Session 2007/2008

First Report

AD HOC COMMITTEE ON THE DRAFT CRIMINAL JUSTICE (NI) ORDER 2007

Report on the

Draft Criminal Justice (NI) Order 2007

TOGETHER WITH THE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, MINUTES OF EVIDENCE

AND WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS RELATING TO THE REPORT

Ad Hoc Committee on the

Draft Criminal Justice (NI) Order 2007

The Committee was established by resolution of the Assembly on Monday 19 November 2007 in accordance with Assembly Standing Order 48(7). The remit of the Committee was to consider the proposal for a Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 and to report to the Assembly by 28 January 2008.

The Committee had eleven members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson. Its quorum was five. The membership of the Committee was as follows:

Mr Alban Maginness, Chairperson

Mr Raymond McCartney, Deputy Chairperson

Mr Alex Attwood Mr Alan McFarland

Ms Carál Ní Chuilín Mr John O’Dowd

Dr Stephen Farry Mr Jim Wells

Mr Danny Kennedy Mr Peter Weir

Mr Nelson McCausland

Mr Danny Kennedy - was unable to attend meetings as the dates mostly clashed with meetings of the Committee for OFMDFM which he chairs.

The Report and Proceedings of the Committee are published by the Stationery Office by order of the Committee. All publications of the Committee are posted on the Assembly’s website at http://archive.niassembly.gov.uk

Table of Contents

BACKGROUND TO THE REPORT

Proposed Draft Criminal Justice (NI) Order 2007

Establishment and Remit of the Ad Hoc Committee

Proceedings of the Committee

Acknowledgements

OVERVIEW OF THE PROPOSED DRAFT CRIMINAL JUSTICE

(NORTHERN IRELAND) ORDER 2007

COMMITTEE’S CONSIDERATION OF THE PROPOSED DRAFT

CRIMINAL JUSTICE (NI) ORDER 2007

General Comments

Sentencing and Release on Licence Arrangements

Curfews and Electronic Monitoring

Supervised Activity Orders

Parole Commissioners

Risk Assessment and Management

Probation Service

Prison Service

Lack of an Open Prison Facility

Other Prison Issues

Road Traffic Offences

Alcohol Interlock Ignition Schemes

Seizure of Vehicles Causing Alarm, Distress or Annoyance

Test Purchases of Alcohol

Alcohol Consumption in Designated Public Places

Prison Security and Offences

Live Links

Legal Aid

Changes to the Police and Criminal Evidence (NI) Order 1989

Penalties

Driving Disqualification for any Offence

Proving Execution of Arrest Warrants

Anti-Social Behaviour Orders

Youth Justice

Publicising the Facts and the Changes

Resourcing the Implementation of the Changes

Appendix 1 - Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2 - Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3 - Written Submissions and other Correspondence considered by the Committee

Appendix 4 - List of Witnesses

Background to the Report

Proposed Draft Criminal Justice (NI) Order 2007

1. On 8 November 2007 the Northern Ireland Office published for consultation a proposed Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 and asked for comments on the proposals by 31 January 2008.

2. In accordance with Section 85 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, Mr Paul Goggins MP, on behalf of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, referred the Draft Order to the Assembly for its consideration.

3. Copies of the Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 and the accompanying Explanatory Document issued by the Northern Ireland Office are accessible on the NIO’s website at www.nio.gov.uk

Establishment and Remit of the Ad Hoc Committee

4. On 19 November 2007 the Assembly agreed, in accordance with Assembly Standing Order 48(7), to establish an Ad Hoc Committee with a remit:

to consider the proposed Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 and to submit a report to the Assembly by 28 January 2008.

5. This is a Report made by the Ad Hoc Committee and it describes its work during the period 22 November 2007 to 21 January 2008.

Proceedings of the Committee

6. At the Committee’s first meeting on 22 November 2007, the Committee elected Mr Alban Maginness as temporary Chairperson. The Committee agreed a schedule of further meetings and a list of organisations that should be invited to give oral evidence to the Committee. The Committee also agreed to place a Public Notice in the four main newspapers, inviting written submissions on the proposals from interested parties.

7. At its meeting on 28 November 2007 the Committee elected Mr Alban Maginness as permanent Chairperson and Mr Raymond McCartney as Deputy Chairperson. During this meeting the Committee was given an overview of the Draft Order by officials from the Northern Ireland Office (NIO).

8. At its meeting on 5 December 2007 the Committee was given a background briefing on the draft legislation and the various consultations which had preceded it by Assembly Research staff.

9. The Committee held eight meetings on the following dates: 22 and 28 November 2007; 5, 12 and 18 December 2007; 9, 16 and 21 January 2008. The Minutes of Proceedings for these meetings are included at Appendix 1.

10. In the Course of its proceedings, the Committee took evidence from the following organisations:

- The Northern Ireland Office

- The Department for Social Development

- The Probation Board for Northern Ireland

- Criminal Justice Inspection Northern Ireland

- The Chairperson of the Life Sentence Review Commissioners

- The Department of the Environment

- The Northern Ireland Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders

- The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission

- The Northern Ireland Prison Service

- The Police Service of Northern Ireland

11. A complete list of those representatives who gave evidence to the Committee is included at Appendix 4.

12. The Minutes of Evidence for these meetings are included at Appendix 2.

13. Written Submissions received by the Committee are attached at Appendix 3.

Acknowledgements

14. The Committee would like to express its sincere thanks to the representatives of all the organisations listed above who provided written and oral evidence, in some cases at short notice. That evidence was very beneficial to the Committee’s understanding of the wide range of provisions within the proposed Draft Order and the implications for our criminal justice agencies and our wider society. The Committee would also wish to record its appreciation of the assistance provided by Ms Carol Doherty and Ms Claire Cassidy, Assembly Research and Library Services.

Overview of the Proposed Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007

15. This overview of the proposed Draft Order (the Order) has been adapted from the NIO’s Explanatory Document.

16. A full copy of the Order and the accompanying Explanatory Document can be accessed on the NIO website www.nio.gov.uk

17. The Order is divided into six separate Parts which are outlined below.

Part 1 -Introductory

18. This Part provides for the title, commencement and most interpretation provisions in the Order. In overall terms it allows for different provisions to be commenced at different times and in different ways. Provisions will commence by order of the Secretary of State and some within one month of the Order being approved by Parliament.

Part 2 – Sentencing

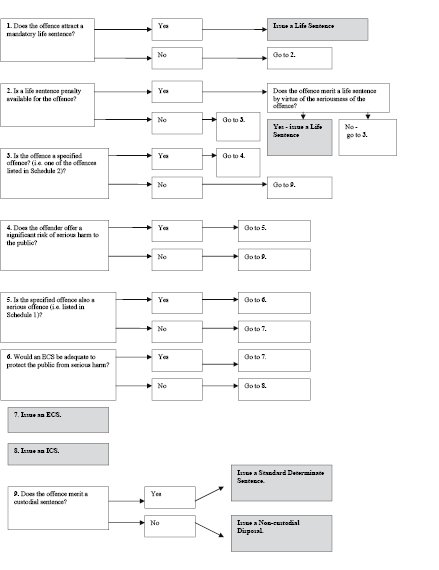

Dangerous Offenders

19. Chapter 1 provides for the introduction of new public protection measures for the sentencing and assessment of dangerous violent and sexual offenders. Dangerousness is assessed as whether there is a significant risk of serious harm to members of the public by the commission of further such offences. Serious harm means death or serious personal injury whether physical or psychological.

20. If an offender has been assessed as dangerous and has been convicted of a specified and serious sexual or violent offence with a maximum penalty of 10 years or more, he will receive either a discretionary life sentence, an indeterminate custodial sentence (an “ICS”), or an extended custodial sentence (an “ECS”). The offender would only receive an ICS if the court considers that an extended sentence would not be adequate to protect the public from serious harm and will specify a minimum term or “tariff” which the offender is required to serve in custody. Unless revoked, the licence remains in place for life. The “tariff” must be at least two years.

21. A dangerous offender who has been convicted of a specified sexual or violent offence for which the maximum penalty is less than 10 years will be given an ECS. This sentence will be a determinate sentence of at least one year and offenders will become eligible for release at the half way point. In addition to the custodial part, courts will set extended supervision periods of up to five years for violent offenders and eight years for sexual offenders.

