Session 2007/2008

First Report

Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

Report on the

Draft Sexual Offences

(NI) Order 2007

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

AND WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS RELATING TO THE REPORT

Ordered by Ad Hoc Committee to be printed 21 January 2008

Report: 15/07/08R (Ad Hoc Committee)

Ad Hoc Committee on Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007

The Committee was established by resolution of the Assembly under Assembly Standing Order 48(7) on Monday, 3 December 2007. The terms of reference of the Committee were to consider the proposal for a draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007, referred by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and to submit a report to the Assembly by 4 February 2008.

The Committee had eleven members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson; its quorum was five. The membership of the Committee was as follows:

Dr Stephen Farry, Chairperson

Mr Jim Wells, Deputy Chairperson

Mr Mickey Brady Mr Declan O’Loan

Rev Dr Robert Coulter Ms Sue Ramsey

Mrs Dolores Kelly Mrs Iris Robinson MP

Ms Jennifer McCann Mr Alastair Ross

Mr John McCallister

It was agreed by the Committee that where members were unable to attend meetings they could nominate MLA colleagues to do so. Two members, Mr Roy Beggs and Mr Alex Easton, participated on the Committee on that basis.

The report and proceedings of the Committee have been published by the Stationery Office by order of the Committee. All publications of the Committee have been posted at http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk/ the website of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Contents

Acknowledgement

Introduction and Background

Coverage of the Draft Order

Findings and Recommendations

List of Recommendations

Appendix

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix

Written Submissions and other Correspondence Considered by the Committee

Appendix 4

List of Witnesses

Appendix 5

Contents of the Draft Order 119

Acknowledgement

The Committee wishes to convey its appreciation to all who provided it with evidence and advice, sometimes at very short notice. It would not have been possible to produce this considered response to the legislative proposal without such committed and willing participation.

Introduction and Background

1. This report represents the work of the Ad Hoc Committee on the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007.

2. The Committee was established on Monday, 3 December 2007 by resolution of the Assembly, with the following terms of reference:

To consider the proposal for a draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007, referred by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and to submit a report to the Assembly by 4 February 2008.

3. The Committee has eleven members, with a quorum of five. A permanent Chairperson was elected on 14 December 2007, and a Deputy Chairperson on 8 January 2008. The membership of the Committee is as follows:

Dr Stephen Farry, Chairperson

Mr Jim Wells, Deputy Chairperson

Mr Mickey Brady Mr Declan O’Loan

Rev Dr Robert Coulter Ms Sue Ramsey

Mrs Dolores Kelly Mrs Iris Robinson MP

Ms Jennifer McCann Mr Alastair Ross

Mr John McCallister

4. It was agreed by the Committee that where members were unable to attend meetings they could nominate MLA colleagues to do so. Two members, Mr Roy Beggs and Mr Alex Easton, participated on the Committee on that basis.

5. The first meeting of the Committee took place on 6 December 2007, when decisions were taken in relation to the initial calling of witnesses and the arrangements for subsequent evidence-taking. Dr Stephen Farry MLA was elected as temporary Chairperson.

6. At its meeting of 14 December 2007, the Committee elected Dr Farry as permanent Chairperson and subsequently at its meeting of 8 January 2008 it elected Mr Jim Wells MLA as Deputy Chairperson.

7. At its meeting of 14 December 2007, the Committee was given a background briefing on the draft legislation and the various consultations which had preceded it by a member of the Assembly Research staff. This was followed by a presentation on the Draft Order by NIO officials.

8. The Committee met in all on five occasions between 6 December 2007 and 21 January 2008, during which time it developed and discharged a programme of work. Finally, it agreed its report to the Assembly at its meeting of 21 January 2008.

9. The minutes of proceedings of the Committee are shown at Appendix 1 and the record of the evidence given is shown at Appendix 2. The Committee was assisted by a researcher, Ms Fiona O’Connell, whose appreciation of the legislative proposals was given by way of oral advice. This was supported by two papers which are included at Appendix 3.

10. The Committee was cognisant of the fact that the Northern Ireland Office had already undertaken a recent extensive consultation exercise on its proposals to reform the law on sexual offences in Northern Ireland. There were some 65 respondents. The Committee as part of its deliberations was able to access useful summary and statistical material in relation to this.

11. Mr Paul Goggins MP, Minister of State for Northern Ireland, wrote to the Speaker on 19 November 2007 referring the proposed Draft Order to the Assembly under Section 85 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. Under the legislation the consultation process was limited to 60 parliamentary sitting days effective from 20 November 2007 - the date of publication of the proposals - and running to 5 February 2008.

12. The Minister of State met with MLAs on 26 November 2007 to brief them in person on the details of the Draft Order. The proposals are the result of the first ever comprehensive review of sex offences in Northern Ireland and are similar to earlier (2003) legislation enacted for England and Wales.

13. The effects of the Order, as summarised by the Minister, are as follows:

- All offences will be gender-neutral and, in the main, consensual sexual activity between adults in private will not fall within the criminal law.

- All non-consensual sexual activity and sexual activity involving children and other vulnerable groups will be criminalised and attract appropriately robust sanction.

- There will be clearly defined offences.

- The Order puts children and young people at the centre of the proposals with new offences designed to protect the most vulnerable.

- It includes new offences designed to protect children from abusive behaviour in the home. (Child sexual abuse is most prevalent in the home or extended family).

- It equalises with the rest of the UK the age at which young people can have their consent to sexual activity recognised by the law.

- It ensures that other vulnerable groups will also benefit from the added protection.

- It strengthens the law on commercial sexual exploitation, including offences related to prostitution.

14. Copies of the Draft Order and Explanatory Document issued by the Northern Ireland Office are available on the NIO website at http://www.nio.gov.uk/

Coverage of the Draft Order

15. The proposed Draft Order is the outcome of the first fundamental review of the law on sexual offences in Northern Ireland. Its aim is to achieve a “strengthened, modernised and harmonised body of law, based on the (Westminster) Sexual Offences Act 2003”[1] which was itself informed by extensive and fundamental research. One of the affects of this Order will be to incorporate within the statute those provisions of the 2003 Act which currently apply to Northern Ireland, with the exception of trafficking offences (Sections 57 – 60 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003).

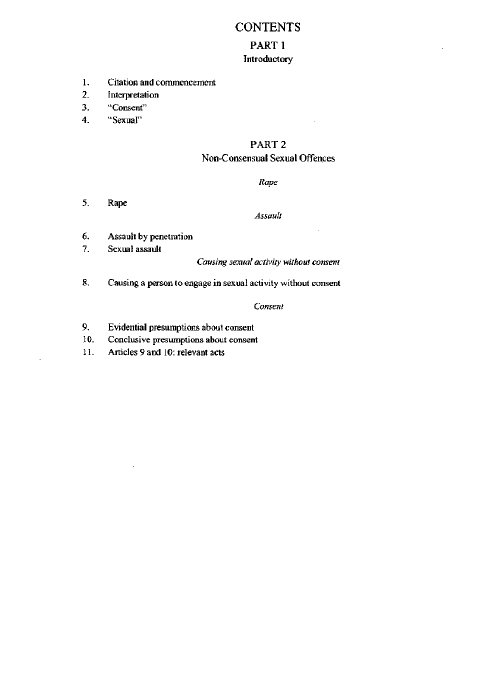

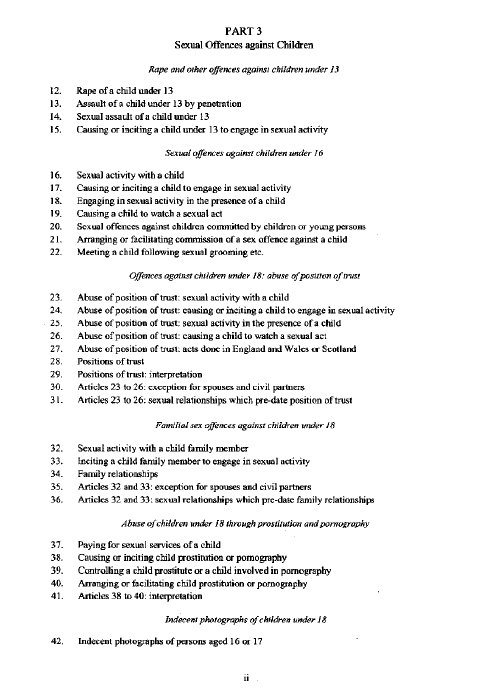

16. The Order, which may be commenced by order of the Secretary of State, is structured into seven parts as follows:

17. The first of these, Part 1, is introductory and, inter alia, deals with key definitions such as “sexual”, “consent” and “touching”.

