcomes the survey and looks forward to the publication of its findings. It is anticipated that the information gathered in the context of the Committee’s inquiry will serve to complement the research being carried out by Sport NI.

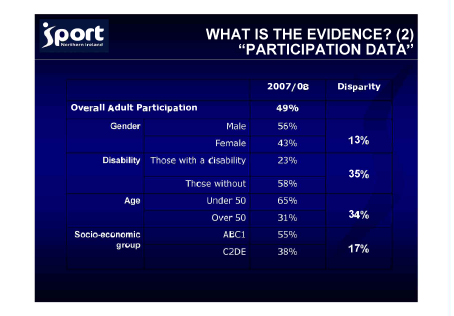

Chapter 2 — Groups which have lower levels of participation within the adult population

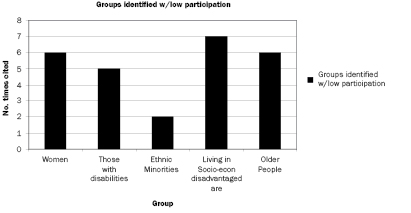

33. While it is clear that the adult population as a whole needs to increase the amount of exercise it takes, there are particular groups within the population which experience even lower than average participation rates. The Committee recognised that there needs to be a two-pronged approach – that is increasing participation rates both across the population as a whole and among specific groups with a history of low levels of participation.

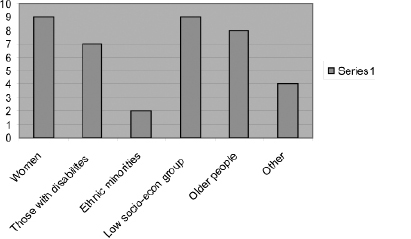

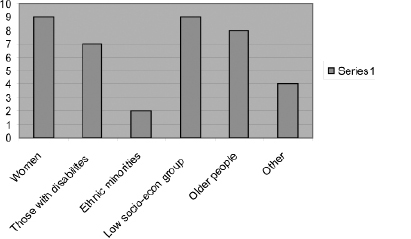

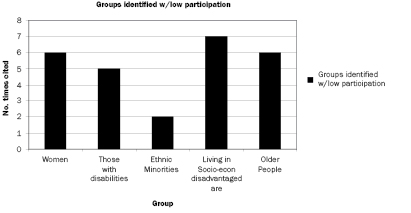

34. At the outset of the inquiry, the Committee commissioned a paper from Assembly Research Services to identify the groups which have lower levels of participation within the adult population. The research paper identified the following groups:

- Women

- People with disabilities

- People from areas of social disadvantage

- Older people

- People from black and minority ethnic communities

- Members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans community.

35. This ties in with the information contained in DCAL’s Sport Matters: The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation 2009-2019. It identifies women, people with disabilities, people from areas of social disadvantage, and older people as having lower levels of participation, and includes specific targets for increasing their participation rates by 2019.

36. A similar picture emerged from the evidence gathered at the Committee’s stakeholder focus group conference. Participants identified a number of under-represented groups - older people, people with disabilities, women, people from disadvantaged areas, and people from black and ethnic minority communities.

Women

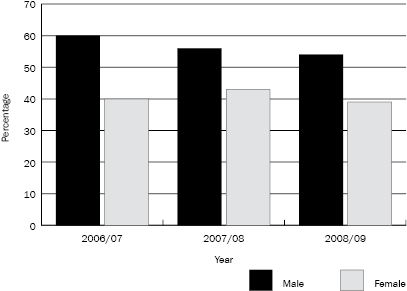

37. Sport Matters states that the evidence shows that female adult participation rates are lower than those for males. The Continuous Household Survey 2005/2006 revealed that only 25% of females had participated in the previous week compared to 36% of males – a gap of 11%.