22. When considering these public protection sentences, dangerousness will be assessed by the court. Dangerousness assessments will be based on reports specifically prepared for that purpose by specialists including probation officers, psychiatrists or psychologists.

23. New arrangements are created for prison sentences and for prisoners’ release on licence; recall to prison following breach of licence requirements; and further re-release.

24. Release from the public protection sentences will involve a new independent body of Parole Commissioners for Northern Ireland. On completion of the ICS tariff, the offender is risk assessed by the Parole Commissioners. The prisoner can be released or required to remain in prison until the risk has sufficiently diminished to allow release and supervision in the community. For an ECS, release would be possible during the second half of the sentence based on the Parole Commissioners’ risk assessment. If not released at that point, the person must be released at the end of the custodial part.

25. Following release, all public protection prisoners will be on licence and under supervision. During their licence period – for the ICS sentence that could be in place for life; for the ECS that could be up to 8 years – prisoners may be recalled to custody by the Secretary of State for breach of conditions. Any recalls will be reviewed by the Parole Commissioners.

Custodial Sentences

26. Chapter 2 contains general provisions on custodial sentences. These include restrictions on imposing discretionary custodial sentences, appropriate lengths of custodial sentences, splitting discretionary custodial sentences into custody and licence parts, and procedural requirements for imposing discretionary custodial sentences. Provisions are also made for additional requirements in the case of mentally disordered offenders and for the disclosure of pre-sentence reports. For the purposes of legislative consolidation, Chapter 2 replicates some provisions from the Criminal Justice (NI) Order 1996.

Release on Licence

27. Chapter 3 creates revised arrangements for prisoners’ release on licence; recall to prison following breach of licence requirements; and further re-release. Offenders serving standard determinate sentences will be released on licence at a point determined by the court. For prison sentences of less than 12 months, the court will set licence conditions; for longer sentences (those of 12 months or more), the Secretary of State will set licence conditions taking into consideration the court’s recommendations. On release, offenders sentenced to custody will be placed under supervision. This new form of imprisonment will replace unconditional release at the halfway point and will remove automatic 50% remission.

Curfews and Electronic Monitoring

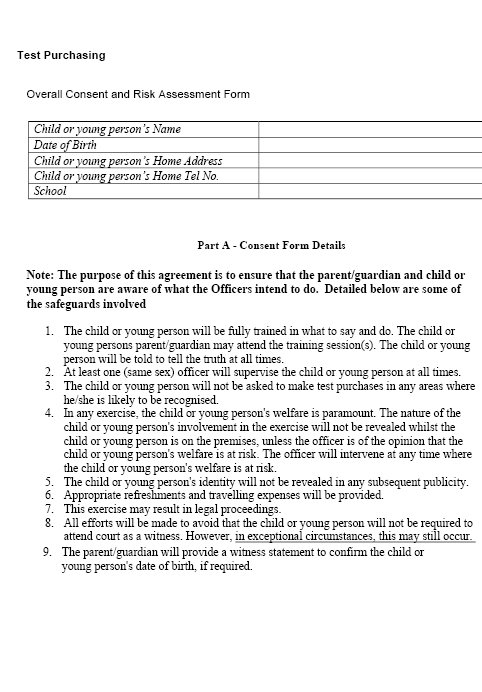

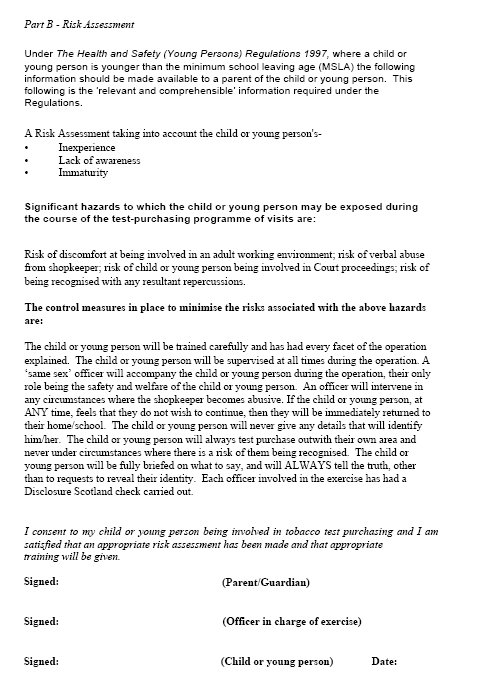

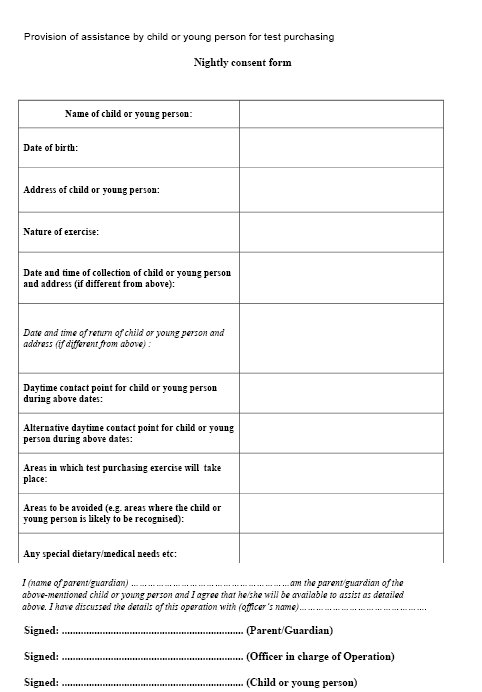

28. New powers will allow increased use of curfews as a condition of bail; as a condition or requirement attached to certain non-custodial sentences; and as a condition of a licence on release from custody. The parallel creation of powers for electronic monitoring or ‘tagging’ will allow also the effective monitoring of curfews and, therefore, their wider use in preference to custodial sentences or remands in custody.

29. The proposals also provide the Secretary of State with a power to release early a standard determinate prisoner subject to curfew and electronic monitoring requirements. Any such release will be subject to strict conditions and can only occur towards the end of the sentence. Such release could be used to facilitate re-integration into the community and to reduce the risk of re-offending.

Supervised Activity Orders

30. Chapter 5 and Schedule 3 create a Supervised Activity Order available to the court as an alternative to custody for fine default. Rather than being sent to prison for non-payment of a fine, courts will be able to impose a community-based alternative.

31. The Supervised Activity Order will be available for fines up to £500 and will have a minimum of 10 hours and maximum of 100 hours activity requirement. Activities will be set and supervised by a supervising probation officer. Failure to comply can result in a longer prison sentence than would have been the case had a custodial period been set in the first instance.

Parole Commissioners

32. Chapter 6 and Schedules 4 and 5 create a body of independent Parole Commissioners for Northern Ireland to assess dangerous offenders’ suitability for release into the community and to review decisions recalling prisoners on licence to custody. The current Life Sentence Review Commissioners are renamed and their role extended to include these functions. The Parole Commissioners provisions largely replicate and replace those already in law by way of the Life Sentences (NI) Order 2001.

Part 3 -Risk Assessment and Management

33. Part 3 creates a duty on a number of criminal justice agencies and other organisations to more effectively assess and manage the risk posed by certain persons in the community, where that risk can best be managed by agencies sharing information and working together.

34. The agencies that will be operating the arrangements are specified and include the police, the prison service, probation service, the NSPCC, and relevant Government Departments or agencies.

35. The powers do not give any additional statutory powers to individual agencies but seek to maximise the effectiveness of their existing statutory functions through multi-agency working. Guidance, prepared by the agencies and approved by the Secretary of State, will provide the detail of how the arrangements will operate in practice. An annual report must be prepared.

Part 4 – Road Traffic Offences

36. Part 4 of the Order contains new powers to address areas of road traffic law. The provisions cover : “Bad driving” including a new definition of “careless driving”; a new offence of “causing death or grievous bodily injury by careless driving”; and more severe penalties for unlicensed, disqualified or uninsured drivers who cause death by driving; “Drink driving” including tighter laws on failing to allow specimens to be tested; stronger police powers to obtain breath specimens; and regulations regarding ‘alcohol ignition interlock’ programmes. Also included is a series of police powers to seize vehicles causing alarm, distress or annoyance (mini-scooters or quads being raced around public streets); and to regulate the use of devices used by some motorists to avoid speed detection.