18. Part 2 deals with the non-consensual offences of rape, assault by penetration, sexual assault and causing a person to engage in sexual activity without consent. Rape is here redefined and new offences created. This part also provides for new evidential and conclusive presumptions about consent.

19.Part 3 deals with sexual offences against children under 16 and makes it as easy as possible to prosecute these. The offences of rape and assault can now be used in cases involving children under 13 without the issue of consent arising. The presumption is that children under 13 do not have any capacity to consent to sexual activity. There are also proposals relating to offences where adults are in a position of trust, such as those employed in a residential home, detention centre or an educational establishment. There are proposals to deal with sexual offences committed by family (or extended family) members and there are provisions for offences dealing with exploitation through prostitution and pornography which are aimed at protecting children up to 18.

20. Provisions in the Protection of Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 and the Criminal Justice (Evidence, etc) (Northern Ireland) Order 1988 are amended to give protection to children up to 17 years of age in relation to indecent photographs.

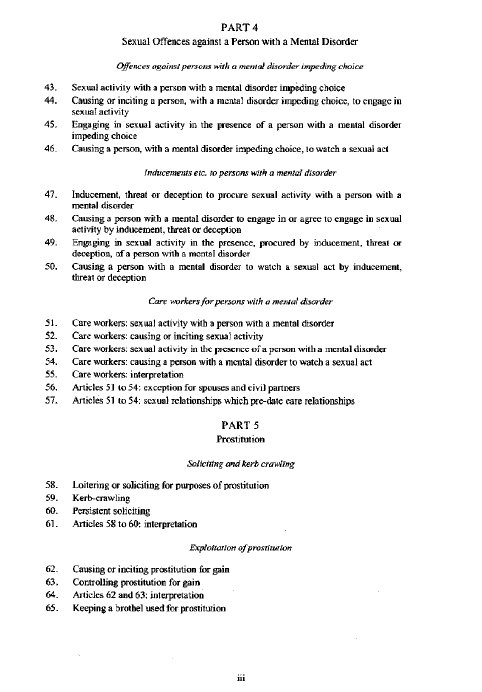

21.Part 4 deals with sexual offences against persons with a mental disorder.

22.Part 5 deals with prostitution and includes new offences of loitering or persistent soliciting and kerb-crawling. These offences aregender-neutral.

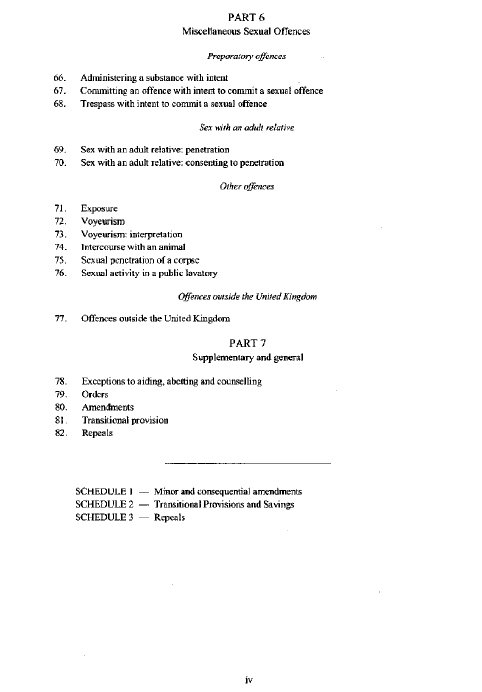

23.Part 6 deals with miscellaneous sexual offences, including preparatory offences that apply whether or not an intended sexual act occurs. There are other miscellaneous offences including exposure, voyeurism, sexual penetration of a corpse and sexual activity in a public lavatory.

24. This part also allows for the prosecution in Northern Ireland, where the offender is domiciled here, of offences against children under 16 that were perpetrated elsewhere.

25.Part 7 is the final part which deals with some exceptions, powers of the Secretary of State, amendments and repeals.

26. Appendix 5 ofthis document provides a more precise listing of the contents of the Draft Order.

Findings and Recommendations

27. The first point to be made is that the Order is in essence about the sexual offences themselves – it is not about victims or sentencing. It contains some 19 offences already extending to Northern Ireland by way of Part 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, and 36 new offences.

28. The Committee recognises that sexual behaviour is a complicated social phenomenon which is not determined merely by what is written into statute. Different regions in different countries have different social climates.The Committee believes that in general terms the sweep of the legislation is sound and that it is the right approach to take, with the exception of the age of consent issue. There is within it a particular regime created for those aged 13 – 16 whichbecause of our view on the age of consent, discussed later, we would wish to see applying to 13 – 17 year olds. There is also a further set of protections beyond this, particularly with reference to those in positions of trust. All this is to be welcomed.

29.The Committee welcomes the codification of the law on sexual offences within a single statute and we welcome increased tariffs for offences, and the move to gender-neutral offences.

30.The Committee welcomes the removal of consent as a defence for sexual activity with a child under 13 and the fact that this now will be regarded as rape.

31.The Committee is averse to the proposed defence of reasonable belief where a child is between the ages of 13 and 18. The removal of this defence, it seems to us (from the evidence given), offers greater protection to children and young people.

32.We welcome the fact that the Order brings clarity to the law on rape, and has an in-built presumption that if violence is used, or if an overpowering drug is administered, that the presumption will be that a rape and not a consensual act has occurred.

33. We heard evidence that the guidance for prosecution, social services and education is not clear, or robust enough, for children who engage in sexually harmful behaviour and that there are issues about resources for any work connected to this. The Committee therefore welcomes the Minister’s evidence that “Effective guidance must be provided to the Public Prosecution Service” and that he wants to ensure that he develops that guidance consultatively and bring into play the views of voluntary organisations and statutory agencies.We believe that there is merit in the development of such prosecution protocols. It is appreciated that it would not be appropriate to include these in the Draft Order, but in the interests of consistency, of justice and particularly of the victims, it is our view that this work should be commenced without undue delay.

34.Protocols should also provide a role for diversionary youth conferencing arrangements (these are unique to Northern Ireland).

35.The Committee was persuaded by arguments in favour of equalising the penalties for causing or inciting abuse of a child through prostitution and paying for the sexual services of a child, and strongly recommends that the Draft Order be amended to reflect this. The perpetrators of both offences each bear a heavy burden of guilt and this should be recognised in the legislation. It is anomalous that a perpetrator of the latter offence could conceivably receive life imprisonment, whereas a person who controls the child might receive only 14 years.

36. Article 76 covers sexual activity in a public lavatory and does so using a modified definition of sexual activity. We believe that in light of evidencean offence of advertising for sexual activity in a public lavatory should form part of this Order.

37. Section 5 of the Criminal Law (Northern Ireland) Act 1967 (CLA) as it stands requires the reporting of an arrestable offence to the police. In this, sexual activity between children is criminalised with a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment. The Committee received evidence that suggests that mandatory reporting of child abuse may be counterproductive and notes that parallel legislation in England and Wales has been repealed.The Committee is of the view that Section 5 should be amended to ensure that young people are not inappropriately penalised for consensual and non-abusing sexual activity.

38.We strongly recommend that the NIO, DHSSPS and key professionals and NGOs establish a forum to develop and take forward policies and practices in this area. There are many interests and there is much scope for misunderstandings in this complex field and there must be a visible process of management and of stakeholder involvement.

39. We are grateful for the Minister’s cake sure that voluntary organisations, statutory agencies and others continue to be involved in the development and outworking of the legislation”.ommitment to a “round table discussion pulling together those in the voluntary and community sector and his officials”; and welcome his statement that “I want to m

40. We note that the positions of trust referred to in the Draft Order do not includesports coaches. The Minister in his evidence to the Committee indicated that “positions of trust” tend to be statutory and that a review in England examined the inclusion of sports coaches and found against this partly on the basis that a range of other non-statutory positions might also have to be drawn into the reckoning.The Committee, while content to acknowledge the difficulties, would strongly urge the Minister to give further serious consideration to the inclusion of sports coaches within the legislation.