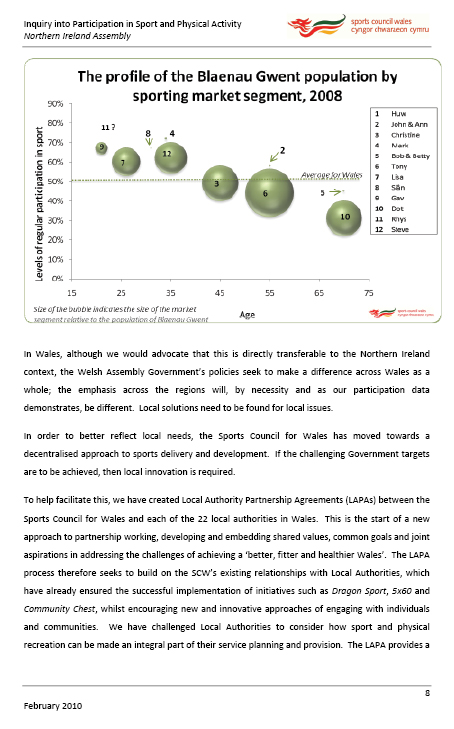

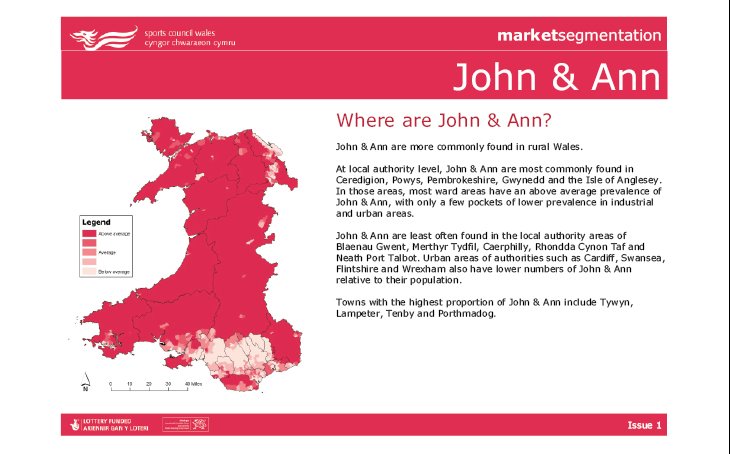

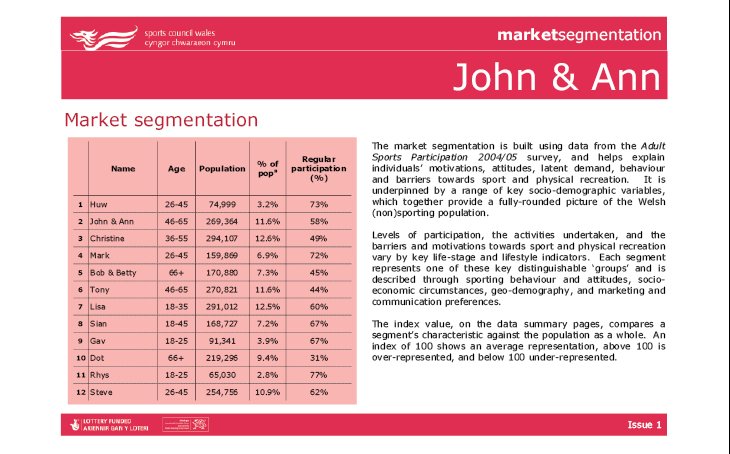

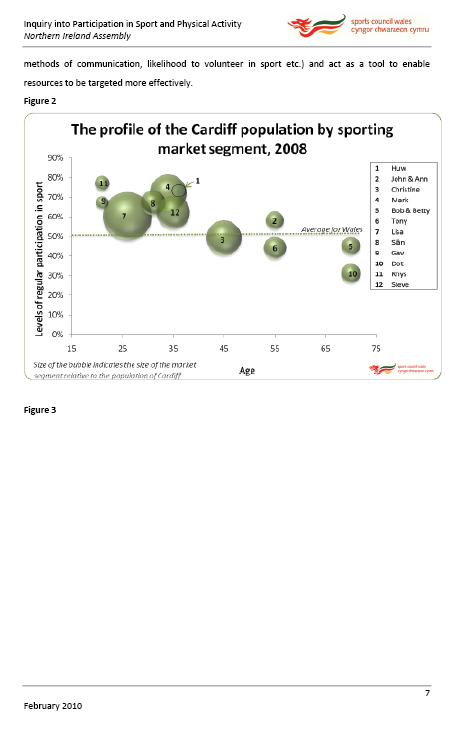

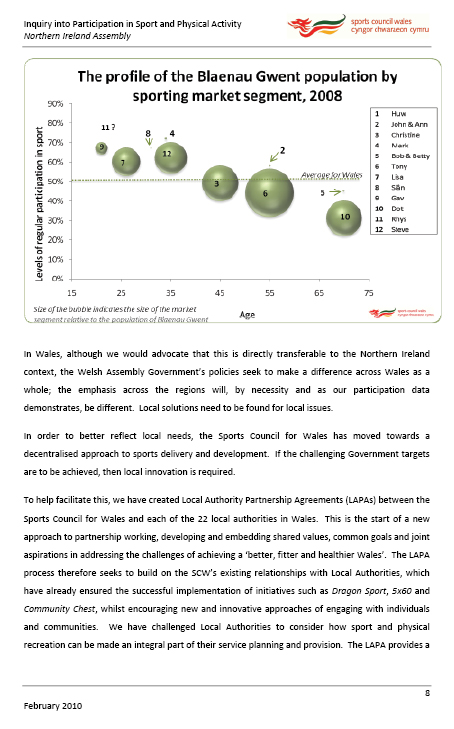

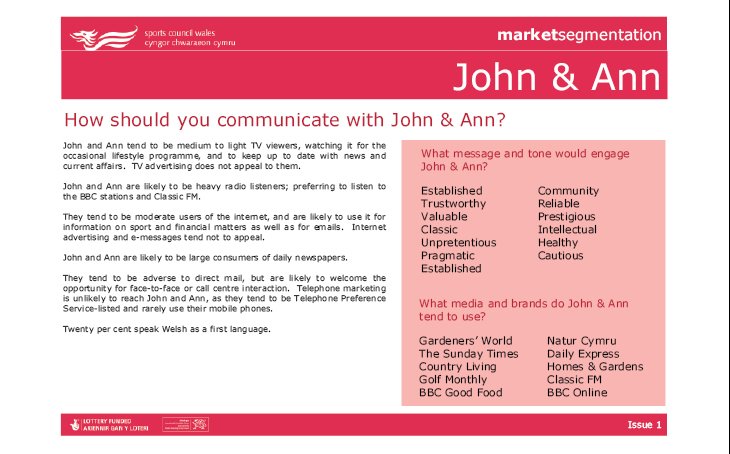

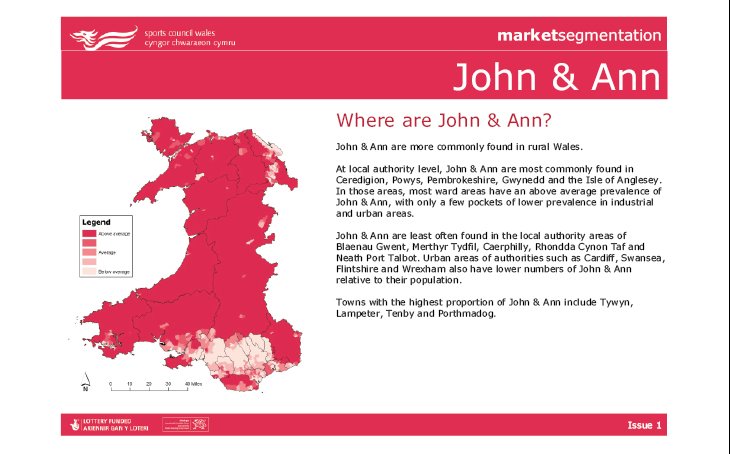

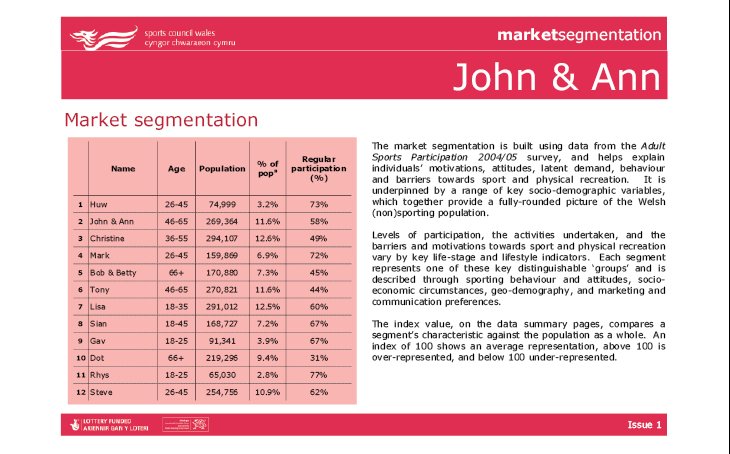

38. This pattern is evident in other countries and regions. The Sports Council for Wales told the inquiry:

There are also disparities in levels of participation by gender group: 54% of adult men in Wales regularly participate in sport and physical recreation; this compares to 47% of adult women.

39. Similarly, Sport Scotland reported that in Scotland males are more likely to participate than females (76% versus 70%). Again, information from the Republic of Ireland told a similar story. The Irish Sports Council advised:

In 2005, the Women in Sport initiative was established to address the clear gender gap in sports participation with only 34% women participating regularly compared to 52% of men.

40. The Public Health Agency also referred to women having lower levels of participation, in particular young mothers:

In addition to the general population figures mentioned above, research addressing the specific groups of women and young people has demonstrated that 72% of women in Northern Ireland do not participate in enough physical activity, with young mothers having the lowest levels of physical activity (former Health Promotion Agency, 2008, Armstrong, Bauman & Davies, 2000).

41. Sport NI also pointed to new mothers as a group prone to lower participation levels, stating:

It is recognised that there is a drop in participation in sports after children are born.

People with disabilities

42. Sport Matters states that recent data indicates that participation rates for people with a disability are around half that for the adult population as a whole. It refers to the Continuous Household Survey 2005/2006 which revealed that only 13% of people with a disability had participated in the previous week compared to 29% for the adult population as a whole.

People from areas of social disadvantage

43. Sport Matters states that recent data indicates that people from socio-economically disadvantaged groups have lower levels of participation. The Continuous Household Survey 2005/2006 revealed that only 20% of people from socio-economic groups D and E had participated in the previous week compared to 29% for the adult population as a whole.

44. Evidence from the Irish Sports Council suggests that income can play a significant role in terms of influencing whether a person participates in sport and physical activity. A report in 2008 indicated a 2% drop in active participation in sport among adults in the Republic of Ireland. The Irish Sports Council states:

The evidence very strongly suggests that the recession was behind the drop in active participation. The decline was concentrated among lower income households. The sharpest fall also coincided with the steep drop in consumer spending that occurred in early 2008. And the hardest hit activities were individual sports such as golf and exercise activities (e.g. using the gym), which tend to be more expensive.

45. Similarly, Sport Scotland advised that in Scotland participation increases as deprivation decreases, with 80% participation in the least deprived areas compared to 63% in the most deprived areas in 2008.

46. The Sports Council for Wales backed up this finding:

There is also a clear relationship between participation and social class. The highest levels of participation are seen in socio-economic group (SEG) AB and the lowest in SEG E.

Older people

47. Sport Matters states that recent data indicates that participation rates for older people (aged 50 or over) have lower levels of participation. The Continuous Household Survey 2005/2006 revealed that only 18% of older people had participated in the previous week compared to 29% for the adult population as a whole.

48. A similar situation exists in Wales as reported by the Sports Council for Wales:

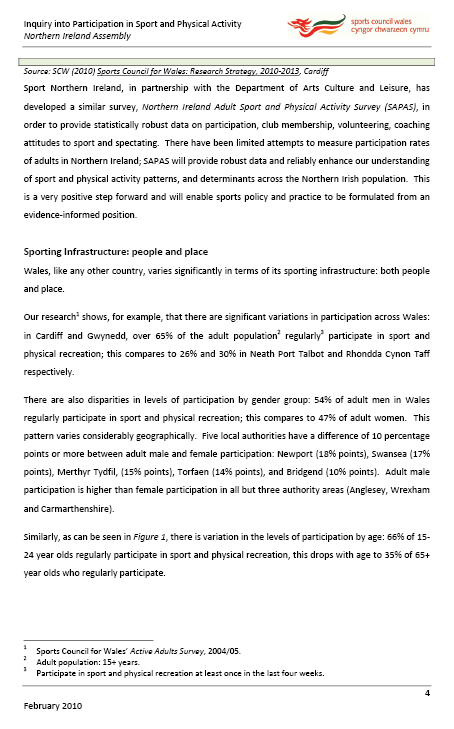

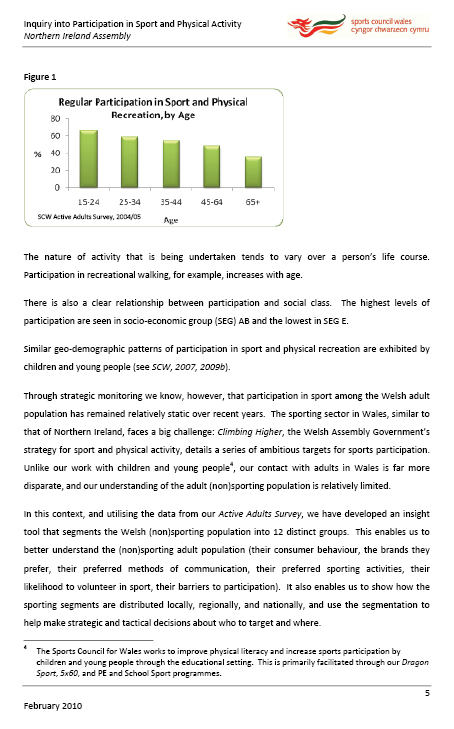

. . . there is variation in the levels of participation by age: 66% of 15-24 year olds regularly participate in sport and physical recreation, this drops with age to 35% of 65+ year olds who regularly participate.

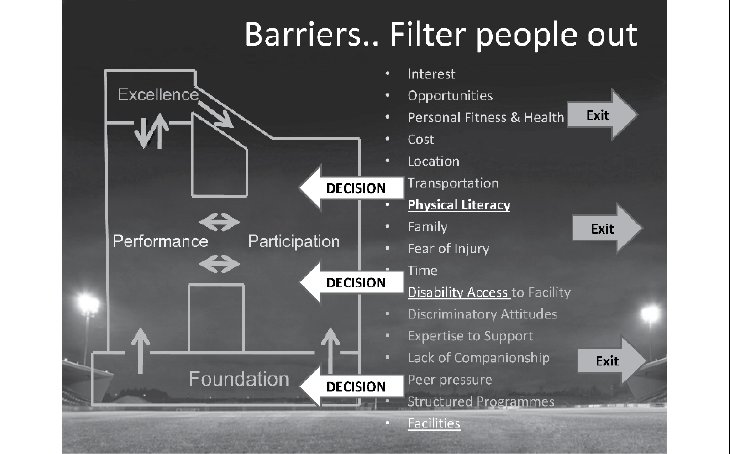

Chapter 3 — Barriers to participation

49. The Committee recognised that there are both general barriers to participation which affect the adult population as a whole, and the barriers specific to each of the groups identified in Chapter 2.

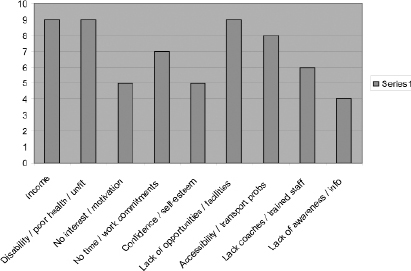

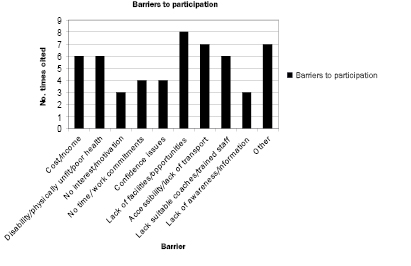

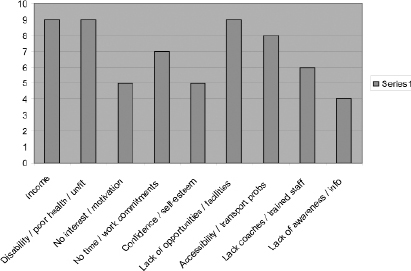

General barriers

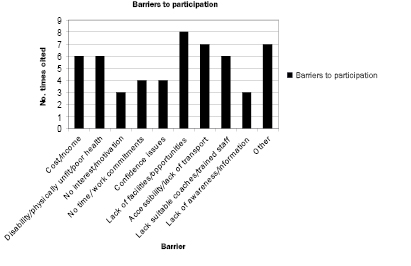

50. The inquiry identified a range of general barriers which can prove an obstacle to people participating in sport and physical activity. They key barriers are explored below.