Part 5 – Miscellaneous and Supplementary

Purchase and Consumption of Alcohol

37. Part 5 makes provision for combating alcohol-related nuisance and disorder and addresses the problem of the sale of alcohol to minors. A “test purchase” power is to be created to allow police officers to identify bars and off-licences selling alcohol to under 18s. The test purchase power can only be used under the direction of a police constable; with written parental consent; and with a requirement to avoid any risk to the welfare of the minor.

38. Powers are also created to deal with the consumption or possession of alcohol in designated public places where there is a problem of anti-social behaviour associated with drinking alcohol. An offence would be committed when a person failed to comply with a constable’s request not to drink alcohol, or with his request to surrender alcohol. Public places would be designated by District Councils. The maximum penalty on conviction of the new offence would be a fine of up to £500. A fixed penalty (set initially at £50) would be available as an alternative to prosecution.

Prisons

39. A number of amendments are proposed to the Prison Act (Northern Ireland) 1953, including minor miscellaneous changes concerning medical officers and amendments to better control, regulate and modernise prison security. Amendments to the laws on assisting a prisoner to escape and conveyance of prohibited articles into or out of prison including drugs, weapons, mobile phones, satellite phones and cameras are also provided, with increased penalties.

Live Links

40. A number of provisions are included to consolidate the law on and increase the use of live video links. Such facilities are already in use for prison remand purposes and have the benefit of providing a cost-effective and secure means for prisoners to participate in remand hearings without having to be transported to court. The new powers will expand the use of video links in Courts to include, in certain circumstances: preliminary hearings, sentencing hearings, evidence of vulnerable accused, and appeals under the Criminal Appeal Act.

Legal Aid

41. Two technical amendments are made in relation to legal aid provision. These amendments are to the Access to Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2003 and relate to legal aid for proceedings relating to anti-social behaviour orders and to proceedings under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

Police and Criminal Evidence

42. Amendments being made to the Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989 alter the police authorisation level required for certain procedures; introduce trigger powers for entry into premises in particular circumstances; and create new powers to allow police to attach conditions to bail before charge.

Penalties

43. New sentencing powers extend the maximum penalties available to the courts for certain offences relating to knives, though they also include crossbows and other offensive weapons. Broadly the new penalties will relate to offences of possession, manufacture and sale. The provisions introduce a standard set of maxima – 12 months’ imprisonment and/or a £5000 fine where a person is convicted in a magistrates’ court; 4 years and/or an unlimited fine for convictions in the Crown Court.

44. New powers are also created for courts to impose a driving disqualification for any offence. This is designed to allow courts to disqualify from driving individuals convicted of offences which might involve vehicles but are not ‘motoring’ offences per se.

Proving Execution of Arrest Warrants

45. New provisions are proposed to enable a wider range of magistrates’ courts to hear the proving of the execution of arrest warrants.

46. In appropriate circumstances an arrest warrant issued in one County Court Division could be proven in the Division of arrest or in a County Court Division which adjoins the Division of arrest. The transport of defendants across court divisions would be reduced providing a more effective and efficient procedure.

Anti-Social Behaviour Orders

47. Two adjustments are made in relation to legislation relating to anti-social behaviour orders. To allow existing interim order powers to operate more effectively, applications will be possible without notice, and a technical amendment is also included to enable rules of court to be made for special measures for witnesses.

Youth Justice

48. A number of adjustments are made to youth justice legislation. Rehabilitation periods for youth conference orders, reparation orders and community responsibility orders are clarified. Powers are also created to allow children aged 17 who require custody to be accommodated in a juvenile justice centre if no suitable accommodation is available in a young offenders centre; clarifying the period a youth conference order remains in force; removing the requirement for a care order to be suspended whilst a child is serving a juvenile justice centre order; and the powers of the youth court to notify the appropriate authority where it has concerns regarding the welfare of a child are extended.

Part 6 -Supplementary

49. Part 6 provides for the statutory procedures for regulation, order or rule making powers by the Secretary of State; the making of incidental or consequential provisions and any transitory transitional or savings provisions; amendments and repeals.

Committee’s Consideration of the Proposed Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007

General Comments

50. The Draft Criminal Justice (Northern Ireland) Order 2007, which the Committee was told will be the largest Criminal Justice Order that has ever been introduced here, covers a wide range of justice, policing and community safety issues. These are matters that affect the whole of society and many are frequently in the public eye, from the sentencing, release and management of dangerous offenders, through to the disorder caused by drinking in public places and the nuisance caused by quad bikes and mini-scooters.

51. The Committee supported the four key purposes behind the Draft Order as explained by NIO officials:

- enhancing public protection

- improving provision for the management of dangerous offenders

- improving the supervision and rehabilitation of offenders in the community

- enhancing public confidence in the criminal justice system.

52. The Committee saw the proposals as timely and Members welcomed the opportunity to engage directly on these very important issues with representatives of the NIO, DoE, DSD and a number of key agencies at a time when the future devolution of justice and policing is under consideration. Representatives from the departments and agencies also expressed their welcome for the opportunity to discuss the implications of the draft legislation with local political representatives.

53. This section of the Report sets out the Committee’s conclusions and recommendations on the various issues covered within the Draft Order taking account of the written and oral comments provided by the organisations who gave evidence.

Recommendation

54. The Committee expects the Secretary of State, the NIO and, where appropriate, other departments to consider seriously the conclusions and recommendations made in this report and to accept them.

Sentencing and Licence Arrangements (Articles 3 to 34)

55. The Committee heard evidence from a range of organisations in relation to the new sentencing and release on licence proposals and in particular the provisions relating to the new public-protection sentences. Members were pleased to hear that the Northern Ireland Office had fully engaged with organisations such as the Probation Board before drafting the legislation.

56. The Probation Board, the Prison Service and Criminal Justice Inspection were generally supportive of the proposals and the Committee welcomed the fact that the senior management within the probation and prison services had already been working together and with the NIO to plan implementation of these significant new arrangements. Representatives of these two key agencies also assured the Committee that they had been involved in discussions with the NIO to ensure they would have the resources necessary to implement the revised systems flowing from the Draft Order. Both organisations were already planning implementation and, while they acknowledged the challenges ahead for their organisations, both were able to assure the Committee that they would be able to cope with the increasing workload and demands of the new arrangements.

57. Some concerns were expressed by the NI Human Rights Commission (NIHRC), the Chairperson of the Life Sentence Review Commissioners and the Northern Ireland Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (NIACRO) about the proposed new indeterminate custodial sentence (ICS) and extended custodial sentence (ECS) arrangements, which are already in operation in Great Britain. There was some disquiet that these had not been based on research or evidence by penologists, but rather had been a political reaction to public concern about dangerous crime and the risk of serious harm to the public.

58. The concept of indeterminate sentences caused particular concerns for NIHRC and NIACRO. They suggested that an ICS would appear to be punishing people for what they might do as well as what they had done. The NIHRC expressed serious concern with the possible psychological impact on prisoners given such a sentence and with the breadth of the list of specified serious offences for which an ICS could be given. NIHRC asked that courts should be provided with a consistent assessment process for all cases where an indeterminate sentence is considered.

59. The Committee was given evidence given by Criminal Justice Inspection and others that lessons had been learnt from experience in England and Wales where the Prison and Probation Services had been initially overwhelmed by the imposition of short-tariff indeterminate sentences.

60. The Committee also received evidence that the proposed legislation had been drafted to take account of the problems encountered and experiences of the public-protection sentences in England: by removing the presumption of dangerousness; by giving more discretion to courts in choosing between ECS and ICS; by providing for a minimum 1-year tariff for ECS and a 2-year minimum for ICS; and by providing that these sentences would be able to be imposed only on indictment.

61. Members therefore gave a general broad welcome to the proposals including: indeterminate and extended custodial sentences; the ending of automatic 50% remission; the proposed new parole and licence arrangements; and the compulsory supervision of all offenders on licence after release to address offending behaviour and reduce the likelihood of reconviction.