41. The Committee wishes to acknowledge the work of the various agencies in dealing with“victims and survivors” of sexual violence, and of the initiative of the Health Minister in announcing Northern Ireland’s first Sexual Assault Referral Centre. The Committee recognises both the limitations of the criminal law, as indeed has the Minister, and the importance of social agencies and strategies in this field.

42. The Committee was divided on the proposal to reduce theage of consent in Northern Ireland from 17 to 16. Competing arguments were put forward by witnesses and consensus could not be reached in Committee on the matter. The Minister, in his direct evidence to the Committee indicated that even if the Committee was unanimous in recommending the status quo, he would still need to be convinced of the advantages of being out of step with England and Wales on this matter. He believes that the burden of proof rests with those who advocate a different age of consent for Northern Ireland.

43. The full text of the evidence given on this matter, which accounted for a substantial proportion of the total evidence given, is contained in Appendix 2. The Committee, in deliberating on the matter, took account of the arguments of the various groups, including evidence as to possible additional risks.

44. The Minister’s view was that “the key issue is that this legislation is about defining when sexual activity is a criminal offence; it is not about saying when young people should be engaging in sexual activity.” He went on to point out that the DHSSPS teenage pregnancy and parenthood strategy, which has been running for some five years, has begun to show some real signs of progress with a reduction of about 25% in teenage pregnancies over the period.

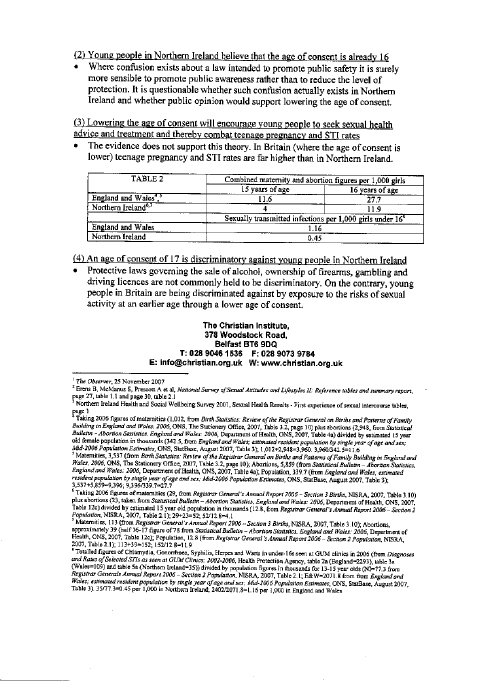

45. The children’s organisations are concerned that the current position prevents young people from coming forward for advice when they are engaged in sexual activity. It has also been argued that if marriage can take place at 16, then on grounds of equality, it is reasonable to have an age of consent at 16. It appears that it is the case that rates of teenage pregnancy in Holland are the lowest in Europe even though the age of consent is 16, indicating perhaps thatstrategy rather than legislation provides the solution, or at least the greater contribution to it.

46. Evidence shows that this is an area of law that is notoriously difficult to sustain in terms of successful prosecutions because it is often one persons word against another.

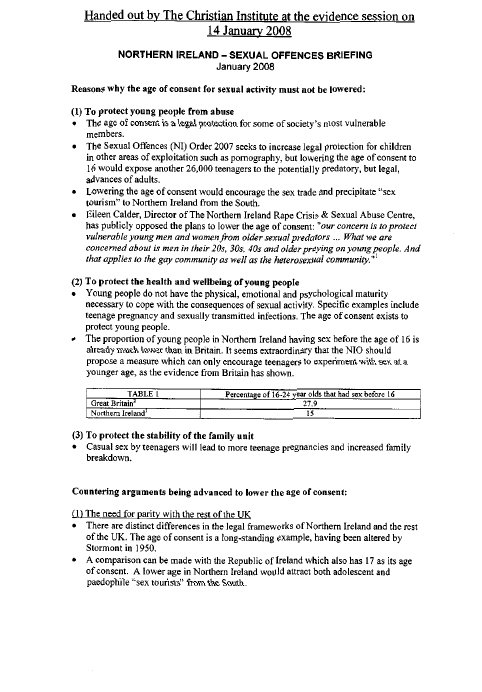

47. The age of consent in the Irish Republic is 17 and there was some concern as to possible consequences of a lowering of the age here which would place some 26,000 additional children in Northern Ireland above the age of consent, and therefore at some additional risk. The Christian Institute argued, among other things, that there is apenumbra effect around the age of consent. In essence it is advanced that convictions tend to be less likely if the age of the victim is slightly below the age of consent.

48. Other arguments posited against change were that the Minister is by no means under any compulsion to make a change, simply because of changes made elsewhere in the UK, and that the Dutch situation, referred to earlier (45), cannot be regarded as something that can be read across without fully taking into account the many differences between the two jurisdictions. The Christian Institute in its evidence also pointed out that where there is an age of consent offence, the prosecution need only prove that a sexual act took place, whereas in cases of rape above the age of consent the issue of consent is a fulcrum of contention.

49. The majority view of the Committee is that the case for a change in the age of consent has not been made. There is no public lobby in Northern Ireland for such a change, and there is nothing to prevent such a change being made in the future if the public and/or its elected representatives can be persuaded of the merits of the case.It is the Committee’s view that the burden of proof rests with those who seek change and not, as has been suggested, with those who oppose it.

50. Therefore,the Committee strongly recommends that there be no change to the current age of consent of 17.

List of Recommendations

- The Committee believes that in general terms the sweep of the legislation is sound and that it is the right approach to take, with the exception of the age of consent issue. Because of our view on the age of consent, we would wish to see the special regime applying to 13 – 17 year olds.(para 28)

- The Committee welcomes the codification of the law on sexual offences within a single statute and we welcome increased tariffs for offences, and the move to gender-neutral offences.(para 29)

- The Committee welcomes the removal of consent as a defence for sexual activity with a child under 13 and the fact that this now will be regarded as rape.(para 30)

- The Committee is averse to the proposed defence of reasonable belief where a child is between the ages of 13 and 18.(para 31)

- We welcome the fact that the Order brings clarity to the law on rape, and has an in-built presumption that if violence is used, or if an overpowering drug is administered, that the presumption will be that a rape and not a consensual act has occurred.(para 32)

- We believe that there is merit in the development of prosecution protocols so that effective guidance is provided to the Public Prosecution Service.(para 33)

- Prosecution protocols should also provide a role for diversionary youth conferencing arrangements.(para 34)

- The Committee was persuaded by arguments in favour of equalising the penalties for causing or inciting abuse of a child through prostitution and paying for the sexual services of a child, and strongly recommends that the Draft Order be amended to reflect this.(para 35)

- An offence of advertising for sexual activity in a public lavatory should form part of this Order.(para 36)

- The Committee is of the view that Section 5 of the Criminal Law (Northern Ireland) Act 1967 should be amended to ensure that young people are not inappropriately penalised forconsensual andnon-abusing sexual activity.(para 37)

- We strongly recommend that the NIO, DHSSPS and key professionals and NGOs establish a forum to develop and take forward policies and practices in this area.(para 38)

- With regard to positions of trust referred to in the Draft Order not including sports coaches, the Committee, while content to acknowledge the difficulties, would strongly urge the Minister to give further serious consideration to the inclusion of sports coaches within the legislation.(para 40)

- The majority view of the Committee is that the case for a change in the age of consent has not been made. It is the Committee’s view that the burden of proof rests with those who seek change and not, as has been suggested, with those who oppose it.(para 49)

- The Committee strongly recommends that there be no change to the current age of consent of 17.(para 50)

[1] NIO Explanatory Document accompanying the proposed Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007, page 7.