Knowledge barriers - what is physical activity and what levels are required?

51. A lack of knowledge in relation to the required levels of physical activity for health benefits, as well as suitable types of activity can act as a barrier to more people taking exercise.

52. Sport NI advised the Committee that the vast majority of adults do not know what the recommended levels of physical activity as set down by the Chief Medical Officer are:

We carried out a survey of public attitudes to sport and physical activity in 2008. Only 7% of the adults who were surveyed indicated that they were aware of and understood the recommendations on physical activity. That tells us straightaway that there is work to be done.

53. Similarly, research conducted by Assembly Research Services with local school groups revealed that respondents from only two out of the five groups had an awareness of the “30 minutes a day five days a week message.”

54. As well as there being a lack of knowledge about the appropriate levels of physical activity, there can be inadequate understanding of what constitutes physical activity. For example, the research conducted with local school groups asked participants to describe their impressions of an ‘active person’. Across all the groups the term ‘active’ was linked to ‘sporty’. Terms linking ‘active’ to non-competitive physical activity, in other words not sport, were cited less frequently.

55. This ties in with the evidence obtained from the stakeholder focus groups conference held as part of the inquiry. Delegates stated that the terms ‘sport’ and ‘physical activity’ were not sufficiently defined and thus acted as a barrier. The view was put forward that a broad definition of physical activity, including home, leisure, work and travel based activities was required.

56. A lack of self-confidence was also identified as a barrier to participation. Delegates at the stakeholder focus groups event made the point that many people hold negative self-beliefs such as ‘I am not fit/thin/young enough’ to take part in sport or physical activity.

57. Inhibiting ideas about what constitutes physical activity and what sorts of people can take part in it, can sometimes stem from negative experiences of PE at school.

58. The research obtained from the stakeholder focus group event revealed that too much emphasis on competitive sport at school can lead to people having a negative perception of exercise in general. This point was also made in written evidence by a fitness trainer in describing his typical client:

In my findings this type of client has no sporting background and PE at school consisted of a specific sport which held no interest for them. Being forced into doing it put them off any kind of sport.

59. An Assembly research paper commissioned for the inquiry suggested that PE in the school environment is very much centred on competitive sports. A study carried out in 2002 on physical education systems within the EU noted a number of factors which have had a negative affect on physical education provision and pupil experiences of PE. These factors include the PE curricula being almost exclusively focussed on competitive sports.

Cultural barriers - sedentary nature of modern life

60. The evidence gathered during the inquiry pointed to the fact that the culture of modern life itself could act as a barrier to participation.

61. Many adults spend the majority of their days at the workplace which in some instances can discourage physical activity. The British Medical Association NI (BMA (NI)) explained that many jobs involve long periods of sitting and physical inactivity:

However, nowadays, the seats that we are sitting on are possibly the most dangerous items, because they lead to complacency as we sit in our offices gazing at computer screens. That has a cumulative effect and increases the number of hours that we spend doing nothing other than moving our mouse hand.

62. BMA (NI) also argued that even the type of clothing employees are expected to wear in the workplace mitigates against active travel to and from the work place, a form of physical activity which is recognised as being an integral part of increasing participation levels:

I was struck, reading some of the papers, to find that dress code at work is an issue. To dress as we are today, very elegantly and neatly, does not lend itself to cycling or jogging into work.

63. Sport NI put forward a similar view:

Some of the reasons offered for that decline are evidence based and relate to the sedentary nature of many jobs, the increased use of the car and less reliance on active travel . . .

64. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group conference also flagged up these cultural barriers to greater participation:

Delegates argued that modern lifestyles, which value convenience and productivity, made it easier to be sedentary. It was noted that working practices, in which individuals are desk bound, work long hours and often work through their lunch, were counter-productive to active lifestyles.

Practical barriers - lack of appropriate facilities and ability to travel to them

65. The evidence obtained from the stakeholder focus group event suggested that the practical issues of access to and cost of facilities could be barriers to participation across society. For example, not all local leisure centres offer a swimming pool thus negating swimming as an option for those who would favour this form of exercise. Participants also noted that there was a lack of well lit, green spaces suitable for walking, particular in the evenings. This issue was also raised by BMA (NI) who referred to a lack of playgrounds and parks close to where people live.

66. The cost of accessing facilities and classes was also raised by delegates at the stakeholder focus group event, as was the availability and cost of public transport. This is particularly problematic in rural areas. This point was also made by the Women’s Centre Regional Partnership (WCRP) and the Countryside Access & Activities Network.

Barriers for groups with lower levels of participation

Women

67. The inquiry identified a range of barriers which can prevent women from participating in sport and physical activity.

68. One of the key issues is the availability of suitable childcare. The WCRP stated:

In the research that was carried out before the project began, and through the work that women’s organisations do in general, lack of childcare was identified as being the biggest barrier that women face.

69. Sport NI made a similar point:

It is recognised that there is a drop in participation in sports after children are born. Whenever a busy lifestyle becomes hectic, people have less time for themselves. They also face the additional problems of getting childcare and crèche facilities and finding the personal space to get out and be active.

70. The WCRP argued that women face additional caring responsibilities, not limited to childcare, which can impede on the time available for exercise:

However, childcare is only one aspect of the caring responsibilities that women in Northern Ireland have, and those caring responsibilities can last a lifetime. When women are young, they may care for their siblings; when they are mothers, they care for their children; and, even in later life, women may care for their elderly parents, a member of their family who is sick or their grandchildren.

71. This point is linked to the issue of women not prioritising themselves and being reluctant to devote time and money to their own well-being. The Public Health Agency in their written submission cited research showing that young mothers are almost twice as likely as men to experience time pressures as a result of the demands of young children, indeed this may be one of the main barriers to getting young mothers physically active. A lack of time and the demands of parenting can all be barriers for women.

72. This theme was also identified in research commissioned by the Committee which stated one study had found that 66% of women in the UK experience time pressures, and that these pressures are most acute among working mothers.

73. Similarly, the WCRP stated:

However, being a woman in a disadvantaged community creates an added economic disadvantage. Those women belong to households with very limited disposable income and, because many women are not the earner of what little income is brought into the household, there is reluctance on their part to spend that income on themselves. Women prioritise the needs of the family.

74. The GAA also referred to the tendency for women to prioritise the needs of the family:

Time is an issue, particularly for women whose focus moves once they get married and start to have families; they start to shy away from and then exit sport.

75. A further barrier identified by research commissioned by the Committee is the perception that sport and physical activity are unfeminine. One of the contributing factors is the media’s portrayal and coverage of women’s sport. One study revealed that in 2006 newspaper coverage of women’s sport accounted for only 5% of total sporting coverage. It has been argued that this attitude has marginalised women’s sport and instilled negative perceptions of sport and physical activity among women, particularly in their formative years. Alongside this issue is the fact that there is a lack of positive, physically active female role models.

People with a disability

76. A lack of accessible facilities can act as a barrier to participation among people with a disability. Access can take two forms – the physical design and layout of the facility, and the ability of staff to be able to facilitate the needs of disabled persons.

77. In its evidence to the Committee, the GAA referred to the issue of physical access:

Disability access is another concern. Although Sport NI emphasises the need to make facilities accessible for people with disabilities, constant improvement is required, particularly with respect to changing rooms.

78. Similarly, the research commissioned by the Committee stated that the built environment and the design of equipment can act as a barrier to participation. Furthermore, facilities often lack dedicated staff members to assist with access issues.

79. The RNIB and the Countryside Access & Activities Network both identified a lack of awareness on the part of service providers as to the needs of disabled people. In addition, cost can be another barrier when the disabled person requires a companion to undertake the activity with them, and the companion is required to pay an entrance fee. The availability of suitable public transport for those with a disability was also mentioned.

80. Craigavon Borough Council also made the point that a lack of competitive sporting opportunities could act as a barrier to people with a disability.

Older people

81. Older people can face a range of barriers in terms of participation. Craigavon Borough Council made the point that there may be lack of suitable activities available for older people provided by coaches who understand older people’s particular health concerns. Older people can also lack the self-confidence to take part in sport or physical activity.

82. The Older People’s Advocate advised that transport can also be an issue, because not all older people drive:

Another area where we would find older people would struggle to use the facilities available to them would be in relation to transport - many forms of community transport focus on providing access to facilities for those with disabilities but there are many older people particularly women who do not drive and therefore find it difficult to get themselves from their homes to the leisure facilities especially in rural areas.

83. The Older People’s Advocate also made the point that older people these days can often have caring responsibilities which impact on their ability to take part in physical activity:

Some find when using the facilities for older people the crèche is closed meaning any grandparents with caring responsibilities cannot use the facilities available to them.

84. Another barrier of a practical nature is the financial cost of participating in activities. This particularly affects older people as research shows that 17% of older people live in low income households.

85. As is the case with women, a lack of role models in the media can deter older people from participating. Linked to that is the self-perception by some older people who consider themselves as being ‘past it’ and the cultural notion that during retirement people should ‘put their feet up’ and become less active. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group made a similar point suggesting that older people were largely under the impression that they should ‘sit back and take it easy’.

People from areas of social disadvantage

86. Taking part in sport and physical activity can involve financial costs in terms of club membership, equipment, entrance fees to leisure centres, transport costs, and childcare costs. For people on lower incomes these costs can prove an obstacle to participation.

87. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group event suggested that there may also be a psychological barrier for people from areas of social disadvantage, including a lack of self confidence and motivation.