62. The Committee also welcomed the expressed intention of the NIO to work with the Lord Chief Justice’s Office and the Judicial Studies Board to provide whatever assistance is needed to prepare the judiciary for the implementation of these new sentencing arrangements. The Committee suggested that the development of guidelines and courses by the Judicial Studies Board for the judiciary would be crucial to ensure that the new public-protection sentencing arrangements are implemented strictly in accordance with the legislation and that the judiciary are fully aware of the problems and experiences of inappropriate indeterminate sentences in England and Wales.

Recommendation

63. The Committee recommends that guidelines and courses should be developed to assist the judiciary in the introduction of these new measures.

Recommendation

64. The Committee recommends that consideration should be given by the NIO to the most appropriate mechanisms to inform sentencing policy.

Recommendation

65. The Committee recommends that, as a matter of good practice, the new sentencing and licence arrangements should be subject to ongoing review by Government in consultation with other key agencies so that any implementation problems can be rectified quickly in conjunction with those agencies and if necessary the policy and legislation amended.

66. The Committee was very conscious of the need for Government to properly resource the implementation of these significant new arrangements. Furthermore the Committee agreed that it was vitally important to explain all the main changes in the law to the general public so that there should be no misunderstanding about the new law and arrangements including, for example, the rules relating to dangerous offenders and the fact that there would be no retrospection, or the ending of automatic 50% remission. The Committee’s conclusions and specific recommendations on the issues of resources and publicity are covered in greater detail later in this report.

Recommendation

67. The Committee recommends that the main changes being introduced by the Draft Order, particularly those around the public protection sentences, ending of automatic 50% remission, and the fact that the changes cannot be applied retrospectively, must be publicised and explained to the general public.

Curfews and Electronic Monitoring (Articles 35 to 44)

68. The proposals to give courts additional powers to impose curfew and electronic monitoring of offenders, as a condition of bail, as part of a licence condition, as part of a community disposal, or as part of a juvenile justice order, were broadly welcomed by PBNI, the Prison Service and CJI as a means of strengthening the management of offenders in the community. No concerns were raised during evidence and the Committee supported the proposals.

Supervised Activity Orders (Articles 45 to 47)

69. The Committee and organisations who gave evidence welcomed the proposal to use supervised activity orders in the community as an alternative to imprisonment for offenders who default on fines. The Committee noted that the court would still have the option of a custodial sentence and that if a person breached a supervised activity order, the penalty would be a heavier custodial period than in the first instance.

70. Members were pleased to hear the Probation Board’s evidence that the supervised activities, for which PBNI would be responsible, would be geared wherever possible towards retribution for the original offence (e.g. where a fine had been imposed for a graffiti offence, a supervised activity might involve removal of graffiti). PBNI indicated that offenders would undertake purposeful, unpaid work for the benefit of the community, and related to the offence committed. The NIHRC stressed the importance of resources to ensure that appropriate activities with a restorative element are made available.

71. The Probation Board indicated that it would identify areas of need with community and voluntary groups and ask these groups how it can work with them to allow offenders to show that they really are sorry for their offences.

Recommendation

72. The Committee commends the stated intention of PBNI to ensure that as far as possible supervised activities would be directly related to some sort of reparation for the initial offence; and recommends that PBNI should work closely with the relevant community and voluntary groups to achieve this objective.

Parole Commissioners (Articles 48 and 49)

73. The role given to the Parole Commissioners under the Draft Order was welcomed by organisations giving evidence and supported by the Committee. The proposals will see them take on additional duties to those of their predecessors, the Life Sentence Review Commissioners. Parole Commissioners will be responsible for three categories: prisoners given mandatory or discretionary life sentences; prisoners given indeterminate custodial sentences; and prisoners given extended custodial sentences. That will entail a greater volume of work for commissioners, and the sentences are likely to be subject to more public scrutiny. Therefore commissioners will have to demonstrate that decisions have been taken properly and consistently and can be defended in public.

74. The Committee heard evidence from Mr Peter Smith QC, chair of the current panel of Life Sentence Review Commissioners, who indicated that the NIO had engaged already with the Life Sentence Review Commissioners in relation to resources needed by the Parole Commissioners to exercise their extended functions. Mr Smith indicated that the Life Sentence Review Commissioners had no corporate view on the proposals and that he was offering his personal opinions on the provisions. He subsequently highlighted the likely increase in prison numbers flowing from the new sentencing arrangements and the greater pressure on the facilities for prisoner rehabilitation and post-release supervision. In his annual report 2007 to the Secretary of State, the Chair of the Commissioners had also pointed out that failure to make sufficient resources available would result in the development of a vicious circle of:

- prisoners being inadequately prepared for release;

- panels not giving release directions because prisoners have been inadequately prepared or because of concern as to the effectiveness of poorly resourced post-release supervision arrangements; and

- further reduction in preparation and post-release supervision capacity because resources have been dissipated in keeping prisoners in prison.

75. The Committee supported these sentiments and welcomed the NIO’s stated intention to increase the resources and, if necessary, to recruit more parole commissioners. The NIO had also indicated that it would be a step-wise enhancement because, initially, it was estimated that there would be only a marginal increase in cases for consideration by the parole commissioners. Representatives of Criminal Justice Inspection had suggested to the Committee that because decisions on parole are likely to be subject to more public scrutiny under the new arrangements, one option might be to use fewer parole commissioners but on a more regular and intensive basis than at present to ensure consistency of approach. The Chair of the Commissioners however indicated that there had been no problems with consistency during the 5 years of their tenure to date.

76. The Committee acknowledged that there would be a staged increased workload for the Parole Commissioners including the new categories of ICS and ECS prisoners and the likelihood of seeing some prisoners on numerous occasions. While recognising the suggested option of using fewer commissioners on a more regular basis as worthy of consideration, the Committee felt that the NIO and the Parole Commissioners were best placed to make these decisions based on their knowledge and experience.

Recommendation

77. The Committee recommends that the NIO should work closely with the Parole Commissioners on an ongoing basis to achieve a proper balance between the number of commissioners (and administrative support staff) and the workload of individual commissioners in order to ensure that there will continue to be a consistency of approach in decision-making under the proposed new release on licence provisions.

Risk Assessment and Management (Articles 50 to 52)

78. The Draft Order includes proposals to put on a statutory footing the Multi-Agency Sex Offender Risk Assessment and Management (MASRAM) arrangements and to extend the procedures to violent offenders. These proposals were welcomed and strongly supported by the Committee.

79. Members were assured that all the relevant agencies will be required under the new legislation to work together and share information to manage effectively the risk that serious sexual and violent offenders in the community present, thus enhancing the protection of children and adults, particularly those who are vulnerable.

80. The Committee was impressed by the evidence received from Criminal Justice Inspection and the NIO indicating that, in their view, we already have some of the best multi-agency risk-assessment and risk-management arrangements in place. The Committee commended the various agencies for the work they have done to date in cooperating to protect the public but acknowledged that there can be no room for complacency when dealing with dangerous offenders. Members were reassured in this respect by the evidence from PBNI that they were already working closely with PSNI and others to implement a recommendation from CJI for the development of a co-located public-protection team. This would involve the relevant agencies coming together physically to further enhance the oversight and management of those offenders who present the greatest risk in the community. While the Committee acknowledged that risk could never be completely eliminated it urged the relevant agencies to do all in their power to minimise risk and considered that the proposal for a co-located public-protection team would certainly help to achieve this objective.

81. As part of their evidence NIO officials indicated that they were considering highlighting the MASRAM arrangements in the media in Spring 2008 so that the public would be better informed on the procedures in place to protect them. The Committee supported this proposal.

Recommendation

82. The Committee recommends that the proposal for a co-located public-protection team should be developed further as a matter of urgency so that this becomes a reality as soon as possible. The Committee further calls on the NIO and the various agencies involved to ensure that this team is properly resourced and kept under review, and that the highest priority is given by all the agencies involved to the important work done under the MASRAM arrangements.

Probation Service

83. During evidence taken from the Probation Board the Committee was given details about the current probation workload and the anticipated increase in cases flowing from the proposed new sentencing, licence and supervision arrangements. At present PBNI produces around 6,000 reports a year to the courts to assist judges and magistrates in setting appropriate sentences. It manages nearly 4,000 people in the community. The proposed legislation will increase the number of people under their supervision by around 50%. PBNI will have statutory responsibility for offenders when they leave prison as opposed to the current voluntary engagement. NIACRO in its evidence emphasised the importance of agencies cooperating in support of individuals on release as crucial to support resettlement and to reduce re-offending rates.