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Thursday, 6 December 2007

Room 152, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Roy Beggs MLA (Deputy)

Mr Alex Easton MLA (Deputy)

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA

Ms Sue Ramsey MLA

Mr Alastair Ross MLA

In Attendance: Mr Denis Arnold (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Neil Currie (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Roger Kernaghan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Mickey Brady MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mrs Dolores Kelly MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr John McCallister MLA

Mrs Iris Robinson MP MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

The meeting opened at 10.35am in closed session with the Clerk in the Chair.

1. Apologies

Apologies are detailed above. Mr Easton attended in place of Mrs Robinson. Mr Beggs attended in place of Rev Dr Coulter.

2. Election of Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson

As a large number of Members were unable to attend this first meeting the Clerk proposed, as an interim measure, that a temporary Chairperson be nominated.

Agreed: It was agreed that a temporary Chairperson should be nominated.

The Clerk then called for nominations for the position of temporary Chairperson. Mr Easton proposed Dr Farry. Mr Beggs seconded this proposal and Dr Farry accepted the nomination.

There being no further nominations, the Clerk put the question without debate.

Question put and agreed:

That Dr Farry be temporary Chairperson of this Committee.

Agreed: It was agreed that a permanent Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson would be elected at the next meeting.

The meeting was suspended at 10.38am in order for the Clerk to brief Dr Farry.

The meeting resumed at 10.42am with Dr Farry in the Chair.

The meeting moved into public session at 10.42am.

Members noted the composition of the Committee and the Chairperson introduced the other Committee Office staff.

The Chairperson advised Members that previous Ad Hoc Committees had allowed deputies to stand in where Members could not attend.

Agreed: It was agreed that that nominated Members should try their best to attend meetings to ensure continuity, especially given the Committee’s very tight timescale, but that deputies could attend in their place.

3. Declaration of Interests

The Chairperson reminded Members that the Guide to the Rules Relating to the Conduct of Members requires that, before the first meeting of a Committee, Members must send to the Committee Clerk details of any interests, financial or otherwise, for circulation to the Committee.

The Chairperson invited Members to declare any interests and to forward their Declaration of Interests in writing to the Committee Clerk.

4. Forward work programme

The Clerk gave a brief outline of the current NIO position in terms of consultation on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007 and the Committee’s role in this. The Clerk also advised that Assembly Research staff had been asked to provide a briefing paper for Members on the provisions of the Draft Order.

Agreed: It was agreed that Research staff should give an oral briefing on their paper at the next meeting.

Agreed: It was agreed that Minister Paul Goggins MP and/or NIO officials should be invited to brief the Committee at its next meeting on the provisions of the Draft Order.

Agreed: It was agreed that the NIO consultation list should be obtained and to consider at the next meeting which organisations should be invited to give oral evidence.

5. Draft Public Notice

Agreed: The Committee agreed a public notice to be placed in the local press seeking written submissions on the proposed legislation.

6. Any other business

None.

7. Date, time and place of next meeting

The next meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007 will be held on Friday, 14 December 2007 at 10.30am in Parliament Buildings. The venue would be advised.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11.00am.

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Temporary Chairperson

Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

14 December 2007

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Friday, 14 December 2007

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA

Ms Sue Ramsey MLA

Mr Alastair Ross MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mr Denis Arnold (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Neil Currie (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Roger Kernaghan (Clerical Officer)

Ms Fiona O’Connell – Assembly Research & Library Services (item 5 only)

Apologies: Mr Mickey Brady MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mrs Dolores Kelly MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr John McCallister MLA

Mrs Iris Robinson MP MLA

The meeting opened at 10.35am in closed session with the temporary Chairperson, Dr Farry, in the Chair.

1. Apologies

Apologies are detailed above.

2. Election of Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson

The temporary Chairperson called for nominations for the position of Committee Chairperson. Mr Wells proposed Dr Farry. Mr Ross seconded this proposal and Dr Farry accepted the nomination.

There being no further nominations, the temporary Chairperson put the question without debate.

Question put and agreed:

That Dr Farry, being the only candidate proposed, be Chairperson of this Committee.

Agreed: It was agreed to defer the election of a Deputy Chairperson to the next meeting.

The meeting moved into public session at 10.39am.

3. Draft minutes of the meeting held on 6 December 2007

Agreed: The draft minutes were agreed.

4. Declaration of Interests

The Chairperson reminded Members of the need to declare any relevant interests.

The Chairperson invited Members attending their first meeting to declare any interests, and requested that any Members who had not done so, to forward their Declaration of Interests in writing to the Committee Clerk.

5. Briefing by Assembly Research

Ms Fiona O’Connell from Assembly Research and Library Services briefed the Committee and answered Members queries on the research papers prepared in relation to the provisions of the Draft Order.

The Chairperson thanked Ms O’Connell for the informative briefing.

6. Briefing by Northern Ireland Office on the Draft Order

The following officials from the Northern Ireland Office joined the meeting at 11.08am:

Gareth Johnston – Head of Criminal Justice Reform and Delivery Division

Amanda Patterson – Head of Sexual Crime Unit

Jim Strain – Legal Adviser

Stephen Cowan – Criminal Justice Directorate

The officials briefed the Committee on the purpose and main provisions of the proposed Draft Order. This was followed by a question and answer session.

The officials agreed to provide the Committee with some additional information in relation to the proposed legislation.

The Chairperson thanked the officials for the briefing.

The officials left the meeting at 12.28pm.

7. Forward Work Programme

The Committee discussed which organisations should be invited to give oral evidence to the Committee.

Agreed: It was agreed that the following organisations should be invited to give oral evidence:

- The Christian Institute

- NSPCC

- Barnardos

Agreed: It was agreed that the Chairperson could invite other organisations to give oral evidence, depending on the written submissions received.

8. Any other business

None.

9. Date, time and place of future meetings

The next meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007 will be held on Tuesday, 8 January 2008 at 10.00am in Room 144, Parliament Buildings.

A further meeting will be held on Monday, 14 January 2008 at 9.30am in the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12.37pm.

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Chairperson, Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

8 January 2008

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Tuesday, 8 January 2008

Room 144, Parliament Buildings

Present: Dr Stephen Farry MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mrs Dolores Kelly MLA

Mr John McCallister MLA

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA

Ms Sue Ramsey MLA

Mr Alastair Ross MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mr Denis Arnold (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Neil Currie (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Roger Kernaghan (Clerical Officer)

Mr David Irvine (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mrs Iris Robinson MP MLA

The meeting opened at 10.03am in closed session.

1. Apologies

Apologies are detailed above.

2. Election of Deputy Chairperson

The Chairperson called for nominations for the position of Deputy Chairperson. Mr Ross proposed Mr Wells. Mrs Kelly seconded this proposal and Mr Wells accepted the nomination.

There being no further nominations, the Chairperson put the question without debate.

Question put and agreed:

That Mr Wells, being the only candidate proposed, be Deputy Chairperson of this Committee.

The meeting moved into public session at 10.05am.

3. Draft minutes of the meeting held on 14 December 2007

Agreed: The draft minutes were agreed.

4. Declaration of Interests

The Chairperson invited Members attending the Committee for the first time to declare any interests, and requested that any Members who had not done so, to forward their Declaration of Interests in writing to the Committee Clerk.

5. Oral evidence from the NSPCC

The following representatives from the NSPCC joined the meeting at 10.08am:

Martin Crummey – Director

Avery Bowser – Assistant Director

Colin Reid – Policy and Public Affairs Manager

The representatives gave their views on the proposed legislation. This was followed by a question and answer session.

Mr McCallister joined the meeting at 10.48am.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for the briefing.

The representatives left the meeting at 10.50am.

6. Oral evidence from Barnardos

The following representatives from Barnardos joined the meeting at 10.50am:

Margaret Kelly – Assistant Director

Jacqui Montgomery-Devlin – Children’s Services Manager

The representatives gave their views on the proposed legislation. This was followed by a question and answer session.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for the briefing.

The representatives left the meeting at 11.20am.

7. Forward Work Programme

Agreed: It was agreed that officials from the Northern Ireland Office should attend the meeting on 14 January 2008, in order to respond to the views expressed by Members and interest groups who had given evidence to the Committee. It was also agreed that the submission from the Christian Institute should be copied to the NIO.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the motion to be submitted to the Business Committee to allow for the Committee report to be debated in plenary.