88. A lack of safety was also raised by delegates as a barrier, specifically in areas of social disadvantage where well lit, green spaces are often not available. This point was also made in a research paper commissioned by the Committee which stated that in areas of high crime people might be disinclined from jogging or walking.

89. The correlation between educational achievement and rate of participation in physical activity is also a relevant factor. Those with lower levels of education may have had under exposure to health messages and are therefore inclined to participate less.

People from minority ethnic groups

90. For people from ethnic minorities language and culture can act as barriers to participation. The issue of language was mentioned by the Countryside Access & Activities Network and the Irish Football Association (IFA).

91. In its oral evidence, the GAA explained some of the difficulties and how they were working to overcome them:

Engagement with foreign nationals is another barrier to overcome for adult active recreation. The gentleman pictured in our submission to the Committee is called Abdul, and he is from Nigeria. He has been playing Gaelic games for about eight years and has also started to referee. Tooling up GAA clubs to cope with language barriers and people of differing cultures and customs is a challenge that we are trying to address through our ongoing education programme.

92. Language can also be an issue in relation to promotional material advertising opportunities for sport and physical activity. Literature may not be translated or provided directly to ethnic minority community groups.

93. Craigavon Borough Council identified the fact that people from ethnic minorities may have different work patterns and may wish to take part in physical activity at ‘non-traditional times’ such as late evenings and Sundays when local facilities may be shut.

94. As with all the other groups mentioned above, a lack of role models can also prove a deterrent to participation. The existence of racism in sport, both institutional and at an individual level can also act as a barrier.

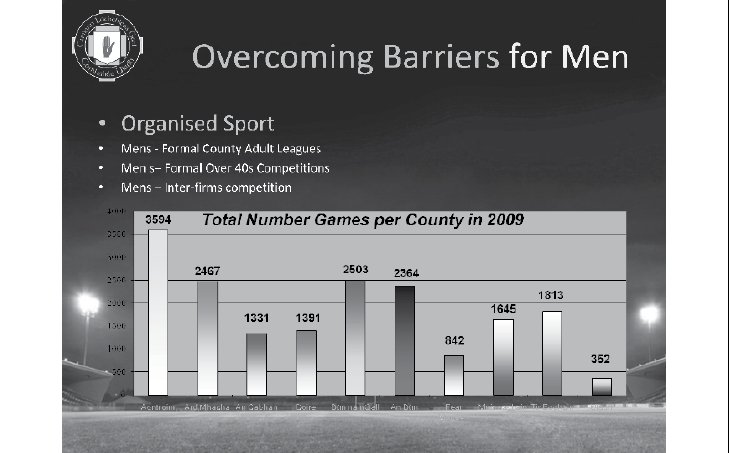

Men

95. While men are not identified as a group with lower levels of participation than average, the inquiry found that there are a number of barriers specific to men taking part in sport and physical activity.

96. Evidence provided by the Public Health Agency suggests that men aged 30-50 tend to be too busy with work and family to make room for physical activity. Men may also be under the impression that only ‘gruelling and uncomfortable’ forms of physical activity are worthwhile. Other men view their own health as a low priority and therefore are not motivated to participation in physical activity for the health benefits.

97. Information obtained from the Finnish Government also pointed to some of the barriers encountered by males in terms of participation. The Committee was informed that the Finnish Government had identified men over 40 with children as having lower levels of participation:

In Finland, the Ministry of Education’s Sports Division identified men in their mid- 40s with children as having a lower than average level of participation in sport and physical activity. In Finland there is a tendency that women are active in individual sporting activity such as jogging, swimming, running and Nordic walking, whereas men in Finland remained physically passive. The discussions with Mr Tolonen found that due to cultural expectations, men took the main role in the care of children during their leisure time while they were not at work.

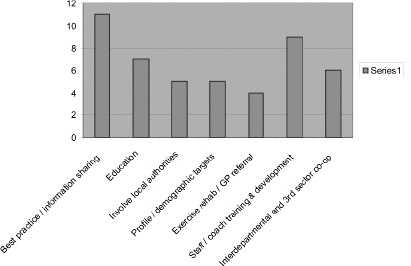

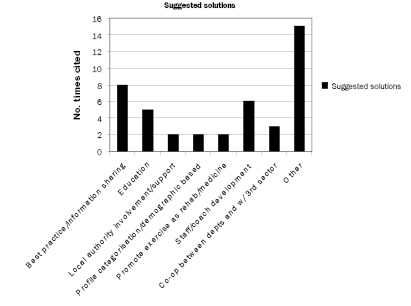

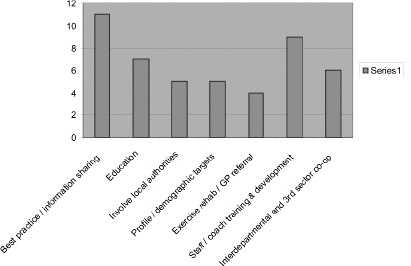

Chapter 4 — Solutions

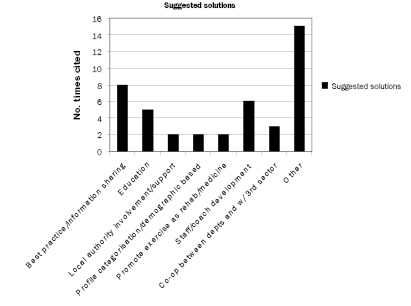

98. In this chapter a range of solutions are set out for both increasing levels of physical activity across the adult population as a whole, and among specific groups with lower levels of participation. These solutions are based on the evidence presented to the Committee, including examples of good practice from other countries and regions.

The need for a cross departmental approach

Involvement of all departments and leadership from the Executive

99. In the foreword to Sport Matters: The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation 2009-2019 the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure states that its implementation will require a joined up approach across government departments and other stakeholders. This key point was echoed by many organisations who submitted evidence to the inquiry including Sport NI:

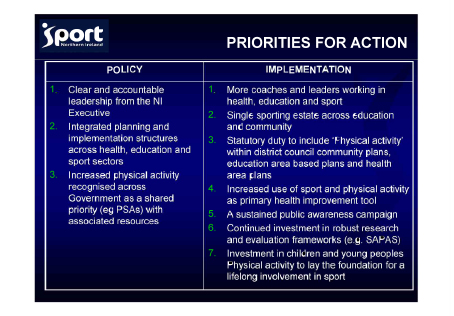

The Sport Matters strategy proposes the creation of a strategic monitoring group, which would be chaired by the Minister and would involve senior representatives from all Departments. A key issue is to get physical activity and participation placed on the agenda of all Departments rather than residing solely with the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. The resources, ideas, controls and influence are not all in one Department; rather, they exist across a series of Departments.

100. The WCRP, Craigavon Borough Council, NILGA, the Big Lottery Fund and the BMA were also in favour of a cross-departmental approach. The BMA provided a number of examples as to how other government departments have a role to play:

However, at the outset, we want to say that tackling levels of physical inactivity requires a cross-departmental and cross-sectoral approach, and we encourage government Departments to play their role . . . At government level, all Departments have a role to play in planning and working with education providers and the health and leisure industries. Indeed, they have a role in planning future housing, parks, road services and transport policies. All of those need to be integrated in order to impact on people and change their behaviour.

101. Similarly, Ulster GAA stated that there are seven government departments which have an impact on the delivery of sport and physical activity, and provided a detailed assessment of the roles of the various departments:

The Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure has to be the lead Department since it is directly responsible for sport and physical recreation. Its responsibility includes the role of Sport NI, which, as part of its remit, deals with the governing bodies through the Northern Ireland Sports Forum. The Department for Social Development is responsible for regeneration, social exclusion and a number of other areas.

The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety is the single biggest beneficiary of the work of sporting bodies, because, if more people participate in sport, that should ultimately engender a healthier society. If that is achieved, the Health Department will be a significant beneficiary. The Department of Education has several roles to play, because, as Eugene said, sport, in curriculum, is part of the future development of any positive education programme. I also feel that that the Department has access to the single biggest estate outside that controlled by local authorities and governing bodies, and its facilities are significant.

The Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister also has a responsibility, because it sets policy on equality in several areas, including equality for people with disabilities and those from ethnic minority backgrounds. OFMDFM has a responsibility in the delivery of a shared future.

The Department for Employment and Learning has a role to play. That might seem strange, but it is responsible for delivering part of the safety at sports grounds legislation, because the training requirements for stewards, supervisors and safety officers will have to include qualifications. Those requirements are being set at NVQ level 2 for stewards, NVQ level 3 for supervisors and NVQ level 4, which is currently unavailable, for safety officers. The Department for Employment and Learning will also have a programme running under SkillsActive, which could be exceptionally helpful in developing local community volunteers and recognising their accreditation.

The Department of the Environment has a significant role, because it is responsible for the reorganisation of public administration and for local government. Therefore, it is responsible for the provision of facilities by local government and the provision of sport within the remit of local authorities. All of that is essential to building a wider sporting consciousness and building facilities for the playing of sport.

102. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group event also argued that a joined up approach is needed:

Cohesion is required among government departments, especially between DCAL, DHSSPS, DETI, DENI, DRD, DARD and DOE. Support the introduction of a single body with a remit for addressing the health-living/physical activity nexus as a whole, or the introduction of an interdepartmental forum to develop policy intervention.

103. In his evidence to the inquiry, the Minister recognised the importance of the cross-departmental approach to increasing participation levels. He also made the point that other departments need to be prepared to contribute resources to this end:

However, it is important for central government and the Northern Ireland Assembly to set the example. If the Executive are to fulfil their commitments to sport and physical recreation in Sport Matters and deliver the wider benefits, Ministers and Departments need to look imaginatively at ways of supporting each other practically and financially.

104. In terms of what can be learned from other countries and regions the Committee looked to the evidence from Finland. Finland has been cited as the European model in dramatically increasing its population’s engagement in physical activity and participation in sport. In the mid- 1990s, Finland had the highest heart disease rate in the European Union, but the recently published ‘2010 Eurobarometer survey on EU citizens’ sport and physical activity habits’ found that 72% of Finns are taking regular weekly exercise.