84. The Committee was encouraged to hear from PBNI that reconviction rates in Northern Ireland are lower than elsewhere throughout these islands, although this fact has not been well publicised. PBNI confirmed that it and other criminal justice organisations had worked closely with the NIO on the development of the policies behind the draft legislation and that PBNI was supportive of the proposals and welcomed the central role given to it in the future management of offenders.

85. PBNI reported that it allocated some £1.2 million a year to the voluntary and community sector to help the probation service manage offenders in the community. The Committee welcomed the undertaking by PBNI to continue to work and develop their links with community and voluntary organisations to complement their work.

86. PBNI is currently consulting on its draft corporate plan for 2008-2011 and the Committee commended its broad central themes of:

- more joined-up thinking and action across Government in dealing with offenders

- end-to-end offender management (the same probation officer would take care of the initial pre-sentence report, ensure the offender signs up to appropriate offender-behaviour courses while in prison, and manage the offender during the probation period and after release from prison).

87. The Committee further welcomed the evidence given by PBNI that responses to its recent recruitment exercises had been very positive, that the organisation has a good professional reputation and that the Board intends to phase its recruitment to cope with the expected increase in workload over the coming years. The Committee also welcomed the establishment of a strategic joint steering group involving the Prison Service, PBNI and other partners to focus on offender behavioural programmes.

Note: The Committee’s recommendations relating to the probation and prison services appear at the end of the following section on prisons.

Prison Service

88. Representatives of the Northern Ireland Prison Service in their evidence indicated that the Service was in a transitional phase. Whereas in the past it had been focused largely on security and the management of paramilitary prisoners, its statement of purpose now referred explicitly to public protection and its focus is moving to resettlement and offender management. The proposed Order would add momentum to this transition as its objective is to focus prison on those who need it most, with longer sentences for the most serious offenders and alternatives to custody for persons who are not a risk to others.

89. The Committee heard that some of the more dangerous offenders could not at present be compelled to address their offending behaviour but the proposed new public protection sentences, licence and parole arrangements should encourage offenders to engage with the prison and probation services to reduce the risk they pose. The Prison Service indicated that there is agreement between prison service management and the prison officers’ association on the need to develop staff for active engagement with prisoners including programme facilitation. A mandatory 2-day development course is being delivered to all main grade officers and a 5-day course had already been delivered to all middle managers.

90. Statistics provided to the Committee indicated that since 2001 there had been a 62% increase in the prison population. On average over the last six years the prison population had increased over 10% per annum. Remand prisoners now constitute 35% of prison population while the life-sentenced population had doubled from 88 prisoners in 2001 to 173 now. The current overall prison population was currently 1,432 and it was estimated, that this could increase to 2,700 by 2022 (including ICS and ECS prisoners).

91. Under the proposed new arrangements the Prison Service will provide additional suitable offending behaviour programmes, education and training for prisoners with a public protection sentence. In addition to existing expenditure (the total prison service budget for 2007/08 is £132 million) the prison service plans to invest a further £4.7 million over the next three financial years to implement the changes. This will include investment in education and psychology services to recruit and train new staff to undertake risk assessments, provide programmes and work directly with dangerous offenders to reduce their risk, and to put the necessary structures in place to manage the process. Representatives stressed the importance of working closely with NI Departments and agencies, especially DHSSPS, DEL and DE and the transfer of funding (some £6 million to the Health Service for the healthcare of prisoners) will assist in this respect.

92. The Committee was provided with an estimate from the prison service that up to 65% of prisoners may have some form of mental health problem or personality disorder. This presents a challenge for the system in terms of the regime to manage their behaviour, provide appropriate care and reduce the risks they pose before and after release. The Committee was informed that the Bamford Committee had recommended a new fully secure mental health facility, as had the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee.

93. The Committee welcomed confirmation from the Director of the Prison Service that while the Probation Board would have a greater role in working with offenders in prison, there was no blurring or conflict of roles and the two agencies were continuing to work closely together to deliver on the proposals. The Director also agreed with the sentiment expressed by CJI in its evidence that implementation of the Draft Order would require the prison service to step up its game significantly. He was confident however that the necessary resources would be available to implement the changes and that the Prison Service could deliver those changes. They had recently held a meeting with their counterparts in England and Wales to discuss their implementation of the Criminal Justice Act 2005 and to learn from their experiences, problems and challenges.

94. The Chair of the Life Sentence Review Commissioners, CJI, the NIHRC and NIACRO all raised with the Committee the potential for legal challenges if prisoners could not avail of behaviour-change programmes due to lack of resources. A court case in England (Wells v the Parole Board 2007) had highlighted the problem of the non-delivery of programmes for prisoners serving public-protection sentences and the Committee heard that similar problems here could result in prisoners not being released early by the parole commissioners because there would not be evidence of a reduction in risk. The effect would be that prisoners could be punished beyond the period of the actual punishment element of their sentences.

95. The Committee was assured however that PBNI is having full discussions with the Prison Service about the regimes that will be required to deliver behaviour-change programmes and that these would be central to the operation of the new arrangements within prisons. The evidence presented to the Committee of an ongoing high level of cooperation between the Probation and Prison Services and the fact they have agreed a resettlement strategy and a resettlement implementation plan was also welcomed. Criminal Justice Inspection in its evidence had indicated that it was committed to probing the delivery of programmes for prisoners serving ICS, ECS and life sentences and this too was welcomed.

Lack of an Open Prison Facility

96. Mr Smith QC, Chair of the Life Sentence Review Commissioners, in his evidence had cited the lack of an open prison in Northern Ireland as a major disadvantage. For prisoners who may receive indeterminate custodial sentences, he suggested that the facility of an open prison would be an important asset in testing and preparing them for eventual release. He stressed that the lack of such a facility created immense complications in the assessment of risk posed by prisoners whom commissioners are considering releasing into the community and that the issue also affects the preparation of those prisoners for leading constructive lives on leaving prison. He made the comparison with England and Wales where life-sentence prisoners are not released unless they have spent three years in an open prison. He acknowledged that we do have a well-organised and well-run prisoner-assessment unit, but said that this was a very different facility to an open prison and that the duration of a standard course in the prisoner-assessment unit here is only nine months.

97. The Director of the Prison Service told the Committee that the service was doing what it could within the existing facilities at different locations to remedy the open-prison gap. He agreed that the prisoner assessment unit in Crumlin Road Prison was not a wholly satisfactory facility and could house at most 20 prisoners. It is not a fully open prison of the type used elsewhere. There were also facilities in Magilligan which has 82 places for prisoners who are approaching the end of their sentences. Although they had not chosen to send life-sentence prisoners to Magilligan that decision would be kept under review as they considered the nature of the population to be housed in the proposed new prison at Magilligan. It would be important to identify accommodation that would give appropriate prisoners more responsibility for their own arrangements, catering etc. The Committee heard that the new landing created for women in Ash House allowed them to have their own keys and make decisions about their lock-up times and catering arrangements.

98. In addition the Prison Service has two facilities in Mourne House, Maghaberry where women prisoners were previously held. These currently contain about 25 life-sentence prisoners, who are potentially the individuals within the last three years of their sentence. These prisoners must meet certain criteria in order to demonstrate that they are ready for release. They have greater independence and responsibility for their living arrangements, and that is as close as they can get at present to an open prison in the Maghaberry complex, although it was acknowledged that prisoners there are still behind a high wall.

Other Prison Issues

99. The Committee welcomed the statement that an interim report on proposals for women in custody (and the community) is due to be put to Ministers by end February 2008. CJI had also highlighted as a priority the provision of a dedicated female prison facility and this was supported by the Committee. The Committee also welcomed the indication from Criminal Justice Inspection that it would be reporting on Offender Hostels early in 2008.

Recommendation

100. The Committee recommends that the Probation and Prison Services continue to work closely in partnership to ensure that all relevant aspects within the proposed legislation can be delivered effectively and efficiently.