8. Any other business

None.

9. Date, time and place of next meeting

The next meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007 will be held on Monday, 14 January 2008 at 9.30am in the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11.25am.

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Chairperson, Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

14 January 2008

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Monday, 14 January 2008

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Dr Stephen Farry MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Jim Wells MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr John McCallister MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA

Ms Sue Ramsey MLA

Mr Alastair Ross MLA

In Attendance: Mr Denis Arnold (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Neil Currie (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Ms Karen Roy (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr David Irvine (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mrs Dolores Kelly MLA

Mrs Iris Robinson MP MLA

The meeting opened at 9.37am in public session.

1. Apologies

Apologies are detailed above.

2. Draft minutes of the meeting held on 8 January 2008

Agreed: The draft minutes were agreed.

3. Oral evidence from The Christian Institute

The following representatives from The Christian Institute joined the meeting at 9.41am:

Callum Webster – Northern Ireland Officer

Matthew Jess – Research Assistant

The representatives gave their views on the proposed legislation. This was followed by a question and answer session.

Mr McCallister joined the meeting at 9.44am.

Mr Brady joined the meeting at 9.50am.

Rev Dr Coulter joined the meeting at 10.01am.

Mr Wells declared the following interest – he subscribes to The Christian Institute and was one of those who wrote to the Northern Ireland Office in support of the views of The Christian Institute.

The Chairperson thanked the representatives for the briefing.

The representatives left the meeting at 10.21am.

The meeting moved into closed session at 10.21am.

The Committee discussed some of the provisions in the draft Order.

The meeting was suspended at 10.45am.

Mr O’Loan left the meeting at 10.45am.

The meeting reconvened at 11.16am in public session.

4. Oral evidence from Minister Paul Goggins MP

Minister of State Paul Goggins MP joined the meeting at 11.16am, accompanied by the following officials from the Northern Ireland Office:

Gareth Johnston - Head of Criminal Justice Reform and Delivery Division

Amanda Patterson - Head of Sexual Crime Unit

The Minister briefed the Committee on the purpose and main provisions of the draft Order, and responded to the views expressed by Members and interest groups at earlier evidence sessions. This was followed by a question and answer session.

The Chairperson thanked the Minister and officials for the briefing.

The Minister and officials left the meeting at 12.01pm.

Mr Wells left the meeting at 12.01pm.

5. Forward Work Programme

Agreed: It was agreed that the Committee would meet to consider the draft report on Monday, 21 January 2008 at 9.30am. If necessary, a further meeting to sign off on the final report will be held on Wednesday, 23 January 2008 at 9.00am.

6. Any other business

None.

7. Date, time and place of next meeting

The next meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007 will be held on Monday, 21 January 2008 at 9.30am in Room 135, Parliament Buildings.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12.03pm.

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Chairperson, Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

21 January 2008

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Monday, 21 January 2008

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Dr Stephen Farry MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Jim Wells MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Mickey Brady MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mrs Dolores Kelly MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA

Mrs Iris Robinson MP MLA

Mr Alastair Ross MLA

In Attendance: Mr Denis Arnold (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Neil Currie (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr David Irvine (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr John McCallister MLA

Ms Sue Ramsey MLA

The meeting opened at 9.47am in closed session.

1. Apologies

Apologies are detailed above.

2. Draft minutes of the meeting held on 14 January 2008

Agreed: The draft minutes were agreed.

3. Consideration of Draft Report

The Committee considered the draft Report on the Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007, paragraph by paragraph.

Mr Brady joined the meeting at 10.16am.

The meeting was suspended at 10.18am.

The meeting reconvened at 11.02am.

Mr Wells proposed that the Committee strongly recommends that there be no change to the current age of consent at 17. Mr Ross seconded the proposal.

The Committee divided on the proposal. The following Members voted for the proposal:

Rev Dr Coulter, Mrs Kelly, Mr O’Loan, Mr Ross, Mr Wells.

The following Members voted against the proposal:

Mr Brady, Dr Farry, Ms McCann.

The proposal was, therefore, agreed by simple majority.

The Committee agreed the main body of the report as follows:

Paragraphs 1.1 to 1.3 - Agreed

Paragraph 1.4 - Agreed as amended

Paragraphs 1.5 to 1.14 - Agreed

Paragraphs 2.1 to 2.12 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.1 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.2 - Agreed as amended

Paragraph 3.3 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.4 - Agreed as amended

Paragraphs 3.5 to 3.6 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.7 - Agreed as amended

Paragraph 3.8 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.9 - Agreed as amended

Paragraphs 3.10 to 3.13 - Agreed

Paragraph 3.14 - Agreed as amended

Paragraphs 3.15 to 3.24 - Agreed

List of Recommendations - Agreed as amended

The Committee agreed that it was content for the Chairperson to approve the minutes of the meeting of 21 January 2008, to facilitate their inclusion in the report.

Mrs Robinson joined the meeting at 11.10am.

The Committee ordered the Report on the Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 (15/07/08R) to be printed.

4. Any other business

None.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11.14am.

Dr Stephen Farry MLA

Chairperson, Ad Hoc Committee on the Draft Sexual Offences (NI) Order 2007

21 January 2008

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

Page No.

Initial evidence from the NIO on 14 December 2007 29

Evidence from the NSPCC on 8 January 2008 43

Evidence from Barnardo’s on 8 January 2008 50

Evidence from The Christian Institute on 14 January 2008 55

Evidence from Minister Paul Goggins MP and NIO officials on 14 January 2008 61

14 December 2007

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Dr Stephen Farry (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan

Ms Sue Ramsey

Mr Alastair Ross

Mr Jim Wells

Witnesses:

Mr Stephen Cowan |

Northern Ireland Office |

1. The Chairperson: I welcome the Northern Ireland Office delegation to the Committee. It includes: Mr Gareth Johnston, Head of the Criminal Justice Reform and Delivery Division; Ms Amanda Patterson, Head of the Sexual Crime Unit, Mr Jim Strain, legal advisor, and Mr Stephen Cowan from the Criminal Justice Directorate.

2. Mr Gareth Johnston (Northern Ireland Office): I thank the Committee for the opportunity to give this briefing. I reiterate that Paul Goggins has sent his apologies. He is sorry that he is unable to attend because of diary commitments. However, he stands ready to give the Committee any additional assistance.

3. I propose to say something about the background to the draft Order, and how we have got to this stage. I will say something about the consultation and its results on the proposals that are now in the draft Order. Then I will hand over to Amanda Patterson, who will take the Committee through the detail of the Order. I realise that we will be covering much the same ground as your researcher, but this is an opportunity to put a little light and shade on the proposals.

4. The Chairperson: Will you reflect on some of the comments that have been made so far and try to address those as you go through your presentation?

5. Mr Johnston: Yes. If members have any other thoughts or questions, we will be happy to address them. If we take questions at the end of the presentation, we will have an opportunity to brief members on all of the Order.

6. The review of the criminal law on sex offences in Northern Ireland was originally informed by a Home Office review that was a fundamental look at sexual offences in England and Wales and took over 16 months to complete. The report was entitled ‘Setting the Boundaries’ and it reported to the Home Secretary in April 2000.

7. As a result of the report, in January 2003 the Home Office introduced into Parliament the Sexual Offences Bill, which provided a whole new body of law on sexual offences. The Bill also reformed the sex-offender provisions by strengthening the notification requirements for convicted sex offenders. It received Royal Assent in November 2003, and the Sexual Offences Act 2003 was implemented in May 2004.

8. It was important for us to implement some of the reforms immediately in Northern Ireland. The Act extended to Northern Ireland the reforms around notification requirements and civil preventative orders, such as sexual offences prevention orders, so that the same provision to do with sex-offender notification and the orders that might affect sex offenders were applied in Northern Ireland at the same time. It was, therefore, also necessary to extend some offences to Northern Ireland, particularly those that were necessary to ensure that sex-offender provision operated on a par with the rest of the UK. We implemented the new offences of meeting a child following sexual grooming and paying for the sexual services of a child.