105. The evidence obtained from the audio conference with a Finnish Government official revealed that Finland had taken a cross-deparmental approach to increasing participation levels:

In Finland, a ‘Sport Law’ was established which indicated that the Ministry of Education is responsible for the promotion of sport at a government level through the establishment of the Sports Division within the Ministry of Education. Whilst Education promotes sports and physical activity, other ministries, such as the Ministry of the Environment, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ministry for Traffic deal with its facilitation. This varies from the construction of leisure centres to infra-structure development by way of roads and cycle routes.

Role of the Programme for Government

106. Sport NI suggested that a tangible way to ensure buy-in from other departments would be to allocate them Public Service Agreements (PSAs) around physical activity in the next Programme for Government:

We suggest that including more PSAs in the next Programme for Government and sharing those among departments can make a difference and can enable people to see where they fit in and what role they have to play . . . I would love to see every department having a target on physical activity. There will be no accountability for delivering until we have that, then we can all ensure that there is joined-up working.

107. Ulster GAA expressed a similar view in terms of advocating that sport and physical activity be further embedded in the next Programme for Government:

A cross-departmental approach is required because, although sport is within the remit of this Committee, some of the major involvements and benefits that emerge from sport relate to other Departments: for example; social cohesion, antisocial behaviour, health, education, equality and a number of issues in that area.

Whatever strategy emerges for sport should become the central policy for several departments that are dealing with the outworkings of those items, and sport should then be seen as an arm of delivery. Sport is not specifically referred to in the current Programme for Government, but it is included under several headings, because it is probably the most essential instrument for delivering better interactivity, a better sense of health and better physical preparedness for people to deal with modern society. All of the various issues in the Programme for Government could be dealt with by sport to some degree. We maintain that there are seven departments that have an impact on the delivery of sport.

Role of DHSSPS

108. In addition to the general point that a range of government departments have a role in increasing participation levels, particular reference was made to the potential for the DHSSPS to impact in this area.

109. Sport NI made the point that DHSSPS could contribute both in terms of resources and in terms of promoting the health benefits of physical activity. On this latter issue Sport NI stated:

One of the key actions that is proposed in the Sport Matters strategy is that sport and physical activity should be seen as primary health interventions. Consequently, GP referral schemes, a number of which across Northern Ireland are successful, would become the norm and part of the prescribing book for every GP in Northern Ireland. People talk about barriers, but sometimes encouragement is all that is needed. A pill need not be taken to lose a bit of weight or to treat blood pressure. A walk would do.

110. On the issue of budget, Sport NI referred to the investment made by the Department of Health in Scotland to promote physical activity in schools:

The Health Department in Scotland is spending £24 million over three years to set up and support an active schools network. The aims of that investment were to encourage young people to become motivated to have healthy and active lifestyles that would support their development into adulthood. There is a lot to be learned from that example of how investing in encouraging young people to be physically active can come from budgets and Departments outside those that deal with education and sport.

111. Likewise, the Minister stated that DHSSPS had the potential to make a major contribution given the size of its budget as compared to that of DCAL:

People often talk about partnership and cross-departmental working, but that is of value only if one brings something to the table. DHSSPS can bring certain things to the table . . . 80% of our budget goes to arm’s-length bodies, but, even when it is all brought together, it makes up a very small part of government. The biggest return will be achieved by bringing in other Departments, particularly the Department of Education and the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. If we get full buy-in there, we will start to see delivery.

112. Based on the evidence, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

We recommend that the Executive prioritises the need to increase participation in sport and physical activity and accordingly provides the necessary funding to implement ‘Sport Matters: The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation, 2009 – 2019’ in the next Comprehensive Spending Review.

We recommend to the Executive that the next Programme for Government contains Public Service Agreements for all relevant government departments in relation to actions aimed at increasing participation in sport and physical activity.

We recommend that the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) invests more of its budget in preventative health measures which involve participation in physical activity, as a means of reducing obesity related illness and the associated financial cost to the health service over future years.

Sport and physical activity for children and young people – the need to begin early

113. One of the key messages which came through from the evidence was that the likelihood of an adult taking regular exercise was very much influenced by their experiences of sport and physical activity as a child. People who take part and enjoy exercise as a child tend to keep the habit into adulthood. This was mentioned by Fitness NI, delegates at the stakeholder conference and the BMA among others. The BMA put it very simply:

If an active lifestyle starts in early childhood, it is much easier to keep up.

PE in schools

114. Many of those who gave evidence to the inquiry lamented the fact that in lots of schools children are not being given the opportunity to do 2 hours PE a week as per the government guidelines.