Recommendation

101. The Committee recommends that the Prison and Probation Services ensure that all relevant prisoners have access to appropriate basic skills training and behaviour-change programmes; and that the necessary resources should be deployed to facilitate such programmes so that prisoners may prepare themselves to be acceptable for release.

Recommendation

102. The Committee, while acknowledging the competing priorities within the prison service estate, recommends that the Government should re-examine the proposal for an open prison in the light of evidence provided to the Committee.

Road Traffic Offences (Articles 53 to 65)

103. The Department of the Environment provided evidence to the Committee on the Road Traffic Offences within Part 4 of the Draft Order. Officials confirmed that the proposed new road traffic offences reflect those which already exist in England and Wales (under the Road Safety Act 2006 and the Police Reform Act) and that the measures are deemed to be good road safety measures for Northern Ireland.

104. The Committee supported the proposed new offences for: causing death or grievous bodily injury by careless or inconsiderate driving, or by driving while unlicensed, disqualified or uninsured; and for the use of speed assessment equipment detection devices which can detect or interfere with police speed detection facilities. There was also support from the Committee for the increased penalties for failure to stop and furious driving; and for the power to require specimens of breath at roadside or at hospital.

Alcohol Interlock Ignition Schemes (Articles 59 and 60)

105. Officials from the Department of the Environment confirmed that the Department for Transport in England had been running a pilot alcohol interlock ignition scheme over a two-year period, primarily in Birmingham and Manchester. The pilot programme had now concluded but the report on it had not yet been published. Findings from the pilot will form the basis of decisions on whether such a scheme will be made available throughout England and Wales. The Draft Order provides the power to introduce a similar scheme in Northern Ireland.

106. The DoE officials explained that the scheme is aimed at problem drinkers who have difficulty in kicking the habit and trying to encourage them to be able to drive without taking any alcohol. There were mixed reports from around the world about the use of these schemes. Several countries introduced the scheme in pilot form some time ago and have since made it permanent. Other countries have experimented with the programme but have decided that it had not been such a success. However it was DoE’s view that there should at least be an experimental period and examination of the results before deciding whether the programme is appropriate for Northern Ireland. Members were informed that the device has the capability to recognise the driver’s breath, similar to a fingerprint, and will recognise whether each breath sample is the same as the initial sample.

107. The Committee supported the proposal to test the scheme over an experimental period in Northern Ireland as another part of the Government’s campaign against drink-driving. The other driving offence provisions (in Articles 61 to 63) were also supported by the Committee.

Seizure of Vehicles Causing Alarm, Distress or Annoyance (Articles 64 and 65)

108. The Committee heard evidence from the DoE and the PSNI regarding the new powers to be given to the police to deal with the anti-social use of motor vehicles on or off public roads. The problem is generally regarded as a public nuisance issue but there have been cases where people have been tragically killed or maimed as a result of the use of vehicles such as quads or mini-scooters. Similar provisions are already in force in England and Wales and have proved to be very effective in dealing with the problem.

109. DoE officials explained that vehicles, whether lawfully or unlawfully held, that are causing alarm, distress or annoyance can be seized and disposed of by the police. The police also have the right to go onto premises, other than private dwellings, in pursuit of offenders who may have headed down alleyways or into public parks. Police cannot go into a private dwelling to seize them. The PSNI explained that in practice the police will not be seizing vehicles unless and until the rider has been previously issued with a warning for riding the vehicle in a manner causing alarm, distress or annoyance. The Committee strongly supported these provisions.

Test Purchases of Alcohol (Article 66)

110. This provision would allow a person under 18 years of age, under the direction of a police constable, to enter licensed premises to seek to purchase alcohol. The Committee heard evidence from representatives of the NIO and the Department for Social Development who indicated that, since similar provisions had been introduced in England and Wales, there had been a dramatic fall in sales of alcohol to under-age people (from 50% of outlets tested in 2004 down to 15% in 2007). It was confirmed that the police must obtain parental consent in writing for the young person to be involved and must take all reasonable steps to avoid any risk to the young person.

111. In their evidence to the Committee, representatives of NIACRO and the NIHRC expressed strong concerns about the proposal to use children to entrap retailers. Although NIACRO supported measures to cut the supply of alcohol to under-age people it suggested that better education and community supports offered a more positive way to address the issue in the longer term.

112. The NIHRC in its evidence and opposition to the proposal cited the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention states that:

- in all actions concerning children the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration (Article 3);

- no child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his or her honour and reputation (Article 16);

- States Parties shall protect the child against all other forms of exploitation prejudicial to any aspects of the child’s welfare (Article 36).

113. NIHRC did not consider it to be in the best interests of any child to be used to promote the commission of a criminal offence in an entrapment situation and asked what possible benefit there could be to the child to be involved in such a scheme. Representatives suggested that the police could mount their own undercover operations rather than use this power. They were also concerned that it would be the vulnerable child who is known to the police who might be asked to participate, maybe to avoid a caution or an ASBO. The Commission was further concerned about the risks to the safety of a young person who assisted the police in the entrapment of a licensee, suggesting that it might lead to threats or risk of physical violence from persons subsequently charged or others.

114. The NIHRC also challenged the NIO’s conclusion that this power would have no adverse impact between the various section 75 groups. Given the possible risks to the child and the potential for breach of the UK’s commitments under international human rights law, the Commission said it could not endorse the NIO’s conclusion that this power ought not to be submitted to a full Equality Impact Assessment under Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

115. The Committee acknowledged and appreciated the very strong concerns expressed about the possible risks to young persons used by the police under the proposed scheme. However it was the Committee’s view that we have a drink culture and a problem with alcohol dependency and that these issues need to be tackled on many different fronts. It acknowledged that the licensed trade and councils are already doing some good work through for example the Challenge 21 campaign, which encourages off-licences etc to challenge people who look like they are under 21 years of age. Members considered, however, that such schemes rely on the goodwill of the retailers and that these types of campaigns and general education about alcohol alone are unlikely, because of their voluntary nature, to be effective in reducing significantly the sale of alcohol to young people.

116. Against the concerns expressed the Committee weighed the evidence that the test purchase scheme had already been in operation for a number of years and had proved to be an effective deterrent in England and Wales. Indeed the Committee heard that some outlets there had lost or had their licences reviewed due to persistent sales to minors as revealed by test purchase schemes. Members also considered that there would be wider benefit to children generally and to society if the sale of alcohol to minors could be effectively reduced. The Committee was further reassured by the wording of the Draft Order which provided that a parent of the child would have to give written consent, and that the police must be satisfied that all reasonable steps have been taken (or will be taken) to avoid any risk to the welfare of the young person.