9. It was necessary to address certain issues immediately. We carried out a broader review of sexual offences law in Northern Ireland to deal with the remaining issues. That review was announced in October 2004, and it contained three objectives: Those were: first, to provide coherent and clear sex offences that protected individuals, especially children and the vulnerable, from abuse and exploitation; secondly, to enable offenders, particular those who are abusive, to be appropriately punished; thirdly, to be fair and non-discriminatory, in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Human Rights Act and the Northern Ireland Act 1998. Your researcher stated some of the ways in which the law is amended to be non-discriminatory.

10. We did not want to reinvent the wheel, and we did not seek to repeat all the work that was carried out in the review in England and Wales. We took the position that, unless there was sufficient justification, the law in Northern Ireland should, as far as possible, match that in England and Wales, given that we are talking about what is and what is not a criminal offence. However, we wanted to ensure that people in Northern Ireland were fully consulted.

11. During the review, in October 2003, we wrote to a range of organisations with an interest in, and concerns about, the law on sex offences. We held a consultation seminar in November 2003, to which the same organisations were invited. That helped to inform our thinking on the proposals that are now before the Committee. In July 2006, we published a wider consultation document on reforming the law on sexual offences in Northern Ireland. We received responses to that consultation, which I will come to in a moment, and, in June 2007, we published the summary of those responses.

12. That consultation document, which I believe was presented to the Committee, considered all the offences in the English legislation — the Sexual Offences Act (2003) — regardless of whether they were already law here, and views were invited on whether they should be included in Northern Ireland law.

13. The Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 was published on 20 November and made available to the Assembly for consideration. The Minister was pleased to have the opportunity to give an informal briefing to several members on 26 November.

14. The Order concerns the sexual offences themselves. From listening to the Committee’s deliberations earlier I know that there are questions about victims and sentencing, and those are, clearly, important issues. However, the wider issues were not intended to be part of the present Order, which is simply about defining the law that applies to sexual offences in Northern Ireland.

15. Notification that the consultation document was available was sent to 370 interested organisations, stakeholders and individuals, and we received a total of 64 individual responses. A list of those who responded has been made available to members.

16. Alongside those individually crafted responses a lobby campaign was instituted by the Christian Institute and, as a result of that, we received over 4,000 emails and letters supporting its views on four issues arising from the consultation document. Those four issues were: changes to the age of consent; criminal law and under-age sexual activity; the offence of sex in public toilets; and the definition of a brothel.

17. There was very broad support from the majority of respondents for reforming the law on sexual offences in Northern Ireland to bring it along similar lines to England and Wales. The greatest divergence of views was in relation to children, and some of your researcher’s questioning concerned the law for children of 13, then 14- to17-year-olds. The majority agreed that all sexual activity with children under the age of 13 should be illegal, and that rape and assault offences should be formulated without the need for lack of consent to be proved, and that is what we have done — if the child is under 13 the offence will automatically be considered to have been without consent. We take the view that children of that age are not in a position to give informed consent.

18. The majority of respondents who commented directly — 24 out of 39 — agreed that the age at which young people can have their consent to sexual activity recognised by the law should be equalised with the rest of the UK. I refer to the individually crafted responses, rather than those expressing the Christian Institute’s concerns.

19. Those respondents, who were in agreement with equalising the age, included organisations, such as the NSPCC and Barnardo’s, who regarded it as important in ensuring that young people will feel free to avail of support services and advice on sexual relationships. There is a view amongst professionals that 17-year-olds are discouraged by the present law from seeking help and advice about sexual offences, and that, if those services were readily accessible and available to that age group, our rate of teenage pregnancy might be reduced.

20. The one issue on which there was not consensus was on how to deal with consensual sexual activity between children. There are several potential models. There had been a suggestion about providing an age-differential approach to the criminalisation of activity between children, but that did not receive sufficient support to make it a viable option.

21. In light of that lack of clear consensus, we have taken the view that it is best — as I said earlier — to keep the law in Northern Ireland as close as possible to that of England and Wales. Moreover, it confirmed the Minister’s position that, unless there was sufficient evidence and justification for deviating from the Sexual Offences Act 2003, we should adopt the same position in the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007. That is what has happened regarding to sexual activity between children. Amanda will say more about that later.

22. Ms Amanda Patterson (Northern Ireland Office): I apologise in advance if I cover some of the same ground that the researcher has gone over.

23. Before I go through the separate parts of the Order, I want to make several points about the context, and that will give some understanding as to how it all fits together. First, as the Committee has heard, it is based on Part 1 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003. We consulted on the basis that there would be change only if sufficient evidence was submitted to justify a difference for Northern Ireland. From the consultation document and the responses, we did not get that consensus of evidence.

24. All of the existing law on sexual offences in Northern Ireland was on the table for review. All of that law will be replaced by the offences in the new Order. That represents, not simply a consolidation, but a fundamental reform of the law in Northern Ireland, which is the only time that that has happened. We still deal with statutes that date back to the end of the nineteenth century.

25. As has already been said, the policy consultation was not a root-and-branch review for Northern Ireland — we did not want to reinvent the wheel — and we used the stringent and fundamental review that informed the Sexual Offences Act 2003. Therefore, the Order will replace virtually all of the current sexual offences in Northern Ireland and will provide a new framework of offences for the twenty-first century. All offences will be couched in a gender-neutral context.

26. Approximately 40% of the content of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 — some 19 offences — already extend to Northern Ireland. Those include the grooming offence; the abuse of trust offences; the abuse of children through prostitution and pornography; the exploitation of prostitution; the trafficking offences; exposure; voyeurism; sex with animals; sexual penetration of a corpse; and sex in toilets. All of those offences have been part of the law in Northern Ireland since 2004.

27. The three trafficking provisions have already been the subject of some discussion and are remaining in law in Northern Ireland as part of the Sexual Offences Act 2003. That is because those provisions are UK wide; they relate to trafficking into and out of the UK and therefore it is sensible for them to stay in the Sexual Offences Act 2003. The remainder of the offences now make up the proposed draft Order, comprising a total of 52 offences.

28. Therefore, 36 new offences from the Sexual Offences Act 2003 are being incorporated into this Order. The new offences are rape; assault by penetration; sexual assault; causing a person to engage in sexual activity without consent; those same offences regarding children under the age of 13; all of the offences against children under the age of 16; the familial child sex offences against children under the age of 18; the offences against persons with a mental disorder; the preparatory offences where the intent is to commit a sexual offence; and sex with an adult relative. Those are all offences that are law in England and Wales but not in Northern Ireland.

29. For interest, the Committee may like to know that those replace the current offences, which are the common law offence of rape; indecent assault; unlawful carnal knowledge of both someone under the age of 14 and someone under the age of 17; buggery; indecent conduct towards a child; prostitution of a child; all the old procuration offences; offences against women with mental-health problems — not men — and against mental-health patients; incense — sorry, I mean incest —[Interruption.]

30. Mr Wells: The Roman Catholic Church will be delighted about that.

31. Ms Patterson: The others are loitering and importuning for prostitution; bestiality; and many other lesser-used offences that I will not go into now.

32. That makes up the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007. The only offences additional to those of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 are the prostitution offences, kerb-crawling, and soliciting for prostitution.

33. The draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 is presented in several parts. Part 1 offers an introduction, and interpretation of, the draft Order. Part 2 deals with non-consensual sexual offences. Part 3 deals with sexual offences against children, and is sub-divided into offences against children under the ages of 13, 16 and 18.

34. Part 4 of the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 deals with sexual offences against persons with a mental disorder. Part 5 deals with prostitution and exploitation. Part 6 deals with miscellaneous sexual offences.

35. It is useful to know that only Part 2 deals with non-consensual offences. The remainder of the draft Order describes unlawful behaviour that is not dependent on proof that consent was absent. A large amount of the draft Order is designed to target abusive and exploitative behaviour against vulnerable groups.

36. I shall outline the parts of the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 in some detail, and try, briefly, to describe the major changes.

37. Part 1 is the introductory part of the Order. The major new legislation is the definition of consent, which will now be available to the courts. Consent is whereby a person agrees by choice, and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice.

38. Part 2 deals with the non-consensual offences, whereby lack of consent makes the behaviour criminal. That behaviour would not be criminal if there was not a lack of consent. Changes to the offence of rape will now include oral penetration, and will remove the defence whereby a person could avoid conviction for rape if he had an honest, but mistaken, belief in consent. The difference between the draft legislation and the current legislation is that that belief will now have to be “reasonable”.