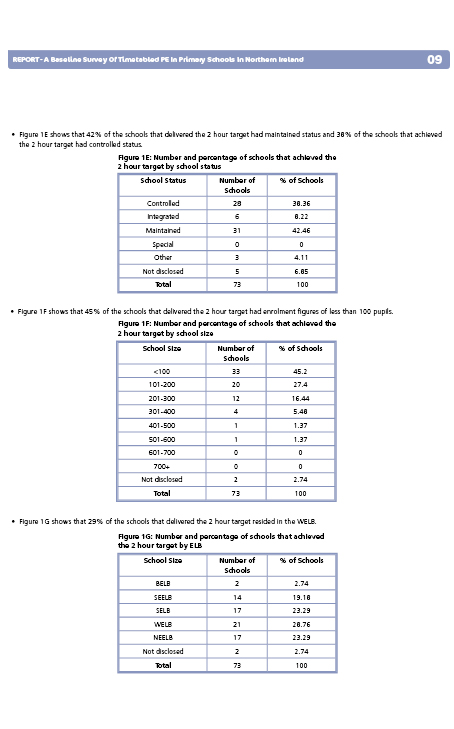

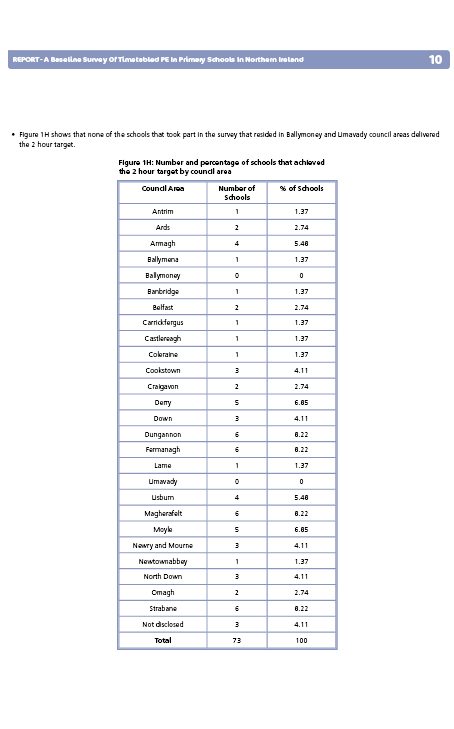

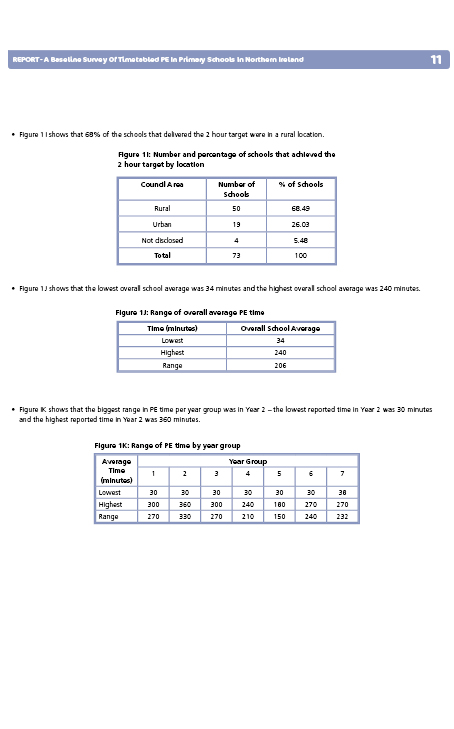

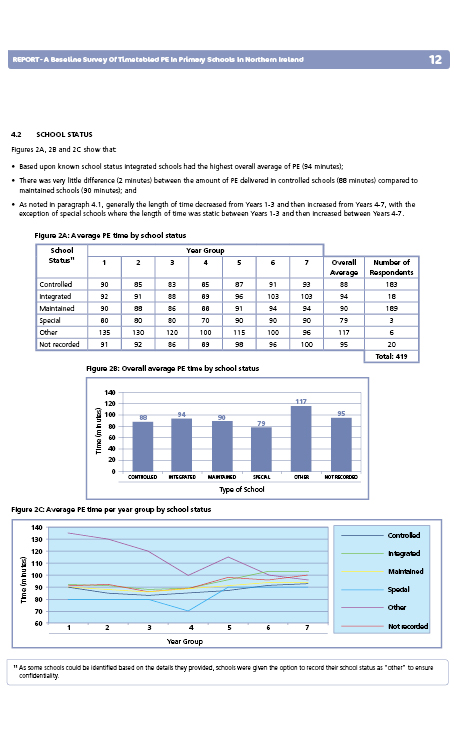

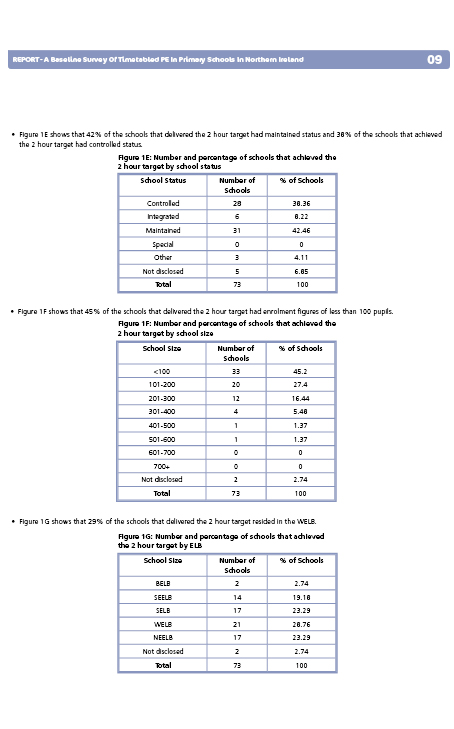

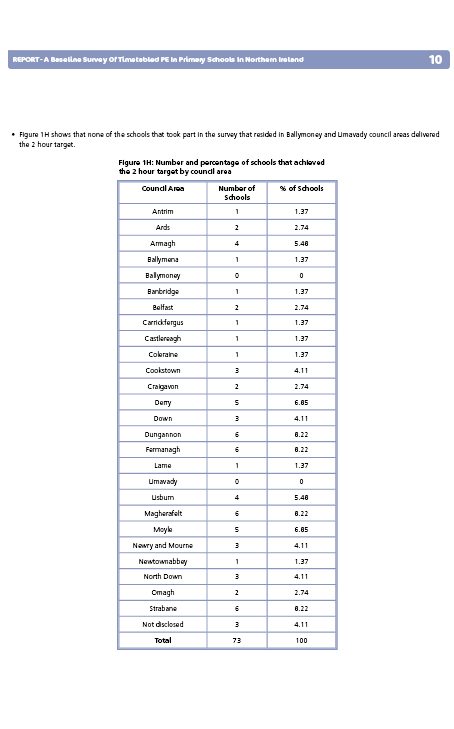

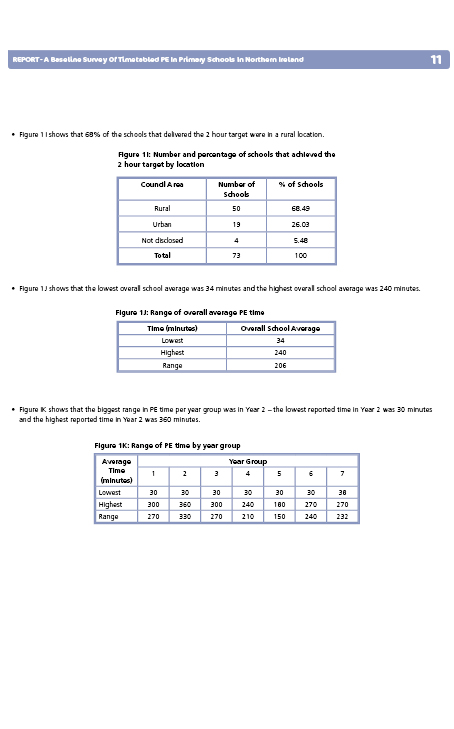

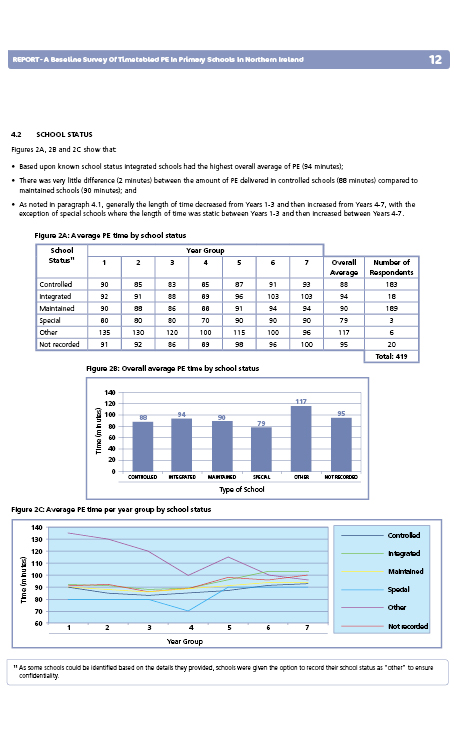

115. A recent survey conducted by Sport NI revealed that only 17% of primary schools are providing 2 hours of PE a week. Sport NI explained that while the Department of Education sets a target of 2 hours a week for schools, it does not have the power to set time standards for any particular subject – it is up to individual schools to devise their own timetables.

116. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group event were also concerned about the level and type of PE being offered at schools:

The PE curriculum should be re-examined to ensure adequate levels of activity take place in schools and that the activities available encourage inclusive participation.

Physical Education in schools should become more varied, with a greater focus on non-competitive activities.

117. Likewise, Sport NI suggested that PE does not need to be competitive, as did the BMA who made the point that in some cases enjoyment is missing from the traditional concept of PE:

Education, in the classical sense, is very important, and that goes back to the interdepartmental aspect of the issue. It is about motivating children to exercise and getting them used to it. I was struck by a paper from Finland, where they have the concept of a joyful model of sports schools teaching for 4- to 13-year-olds. I asked myself how joyful my sports education at that age was. It was not; a tiny minority of us rushed about and had great fun, but most did not.

118. The importance of PE as the foundation for physical activity in adulthood was emphasised by the Scottish Health & Sport Committee in its Report on Pathways into Sport and Physical Activity. The news release accompanying the publication of the report stated:

There has been a lamentable failure to deliver the target set in 2004 for two hours’ quality physical education for every school pupil, according to a report published today by the Scottish Parliament’s Health and Sport Committee.

In its Report on Pathways into Sport and Physical Activity, the committee recognises PE as the only comprehensive way of ensuring that all children and young people have the skills to lead a physically active life. It is highly critical of education authorities and HM Inspectorate of Education for failing to give PE the same status as other curricular subjects.

119. A research paper commissioned by the Committee made similar points in relation to the provision of PE in schools in the EU:

- Sport and PE were in a state of neglect, with less time allocated to them in the timetable and the diversion of resources away from them towards other subject areas;

- PE/Sport were often afforded lower prestige than other subjects; and

- In most countries, PE curricula focussed almost exclusively on competitive sports, as such a curriculum based around physical activity and non-competitive sports were deemed to be ‘unthinkable’ in most regions.

120. In Finland the government has recognised the importance of school based PE and acted accordingly. Information obtained from the audio conference with the Finnish government official revealed that Finland has made it mandatory for all children up to the end of their compulsory education to have 2 hours of physical activity per week.

121. Currently the Finnish government is trying to increase the amount to 3 hours per week and increase physical activity in before and after-school clubs. They are also looking into a minimum of two hours per day of different physical activities for 12 year olds and under and one hour per day minimum for children in second level education. This is hoped to be achieved by having physical activity incorporated into other subjects taught in schools other than PE.

Clubs/schools links

122. During the inquiry the Committee was informed that when young people leave school there is often a drop-off in terms of their participation in sport and physical activity. The Committee was encouraged by the work sporting organisations are currently doing to help young people stay active as they make the transition from school to higher education or work.

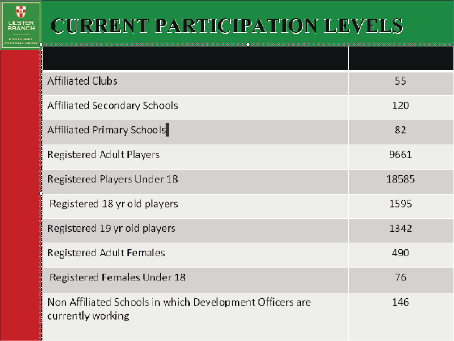

123. For example, Ulster Rugby provided the Committee with a practical example of how it had adapted its structures to encourage more young people to stay in the game once they left the school environment:

This year, we have specifically identified an under-19 league. We researched the situation and discovered that there was a problem with progression from under-18 rugby to adult rugby because the under-18 rugby was played on a Saturday morning and there was no engagement with the adult population of the clubs. When the under-18 players moved across, they felt that they were not welcome, and they had not transcended that. We have developed a league that will straddle that divide and play its games on a Saturday afternoon. In that way, the players will become part of the club environment and, by the time they move into adult rugby, will know the people with whom they are playing.

124. The IFA also provided evidence of work it is doing with schools, in particular with young girls at primary schools, to encourage them to become involved in football:

Interestingly, the biggest area of growth has been in primary schools, much of which has been down to the soccer role models courses that the women’s department runs. In those courses, senior players from the international side go into primary schools and coach children. The courses are not just about football; there are positive health messages about staying involved in football, and there is a role-model aspect, hence the name. Women’s participation has probably been our fastest area of growth over the past 10 years.

125. Likewise, Ulster GAA was of the view that it is crucial to keep young people involved in sport and physical activity during their latter teenage years, and that they should be required to continue with PE until they leave school:

Young people are only required to take part in PE until they are 16, but I think that they should be required to participate in some sort of activity, such as keep fit, until they are 18. That is one of our recommendations.

Young people start to drop out of physical education at 16, 17 and 18. They are out the door, and they are not really as interested in sport as they once were. Therefore, the structured environment of formal education provides an opportunity to ensure that young people continue to take part in physical education until they leave school, and perhaps, once they get older, they will want to continue with that.

126. The Committee welcomed the fact that greater integration of schools and clubs is one of the goals of Sport Matters and that there are specific targets to establish 20 School Club Partnerships and to appoint 40 Club Support Officers across Northern Ireland.