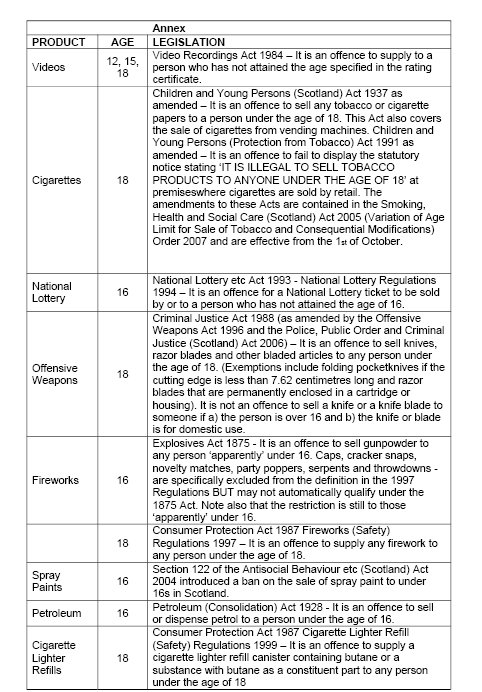

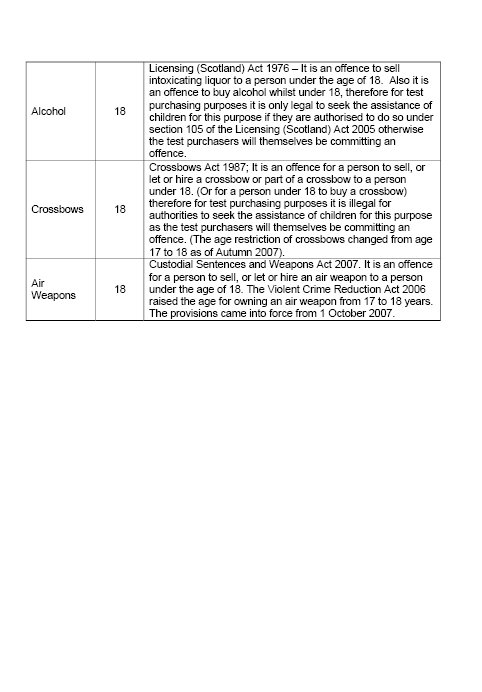

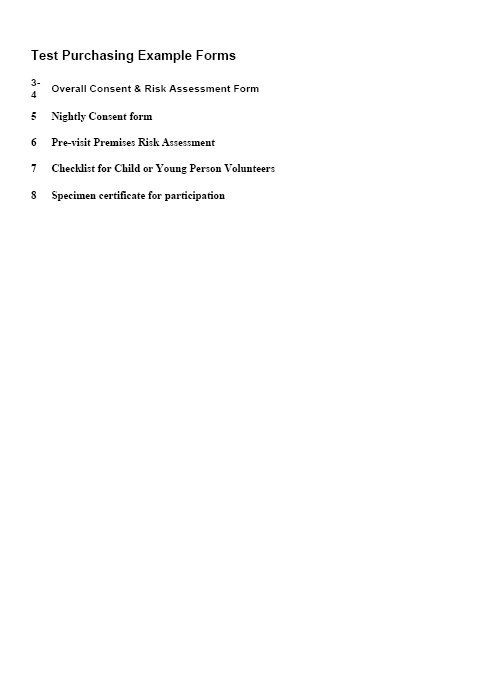

117. On balance therefore the Committee supported the proposal, subject to an Equality Impact Assessment being undertaken. The Committee recommended that in implementing the scheme the police should take account of experiences of other police forces in England, Wales and Scotland. The Committee was informed that a pilot scheme had recently been successfully completed in Fife, Scotland and that Good Practice Guidelines on the operation of test purchase schemes had been produced for local authorities and police forces in Scotland. A copy of the Scottish Guidelines is included as an Annex to the Committee Minutes of the meeting on 21 January 2008 (see Appendix 1).

118. The Committee recommended that the PSNI should publicise its intentions in advance so that retailers would be fully aware of the scheme and the consequences of selling to minors. Furthermore the Committee proposed that the scheme should only be operated under strict controls, including lower and upper age restrictions and supervision of young persons involved, and these issues should be covered in guidelines for relevant trained police personnel. The Committee would expect that similar success to that achieved in England, Wales and Scotland could be achieved here over the next few years once the scheme is operational.

119. The Committee also discussed other possible means of tracking retailers who sold alcohol to minors. These included exploring the possibility of forcing off-licences etc to use carrier bags that clearly identify the retailer rather than plain blue plastic bags; and the practice used in the USA where items of alcohol are bar-coded enabling them to be tracked to point of purchase.

Recommendation

120. The Committee recommends that the NIO should undertake an Equality Impact Assessment on the test purchase scheme taking account of the views and concerns raised by the NIHRC.

Recommendation

121. The Committee recommends that the PSNI should publicise widely in advance that they will be using this test purchase power to detect retailers who sell alcohol to persons under 18.

Recommendation

122. The Committee recommends that the PSNI should develop operational guidelines for personnel involved in the test purchase scheme. These should address specifically issues such as the ages of young persons to be used and the need to ensure their welfare is protected. The guidelines should also make it clear that in no circumstances should a vulnerable young person be considered for use in the scheme.

Recommendation

123. The Committee recommends that DSD and PSNI should also consider the feasibility of schemes used elsewhere for tracking sales of alcohol to minors.

Alcohol Consumption in Designated Public Places (Articles 67 to 71)

124. Under these proposals, as explained initially to the Committee by NIO officials, councils would continue to have the power to designate areas where public drinking may not take place. However, they must do so in consultation with the police and the areas would have to be places associated with disorder and alcohol-related nuisance. It would not necessarily be an offence to consume alcohol in a designated area (this is currently an offence). It was explained that drinking alcohol is not the issue but rather the anti-social aspect of it, including failure to stop drinking when requested. Under the proposals the police would have discretion to allow drinking that does not cause nuisance.

125. Further evidence on these proposals was provided by officials from the Department for Social Development and the PSNI. As currently drafted the Order would give the police a power to require a person in a designated public place (a) not to consume intoxicating liquor or (b) to surrender any such liquor in his possession. The new provisions would allow the police to issue a fixed penalty notice, to be set initially at £50, as an alternative to prosecution. The Draft Order provides for district councils to designate the public places where drinking would not be permitted (as they do at present under their bye-laws) and for the police to enforce the provisions.

126. The Committee heard evidence, and Members were already aware from their involvement in councils, that the current drinking-in-public bye-laws are widely regarded as inadequate. There is no power at present to remove alcohol from persons in designated places, resulting in offenders simply moving to nearby undesignated locations and continuing to drink. The Committee was informed that during consultation by DSD in 2003/04 there had been substantial support for the introduction of provisions to allow for confiscation of alcohol and for fixed penalty notices.

127. The Committee was told that following discussions between DSD and NIO the respective Ministers had agreed that a balance should be struck so that problematic public drinking could be tackled on the spot through providing the police with appropriate powers, whilst also encouraging people to enjoy public places more fully. The Committee was also told that during the 2003 consultation councils were not asked directly about a blanket ban, but that 4 of the 16 councils that responded had suggested that a blanket ban be considered.

128. On the question of enforcing the proposed powers, the Committee was informed by DSD that the Minister for Social Development believed that district councils’ involvement in on-the-ground enforcement was a matter that would be best considered in more detail after decisions on local government structures have been taken, and in the context of the review of public administration’s consideration of their involvement in wider licensing functions. In the meantime, councils would continue to designate the areas in which the new provisions would apply and take forward any prosecutions.

129. In its evidence the PSNI indicated that it saw the enforcement of the new provisions as one primarily for councils but with support provided by the police where council officials got into difficulty, for example, if there was a breach of the peace/assault etc. PSNI representatives referred to the discussions between the police and DSD for a strengthening of the law which had been ongoing since 2002. The initial proposals had envisaged joint police and council enforcement powers. The PSNI view was that the enforcement of the drinking in public places provisions is not a core policing issue nor a policing priority and that it would be more appropriate for councils to take the lead on enforcement as they do in other areas such as street trading, dog fouling, noise, litter and the smoking in workplaces ban.

130. The PSNI would therefore welcome joint powers of enforcement, with district councils taking the lead and police being involved in joint pro-active operations, where necessary, with council enforcement teams. The PSNI suggested that council officers in the course of their other duties may come across breaches of the drinking law and could then take the appropriate enforcement action.

131. During its discussions the Committee discussed the various disorder and nuisance problems caused by drinking in public places including the intimidation of the general public. While the new provisions allowing confiscation of alcohol and fixed penalty notices were welcomed by the Committee, Members thought that the ongoing problem of designating and further designation of areas by councils would remain a challenging issue, including the erection of appropriate signs and the tendency for offenders to find a way round the designated areas by simply moving to other locations.

132. Furthermore the Committee was concerned about the additional burden being placed on councils by the new designation provisions which would allow them only to designate areas that have been associated with disorder and alcohol-related nuisance. Members were very concerned about this fundamental change in policy which would permit persons to drink in designated public places unless asked to stop by a police officer.

133. The Committee examined a proposal to reverse the underlying policy to one whereby councils should designate the places and times where and when drinking should be permitted in public. In these circumstances the policy would be much easier explained and understood by the general public and the consumption of alcohol in certain places (e.g. parks for picnics) or at authorised public events would be permissible.

134. On the question of enforcement, the Committee considered the evidence provided to it and concluded that there should be no change in the Order as drafted. Members felt strongly that tackling the inappropriate use of alcohol in public places should be a policing priority given the threat to community safety and the potential for crime and public disorder arising from this widespread problem. The Committee recommended that responsibility for confiscation of alcohol and fixed penalties should be solely for the police to enforce at this stage. In the Committee’s view given the scale of the problem involving groups of young people it would be unrealistic to expect that a council official could command the same respect as a police officer in approaching such persons.