39. Assault by penetration is a new offence that attracts the same penalty as that for rape. Therefore, that offence is considered to be as serious as that of rape. It provides, specifically, for serious assaults that involve penetration by something other than a penis. Currently, someone who has committed such as offence would be charged with the offence of indecent assault, for which the maximum sentence is 10 years imprisonment. Under the proposed legislation, that offence would attract a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. That demonstrates the seriousness of that type of behaviour.

40. Sexual assault is another new offence, which is a direct replacement for the offence of indecent assault. It attracts a maximum penalty of 10 years imprisonment. Causing sexual activity without consent is a further, new and serious offence. It attracts a maximum penalty of life imprisonment for penetrative acts and 10 years for other acts, which is a means of including other circumstances whereby the offender makes someone else perform a sexual act himself or herself, or with a third party.

41. The evidential presumptions, which can be applied to the issue of consent, are included in Part 2. If circumstances from a particular list are present, the court can presume that consent was not given — unless the defendant can offer evidence to the contrary. A narrow list of conclusive presumptions is also included in Part 2. Again, it is a list of circumstances that, if present, the court can presume that consent is absent. In that case, the defendant cannot raise the issue at all.

42. Part 3 of the draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 provides for sexual offences against children. It differs from the current Sexual Offences Act 2003 because it attempts to provide a better explanation of how the offences against children work. First, as your researcher has explained, there are offences against children under 13 years of age that are the same as the generic, non-consensual offences — except, that consent will not be raised as an issue. There is no need to establish that consent was absent.

43. Those offences replace the current offence of unlawful carnal knowledge with a girl under the age of 14. That is very important, because the current offence is simply for sexual intercourse with a girl under the age of 14. All other sexual activity with children is currently dealt with by the offences of indecent assault or indecent conduct towards a child, with a maximum sentence of 10 years. As things stand, the penetrative offences would now warrant a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, and other conduct would attract a maximum sentence of 14 years. That represents a substantial increase of the sentences for those offences.

44. The second tranche of offences against children are the sexual offences that apply for all children under the age of 16. Those are new offences, which mean that all sexual activity with a child under 16 years of age is offending behaviour. That behaviour is repeated in various circumstances throughout the draft Order. It is broken down into sexual activity with a child; causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity; engaging in sexual activity in the presence of a child; and causing a child to watch a sexual act. Those are all specific offences designed to make it easier to make a charge stick.

45. Currently, all of those behaviours fall within the offences of unlawful carnal knowledge of a girl under the age of 17, indecent assault, or indecent conduct. There is a big difference, because the maximum sentence for unlawful carnal knowledge of a girl under the age of 17 or indecent assault of a girl under the age of 17 is two years. Indecent conduct towards a child attracts a maximum sentence of 10 years. The new offences increase that maximum penalty to 14 years, and that is a substantial difference. Moreover, that list of offences includes arranging or facilitating the commission of a sex offence. I heard the question that was asked of the researcher, but I cannot answer it at the moment. I will be happy to provide the Committee Clerk with a response, if that is acceptable. The offence of meeting a child following sexual grooming is already in place in that same part of the legislation for Northern Ireland.

46. The next section of that Part of the legislation concerns offences against children under 18 years of age. The offences concerning the abuse of a position of trust are already in the law in Northern Ireland. They involve the type of offending behaviour that I have just described, but they apply to situations in which there is exploitation of a position of trust with a child. Those might include children in a care home, in health care, in an educational institution, in a children’s home, or detained by order of the court in a young offenders’ centre. It is against the law to have any sexual activity with anyone under the age of 18 wherever a position of trust is established. That is an important point: those penalties apply to offences committed against anyone under the age of 18. There are exceptions in these sections and in the next particular section for spouses and civil partners, and for relationships which predated the formation of the position of trust.

47. The next section in that Part of the legislation deals with familial sex offences against children under 18. Those are new offences, which make it an offence to have any sexual activity with a family member under the age of 18, and have been expanded to include all relationships in which care is provided by someone living in the same household. That takes into account all sorts of extended family relationships, partners, foster parents, step-parents, to try to cover comprehensively offences in the home situation.

48. Offences related to preventing exploitation of children up to the age of 18 from abuse through prostitution and pornography abuse are already established in law in Northern Ireland.

49. Sexual offences against a person with a mental disorder are new offences for Northern Ireland. Such people are the other major group of vulnerable people that the Order targets with special protection. Currently, the Mental Health Order 1986 provides for offences against women with a mental disorder, or against patients in hospitals. The maximum sentence for offences in both of those categories is two years. At present, offences against people with a mental disorder are covered by broad offences, such as indecent assault, which require the court to address the issue of consent.

50. The new offences outlaw any sexual activity with a person who lacks the capacity to choose. It makes it criminal behaviour to use inducement to obtain sex with someone with a mental disorder. Similarly, it bans care workers from sexual activity with anyone in their care who has a mental disorder. With regard to people in a position of trust, for example care workers, it provides the same level of protection for people with a mental disorder as it does for people who are under 18.

51. The next Part is new, and deals with offences not covered by the Sexual Offences Act. This section on prostitution includes the new offences of soliciting and kerb-crawling, which have been included in the Order as a direct result of public concerns and a police request for legislation to deal more effectively with issues surrounding prostitution and public nuisance in one area of Belfast. It also re-enacts offences relating to the exploitation of prostitution, which were already law in Northern Ireland and have not changed.

52. Finally, Part six covers miscellaneous offences. New to Northern Ireland are the preparatory offences that can be charged if an offence has been committed and it can be proved that the intent was to commit a further sexual offence. Some such offences are already covered by Northern Ireland statutes, for example, there is an offence of burglary with intent to rape. However, the new section covers all sorts of criminal behaviour outside that. Intent to commit a sexual offence must be proved.

53. That Part of the Order also introduces the offence of administering a substance with intent to carry out a sexual offence. That is designed to deal with such situations as the use of the so-called date-rape drugs.

54. Also new in that Part are offences of sex with an adult relative. Those replace the current incest offences, which date back to the early part of the last century. All the other offences in that part are already on the statute book for Northern Ireland, such as voyeurism, exposure, sex with animals and so on.

55. That concludes my submission on the Order, and I am grateful to have had the opportunity to present it to the Committee.

56. The Chairperson: Thank you, the floor is now open for questions.

57. Mr Wells: I have a feeling of déjà vu, because you — or some of your staff — appeared before the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister on the issue of transsexuals. During that meeting, someone from your staff — I am not sure who — proposed to bring legislation on transsexuals into line with that for gay people and lesbians. Exactly the same thing happened. You took the observations made by respondents, and you analysed them. Then you took the Christian Institute’s responses, which were much more detailed than anyone else’s, and you said that they were somehow different.

58. I notice that in ‘Reforming the Law on Sexual Offences in Northern Ireland: summary of responses to a consultation paper’ there is a whole analysis of 22 or 23 responses to each subject, at the very end of which there is a throw-away line saying that there were 4,000 responses from the Christian Institute. You have given half of a page — a couple of paragraphs — to the analysis of those responses. Those 4,000 responses are all from Northern Ireland people who have felt it necessary to write to the NIO on that subject. Am I not right in thinking that perhaps you have given less validity to those responses than to the other 22 or 23 responses?

59. Ms Patterson: One observation is that the 4,000 responses were all on the same issue.

60. Mr Wells: There were four specific issues.

61. Ms Patterson: There were four specific issues. The other respondents dealt with a range of issues, and the 4,000 respondents dealt with the document from the Christian Institute that covered those four issues.

62. Mr Wells: People look to their church or youth group on such issues, which, clearly, are of concern to people in Northern Ireland.

63. Ms Patterson: One example concerns sex in a public toilet. The Christian Institute’s lobbying document made the point that the NIO was trying to downgrade the offence of sexual activity in a public toilet; however, that is not the case. The consultation document simply suggested that it might be better to move that offence from one piece of legislation to another, because the offence is where the sexual activity happens, and not the activity itself. The legislation does not reduce the penalty, and it remains in the Draft Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2007. In one respect, the issue has been dealt with in the way in which the Christian Institute wanted. Similarly, the legislation does not change the definition of a brothel; it remains the same.