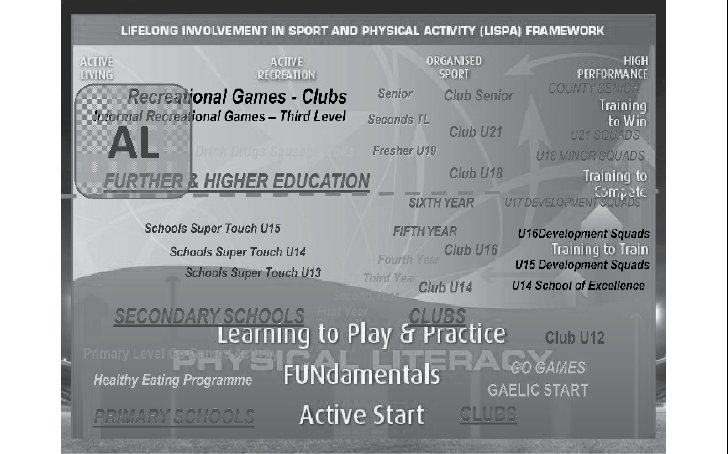

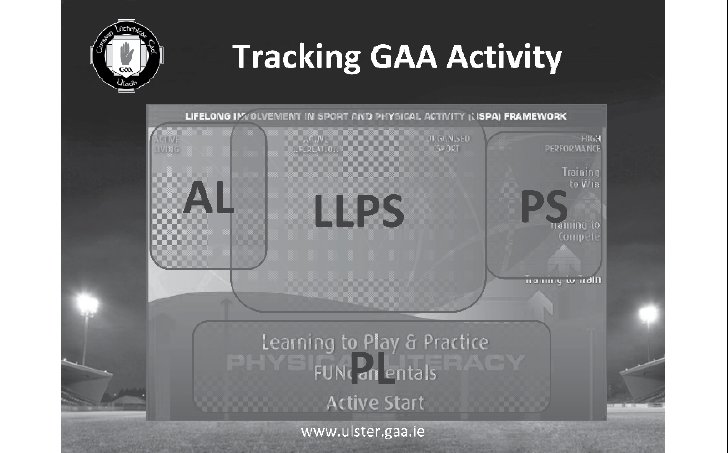

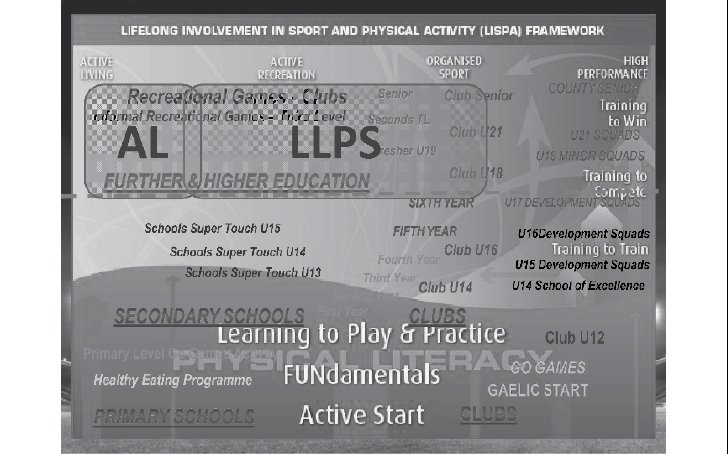

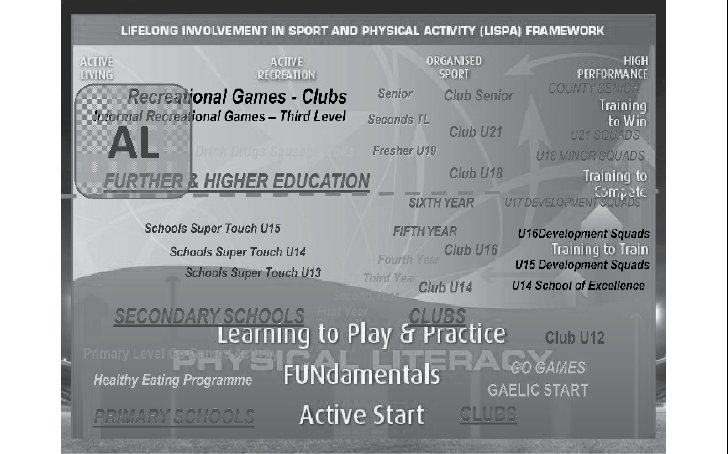

Lifelong participation in sport and physical activity

127. The Committee welcomes the vision set out in Sport Matters:The Northern Ireland Strategy for Sport and Physical Recreation 2009-2019 which is “a culture of lifelong enjoyment and success in sport”. Sport Matters identified both physical literacy and lifelong physical activity as the ingredients for increasing participation levels.

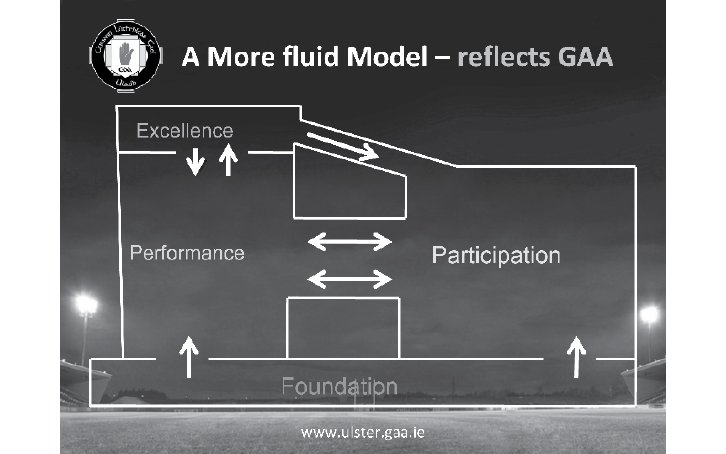

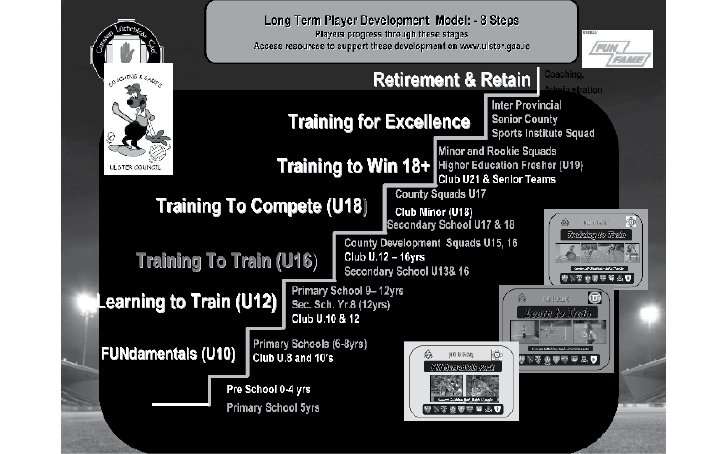

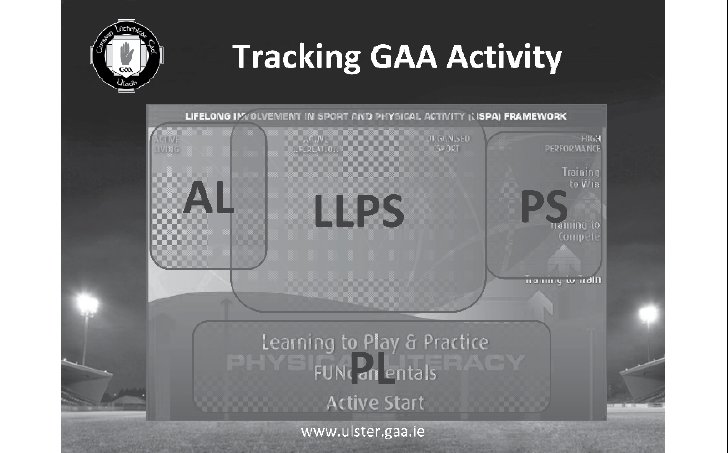

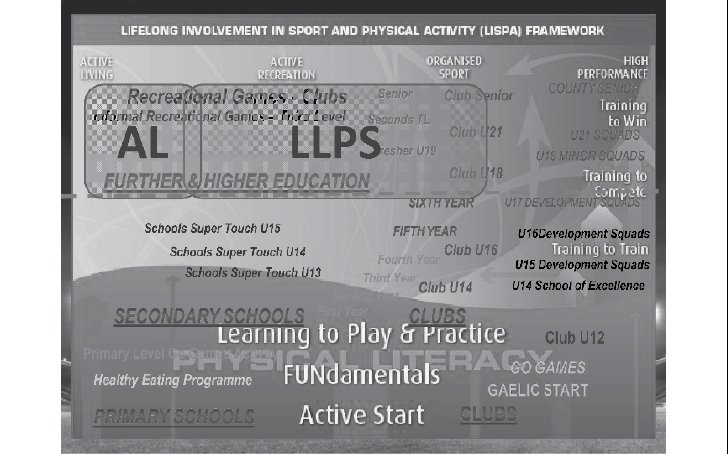

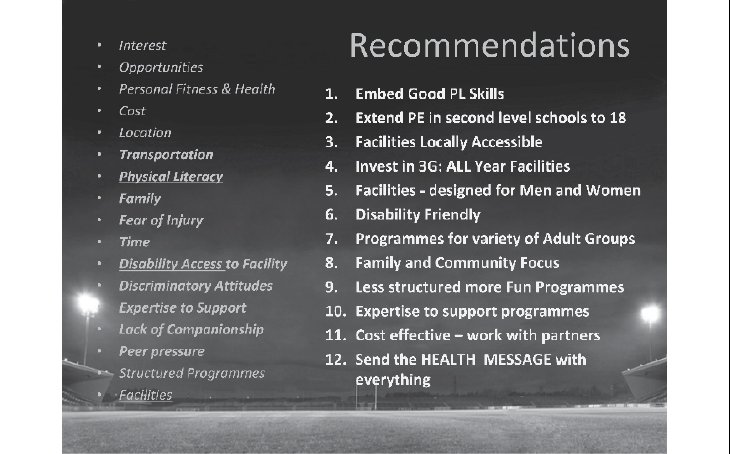

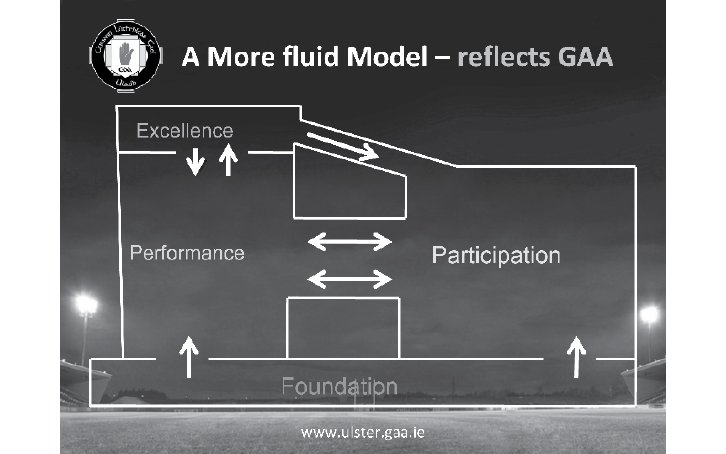

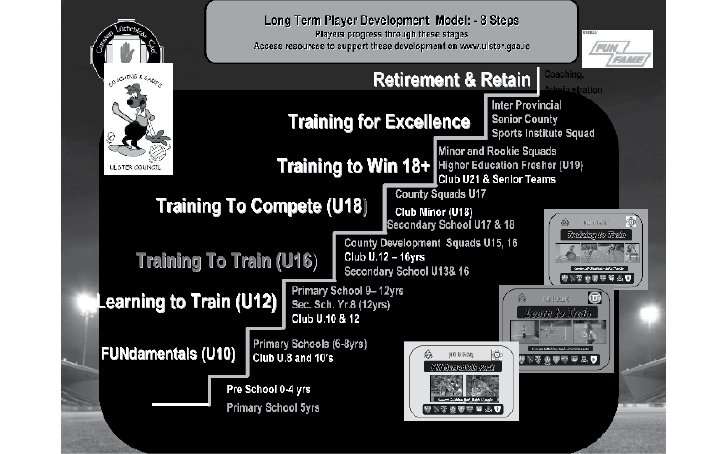

128. The Committee was particularly impressed with the work being carried out by Ulster GAA in terms of providing participation opportunities for people from “the cradle to the grave”. Ulster GAA informed the Committee that they had developed a model which recognised that people can move through different stages of involvement in sport through the different stages of their lives:

The model that we are working on reflects how people who are involved with Gaelic games can move quickly from participation to performance and then to excellence. Once they have finished at the excellence level, they can move back down to performance and participation.