135. Furthermore the Committee could not agree with the PSNI view that this issue was comparable to the enforcement of smoking, litter, street-trading or dog-fouling provisions. The presence of groups of persons under the influence of alcohol made this a much more serious public-order issue and one that the police need to view as a front-line policing priority. The Committee suggested that the issue should however remain under review and that it might be possible in the future as the stricter laws are enforced and the general public are better educated about the law, for council officials to be more involved in enforcement.

Recommendation

136. The Committee recommends that the Draft Order should be amended to retain the prohibition on drinking in designated public places (as is the case with current bye-laws) but also retaining the proposed new provisions regarding confiscation and fixed penalties; and further recommends that the DSD should examine the operation and effectiveness of the new law, after it has been in operation for one year, and undertake further consultation on whether there should be a wider ban.

Recommendation

137. The Committee recommends that the police should remain primarily responsible for enforcement of the provisions and that the PSNI and the Policing Board should consider making it a policing priority to address the potential for disorder arising from inappropriate drinking in public places.

Prison Security and Offences (Articles 72 to 77)

138. These proposals make a number of changes in relation to prisons, including longer sentences for helping a prisoner escape and for bringing banned items such as alcohol, drugs and mobile phones into a prison. There were no specific concerns raised during evidence to the Committee and the Committee supported these proposals.

Live Links (Articles 78 to 82)

139. The Draft Order gives a court power to give a live link direction (allowing the accused to be treated as present in court when attending via a live link) to certain categories of proceedings: preliminary hearings, sentencing hearings (only where the offender has given his consent) and to appeals under the Criminal Appeal Act.

140. Concerns about these proposals were expressed by NIACRO and NIHRC. NIACRO said that delays in the system that provide for constant remanding and the extended use of live links needed to be addressed. They saw this as an ongoing scandal of the system that affected both victims and offenders. NIACRO objected to the use of live links for sentencing believing that in a small jurisdiction the system should be able to ensure that offenders receive their sentences in person

141. The NIHRC was content with the Draft Order’s provisions in respect of sentencing hearings because in these circumstances the direction of appearance by live link could only be made by the court with the consent of the offender. The Commission’s concern was that this would not be the case in respect of a direction relating to a criminal appeal in the Court of Appeal. While the live link direction could not be made without the parties having an opportunity to make representations, the consent of the offender would not be required. The concern was that a defendant could consequently be denied the opportunity to be present in court in person. NIHRC complained that little evidence was provided by way of rationale for this interference with the long-standing safeguards surrounding the right to a fair trial. The NIO, it said, had cited two reasons: improved security of prisoners and reduction of delays in court hearings relating to transportation of prisoners to the Court of Appeal, but NIHRC said that no statistics had been provided regarding either breaches of prisoner security or court delays.

142. Further concerns were raised by NIHRC in relation to Article 81, which deals with conditions to be met for the giving of evidence by live link by the vulnerable accused. While the Commission considered that attendance by a live link may be in the interests of the vulnerable accused in certain instances (e.g. in a domestic violence case) it contended that in other circumstances, particularly for vulnerable young persons, being alone in a room with a live link might only serve to exacerbate the inability of the accused to fully appreciate the nature of the proceedings. NIHRC urged that more thought should be given to a range of measures to support the vulnerable accused. The Commission’s conclusion was that the proposal to extend the use of live links was mainly a cost-saving exercise that might not serve the interests of justice nor foster respect for the criminal justice system.

143. The NIO provided further information to the Committee about the proposals after hearing the concerns raised. On the question of no right of appearance at an appeal hearing, the NIO confirmed that there is no absolute right to a person being present at an appeal hearing anyway. For example, under the Criminal Appeal (NI) Act 1980, Section 24, a defendant has no right in law to be present if it is on a point of law. He can attend with the Court of Appeal’s consent - but it is not a right of presence. Thus a right to attend in person could not given within the terms of the Draft Order since the right to attend does not exist in underpinning appeal law in the first place. The intention therefore is to preserve the distinction between cases where an appellant is entitled to be present and those where he may attend only with leave.

144. The NIO added that the Court already has an overriding obligation to ensure that an appellant receives a fair hearing in accordance with Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights and it was anticipated that the Court of Appeal would always exercise the power in accordance with the interests of justice and the appellant’s right to a fair hearing.

145. Having considered the evidence provided and the further clarification on the proposals and concerns received from the NIO, the Committee supported the live link provisions, but considered that the consent of the offender to a live link direction (as provided in Article 80 on sentencing) should be extended to live links in appeals. Members also considered that further thought should be given to the provisions in respect of vulnerable accused persons under 18 and the specific concerns raised by NIHRC.

Recommendation

146. The Committee recommends that the consent of the offender provision should be extended to any live link direction given in the Court of Appeal.

Recommendation

147. The Committee recommends that the NIO should give further consideration to the operational aspects of the provisions relating to vulnerable accused persons under 18, taking account of the concerns raised by NIHRC, to ensure that the live link procedures do not present any additional barriers to young persons’ needs.

Legal Aid (Articles 83 and 84)

148. The Committee supported the proposal to extend legal aid provisions to anti-social behaviour orders.

Changes to the Police and Criminal Evidence (NI) Order 1989 (Articles 85 to 88)

149. The Committee supported the proposed changes to the police and criminal evidence legislation which:

- provide additional powers of entry for the police to effect an arrest for offences of: common assault; riotous behaviour; harassment; and contravention of a non-molestation order;

- allow the police to attach conditions to bail before charge etc;

- allow changes to police authorisation levels in relation to x-rays in drugs cases or to the investigation of offences or the treatment of persons in police custody.

Penalties (Article 89)

150. The Committee welcomed the doubling of sentences for knife and weapon crimes but it was felt that increasing sentences alone would not be a successful deterrent. There is a view that some young people carry weapons in case they themselves are attacked and that they will make a judgement call on whether the chances of being caught outweigh the chances of being attacked and injured themselves.

151. Members thought that there was a further opportunity now that the law is being changed to send out a really strong message to our young people that they should think seriously about the consequences of carrying weapons because, if caught, the courts would deal with them severely. The Committee considered that this issue could be covered in any media campaign flowing from of the Committee’s recommendation on publicity (see later section on publicity).

Driving Disqualification for any Offence (Article 90)

152. The Committee supported this proposal which provides courts with the power to disqualify an offender from driving on conviction of any offence – not only a motoring offence. Disqualification can be in addition to or instead of any disposal which the court might choose to impose.

Proving Execution of Arrest Warrants (Article 91)

153. These proposals would enable a wider range of magistrates’ courts to hear the proving of the execution of arrest warrants. The powers would enable the execution of those warrants issued by a lay magistrate or resident magistrate or a magistrates’ court in one County Court Division to be proven in a magistrates’ court in the County Court Division of arrest or in a magistrates’ court in a Division adjoining the County Court Division of arrest. The Committee supported these provisions.

Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (Articles 92 to 93)

154. The proposal to allow applications for interim ASBOs to be possible without notice being given to the defendant was opposed by NIHRC. Its representatives said that the proposal merely served to exacerbate the Commission’s existing concerns regarding the granting of ASBOs. The NIHRC acknowledged the existence of precedents for ex parte proceedings in a range of areas of law but indicated that ASBOs were different because ASBO proceedings blurred the division between civil and criminal law.

155. NIHRC was concerned that the odds are very heavily stacked against the person against whom the order is sought, with hearsay evidence being admissible and the normal criminal standard of proof not being applied; and that without an opportunity to present arguments at an interim hearing the likelihood of an inappropriate ASBO being granted would be greatly increased. NIHRC commented that the NIO had proceeded with this proposed extension without any cogent policy rationale or statistical basis. NIHRC also cited a judicial review decision in 2005 in which the issue of the power of a Magistrate to grant an interim ASBO without notice was considered - a resident magistrate’s refusal to grant such an order without notice in the absence of a specific legislative power was upheld.

156. The Committee heard that the NIO and Criminal Justice Inspection had jointly commissioned an evaluation of ASBOs and that the report would be published in the next few months. NIHRC said that seeking to introduce this extension to ASBO powers in advance of the publication of that evaluation would be premature.