64. Mr Wells: What about criminal law on underage sexual activity?

65. Ms Patterson: As we said from the word go in the consultation document, the legislation on those issues would be the same as that in England and Wales, unless evidence were provided to the contrary for Northern Ireland. No specific reasons were given to suggest that the Order should be different to the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

66. Mr Wells: Do you accept the principle on, for instance, abortion? The UK Government have decided that that legislation can be in keeping with the ethos of this part of the United Kingdom. For a long time, drink licensing in Northern Ireland has been different to the rest the United Kingdom. Are we in any way bound to follow slavishly the 2003 Act, or can we make decisions that we believe are in keeping with the general view of the Northern Ireland community, which might have a different threshold of acceptance of certain sexual activity?

67. Mr Johnston: The Committee is, of course, able to make any recommendations that it wants. My specific focus must be to consider the evidence around the issues in the draft Order. Perhaps it would be helpful if I were to set out some of the thinking that has led to the issue around the age of consent. As has been observed, it is not that the age of consent is a legal issue that is defined in a clause of the legislation; it comes about because of the phrasing of the offences.

68. First, we are conscious that the legislation concerns the age at which sexual activity is criminalised, not the age at which it is advisable, or at which the Northern Ireland Office would encourage activity. We simply consider the limits of the criminal law and whether there is due justification for having a different standard of criminal law, whereby people in Northern Ireland, as compared with the rest of the United Kingdom, could be prosecuted and sent to prison.

69. Secondly, research indicates that there is little or no correlation between the age of consent in various countries and the levels of teenage sexual activity. In the Netherlands, for example, the age of consent is 16, but it has one of the lowest levels of teenage pregnancy, and there are other international examples. In Northern Ireland, the age of consent is 17 and, alas, there is a significant level of teenage pregnancy. The criminal law in itself does not do much to encourage or discourage young people from having sex.

70. Thirdly, the provisions are clear about strengthening protection for children under 16, particularly those who might be at risk of exploitation from those whom they trust.

71. Finally, I want to put on record that there is already an exception to the age of consent at 17 in Northern Ireland, which is that young people can marry at 16 with their parents’ consent. Sexual activity in such a marriage is not unlawful carnal knowledge. Therefore, there is already a set of situations in which young people of 16 can legally engage in sexual activity.

72. Those considerations, particularly around criminalisation, lie behind the position that is taken in the draft Order.

73. Mr Ross: You mentioned that research on levels of teenage sexual activity shows that there is no correlation between that and the age of consent. What, therefore, correlates to the level of sexual activity in teenagers according to the research? It seems that if the law is liberalised — the age of consent lowered by even a year — it will send out a message to children that the law is reflective of what is already happening. Therefore, if there is a perception that 15- and 16-year-olds are engaged in sexual activity, it will put increased pressure on children to act their age and do the same. There are already other pressures on young people. What does the research suggest?

74. Mr Johnston: The two factors that seem to have most impact on that are first, the prevailing culture — which, I appreciate, is difficult to define — and secondly, good-quality sex education, support and advice. One of the usual measures in countries with lower levels of teenage pregnancy is that there are good sex education arrangements.

75. Ms Patterson: Consultation responses from organisations that deal with children were in favour of the courts having a similar age of consent throughout the United Kingdom. No evidence was put forward or support given for maintaining a higher age of consent than that of England, Wales and Scotland. The age under which it is illegal to have sex in the Republic of Ireland is still 17 years, as it is in Northern Ireland. However, that has been the age of consent in the Republic since 1950 and it is currently being reconsidered. The issue will be addressed within a couple of years.

76. Mr Wells: Surely, the Assembly should try to raise standards in society, rather than bring them down. The NIO’s logic is that if children of 14 years of age are involved in sexual activity, the law must be brought down to the level of current practice; rather, it should send out a clear signal that society does not want that to happen, that it wants to drive standards up, so that there is less sexual activity between unmarried teenagers.

77. Mr Johnston: It is not a lowest-common-denominator decision. It is about examining the evidence that has been presented to the NIO by organisations that work with children.

78. Mr Wells: It was supported by only 24 respondents out of more than 4,000.

79. Mr Johnston: I have commented on the range of responses. The evidence presented by organisations that are directly involved with children raises concerns that the law as it stands discourages young people of 17 years of age from seeking advice and support that might help them to be more responsible about their sexual activity. Those organisations believe that amending the law would be a positive step.

80. Ms S Ramsey: I want to return to that point shortly, Chairperson. The fact is that positive changes have been proposed in the draft legislation. That is to be welcomed, and I do welcome some of it. However, as the NIO is well aware, the Committee’s purpose is to bring forward the Assembly’s response to the consultation document. Therefore, my questions and comments are designed to tease out some of the issues, which will then be brought to the Floor of the House for debate.

81. I note that the matter is separate from sentences, 50% remission or victims. However, it cannot be looked at in isolation. You are involved in criminal justice, and you will take on board what the Committee has said when you return to your team. There is concern surrounding victims and sentencing. You referred to the maximum sentence for a, b, c, d and e, and that is welcome; however, there is an issue about the legal profession’s use of the proposed new law. Furthermore, we are well aware of the issue of 50% remission, and that, too, can be fed into your deliberations.

82. The two previous speakers dealt with consent and young people, and I note that there is a suggestion that you need to consult with young people. Has that happened? An equality impact assessment was referred to in your document. Has there been any movement on that?

83. Taking on board the issue of the sexual activity between young people — and I do not want to get into that discussion — I am concerned that, in some instances, we are dealing with professional predators who look for children under or over 13 years of age and who, at every opportunity, try to stay one or two steps ahead of the law, no matter what changes there may be to the legislation. I am concerned that some professional predators may groom a child and wait until that child is 13 years old. We have seen evidence where a person can sit and wait.

84. Has there been any formal work with the legal profession? We can make the best laws in the world, but there is ample evidence to show that when a predator goes to court, those laws are not enforced. However, there are a many issues in the draft Order that are a positive step forward and are welcome.

85. Mr Johnston: The Order focuses on the sexual offences and the law surrounding sexual offences. The criminal justice directorate is taking forward several initiatives and it has been consulting the Assembly separately on the new draft Criminal Justice Order 2007, which would end automatic 50% remission for all sentenced prisoners. There are particular provisions in the Order for dangerous, violent and sexual offenders, so that extended or indeterminate custodial sentences would be available where risk is assessed, and risk would be a deciding factor in how long such people stayed in prison.

86. The Order also contains much improved arrangements for supervision of offenders in those categories when they are released. We have consulted the Assembly, separately and in a different forum, on those provisions.

87. Ultimately, sentencing is a matter for the courts and, as a member of the Civil Service, I cannot comment on sentencing practices. The draft Criminal Justice Order 2007 will provide a wider and improved range of sentencing options to sentencers, and that is a step forward.

88. Ms S Ramsey: Has the legal profession been formally consulted on any of those proposed changes?

89. Ms Patterson: The guidelines and the implementation will generate most of the consultation on the Order.

90. Mr Johnston: We have regular meetings with the Bar and the Law Society, and we are looking at how we can strengthen the arrangements for those meetings. One of the issues we could raise with professional lawyers is how we can help with training or support as proposals go forward for implementation.

91. Ms Ramsey also mentioned concerns about professional predators and children aged 13. The rape offence is still available in cases where the child is aged 13 or over, and the definition of consent will be helpful in such circumstances, because it is very much a matter of free consent. One could see that, where an individual has groomed a child, it could be put that that was not free consent. Furthermore, sexual activity with a child would still attract a penalty of up to 14 years, even if non-consent could not be proved.

92. Ms S Ramsey: I am well aware of that, but I live in the real world, and my concern is that professional predators can fill the head of a young girl aged 13 or 14 with everything. She might get carried away and say that she has given her consent, but, ultimately, the predator has groomed her.

93. Mr Johnston: Even with consent, a penalty of up to 14 years would be available, which is an extension of the penalties that are currently available.