129. The GAA has developed programmes to keep adults involved in the sport once their more “competitive” years are over:

Over the past three or four years, we have been developing a recreational Gaelic games programme for men over 40 who can operate between or within clubs. As I said earlier, the challenge is the fear of injury. We have tried to get around that by adjusting the rules to make the sport non-contact — one-touch or two-touch football.

Accessibility of programmes and facilities is crucial for female uptake and reference is made in our presentation to Gaelic 4 Mothers, Gaelic 4 Girls, Chicks with Sticks and Hens with Hurls for the over-40s. Those initiatives form the female-friendly approaches to Gaelic football and camogie.

130. The Committee also welcomed the way in which the the GAA is using its facilities in an imaginative way to encourage lifelong participation in physical activity, not necessarily in gaelic games, among those involved with the clubs:

Many of our clubs now have walking tracks around their perimeters, which is a simple way to encourage female participation, particularly in rural areas, where the club’s floodlights provide a safe environment for females to exercise. That is a very simple way of how clubs use their facilities to ensure lifelong female participation away from the games themselves.

131. The Committee was of the view that the GAA is a model of good practice in terms of providing opportunities for lifelong participation and would encourage other governing bodies to follow suit.

132. Based on the evidence, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

We recommend that the Department of Education is more pro-active in terms of assisting schools to meet the target of providing 2 hours of Physical Education (PE) per week. We recommend that the Department of Education makes it an urgent priority for primary schools to meet this target.

We recommend that governing bodies of sport review how they can work more closely with schools to ensure that structures are in place to encourage young people to continue participating in sport and physical activity once they leave formal education.

We recommend that sport governing bodies put in place structures to facilitate lifelong participation in sport and physical activity for their members. The Committee points to the good work being done in this area by the GAA as a model of best practice.

Facilities

133. It is recognised that having access to high quality facilities is key to increasing participation in sport and physical activity. Indeed “Places” is one of the three key strands of Sport Matters along with “Participation” and “Performance”.

134. Local government authorities are one of the key providers of leisure facilities. In its evidence to the inquiry, Sport NI emphaised how the community planning function envisaged under the Review of Public Administration (RPA) should be used by local councils to increase particiaption:

Well-being is so linked to physical activity that it would be totally inappropriate if community plans did not involve elements to make the community more active.

Sport NI feels that the way to get local authorities to take the issue seriously is to ensure that physical activity has a statutory requirement in community plans. I am not saying that they do not take it seriously, but, if it is made a statutory requirement, those authorities will have to plan for and deliver on it.

135. However, given the uncertainty around timescales for the implementation of the RPA, the Committee was of the view that local councils should conduct an audit of the facilities currently available in their area with the aim of maximising their use to promote increased levels of participation.

136. The inquiry also pointed to the fact that government departments have substantial areas of land under their control which could potentially be used for sport and physical recreation purposes. Sport NI made the following point on this issue:

We also look at the huge amount of publicly owned land, and we propose that it should be open for people to engage in physical activity.

As you quite rightly said, some of the activities do not involve a lot of money. For example, the public estate in Northern Ireland is controlled by many different Departments, and there is an opportunity to open that estate up for physical activity, which would cost very little. There would be some management costs, but it would provide a great deal of opportunities.

137. Likewise, Sport Matters identifies the need to:

Review and update relevant public policy frameworks to enable access to, and sustainable use of, publicly-owned land in NI for sport, physical recreation and activity tourism.

138. On the question of maximising publicly owned land and facilities, a number of organisations stressed the potential of the school estate to be opened for community use. Sport Matters refers to the “Six Acre Standard” which is a bench mark for the provision of outdoor sport and play areas. The standard proposes that there should be four acres for structured outdoor sports and two acres for outdoor play/green spaces per 1000 head of population. Northern Ireland currently achieves 53% of the standard, however, by making available all existing education facilities, this figure would increase to 81%.

139. Delegates at the stakeholder focus group event suggested that opening up the school estate was one of the key solutions for increasing participation. The Ulster GAA made the following point on the matter:

To have facilities lying empty from 5.00 pm when two or three local clubs are struggling to find facilities for any type of participation is — I will not say scandalous, but it must certainly be looked at very seriously.

140. The Big Lottery Fund provided the Committee with an example of a successful programme it had run which provides schools with enhanced PE facilities on the condition that they are also made available for community use:

I will speak about the New Opportunities for PE and Sport programme.

Except for the smallest projects, wider community benefit and use are an essential part of grant schemes in the PE and sport programme. There were 136 projects funded through that programme, which included the provision of purpose-built early years play areas with equipment, storerooms, changing facilities, large multi-use games areas and larger sports halls. The facilities will support a wide range of games, including soccer, basketball, rugby and Gaelic games. The projects aim to increase the amount of time available for physical activity and the participation of all pupils before, during and after school.

Many schools are booked out in the evenings and at weekends, and some even have a waiting list for the use of their facilities by the wider community.

In the design of that programme, we were very specific that, in all but the smallest projects, there had to be community use of those schools as part of the requirement for the delivery of each of those projects. That was an important way of illustrating the emphasis on making sure that the school estate was open where possible.

141. Facilities for sport and physical activity do not just include leisure centres, sports halls and pitches. They also include the outdoor environment of cycleways and walkways. These sorts of facilities are particularly important for those people who prefer to take part in informal physical activity and do not wish to be part of a sporting club. Delegates at the stakeholder conference stated that there needs to be improvement in cycling and walkways. The Big Lottery Fund referred to the funding it had provided in this respect:

For individuals who may prefer not to get involved in group activity, our environmental programmes have funded a much broader range of physical facilities, such as walking and cycling routes. At the largest scale, the Connswater Community Greenway was a huge investment in east Belfast, and that project will provide bridges and cycle routes.

142. Sport NI also talked about the need for more dedicated cycle paths, and also for cycle lanes to be designed in such a way that they are not situated on or lead to sections of busy roads:

We need more schemes such as the greenway that was mentioned to take cycle tracks into the heart of local communities, rather than providing spurs that link to main roads. Those result in children getting to main roads and suddenly being confronted with several hundred cars whizzing past at 50, 60 or 70 mph.

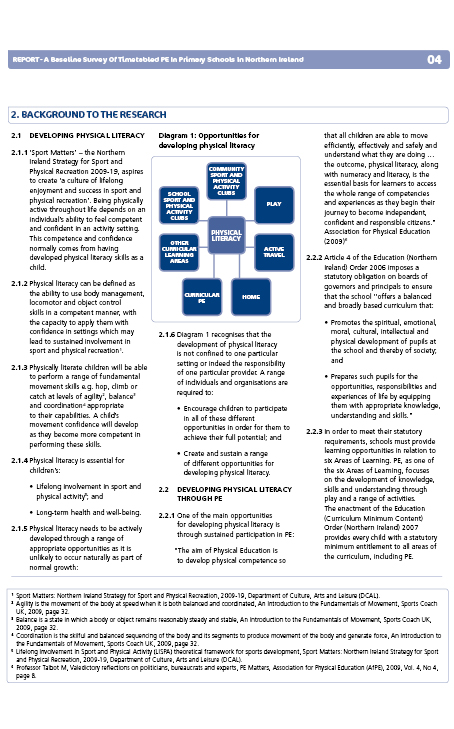

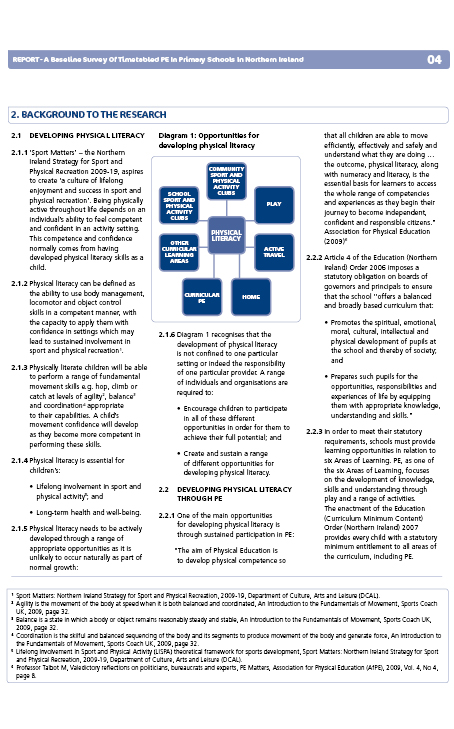

143. The Committee also discussed the fact that many of the National Cycle Network routes, while on what would be described as quiet country roads, are roads nonethless where the national speed limit applies. There are concerns that motorists are not aware that the road forms part of the National Cycle Network and therefore are not on the alert to look out for cyclists and adjust their driving accordingly. Therefore, the Committee was of the view that the Department for Regional Development should address this issue by reducing speed limits on these roads and/or providing warning signage for motorists.